Abstract

Music faculty members have unique roles in the academy with the dual emphases on artistic and scholarly work expected in their teaching, service, and research. We analyzed responses from a national sample of ranked music professors to the Music Faculty Questionnaire: Faculty Vitality and Organizational Conditions, to see how music faculty apply job crafting in their day-to-day work to enhance revitalization. Results show that active engagement in job crafting, through changing job responsibilities, allowing for time off, allocating time congruent to their role commitment, and creating collaborative experiences is associated with revitalization. Further, we identify job crafting in teaching, research, and service as precursors to increased success in faculty work.

The Problem

Understanding the nature, productivity, and assessment of music faculty work poses a unique challenge. In addition to the three primary roles (i.e., research, teaching, and service) in which faculty typically engage, music faculty roles involve added complexity. For example, music faculty teaching not only involves classroom teaching of academic subject matter, but also directing ensembles (e.g., choir, orchestra, symphonic band, marching band, chamber music, opera, jazz ensemble) and offering individualized applied music training sessions. The research of music faculty also goes beyond the traditional publication of articles and presentation of research to include developing new works and performing them in public platforms. The artistic nature of musical performance requires an intensive and narrow focus, often requiring many hours of practice in isolation, which can inhibit the musician from engaging in expected academic citizenship activities. Similarly, service roles frequently include performing at institutional events and in community functions, in addition to the service in professional organizations, university committees, and student advising.

The increased complexity in each of the three traditional roles of faculty work takes its toll on music faculty and has the potential to lead to burnout (Bernhard, 2007Bernhard, H.C.II (2007). A survey of burnout among university music faculty. College Music Symposium, Vol. 47, pp.117-126. ; Hamann et al., 1988Hamann, Donald L., Daugherty, Elza, and Sherbon, James (1988). Burnout and the College Music Professor: An Investigation of Possible Indicators of Burnout Among College Music Faculty Members. Council for Research in Music Education. Bulletin No. 98. Fall, 1-21.) and depletion of faculty vitality (Drucker-Godard, 2015Drucker-Godard, C., Fouque, T., Gollety, M., Le Flanchec, A. (2015). Career plateauing, job satisfaction and commitment ; Lee, 1995Lee, Sang-Hie (1995). “Departmental Conditions and Music Faculty Vitality.” University of Michigan, 1995. Advisor: Marvin W. Peterson. Ann Arbor, Michigan: ProQuest. Pub# 9527679 ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT), Full Text). Further, as higher education continues to lose financial support to hire additional faculty (especially in music schools), the burdens will continue to fall on these faculty members, and institutions will need to identify cost effective ways to enhance the work conditions of faculty.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the role of job crafting as a potential organizational tool that could increase faculty vitality and success. Specifically, we analyzed data from the Music Faculty Questionnaire: Faculty Vitality and Organizational Conditions to synthesize the prevalence of job crafting and how faculty perceived job crafting activities in connection to their vitality and success. We first analyzed the time spent by music faculty members in comparison to their level of commitment in order to see how faculty build their day-to-day work around their personal commitment. We then investigated how music faculty engaged job crafting to enhance revitalization and increase success by analyzing qualitative responses to two specific questions posited in the survey.

Background

Artist-professors come to universities as a means to pursue artistry in a relatively stable economic environment (Isbell, 2008Isbell, D.S. (2008). Musicians and teachers: The socialization and occupational identity of preservice music teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 56(2), 162-178.; Risenhoover, 1972Risenhoover, Morris (1972). Artist-Teachers in Universities: Studies in Role Integration. Ph.D. Dissertation. The University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI.). In addition, they gain the status and prestige that comes with being a professor and associating with a college or university. Barlar (1983) found that the majority of music faculty are motivated by the feeling of achievement, recognition for achievement, interesting work, increased responsibility, advancement, and possibility for professional growth. Similarly, Lee’s national study (1995) of ranked music professors found that work conditions that provided professional development and other support enhanced faculty vitality and was associated with higher levels of commitment to research, service, and teaching.

