Introduction

This paper examines the potential for asynchronous musical collaboration in a chamber ensemble setting. The project was inspired by composer and conductor Eric Whitacre’s virtual choirs which took place from 2009-2014. The choirs, as the composer explained, brought together “singers from around the world and their love of music in a new way through technology” (Whitacre, n.d.)Whitacre, E. (n. d.). About the Virtual Choir. Retrieved from: http://ericwhitacre.com/the-virtual-choir/about . The choirs became a social media phenomenon and grew dramatically in participation. The first ensemble featured 185 participants and the final iteration (embedded below) included over 8,000 submissions (Whicatre, n.d.)Whitacre, E. (n. d.). About the Virtual Choir. Retrieved from: http://ericwhitacre.com/the-virtual-choir/about .

The process for participating was relatively simple. Anyone with a pair of headphones and a computer equipped with a microphone and webcam could take part. Whitacre and his production team used tutorial videos to provide instruction for Virtual Choir participants. The tutorial video (embedded below) illustrated the recording process and was followed by a video of Whitacre conducting the piece to a piano reduction of the vocal parts. After following the instructions, participants would upload their submissions to YouTube to be compiled into an ensemble recording. The compiled video of the performance was released later, and in each instance, viewed millions of times. The barriers to entry were low, and Whitacre’s projects attracted thousands of singers. Since the process required little specialized technological skill or advanced equipment, I became immediately interested in this as a potential model for an asynchronous chamber ensemble experience. I felt this type of interaction could be a compelling means of musical engagement and potentially useful in online music programs.

Online Learning

Online education is a growing component of higher education. A recent report from the Babson Research Group indicated that 25% of college students were enrolled in at least 1 online course. Enrollments in online courses have increased 26% between 2012 and 2014 (Allen & Seaman, 2016)Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Online Report Card – Tracking Online Education in the United States (pp. 1–62). Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group. . The National Center for Education Statistics similarly reported substantial online education enrollment in postbaccalaureate degrees with 25% of students at public or private-nonprofit institutions taking at least 1 online course, and nearly 10% taking part in a degree program offered completely online (U.S. Department of Education, 2016)U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). Digest of Education Statistics, 2015 (NCES 2016-014), Table 311.15. .

It is important to note that online learning is a term that encompasses several instructional models. Online courses may be delivered in either a synchronous or asynchronous format (Bowman, 2013)Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press. . The advantages of each format are significant. Synchronous courses include common meeting times, but allow students to attend class through technologies such as “audio chats and desktop videoconferencing” (Bowman, 2013, p. 6)Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press. from a location of their choosing. Asynchronous courses offer flexibility in both time and location as students interact with “recorded lectures, threaded discussions, individual blogs, class wikis, and e-mail” (p. 6). The added flexibility afforded by online instructional models make these offerings particularly compelling in graduate programs where students may not have the ability to relocate or matriculate full-time (Albert, 2014Albert, D. J. (2014). Online Versus Traditional Master of Music in Music Education Degree Programs: Students’ Reasons for Choosing. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(1), 52–64. ; Bowman, 2013Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press. ; Teachout, 2004Teachout, D. J. (2004). Incentives and Barriers for Potential Music Teacher Education Doctoral Students. Journal of Research in Music Education, 52(3), 234–247. ).

Online Learning in Music

Online degree programs in music are becoming increasingly common with notable growth in graduate music education offerings ( Bowman, 2014Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press. ; Groulx & Hernly, 2010Groulx, T. J., & Hernly, P. (2010). Online Master’s Degrees in Music Education: The Growing Pains of a Tool to Reach a Larger Community. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 28(2), 60–70. ). These programs are compelling for many because they afford the opportunity to continue graduate work without leaving a teaching position (Albert, 2014Albert, D. J. (2014). Online Versus Traditional Master of Music in Music Education Degree Programs: Students’ Reasons for Choosing. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(1), 52–64, Walls, 2008Walls, K. C. (2008). Distance Learning in Graduate Music Teacher Education: Promoting Professional Development and Satisfaction of Music Teachers. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 18(1), 55–66. ), and offer flexibility in scheduling and location (Sherbon & Kish, 2005Sherbon, J. W., & Kish, D. L. (2005). Distance Learning and the Music Teacher. Music Educators Journal, 92(2), 36–41. , Walls, 2008Walls, K. C. (2008). Distance Learning in Graduate Music Teacher Education: Promoting Professional Development and Satisfaction of Music Teachers. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 18(1), 55–66. ) which ameliorate barriers to in-service teachers pursuing post-baccalaureate degrees (Teachout, 2004Teachout, D. J. (2004). Incentives and Barriers for Potential Music Teacher Education Doctoral Students. Journal of Research in Music Education, 52(3), 234–247.). Surveys of faculty attitudes and perceptions of online learning indicate that the academe is increasingly accepting of distance education as of equal or better quality to face-to-face instruction (Allen & Seaman, 2016Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Online Report Card – Tracking Online Education in the United States (pp. 1–62). Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group. t) and students in online music education programs have reported high levels of satisfaction (Kos & Goodrich, 2012Kos, R. P., & Goodrich, A. (2012). Music Teachers’ Professional Growth: Experiences of Graduates from an Online Graduate Degree Program. Visions of Research in Music Education, p. 1–26. ; Walls, K. C. (2008). Distance Learning in Graduate Music Teacher Education: Promoting Professional Development and Satisfaction of Music Teachers. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 18(1), 55–66. ). Additionally, a growing body of research has examined music teaching and learning through distance education in a variety of content areas such as music appreciation, listening, composition, applied music, and music theory (Bowman, 2014Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press. ; span class="tooltip-cms"> Webster, 2007 Webster, P. R. (2007). Computer-based Technology and Music Teaching and Learning: 2000–2005. In L. Bresler (Ed.), International Handbook of Research in Arts Education (Vol. 16, pp. 1311–1330). Dorbrecht, Netherlands: Springer., Webster, 2012 Webster, P. R. (2012). Key research in music technology and music teaching and learning. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 4(2), 115–130. ).

