Academics and creative artists frequently recognize the same tensions, desires, and conflicts that exist in society. They both often sense that which is lacking or out of balance in the social fabric, and express the same criticisms of prevalent ideological constructs each in their respective ways. When these social concerns appear in popular music- in a song, throughout the oeuvre of a particular artist, or as a continuous thread that runs through a genre, they typically emerge in fragments, partially realized or developed, sometimes even representing different points of view simultaneously. They might even be expressed in combination with other issues in a vertigo of angst and exhilaration. Academics are sometimes disappointed with the way that social tensions and problems are presented in an all-surface-little-depth manner that they see as fated by the conventions and limitations of popular music.1One thinks, for example, of how influential scholars such as Julia Kristeva have been dismissive of the expressive possibilities of popular culture in works such as Revolution in Poetic Language, and Desire in Language; Terry Eagleton has never voiced approval of any counter-culture music etc. Music that is associated with subcultures, counter-culture movements, or recorded on small independent record labels, however, regularly explores social issues in a more substantive way. Siouxsie and the Banshees, for example, one of the most prominent English cult-acts to appear during the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, made a special province of articulating feminist concerns and depicting gyno-centered traumas in a manner that was especially dramatic and effective. The band was founded in Bomley in 1976 by vocalist Susan Ballion (Siouxsie) and bassist Steven Severin at the height of England’s punk movement; an anti-establishment subculture rooted in the traumatic economic and social changes that occurred in Britain during that era,2For a more comprehensive discussion of the punk movement’s relationship to British society see Dick Hebdige Subculture the Meaning of Style, Tricia Henry Break all Rules, and One Chord Wonders by Dave Laing. To better understand what punk culture meant for women see Lucy O’Brien’s The Woman Punk Made Me and which appropriated and reinterpreted the aggressive and straightforward style of music that originated in New York. It was not long, however, before the deliberately crude, anthemic, overtly political approach of bands like the Sex Pistols came to be seen as one-dimensional, and bands such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, Adam and the Ants, and Joy Division sought to bring more melodic interest and an artier, sophisticated harmonic and textural approach to the London punk style. Later, British (and some American) groups added the influence of glam rock, disco, and electronic dance music to punk rock, and came to rely heavily on synthesizers, which allowed artists to make sophisticated sounds without possessing virtuoso technique, and the new technology came to be heard as an extension of punk's egalitarian spirit. (Mueller 2008, 119) Groups used these new influences and technologies to expand the emotional range of punk music, with bands that would become known as New Wave dwelling on feelings of pleasure and high spirits (Majewski and Bernstein 6Majewski, Lori, and Jonathan Bernstein. Mad World: An Oral History of New WaveArtists and the Songs that Defined the 1980s. New York: Abrams, 14.), while Siouxsie and the Banshees, on the other hand sought sophisticated ways to darken and intensify punk's aesthetic terrorism and social critique.3Music journalist Mick Mercer explains that during the 1980s, bands were divided into genres based more on the composition of their audience, the subculture with which they were affiliated, and the overriding emotional affect of their oeuvre rather than any distinct technical features of their music. See Mueller The Music of the Goth Subculture page 7. They specialized in songs that depicted cruelty on a personal level; in domestic life, and in everyday situations. What was perhaps most noteworthy about the Banshees was their use of Gothicism, which they employed to allow the challenges faced by young, working class, British women to be expressed more fully. Siouxsie and the Banshees were so successful in that respect that their music, image, and the central issues that they articulated became the basis of Britain's goth, or "gothic" movement; a subculture that largely shunned the misogyny inherent in most other types of rock and in other styles associated with subcultures. Angela McRobbie and Jenny Garber note that in England's subcultures women primarily served an accessory to the male participants (115), but goth was perhaps the first subculture to offer expanded possibilities for women. Female participation in motorbike culture (where women came across as unfeeling and subversive), as well as "soft” fashion-based subcultures (such as mod) undoubtedly paved the way for the goth movement, however, the Gothic film and literary signifiers that Siouxsie and the Banshees used in their music and image necessitated "a technically involved relationship with pop culture" that was unusual for women before the emergence of goth (McRobbie and Garner, 115McRobbie, Angela, and Jenny Garber. “Girls and Subcultures,” in The Subcultures Reader, edited by Ken Gelder and Sarah Thornton (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), 112-120.). Siouxsie and the Banshees’s use of Gothicism has been discussed at length elsewhere,4See Charles Mueller “Gothicism and English Goth Music: Notes on the Repertoire.” Gothic Studies. 14/2 November 2012. and that aspect of their artistry is only of peripheral interest to the present study. Instead the focus here will be on the ways in which the group’s work fits into a feminist aesthetic, what Marilyn French refers to as art that approaches reality from a female perspective, that demystifies patriarchal assumptions, and that augments the parameters of style in order to properly render feelings that are difficult to capture when expressing sentiments that are more common to women than to men (68).

The concept of a feminist aesthetic is of course linked to ideas concerning the establishment of a female presence or subjecthood, something that Siouxsie and the Banshees recognized as lacking in the heavier or more aggressive styles of rock that allow artists to create works with a more serious tone than that of their pop counterparts. There is, however, another distinct perspective on gender and subjecthood that can be found in the work of Siouxsie and the Banshees, one that recognizes the importance of what Jean Baudrillard described as seduction, and why its absence from society is responsible for many problems inherent in gender relations in the postmodern era.

In Rex Butler's view, finding new examples to which one could apply Baudrillard's work is of no particular interest because “these examples can only be seen in Baudrillard's terms, they exist not outside but already inside Baudrillard's system, could only be perceived from the beginning because of it. It is a matter neither of confirming or denying Baudrillard's work with examples but of thinking the very conformity of the world to his theory and to what is excluded by it” (18.)The feminist nature of Siouxsie and the Banshees can best be clarified and understood by examining the band's work in terms of this conformity and exclusion in regard to Baudrillard's observations on sex, gender, and seduction, as well as through their interest in established feminist concerns such as the recognition and development of female subjecthood, and justice in gender relations. Much of the dynamicism, tension, and creative energy present in the group’s work stems from the ways that these two distinct approaches to feminism were combined. The music and visual style of Siouxsie and the Banshees has been underrepresented and mischaracterized in both histories of punk rock and gender studies of popular music. Much of the previous scholarship about the group was only concerned with their early work, or failed to explain what was subversive or feminist about their musical artistry. This study reexamines the band’s feminist contribution to popular music, how the members were sensitive to the tensions involving young British women and their position in society at a time when phallic masculine sensibilities were creating highly destructive social situations.5The late 1970s and early 1980s saw massive labor unrest in England along with crushing unemployment. One could also point to the violence in Northern Ireland and its repercussions in England proper. Europeans lived under the specter of American and Soviet nuclear struggles at that time. Thatcher’s conservatism was based, ironically, on patriarchy and a phallic ideology. It also serves as an example of how feminist expression was forced to become, at once, more subtle and more flamboyant during the excess and conservativism of the 1980s.

Seduction, Feminism and Music: Influences

A group such as Siouxsie and the Banshees, who based their act on the play of themes and signifiers of seduction naturally were inspired by bands who embraced ambiguity and irony, as well as those who shunned blues-based conventions due to their stereotyped connotations of authenticity, and virtuosity, which, in turn, typically serve as signifiers of masculine production and accumulation. 1970’s glam-rock icons David Bowie and Marc Bolan were obvious influences with their emphasis on pure appearance and lack of meaning, as well as their ironic presentation of blues-based rock, and their love of parody. Ballion’s image may have been inspired by cabaret and torch singers who have come to signify seduction, narcissism, world-weariness, despair, and urban chic (Moore 265), but it is hard to discern their influence in most of the band’s music.6The Group did record a camp cover of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” and the track “Peek-a-boo” features oomph-pa-pa figuration that was often used in cabaret numbers. How much of Ballion’s vocal style was shaped by music theater, or torch singers is open to conjecture as it is difficult to pinpoint any clear melodic signatures or vocal techniques from cabaret. The Velvet Underground, both with and without Nico (as well as Nico’s collaborations with Brian Eno), were far more tangible influences, which comes as no surprise for even today critics find it difficult to categorize the band’s music. Ballion and the other group members emphasized their high regard for the way that the Velvet Underground’s music generated tremendous impact through an economy of means such as half-spoken lyrics, minimal drum work, and drone-like, repetitive accompaniments. This admiration is very evident in the Banshees’ music. The Underground’s music, however, was firmly rooted in the pop, blues, R&B, and folk-rock popular during the late 1960s, but with lyrics that dwelt on the dark side of Warhol’s factory, drug addiction, and the often harsh realities of street life in inner-city New York. Their use of drones, repetitive structures, and dissonant sound effects were employed to disrupt conventions, to give their melodies and harmonic progressions an unsettling feel to match the content of the words, and to provide avant-garde sign-value. The Banshees, on the other hand, wrote lyrics that were often more surreal and ambiguous in meaning. They used drones, sound-effects and extended techniques (devices that they also admired in horror film soundtracks) to create a greater sense of intimacy between the words and the music than what the Velvets had been able to achieve. The originality of the Banshees’s lyrics would have been lessened through the use of established rock conventions, and would have contradicted the Banshee’s desire to ridicule any style that society celebrated as “authentic,” and with all the connotations of masculinity associated with that term.

