Abstract

How might we create a world empowered by music? How might we change our culture to accept music as an innate intelligence and assist others in discovering the joy, enchantment, mystery, and power of music in their daily lives? Answers to these questions might be found in redefining the content and pedagogy of music appreciation or music courses offered to non-majors in higher education by including elements discovered through music and pedagogical research along with active learning. This article includes an overview of the course, “Exploring the Power of Music,” a general music course that encourages students to explore the personal relevance, meaning, and value of music in a broad range of disciplines and schools of thought. This teaching model moves music from a spectator sport to an active learning experience. The class is framed by a model blending science with human collective experience and personal inquiry, allowing students to explore the powerful forces of music’s influence on humanity along with their own intimate relationship with the art and science of the discipline.

Is music encoded into our DNA? Has it been the cornerstone of our evolution or part of the building blocks of life itself? What is its value to humanity? We may not have definitive answers to these questions, but we do have numerous evidence to suggest that music has special powers. For example, the idea that life itself is music, sound, and song comes to us through various sources, including Jazrat Inayat Khan’s writings which explore ideas from the ancient world such as those by the Persian poet and sufi mystic, Hafiz: “Many say that life entered the human body by the help of music, but the truth is that life itself is music."1 Present day researchers, such as archeologist Steven J. Mithen, give us more to ponder on the subject through the voice of Western science. He posits that a tonal communication system utilizing melody and rhythm, primary components of music, was used by early primates before the development of language and that his conclusion “is the same as John Blacking’s in How Musical is Man?: ‘It seems to be that what is ultimately of most importance in music can’t be learned like other cultural skills: it is there in the body, waiting to be brought out and developed, like the basic principles of language formation.’” 2 Researchers continue to confirm and deepen knowledge held by centuries of the collective and personal experiences of many cultures and individuals who have used music to communicate, to heal their physical, emotional, and spiritual lives, and to influence and understand the world around them. But, are music educators utilizing this information in their classrooms? How are they using music to empower the world and to create advocates for the importance of music in our lives and in our educational systems?

Even with all the copious evidence regarding the powerful aspects of music, it is still often viewed as merely entertainment and music education is not widely valued. Music educators continue to feel a need to write justifications for teaching the discipline, with monographs and journal issues dedicated to the topic.3 Deep lines continue to be drawn between practitioners and spectators of music. This divide is often nurtured in our music classrooms, especially in higher education, causing practitioners to feel the undue pressure of perfection and spectators to feel unwilling or unworthy to make their own music. Courses that are taught under the umbrella of music appreciation or taught to non-music majors tend to foster this divide in their lack of active learning components. While the benefits of active learning are well established, it is rarely included in music classes beyond K-12. Even though music is a natural active learning partner and has been widely used to teach other concepts in non-music classrooms, the focus of non-major music courses in higher education is still predominantly the historical survey. Nicholas J. Enz’s review of the literature, “Teaching Music to the Non-Major,” notes that the focus in these courses is mainly on teaching listening skills.4

While listening to the various canons is important and can be engaging to some students, the piece that is consistently missing in addition to active learning is attention to personal relevance. Along these lines, one of my students made astute observations while pondering the question of whether they were a musician: “I wasn’t sure if I could fit into this cool club of ‘musicians’ since I technically didn’t play an instrument. But I now realize that someone who plays an instrument can be a non-musician inside. … A musician is someone who may not fully understand music, but someone who deeply listens to, thoroughly appreciates, and loves to explore it regardless.”5

In his 1998 landmark work, Musicking: the Meanings of Performing and Listening, Christopher Small challenged us to consider the idea of musicking, moving music from a product to a social process.6 In a published lecture on his ideas, he asserts that:

… the meaning of musicking lies in the relationships that are established between the participants and the performance. Musicking is part of that iconic, gestural process of giving and receiving information about relationships which unite the living world. … Musicking is thus as central in importance to our humanness as is taking part in speech acts, and all normally endowed human beings are born capable of taking part in it, not just in understanding the gestures but of making it their own.7

Adding all the various aspects of musicking to the classroom, including active listening, performance, and creation of music, along with providing opportunities for students to explore music both in the social context of the class and in various contexts outside of class allows them to develop both personal and collective relationships with the discipline.

Extending these ideas even further, we might ask ourselves how we might bring about a world empowered by music. How might we change our culture to accept music as an innate intelligence and assist others in discovering the joy, mystery, and power of music in their daily lives as well as utilizing the language of music to teach important life skills? In Seeking the Significance of Music Education, Bennett Reimer suggests that “every subject worthy of study, including music, embodies a diversity of values, all deserving our attention. Some of the values warrant our deepest devotion. One task of a philosophy of music education is to illuminate what those might be, so that in pursuing them, our effects on our students can be as beneficial as music is capable of making them.”8

Seeking to impart potential human musical capacities and benefits in my own teaching led me to ponder how we might use music education in new ways to not only develop skilled technicians, but to encourage the innate musicking abilities in all of us as well as to create support for the discipline. Is it possible that shifting our way of teaching music, especially music courses to non-majors in higher education, might inform or contribute something greater to humanity? As I noted in an earlier publication, “If we nurtured the idea that there is enough for all and valued each individual’s unique musical gifts, we might be able to sing and play creative solutions to our problems and have lives filled with healing music.”9 Music has so many powerful aspects that we might also be able to use it to teach the art of interconnection, communication, and transformation, and foster the evolution of human thinking and action.

I have been exploring new ways to incorporate elements of the breadth of research and historical information on music into innovative courses at the university level. I also utilize supportive ideas from the scholarship of teaching and learning along with my own unique training and viewpoints from neurolinguistic programming, information literacy, and social artistry to reimagine how to teach music appreciation.10 These approaches allow students to explore the powerful personal relevance, meaning, and value of music within a broad range of disciplines and life circumstances. The courses are framed by a model blending science with human collective experience and personal inquiry.11 Incorporating these ideas provides the hook, the catalyst that elicits the defining moment when a student becomes infused with an insatiable appetite for inquiry and learning. It also helps foster various kinds of thinking; not only critical thinking, but also creative, global, and contemplative thinking. At the same time, I use strategic pedagogy to evaluate the results.