Music educators have debated the merits of online education and in particular what content areas may be best facilitated through online learning (Hebert, 2007, 2008 Hebert, D. (2007). Five Challenges and Solutions in Online Music Teacher Education. Research and Issues in Music Education, 5(1). Hebert, D. G. (2008). Forms of Graduate Music Education: A Response to Kenneth Phillip. Research and Issues in Music Education, 6(1). ; Jorgensen, 2014Jorgensen, E. R. (2014). Face-to-face and distance teaching and learning in higher education: Lessons from the preparation of professional musicians. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 7(2), 181–197.; Philips, 2008 Phillips, K. H. (2008). Graduate Music Education. Research Issues in Music Education, 6, 1–7. ). Phillips (2008), in a discussion of online graduate degrees in music education, felt that knowledge-based courses such as music history or research methods were particularly adaptable to online teaching. However, he also discussed the challenge of developing musical skills through online delivery, specifically noting the lack of ensemble experiences as “an inherent weakness in online degree programs.” Jorgensen (2014) framed her discussion of online teaching around propositional knowledge, the “theoretical understanding of a piece, the circumstances of its composition, and other salient stylistic details,” and procedural knowledge, “the practical skills of being able to play a piece of music” (p. 183). Jorgensen recognized that online learning pedagogy to this point has struggled to facilitate the development of procedural knowledge in music. Research on curricular requirements support both Phillips’s (2008) and Jorgensen’s (2014) contentions. For example, Groulx and Hernly (2010), in a study examining 9 different institutions offering online graduate degrees in music, indicated that only 2 institutions required any work in applied performance or ensembles.

The challenges of facilitating applied instruction at a distance are significant, yet a number of scholars have explored doing so. The body of work related to applied instrumental lessons in classroom and studio instruction settings through online learning (Dammers, 2009Dammers, R. J. (2009). Utilizing Internet-Based Videoconferencing for Instrumental Music Lessons. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 28(1), 17–24., Dye, 2007Dye, K. G. (2007). Applied music in an online environment using desktop videoconferencing (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 325532)., Kruse et al., 2013Kruse, N. B., Harlos, S. C., Callahan, R. M., & Herring, M. L. (2013). Skype music lessons in the academy: Intersections of music education, applied music and technology. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 6(1), 43–60., Orman & Whitaker, 2010Orman, E. K., & Whitaker, J. A. (2010). Time usage during face-to-face and synchronous distance music lessons. American Journal of Distance Education, 24, 92–103.) may be the most notable in this area. Studies on studio instruction involving middle school students (Dammers, 2009Dammers, R. J. (2009). Utilizing Internet-Based Videoconferencing for Instrumental Music Lessons. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 28(1), 17–24., Dye, 2007Dye, K. G. (2007). Applied music in an online environment using desktop videoconferencing (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 325532)., , Orman & Whitaker, 2010Orman, E. K., & Whitaker, J. A. (2010) and graduate students (Kruse et. al, 2013) revealed similar findings. Each study used synchronous instructional formats in which the teacher and learner were separated by distance, but interacted at the same time. The studies most commonly used video conferencing tools such as Skype or iChat. Results indicated that video conferencing was a viable tool for interaction in applied lessons. While technological issues such as inconsistent connections or poor audio/video quality were frustrations in the lessons, they did not prevent students from learning through the interactions. Further, the use of specific idiomatic technologies such as the Yamaha Disklavier, a piano which can reproduce playing from another musician in another location, was found to be a particularly exciting tool for piano instruction (Kruse et al., 2013Kruse, N. B., Harlos, S. C., Callahan, R. M., & Herring, M. L. (2013). Skype music lessons in the academy: Intersections of music education, applied music and technology. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 6(1), 43–60.).

I am aware of no studies that have specifically examined asynchronous ensemble performance through distance learning formats, however, there are promising examples of work using synchronous technologies. For example, video conferencing tools have been used to allow guest composers and clinicians to interact with ensembles (Burrack, 2012Burrack, F. (2012). Using Videoconferencing for Teacher Professional Development and Ensemble Clinics. Music Educators Journal, 98(3), 56–58.; Hoffman & Carter, 2013Hoffman, A. R., & Carter, B. A. (2013). A Virtual Composer in Every Classroom. Music Educators Journal, 99(3), 59–62.). These types of interactions bring performers and composers together more often than would be possible otherwise. Perhaps most germane to the present project are studies related to synchronous performance, a challenge since common videoconferencing tools such as Skype or FaceTime have too much latency to afford simultaneous performance. Latency refers to the amount of delay between when a sound is created and when it is heard by the other person. While the latency in Skype and FaceTime are of little issue to carry on a conversation, the demands for synchronous performance are beyond what the platforms provide. Advanced tools such as LOLA, a technology which allows musicians to perform simultaneously while separated by distance is a promising means of synchronous ensemble performance (Riley, MacLeod & Libera M. Riley, H., MacLeod, R. B., & Libera, M. (2016). Low Latency Audio Video: Potentials for Collaborative Music Making Through Distance Learning. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 34(3), 15–23.). Similarly, telematic operas have been performed simultaneously in opera houses around the world using advanced Internet 2 technology (Shoger, 2012). Each of these platforms for collaboration require technology which would be unavailable away from a university campus. While they represent promising technologies, each platform requires participants to travel to a specific location to participate, negating many of the key benefits of online learning.

Asynchronous musical collaboration in the manner of the present study is an emerging area of inquiry. Cayari (2016), similarly inspired by Whitacre’s (n.d.) Virtual Choir projects, examined one-person virtual choral ensembles. These ensembles involved a lone musician performing all the parts to a choral work and completing the technological elements such as recording, synchronizing, and posting of materials. Findings indicated that “performing in or creating a virtual vocal ensemble requires some of the same skills one would use in a synchronic choir” (p. 370) while also fostering the development of technological and production skills. One person vocal ensembles are plentiful on YouTube and are an example of some of the broader musical engagements available through participatory culture in music education (Tobias, 2013Tobias, E. S. (2013). Toward Convergence: Adapting Music Education to Contemporary Society and Participatory Culture. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 29–36.). However, I wish to draw a contrast between the Virtual Tuba Quartet, Whitacre’s Virtual Choirs, and one-person virtual vocal ensembles as explored by Cayari (2016).