While music executives value teaching as the most salient in their evaluation (Hipp, 1983Hipp, William (1983). Evaluating Music Faculty. Princeton, N.J.: Prestige Publications. ; Shirks & Runnels, 1992Shirk, J.D. & Runnels, Brain D. (1992). Policies and Procedures in Music Faculty Recognition Decisions in NASM Region 9 Institutions. Proceedings: The 67th Annual Meeting of the National Association of Schools of Music, Number 80. Orlando, Florida, November 23-27, 123-144.), faculty were mixed in their levels of commitment to the three main roles of faculty work (i.e., teaching, service, and research). LeBlanc and McCrary (1990) found that academic music faculty (i.e., music theory, music history, music education, and music therapy) are motivated primarily by intellectual curiosity, enjoyment, self-improvement, and perceived duty. In a study with 14-item Music Education Workload Questionnaire (MEWQ), Chandler and Russell (2012) learned that music education workload involved 74% teaching, 14% research, and 12% service. Contrarily, the respondents expressed the ideal workload to be 63% teaching, 22% research, and 15% service. While there was no significant difference between tenured and tenure-track music education faculty, past research illustrates a disconnect between faculty, and academic leaders, expectations and reality.

In connection with how faculty allocate their time, scholars have long been interested in the level of engagement, or vitality, of faculty (Baldwin, 1985Baldwin, R. (1985), editor. Incentives for Faculty Vitality. San Francisco: Josey-Bass.; Clark & Corcoran, 1985Clark, S.M. & Corcoran, M.E. (1985). Individual and organizational contributions tofaculty vitality: An institutional case study. In S. Clark & D. Lewis (Eds.). Facultyvitality and institutional productivity: Critical perspective for higher education (112-138). New York: Teachers College, Columbia University Press.; Baldwin, 1990Baldwin, R. (1990). Faculty vitality beyond the research university: Extending a conceptual). Lee (1995) specifically sought to understand what led to higher levels of vitality in her study, identifying work conditions and personal attributes as potential precursors to music faculty vitality, engagement, and satisfaction. However, since the late 90’s, vitality scholars have shifted their attention to vitality issues concerning aging faculty (Bland & Bergquist, 1997Bland, C.J. & Bergquist, W.H. (1997). The Vitality of Senior Faculty Members. Snow on the Roof-Fire in the Furnace. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, Vol. 25, No. 7. (ED415734).; Huston, Norman, & Ambrose, 2007Huston, T.A., Norman, M., Ambrose, S.A. Expanding the Discussion of Faculty Vitality to Include Productive but Disengaged Senior Faculty. The Journal of Higher Education, 9/1/2007, Vol. 78, Issue 5, p. 493-522.), mid-career faculty development (West, 2012West, E.L (2012). What are you doing the rest of your life? strategies for vitality and fostering faculty development mid-career. Journal of Learning in Higher Education, Spring 2012, Vol. 8 Issue 1, p 59-66, 8p, Database: Education Source.), and health faculties in the context of job satisfaction, culture, climate, and gender (e.g., Ash et al., 2004Ash, A. S., Goldstein, R., & Friedman, R. H. (2004). Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: Is there equity? Annals of Internal Medicine, 14(3), 205-212.; Bunton, 2008Bunton, S.A. (2008). Differences in U.S. medical school faculty job satisfaction by gender. Analysis in Brief, 8(5), 1-2. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges. ; Palmer et al., 2010Palmer, M.M., Dankoski, M.E., Smith, J.S., Brutkiewicz, R.R., & Bogdewic, S.P. (2011). Exploring Changes in Culture and Vitality: The Outcomes of Faculty Development. The Journal of Faculty Development, Volume 25, 1, 21-27.; Pololi, et al., 2015Pololi, L.H., Evans, A.T., Civian, J.T., Gibbs, B.K., Coplit, L.D., Gillum, L.H., Brennan, R.T. (2015). Faculty Vitality-Surviving the Challenges Facing Academic Health Centers: A National Survey of Medical Faculty. Academic Medicine; Jul2015, Vol. 90 Issue 7, p 930-936.). Regardless of disciplinary fields, it has been determined that organizations have power to hinder, or enhance, the vitality and engagement of their faculty.

As has been seen, the multiple roles of music faculty provide a complex picture for which there is little information. The purpose of this study is to apply the conceptual framework of job crafting and examine how music faculty engage in active job crafting to revitalize their work commitment and enhance success. This information provides critical insights on how music executives may initiate the recently developed job-crafting model with their faculty (Timms et al., 2012Footnote text).