What Ballion and the band’s co-founder Steven Severin most admired about Andy Warhol’s famous collaborators was the way that they set their disconsolate poetry to music that was unpretentious and chic, skillfully experimental without being overly intellectual. The Velvets achieved their effectiveness without recourse to rock virtuosity. The way that Ballion and Severin recall using the style of the Velvet Underground as their yardstick when auditioning new band members sheds light on their feminist approach: One guitarist was rejected because “he was a real rock guitarist, always trying to put licks into songs and making funny faces when he played. We spent most of the time trying to make him forget what he learned; the mesmeric drone of the Velvet Underground was the blueprint for what we wanted and he was having none of that” (Paytress 29Paytress, Mark. Siouxsie and the Banshees: The Authorized Biography. London: Sanctuary, 2003. ). Severin adds, “If someone had showed up and played ‘Waiting for the Man’ on just two chords, and made some kind of silly discordant sound they’d have probably gotten the job immediately. Instead they showed up to noodle for ages. It was horrible. What we wanted was someone who knew the value of being mesmerizing without being a rock virtuoso. And they had to look right. That was probably most important because we had a very precise idea of how the band should look” (Paytress 57).

It is significant that Baudrillard, who seldom mentioned specific figures from pop culture in his writing, singled out Nico, the Velvets’s famous frontwoman, as an icon of seduction. Nico was more concerned with playing with signs of sex than sex itself. She was alluring in an artificial non-sexual way through a combination of masculine and feminine elements (1979, 12-13). Considering how hard they strove to incorporate those same qualities into their own image and sound, Ballion and Severin clearly admired the sense of ambiguity and artificiality that Nico personified.

Even among their predecessors in the British punk scene Ballion and Severin expressed distain for groups preoccupied with identity, value and meaning. Discussing the difference between England’s two iconic punk groups, the Clash and the Sex Pistols, Severin remarked:

I thought they [The Clash] were fantastic but I felt there was something very traditional about what they were doing. There was always this kind of worthy thing about them and you never knew which side of the fence they were on. There was something more debauched about The Pistols, and that was obviously more attractive. The Clash were more sincere and a bit humorless. With The Pistols there was always a point in the show where I’d be howling with laughter. (44).

Siouxsie and the Banshees were obviously inspired by the ways that the Sex Pistols violated the masculine logic of utility and gave up all pretenses of authenticity and sincerity.

Ballion embraced the seductive allure of artifice, stating that her fascination with the power of conventional feminine beauty was rooted in her admiration for the lifestyle of go-go/burlesque dancers and the sexually mesmerizing effect that they are capable of exerting (Punk: The Early Years). Ballion clearly wanted her interest in vamp glamour to be understood as a reflexive choice based on her personal feelings and tastes rather than interpreted as pleasurable submission to the male gaze, or blind obedience to gender norms. The seductress, after all, is supposed to be powerful and autonomous, someone who forces others to form their identity through and around her. Ballion recognized that to the general public, traditional signifiers of gender are understood as an essence or irreversible identity, a fact that she used to her full advantage. Ballion's Siouxsie persona signified that women could be strong and successful without being tomboys, and that femininity and success need not be mutually exclusive. Her celebration of artifice stems more from the desire to thwart masculine ideals of depth and positivity rather than to dramatize the signifying gestures and performativity of gender. Ballion seems to have subscribed to the idea articulated by Rosi Braidotti that traditional signifiers of femininity should not be relinquished by women until they have achieved full subjecthood (89-99). Ballion is what Judith Butler would call a “humanist feminist,” attacking gender hierarchy and heterosexual relationships of subordination but less interested in expanding the possibilities of gender and deconstructing the binary frame (XXX). In a Butler inspired reading, Siouxsie would only be subversive in terms of her challenge to paternal law, the violation of which was nevertheless a powerful gesture in the context of the Reagan/Thatcher era when the paternal law was celebrated to the near eradication of the feminine. (Ballion's image will be discussed in more detail subsequently).

Attacking the Logic of Production: The Late 1970s

In For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, and its companion piece Seduction, Baudrillard contemplated how late-capitalist societies are nearly devoid of any feminine sensibilities. A distinctly male drive to produce, accumulate, dominate, control, categorize, classify, and scrutinize has permeated nearly every aspect of human existence. This lack of balance between the masculine and the feminine was also noticed by Siouxsie and the Banshees who mocked and ridiculed masculine power and the logic of production and accumulation frequently in their early recordings. Considering the member's punk background, the anti-establishment nature of British punk itself, and the group’s feminist sympathies, the rigid masculine ideaology of production and accumulation was an obvious target. Masculine ideologies typically obliterate all that is symbolic as well as the cyclical processes of exchange that had previously been the basis for rewarding human interaction. Masculinity in late capitalism is also based in the creation of a positive, non-reversible assumption of identity (Grace 142Grace, Victoria. Baudrillard’s Challenge: A Feminist Reading. New York and London: Routledge, 2000.). The ultimate consequence of the supremacy of accumulative logic is the abolition of the feminine, and the reduction of love, desire, and meaningful relationships into games that resemble the management of investment capital. Baudrillard's Marx-based criticism and Ballion's punk- derived music both form a synthesis of feminist criticism and capitalist critique, an unusual combination, for as Terry Eagleton observes, gender criticism generally does not address capitalism's excesses. Instead it provides post-1960s scholars with a means of being subversive and radical without advocating any real changes to the system (69). For Ballion and Baudrillard, however, the masculine impulse to accumulate and dominate is inexorably linked to society social, economic, and interpersonal problems.

An example that illustrates Siouxsie and the Banshees’s technique of lampooning masculine logic is “Metal Postcard” from their debut album The Scream (1978). In a portion of her book Women and Popular Music, Shelia Whiteley briefly discussed the song as an example of “the scream of feminized punk” but did not identify the most strikingly feminist characteristics of the music. Whiteley’s analysis focuses on ways in which the early albums by Siouxsie and the Banshees were as aggressive, abrasive, and as confrontational as all-male punk bands. But Ballion was not entirely about beating men at their own game. “Metal Postcard,” along with many other examples from their first albums, directly caricatured and satirized masculine power and patriarchy.7For example, “Suburban Relapse” discusses domestic abuse. The masculine roots of war are a central focus of Join Hands. Ballion’s sarcastic reading of the Lord’s Prayer epitomizes the group’s attacks on masculine logic. This made the Banshees different from female acts like the Slits who sang about poverty, the destructiveness of the mass media, and the banality of suburban living without identifying its root cause. “Metal Postcard” was said to have been prompted by a speech given by Herman Goering (Thompson, 42Thompson, Dave. The Dark Reign of Gothic Rock. London: Helter Skelter, 2002.), and Whiteley notes that the song was dedicated to Joseph Heartfield, an artist who used photomontage to ridicule the Nazis. Ballion admitted that the idea for the song came to her after viewing an exhibit of Heartfield’s work in 1977.8Susan Ballion notes to Siouxsie and the Banshees, Downside Up (2004), CD, Universal LC6444. The group probably also composed this song as a way to distance themselves from an early controversy where Ballion appeared onstage wearing a Nazi armband strictly for its shock value. Ballion’s faux pas was heavily criticized. Possibly the vocalist found inspiration in this technique because, like punk rock, photomontage requires insight and imagination but no virtuoso technique. It is also frequently based on an aesthetic of ugliness and invites audiences to question the truth behind appearances (particularly in regard to the way the media covers events). Heartfield’s photomontages fascinate and entice the viewer into a nightmarish world where industrialism and the masculine sensibilities of production are presented as grotesque and absurd. Such industrial-themed photomontages also leave one with the sense that all values traditionally associated with femininity such as beauty, empathy, and tenderness have been permanently effaced from the world. The juxtaposition of biological organisms and industrial objects blurs their distinction, leaving one with a sense that the organic being has been violated (a female, particularly a rape victim such as Ballion, might sense this even more acutely).9Ballion has revealed that she was sexually molested by a neighbor at age nine, and that the rape was ignored by her family. See Paytress, Siouxsie and the Banshees pg. 20.