In 2011, I had an opportunity to further develop these ideas into a course for the interdisciplinary Honors Program at my university I call “Exploring the Power of Music.” The course originally was a three-credit writing-intensive seminar which I have since expanded to five credits. The result is a model that moves music education from a spectator sport to an active learning experience in which students are led through a variety of musical explorations, are encouraged to find personal relevance and life applications, and gain lifelong learning skills through utilizing the language of music.

Pedagogical Framework and Philosophies

The goal of the course is to give students enough inspiration to ignite a spark for musical inquiry and also to meet each student wherever they are in their understanding. This means that the course needs to be infused with a variety of elements that support personal relevance within the course structure.12 Being open to the direction of each student’s development means acting as a facilitator who supports the learning process. In their Facilitating Reflective Learning in Higher Education, Anne Brockbank and Ian McGillir describe how taking on such a role might change our teaching focus:

Working as a facilitator is more risky and vulnerable than teaching through a didactic format. … In engaging in this way we are doing no more than we are asking of the learners who come into higher education. This is not to suggest that facilitation implies a flabby, self-indulgent and unstructured approach to working with students. Facilitators have a distinct and rigorous role in taking responsibility for creating the conditions conducive to reflective learning.13

While this is a challenging way to teach, the rewards are great.

Facilitation

My version of a facilitated learning environment includes creating a basic course structure with broad topics chosen from the various ways music is powerful to humanity (See Appendix A for a sample course outline). I then gather a core group of possible readings, exercises, assignments, and activities to which I am constantly adding, and I remain open to changing the details and direction of the course as the learning process unfolds. I pay attention to the questions, learning needs, and desires of the students along with the particular learning personality that emerges in each group of students. I allow students to become active participants in the learning process. For example, one year the students wanted to share with each other the ideas they were discovering from their optional activities, including experiments they were designing for themselves as they explored these ideas. In response, I made time so that students could present short reports and responses in class. Another year, the group was not willing to share in this way, but was interested in having voice lessons since they were singing so I instituted a series of voice lessons, which corresponded to the ideas being exploring in class. Since a core element of the course is student research and presentation, I also change my mini-lectures, exercises, or readings for class at times so my contributions will not duplicate what students are contributing.

Teaching-learning Community, Building in the Social Process

As a part of strengthening the facilitation process, the class operates as a teaching-learning community. This requires students to take responsibility for their own learning and encourages them to share their thoughts, questions, and newly gained knowledge with each other. They are urged to keep an open mind when they are not inspired by a reading or an exercise, and to pay attention to how others in the class and the class as a whole are experiencing the materials. Students often learn the most by observing the perspectives of their fellow students. This kind of teaching means that I need to enrich my own explorations by reading broadly within the literature of music and learning, to search for inspiring material and pedagogical ideas, and to remain flexible. By observing, I can respond to student questions, reflections, and interests by changing materials, exercises, and the like to provide challenges in directions they find most intriguing.

Reflective Learning

Assignments are based heavily upon reflective writing and are intended to encourage students to include the questions that arise along their journey. As Tobin Hart has found in his work on contemplative learning, “simply asking for the questions that the student would ask about the topic, what they are curious about, and what they really want to know but have been afraid to ask serves as another means to loosen the lock of predetermined answers on the process of knowing.”14 Reflections are written on three levels: journaling allows students to capture their experiences and thoughts that are private, just between themselves and the page; formal assigned reflections are turned in to the instructor; and another group of reflections are shared publicly with the entire class.15 Brockbank and McGill also discovered that, “by consciously engaging in reflective practice, the learner has created and in turn creates the conditions for the type of learning that is the essence of higher education.”16

Contemplative elements are also included for in-class activities. For example, students have class time to write about their experiences after an in-class activity. These reflections and experiential pieces assist with the development not only of critical, but also creative and global thinking. Hart also concludes, “the natural capacity for contemplation balances and enriches the analytic. It has the potential to enhance performance, character, and depth of the student’s experience.”17

Exploration, the Paths of Inquiry

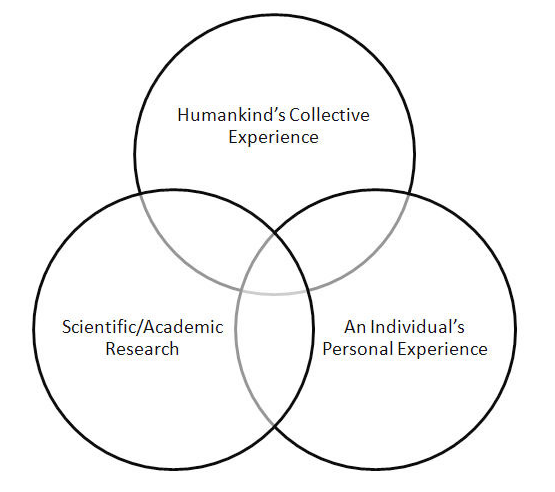

I ask students to be open to the science, the mystery, and everything in between with regard to our musical explorations. Elements from the viewpoints of history, sociology, psychology, neuroscience, anthropology, and other disciplines are introduced along with a substantial amount of music making. To help facilitate a broader view of human musical knowledge and thinking, I frame course content and structure upon my model, The Three Realms of Knowing (see Appendix B). This framework helps students understand the context of the materials presented, assists in facilitating discussion, and can aid them in framing their own research.

Many optional paths of exploration are provided during the course so that students may spend additional time and effort on the topics that intrigue them most. These include extra readings, videos, and exercises they can pursue on their own to further their understanding of each topic. I use a grading system based upon one developed by Dr. Dick Dalton, Associate Professor of Health and Wellness at Lincoln University of Missouri. He offers his students “smorgaspoints” to facilitate optional pathways students can take in his classes (see Appendix C for a sample grading system). It is a rare student who does not find something of personal interest to explore more deeply. These optional explorations sometimes lead students to topics for their term-long research assignments. Connections to other opportunities from within the University and student-proposed exercises are also included as optional assignments. For example, students can write the required essay for application to the Library Research Awards or write their final reflections for their Honors portfolio.18

Variations on a Theme

I introduce many subthemes in the course to give the students as many opportunities as possible to engage with the materials as well as integrating elements from my own background and expertise. I find that the students respond much better to any portions of the course in which I engage with my own personal experiences, strengths, or philosophical ideas as this encourages them to search for and share their own. I would urge anyone who wants to teach such a course to use the basic topics and general framework and include their own personal experiences and strengths into facilitating the learning process.