Conceptual Framework

Wrzesniewski & Dutton (2001) introduced the concept of job crafting after investigating individuals in traditionally boring or undesirable jobs to understand how they found meaning in their work. They proposed that these employees were acting as ‘job crafters’ and would shape their tasks and interactions in ways that brought the greatest satisfaction into their work and that “such actions affect both meaning of the work and one’s own identity” (p. 180). Timms and colleagues (2012) further defined job crafting as “the self-initiated changes that employees make in their own job demands and job resources to attain and/or optimize their personal (work) goals” (p.173). In short, job crafting occurs when employees are offered some flexibility in a structure that is also willing to accommodate individuals’ meaning and preferences (Berg et al., 2013Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B.J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.). An example of job crafting in this light might include altering the scope and type of the tasks being performed and changing the quality and amount of time spent on the tasks.

Researchers have found that job crafting is associated with higher levels of employee satisfaction, engagement, and innovation (Berg et al., 2013Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B.J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.). These positive results in turn lead to positive organizational outcomes such as lower turnover, new ideas, and efficiency (Timms et al., 2012Timms, M., Bakker, A.B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting).

This mutual symbiosis is explored in this study relative to music professors’ roles. Faculty members are ideal candidates for job crafting as they are given a wide variety of tasks within their work, as they traditionally enjoy the autonomy to conduct research and creative activities of their choice, and they have the potential to express job crafting flexibility in their teaching and service roles as well.

Methodology

Data

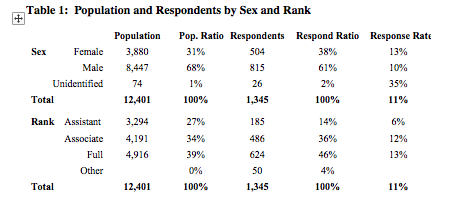

This study utilized data collected from the distribution of a survey questionnaire to the entire population of ranked professors listed in the CMS registry.1 We limited our population to tenured and tenure-track faculty members with a rank of assistant professor or higher. This was due to the limited faculty role (e.g., teaching only or administrative role only) of instructors, lecturers, and part-time adjunct artist-professors who serve the institution, but are not necessarily required to participate in the shared governance responsibility. Of the 12,401 surveys distributed, we received 1,345 (11%) usable responses within the designated time frame from August to September 2015. This response rate limits the generalizability of the findings but still represents a substantial portion of the entire population of music faculty.

Table 1 presents the number and percentage of our respondents when compared to the population. The largest difference between our sample and the population is that there are more advanced faculty and men in our sample. As a way to minimize this limitation, we analyzed our results by sex and academic rank so that readers can compare across groups. While the sample may be disproportionate in academic rank (i.e., oversampling of full professors and under sampling of assistant professors) and may act as a limitation, it can also provide some strength to our study regarding what has helped these more advanced faculty become revitalized.

Analytical Approach

The data was analyzed with a both quantitative and qualitative methods. First, we conducted a descriptive analysis to examine how music faculty spent their time in specific areas of their jobs within three main job roles: teaching, research, and service. We then compared time spent on job roles to the levels of commitment across select demographic groups (i.e., sex, faculty rank, years of service, administrative experience, institutional control, and institution type). This process informs how faculty craft their work in relation to the respective commitment across institutional context and professional experience.

Second, qualitative expressions of work revitalization and successful change experiences were analyzed to understand what specific activities faculty members associate with revitalization and success in their work. The categorization of the responses was guided in part by the job crafting framework. The qualitative analysis provided information on both work-related actions and personal shifts perceived by respondents to enhance their energy and work success.

Results

Prior to analyzing job crafting, faculty perceptions of their work conditions connected to job crafting were analyzed. The result highlights four work conditions valued by music faculty that promote active job crafting: (1) freedom to conduct own research and creative-artistic performance (mean=4.37, SD=.98), (2) performing untested repertoire (mean=4.16, SD=1.00), (3) research in uncharted fields (mean=3.88, SD=1.00), and (4) willingness to explore new career in music (mean=3.20, SD=1.22). The relatively high scores of these factors (with the exception of willingness to explore new career in music) indicate that music faculty are enjoying a fair amount of autonomy and are able to craft their work. While interesting to note the value faculty put on these work conditions associated with job crafting, a descriptive analysis of time spent on roles and the in-depth examination of qualitative data on renewal and change experiences, provides for a rich understanding of the role of job crafting and its importance to faculty vitality.

