As philosopher John Dewey has noted:

"The moral function of art itself is to remove prejudice, do away with the scales that keep the eye from seeing, tear away the veils due to wont and custom, perfect the power to perceive. The critic's office is to further this work, performed by the object of art."1Dewey, Art as Experience, 325.

Following Dewey, I have come to believe that one of the most important functions of art is to re-connect us to the world; specifically, with respect to music, to re-sensitize us to its unfathomably rich sonic universe. Every aspect of our daily lives seems to create barriers to this re-connection. Those composers who seem most interesting to me are the ones who try to break through these barriers.

Few contemporary composers have been more dedicated to this goal than Giacinto Scelsi (1905-88). For an excellent general introduction to Scelsi’s music and philosophy I would recommend the book Music as a Dream: Essays on Giacinto Scelsi, edited by Franco Sciannameo and Alessandra Carlotta Pellegrini, the best collection of essays on Scelsi in English at present.2Sciannameo and Pellegrini eds., Music as a Dream: Essays on Giacinto Scelsi. Scelsi was one of the leading Italian experimental composers of the 20th century. He studied with Giacinto Sallustio in Italy and Walter Klein, a pupil of Arnold Schoenberg, in Vienna. From these teachers he learned of the latest developments in composition in the early decades of the century. However, it was not until after World War II that his unique compositional voice began to emerge. At this time he began an intense, life-long study of Eastern philosophies which led him to reconsider his basic conception of musical composition. He emphasized improvisation over pre-compositional planning. This, in turn, led to a new creative focus on the nature of sound itself, treating each individual sound as a complex acoustical phenomenon, and a rich compositional resource. Furthermore, his conception of musical form changed; the design of each new composition emerged from an exploration of the acoustical properties of each sound employed, both in terms of how it is produced, as well as how it is perceived.

Certainly, in this endeavor Scelsi had predecessors. One whose views, if not necessarily his music, deeply influence him was Dane Rudhyar, perhaps today the least know of early 20th Century experimental composers working in the United States.3For an excellent introduction to Rudhyar’s work see Ertan, Dane Rudhyar: His Music, Thought, and Art. Scelsi and Rudhyar shared an understanding of the importance of resonance and the overtone spectrum to our perception of sound and out experience of music, no matter the historical period or culture of origin. Gregory Reish has noted that:

In books published in 1928 and 1930 Rudhyar discussed at length the untapped potential of the single note, giving particular emphasis to the pleroma of sound, a saturation of the sonic spectrum he defined as “fullness of conjoined tones within certain limits,” from which a tiny portion might be carved out in the act of artistic creation [my italics].4Reish, “Una Nota Sola: Giacinto Scelsi and the Genesis of Music on a Single Note.” 152. The books by Rudhyar referenced in this citation are The Rebirth of Hindu Music and Art as Release of Power: A Series of Seven Essays on the Philosophy of Art.

As we will see, these comments are particularly significant in light of the subsequent analysis of Scelsi’s work in this paper. While Rudhyar’s own music never really achieved his lofty goals, his ideas made a lasting impression on Scelsi and inspired Scelsi to proceed along his creative path.

From the 1950’s onward Scelsi treated each composition as an opportunity to reveal to a listener the inherent complexity of even the most seemingly simple of sounds – a single, sustained pitch. One of his most famous compositions, and the first piece written in this new style to achieve widespread acclaim, was his Quattro Pezzi (su una nota sola) (1959), four pieces for orchestra, each of which is based upon a single note. Each of the four pieces in this work is built upon one primary tone which is colored in a variety of ways, using the various timbres and textures available through a symphony orchestra. In each of these pieces he puts one tone under a microscope revealing its teeming inner life, rendering audible all the fluctuating overtones, attack noise and pitch deviations that lie beneath its surface. However, in my view this approach to composition achieved its purest form and highest level of sophistication in his music for strings written between the 1960’s and ’80’s, in works such as Xnoybis, for violin (1964), Arc-en-ciel, for two violins (1973) and his fourth and fifth string quartets (1964 and 1984 respectively). Through each of these mature works Scelsi revealed the inner life of each sound he employed, the many components of which shape our perceptions. After hearing a work by Scelsi one feels as though, for the first time, one has experienced the extraordinary richness of the sounds we encounter every day. In thinking about his work one is immediately reminded of Schenker’s concept of the composing out of a fundamental sonority: in Schenker’s case, of course, I refer to what he calls the “chord of nature,” in Scelsi’s case I refer to any sound.5In Schenker’s view the so-called “chord of nature” – a concept not original to Schenker alone – is derived from the first five overtones of a fundamental frequency, which together constitute the tones of a major triad. Schenker saw this chord, and its expansions, as the source of tonal composition.