I specifically sought to develop a collaborative ensemble which would prepare music similar to that of a face-to-face chamber ensemble. To do so requires collaboration among multiple persons and a system in which musical performances would be recorded and improved upon, much as they would in a typical ensemble. This is a unique facet of this project. For example, participants in Whitacre’s Virtual Choirs engagement with the project ended upon the submission of their recording. They did not receive feedback from other ensemble members or an ensemble leader. Similarly, in Cayari’s (2016) examples, virtual ensembles were created by one musician performing multiple parts with few examples of asynchronous collaboration. While Cayari found that sole creation of ensemble performances afforded participants to “express their creativity on their own terms” (p. 174), one of my goals for this group was to facilitate a collaborative musical performance through the interactions of several musicians.

I chose a chamber ensemble setting for this project both for the pragmatic reason of interacting with a small group of collaborators and because of the specific benefits available through chamber ensemble participation. Chamber ensembles have been found to offer opportunities for participants to interact through the process of preparing a performance (Berg, 1997Berg, M. H. (1997). Social construction of musical experience in two high school chamber music ensembles (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 9731212)) and develop musical skills as participants work with more independence than may be afforded in a large ensemble environment (Schmid, 2000Schmid, W. (2000). Challenging the status quo in school performance classes: New approaches to band, choir, and orchestra suggested by the music standards. In B. Reimer. (Ed.), Performing with Understanding: The Challenge of the National Standards for Music Education. Reston, VA: MENC – The National Association for Music Education.). Additionally, the potential for musical development and learning has been found to be significant in chamber ensemble settings (Carmody, 1988Carmody, W. J. (1988). The effects of chamber music experience on intonation and attitudes among junior high school string players (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 0563729); Larson, 2010Larson, D. D. (2010). The Effects of Chamber Music Experience on Music Performance Achievement, Motivation, and Attitudes Among High School Band Students (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 3410633)., Stabley, 2000Stabley, N. C. (2000). The effects of involvement in chamber music on the intonation and attitude of 6th and 7th grade string orchestra players (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 3000625).).

Technological Mediation

Regarding mediation, Jones and Hafner (2012) explain: “a medium is something that stands in between two things or people and facilitates interaction between them” (p. 1). Considering technology’s role in online learning and how experiences are mediated allows us to “acknowledge the interaction between technology and context” (Ruthmann et al., 2015; p. 126Ruthmann, S. A., Tobias, E. S., Randles, C., & Thibeault, M. (2015). Is it the technology? Challenging Technological Determinism in Music Education. In C. Randles (Ed.), Music education: Navigating the future, 122-138. New York: Rutledge.). For example, in the context of facilitating studio lessons through videoconferencing technology, Dammers (2009) explained, “the challenges of the online format prevented the videoconference environment from becoming transparent or forgotten by the participants” (p. 22). Technology similarly mediates this project. Comparisons to face-to-face ensemble experiences are unavoidable, but it is my hope that such comparisons recognize the role of technology in mediating this experience. In this project, participants’ primary means of interaction were through their computers asynchronously. While they had options for communicating with one another through annotation of sound recordings, text comments, and video recordings, each option was mediated by the affordances and constraints of the various technologies employed.

Affordances can be thought of “in terms of the possibilities they offer for action” (Ruthmann, et al., 2015, p. 127Ruthmann, S. A., Tobias, E. S., Randles, C., & Thibeault, M. (2015). Is it the technology? Challenging Technological Determinism in Music Education. In C. Randles (Ed.), Music education: Navigating the future, 122-138. New York: Rutledge. ) while constraints refer to “the things we cannot do with it” (Jones & Hafner, 2013, p. 9Jones, R. H., & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding digital literacies: A practical introduction. London: Routledge. ). Each technology’s affordances and constraints influenced the project. For example, text comments afforded the ability to share thoughts and comments among participants. Conversely, text comments also have the constraint of not including tone of voice or the nuances of speech. A musician in a face-to-face ensemble can speak to other ensemble members with the affordances of the others perceiving her tone of voice, inflection, and cadence, however her discussion is not preserved in a manner that can be viewed later by ensemble members outside of rehearsal. In this sense, both face-to-face and online ensembles are influenced by the affordances and constraints of how they communicate.

I offer this brief discussion of mediation, affordances, and constraints as a means to contextualize the details of this project. I encourage readers to avoid seeing this type of performance experience or this project as an attempt to replace the face-to-face ensemble with an online variant, but rather to explore how an ensemble experience can be mediated asynchronously through technology.

The Project

Overview

The purpose of this project was to determine if an asynchronous ensemble experience could be facilitated using free and low-cost tools. I formed the Virtual Tuba Quartet to investigate the potential for asynchronous musical collaboration. This group prepared two pieces of repertoire over the course of 12 weeks in the spring and summer of 2013.

Participants were expected to own a recording device and a personal computer. Both Apple and PC computers were used and there were no hardware parameters recommended. Recording devices were generally affordable handheld recorders by manufacturers such as Zoom and Tascam and cost between $80 and $150. I used free web-based tools to facilitate collaboration including WordPress as a project website, SoundCloud for sharing recordings, Dropbox for sending and receiving files, and Scribd for distributing parts. Participants used personal headphones while recording.

In the following section I will describe how the Virtual Tuba Quartet functioned. I will begin with a broad explanation of the recording and submission process. I will then provide information about the participants in the group, followed by a discussion of some of the specific challenges related to the preparation of repertoire, selection of repertoire, and building community.