I have taught this course as a one credit freshman seminar as well as both a three and five credit graded course to fifteen to twenty students. I have also thought about ways to extend the course to larger groups of students and believe the ideas would scale. One might use traditional quiz sections as small group active learning sections along with including more active learning elements when the entire class is together. Small groups could contribute their findings to the larger group, including small group profiles, which could be used, for example, to further their exploration of the collective knowing of the class as a whole. Allowing students to participate in the information gathering and learning process seems possible in these contexts and may enhance student understanding and engagement.

Course Content

The class takes a whirlwind tour of the various historic, interdisciplinary, and multicultural viewpoints of music as it experiments with the various ideas both in and outside of class. I use a basic outline for the course (see Appendix A for a course outline with sample activities and assignments), but as part of the learning facilitation process, topics are deleted or modified depending upon questions that arise during the course and the topics students choose for their research projects; this approach allows us to cover as much material as possible and it permits students to fully participate as experts in the teaching and learning community.

Early in the course I assign a reading on creative thinking written by Robert and Michèle Root-Bernstein. They introduce the idea that many great thinkers utilize intuitive and creative thinking as a part of their process much like a master chef. They assert, “it is imperative that we learn to use the feelings, emotions, and intuitions that are the bases of the creative imagination. That is the point of gourmet thinkers and education.”19 The creative elements of music making lend themselves perfectly to developing these skills. Most of the students in the class are science majors, so we talk about the number of medical doctors and scientists who are also musicians, and discuss how studying a creative art like music might enhance our thinking in general. As one of my students wrote, “We must continue education in the arts. I believe the process of creativity is not unique to a particular subject, all subjects must use it, and the process is similar across fields. Giving people the chance to do other creative things can lead to people learning how to apply it to other subjects.”

As an introduction to music’s power, the class examines why humans might be musical, explores the theory and physics of sound, experiments with modes, scales, and ragas, and takes a trip to a stairwell with a ten-second reverb, where students play with various sounds. 20 Students are asked to watch the PBS video, “The Music Instinct,” along with perusing the latest research topics from recent International Conference on Music Cognition and Perception proceedings to get a broad overview of the current musical science. 21

Throughout the term students ponder their own definition of music and their identity as a musician. They also explore how references to music are embedded into our language, for example, in the expression “that’s music to my ears.” Each class begins with “music about music” pieces which reflect the ideas of the power of music in the music itself. For example, I use Henry Purcell’s “Music for a While” to contemplate what the class will be doing in our ten-week journey. Examples for this segment are chosen from a variety of musical genres and cultures; some are recorded, some are sung in class.

Other activities have students ponder their listening habits and explore how listening to music affects each person, including some experimentation with pieces that are composed for the purpose of changing consciousness.22 The class also explores ideas about “Deep” listening, utilizing the work of Pauline Oliveros, Evelyn Glennie, Judith O. Becker, and others.23 The class examines music from various cultures, the use of music for healing from shamans to Western neurological applications, music and learning, how music can be used for service, and how it can change brains and entrain us. The course covers the differences in the brains of musicians and non-musicians, looks at how artistry might be used to take world leadership to new healthy levels, and gives students the opportunity to engage in musical activities in every session.24

Guest experts visit class to provide active learning experiences and to deepen students’ understanding of specific topics. These experts are asked to share personal stories of the power of music in their own lives and in the lives of their students, patients, and the like. Students especially enjoy these sessions and gain new understanding by interacting and making music with dynamic practitioners who have nurtured their own musical lives and careers.25

Each quarter ends with a celebration of music – usually a performance art piece written by the instructor in the last two weeks while the students are presenting their own research. The work uses a variety of media to summarize what was covered in the course and draws upon the students’ talents, including a final session of making music together. One of the pieces was framed around a poem by William Ayot called “Anyone Can Sing!” which is something the class came to believe during the course of the term.26

I leave the students with two questions to ponder as they leave on the last day: First, what makes your heart sing? The students are given time to write or draw their answers to this question during the performance. The second question asks whether music can be an answer to any of humanity’s issues and questions. As one of my students reflected, “Music has power so strong it can carry and lift the whole world’s weight.” We often end with a song by Chloe Goodchild called, “The Singing Field,” which uses her musical modification of the famous Rumi quote, “Out beyond ideas of right and wrong doing, there is a field, a singing field, I’ll meet you there.”27

Active Learning – Providing a Variety of Musical and Contemplative Experiences

Active learning elements are incorporated throughout the course. These include guided imagery; exercises to promote active and deep listening; various forms of reflective writing; communal and individual singing, playing, and composing; interactions with guest experts; and field trips. I encourage students to suggest class activities for extra credit, and each quarter their ideas are incorporated into the course.

This interactive environment bonds students in a way I have not seen before in the classroom. Several students have asked to have reunions and others have made observations about these bonds in their reflections. Was this because the active learning environment encouraged students to participate, or did the very nature of the connections music brings to humanity play an important role? One student was convinced that the power of music was the catalyst:

I distinctly remember at the start of the quarter how shy and reluctant we were to sing, dance, or hum as a group. However, the activities were engaging and interesting enough to take us away from the social discomfort and into the music. As we were drawing our heart songs … at the end of the quarter, I could feel the camaraderie that had been formed. The music was the catalyst that drove the coming together.