“Metal Postcard” shares many of the same aesthetic characteristics as photomontage. The lyrics caricature and mock the ease with which societies in the twentieth century conformed to media messages and revered masculine, charismatic figures. With its precision of ensemble and its evocation of clockwork, mechanical production, the ostinato figure that accompanies the verses is programmatic, an effect achieved largely through the anapestic rhythm. Like many songs on The Scream “Metal Postcard” was still constructed with “power chords,” intervals of a fifth played on the lowest strings of the guitar and saturated with distortion. Serving as the harmonic foundation of nearly all punk and heavy metal music, power chords are typically considered masculine signifiers (Walser, 42-45Walser, Robert. Running with the Devil: Power Gender and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1993.). When they were employed by Siouxsie and the Banshees, however, the guitar sound was altered with modulation effects that turned the forceful progressions into splashes of color rather than hard-hitting riffs of masculine force.10Songs that illustrate how the band used effects like flanger and chorus to turn power chords away from their “truth” as generic signifiers of masculine power include “Overground,” “Jigsaw Feeling,” “Playground Twist,” and “Mirage.” In “Metal Postcard,” the chords, when combined with the programmatic rhythm, parody rock’s masculine ideology and the logic of production and order. The riff is rhythmically captivating but not a gesture of power since it is a witty satire. The deliberately hackneyed blue-note bends on B-flat that open the song similarly ridicule the masculine obsession with authenticity in rock guitar solos, which are typically based on licks from the blues repertoire. The chorus provides a sense of contrast with its long sustained harmonies, but the equal emphasis given to each beat of the measures maintains the mechanistic atmosphere and draws attention to the rhymes in the text that lampoon the musings of the fictional dictator.

The instrumental timbres reinforce the machine-like quality of the music, implying that punk and heavy metal are formulaic and monotonous. The guitar’s tone is overdriven but not fully distorted, allowing the percussive, metallic snap of the steel strings to be prominently heard. The mix contains a moderate amount of reverb, intensifying the mechanical pulsation of the riff and saturating the ears of the listener with an industrial ambience. The treble and midrange emphasis in the final mix allows the guitar to grate over the bass line. Unlike many rock and pop songs, the narrow-range melody is memorable, clearly defined, and has a recitation-like quality. Ballion’s tone appropriately changes from juvenile defiance during the verses to haughty pompousness in the choruses, as the point of view shifts between a narrator and a dictator. Her shrill and unpredictable glissandos deliberately deface an attractive voice, suggesting that Siouxsie’s femininity was lost and consumed by the logic of masculine production. The musical evidence indicates that band’s motivation for creating ugliness and cacophony was not the same as that of other punk bands with whom they shared anti-establishment sentiments. The difference is that Ballion identified masculine ideologies as the source of the most destructive social ills.

Seduction as a Subversive Strategy

Female recording artists, particularly those associated with subversive subcultures, often face the same challenges that Stéphanie Genz describes as inherent to the action-adventure heroines in comics and films. In her view, the characters become isolated token symbols of female empowerment who cannot shed their female signifiers, which automatically limits how strong or tough they can be. The characters are schizophrenic; split between feminine and masculine traits that result in painful alienation regardless of the boundaries that they may help to weaken in the process (152). Recognizing that the feminine is often linked to seduction through black widow or femme fatal archetypes,11Baudrillard, however, explicitly states that men and women are both equally capable of being masculine/productive or feminine/seductive. Ballion appropriated vulgar seduction with all its power and destruction as a way of negotiating the dilemma that Genz describes.12In Baudrillard's writing, “cold” or “vulgar” seduction is malevolent, and is about destructive control and possession. “Pure” or “hot” seduction is about making deep, transformative connections. However, seduction was also used as a symbolic gesture, to push back against the madness of masculinity as truth, as the scale of value, and to affirm that women need to escape the positivist, productive logic that currently rules gender through seduction. Ballion's use of seduction was not an attempt to create a truth of sex or to create a female subjecthood, but to celebrate the feminine as a negative- a chaotic, destabilizing presence with which to challenge a society based on relentless masculine positivity.

Ballion’s physical appearance, which became the model for goth females, underwent many changes through her career, but it always signified seduction. Baudrillard states that no seductress can be more seductive than seduction itself (86-87), but this was part of the vocalist’s act, what she appeared to be trying to achieve. In spite of Ballion’s unsettling but glamorous appearance, the beauty of her eyes, and the attractiveness of her physical features, the singer did not radiate sex appeal but presented herself as a symbol of seduction rather than a living person, and this may have been what the press was referring to when they characterized her appearance as ghoulish (Morley, 7Morley, Paul. “This is Siouxsie and the Banshees.” New Musical Express, January 1978, 7.). Ballion’s grim, sensual, image complemented her songs, which in most cases portray sex as dangerous.

Whereas contemporary female-fronted bands such as the Slits and X-Ray Specs epitomized the disheveled, rag-bag, street style of punk, (the “walking graffiti” look analyzed by Dick Hebdige), Ballion’s image was always a compilation of symbols of both angst and beauty, more glamorous than punks, but ultimately more disquieting. For most of the band's career, Ballion’s costumes consisted of carefully defaced art deco outfits from the 1920s or English Victorian funeral attire. Occasionally accessories associated with sexual sadomasochism were added. Her hair was styled into a mane of jet-black spikes, and her heavy use of make-up was inspired by the “vamps” of the silent film era and characters from early Expressionist horror films. This mysterious combination of signs served several purposes. It violated the masculine preoccupation with clarity and positivist logic, made traditional ideals of feminine beauty seem strange and unsafe, and disrupted the notion that feminine identity can be reduced to a positivist truth. Visually, Ballion’s Siouxsie persona was a pastiche of signifiers with connotations of seduction, feminine beauty, artificiality, old-world glamour, and melancholy; an image that enhanced considerably the gothic characteristics of the band’s music, and helped to define the visual style of the goth subculture. Although Ballion manipulates signifiers that Baudrillard associates with vulgar, cold seduction, their use in the service of feminist concerns acknowledges Baudrillard’s theory that seduction annuls masculine power; Ballion simply expresses the idea within the language and boundaries of popular music.

Ballion’s use of seduction in her image also creates a subversive radical otherness in a society that Baudrillard believed was driven by a productive logic that destroys symbolic values and exorcises all seductive power (Screened Out, 51). The otherness that she projected through her seductiveness was markedly contrasted onstage with the emaciated-looking males that comprised the Banshees. And although Ballion’s stage persona and mannerisms may have been aggressive and confrontational during the band’s early career, for most of the 1980s she appeared melancholy, misanthropic, and introspective during performances, with minimal body movement and a searching gaze that never made eye contact with the audience or any member of the group. Any sense of camaraderie or rapport among the band was invisible, which made the musicality and tightness of their ensemble even more intriguing. The group’s music and image would not have been so compelling if the audience did not have a thirst for seduction, for anything that is not transparent.