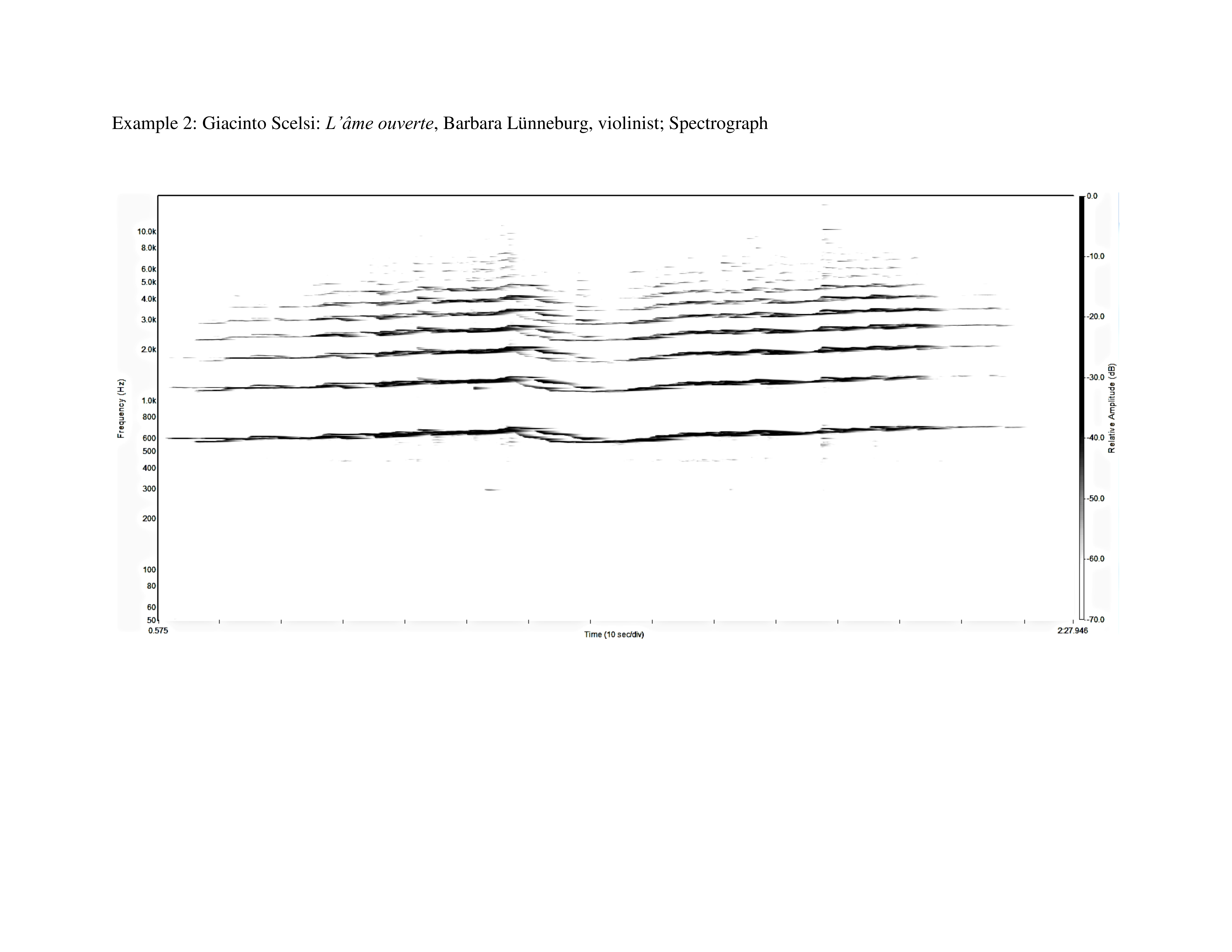

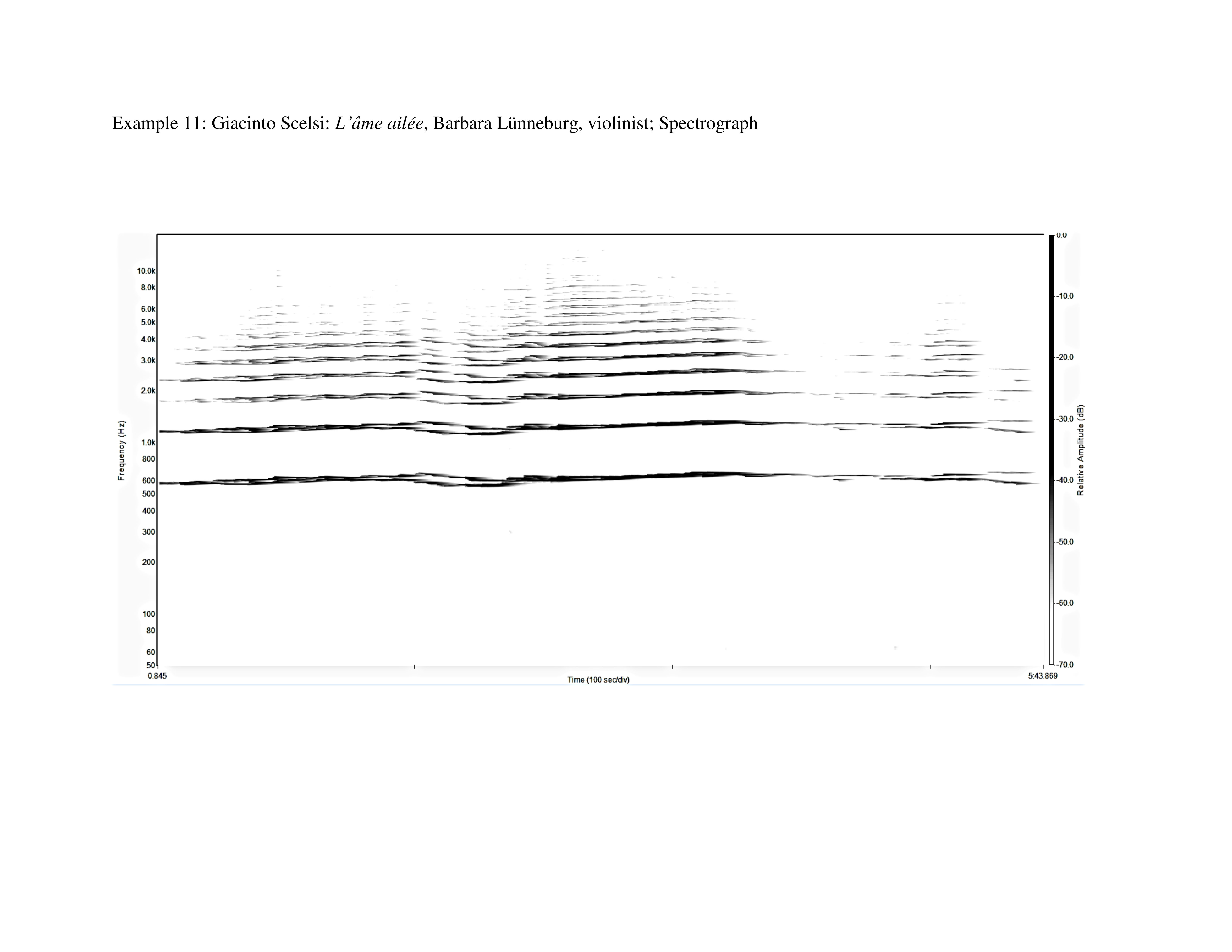

In order to fully understand the complexity of Scelsi achievement we require new analytical tools. The most useful are spectrographs, which afford the means to study sound in all its dimensions.6The most comprehensive use of spectrographs in the study of music is found in the work of theorist Robert Cogan, whose book New Images of Musical Sound represents a landmark in the development of this type of analysis, using musical examples drawn from a variety of eras and cultures. They reveal to us not only the time varying nature of the overtone spectra of apparently unchanging sustained sounds, but also the microscopic fluctuations and bifurcations of pitch which are inherent in such sounds. These factors, of course, are essential to understanding what we actually hear. The use of spectrographs has become more prevalent today among theorists and musicologists who are concerned with examining our listening experience – what we are actually hearing when we listen to a piece of music, not just what is notated in a score, which, after all, is just a guide for performance, not a representation of a sonic event. On the following spectrographs the x-axis represents time and the y-axis represents frequency. The darker shading of any line represents a louder sound, lighter shading, a softer sound.

Not only is the fundamental frequency (notated pitch) of a tone represented on the graphs but all its overtones as well. In addition, the time-varying amplitudes of these elements are also visible. Finally, a close examination of just the attack noise (attack transients) of a tone can show, in remarkable detail, the complex nature of this all important aspect of sound production and its importance in our experience of sound. Indeed, according to Murray Campbell and Clive Greated:

Many experiments have demonstrated, however, that the transient features which occur when a musical instrument is first set into vibration play a crucial role in providing the brain with clues to help the identification of the instrument...7Campbell and Greated, The Musician’s Guide to Acoustics, 142.

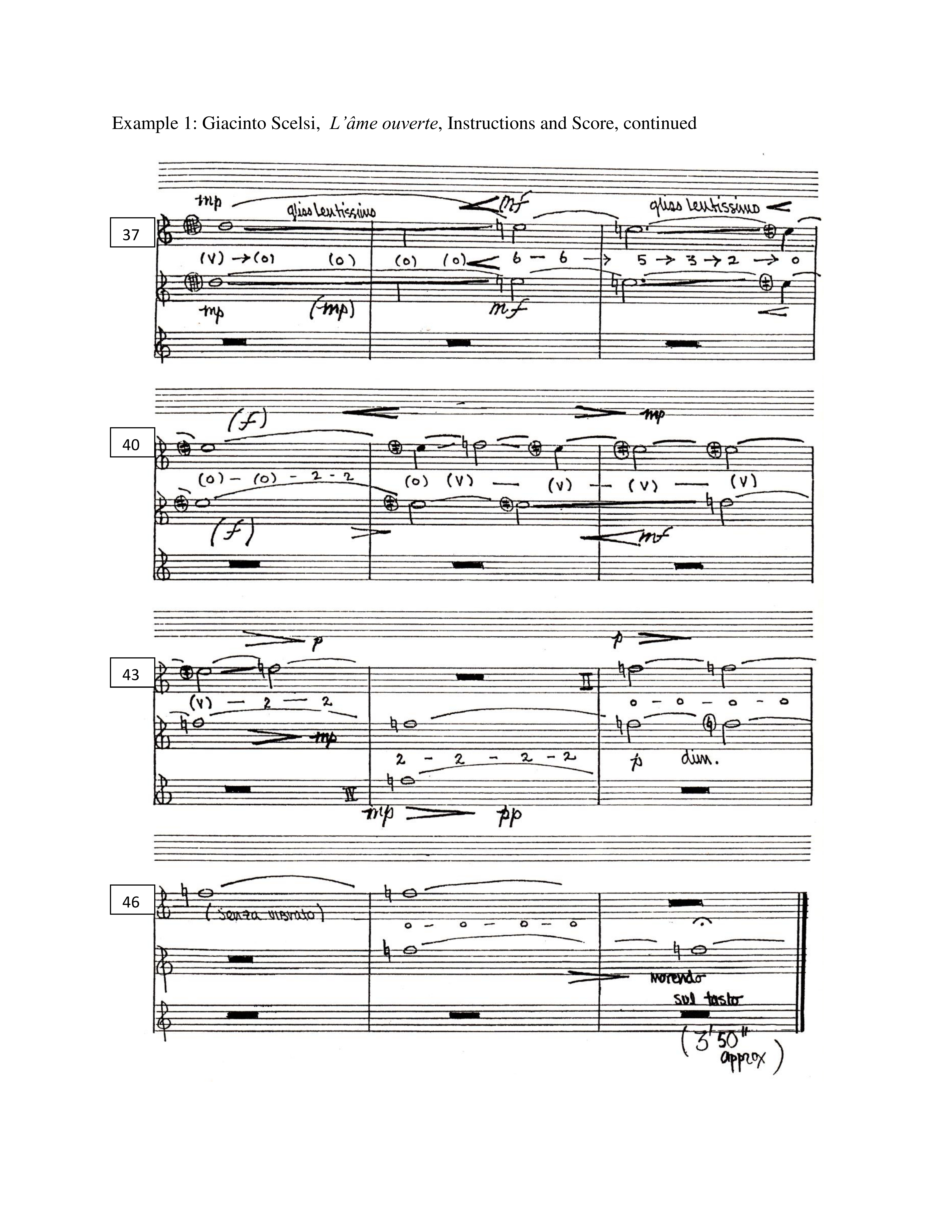

The work under consideration here is a late composition, entirely representative of Scelsi’s mature work. L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte (1973) consists of two brief, related compositions for solo violin (Example 1).8Scelsi, L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte. L’âme ailée (literally winged soul) is approximately 4’ 30” long; L’âme ouverte (open soul) is somewhat shorter, approximately 3’ 50”. I will focus upon the second of the pair and then later briefly comment upon the relationship between the two.

L’âme ouverte constitutes a single ascent from D5 to F5, a minor third, clearly visible in a spectrograph of a performance of the piece (Example 2).9Spectrographs of a recorded performance of L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte appearing in Examples 2 and 11 are taken from a performance by Barbara Lüneburg, violin, on the CD Beyond: Bach, Scelsi. Other performers have recorded the work: Weiping Lee, Giacinto Scelsi: The Violin Works; and Robert Zimansky, Giacinto Scelsi. However, the Lüneburg performance appears to be the most accurate. Spectrographs were created with the SpectraPLUS FFT Spectral Analysis System manufactured by Pioneer Hill Software. On the spectrographs the horizontal axis represents time and the vertical axis frequency measured in cps. The image reveals not only the motion of fundamental frequencies but that of their overtones as well. This ascent is broken up into two smaller ascents, the first up to E5 (m. 15), and the second to the final goal, F5 (m. 43). The tempo indication is quarter note = 60, or 1” per quarter. As with much of Scelsi’s late string music, each string of the instrument is assigned a separate stave in the score and the third and fourth strings are re-tuned (scordatura) (Example 1, Instructions). This allows the composer precise control over both the notation and production of the microtonal juxtapositions he creates.

L’âme ouverte constitutes a single ascent from D5 to F5, a minor third, clearly visible in a spectrograph of a performance of the piece (Example 2).9Spectrographs of a recorded performance of L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte appearing in Examples 2 and 11 are taken from a performance by Barbara Lüneburg, violin, on the CD Beyond: Bach, Scelsi. Other performers have recorded the work: Weiping Lee, Giacinto Scelsi: The Violin Works; and Robert Zimansky, Giacinto Scelsi. However, the Lüneburg performance appears to be the most accurate. Spectrographs were created with the SpectraPLUS FFT Spectral Analysis System manufactured by Pioneer Hill Software. On the spectrographs the horizontal axis represents time and the vertical axis frequency measured in cps. The image reveals not only the motion of fundamental frequencies but that of their overtones as well. This ascent is broken up into two smaller ascents, the first up to E5 (m. 15), and the second to the final goal, F5 (m. 43). The tempo indication is quarter note = 60, or 1” per quarter. As with much of Scelsi’s late string music, each string of the instrument is assigned a separate stave in the score and the third and fourth strings are re-tuned (scordatura) (Example 1, Instructions). This allows the composer precise control over both the notation and production of the microtonal juxtapositions he creates.