Job Crafting Descriptive Analysis

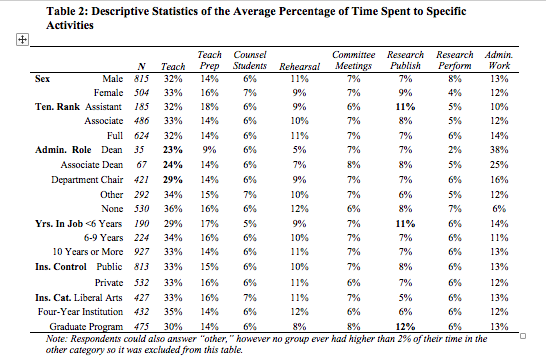

Table 2 presents music professors’ allotment of their time on their responsibilities. Professors across all groups spent similar amount of time in teaching (32-36%) and class preparation (14-18%) with exception of faculty with administrative roles. Further, the percentages of time spent on publication research by assistant professors (11%), faculty less than six years in the current job (11%), and faculty in institutions with graduate program (12%) are slightly higher in comparison to the other groups. In short, the results indicate that faculty spend similar amounts of time on their responsibilities regardless of demographic group or experience.

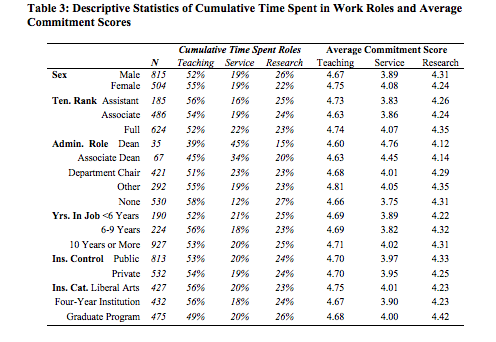

In Table 3, the average commitment score for each of the three roles and the cumulative time spent on each. On average, around 53% of music faculty time is devoted to teaching, 25% to research in its various forms (e.g., performance and publication), and 20% to service. Of note, the ratios of commitment scores for the three faculty roles—with the highest level of commitment being in teaching, followed by research, and then service—show a similar trend of the faculty time allocation. Further, the ‘other’ category is consistently low (2-3 %), indicating that the respondents’ time spent are congruent to their assigned roles.

There is a small gender difference in teaching and research. Female professors spend 55% in teaching and 22% in research, while male professors spend 52% teaching and 26% in research, denoting a 3% difference between male and female in teaching and a 4% difference in research.2 In addition, full professors devoted slightly higher percentage of time in service (22 %) than associate (19%) and assistant professors (16%)—possibly explained by the fact that organizational commitment tends to increase as professors mature in their roles.

When comparing commitment scores to the time spent on specific roles, there appears to be a corresponding relationship, with a few noteworthy exceptions. For example, as music professors progress in rank they spend less time on research, but their commitment to research increases. This may be explained by the fact that senior-level faculty may take less time to get more done due to experience in publishing, expertise in a body of literature and research protocols, access to research assistants, or the availability of accumulated datasets.

Another noteworthy exception is that regardless of having an administrative position, the commitment to teaching score remains relatively the same for all faculty members. This is worth noting as a positive sign because it is easy for the administrative faculty to neglect the importance of teaching commitment. Aside from these few anomalies, Table 3 presents a strong correspondence between time spent on a role and the faculty members’ commitment to that role, possibly indicating that faculty are crafting their work based on their level of commitment.

Job Crafting Qualitative Analysis

Following analysis of where faculty spend their time, an examination of qualitative responses to two questions addressing was conducted to see how faculty are able to reenergize their work: (1) renewal, ‘If you experienced a revitalization of your work productivity, how did you renew your vitality?’ and (2) increased success, ‘To what extent did any of the following changes have to increase your success as a faculty member?’ There were 860 responses to the first question and 269 to the second.

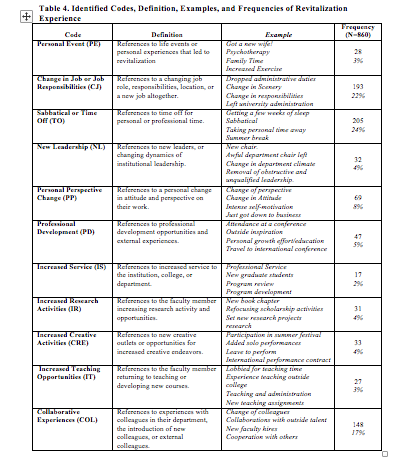

Renewal. Table 4 presents the identified codes of the responses on renewal. Change of job or job responsibilities was coded 22%, sabbatical or time off, 24%, and collaborative experiences, 17%.