Appropriating Gothicism was an ideal for a recording artist inspired by feminist concerns. For many people, Gothicism is synonymous with danger and ominousness. When the style is used by a female performer a layer of malevolent sign value is added which makes her otherness even more threatening to masculine values. However, there is also an element of “pure” seduction to Ballion’s gothic image allowing her, in Baudrillard’s terms, to efface her desire and identity in the artificial perfection of the sign (Seduction, 94———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.). In his view, cinema idols and other star performers are “sacred monsters,” “no longer beings of flesh and desire, but transsexual, super-sensual beings with the power to absorb meaning that rivals the world’s power of production” (Seduction, 95———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.). The Siouxsie image is the personification of a void or abyss. Perhaps what the music press referred to as her ghoulish qualities were a dramatization of the fact that “the seductress’s face is not the reflection of a soul or sensitivity, which she does not have. To the contrary, her presence serves to submerge all sensibility and expression with a ritual fascination with the void, beneath the ecstasy of the gaze the nullity of her smile” (Seduction, 95———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.). Nowhere was this shown more effectively than in the band’s music videos, as the short films typically featured a pastiche of rapid cutaway images of Ballion’s eyes and face.

What links showbiz glamour and seduction to Gothicism is death. Baudrillard states that: “The death of stars is merely punishment for their ritualized idolatry. They must die, they must already be dead so that they can be perfect and superficial, with or without their make-up. But their death must not lead us to a negative abreaction for behind the only existing form of immortality, that of artifice, their lies the idea incarnated in the stars, that death shines by its absence, that death can be turned into a brilliant and superficial appearance that it is itself a seductive surface" (Seduction, 96-97———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.). David Bowie had previously expressed the emptiness of the cold seductive fascination of glamour with his Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane albums, but Ballion presents a more intense and fatalistic interpretation of the principle appearing as a beautiful captivating corpse.

The way that Ballion used Gothicism to create a feminine interpretation of the punk style made use of both pure and vulgar seduction as each is based on eclipsing perceived notions of truth, turning individuals away from their truth. As the British punk movement was an expression of political discontent, economic anxiety, and an alternative form on nationalism among working-class youths, as well as middle-class uncertainty, the use of gothic signifiers was an ideal way to build upon and intensify the punk strategy of protest through aesthetic terrorism. Gothic films have traditionally been held in low esteem by British society so signifiers associated with that type of cinema carried subversive connotations (Petley, 26Petley, Julian: “A Crude Sort of Entertainment for a Crude Sort of Audience: The British Critics and Horror Cinema.” In British Horror Cinema. Edited by Steve Chibnall and Julian Petley, 24-67. New York and London: Routledge, 2002.). Embracing gothic aesthetics was a means for Ballion to confront prejudice toward the lower-classes (and women), and to attack respectable British values. Thus, in the work of Siouxsie and the Banshees, signs of Gothicism are turned against their truth to become a positive sign of working-class Englishness, the feminine becomes a positive, and death is seduced to signify life and empowerment. Ballion’s use of Gothicism remained consistent with a feminine aesthetic. Her appropriations and allusions are used to attack masculine productive power, and to express difficult emotions rather than as a means to achieve legitimacy, authenticity, authority, or to display accumulation the way Marilyn French notes that male artists do when they plunder the past for signifiers (74).

Seduction, Feminism and Music: Analysis

Siouxsie and the Banshees’s lyrics were typically based on topics such as surreal nightmares, scenes of angst or terror from a voyeuristic perspective, the horrors of childhood, lampooning masculine structures of power, and the depiction of gyno-centered traumas. The accompanying music contained the anxiety, descriptive detail, vivid atmosphere, and disdain for power that characterizes the gothic style, and was achieved primarily by strong bass parts, haunting ostinatos, unusual guitar arpeggio figuration (often with striking suspensions), ominous drones (frequently used to depict masculine sexual energy as threatening), ambient reverb effects, and sensual splashes of instrumental color. The music was frequently tied to the lyrics in a programmatic way.13For example, “Hong Kong Garden” mimics the sound of Chinese instruments and folk-melodies, “Candyman” features guitar parts that imitate the sound of a music box, “Staircase Mystery” contains disorientating panning effects, “Carnival” is enhanced by melodies that sound similar to music often heard at fairs, circuses, and in funhouses. The songs defined what the goth genre would become in both themes and sound. A preoccupation with seduction, however, made the Banshees unique with numerous songs, and even entire albums (such as A Kiss in the Dreamhouse, and Tinderbox) exploring different subversive or destructive aspects of seduction. The music was without question an attack on patriarchy and phallic power structures, and was never apolitical as has been suggested (LReynolds and Press, 282-92Reynolds, Simon, and Joy Press. The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion, and Rock “n” Roll. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.). Desire is largely absent from the songs; in most cases sex was treated as a source of terror.14Two songs on Peepshow, “The Last Beat of My Heart,” and “Ornaments of Gold” could be considered torch-like love songs, but they are anomalies in the Banshees’s oeuvre.

Baudrillard states that seduction is about the immediacy of performance, not establishing a reference or creating a natural order. To that end the Banshees’s music avoids establishing conventions in the way that heavy metal, blues, reggae, rockabilly, etc. are characterized by a handful of standard devices. This is possibly why Ballion resented being seen as the matriarch of goth (Paytress, 107Paytress, Mark. Siouxsie and the Banshees: The Authorized Biography. London: Sanctuary, 2003.). When compared to male groups favored by the goth subculture such as Bauhaus, the Cure, the Mission, etc. the Banshees’s music was overall more intimate and personal in tone, more specific in the shade of emotion being conveyed. It was generally more sensual, more chromatic harmonically, often more dissonant (particularly their early work). Their palette of keyboard and guitar timbres were more varied, and the arpeggio figuration of their accompaniments showed greater imagination. The band’s goal was to avoid establishing references and thus producing a stylistic identity that could be easily defined. Creating music united through Gothicism rather than musical gestures made the goth genre seductive in the sense that it was both there and not there, an absence that eclipsed presence.15Although a minority of music journalists mistook the band's use of Gothicism as an attempt to revive 1960s psychedelia, the majority understood the Banshees's approach. The group was praised for their ability to vividly capture dark moods both lyrically and musically. New Musical Express critic Roy Carr stated that "if Ingmar Bergman produced records they would sound like this." Steve Sutherland praised the music for its tension and energy but thought that the Banshees use of Gothicism was too superficial, not understanding that the group was trying to shun the logic of production, and masculine notions of depth and authenticity. See NME Originals: Goth volume 1 issue 17.

Guitar virtuosity was perhaps the single most abhorrent aspect of rock’s constructions of masculinity in the eyes of the band, and it is not difficult to understand the reason. The British punk scene in general dismissed virtuosity as elitist and contradictory to the rebelliousness that rock was supposed to represent, as well as being at odds with their proletarian values. In Ballion’s feminist interpretation of punk having the guitar in a prominent position would displace the focus on the voice and overshadow the other instruments, a violation of two major components of feminist musical aesthetics (Macarthur, 12-17Macarthur, Sally. Feminist Aesthetics in Music. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.). Robert Walser characterizes guitar virtuosity as a celebration of power and transcendence through musical rhetoric, but a feminist perspective, as articulated by Marilyn French, “considers transcendence illusory or factious and the pursuit of power a fatally doomed enterprise (70). In Baudrillard’s terms guitar virtuosity is incompatible with seduction because it represents mastery as truth; its metaphorical ejaculations (Walser’s term) help sustain the myth of sex as truth. Guitar solos also represent the logic of accumulation that disrupts any process of exchange because it is presented as a non-reversible power.

Generally, the guitar parts in the Banshee’s music are made to sound as unnatural as possible, layered with modulation effects such as chorus and flanger16Modulation effects combine the guitar’s original signal with a detuned and delayed copy. Chorus imparts an ethereal lushness to the guitar’s tone, where flangers create a sweeping effect from high to low, smearing the notes and providing a sense of ambient expansiveness. as well as lush reverb and echo effects. Experimenting with new guitar timbres was unquestionably part of a larger trend in the recording industry during the 1980s, but the use of signal-processing had a special significance in the Banshee’s music. Unnatural timbres helped move the band way from masculine rock authenticity, for as Baudrillard remarked men are never seduced by natural beauty it must always be artificial (Seduction, 90). For the Banshees’s guitarists the effect pedals functioned in a manner similar to how Charles Baudelaire described cosmetics, representing “the need to transcend nature,” making the notes “stronger and more penetrating,” or to impart a “mysterious passion” (Seduction 93———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.). Cosmetics, like the use of these guitar effects, unmask notions concerning authenticity in another way. Baudrillard writes “if what is natural is the real, the imperative, then cosmetics are hypocritical. But if authenticity is a myth then this mythical construction can be put to use in signs which have no natural limits to contend, efface the world through their appearance and disappearance” Seduction 93———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.).