In addition, throughout the score, Scelsi measures the depth of the specific microtonal inflections he specifies by indicating the number of beats to be produced by the performer as he superimposes microtonally related pitches upon one another.10“In acoustics, a beat is an interference pattern between two sounds of slightly different frequencies, perceived as a periodic variation in volume whose rate is the difference of the two frequencies. When tuning instruments that can produce sustained tones, beats can be readily recognized. Tuning two tones to a unison will present a peculiar effect: when the two tones are close in pitch but not identical, the difference in frequency generates the beating. The volume varies as in a tremolo as the sounds alternately interfere constructively and destructively. As the two tones gradually approach unison, the beating slows down and may become so slow as to be imperceptible.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beat_(acoustics). In the fifth measure, for example, the composer indicates that one should hear 3 beats per quarter note duration in the first half of the bar, then two per quarter at the beginning of the second half of the bar. As the D¼#5 sounding on the D string slides down to D5, beating decreases to 0 per quarter note as indicated at the beginning of bar 6 where both the D and A strings sound a unison D5.

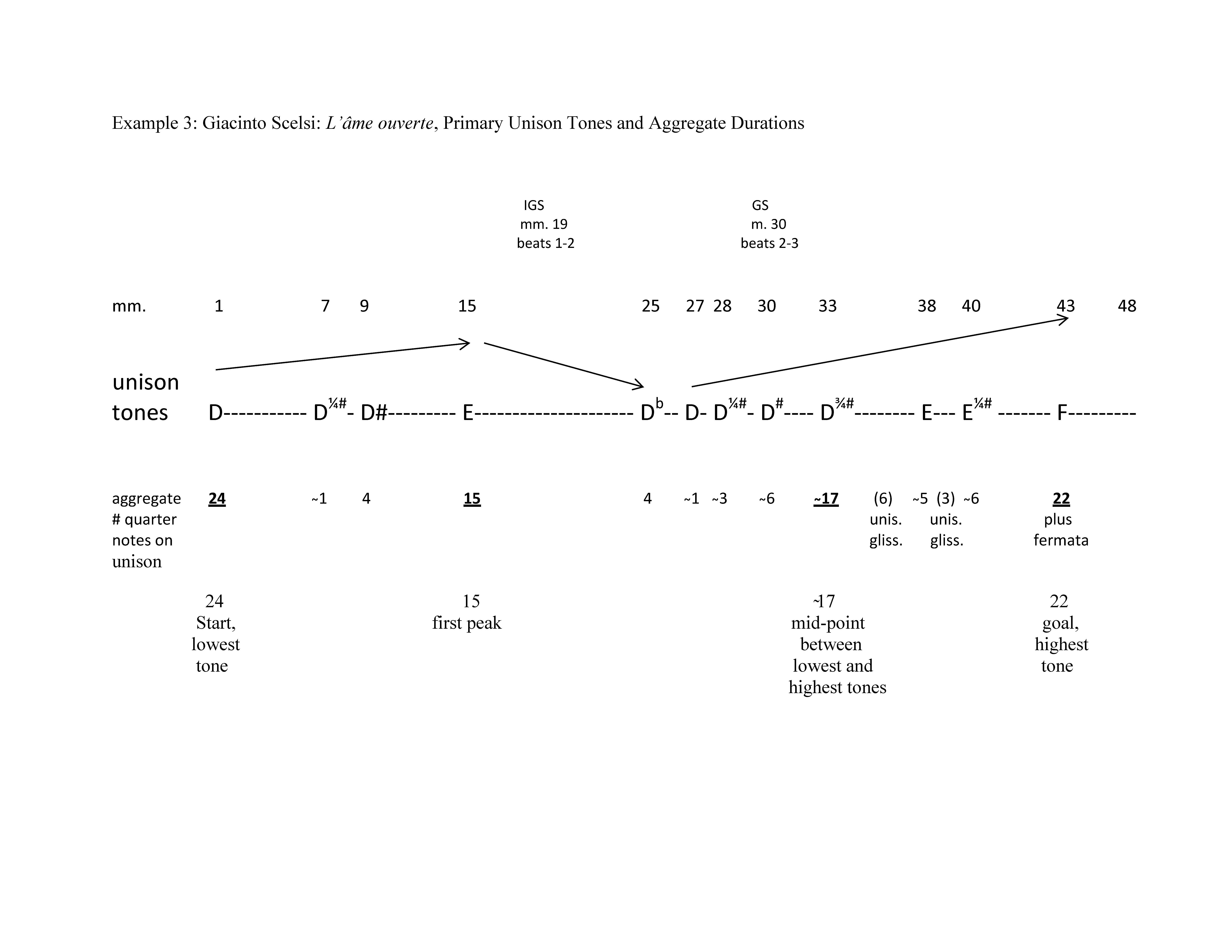

The composition moves from one such unison sonority to another as it traverses its minor third distance via similar microtonal increments. Those passages resting on a unison I will call “regions.” I have measured the duration of each such region by the aggregate number of quarter notes through which its unison tone sounds, on and off, until supplanted by another unison tone. For example:

- The composition begins on D5 (III string), sounding alone into bar 2 where a Db5 (II) enters overlapping the D5.

- This semitone continues until the end of bar 3 where the Db5 glides up to a D5, forming a unison with the first D5. This unison continues to sound until the original D5 (III) glides up to D¼#5 in bar 4.

- D5 and D¼#5 sound simultaneously until the downbeat of bar 6 at which point yet another D5 unison is heard for the entirety of that bar.

- A new unison sonority is heard, though quite briefly, in bar 7, third quarter note, where we encounter a unison D¼#5. At this point we have left the region of D5 and moved up to that of D¼#5. The composition then moves on to a third unison region, that of D#5, which begins in bar 9.

Hence, this D natural region sounds across an aggregate of approximately twenty-four quarter notes, from bar 1 through the end of bar 6 (Example 3). In contrast, the next region is quite brief. As noted above, Scelsi reaches D¼#5 unison in bar 7 on the third quarter but slides away from it immediately, a total duration of less than a quarter note (which I am calling a duration of ̴ one quarter note). He does not return to this unison again at this time but moves on to the next unison region on D#5 which stretches from the second half of bar 9 through the first half of bar 10 for a duration of four quarter notes. This unison sonority also does not return before the next is established – a unison region resting on E, starting with the unison E on the downbeat of bar 15, stretching through the third quarter of bar 18. And so the composition proceeds.

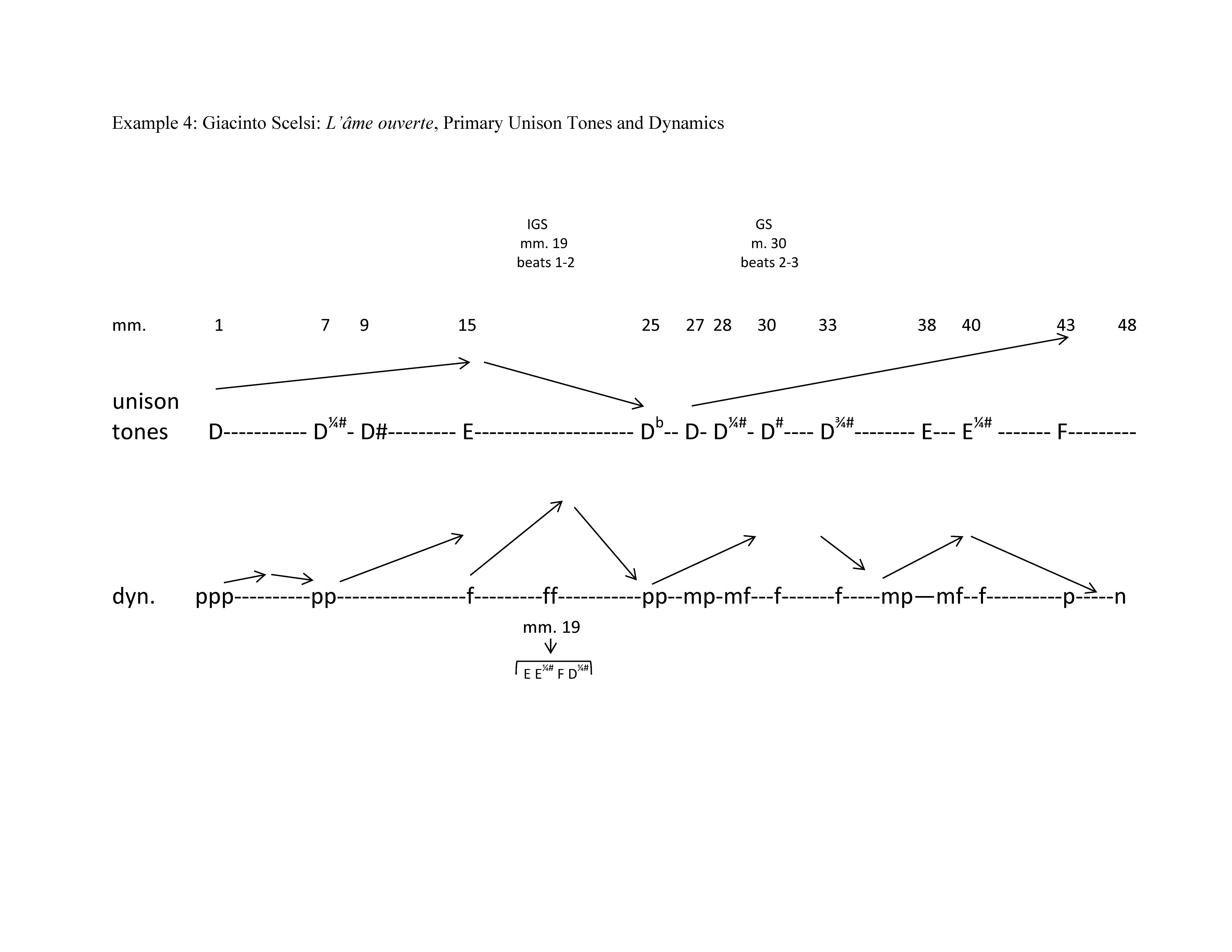

As noted, the piece constitutes two ascending motions, the first from D5 to E5 (mm. 1-15), and the second on up to F5 (mm. 15-43). Between these two ascents there is a brief drop down to Db5 (perhaps a reminder of the lowest point of the first piece in the set, C#5, as we will see). As he ascends, Scelsi rests on certain unison tones more than others: first, the initial D5, then the goal of the first ascent E5; next D¾#5 (the mid-point between D5 and F5) and finally the goal of the entire ascent F5. These specific tones are emphasized by durations far longer than any other unison sonorities (Example 3).

