Abstract

Undergraduate music programs are currently reexamining the place and value of theory study. While some have argued for this core subject to be dissolved and absorbed by related courses, others defend that music theory is a non-negotiable core of musicianship and not specialized enough. Amidst the scholarly debate over the curricular needs of the 21st century musician-in-training, the voice of students themselves are regularly treated tangentially, if not dismissed. As such, when it comes to understanding the student experience, many educators remain in the dark. How has theory class contributed to the professional lives of recent music program graduates? What aspects of theory class are seen to be the most beneficial, and the most confounding? How do students view the relationship between what is assessed and what is most personally useful? To shine some light on these questions a detailed online survey was conducted via the social media website Reddit.com, targeting recent graduates of music programs. Despite the diverse musical backgrounds of respondents (n=291), results show significant agreement in student views toward their theory experience. Generally, results affirm that (1) music majors tend to view music theory as a highly valuable subject of study, and (2) there are significant trends in what students identify as areas for improvement. Specifically, students complaints revolved around three issues: integration, diversity, and creativity. The analysis presented in this paper opens a powerful window to the student perspective, offers curricular recommendations, and discusses the advantages and limitations of Reddit as a recruitment source.

Introduction

In early 2017 Harvard’s music department chose to dispense with the introductory music theory requirement for music majors, prompting music educators everywhere to pause, reflect, and revisit a perennial question––what is the real value of theory study for students today? Shifts such as Harvard’s have sparked a flurry of debate within academic circles, music education advocacy groups, authors and bloggers alike. Concerns gravitate toward familiar camps: traditional concerns (preserving musical literacy and the classical canon), ethical concerns (building social equity, dismantling cultural hegemony and orthodoxy) and pragmatic concerns (developing skills and competency, careers and entrepreneurship). Yet, one collective voice has been glaringly absent from this multilogue: that of the students themselves. This void is especially odd considering the centrality of the student in the first music conservatories. These institutions did not begin as conservers of musical traditions and practices, but were founded in orphanages with the charge of preserving the very lives of their students, who themselves were the conservati.

It needs to be asked, then, how do students today see the value of theory study? Are students really learning what instructors think they are teaching? How did it benefit them and contribute to their overall musical experience? How did theory study help or hinder their musicianship, creative practice, career? For addressing these questions students become the foremost experts, yet student feedback is routinely devalued as a legitimate source of critique of curriculum or teaching practice. Aside from course evaluations and online professor rating websites, there exists no avenue or forum for students to respond to their learning experience in a way that might inform curricular decision-making.

To gain a better understanding of student perspectives regarding the character and value of college theory, a detailed online survey was created to allow former students to respond to their undergraduate theory experience. The survey aimed to (1) Evaluate student sentiment toward their experience of music theory study, (2) Determine what students see as the greatest benefits and shortcomings of theory class, and (3) Draw correlations between these perspectives and students’ primary major and instrument. The survey included seven multiple choice questions, thirty Likert scale questions, and an open comment question. It was distributed via the social media website Reddit.com, targeting graduates of college music programs through various discussion community groups (subreddits).

Respondents (n=291) provided valuable insights into the strengths and weaknesses of music theory pedagogy from the student perspective. Analysis of the results reveal two major trends. First, that former music majors tend to view theory study as highly valuable, particularly aural and analytical skills, and engaging creatively with course material. Second, there is strong agreement among students regarding the shortcomings of theory class. Specifically, three areas of primary concern were identified: integration, diversity, and creativity. This paper presents and analyzes these results, makes curricular recommendations, and discusses the advantages and limitations of Reddit as a recruitment source.

The findings sound from the voices at the center of the current struggle for college theory to identify itself. Before presenting results, it is important to examine the background of the current situation in the context of a prior ‘crises’ faced by college theory teaching.