Some even felt the group dynamic was one of the most important elements of the course: “I have really enjoyed taking The Power of Music this quarter … but more importantly we’ve been able to ponder as a group what speaks to us.” Mary Ellen Junda found a similar phenomenon in her “Sing and Shout” course, where “communal singing provided a means to … develop a sense of community with peers and to experience firsthand the feelings of inspiration, kinship, and joy—to be emotionally transformed—when voices were joined together in song. By inviting participation right from the start, the class immediately became lively and interactive.”28

Assignments

Students are assigned two to three resources with which to interact and reflect prior to each class session. These usually represent a perspective from at least two realms of knowing. For example, they might be assigned to read an academic article and watch a video aimed at the public at large, or read one quantitative study from neuroscience and one qualitative study from sociology. A set of questions helps guide the reflective process. The personal realm of knowing is covered in weekly explorations relating to the previous class sessions. Students are asked to try these exercises throughout the week, write a reflection on their experiences, and post them on the course online board. In addition, they write a short paper on their “Personal Music History” in which they are asked to contemplate how music is related to their lives, including their family, culture, and the like. This assignment gets them started on acquiring research skills along with providing an element of personal relevance to the course (see Appendix D for sample writing assignments).

Group projects help students bond and extend the range of topics that can be covered in ten weeks. Groups are assigned broad disciplinary areas—defined by the University’s list of majors—and are asked to explore some of the ways music overlaps with their assigned disciplines. They share their findings during in-class presentations. Each group also analyzes a set of student posts from the weekly exercises. They are asked to summarize the reflections, looking for similarities or differences, and to compare the class’s experiences with those of the broader collective or scientific knowledge they have discovered.

Each student picks one of their burning questions and uses it to explore their own personal path of inquiry throughout the quarter, supported by scaffolded assignments. Each student’s inquiry leads to a final annotated bibliography and in-class presentation on the expertise they have gained. By the final presentations the students all find something they want to share, and they are interested and attentive to their colleagues.

On the first day of class, I ask students if they think music is powerful and to elaborate by writing for five to ten minutes in class. I give these back in week nine in preparation for their final assignment. They use these initial reflections along with their journal entries, written reflections, and other assignments to write a reflection on how they use the power of music in their lives, how their views on the topic have broadened or changed, any special "aha" moment, and any intentions they have to incorporate music's power continuously in their lives.

Evaluations/Assessments

I place assignments and reflections strategically throughout the course to assess how students are absorbing the material and what questions are arising. Gaps in understanding can immediately be addressed and new paths of learning can be spontaneously facilitated. Each student is inspired by a different set of experiences. It is rewarding to watch each of these individual lights shine with their own excitement and understanding for the discipline.29

Outcomes and Observations

Students came away with a deeper understanding of the power of music in their individual and collective lives and acquired tools to assist with their ongoing explorations. They reframed the way they look at a world full of musical meaning. Music helped them get a sense of “otherness” and helped them to notice and share experiences among various groups. It opened their minds to new pathways while accompanying them on their psychological, social, physical, and spiritual journeys. Students had major “aha” moments, healings, understandings, and were in awe. Some who did not consider themselves musicians on day one changed their minds and found new excitement for renewing their commitment to musical activities, ranging from humming their day to singing in the shower to composing and even to cutting a new album.

Students’ personal explorations spanned a broad range of topics. Some explored music of specific cultures, including cultures with no term for music. Others looked at its influence on social movements like Afro-solidarity, or how specific genres are linked to various groups, for example, how electronic music is linked to the civil rights movement and gay communities. Many chose the healing power of music and researched its application to specific diseases or healing modalities. Several researched music’s influence on the emotions, including film music. Other explorations spanned topics such as sound in the womb, synesthesia, zoomusicology, biomusic, a grammar for music, and topics related to mathematics, engineering, and business. Students especially valued the flexibility to pursue their own interests and learn from their fellow students.

Reading the students’ inspiring final reflections was rewarding and solidified my belief that the purpose and outcomes of the course were being met. They all found a deeper personal relationship with music, many were surprised by the depth and breadth of music’s influence and value, they all believed they were natural musicians in some way, and they went away with a renewed energy for including music in their lives. I believe the effect of the learning was beneficial, valued each individual’s unique gifts, and won many supporters for the inclusion of music in our educational systems.

While I am excited by what I observed in my students’ learning, the outcomes are best described in their own words. Below are samples of six of the student's reflections:

It’s been an immersive experience, from singing traditional music with your peers in class to looking at the latest research on music and how it affects us and is completely interdisciplinary. I have immensely enjoyed being a part of this focused academic setting and the small, passionate community it provided ….

Taking this class has broadened my views of music, what it means, how it’s made, and its effects in ways that I did not anticipate it to … it has reframed how I approach music and has given me a chance for introspection on how music affects me, society, and the world.

Throughout the last several weeks, I learned that the power of music extends far beyond the scope of my understanding. Music can create friendships and truce where previously there was anger, misunderstanding, and distrust. Music gives people a sense of unity and oneness. Music can cross cultural and racial boundaries. … Music is capable of starting movements, soothing nerves, and relieving pain. … I leave this class wondering if music’s power comes from some sort of spiritual awakening, allowing humans to transcend what we believe ourselves capable of, if even for the shortest period of time.

After taking this class, I have realized that I had only scratched the surface of what is possible with music. … I realized that music has a deeper connection to humanity (and potentially all life) than I previously realized. … I have slowly started to weave different tidbits of information from this class into my daily life. … I plan on integrating much of the music education from this course into my long term future.

Songs and music are powerful things that change how we feel. It really is like someone injects into you happiness, sadness, or some kind of bottled emotion. … Even in 10 weeks I learned much more than I thought I possibly could about music.

At first I only saw music as an art that could supplementally be very useful to society. Now I see that music is more than just a supplement; it’s incredibly powerful and alone it can change lives and cross borders in ways few other things can.

Many students became more reflective and self-observant in general. One student put it succinctly: “I can honestly say that taking this class was always the highlight of my week … as I look back at this class, I can’t help but think about how much I’ve grown personally, academically, and musically.” Another said, “Lastly and perhaps most valuably, I gained a new sense of self-confidence in this class.”