In terms of proportions, the Inverse Golden Mean is found between the first and second quarter notes of bar 19, precisely the center of the E5 region, which is the highest point in the first ascending motion of the work and also the loudest point in the piece, ff. In addition, since this high point is also the loudest it will project the highest partials of any point over the course of this initial ascent. As such, this will mark not only the highest notated pitch, but also the highest of all frequencies heard thus far. Similarly, the Golden Mean occurs in measure 30, between its second and third quarter-notes, coinciding with the start of the loudest passage of the second ascent of the piece, marked f. This too marks a second spectral peak, leading to the final ascent to F5. The golden mean and its inverse often mark important events in Scelsi’s music.11DeLio, “su una nota sola: Giacinto Scelsi’s Quattro pezzi, No. 3 (1959),” 325-355.

Dynamics support the two unfolding ascents of pitch through two arcs of rising and falling changes in volume (Example 4). The ascent to E5 is underscored by a crescendo from ppp (bar 1) to ff (bar 19) and then a diminuendo back to pp (bar 24). The second ascent to F5 is underscored by a crescendo from the concluding pp of the first arc (bar 24) to f (stretching from bar 30 through 36), and then a diminuendo to the end of the piece. Of course, these changes in volume generate changes in register. Upper partials become more prominent as the volume increases, as the aforementioned spectrograph of a performance of the composition clearly shows (Example 2). Thus, we experience a clear correlation between parameters throughout; fundamental pitches rise and fall, supported by corresponding changes in volume from soft to loud and back, which in turn activate ascending and descending motions across the overtone spectrum. Moreover, as noted above, these spectral peaks correspond to the proportional dimensions of the composition as determined by the Golden Mean and Inverse Golden Mean as we begin to understand the extent of Scelsi’s remarkable interlinking of parameters.

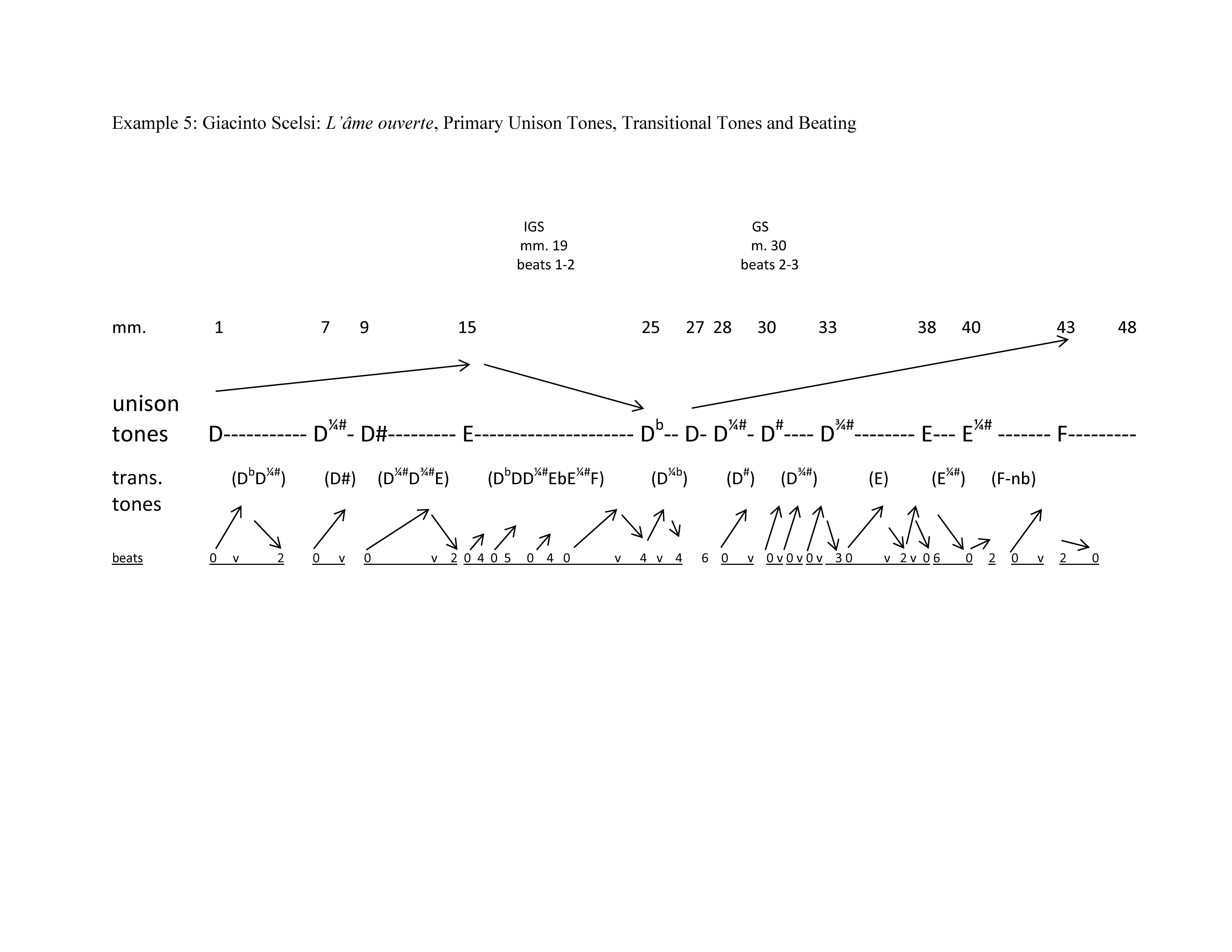

In between each of the primary pitches of the overall ascent (signified, as noted above, by moments of repose on unison sonorities) we find a succession of transitional tones, microtonal inflections of the primary (unison) tones (Example 5). These transitional tones, when sounded against the primary pitches and each other, produce beats; which, as noted, Scelsi carefully calculates and notates in his score.

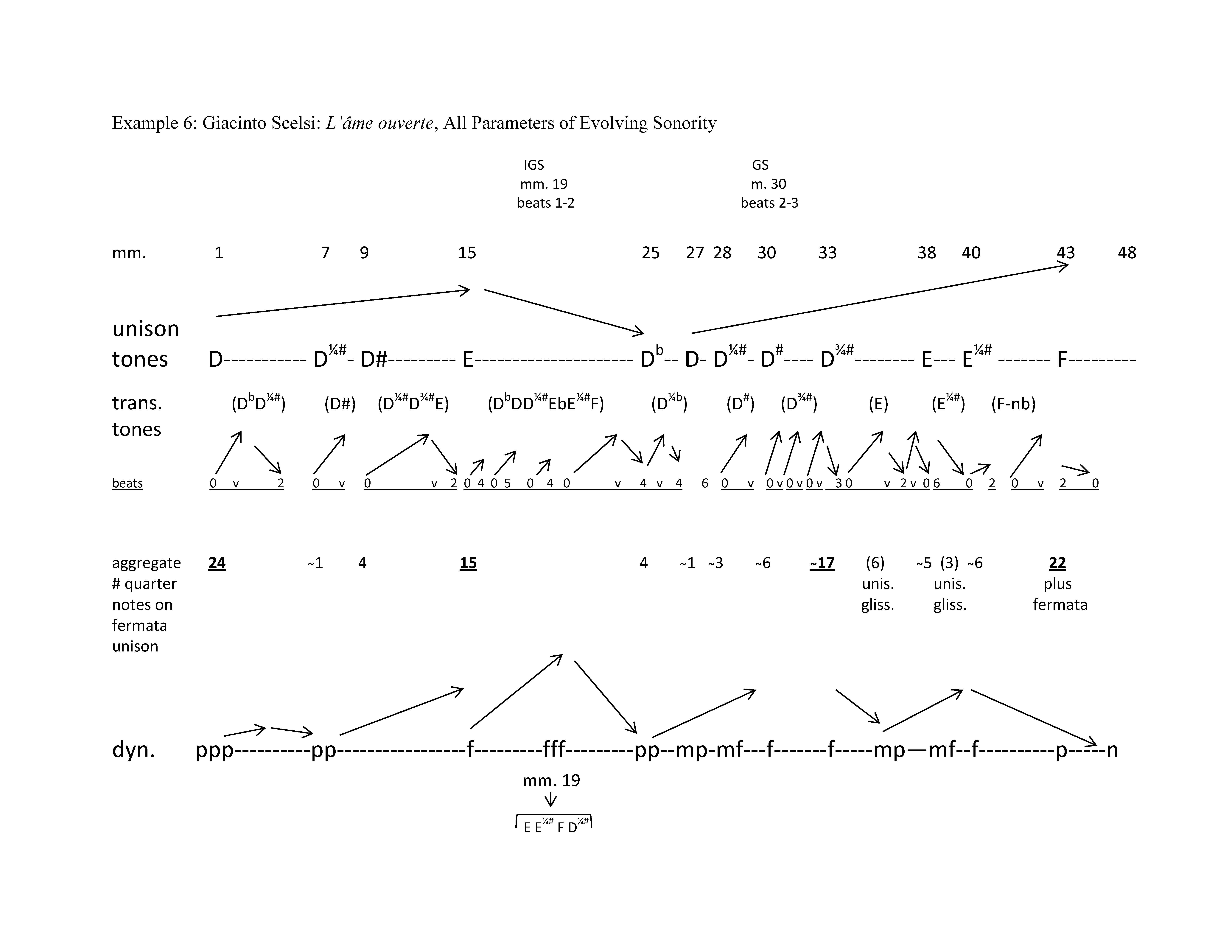

Examining his coordinated use of dynamics, microtones and beating, we grasp the full extent of Scelsi’s command of the many dimensions of our experience of sound (Example 6). In L’âme ouverte he meticulously pulls apart his unfolding sonority, coordinating the evolution of every aspect of the sound mass that emerges. Here he does indeed compose a sound, in this case, that of a violin playing the tone D5 rising to F5. If we look inside one fragment of such a sound we can see in microcosm what Scelsi has brought to the fore. In the process of creating L’âme ouverte he takes those microscopic changes that constitute the totality of our experience of a tone as played on a violin, changes of which we often may not be conscious, such as the microtonal wavering of a single note sustained on a string instrument, and magnifies them.