Process

The Virtual Tuba Quartet was an asynchronous ensemble allowing participants to create their contributions at times and places of their choice. Literature related to distance learning recommends that instructors make efforts to build community in their classes (Bowman, 2013Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press.; Drouin & Vartanian, 2010Drouin, M., & Vartanian, L. R. (2010). Students’ Feelings of and Desire for Sense of Community in Face-to-Face and Online Courses. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 11(3), 147–159.; Rovai, Wighting, & Lit, 2005Rovai, A. P., Wighting, M. J, & Liu, J. (2005). School climate: Sense of classroom and school communities in online and on-campus higher education courses. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6(4), 361–374.; Shackelford & Maxwell, 2012Shackelford, J. L., & Maxwell, M. (2012). Sense of Community in Graduate Online Education: Contribution of Learner to Learner Interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 228-249.; Sadera, Robertson, Song, & Midon, 2009Sadera, W. A., Robertson, Song, L., & Midon, M. N. (2009). The Role of Community in Online Learning Success. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 277-284.). Heeding this advice, I first asked participants to make a brief video in which they introduced themselves to the group. The videos were uploaded to the course website and reviewed by the participants. This allowed members of the group to develop more of a connection with one another and humanize their interactions. Following the introductory videos, I provided members of the group with parts and a reference recording to their first musical selection, an arrangement of Flourish for Wind Band by Vaughan Williams which I had adapted for tuba quartet. The reference recording included a MIDI track to the work synchronized to a metronome click that played throughout. The musicians were then asked to submit their individually recorded parts during the following week.

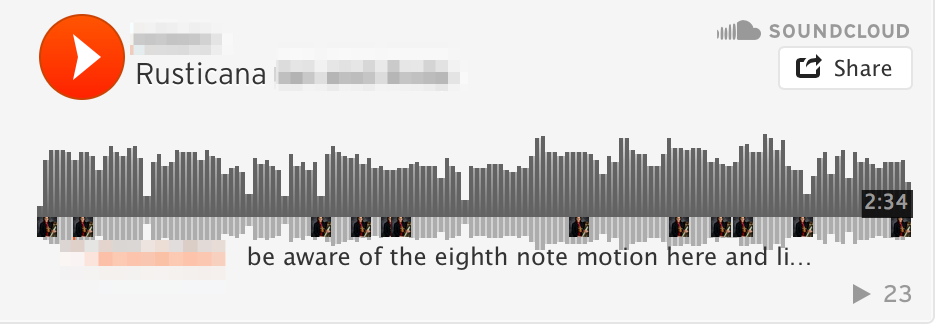

After musicians submitted their parts I compiled the recordings into a single audio file and adjusted volumes so that each part could be heard clearly. I added basic volume automation to tracks so that the balance would be clear throughout the recording. I edited using Apple’s Logic Pro X software, a digital audio workstation. Even though I used a professional application, the process could be done in most any audio editing software. I then uploaded the compiled track to SoundCloud and embedded it in a post on our group website. Once the ensemble recording was available I emailed all of the participants inviting them to listen to the recording and provide each other feedback. Participants were expected to use the feedback to refine their performances in a new set of recordings which were due a week later. Participants repeated this cycle three times after which I invited a chamber ensemble coach to provide feedback. The coach listened to the recordings and provided annotations to the sound file within the SoundCloud web player. I then emailed the participants to review the coach’s feedback and prepare their final version of the piece.