In addition, faculty experiences in renewal, through the opportunity to engage in research (4%), creative activities (4%), professional development (3%), teaching (3%), and increased role in service (2%), account for 15% of the responses when combined. This demonstrates the many different modes through which faculty craft their work in the revitalization process. Of note, there are a few responses that are vague. For example, some respondents stated ‘new responsibilities’ within the change of job category, in which case, it is unclear whether this may be a change-job category or changed amount of responsibilities in teaching, research, and service.

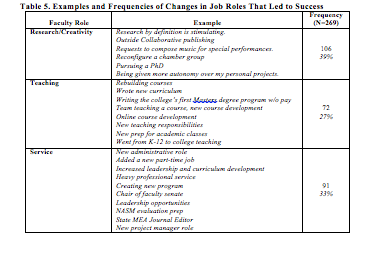

Increased success. Table 5 presents examples and frequencies on how a change in job led to job success inclusive of teaching, research, and service opportunities. The majority of responses identified changes in research (39%) that led to success in faculty work. Primarily, professors stated that opportunities to publish collaboratively, reconfigure a performance group, or increased autonomy over their personal projects led to increased success.

Respondents also commented on the importance of renewed teaching, especially, rebuilding courses, writing curriculum for a master’s program, and online course development to be very important in effecting revitalization. Similarly, respondents who connected service to increased success identified service in professional organizations and administrative roles in their department as significant activities. Thus, the qualitative responses provide more detailed insights into how active job crafting contributes to faculty revitalization and success brought by the changes that faculty make. Interestingly, respondents not only discussed answers to the question about specific experiences, but introduced crafting language that could help them to enhance their vitality. For example, “I prioritized my work,” or “I decided I would reach out to additional colleagues.” These statements indicated that these faculty took initiatives in crafting their environment.

Discussion

Understanding how to strengthen and support faculty is critical to the success of higher education institutions as faculty are the life blood of institutional success. As such, this study introduced the concept of job crafting by analyzing how music faculty are crafting their work within the structural limitation of time spent to their area of commitment and identifying aspects of job crafting that are associated with revitalization and successful changes. The results suggest that job crafting is a significant avenue for revitalization and increased successful changes. We discuss five notable findings from the analysis and their subsequent implications for music faculty and academic leaders.

First, our findings on how faculty spend their time is somewhat different than past research (Chandler & Russell, 2012Chandler, K.W. & Russell, J. (2012). A comparison of contracted and ideal music education faculty workload. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 193, 77-89.). We find that faculty have a more balanced time spent on teaching (54%), research (26%), and service (20%). Further, our results indicate that commitment levels are strongly associated with faculty time spent in the respective role and in job crafting. This demonstrates that faculty are already engaged in active job crafting by spending time in the areas they are committed too.

Second, as faculty engage in job crafting, we find that 22% of faculty view changing their job roles as a precursor to revitalization. This demonstrates that faculty view shifting responsibilities to be important to rejuvenate their work. Many of these responses discussed shifting from administrative roles back to teaching and research roles. Another common idea for job change was to spend more time on research. This implies that academic leaders need to be cognizant of the amount of time music faculty are asked to serve in administrative positions. A heathy change of duties decided by the faculty could lead to higher vitality.

The third finding of note is that faculty viewed the collaboration with colleagues as reinvigorating (18%). The responses categorized here referenced meeting new colleagues, engaging in research projects with new collaborators, and connecting with individuals outside of their college. This is another example of a low-cost way to enhance the vitality of their faculty. Further, music faculty can seek to build more robust social support networks that can help them to find higher levels of engagement.

Fourth, 18% of respondents felt revitalized by simply increasing their involvement in one of the main faculty responsibilities of research, teaching, service, or creativity. This shows evidence that simply providing autonomy for faculty to craft their work can be a great institutional tool. Administrators and faculty alike can pursue ways to be engaged in active crafting within their roles by a new course development or new research project.

Finally, our results of what led to greater levels of success underscore the importance of balance between research/creativity, teaching, and service. Administrators can help to facilitate balance of incentives for the three main job roles.