Examining his coordinated use of dynamics, microtones and beating, we grasp the full extent of Scelsi’s command of the many dimensions of our experience of sound (Example 6). In L’âme ouverte he meticulously pulls apart his unfolding sonority, coordinating the evolution of every aspect of the sound mass that emerges. Here he does indeed compose a sound, in this case, that of a violin playing the tone D5 rising to F5. If we look inside one fragment of such a sound we can see in microcosm what Scelsi has brought to the fore. In the process of creating L’âme ouverte he takes those microscopic changes that constitute the totality of our experience of a tone as played on a violin, changes of which we often may not be conscious, such as the microtonal wavering of a single note sustained on a string instrument, and magnifies them.

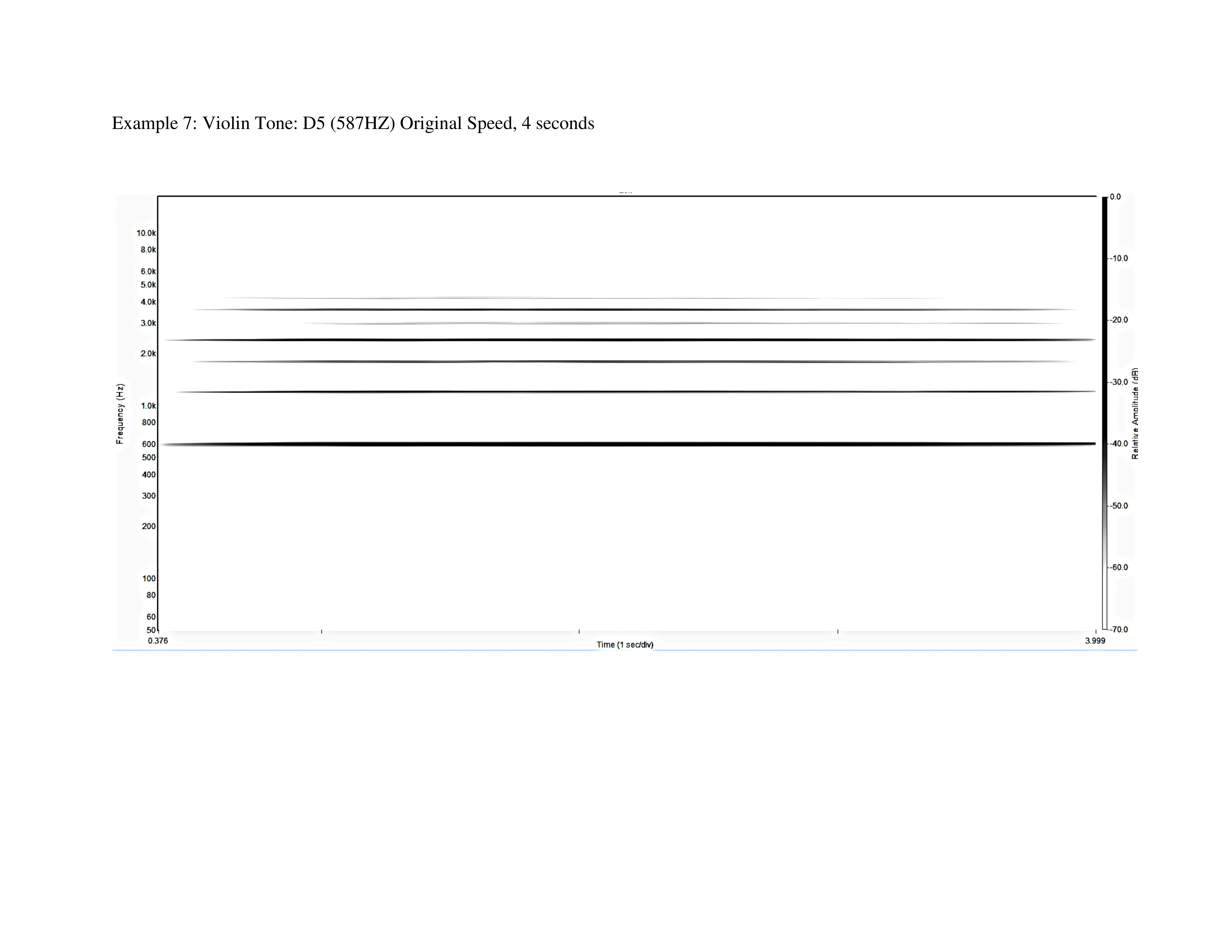

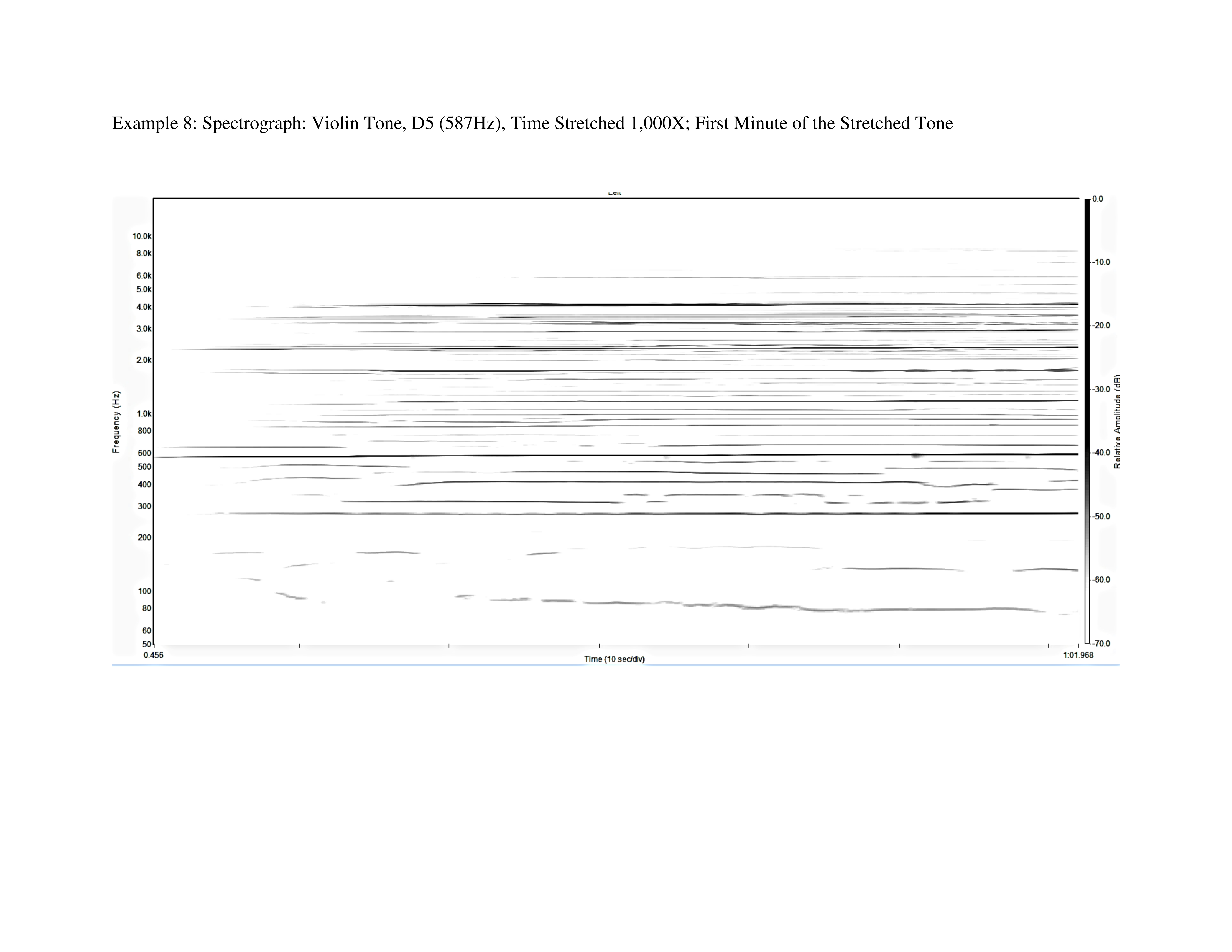

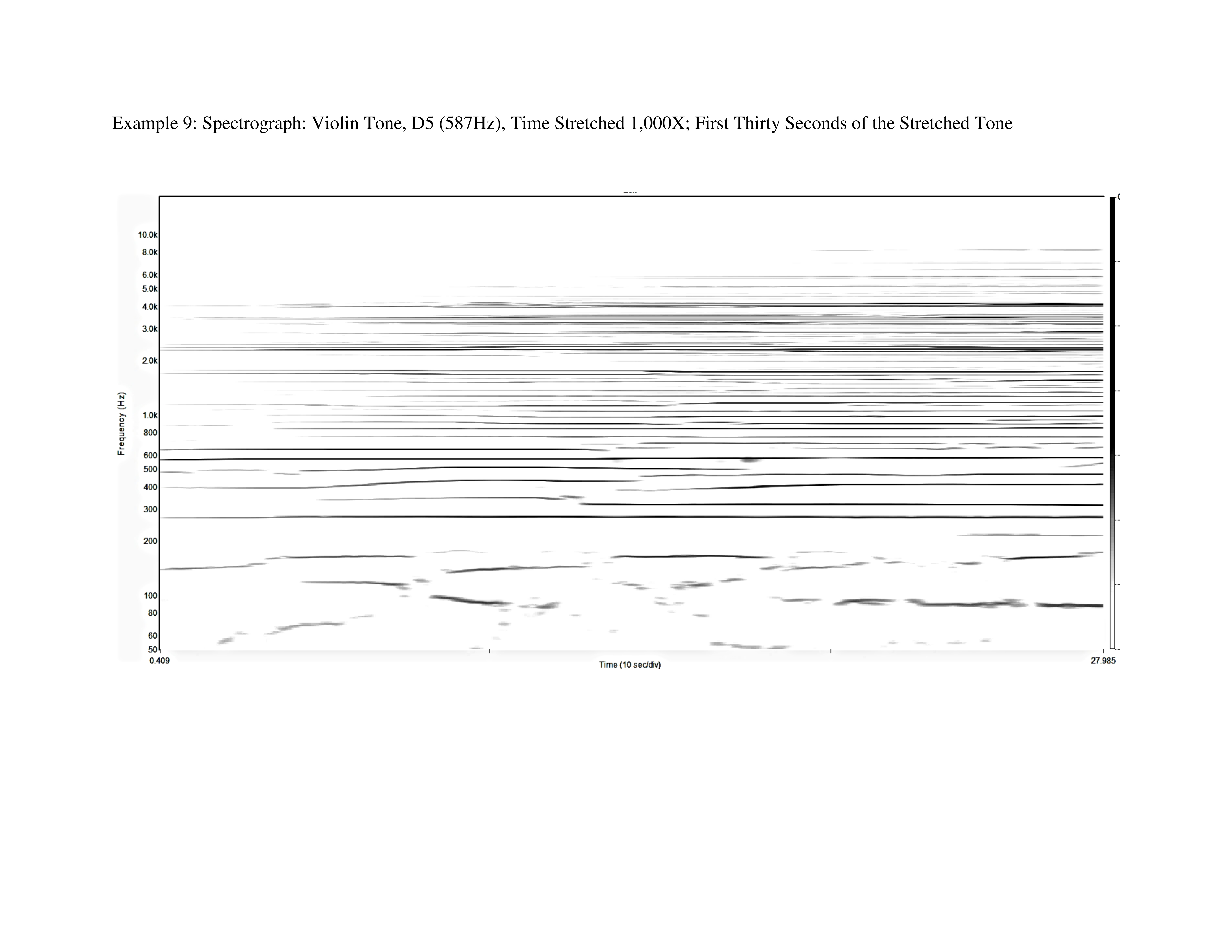

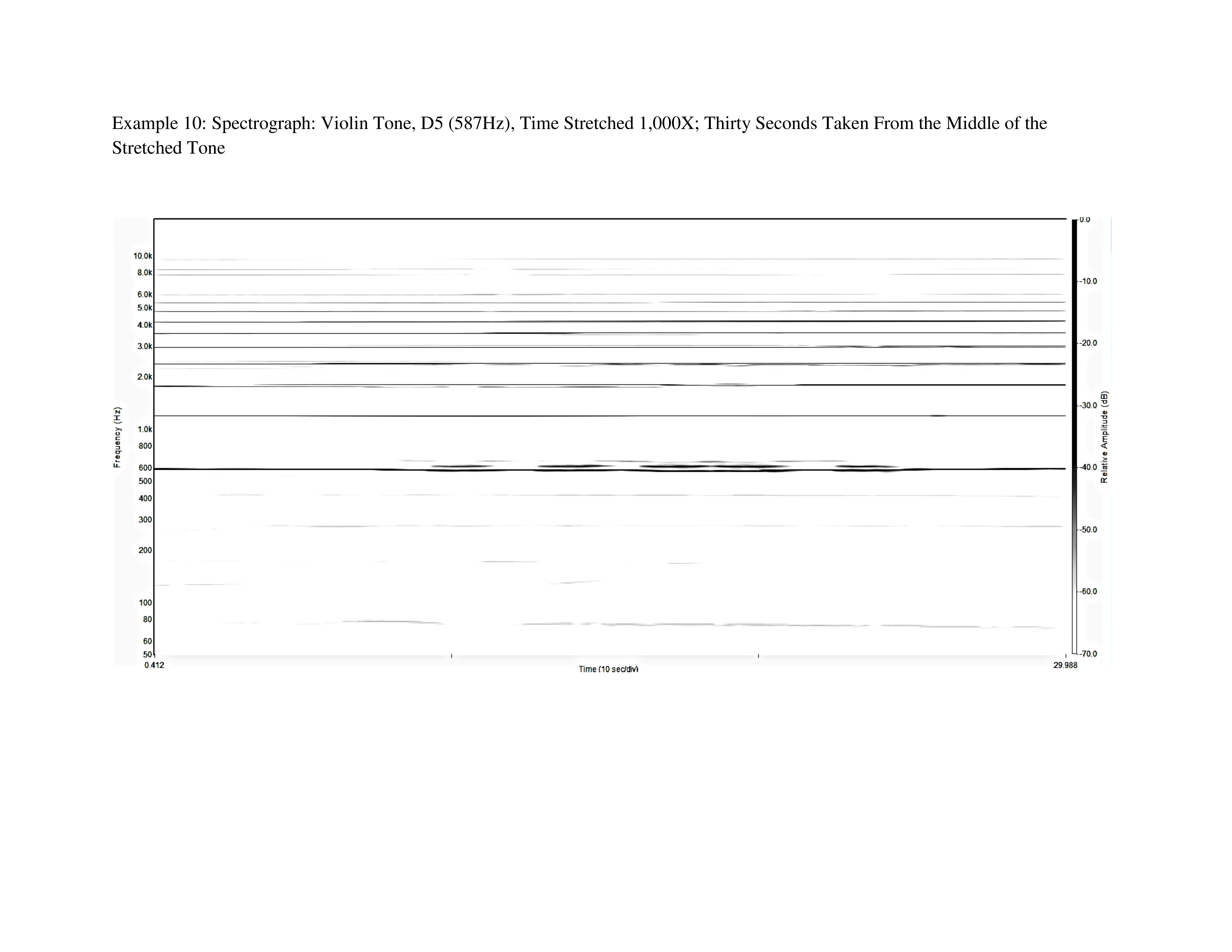

For example, if we examine a spectrograph of a D5 played by a violin in real time, we see what appears to be a steady tone without inflection, both with respect to its fundamental as well as its overtones (Example 7).12Spectrographs of a violin tone appearing in Examples 7, 8, 9 and 10 were drawn from the McGill University Master Sample Series, CD #1, Solo Strings and Violin Ensemble (Montreal: McGill University), 1987. Spectrographs were created with the SpectraPLUS FFT Spectral Analysis System manufactured by Pioneer Hill Software. Moreover, there is little evidence of any attack transients. If, however, we time stretch the first minute of this tone by a factor of 1000 and examine its spectrograph we see all the fluctuations of pitch that are part of the transient noise produced when the bow first engages the string (Example 8). Attack transients occur at the onset of a tone when produced by an instrument. They may contain numerous frequencies both higher and lower than the pitch finally achieved in the sustained phase of the tone as well as numerous noise elements. The complex and varied nature of these transients is even more apparent if we examine a spectrograph of one thirty-second detail of the aforementioned violin tone stretched by the same factor of 1000 (Example 9). Similarly, if we examine a thirty second sample taken from the middle of the sustained phase of this stretched tone we can see that, even here, the tone is not at all steady but contains numerous microtonal inflections and glissandi that give this astonishingly active and complex sonority a sense of depth and life (Example 10). It is this aspect of the tone that Scelsi appears to be amplifying in his work.

For example, if we examine a spectrograph of a D5 played by a violin in real time, we see what appears to be a steady tone without inflection, both with respect to its fundamental as well as its overtones (Example 7).12Spectrographs of a violin tone appearing in Examples 7, 8, 9 and 10 were drawn from the McGill University Master Sample Series, CD #1, Solo Strings and Violin Ensemble (Montreal: McGill University), 1987. Spectrographs were created with the SpectraPLUS FFT Spectral Analysis System manufactured by Pioneer Hill Software. Moreover, there is little evidence of any attack transients. If, however, we time stretch the first minute of this tone by a factor of 1000 and examine its spectrograph we see all the fluctuations of pitch that are part of the transient noise produced when the bow first engages the string (Example 8). Attack transients occur at the onset of a tone when produced by an instrument. They may contain numerous frequencies both higher and lower than the pitch finally achieved in the sustained phase of the tone as well as numerous noise elements. The complex and varied nature of these transients is even more apparent if we examine a spectrograph of one thirty-second detail of the aforementioned violin tone stretched by the same factor of 1000 (Example 9). Similarly, if we examine a thirty second sample taken from the middle of the sustained phase of this stretched tone we can see that, even here, the tone is not at all steady but contains numerous microtonal inflections and glissandi that give this astonishingly active and complex sonority a sense of depth and life (Example 10). It is this aspect of the tone that Scelsi appears to be amplifying in his work.