Baudrillard’s observation that artifice can suppress expression and show truth and desire to be unnatural myths is similarly reflected in the Banshees’s use of synthesizer technologies. “Something Blue,” for example, the B-side of the single “The Passenger” from 1986, is a synthetic romantic reverie that embodies the concept musically. The song captures and presents a single affect in the abstract, without a clearly defined sense of time, place, or context. Only one verse is repeated throughout the song, and each return is separated by instrumental interludes that maintain the reflective mood of the vivid daydream.

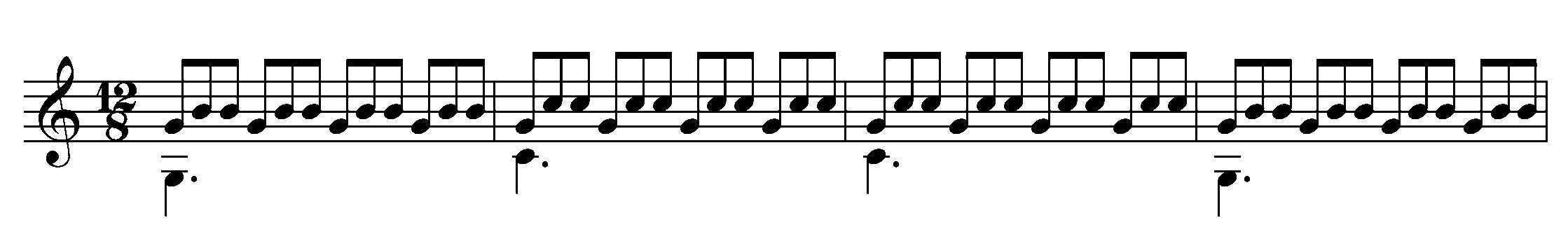

The music exudes and deliberately makes creative use of what Baudrillard describes as the primary characteristic of the seductive portrayal of romance on the screen— “an exercise of the senses that is not the least bit sensual” Seduction 86———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.). For example, the only timbres that are used to accompany the voice are the artificial sounds of an emulator (the first sampling keyboard that produced extremely phony, synthetic replications of the instruments that they were supposed to imitate). In this instance, the synthetic guitar sounds more like a nasal, reedy organ, and the perpetual-motion arpeggios produced by the synthesizer are set to resemble a marimba (see Example 1a). It provides connotations of exoticism that can be interpreted as a nod to the anti-productive values of decadence, "humbling Rome's majesty beneath the effeminate luxury" that the exotic provides (Willsher 13Willsher, James Ed. The Dedalus Book of English Decadence. Cambs: Dedalus, 2004.). The timbres fascinate as a starlet might, that is, they seem too beautiful to possess so little warmth and depth. The instruments were mixed with a considerable amount of digital reverb (set to mimic a large hall), which the Banshees’ seem to use as a metaphor for the impermanence of strong emotions (a fake depth, both fascinating and alluring.). The electronic timbres are so overwhelming that one hardly notices the quality of the chords.

The rippling quality of the accompaniment during the verses and the hollowness of the fifths that occur every other measure, are enhanced by the percussive timbre of the marimba setting on the synthesizer, characteristics that contribute to the music’s insensuousness. Mixed into the background are additional synthesizer parts set to mimic the lush orchestral strings used in film soundtracks. The timbre of the “synthetic” string parts was deliberately used as a tacky counterfeit of a string orchestra, saccharinely sweet and incapable of conveying a sincere sentiment. The music is simply sensuality reduced to an exercise; desire and truth are myths exposed through cosmetics.

Example 1. “Something Blue” a. sampled marimba ostinato

Critics have remarked that very little music from the New Wave movement was particularly passionate in nature; possibly because the artist's viewed musical expressions of love and sexuality as passé and associated them with the banality of 1970s hard rock (Majewski and Bernstein 319Footnote text). The root of their dispassion was different from that of the Banshees, however, who appropriated the values of Gothicism and English decadence, to convey the characteristic “world-weary suspicion of passion,” and cultivate a sensuality that was devoid of tenderness (Willsher 11Willsher, James Ed. The Dedalus Book of English Decadence. Cambs: Dedalus, 2004.). The group's limited use of synthesizers was guided by these sensibilities. For some critics, New Wave's celebration of music technology was a way to bring "modern urban experience to English Arcadia" (Bracewell 39Bracewell, Michael. England is Mine: Pop Life in Albion from Wilde to Goldie. London: Harper Collins, 1998.), and the synthesized timbres signified commercial fashionability, and modern novelty, in the mind of the listener; a celebration of Thatcherism rather than a critique of it. For Siouxsie and the Banshees, synthesized timbres celebrated artifice as a way to thwart masculine depth, an artifice used in the service of seduction rather than production.

Recognizing that feminine seduction is stronger than masculine production, the group composed many songs about the act of seduction capturing the mystery and intensity of either casting the spell or being in the power of another. A particularly effective example is “Melt” from the album A Kiss in the Dreamhouse from 1982. Bassist Severin commented that the title came to him (in postmodern fashion) after watching a television documentary on Hollywood prostitutes during the 1940s who underwent plastic surgery in order to emulate the appearance of movie stars (Paytress, 74Paytress, Mark. Siouxsie and the Banshees: The Authorized Biography. London: Sanctuary, 2003.), tragic victims of the same seduction that Baudrillard would describe thirty-nine years later and the band would dramatize throughout the album by juxtaposing signs of death, and ridiculing masculine production. The lyric persona of “Melt” is an unknown woman, perfectly concealed behind the mask of artifice, the ideal metaphor for the annulment of power. The theme of the song is clearly the dramatization of the seduction, and death of the subject by the object. We really do not know why she is speaking (which is seductive in and of itself). We have no idea of the persona’s goal. Is she mocking, taunting, or simply asking for the surrender of the subject? The gothic style of the lyrics progress in a manner similar to many E.A. Poe narratives where an aggressor treats the victim to an extended description of his fate. Here, however, we are unaware of the persona’s motivations, or if the victim deserves his fate, the song simply describes pure seduction, one-upsmanship, and death. The persona’s only concern is to carry the act through. Although this could be considered an example of cold seduction, the circumstances described in the song are ambiguous enough, and the music captivating enough in its beauty to impart some of the hotness that Baudrillard’s ideal requires.

Every element of the song is designed to envelop and captivate the audience in an atmosphere that is appropriately both impassioned and foreboding. Like a poem by Poe the listener is smothered by unceasing repetition, from the sound of the words, to the rhythms, melodies, and harmonic progressions.17The Raven and A Dream Within a Dream use this technique extensively. The repetitions are rendered all the more effective by the sensual nature of the individual motives. The contrast between the beautiful, lyrical melodies and harmonic progressions and the violence of the lyrics is seductive, marking the only dramatic contrast in the song, which is consistent with the melody of the chorus single-mindedness of seduction. Within the lyrics and music themselves, the contrasts are subtler, but they are responsible for generating considerable tension.