While I am in awe of how taking the course affected students’ sense of themselves, the most rewarding aspect was their new enthusiasm for becoming musical participants, beyond being engrossed in their iPods. As one student noted:

There are a couple of major takeaways that everyone should be aware of whether you took this class or not. The first is that our Western world doesn’t sing enough. … We like to think that the only correct way to sing is with a scrubbed audio and all imperfections removed. I will say that singing can and should be done by everyone regardless of what you think of your voice. The second is that you have the power to find and play the music that is powerful for you. … Don’t be afraid of what makes you move, sway, and bob your head.

Students who formally study music often come away with a healthier relationship with their art, regaining enthusiasm they had lost along the way. One student’s reflections clearly showed this change:

I put so much of myself into self-abuse over how imperfect my music is. It is just not good enough—not good enough for my professor, and not as good as my peers. I think this class is exactly what I needed to realize that if this is the way I am trying to succeed in music, I am doing it wrong. A lot of music is about the pursuit of perfection, this is true. But the reality is that perfection doesn’t exist, and if I spend all of my time chasing an impossible ghost, I will lose sight of the point of music in the first place. That point being to reach people. To, just for a moment, show someone an emotional piece of yourself that may otherwise never get out. It is to change people, to make people get up and dance, or bring them to their knees in sorrow. It is to help us deal with the fact that we exist in this universe, and we will never know why … to use our gifts in a very noble way—to help people and to spread art, tolerance, and love throughout the world, one person at a time.

I, too, learned a great deal from my experiences in this course. My students’ reflections not only assisted me in the process of facilitating learning, but also provided me with a privileged glimpse into the thoughts and developing minds of our future. In addition to newfound connections to music, students often expressed their puzzlement at the lack of support for music in the schools. The message I heard many times in their reflections and in class was that everyone should know about these powerful aspects of music and that music should be a requirement in the schools. These experiences show that this new way of teaching and learning, this new way of defining music appreciation, can truly make a difference in how we experience, teach, and value the power of music.

APPENDIX A

Sample Course Outline with Examples of Activities and Assignments

The class meets two times per week for ten weeks for one hour and fifty minutes. Class sessions consist of a variety of mini-lectures, discussion, student reports, and a variety of activities. This is a partial list of readings and activities used for the course and does not include any optional materials.

Weekly Explorations: Students are asked to write their observations and reflections on the post board after each week-long exploration. They are encouraged to include examples of music that illustrate their ideas.

(Week 1) Setting the Scene: What is music? Why are we musical? What is Your Personal Music History?

Students begin the course by completing an information sheet (e.g., Do you consider yourself a musician? Do you sing or play an instrument? etc.). I compile this information and share a class profile on day two. They also complete an in-class writing assignment giving their initial thoughts about the power of music and are given their “Personal Music History” assignment. The first session introduces students to a variety of definitions of music along with models of how music intersects with the world, for example, the “Functions of Music Within Society” chart from Barrett’s Sound Ways of Knowing. The class discusses readings on the origins of music, why humans are musical, and why we might want to study music; for example, Hodges and Sebald’s, “How We Came to Be Musical,” from Music in the Human Experience.

Example activities: Sing a welcome song from West Africa; musical introductions—each student intones their name followed by the group chanting their name back to them in circle; dancing an ancient Templar dance to Enas Mythos; internal and external listening exercises.

Weekly exploration: Post your favorite piece of music or an example from your favorite genre of music.

(Week 2) Listening, Perception, Entrainment, and Group Formations

Students discuss why studying music might be beneficial and experiment with more listening ideas, are introduced to entrainment, share their personal music histories with each other, and work in groups on an assignment that explores how music is integrated throughout assigned disciplines.

Example Assignments: Read “Rethinking Thinking” and Copland’s “How We Listen;” watch Evelyn Glennie’s “How to Truly Listen.”

Activities: More listening exercises; entrainment videos; heart pulse exercises from Kay Gardner’s Sounding the Inner Landscape; perform piece from Pauline Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations.

Weekly Exploration: Post a piece of music that relates to your Personal Music History and write about how it relates.

(Week 3) Discovering Your Path of Inquiry and Playing with Sound

Students spend time in the research lab working on their group projects and searching for topics for their term project. We have a guest who explores sound production and helps students experiment with sound in a stairwell with a ten second reverb.

Example Assignments: Read Hodges, “Acoustical Foundations of Music,” from Music in the Human Experience; watch Nina C. Ramsbottom’s “Landfill Harmonic;” begin term project.

Weekly Exploration: Pay attention to how the music around you is entraining you, how it makes you want to move, reminds you of something, and so forth. Include a piece of music that makes you want to move. Note: I analyze the pieces the students post, for example, are there similarities or differences in tempo, genre, or other elements, and present the results in class.

(Week 4) More Sound Exploration and The Power of Music Across the Disciplines

The class continues to explore how sound became musical genres and spread to different cultures, including exploration of temperaments, scales, ragas, and the like. Students present their group projects on how music integrates into their various assigned disciplines.

Weekly Exploration: Start listening to the sounds in your environment, including those you consider music. Answer the questions, “What is music to my ears?” or “What do I consider music?” (I encourage students to use resources handed out in class including listening questions by Pauline Oliveros and my own “Listening on the Four Levels of Awareness.”30)

(Week 5) The Power of Musicking

The class explores how music changes brains and affects musicians. A guest singer-songwriter in the blues tradition who worked playing music in psychiatric facilities joins us for a session on his work and does improvisational exercises with the students.

Example Assignments: Read Wan and Schlaug’s “Brain Plasticity Induced by Musical Training” and Skoe and Kraus’s “A Little Goes a Long Way: How the Adult Brain is Shaped by Musical Training in Childhood.”

Activities: Soundpainting session

Weekly Exploration: Students are given one of two exercises: (1) Pick a chant or mantra that is meaningful to you. Start each day with intoning the mantra; (2) Start each day with humming. Try to feel it deep in your body. For both: Continue the chant/humming throughout your day when you have down time.

(Week 6) The Power of Music to Evoke the Emotions and Enhance Our Learning

The class explores how music affects human emotions and how it might enhance learning along with looking at both sides of the “Mozart Effect” debate.