Whether part of the attack or sustain, components of tone production, such microcosmic fluctuations, affect our experience of sound — indeed they can often determine our ability to distinguish one musical instrument from another, even when playing the same tone! These fluctuations become the very subject of Scelsi’s compositions, in which they are amplified and rendered more readily audible. In turn, these amplifications become the substance of his music, both in terms of form and expression. As Tristan Murail, a composer of so-called spectral music has observed:

Whether part of the attack or sustain, components of tone production, such microcosmic fluctuations, affect our experience of sound — indeed they can often determine our ability to distinguish one musical instrument from another, even when playing the same tone! These fluctuations become the very subject of Scelsi’s compositions, in which they are amplified and rendered more readily audible. In turn, these amplifications become the substance of his music, both in terms of form and expression. As Tristan Murail, a composer of so-called spectral music has observed:

Scelsi’s intuitive grasp of acoustics is remarkable. He exploits, probably unconsciously, acoustic phenomena such as transients, beats, the width of the critical bands, etc.13Murail, “Scelsi, De-composer,” 178. In a footnote attached to this citation Murail also writes that: Closely spaced pitches give rise to beats of ‘chorus’ effects, which enrich the sonic texture when the pitches spread apart a little , one enters the zone of ‘dissonance’; when they spread further, one gets the sense of ‘consonance’. The notion of the critical bank is in a certain respect a theoretical justification for the intuitive idea of the ’depth’ of the sound.

Most discussion of Scelsi’s work comments upon his exploration of the overtone series, but, as this analysis shows, and as Murail notes, his music emphasizes and expands upon many more aspects of sound than just overtone spectra. Murail met Scelsi while studying in Rome and spent a great deal of time with him for a number of years.14Anderson, “Tristan Murail,” 672-673. Some of his observations on Scelsi’s working methods reinforce these observations:

One day, long ago, when I [Murail] was visiting him, Giacinto Scelsi showed me how he worked: by his piano was an ondioline, and two tape recorders (the ondioline was a kind of early synthesizer, which could produce a variety of sounds, and which, most importantly, allowed controlled vibrato and micro-intervals). With this equipment, he improvised and recorded layer after layer of sounds, thus creating a sort of sketch or simulation, of the future piece – what we can now do much more easily and convincingly with computer software.15Murail, program note for the composition Un Sogno for ensemble.

Murail also notes that:

For Scelsi, the principal object of composition then becomes what he calls the ‘depth’ of the sound...[he] is thus concerned with dynamics, densities, registers, internal dynamism and the timbral variations and micro-variations of each instrument: attacks, types of sustain, spectral modifications and alterations of pitch and intensity. String instruments are obviously ideal for such writing, because of their great flexibility and fine control of timbre...[my italics].16Murail, “Scelsi, De-composer,” 175-176.