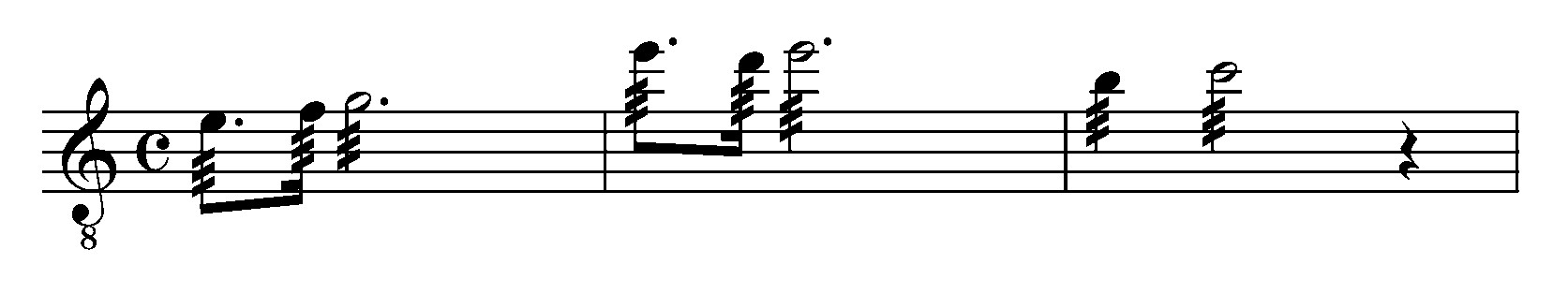

Example 2 “Melt” a. opening guitar theme with rapid tremolo

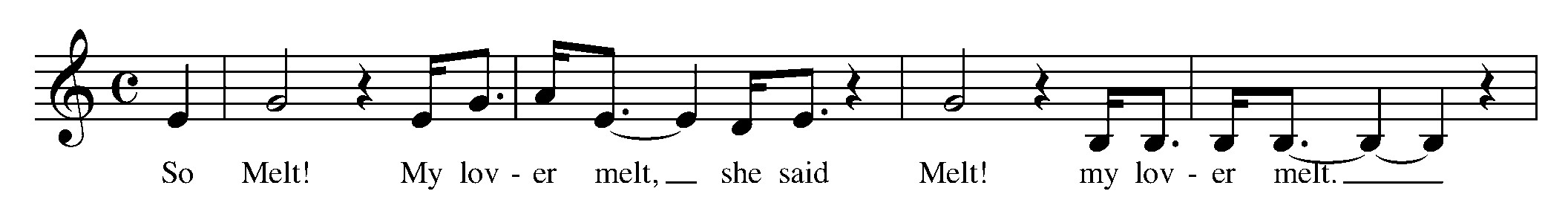

Example 2b.

The only allusions in the song are musical references to films. The flamenco-inspired tremolo guitar line in the introductory measures (Example 2a), the bright, metallic percussiveness of the instrument’s strings, and the harmonic progression evoke the style of Enico Morricone’s film soundtracks, which Ballion cites as an influence.18Susan Ballion, notes to Siouxsie and the Banshees Downside Up: The Singles (2004), CD, Universal LC6444 The Morricone allusions evoke drama and suspense, stylization and artifice, and loneliness, but, perhaps most importantly, they signify the seductive power of the cinema, forever fascinating, blurring the lines between reality and illusion; a ravishing power that Baudrillard genders feminine (Seduction, 95).

The lyrics are intimate and personal in tone but laced with destructive, cruel phrases. Throughout the song, the diction is a double-edged sword, simultaneously cold and tender with carefully chosen metaphors and adjectives: melting (diffusion, impotence, surrender, death), suicide in sex (seductive contradiction, the most uncomfortable phrase in the song), blazing orchids (femininity, sensitivity, beauty, fragility, exoticism concealing danger), beheaded (castration of power), handcuffed in lace, blood, and sperm (passion, entrapment, beauty), funeral of flowers (cold reality in stylized language). The timbres of the voice and guitar mirror the simultaneous sensuality and coldness of the diction. Ballion’s voice is resonant and projects strongly, but her lines are articulated with a quivering vibrato that appropriately signifies weakness. As Baudrillard observes, one always seduces with weakness, not strong signs of power. Guitarist John McGeoch’s tone is similarly sensual (performed on an electric twelve-string guitar with pitch-modulation effect pedals) but also quite metallic and cutting. The effect is both lush and transparent, a false depth.

The incessant descriptive images of melting and suffocation in the lyrics are accompanied by repetitive arpeggio patterns on the guitar and bass. These broken chords convey a sense of disintegration, an idea made all the more effective by the reverb and modulation effects, which soften the articulations, blur the definition of the notes, and take the masculine strength and punchiness out of the bass line.

Harmonies were chosen for their sensual qualities, as well. E-minor is the lushest and most sonorous key available on the guitar (in standard tuning) because it can be rendered with mostly open strings. The harmonies accompanying the verses consist of the alternation between i and iv (E minor and A minor, the two most resonant chords on the guitar), a simple progression but a device used frequently by film composers like Morricone when they wished to create a pervasive sense of melancholy.19A Fistful of Dollars, A Few Dollars More and, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly are just a few of the films where the composer used this device. The harmonies supporting the chorus alternate between i and VI, a gesture that has always been associated with sentimentality or strong feelings of sadness in popular music going back to the 1940s.20“As the Years Go Passing By,” by Deadric Malone, and “Evenin’” by T-Bone Walker are two examples. And since the Banshees wish to keep the listener seduced and “in the moment,” there is not a dominant chord to be found in the song; the slightest sensation of movement would destroy its captivating mood.

The sounds of the words play an important part in the song’s musical evocation of seduction. There are no rhyming words, but the repetition of consonant sounds in the alliterations is unnerving and stands in contrast to the sensuality of the music. The alliterations each have a different connotation: men/melt (eclipse of power), suicide/sex (disturbing contradiction), funeral/flowers (death), breathe/breath (physicality), discipline/devotion (the emotions involved in the song), and, appropriately for a song about seduction, an enchanting reiteration of the word “you.” The captivating repetitions are augmented and magnified by the continuous arpeggios of the guitar and bass parts, and the repetition of the ascending vocal lines of the verses.

Another important source of tension in the song is how the passionate, almost frantic lyrics are sung with strong, continuous, mesmerizing rhythmic patterns. Ballion performs the verses with a strong iambic emphasis on the syllables. However, for a brief moment during each verse she dramatically switches to a tumbling triplet rhythmic pattern in order to emphasize the most powerful phrase. In the first verse, the pattern changes on the words “leads to an insatiable desire.” In second verse, which contains the figurative violence of the seduction, the rhythmic shift emphasizes the castration, “making you choke, making you sigh.” The most graphic imagery comes during the third verse, where Ballion rapidly alternates between iambic and triplet patterns of accent. Her technique creates considerable tension, and clarifies that the subject is completely lost to the object. The caesura at the end of each line marks the end of one complete thought and complements the flow of the rhythmic patterns of the singing. The only caesura that does not occur following a line is after the word, “suicide;” this emphasizes the danger of the physical act, death in sensuality, and the power of the subject over the object. The rhythm of the chorus is sung with an iambic feel but with spondaic accents to emphasize the commands of the seductress, “So Melt!” The patterns of rhythmic accent in the singing are enveloped in an incessant ostinato rhythm of the drums, evocative of a bolero with its tumbling bursts of sixteenth-notes, which complements the Spanish folk-character of the opening guitar melody and symbolizes eroticism; the exotic is often associated with passion and primal desires (particularly in pop culture).

In “Melt,” the listener is immersed in seductive effects, and the structure is at once more static and more ambiguous than the typical verse-chorus format of most punk rock. Ballion and her group brought together a myriad of signifiers of seduction in “Melt;” the song could be considered an example of the nostalgia for seduction that Baudrillard felt was missing from contemporary society, a world dominated by the logic of production. The symbolism in the song fits Baudrillard’s understanding of a feminist statement: “Yes women have been dispossessed of their bodies, their desires, happiness and rights. But they have always remained mistresses of the possibility of eclipse, of seductive disappearance and translucence, and so have always been capable of eclipsing the power of their masters”.

Although the music of Siouxsie and the Banshees was centered on ridiculing masculine power, attacking the logic of production, portraying violence by men against women and children, and expressing the dehumanizing effects of masculine political ideologies, it is worth considering how the group’s use of seduction in these endeavors can be read as a feminist statement. In her essay on feminist aesthetics and their political significance and ramifications, Marilyn French makes a distinction between art that is truly feminist in nature and that which is simply not patriarchal. Art that corresponds to the latter category only stretches and subverts patriarchal standards and values, and presents a sympathetic view toward women’s experiences (70). The most significant quality of feminist art, however, is that it challenges patriarchal ideologies and portrays female experiences wholly and fully.