Example Assignments: Read Tan, Pfordresher, and Harre’s “The Emotional Power of Music,” from Psychology of Music: From Sound to Significance, and Hallam and MacDonald’s “The Effects of Music in Community and Educational Settings,” and peruse Gabrielsson and Bradbury’s Strong Experiences with Music.

Activities: Exercises using clickers exploring both how music reflects and induces emotions. Weekly Exploration: Listen to a variety of music unfamiliar to you and try one day without any music. Also explore the idea of labeling how specific music affects you so you might be able to utilize the pieces for specific purposes in the future. For example, if a piece makes you feel happy, you might label it “happy music.”

(Week 7) The Power of Music to Heal

The class explores the use of music in healing both from shamanistic/historical/cultural perspectives as well as what science is learning about the powers of music to heal. A certified music therapist visits the class and talks about the profession and the research in the field.

Example Assignment: Read and listen to examples in Pat Moffitt Cook’s “Shaman, Jhankri & Nele,” and explore the American Music Therapy Association’s website, including reading materials about specific populations in the fact sheets.

Weekly Exploration: Experiment with a variety of music and silence and notice how it affects your studying.

(Week 8) The Power of Music to Serve and Connect

Students explore various ways music connects humans in various contexts as well as how music is used for service. A guest music educator/sociologist shares how musical elements are connected between cultures and how immersing oneself in another’s music can help one understand them more clearly.

Example Assignments: Watch Connor, Payton, and Caldwell’s “Music for the Soul, Healing for the Brain,” and explore some of the music service projects listed in the course research guide.

Weekly Exploration: Listen to the music in your environment. Notice how music is being used by and affects others and yourself, how musical metaphors appear in our language, and how it functions within a social context.

(Week 9 & 10) Sharing Our Expertise; Wrap-up and Musical Celebration

During the last two weeks students present their research in class. The course ends with a celebration of music, usually a performance art piece to be performed by the whole class, written by the instructor.

APPENDIX B

Using the Realms of Knowing in the Classroom

Figure 1. Three realms of knowing.

Further Divisions of Each Realm

While one might search for the collective knowing or understanding on any subject by any individual (personal realm), humanity as a whole (collective realm), or the scientific/academic realm, each realm can be further divided into various groupings. For example, within the collective realm, there are groups who have their own understanding which may overlap or differ from other groups, but often have some common ground. One can also focus on the various intersections between the realms, for example, what has science discovered that humans as a whole have collectively believed or known for centuries?

Examples

Personal Realm: As a pedagogical tool, this realm provides one way to structure personal relevance into learning. What is your personal experience with this exercise/reading/topic, etc.? What are the questions that are arising for you? How can you bring your personal experience into the conversation regarding this topic? How does this apply to you personally?

Collective Realm: How is this topic viewed by various groups (e.g., social, political, religious, ethnic, or cultural)? Has it changed over time (i.e., during different historical periods)? Do we see similarities or patterns of collective understanding?

Scientific/Academic Realm: Is this topic viewed differently between disciplines or by type of research/researchers (e.g., quantitative vs. qualitative exploration)? Are there similarities in research in different disciplines or are there interdisciplinary elements being utilized? Would collaboration between disciplines make this stronger?

Intersections Between Realms: Where does the experience of researchers, humans in general, and your own understanding overlap? Where does it differ?

Example Applications

Supporting Critical, Creative, and Global Thinking as well as Encouraging Interdisciplinarity: Note that the information and perspectives of these realms can change over time; for example, an individual has the opportunity to continually add to their own personal knowing as well as understanding more about other realms. In turn, the viewpoints from other realms can also change due to new discoveries, understanding, and cross pollination.

Understanding the “Other”: Whose voice am I hearing? Within and between each realm there are similarities and differences. How do these relate? How do they influence my thinking or the ideas and thinking of a specific group or realm? How do they influence those outside the realm or group?

Discussions: Whose voice am I hearing? Is this only my opinion or is my viewpoint based upon or related to other realms of knowing? Do I have sufficient perspective to argue a point or do I need to inquire into other realms of knowing before I can firmly understand the topic? What perspective is missing? From which realm are others speaking?

Research: Whose voice am I hearing? What realm is represented in the article, book, presentation, web blog, and so forth, I am reading or watching? What realm am I attempting to study? How do the different realms relate? How do they differ? How are they similar?

APPENDIX C

Grading Policy

Below is a list of points for assignments (these can change slightly as the quarter progresses, depending upon what is happening in class). Final grades for the course are calculated by converting the number of points to the percentage of total possible points and converting percentages to grade points using the UW Grading System (e.g., 90% of the total points will be a 3.5).

In addition to required assignments, there will be optional "smorgaspoint" opportunities throughout the quarter. You can use these "smorgasopportunities" to more deeply explore a topic you find especially interesting or to raise your grade. They will not substitute for the total points lost to any major assignment (e.g., you must participate in a group project, term project, etc.). Let’s dig in and have fun learning!

Points

Weekly Participation and Preparation (5 points each; 20 sessions; 100 points possible)

Weekly Listening Go-Posts and reflective papers: ca. 22-25 (3 points each; approximately 66-75 points)

Short papers (30 points): (a) Personal Music History (10); (b) Final Reflections (20)

Group Projects (30 points): (a) Disciplinary presentations (20); (b) Go-Post Analysis (10)

Term Project (75 points)

Total Points: 301-310 (possible)

Extra “Smorgaspoints”/optional exercises/assignments (there may be other opportunities that arise as the quarter progresses) are worth 3 points each unless otherwise noted.

1. Latest music perception/cognition reflections (6 points maximum)

2. Reflections on optional readings/listening/exercises

3. Three roles exercise reflection sheet (Group exercise) = 5 points

4. Written reflections on the chant or humming exploration you did not do for class

5. Concert experience reflection sheet (6 points maximum)

6. Extra points possible on final project rubric

7. Propose an extra credit project/exercise to instructor = variable

APPENDIX D

Sample Writing Assignments

1. Personal Music History Assignment

Explore at least one personal connection you have to music in your “genes” or in your family. Examples can be music your mother played to you while you were young, any aspect of music associated with your family, or something related to the music in your ethnic group or culture with which you identify. Use resources from the class research guide to find articles and information about your topic along with your own memories and personal interviews of others.