As if putting a single tone under a microscope, in L’âme ouverte Scelsi makes us conscious of sonic attributes that we typically gloss over when we experience as apparently simple a sound as that of a violin holding a single tone. In doing so he draws our attention to the sonic richness embedded within every sound that we experience. He truly reconnects us with sound as he reveals to us aspects of its inner life that we often ignore. Returning to John Dewey, we can now see that Scelsi indeed does enable us to “...perfect the power to perceive.”17Dewey, 325.

This is not fantasy. As has been noted by the Scelsi himself, he often listened intently and repeatedly to isolated, individual sounds as he taught himself to perceive this inner life.

I began to play the same notes [on a piano] over and over... By repeating the same note for a long time, the sound becomes bigger, so much, in fact, that one hears harmonies around it and around oneself while being enveloped by the sound. I can assure you that it is an extraordinary experience; the sound contains an entire universe, with harmonies never heard otherwise. The sound fills the space around you; you can swim in it. The sound is both a creator and destroyer agent....Ultimately you penetrate the sound, you become part of it, swallowed little by little until there is no need for another sound. Music today [has] become an intellectual game, combining [one] sound with another etc...Everything is at the center of a sound, the entire universe fills the space, and all possible sounds are contained in it.18Mallet, “Il suono lontano: Conversazione con Giacinto Scelsi,” 25; quoted by Montali in “Conceptual Reflections and Literary Evolution in Giacinto Scelsi’s Works,” 64.

What Scelsi came to understand, and what the aforementioned spectrographs clearly show, is that a single tone is never constant and unvarying; it bends, bifurcates, stutters – all on the microscopic level. In L’âme ouverte Scelsi has deconstructed the complex sound that a violinist makes when drawing a bow across a string, and then reconstructed that sound in slow motion, reshaping it into a unique formal design replete with amplifications of these same bends, bifurcations and stutters. He has recomposed this sound literally from the inside out.

Comparison of both pieces

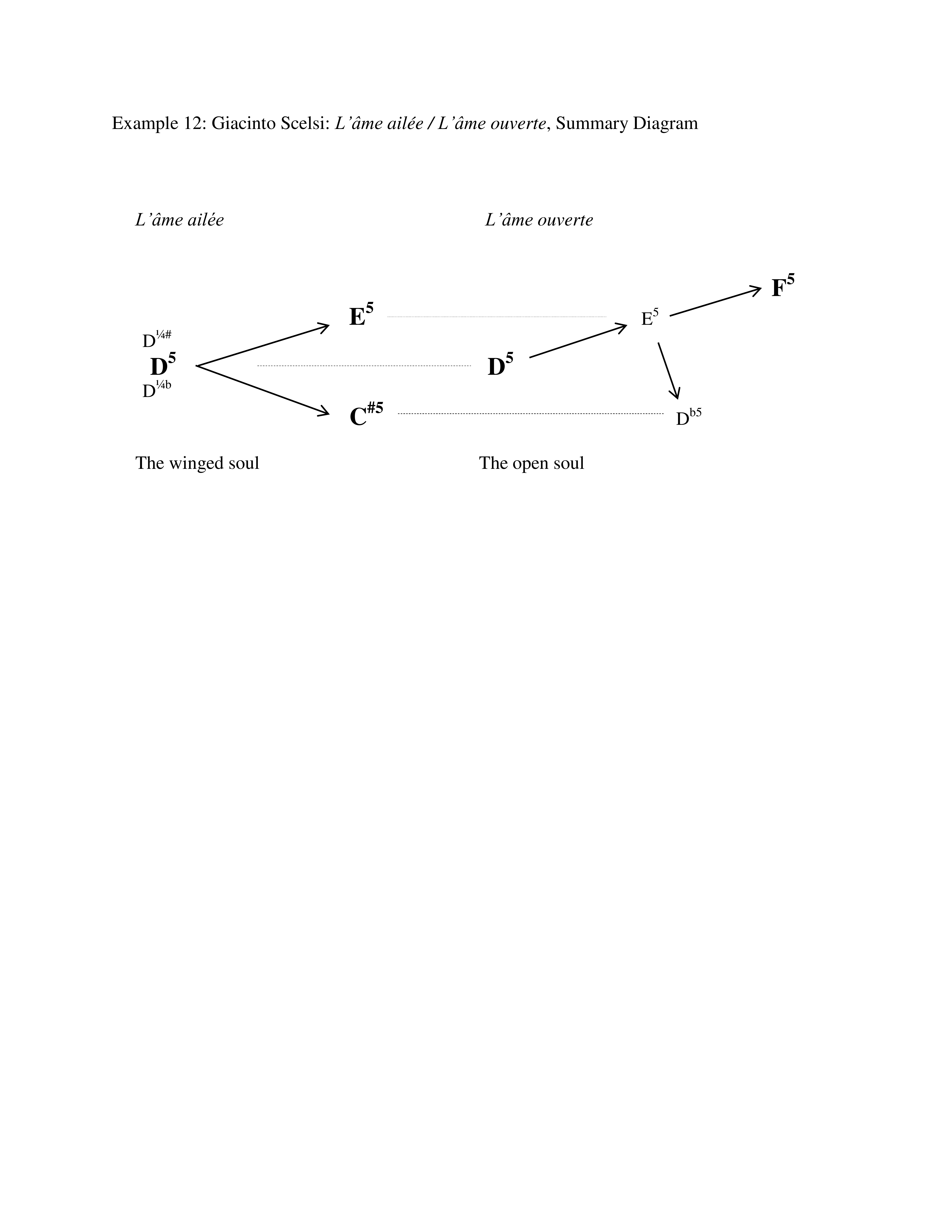

Briefly, the first piece of the set, L’âme ailée, expands outward from a single central tone to a minor third. In a sense, it discovers the boundaries of this space as it expands outward from its center (Example 11). Scelsi constructs the third as though he had no prior knowledge that such a space existed. He does so with great tension, carving it out of the sound of the violin as he explores every facet of the space that instrument is trying to circumscribe. In contrast, one might say that, in the second piece, which we have just discussed at length, L’âme ouverte, he steps into the minor third, starting at one end point and evolving to the other, again, with great tension. The space of the minor third is itself not the focus, certainly not as a simple element in a linguistic field (tonal, serial...). It is only significant as an isolated instance of a complex sonority. In each of these two pieces, form may be identified as the process creating such a sonority (hence, the internal fluctuations of sound - microtones, beats, changes of amplitude - that are heard as the sonority is formed).

L’âme ailée is more internally active than its partner L’âme ouverte. Unlike the latter, which ends on a unison, the former evolves to and ends on a minor third C#5-E5 (Example 12). Building upon the general sense of expansion we feel within each piece, Scelsi constructs the second piece, L’âme ouverte, around a minor third (D5-F5) that is a half-step above that of the first piece, L’âme ailée, (C#5-E5). However, both pieces start in the region of D5: the first piece expands outward in both directions from D5 (first exploring microtonal regions below D5, then those above), while the second, as we have noted, expands only upward. Curiously, at one point, as L’âme ouverte rises from D5 to F5, it drops back down slightly to Db5. Perhaps this slight dip is intended to recall the Db5 (C#5) which became the lowest point of the first piece, L’âme ailée. Of course, such pitch relationships merely constitute the scaffold upon which Scelsi stands as he enters the world of a sound – in this case that of a violin. As noted Scelsi scholar Alessandra Montali has observed:

L’âme ailée is more internally active than its partner L’âme ouverte. Unlike the latter, which ends on a unison, the former evolves to and ends on a minor third C#5-E5 (Example 12). Building upon the general sense of expansion we feel within each piece, Scelsi constructs the second piece, L’âme ouverte, around a minor third (D5-F5) that is a half-step above that of the first piece, L’âme ailée, (C#5-E5). However, both pieces start in the region of D5: the first piece expands outward in both directions from D5 (first exploring microtonal regions below D5, then those above), while the second, as we have noted, expands only upward. Curiously, at one point, as L’âme ouverte rises from D5 to F5, it drops back down slightly to Db5. Perhaps this slight dip is intended to recall the Db5 (C#5) which became the lowest point of the first piece, L’âme ailée. Of course, such pitch relationships merely constitute the scaffold upon which Scelsi stands as he enters the world of a sound – in this case that of a violin. As noted Scelsi scholar Alessandra Montali has observed:

Referencing Goethe’s theory of colors, Scelsi points out the fact that the type of sound under discussion is preexistent in its sensitive and physical manifestations. Vibrations are not the origins, but, rather, the means, the conduit through which sound manifests itself to our limited hearing ability...

Moving on from these theoretical premises, Scelsi elaborated on a revolutionary creative method that was based on the decomposition of sound in the spectral parameters of the harmonic formants...19Montali, “Conceptual Reflections and Literary Evolution in Giacinto Scelsi’s Works,” 69-70.

As is the case with many new developments in the arts, ideas are often ‘in the air,’ being explored by a number of different artists, unbeknownst to one another, around the globe, even in the same time period. In 1950, almost a decade before Scelsi composed his landmark Quattro Pezzi, the American composer Elliott Carter wrote his Eight Etudes and a Fantasy for wind quintet. The seventh etude of this set is a study on one note in which Carter explored, among other things, the aural effect of attach noise upon our ability to differentiate instrumental timbres.20See Cogan, “Carter’s Pair o’ Diamonds.” This lecture contains detailed analysis of Etudes III and VII from Elliott Carter’s composition Eight Etudes and a Fantasy. He also built his structure around the fluctuation of overtones as shaped by changes in instrumentation and amplitude. Carter, of course, abandoned such a focused approach to composition based upon a single tone, but certainly continued, throughout his career, to place great weight upon the use of tone color as an expressive and structural device. Certainly his early exploration of the properties of a single note in this seventh etude must have helped shape his individual approach to composition, as much as his use of pitch/interval sets and pulse modulations.

Similarly, in 1966, several years after Scelsi’s Quattro Pezzi, Gyorgy Ligeti created his famous Cello Concerto, the first movement of which begins with a lengthy exploration of the inner workings of a single note, after which the music evolves toward more diverse pitch combinations. In this work, as many others by this composer, the distinction between pitch and timbre becomes increasingly blurred. Typically, as his compositions unfold listeners gradually abandon any sense that these two aspects of sound are at all separable.