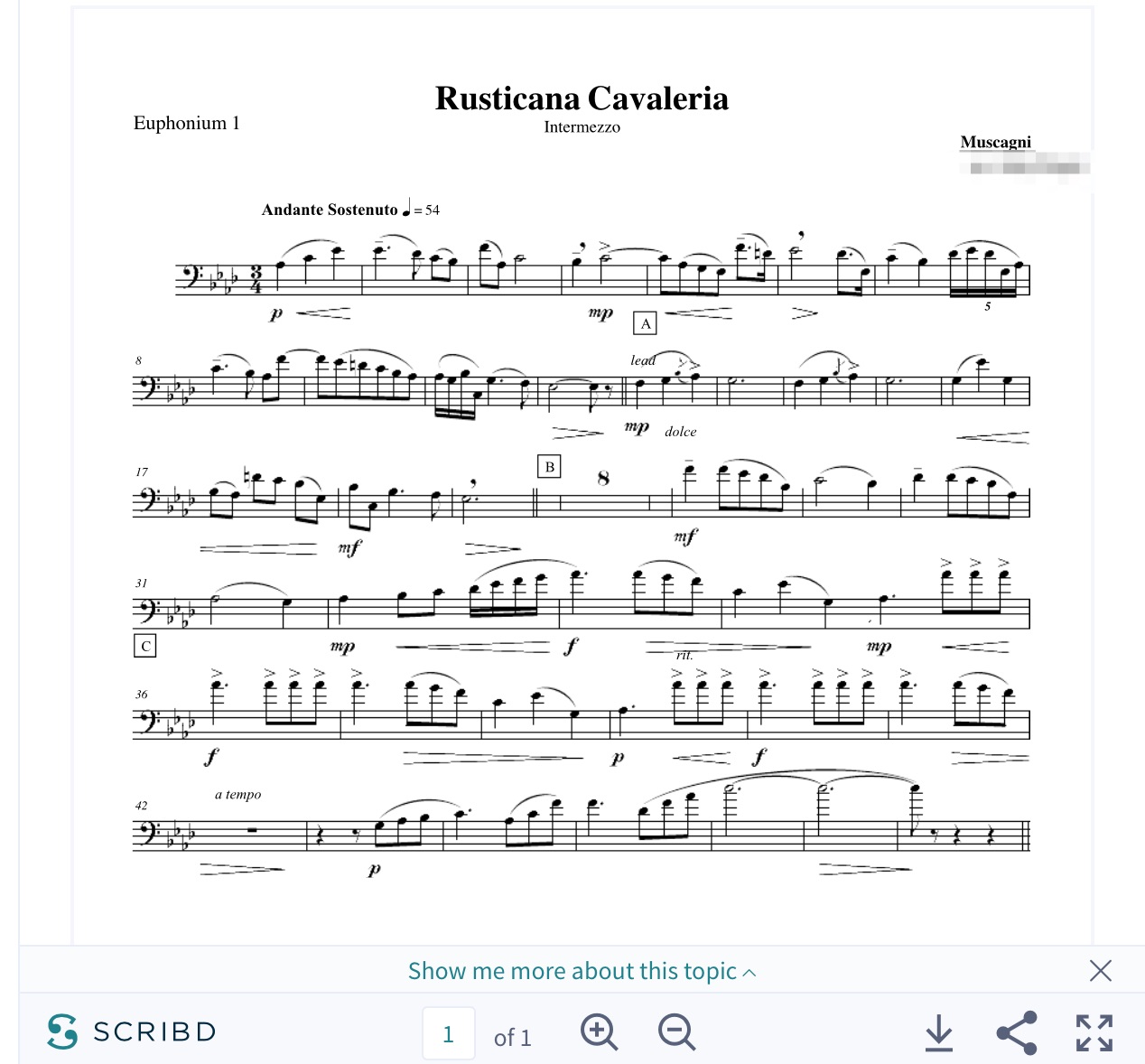

After four iterations, the group had produced a recording of Flourish for Wind Band with which they were content (excerpt embedded below). We then met as a group via Skype, discussed our experiences with the first round of recordings, and considered what repertoire we might pursue next. I compiled a list of the musicians’ recommendations and uploaded videos and recordings of the pieces to our website for discussion. After participants had the opportunity to share their opinions via comments on the website, the group decided on an arrangement of Mascagni’s Rusticana Cavaleria which Adam, the 1st euphoniumist, had arranged.

Adam sent me a score and parts to the new piece, which I uploaded to our website. I then began the process of preparing a clicktrack and MIDI recording as a reference for the other musicians to use. When complete, I shared the new reference track with the group so they could begin their recordings. We followed the same process for submissions and feedback as we had before. Participants were asked to submit a recording weekly for 3 weeks making improvements based on the feedback that was offered. The ensemble coach then offered suggestions to the ensemble and the group made a final iteration of the piece. The process was again successful in producing a collaborative recording of the musical work and the participants were pleased with the final recording.

Participants

Participants were selected as a convenience sample (Maxwell, 2013). I had known several of the musicians prior to the project and one ensemble member was recommended to me via a mutual friend. All names in this article are pseudonyms. Each participant had pursued advanced study in euphonium or tuba performance. Adam, who played first euphonium, recently completed his doctoral degree in euphonium performance and was living in Dallas, Texas. Gilbert lived in the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area and was the second euphoniumist. Gilbert was pursuing an undergraduate music education degree, had studied privately on euphonium throughout high school, and performed in local semi-professional wind and brass bands. Collin, who played second tuba, lived in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. He had recently completed a graduate degree in music education, was active as a gigging musician on sousaphone, and was employed as a K12 music educator. Finally, Greg, who played first tuba, lived in Austin, Texas where he had an active low brass studio and worked as an instructor at an area high school. He held a graduate degree in tuba performance.

For the purposes of this project, I felt advanced players would help me determine if I was facilitating the ensemble in a way that made sense technologically. If one of the players had a musical challenge, such as not being able to play in time, this could have obfuscated the process. I may not have been able to tell if the ensemble was struggling due to technical challenges, or if it was musical skills that needed to be developed by some of the participants. With that said, I do believe that this process would be appropriate for musicians at many levels of proficiency, provided they were capable of performing along to a metronome or clicktrack recording.

The ensemble coach was a tuba and euphonium professor at a major school of music. Her background included substantial professional chamber ensemble experience and decades of experience mentoring student ensembles. She provided feedback to the ensemble on each of their recordings and had access to all of the online resources throughout the project. Prior to reviewing recordings, the coach reviewed the group’s project on the website and became familiar with the musicians through their introduction videos.

I participated as a facilitator of the project. I was responsible for providing the materials to the group and facilitating their interactions. I selected the technological platforms which were used, developed the basic format for interaction, alerted musicians to the availability of new materials. While I did not offer any specific musical feedback, this role might be similar to that of a technology facilitator or specialist in an online learning program.

Recording Process

For this project to function, participants needed a reference track to record along to. Without a reference track it would have been nearly impossible to guarantee the parts could be synchronized as some may have added rubato or interpretations that were different than the rest of the ensemble. I felt we would be most successful if the reference track included elements of the piece that was being recorded as well as a metronome click to help participants stay in time. This would allow participants to record with some sense of context even if it was their first time contributing to the piece. For the reference tracks, I borrowed much of the process Eric Whitacre used in the Virtual Choir projects. I made a tutorial recording (embedded below) which guided the musicians through creating their recordings. I asked the musicians to start their submissions with the reference recording playing aloud so it could be heard by the recorder. The first sound that played was a loud beep. The beep provided a clear starting point that I could use to synchronize the recordings. Following the beep, the click track started. During this time participants inserted their headphones into their devices so they could hear the reference track as they performed and the recorder only picked up the sound of their instrument.

Preparation of Repertoire

The process of preparing repertoire for the ensemble was substantial in comparison to a face-to-face experience. For example, in a face-to-face chamber ensemble the only preparation required after selecting a piece of music is the distribution of sheet music, which could take place relatively easily at a planned group rehearsal. In a virtual ensemble, parts must be distributed and a reference track has to be made before the ensemble can record.

Part distribution was the simpler of the technological challenges. Since each of our selections were arrangements that either I or Adam had completed, we had access to the files in our notation software. For each piece we printed parts as .pdf files which I uploaded to the document sharing website, Scribd (pictured left). I could have simply emailed the parts to the musicians, but I chose Scribd because it allowed the parts to be embedded in the website posts and gave each musician the ability to play off of their screen or to print their part. This same functionality is available today with services such as Google Drive.

The preparation of the reference track was more complex, but was simplified significantly because we had access to the notation files. To start I added a clave part to each arrangement to serve as the click track. I placed clave notes on each beat for the duration of the piece and then exported an audio file of notation software’s MIDI sounds with the click. For our first piece, this served as the reference track since the piece had little variation in tempo. For the second piece, the process was more involved.