It is clear from the data that job crafting is happening, and more importantly it has a positive impact on music faculty members’ revitalization and enhanced success. Specifically, the data show that music faculty enjoy a high level of freedom to conduct their own research and creative performance, and they allocate time parallel to the three areas of responsibilities. This active participation in crafting balanced job roles is an advantage that workers outside of the academy may not entertain.

Summary and Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of providing opportunities for faculty members to craft their work, so that they may be able to choose not only the amount of time spent in different role tasks but also to recast job boundaries and change the quality of interactions. Job crafting, “the self-initiated changes that employees make in their own job demands and job resources to attain and/or optimize their personal (work) goals” (Timms et al’s, 2012, p.173Timms, M., Bakker, A.B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173-186.), has been found to have an important effect on job satisfaction, revitalization, and success. For music faculty, it appears to have similar effect to revitalize and lead to increased success.

Job crafting gives professors an understanding of how work conditions and intrinsic perspectives are inherently associated not only with their three main work roles but also directly to the organizational commitment in affective (this refers to an emotional attachment to the organization as result of sharing similar goals and values with the organizations) and normative (this stems from a feeling of obligation that arises from loyalty to an organization as illustrated by the attachment to an alma mater or sports team) ways (Wiener, 1982Wiener, Y. (1982). Commitment in organizations: A normative view. Academy of management review, 7(3), 418-428.).

This study suggests that administrators in higher education institutions can develop stronger support structures for job crafting, better understanding of the artistic and creative job crafting of music faculty work, and better evaluation and reward systems that reinforce job crafting.

Endnotes

The CMS is a national society of music professors who teach in colleges, conservatories, universities, and community colleges throughout the United States and Canada. The mission of the Society is to promote “music teaching and learning, musical creativity and expression, research and dialogue, and diversity and interdisciplinary interaction” (www.music.org). The CMS faculty registry includes the entire national music faculty. We found a few discipline-specific faculty studies that examined gender differences among medical faculty. For example, Bunton (2008) found that 68% of men and 60% of women respondents reported being satisfied with their “fit” in the department, p<.001; 39% of the men vs. 33% of the women, p<.001 responded positively about the supportive climate; and 60%, men vs. 55%, women p<.01 agreed that the workplace culture cultivated collegiality. Other medical faculty studies show that while 50% of medical students today are female, significant gender difference remains in promotion, compensation, and perception of climate (Ash et al., 2004Ash, A. S., Goldstein, R., & Friedman, R. H. (2004). Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: Is there equity? Annals of Internal Medicine, 14(3), 205-212.) with only 18% representing full professors, 13% departmental chairs, and 12% medical school deans (Palmer et al., 2011Palmer, M.M., Dankoski, M.E., Smith, J.S., Brutkiewicz, R.R., & Bogdewic, S.P. (2011). Exploring Changes in Culture and Vitality: The Outcomes of Faculty Development. The Journal of Faculty Development, Volume 25, 1, 21-27.).

References

Ash, A. S., Goldstein, R., & Friedman, R. H. (2004). Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: Is there equity? Annals of Internal Medicine, 14(3), 205-212.

Baldwin, R. (1985), editor. Incentives for Faculty Vitality. San Francisco: Josey-Bass.

Baldwin, R. (1990). Faculty vitality beyond the research university: Extending a conceptual

Context. The Journal of Higher Education, Vol 61, Issue 2, p. 160-180.

Barlar, D. (1983). Source of motivation among college music faculty. (Unpublished Doctoral

dissertation). George Peabody College for Teachers of Vanderbilt University.

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B.J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bernhard, H.C.II (2007). A survey of burnout among university music faculty. College Music Symposium, Vol. 47, pp.117-126.

Bland, C.J. & Bergquist, W.H. (1997). The Vitality of Senior Faculty Members. Snow on the Roof-Fire in the Furnace. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, Vol. 25, No. 7. (ED415734).

Bunton, S.A. (2008). Differences in U.S. medical school faculty job satisfaction by gender. Analysis in Brief, 8(5), 1-2. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges.

Chandler, K.W. & Russell, J. (2012). A comparison of contracted and ideal music education

faculty workload. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 193, 77-89.