Scelsi’s own work has been quite influential, especially in Europe, perhaps most notably among composers of so-called spectral music including the aforementioned Tristan Murail, as well as Gérard Grisey, Hughes Dufort, Michael Levinas, among others. 21See Anderson, "A Provisional History of Spectral Music"; Feineberg, Spectral Music: History and Techniques; and, Fineberg, Spectral Music: Aesthetics and Music. Using acoustic instruments as well as electronics these composers literally orchestrate complex, time varying sound spectra, creating a kaleidoscopic array of new sonorities. In their works form becomes synonymous with the constant evolution and dissolution of a succession of such spectra.

Scelsi’s work also bears some similarity with certain early works of the so-called minimalist composers in the United States in the 1960’s. LaMont Young’s Composition 1960 #7 consists of a fifth (B and F#) and the instruction "To be held for a long time." A forty-five-minute performance of this piece was presented by a string trio in New York in 1961.22Alburger, “La Mont Young to 1960,” 4. As a result of sustaining this sonority for a very long time the audience gradually began to notice all the fluctuating overtones and noises incidental to the sustaining of such a seemingly simple drone. Musicologist H. Wiley Hitchcock has remarked that this piece “revealed to those who continued to listen a whole inner world of fluctuating overtones in the open fifth as sustained by the players.”23Hitchcock, Music in the United States: A Historical Introduction, p. 272. In a similar vein, in Steve Reich’s early tape-loop pieces It's Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966), a simple phasing process enabled the composer to tease apart the inner components of the sound of the human voice.24For recordings of these works see, Steve Reich: Early Works. These compositions, of course, are now widely known as examples of minimalism in music. In each, the composer set in motion a process through which the inner life of a sound gradually was rendered perceptible to the listener. However, in these works the composers never took the elements of sound that their processes revealed and then used these as material to be reshaped into a new, more complex sonic work. In contrast, Scelsi was never a minimalist, in any sense of that word. Indeed, if one must resort to applying labels to compositional styles, one certainly, more accurately, should consider him a sonic maximalist; a composer who embraced all dimensions of his sonic material and used these to consciously shape rich and complex musical designs.

In L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte, among many other works, Scelsi literally decomposes sound into its many elements, and then transforms those elements into truly original musical designs. His compositions offer the attentive listener an opportunity to engage the sonic world in which he/she lives with greater sensitivity and insight. For Scelsi, the process of composing from the internal parts of a sound outward leads to a complete recognition of the complex nature of our aural experience “through which sound manifests itself.”

Notes

1 Dewey, Art as Experience, 325.

2 Sciannameo and Pellegrini eds., Music as a Dream: Essays on Giacinto Scelsi.

3 For an excellent introduction to Rudhyar’s work see Ertan, Dane Rudhyar: His Music, Thought, and Art.

4 Reish, “Una Nota Sola: Giacinto Scelsi and the Genesis of Music on a Single Note.” 152.

The books by Rudhyar referenced in this citation are The Rebirth of Hindu Music and Art as Release of Power: A Series of Seven Essays on the Philosophy of Art.

5 In Schenker’s view the so-called “chord of nature” – a concept not original to Schenker alone – is derived from the first five overtones of a fundamental frequency, which together constitute the tones of a major triad. Schenker saw this chord, and its expansions, as the source of tonal composition.

6 The most comprehensive use of spectrographs in the study of music is found in the work of theorist Robert Cogan, whose book New Images of Musical Sound represents a landmark in the development of this type of analysis, using musical examples drawn from a variety of eras and cultures.

7 Campbell and Greated, The Musician’s Guide to Acoustics, 142.

8 Scelsi, L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte.

9 Spectrographs of a recorded performance of L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte appearing in Examples 2 and 11 are taken from a performance by Barbara Lüneburg, violin, on the CD Beyond: Bach, Scelsi. Other performers have recorded the work: Weiping Lee, Giacinto Scelsi: The Violin Works; and Robert Zimansky, Giacinto Scelsi. However, the Lüneburg performance appears to be the most accurate. Spectrographs were created with the SpectraPLUS FFT Spectral Analysis System manufactured by Pioneer Hill Software. On the spectrographs the horizontal axis represents time and the vertical axis frequency measured in cps. The image reveals not only the motion of fundamental frequencies but that of their overtones as well.

10 “In acoustics, a beat is an interference pattern between two sounds of slightly different frequencies, perceived as a periodic variation in volume whose rate is the difference of the two frequencies. When tuning instruments that can produce sustained tones, beats can be readily recognized. Tuning two tones to a unison will present a peculiar effect: when the two tones are close in pitch but not identical, the difference in frequency generates the beating. The volume varies as in a tremolo as the sounds alternately interfere constructively and destructively. As the two tones gradually approach unison, the beating slows down and may become so slow as to be imperceptible.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beat_(acoustics).

11 DeLio, “su una nota sola: Giacinto Scelsi’s Quattro pezzi, No. 3 (1959),” 325-355.

12 Spectrographs of a violin tone appearing in Examples 7, 8, 9 and 10 were drawn from the McGill University Master Sample Series, CD #1, Solo Strings and Violin Ensemble (Montreal: McGill University), 1987. Spectrographs were created with the SpectraPLUS FFT Spectral Analysis System manufactured by Pioneer Hill Software.

13 Murail, “Scelsi, De-composer,” 178. In a footnote attached to this citation Murail also writes that:

Closely spaced pitches give rise to beats of ‘chorus’ effects, which enrich the sonic texture when the pitches spread apart a little , one enters the zone of ‘dissonance’; when they spread further, one gets the sense of ‘consonance’. The notion of the critical bank is in a certain respect a theoretical justification for the intuitive idea of the ’depth’ of the sound.

14 Anderson, “Tristan Murail,” 672-673.

15 Murail, program note for the composition Un Sogno for ensemble.

16 Murail, “Scelsi, De-composer,” 175-176.

17 Dewey, 325.

18 Mallet, “Il suono lontano: Conversazione con Giacinto Scelsi,” 25; quoted by Montali in “Conceptual Reflections and Literary Evolution in Giacinto Scelsi’s Works,” 64.

19 Montali, “Conceptual Reflections and Literary Evolution in Giacinto Scelsi’s Works,” 69-70.

20 See Cogan, “Carter’s Pair o’ Diamonds.” This lecture contains detailed analysis of Etudes III and VII from Elliott Carter’s composition Eight Etudes and a Fantasy.

21 See Anderson, "A Provisional History of Spectral Music"; Feineberg, Spectral Music: History and Techniques; and, Fineberg, Spectral Music: Aesthetics and Music.

22 Alburger, “La Mont Young to 1960,” 4.

23 Hitchcock, Music in the United States: A Historical Introduction, p. 272.

24 For recordings of these works see, Steve Reich: Early Works.

Bibliography

Alburger, Mark. 2003. “La Mont Young to 1960.” In 21st Century Music. Vol. 10, No. 3.

Anderson, Julian. 2000. "A Provisional History of Spectral Music". Contemporary Music Review, 19, no. 2.

Anderson, Julian. 1992. “Tristan Murail.” In Contemporary Composers, Pamela Collins and Brian Morton, eds. London: St. James Press.

Campbell, Murray and Clive Greated. 2001. The Musician’s Guide to Acoustics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cogan, Robert. 1976. “Carter’s Pair o’ Diamonds.” Lecture delivered at the National Conference on Music Theory. Boston, MA.

Cogan, Robert. 1984. New Images of Musical Sound. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

DeLio, Thomas. 2008. “su una nota sola: Giacinto Scelsi’s Quattro pezzi, No. 3 (1959).” In Thomas DeLio: Composer and Scholar. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Dewey, John. 1958. Art as Experience. NY: Capricorn Books.

Ertan, Deniz. 2009. Dane Rudhyar: His Music, Thought, and Art. Eastman Studies in Music, No. 61. Rochester NY: University of Rochester Press.

Fineberg, Joshua (ed.). 2000a. ''Spectral Music: History and Techniques.'' Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 2.

Fineberg, Joshua (ed.). 2000b. ''Spectral Music: Aesthetics and Music.'' Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 3.

Hitchcock, Hugh Wiley. 1988. Music in the United States: A Historical Introduction. Eaglewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lee, Weiping. 2013. Giacinto Scelsi: The Violin Works. NY: Mode, Vol. 10, LC29022.

Lüneburg, Barbara. 2013. Beyond: Bach, Scelsi. Darmstadt, Germany: Coviello Classics, No. 61302.

Mallet, Frank. 2001. “Il suono lontano: Conversazione con Giacinto Scelsi.” In Giacinto Scelsi: Viaggio al centro del suono. Pierre Albert Castanet and Nicola Cisternino, eds. La Spezia, Italia: Luna Editore.

Montali, Alessandra. 2013. “Conceptual Reflections and Literary Evolution in Giacinto Scelsi’s Works.” In Music as a Dream: Essays on Giacinto Scelsi. Franco Sciannameo and Allesandra Carlotta Pellegrini eds. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Murail, Tristan. 2014. Program note for the composition Un Sogno for ensemble.

http://www.tristan murail.com/en/ouvre-fiche.php?cotage=29019.

Murail, Tristan. 2005. “Scelsi, De-composer.” Translated by Robert Hasegawa. Contemporary Music Review, Vol. 24, No. 2/3.

Reich, Steve. 1992. Steve Reich: Early Works. New York, NY: Nonesuch Records, No. 979169-2.

Reish, Gregory N. 2006. “Una Nota Sola: Giacinto Scelsi and the Genesis of Music on a Single Note.” Journal of Musicological Research. Vol. 25.

Rudhyar, Dane. 1928, 1979. The Rebirth of Hindu Music. Adyar: India: Theosophical Publishing House; New York: Samuel Weiser.

Rudhyar, Dane. 1930. Art as Release of Power: A Series of Seven Essays on the Philosophy of Art. Carmel, CA: Hamsa.

Scelsi, Giacinto. 1995. L’âme ailée / L’âme ouverte. Paris: Editions Salabert.

Sciannameo, 2013. Franco and Allesandra Carlotta Pellegrini eds. Music as a Dream: Essays on Giacinto Scelsi. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Zimansky, Robert. 1989. Giacinto Scelsi. Warsaw: Accord, No. 200622.