Adam’s arrangement of Rusticana Cavaleria required a great deal of interpretation. The lyrical nature of the work lent itself to judicious amounts of rubato and it was important that one of the ensemble members provided the interpretation. I asked Adam if he would like to offer a recording of the first euphonium part that included his overall wishes regarding tempo and rubato. I had added the clave part to the arrangement, and using Adam’s recording as a reference I used the “Tapping a Tempo” function in Finale to synchronize the MIDI playback to Adam’s performance. This process allows the user to tap the space bar to indicate speed of beats throughout a piece of music. After a couple of tries I had a workable version that took less than 30 minutes to produce. I then exported the audio file from the notation software and synchronized it in my digital audio workstation with Adam’s recording. I mixed the recording so the MIDI sounds were relatively quiet and Adam’s part and the click were most audible. I then exported the file and embedded it on the project website for the participants to begin their recordings (excerpt of reference track embedded below).

This process may seem relatively laborious, but in each instance, it took less than 2 hours to have a workable reference track. Given that each of our selections was less than 3 minutes in length, this likely affected the amount of time needed. Longer repertoire might require more work. However, even after going through the process twice, I believe I could complete the process more efficiently now. I recognize my background in music technology likely made this process quicker for me than it might be for a less experienced facilitator. This investment of preparation time also complicates the process of selecting music. Because it requires such a substantial amount of time and energy, it is difficult to easily try out or sightread new pieces as a group.

Selection of Repertoire

Repertoire selection was an interesting process for the group. In order to get the group started, I felt it was important that I had a piece ready from the start. I chose Flourish for Wind Band largely because I knew it was relatively simple, contained very little tempo fluctuation, and would allow for us to test the technological process without musical challenges.

As the group decided on its second piece, they were aware of the technological challenges. They brainstormed repertoire and discussed challenges related to interpretation and tempo that were a part of our group due to the manner that technology mediated our collaboration. Pieces with multiple tempo changes were difficult to accomplish and similarly, longer works presented challenges because it would be more difficult for the musician to create a singular good take of their part. While we never discussed if participants could or should edit their parts prior to submitting them, only one participant chose to edit together different takes for his contributions. Despite the technological challenges the group ultimately selected a piece with significant tempo fluctuations indicating that these challenges could be surmounted. Still, a consistent concern for the group was not only finding engaging and interesting repertoire, but also works that would be suitable for this asynchronous collaboration model.

Building Rapport and Facilitating Feedback

Participants were asked to create brief videos at the beginning of the project to introduce themselves to each other. This proved to be a valuable exercise and one which the musicians wished we had done more throughout the project. They appreciated the opportunity to “humanize” the group and even asked for more information from one another. For example, Collin asked if other musicians would share pictures of where they record and their instruments to give him an idea of where the group performed.

Participants had two means to offer feedback, text comments on the group website, or comments directly on the sound file from SoundCloud (see below). They tended to favor offering brief text comments which focused on elements such as intonation, articulation, and time. They rarely gave direct feedback to other members of the group and most often offered global recommendations for the ensemble. While everyone did contribute to the commentary, the older members of the ensemble, particularly Adam, dominated the discussion. This may be attributable to Adam being the arranger of one of the works and having the most experience performing in tuba quartets.

Our ensemble coach preferred to use the SoundCloud comments to provide feedback. Her commentary was specific and mentioned the musicians and their specific parts (an example of SoundCloud annotations are pictured below). The annotations of the audio file were particularly helpful in her commentary because they allowed her to make comments such as “be careful of intonation here” without having to type out where exactly she was referring to. This made her participation relatively efficient and the feedback was effective for the participants.

Ultimately, the group felt connected to one another through the ensemble, but characterized it as different than what they had experienced in a face-to-face ensemble. Some reported feeling constrained by the technology and wished “to just be in the room with the others” while others acknowledged that “this is great because if I wasn’t in this tuba quartet I wouldn’t be in any tuba quartet.” Still, the models for interaction and facilitating feedback were effective as participants felt they had revisions to make after each iteration of the recording.

Discussion

The purpose of this project was to determine if an asynchronous ensemble experience could be facilitated using free and low-cost tools. The Virtual Quartet was successful. An excerpt of their final recording of Rusticana Cavaleria is embedded below. Participants were proud of the recordings they produced and felt they had a rewarding experience. In the following section I will briefly discuss this project as a viable model for ensemble experiences in online music programs, new technologies that may make this type of collaboration easier going forward, the capacity to develop musical skills (Phillips, 2008Phillips, K. H. (2008). Graduate Music Education. Research Issues in Music Education, 6, 1–7.) or procedural knowledge (Jorgensen, 2012Jorgensen, E. R. (2014). Face-to-face and distance teaching and learning in higher education: Lessons from the preparation of professional musicians. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 7(2), 181–197.) through this type of experience, and the manner in which technology mediated this experience.

A Model for Asynchronous Ensembles

The Virtual Tuba Quartet could function as a viable model for facilitating ensemble experiences in online learning programs. However, there are some important facets of the project that should be considered. Perhaps most important is the need for faculty professional development related to the technological skills required to facilitate an asynchronous ensemble.

Online teaching requires the development of technological skills that are appropriate to the medium (Bowman, 2013Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press.) and facilitating an online ensemble is no different. When compared to a face-to-face chamber ensemble, this project was labor intensive and required significant technological skills. For example, to prepare a piece of repertoire for the group I needed to be comfortable with basic notation software and somewhat skilled in audio editing. To compile participants’ recordings, I needed a cursory understanding of balancing and exporting audio through a digital audio workstation. Sharing materials with the ensemble demanded an understanding of posting and sharing different types of media (audio, video, documents, text). While I would not characterize any of these skills as advanced, when combined, they are not insignificant. Additionally, much of this work has to be done in advance of student involvement.

It took me approximately 90 minutes of work each week to compile participants’ submissions and post relevant materials for the members of the group to view. This part of the process could be accomplished by a technology facilitator who did not play an instructional role in the group, but this would additionally require significant coordination with faculty and students. Faculty members and administrators should consider this as they determine if this type of ensemble would be appropriate. Finally, the technological component of this type of ensemble could also be delegated to students within the ensemble. This would provide an opportunity for them to develop technological skills and be consistent with some of the learning benefits experienced by YouTube creators (Cayari, 2016Cayari, C. (2016). Virtual Vocal Ensembles and the Mediation of Performance on YouTube (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 10301985)) and more broadly within digital and participatory culture (Tobias, 2013Tobias, E. S. (2013). Toward Convergence: Adapting Music Education to Contemporary Society and Participatory Culture. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 29–36.).