Write 1-2 double spaced pages on this music and how it influences you personally. Possible questions to answer include: What is the background/history of this music in general? How does it relate to you personally? What about it helps define, empower, and/or influence you? Be sure to properly cite any resources you quote or paraphrase, including interviews.

2. Term-long Project Description

The class will be exploring a variety of topics related to the power of music and its influence upon humanity and the world. Along with the exploration we will do in class, you will spend the quarter exploring a topic of personal interest that relates to the course. These can be deeper explorations of a topic or assignment presented in class, center around a specific genre of music, or explore how music relates to your major or to a specific group or societal connection. The topic will preferably be something that relates to how music is personally empowering for you. Your exploration of your chosen topic will take you into the various realms of inquiry, including scientific/scholarly discourse, collective experiences of humanity, and your own experience. In the process of this exploration you will be gathering resources and compiling them into a formal annotated bibliography, gathering expertise about the topic, and sharing what you have discovered with the class in the last two weeks of the quarter.

Required elements: What was your path of inquiry? How does this music or relationship to music influence others or utilize the power of music? How does the topic relate to the 3 realms of knowing including you personally (if appropriate)? For example, how does it empower you, interest you, or otherwise pique your curiosity?

Project Details:

1. Preliminary Bibliography (due week 4) should include at least ten resources and be accompanied with a paragraph or two about your research process (i.e., where did you search, how did you search, etc.) and a list of questions you have formed that you want to answer on your path of inquiry. Note: these resources are ones that look promising, you won’t necessarily need to have read them in detail at this point.

2. Revised bibliography, research process, annotations, etc. (due week 7): Turn in an updated list of resources you intend to use for the project along with any refined research notes (what additional research have you done? etc.) and any remaining questions you have/issues with research. Some of your annotations for your final bibliography should be included in this revision.

3. Class presentations (10-15 minutes) and final annotated bibliographies (presentations weeks 9 & 10). Presentations can be creative and reflect your personal strengths and talents. Examples might include a short talk, a PowerPoint presentation, creation of a film or your own musical composition, an experiential exercise for the class, and so forth. Playing examples of music you have studied are encouraged.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Music Therapy Association. “American Music Therapy Association.” Accessed May 27, 2015. http://www.musictherapy.org.

Association of College and Research Libraries, “Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education,” Last modified January 18, 2000. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency.

Ayot, William. “Anyone Can Sing.” In Small Things That Matter. London: The Well at Olivier Mythodrama Publishing, 2003.

Barrett, Janet R., Claire W. McCoy, and Kari K. Veblen. Sound Ways of Knowing: Music in the Interdisciplinary Curriculum. New York: Schirmer Books, 1997.

Becker, Judith O. Deep Listeners, Music Emotion, and Trancing. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

Brockbank, Anne, and Ian McGill. Facilitating Reflective Learning In Higher Education, 2nd ed. Berkshire, England: Society for Research in Higher Education and Open University Press, 2007.

Brooks, Jacqueline Grennon and Martin G. Brooks. In Search of Understanding: The Case for Constructivist Classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1999.

Burn, Skye. “What Art Offers Leadership: Looking Beneath the Surface.” In Leadership for Transformation. Building Leadership Bridges Series. International Leadership Association. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2011.

Connor, Melinda, Sallyanne Payton and Hansonia Caldwell. “Music for the Soul, Healing for the Brain: Reverse Engineering Neurological Processes with Lessons Learned from the Ring Shout.” YouTube video. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CGv9wfKJOPA.

Cook, Pat Moffitt. Shaman, Jhankri & Nele: Music Healers of Indigenous Cultures. Roslyn, NY: Ellipsis Arts, 1997.

Copland, Aaron. What to Listen for in Music. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1957.

Dabbagh, Nada. “Creating Personal Relevance through Adapting an Educational Task, Situationally, to a Learner’s Individual Interests.” In: Proceedings of Selected Research and Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (18th, Indianapolis, IN, 1996): 159-169.

Duffy, Thomas M. and Pamela L. Raymer. “A Practical Guide and a Constructivist Rationale for Inquiry Based Learning,” Educational Technology 50, no. 4 (2010): 3-15.

Enz, Nicholas J. “Teaching Music to the Non-Major: A Review of the Literature.” Update: Applications of Research in Music Education 32, no. 1 (2013): 34-42.

The Flow Project: Providing Art-infused Leadership. Website. http://theflowproject.org/

Gabrielsson, Alf and Rod Bradbury. Strong Experiences with Music: Music is Much More Than Just Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Gardner, Kay. Sounding the Inner Landscape: Music as Medicine. Rockport, MA: Element Books, 1990.

Glennie, Evelyn. “How to Truly Listen.” TED video. http://www.ted.com/talks/evelyn_glennie_shows_how_to_listen.

Goodchild, Chloe. “The Naked Voice.” Website. http://thenakedvoice.com/home/.

Hallam, Susan and Raymond MacDonald. “The Effects of Music in Community and Educational Settings.” In Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology, edited by Ian Cross and Susan Hallam, 471-480. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Hart, Tobin. “Opening the Contemplative Mind in the Classroom.” Journal of TransformativeEducation 2, no. 1 (January, 2004): 28-46.

Hodges, Donald, and David Conrad Sebald. Music in the Human Experience: An Introduction to Music Psychology. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Jovanov, Emil, and Melinda C. Maxfield, “Entraining the Brain and Body,” In Music, Science and the Rhythmic Brain: Cultural and Clinical Implications. New York: Routledge, 2011: 32-48.

Junda, Mary Ellen. “Sing and Shout! The Study of History and Culture Through Song.” College Music Symposium 53 (December, 2013) http://symposium.music.org/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=10387:ising-and-shout-i-the-study-of-history-and-culture-through-song&Itemid=146

Khan, Hazrat Inayat. The Mysticism of Sound and Music, rev. ed., Boston: Shambhala, 1996.

McFerrin, Bobby, Daniel Levitin, and Audra McDonald. The Music Instinct: Science and Song. DVD. Alexandria, VA: PBS, 2009.