It could be argued that no products of popular culture can be truly feminist in nature due to their status as a commodity and their inexorable links to the masculine logic of capitalist value. Some might consider Siouxsie and the Banshees’s confrontational music and association with a subversive subculture to violate the feminist concern with harmoniousness; breaking and healing rigid boundaries. Others could point out that many of the group’s most feminist songs were actually composed by male members. However, the Banshees’s music embodied the fears and concerns of young British working-class women, as well as anyone uneasy with the lack of balance between masculine and feminine energies in society. The group was unique in their ability to depict gyno-centered traumas, and confronted patriarchy with seduction and Gothicism in a way that resonated in the British culture of the period. Seduction and Gothicism were also ways to break established conventions in the punk genre in order to win space for feminine sensibilities. In other words, given the limitations of punk rock there was an expansion of language that took place in the group’s music, for the purpose of expressing female experiences that is consistent with feminist aesthetics, and the Banshees did so without making a display of their innovation which would mark their music as masculine.

French feels that another important hallmark of feminist art is that it “focuses on people as wholes; the human is made up of body and emotion as well as mind and spirit; she is also part of a community connected to others” (70). The work of Siouxsie and the Banshees fits this criterion in spite of the restrictions and limitations of pop culture. For example, Tinderbox released in 1987 is an autobiographical song-cycle, or concept record, chronicling the horrors of sexual molestation. Each song, lyrically and musically, represents a different aspect of the experience, from the seduction of the child, to the physical rape, thoughts of revenge, and finally a sense of spiritual healing. Other recordings by the group show a similar variety of the physical, mental, and spiritual when addressing gyno-centered issues. That the group was responsible for defining the musical and visual style of a subculture speaks to how effectively and emphatically they were able to render difficult emotions, and inspire a sense of community in others.

This community, the group’s fan base, and eventually the goth subculture was made up of a majority of females. Music journalist Mick Mercer states: “Goth has the largest female-to-male ratio I have ever experienced {in a subculture} and equality is the watchword. Goth is known as a genre that is not threatening to women; female musicians are celebrated in the subculture, and the genre features more gender diversity in the composition of bands than is typical in other styles. From the 1980s to the present, women also have made up a very high percentage of the best goth DJs.”21Mick Mercer, personal E-mail, 20, April 2005. Mercer’s comments are supported by numerous female informants who participated in goth during the 1980s, and found solace, strength, and camaraderie in the subculture.22See Charles Mueller, The Music of the Goth Subculture: Postmodernism and Aesthetics. PhD dissertation, Florida State University 2008. The British music press was quick to recognize that the music of Siouxsie and the Banshees was considerably different from that of punk and characterized the differences as “feminine” in nature. For example, in the September 1988 issue of Melody Maker Chris Roberts stated “Siouxsie and the Banshees avoid meaning like the plague, and this feline wisdom has served them well.” Two paragraphs later, he notes, “The Banshees can mean anything to anybody, embarrassing the gospel of rationality and clarifying chaos by paying it lipservice with that gloss. The Banshees remain coolly dependent on the slyest of feminine touches” (37). The feminist nature of the group’s approach was polarizing during the 1980s, and many fans of the more misogynistic, masculine styles, such as punk and heavy metal, rejected the band even though they drew attention to many of the same social ills as punk and metal, albeit approaching the problem from the standpoint of gender.

One of French’s most astute insights concerning feminism and literature is that women are always expected to be happy, and if they are not it must be due to their own flaws since the male bar of justice always grants happiness to “good” women. (71). This idea of sweetness, accessibility, and likeability being mandatory for female characters spills over into popular music. Even feminist scholars of popular music sometimes reinforce this stereotype limiting the range of feminist expression. For example, in their book Disruptive Divas, Lori Burns and Melissa Le France shun artists associated with subcultures on the basis that they do not possess the widespread appeal necessary to break patriarchal ideologies in a significant way. Ballion’s music and image makes a point of running against the “good woman” stereotype through Gothicism and seduction. She points the finger at masculine ideologies as the origin of many of society’s most serious problems, but her seductiveness and distinct style signify self-determination; she is an individual who simply does not care about the male bar.

There was little place for the expression of desire and sexual pleasure in Siouxsie and the Banshees music. Their play with seduction and appearances masks a transparent identity and eclipses desire; terms that inscribe and ascribe women into servitude (Grace 153Grace, Victoria. Baudrillard’s Challenge: A Feminist Reading. New York and London: Routledge, 2000.). Although Ballion employed signifiers of seduction in her image her simultaneous use of gothic signs and the aura of melancholy that pervades her performances turn her into a blank that breaks the sexualization of the body without forcefully confronting the male gaze. She confronts anatomy as destiny through excessive artifice, becoming an over-signified. Siouxsie and the Banshees’s use of seduction is a quality that has been overlooked by gender studies of contemporary goth culture that view the band as the subculture’s progenitors, and Ballion as the matriarch. Scholarship such as Goth’s Dark Empire by Carol Siegel, and “So Full of Myself as a Chick: Goth Women, Sexual Independence, and Gender Egalitarianism” by Amy Wilkins interpret goth as a form of sexual liberation which positions sex and gender within a masculine economic order. Such a view misses the subtler and more subversive strategies that formed most of Siouxsie and the Banshees feminism.

The career of Siouxsie and the Banshees was centered on establishing female subjecthood within the punk rock style, expanding the scope of its social criticism to include issues of special relevance to women, and musically depicting gyno–centered traumas that had been ignored by the genre. Ballion and her bandmates recognized that the destructive masculine preoccupation with power, production, and accumulation was the root cause of many of the conditions that gave rise to the punk movement, and therefore shunned masculine gestures of force in favor of conventions that they believed would thwart masculine clarity and positivist logic, but still resonate in both the punk movement and the larger culture of Thatcher’s England.

To achieve these ends Siouxsie and the Banshees drew inspiration from predecessors who reveled in the play of irony and ambiguity, and rejected blues-based notions of authenticity and virtuosity- all conventional musical signifiers of masculine power and production. The group’s visual reliance on signifiers of vamp glamour, and their musical use of Gothicism focused on themes of seduction; a strategy that they usedto critique masculine sensibilities. According to Baudrillard, seduction annuls power and turns the logic of production and accumulation against itself; ideas that he published in 1979, the very same year that Siouxsie and the Banshees began to achieve notoriety. To the knowledge of this author, Susan Ballion has never cited Baudrillard as an influence, but her music expresses similar ideas concerning sex and gender. Rex Butler notes that “Baudrillard’s descriptions are not empirical descriptions which can be evaluated, but a kind of un-demonstrably yet irrefutable doubling of the way things are. The real they speak of and want to reveal cannot be directly pointed to but only alluded to metaphorically” (19). The music and image of Siouxsie and the Banshees can also be understood as a similar type of metaphorical doubling, dramatizing the idea that seduction is more powerful than production. The group would explore this thesis over multiple recordings, and create an oeuvre that remains one of the most powerful feminist statements to appear in pop culture during the 1980s.

Notes

1 One thinks, for example, of how influential scholars such as Julia Kristeva have been dismissive of the expressive possibilities of popular culture in works such as Revolution in Poetic Language, and Desire in Language; Terry Eagleton has never voiced approval of any counter-culture music etc.

2 For a more comprehensive discussion of the punk movement’s relationship to British society see Dick Hebdige Subculture the Meaning of Style, Tricia Henry Break all Rules, and One Chord Wonders by Dave Laing. To better understand what punk culture meant for women see Lucy O’Brien’s The Woman Punk Made Me.

3 Music journalist Mick Mercer explains that during the 1980s, bands were divided into genres based more on the composition of their audience, the subculture with which they were affiliated, and the overriding emotional affect of their oeuvre rather than any distinct technical features of their music. See Mueller The Music of the Goth Subculture page 7.

4 See Charles Mueller “Gothicism and English Goth Music: Notes on the Repertoire.” Gothic Studies. 14/2 November 2012.

5 The late 1970s and early 1980s saw massive labor unrest in England along with crushing unemployment. One could also point to the violence in Northern Ireland and its repercussions in England proper. Europeans lived under the specter of American and Soviet nuclear struggles at that time. Thatcher’s conservatism was based, ironically, on patriarchy and a phallic ideology.