Technological Advances

In the 3 years since this project took place a number of platforms have emerged which may permit this type of asynchronous collaboration more easily. I will briefly discuss the affordances and constraints of two applications, Soundtrap and Bandhub, which have the potential to simplify asynchronous collaboration.

Bandhub is an online platform for musical collaboration. After creating an account, participants can either start or join a “collab,” Bandhub’s term for a collaborative project. To start a collaboration, a user is required to select a reference video from YouTube, much like the reference tracks were used in this project. After selecting a YouTube video, participants record directly into their browser as the video plays. Bandhub then processes and posts the video where it’s volume can be adjusted and played along with other tracks. Collaborators can post comments to one another on a message board at the bottom of each project and provide feedback and other comments.

Bandhub’s platform affords a substantial amount of collaboration. The platform does all of the technological work related to recording and synchronizing the tracks, however, the sound balancing tools are relatively crude. For example, when I compiled tracks for the Virtual Tuba Quartet I was able to adjust volumes throughout the tracks. If one section required more 1st tuba and less euphonium I could make that adjustment and then again change the balance later. With Bandhub only a global track volume could be set, meaning performers would have to adjust their volumes as they record in relationship to the volumes they anticipate from the other ensemble members. Additionally, since collaborators record their submissions through Bandhub’s application on their computers they have little opportunity to edit or alter their submissions before adding it to a mix. This affords a great deal of ease-of-use for musicians, but does so at the expense of the ability to edit, compile, and upload a more refined track.

Soundtrap has perhaps the most promise for this type of collaboration. Soundtrap is a web-based digital audio workstation. It has many of the features of modern audio editing software packages such as Logic Pro, GarageBand, and ProTools. Perhaps most enticing about this application is that it has the ability to share projects with other collaborators in a manner similar to Google Docs allowing for multiple musicians to interact and collaborate on the same document from different locations.

Using Soundtrap, a musician could upload a reference track and then share their project with all members of an ensemble. Participants could then record their parts directly in to the project and have the ability to edit and refine their contributions. Recordings are available for all participants to hear as they are added to the project. For example, if Adam was the first to record along to the reference track, his contribution would be available for Collin as he recorded later. Each musician would have the benefit of hearing the contributions of others. Additionally, feedback can be provided through written comments and ensemble members can video conference with one another as they work on the recordings (latency still prevents participants from recording or performing simultaneously).

Soundtrap allows for musicians to take control of the technological facets of the project and lessens the need for much of the work I did in the Virtual Tuba Quartet. While the preparatory work related to producing a reference recording and distributing parts would remain, the need to compile and edit weekly submissions would be dramatically less making this a particularly exciting technology. I plan to use Soundtrap in future iterations of this project.

Procedural Knowledge and Technological Mediation

I wish to return to Phillips’s (2008) and Jorgensen’s (2013) contentions that online learning has yet to find a means to facilitate the development of performing skill or procedural knowledge, “the practical skills of being able to play a piece of music” (p. 183). Like Cayari’s (2016) investigation of one-person choral ensembles, the present project illustrates a rewarding ensemble experience that relied on and developed procedural knowledge and musical skills similar those in a synchronous ensemble. Like a face-to-face chamber ensemble, the musical demands of participants were significant. They had to perform with appropriate style, intonation, interpretation, blend, respond to other performers’ contributions, and discuss musical performances in an advanced and nuanced manner.

The asynchronous form of collaboration also brought specific affordances which facilitated unique pedagogical advantages. For example, through their interactions participants were more analytical and reflective in recommending changes than they might be in a typical rehearsal conversation. Similarly, the formalized opportunities to listen and reflect upon performances through the weekly recordings is often absent from face-to-face experiences. I believe the participants prepared with more awareness of the entire piece of music and brought a broader perspective of the overall ensemble sound due to recording process.

The possibilities for facilitating applied music instruction through online learning programs are becoming increasingly robust. Much like was found in studies of synchronous applied lessons at a distance (Dammers, 2009Dammers, R. J. (2009). Utilizing Internet-Based Videoconferencing for Instrumental Music Lessons. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 28(1), 17–24., Dye, 2007Dye, K. G. (2007). Applied music in an online environment using desktop videoconferencing (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 325532). , Kruse et al., 2013Kruse, N. B., Harlos, S. C., Callahan, R. M., & Herring, M. L. (2013). Skype music lessons in the academy: Intersections of music education, applied music and technology. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 6(1), 43–60.; Orman & Whitaker, 2010Orman, E. K., & Whitaker, J. A. (2010). Time usage during face-to-face and synchronous distance music lessons. American Journal of Distance Education, 24, 92–103. ) this project was found to be a rewarding means of musical interaction. Online music programs have viable options for teaching applied music in both studio and ensemble settings potentially affording the possibility to broaden curricular offerings and requirements (Groulx & Hernly, 2010).

This project was mediated by technology. These ensemble members were never in the same room at the same time, they never had a formal rehearsal, yet they produced two collaborative recordings. It is important to recognize the “interaction between technology and context” (Ruthmann et al., 2015; p. 126Ruthmann, S. A., Tobias, E. S., Randles, C., & Thibeault, M. (2015). Is it the technology? Challenging Technological Determinism in Music Education. In C. Randles (Ed.), Music education: Navigating the future, 122-138. New York: Rutledge.). The product of this group was similar to that of a face-to-face ensemble, but the process of being in this ensemble was quite different. These musicians created their recordings alone with only a reference recording to listen to. They were not making in-time reactions to the other musicians, but were instead offering commentary and analysis based upon weekly postings on the course website. To be a part of the ensemble, these musicians went to their computers instead of a rehearsal room. I offer these comparisons to illustrate how this project differs from a face-to-face ensemble, but I still hope that readers will see this as a complementary, but different type of ensemble experience. It relied on many of the same musical skills, but those skills had to be developed based upon the affordances of the technology.