Mithen, Steven J. The Singing Neanderthals: the Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Oliveros, Pauline. Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. New York: iUniverse, 2005.

Oliveros, Pauline. Software For People: Collected Writings 1963-80. Baltimore, MD: Smith Publications, 1984.

Philosophy of Music Education Review 16, no. 1 (Spring, 2008).

Pierce, Deborah L. “Rising to a New Paradigm: Infusing Health and Wellness into the Music Curriculum.” Philosophy of Music Education Review 20, no. 2 (Fall, 2012): 154-76.

Ramsbottom, Nina C. “Landfill harmonic (la orquesta reciclada).” YouTube video. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RFHTIhyNdhk

Reimer, Bennett. Seeking the Significance of Music Education: Essays and Reflections. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education in partnership with MENC, 2009.

Root-Bernstein, Robert Scott and Michèle Root-Bernstein. “Rethinking Thinking.” In Sparks of Genius: the Thirteen Thinking Tools of the World’s Most Creative People. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 2001: 1-13.

Shapiro, Arthur. Case Studies in Constructivist Leadership and Teaching. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2003.

Silver, Harvey F. So Each May Learn: Integrating Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2000.

Skoe, Erika and Nina Kraus. “A Little Goes a Long Way: How the Adult Brain is Shaped by Musical Training in Childhood,” The Journal of Neuroscience 32, no. 34 (August 22, 2012): 11507-11510.

Small, Christopher. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1998.

Small, Christopher. “Musicking—The Meanings of Performing and Listening. A Lecture.” Music Education Research 1, no. 1 (1999): 9-21.

Swayne, Steve. “Pandora’s Box: The Effects of Easy Listening.” YouTube video. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZZCxTT-OGwI

Tan, Siu-Lan, Peter Pfordresher, and Rom Harre. Psychology of Music: From Sound to Significance. Hove: Psychology Press, 2010.

Thompson, Walter. Soundpainting: the Art of Live Composition. Workbook I. Walter Thompson, 2006.

Wan, Catherine Y. and Gottfried Schlaug. “Brain Plasticity Induced by Musical Training.” In The Psychology of Music. 3rd ed., edited by Diana Deutsch, 565-581. London: Academic Press, 2013.

Weil, Andrew. Sound Body, Sound Mind: Music for Healing. Joshua Leeds, composer and producer, frequencies designed by Anna Wise. New York: Tommy Boy Music, 1997. 2 compact discs.

NOTES

1Khan, Mysticism of Sound and Music, 11.

2Mithen, Singing Neanderthals, 278.

3There is a plethora written on the justification for music education. Reimer’s Seeking Significance of Music Education, or the Philosophy of Music Education Review’s 2008 issue devoted to the topic are good resources.

4Enz, “Teaching Music to the Non-Major.”

5Student reflections are from my 2013 and 2014 “Exploring the Power of Music” course.

6Small, Musicking.

7Small, “Musicking, A Lecture,” abstract.

8Reimer, Seeking the Significance of Music Education, 3.

9Pierce, “Rising to a New Paradigm,” 171.

10Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) is an epistemology which describes the fundamental dynamics between the mind, language, and how these interplay with our body and behavior. NLP processes are highly compatible with learning. For details on information literacy see the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Information Literacy Competency Standards.

Social Artistry is the art of enhancing human capacities in the light of social complexity and seeks to bring new ways of thinking, being, and doing to social challenges. One group of social artists is studying the unique capacities of artists which can be applied to leadership. For information, see Burn, “What Art Offers Leadership,” and the Flow Project website.

11I call these the Three Realms of Knowing. See Appendix B for more details.

12There is a significant amount of research regarding the benefits and applications of teaching for personal relevance. Brooks, In Search of Understanding; Dabbagh, “Creating Personal Releavance”; Duffy, Practical Guide; Shapiro, Case Studies; and Silver, So Each May Learn, are good resources.

13Brockbank and McGill, Facilitating Reflective Learning, 335.

14Hart, “Opening the Contemplative Mind,” 38.

15Students generally share more deeply in their written reflections to the instructor than in those posted publically. I continue to search for ways to encourage students to share their views with each other, but this shows the importance of offering reflective outlets beyond the course online discussion board.

16Brockbank and McGill, Facilitating Reflective Learning, 91.

17Hart, “Opening the Contemplative Mind,” 43.

18The University Libraries sponsors a yearly research competition which awards up to $1,000 for student’s completed research projects.

19Root-Bernstein. “Rethinking Thinking,” passim.

20During a stairwell trip, students discovered a wall at the bottom of the stairs had sonorous properties that made an exquisitely resonate musical instrument which created interesting sounds in the reverberant area.

21McFerrin, Music Instinct.

22One of the listening assignments uses the “Symphony of Brainwaves” from Sound Body, Sound Mind: Music for Healing, a collaborative work by Joshua Leeds, producer and composer, Anna Wise, designer of the frequencies, and Andrew Weil, MD. This resource provides a fabulous entry point for discussion on how music can affect the brain along with reading some of the available neuroscience studies.

23Some of the resources by Oliveros, Glennie, and Becker used in class are included in the bibliography.

24In the early versions of the course our main performance medium was singing. I received feedback that the instrumentalists felt left out so I now include a variety of opportunities for students to use their instruments in class, for example, a session in Soundpainting. See Thompson, Soundpainting.

25Guests have included a virtuoso instrumentalist, sound gatherer who helps us play with sound production, a singer-songwriter who uses music to influence the psychological well-being of others, a music therapist, and a music educator who takes the students on a journey to move their ears over to understand another culture.

26Ayot, William, “Anyone Can Sing.”

27See Goodchild, “Singing Field” on The Naked Voice website.

28Juda, “Sing and Shout,” 7.

29While the fact that these bright students are in the Honors Program is an element in their course engagement, I find similar responses, thinking, and assignment quality from other students when using these methods in courses I teach outside of Honors.

30Music on the Four Levels of Awareness is based upon Jean Houston’s Four Levels used for Social Artistry instruction—Sensory/Physical; Psychological/Historical; Mythic/Symbolic; and Unitive/Integral.