6 The Group did record a camp cover of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” and the track “Peek-a-boo” features oomph-pa-pa figuration that was often used in cabaret numbers. How much of Ballion’s vocal style was shaped by music theater, or torch singers is open to conjecture as it is difficult to pinpoint any clear melodic signatures or vocal techniques from cabaret.

7 For example, “Suburban Relapse” discusses domestic abuse. The masculine roots of war are a central focus of Join Hands. Ballion’s sarcastic reading of the Lord’s Prayer epitomizes the group’s attacks on masculine logic.

8 Susan Ballion notes to Siouxsie and the Banshees, Downside Up (2004), CD, Universal LC6444. The group probably also composed this song as a way to distance themselves from an early controversy where Ballion appeared onstage wearing a Nazi armband strictly for its shock value. Ballion’s faux pas was heavily criticized.

9 Ballion has revealed that she was sexually molested by a neighbor at age nine, and that the rape was ignored by her family. See Paytress, Siouxsie and the Banshees pg. 20.

10 Songs that illustrate how the band used effects like flanger and chorus to turn power chords away from their “truth” as generic signifiers of masculine power include “Overground,” “Jigsaw Feeling,” “Playground Twist,” and “Mirage.”

11 Baudrillard, however, explicitly states that men and women are both equally capable of being masculine/productive or feminine/seductive.

12 In Baudrillard's writing, “cold” or “vulgar” seduction is malevolent, and is about destructive control and possession. “Pure” or “hot” seduction is about making deep, transformative connections.

13 For example, “Hong Kong Garden” mimics the sound of Chinese instruments and folk-melodies, “Candyman” features guitar parts that imitate the sound of a music box, “Staircase Mystery” contains disorientating panning effects, “Carnival” is enhanced by melodies that sound similar to music often heard at fairs, circuses, and in funhouses.

14 Two songs on Peepshow, “The Last Beat of My Heart,” and “Ornaments of Gold” could be considered torch-like love songs, but they are anomalies in the Banshees’s oeuvre.

15 Although a minority of music journalists mistook the band's use of Gothicism as an attempt to revive 1960s psychedelia, the majority understood the Banshees's approach. The group was praised for their ability to vividly capture dark moods both lyrically and musically. New Musical Express critic Roy Carr stated that "if Ingmar Bergman produced records they would sound like this." Steve Sutherland praised the music for its tension and energy but thought that the Banshees use of Gothicism was too superficial, not understanding that the group was trying to shun the logic of production, and masculine notions of depth and authenticity. See NME Originals: Goth volume 1 issue 17.

16 Modulation effects combine the guitar’s original signal with a detuned and delayed copy. Chorus imparts an ethereal lushness to the guitar’s tone, where flangers create a sweeping effect from high to low, smearing the notes and providing a sense of ambient expansiveness.

17 The Raven and A Dream Within a Dream use this technique extensively.

18 Susan Ballion, notes to Siouxsie and the Banshees Downside Up: The Singles (2004), CD, Universal LC6444

19 A Fistful of Dollars, A Few Dollars More and, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly are just a few of the films where the composer used this device.

20 “As the Years Go Passing By,” by Deadric Malone, and “Evenin’” by T-Bone Walker are two examples.

21 Mick Mercer, personal E-mail, 20, April 2005.

22 See Charles Mueller, The Music of the Goth Subculture: Postmodernism and Aesthetics. PhD dissertation, Florida State University 2008.

Bibliography

Baudrillard, Jean. Screened Out. Translated by Chris Turner. New York: Verso, 2002.

———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.

Bracewell, Michael. England is Mine: Pop Life in Albion from Wilde to Goldie. London: Harper Collins, 1998.

Braidotti, Rosi. “The Politics of Ontological Difference.” In Between Feminism and Psychoanalysis, 89-105. Edited by Teresa Brennan. London: Routledge, 1989.

Burns, Lori, and Melissa LeFrance. Disruptive Divas: Feminism, Identity, and Popular Music. New York and London: Routledge, 2001.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity {1990}. New York and London: Routledge, 2008.

Butler, Rex. Jean Baudrillard: The Defense of the Real. London: Sage, 1999.

Dunn, Robert G. Identity Crisis: A Social Critique of Postmodernity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Eagleton, Terry. The Illusions of Postmodernism. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

French, Marilyn.” Is There a Feminist Aesthetic?” In Aesthetics in Feminist Perspective, 68-76. Edited by Hilde Hein and Carolyn Korsmeyer Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Genz, Stéphanie. Postfemininities in Popular Culture. New York: Macmillan, 2009.

Grace, Victoria. Baudrillard’s Challenge: A Feminist Reading. New York and London: Routledge, 2000.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. New York and London: Routledge, 1979.

Kermode, Mark. “The British Censors and Horror Cinema.” In British Horror Cinema, 10-22. Edited by Steve Chibnall and Julian Petley. NewYork and London: Routledge, 2002.

Letts, Don. Punk: Attitude. Freemantle Media, 2005. DVD.

Macarthur, Sally. Feminist Aesthetics in Music. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

Majewski, Lori, and Jonathan Bernstein. Mad World: An Oral History of New WaveArtists and the Songs that Defined the 1980s. New York: Abrams, 14.

McRobbie, Angela, and Jenny Garber. “Girls and Subcultures,” in The Subcultures Reader, edited by Ken Gelder and Sarah Thornton (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), 112-120.

Moore, John. “The Hieroglyphics of Love: The Torch Singer and Interpretation.” In Reading Pop: Essays in Textual Analysis, 262-96. Edited by Richard Middleton. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Moore, Suzanne. “Getting a Bit of Other: The Pimps of Postmodernism.” In Male Order: Unwrapping Masculinity, 165-93. Edited by Rowena Chapman and Jonathon Rutherford. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1988.

Morley, Paul. “This is Siouxsie and the Banshees.” New Musical Express, January 1978, 7.

Paytress, Mark. Siouxsie and the Banshees: The Authorized Biography. London: Sanctuary, 2003.

Plant, Sadie. “Baudrillard's Woman: The Eve of Seduction.” In Forget Baudrillard? 88-106. Edited by Chris Rojek and Bryan Turner. London: Routledge, 2003.

Petley, Julian: “A Crude Sort of Entertainment for a Crude Sort of Audience: The British Critics and Horror Cinema.” In British Horror Cinema. Edited by Steve Chibnall and Julian Petley, 24-67. New York and London: Routledge, 2002.

Punk: The Early Years {1978}. Pottstown PA: MVD Visual, 2003. DVD.

Reynolds, Simon, and Joy Press. The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion, and Rock “n” Roll. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Roberts, Chris. Review of Siouxsie and the Banshees “Peepshow,” Melody Maker, September 1988, 37.

Siegel, Carol. Goth’s Dark Empire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Thompson, Dave. The Dark Reign of Gothic Rock. London: Helter Skelter, 2002.

Walser, Robert. Running with the Devil: Power Gender and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1993.

Whiteley, Shelia. Women and Popular Music: Sexuality, Identity, and Subjectivity. New York and London: Routledge, 2000.

Wilkins, Amy C. “So Full of Myself as a Chick: Goth Women, Sexual Independence, and Gender Egalitarianism.” In The Politics of Women’s Bodies: Sexuality, Appearance and Behavior. Edited by Rose Weitz, 163- New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Willsher, James Ed. The Dedalus Book of English Decadence. Cambs: Dedalus, 2004.

Select Discography

Siouxsie and the Banshees, Downside Up, 2004, Universal, 4 compact discs. Recorded 1978-1995.

———. Hyaena, 1984, Geffen. compact disc.

———. A Kiss in the Dreamhouse, 1982, Polydor, 331/3 rpm.

———. Once Upon A Time/The Singles, 1981, Geffen (US)/Polydor (UK), 331/3 rpm.

———. The Scream, 1978, Polydor, 331/3 rpm.

———. Tinderbox, 1986, Geffen, compact disc.

Video Recording

Siouxsie and the Banshees. Nocturne (Burbank, CA: Universal Music, 2006), DVD.