Clark, S.M. & Corcoran, M.E. (1985). Individual and organizational contributions to

faculty vitality: An institutional case study. In S. Clark & D. Lewis (Eds.). Faculty

vitality and institutional productivity: Critical perspective for higher education (112-138). New York: Teachers College, Columbia University Press.

Corcoran, M.E. & Clark, S.M. (1984). Professional socialization and contemporary career

attitudes of three faculty generations. Research in Higher Education, 20 (2), 131-153.

Drucker-Godard, C., Fouque, T., Gollety, M., Le Flanchec, A. (2015). Career plateauing, job

satisfaction and commitment of scholars in French universities. Public Organization Review, 15 (3), 335-351. Sept, 2015.

Hamann, Donald L., Daugherty, Elza, and Sherbon, James (1988). Burnout and the College Music Professor: An Investigation of Possible Indicators of Burnout Among College Music Faculty Members. Council for Research in Music Education. Bulletin No. 98. Fall, 1-21.

Harris, Rod D. (1991). Musician and Teacher: The Relationship Between Role Identification and Intrinsic Career Satisfaction of the Music Faculty at Doctoral Granting Institutions. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. University of North Texas.

Hipp, William (1983). Evaluating Music Faculty. Princeton, N.J.: Prestige Publications.

Huston, T.A., Norman, M., Ambrose, S.A. Expanding the Discussion of Faculty Vitality to Include Productive but Disengaged Senior Faculty. The Journal of Higher Education, 9/1/2007, Vol. 78, Issue 5, p. 493-522.

Isbell, D.S. (2008). Musicians and teachers: The socialization and occupational identity of preservice music teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 56(2), 162-178.

LeBlanc, A. and McCrary, J. (1990). Motivation and perceived rewards for research by music

faculty. Journal of Research in Music Education, 35(1), 61-68.

Lee, Sang-Hie (1995). “Departmental Conditions and Music Faculty Vitality.” University of Michigan, 1995. Advisor: Marvin W. Peterson. Ann Arbor, Michigan: ProQuest. Pub# 9527679 ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT), Full Text

Lee, Sang-Hie (1995). Music Faculty Questionnaire: Music faculty Vitality and Organizational Conditions. Washington DC: Library of Congress.

Palmer, M.M., Dankoski, M.E., Smith, J.S., Brutkiewicz, R.R., & Bogdewic, S.P. (2011). Exploring Changes in Culture and Vitality: The Outcomes of Faculty Development. The Journal of Faculty Development, Volume 25, 1, 21-27.

Pololi, L.H., Evans, A.T., Civian, J.T., Gibbs, B.K., Coplit, L.D., Gillum, L.H., Brennan, R.T. (2015). Faculty Vitality-Surviving the Challenges Facing Academic Health Centers: A National Survey of Medical Faculty. Academic Medicine; Jul2015, Vol. 90 Issue 7, p 930-936.

Rees, Mary Anne (1984). University Music Faculty: Work Attitudes, Recognition, and Satisfaction. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Oregon. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI.

Risenhoover, Morris (1972). Artist-Teachers in Universities: Studies in Role Integration. Ph.D. Dissertation. The University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI.

Ritenbaugh, Thomas David (1989). Artist, Teacher, Scholar, Organizational Leader, Administrator, Collector: Art Educators' Beliefs About Roles and Status. Ph.D. Dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University. Dissertation Abstracts International, 51-02A, 388.

Shirk, J.D. & Runnels, Brain D. (1992). Policies and Procedures in Music Faculty Recognition Decisions in NASM Region 9 Institutions. Proceedings: The 67th Annual Meeting of the National Association of Schools of Music, Number 80. Orlando, Florida, November 23-27, 123-144.

Taylor, Jack (2014). Letter from CMS Committee Chair to communicate CMS endorsement of the survey instrument, Music Faculty Questionnaire: Faculty Vitality and Organizational Conditions. Email correspondence dated January 17, 2014.

Timms, M., Bakker, A.B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting

scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173-186.

West, E.L (2012). What are you doing the rest of your life? strategies for vitality and fostering faculty development mid-career. Journal of Learning in Higher Education, Spring 2012, Vol. 8 Issue 1, p 59-66, 8p, Database: Education Source.

Wiener, Y. (1982). Commitment in organizations: A normative view. Academy of management

review, 7(3), 418-428.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J.E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active

crafters of their work. Academy of management review, 26(2), 179-201.