As online learning continues to grow, music programs should explore more means of musical instruction mediated by technology. While fundamentally different than a face-to-face ensemble, the Virtual Tuba Quartet offers a viable model for asynchronous collaboration in a chamber ensemble setting that offers many of the advantages of online learning. Technological advances will make this type of musical collaboration increasingly easy and afford more people the opportunity to develop musical skills and procedural knowledge. Ongoing research in asynchronous musical collaboration can refine technological and pedagogical practices that support technologically-mediated applied music instruction. The potential for rewarding musical engagement is promising and it is my hope that more musicians will investigate this type of collaboration going forward.

References

Albert, D. J. (2014). Online Versus Traditional Master of Music in Music Education Degree Programs: Students’ Reasons for Choosing. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(1), 52–64.

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Online Report Card – Tracking Online Education in the United States (pp. 1–62). Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group.

Bowman, J. (2014). Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press.

Berg, M. H. (1997). Social construction of musical experience in two high school chamber music ensembles (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 9731212)

Burrack, F. (2012). Using Videoconferencing for Teacher Professional Development and Ensemble Clinics. Music Educators Journal, 98(3), 56–58.

Carmody, W. J. (1988). The effects of chamber music experience on intonation and attitudes among junior high school string players (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 0563729)

Cayari, C. (2016). Virtual Vocal Ensembles and the Mediation of Performance on YouTube (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 10301985)

Dammers, R. J. (2009). Utilizing Internet-Based Videoconferencing for Instrumental Music Lessons. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 28(1), 17–24.

Drouin, M., & Vartanian, L. R. (2010). Students’ Feelings of and Desire for Sense of Community in Face-to-Face and Online Courses. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 11(3), 147–159.

Dye, K. G. (2007). Applied music in an online environment using desktop videoconferencing (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 325532).

Groulx, T. J., & Hernly, P. (2010). Online Master’s Degrees in Music Education: The Growing Pains of a Tool to Reach a Larger Community. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 28(2), 60–70.

Hebert, D. (2007). Five Challenges and Solutions in Online Music Teacher Education. Research and Issues in Music Education, 5(1).

Hebert, D. G. (2008). Forms of Graduate Music Education: A Response to Kenneth Phillip. Research and Issues in Music Education, 6(1).

Hoffman, A. R., & Carter, B. A. (2013). A Virtual Composer in Every Classroom. Music Educators Journal, 99(3), 59–62.

Jones, R. H., & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding digital literacies: A practical introduction. London: Routledge.

Jorgensen, E. R. (2014). Face-to-face and distance teaching and learning in higher education: Lessons from the preparation of professional musicians. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 7(2), 181–197.

Kos, R. P., & Goodrich, A. (2012). Music Teachers’ Professional Growth: Experiences of Graduates from an Online Graduate Degree Program. Visions of Research in Music Education, p. 1–26.

Kruse, N. B., Harlos, S. C., Callahan, R. M., & Herring, M. L. (2013). Skype music lessons in the academy: Intersections of music education, applied music and technology. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 6(1), 43–60.

Larson, D. D. (2010). The Effects of Chamber Music Experience on Music Performance Achievement, Motivation, and Attitudes Among High School Band Students (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 3410633).

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative Research Design (Third). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Orman, E. K., & Whitaker, J. A. (2010). Time usage during face-to-face and synchronous distance music lessons. American Journal of Distance Education, 24, 92–103.

Phillips, K. H. (2008). Graduate Music Education. Research Issues in Music Education, 6, 1–7.

Riley, H., MacLeod, R. B., & Libera, M. (2016). Low Latency Audio Video: Potentials for Collaborative Music Making Through Distance Learning. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 34(3), 15–23.

Rovai, A. P., Wighting, M. J, & Liu, J. (2005). School climate: Sense of classroom and school communities in online and on-campus higher education courses. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6(4), 361–374.

Ruthmann, S. A., Tobias, E. S., Randles, C., & Thibeault, M. (2015). Is it the technology? Challenging Technological Determinism in Music Education. In C. Randles (Ed.), Music education: Navigating the future, 122-138. New York: Rutledge.

Sadera, W. A., Robertson, Song, L., & Midon, M. N. (2009). The Role of Community in Online Learning Success. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 277-284.

Schmid, W. (2000). Challenging the status quo in school performance classes: New approaches to band, choir, and orchestra suggested by the music standards. In B. Reimer. (Ed.), Performing with Understanding: The Challenge of the National Standards for Music Education. Reston, VA: MENC – The National Association for Music Education.

Shackelford, J. L., & Maxwell, M. (2012). Sense of Community in Graduate Online Education: Contribution of Learner to Learner Interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 228-249.

Sherbon, J. W., & Kish, D. L. (2005). Distance Learning and the Music Teacher. Music Educators Journal, 92(2), 36–41.

Shoger, S. (October 29, 2012). Opera on a global scale: Auksalaq at IUPUI. Retrieved from: http://m.nuvo.net/indianapolis/opera-on-a-global-scale-auksalaq-at-iupui/Content?oid=2505277

Stabley, N. C. (2000). The effects of involvement in chamber music on the intonation and attitude of 6th and 7th grade string orchestra players (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 3000625).

Teachout, D. J. (2004). Incentives and Barriers for Potential Music Teacher Education Doctoral Students. Journal of Research in Music Education, 52(3), 234–247.

Tobias, E. S. (2013). Toward Convergence: Adapting Music Education to Contemporary Society and Participatory Culture. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 29–36.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). Digest of Education Statistics, 2015 (NCES 2016-014), Table 311.15.

Walls, K. C. (2008). Distance Learning in Graduate Music Teacher Education: Promoting Professional Development and Satisfaction of Music Teachers. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 18(1), 55–66.

Webster, P. R. (2007). Computer-based Technology and Music Teaching and Learning: 2000–2005. In L. Bresler (Ed.), International Handbook of Research in Arts Education (Vol. 16, pp. 1311–1330). Dorbrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Webster, P. R. (2012). Key research in music technology and music teaching and learning. Journal of Music, Technology, and Education, 4(2), 115–130.

Whitacre, E. (n. d.). About the Virtual Choir. Retrieved from: http://ericwhitacre.com/the-virtual-choir/about