Background: Crises in Theory Teaching

In March, 2017, The Harvard Crimson1Leifer, “Music Department to Adopt New Curriculum Beginning Fall 2017" reported that the Department of Music at Harvard University will eliminate introductory music theory and music history courses from its core requirements for music majors (a.k.a. “concentrators”). These requirements are to be replaced by courses on “Thinking About Music” and “Critical Listening” for students who elect to follow a custom course load rather than the traditional pathway. In response, a social media buzz erupted as scholars, educators, and artists around the globe blogged, tweeted, and published editorials of both praise and reproach. Is this a harbinger of coming trends about to sweep through music higher education? Harvard’s move is in step with the broader conversation surrounding the place of traditional music education in institutions that champion multiculturalism.

For example, recent meetings of the American Musicological Society have held musical privilege walks, group exercises designed to “allow music professors to understand their own privilege (or lack thereof) and that of their students.”2Leonard, “Music Privilege Walk Statements" Participants would step forward or backward as directed by a series of fifty statements–– “If your parents/guardians could pay for your instrument or you had use of a free school instrument, step forward,” “If you had to work instead of practice, step backwards,” “If you owned a metronome, tuner, music stand, instrument cleaning supplies, and method books (in your language), step forward.” Any history of participation in a conventional music education, in this exercise, is a representative of privilege. Suffice to say, there are those who oppose such a negative characterization of music education, especially as so many schools fight to keep a music program at all. One group has begun collecting signatures3Pace, “Risky romanticization of musical illiteracy,” 32. in an outright stand against the “romanticization of musical illiteracy” and the anti-intellectualism they feel is at its core.

With the rise of such division it is impossible for a theory teacher not to feel unsettled, and indeed they should feel unsettled. The ground is shifting beneath their feet, just as it has for math and science teachers in recent years. Harvard’s change itself is an echo of Wayne State’s 2016 decision to substitute its general mathematics requirement4Students at Wayne State University no longer have to take a single math course to graduate, and may soon be required to take a diversity course, instead.” Jesse, “Wayne State drops math as general ed requirement.” with a diversity class. The quest for social justice calls all scholars to reevaluate the basic assumptions that uphold their domains of expertise, and for teachers to reconsider how their courses contribute to (or obstruct) a more equitable world. These conversations are difficult and necessary, and the outcomes will lay the foundation for education for years to come.

As for music theory teaching, over the centuries, paradigm-shattering crises are more or less par for the course. The idea that Nature supported the rules of harmony, questioned by Helmholtz from the scientist’s point of view, collapsed completely with the beginning of twentieth century music. In 1965 the Journal of the College Music Society posed the following question in a special issue entitled “The Crisis in Theory Teaching:” “In view of the great advances made in recent years in composition, do you think that ‘traditional’ harmony, counterpoint, etc., are still essential to the training of a music student? Or do you feel that these courses are outmoded and need to be replaced with new curricular concepts?” A trifecta of American composers responded: Milton Babbitt, Howard Boatwright, and Andrew Imbrie. Each framed the ‘crisis’ and its solutions through the lenses of their respective compositional schools of thought, each presented a unique conception of what music theory is, and a clear vision of what it should be.

In their responses it was clear that Babbitt, Boatwright, and Imbrie, though addressing the same prompt, were perceiving three entirely different crises. For Babbitt, at the center of crisis was the failure of music “theory” to live up to the rigorous standards set by scientific theory, and he called on theorists to be primarily concerned with making and testing predictions. For Boatwright, theory teaching collapsed from a neglect of history, and called for an “unbiased exposure to the full range of tonally organized music.” For Imbrie, “theory” was a “strange term to apply to a discipline designed to develop a student’s mastery of a craft,” that “One doesn’t learn to swim by studying the theory of swimming.” Imbrie finds the principal value of theory teaching to be the development of a student’s own artistic independence and autonomy. Even though these three approaches were, in part, a product of the larger academic iconoclasm of the 1960’s, they can also be seen as reiterations of early paradigms forwarded by theorists Rameau, Forkel, and Fux (Dunsby, 2010). They also represent what Carl Dahlhaus identifies as the analytical, regulative, and speculative tradition of music theory (Dahlhaus, 1990).

Somewhat appropriately, this crisis surfaced at a mid-point between the present day and Helmholtz’ attempt to emancipate music theory from “speculative dreaming” in 1875.5Helmholtz, “On the Sensations of Tone: As the Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music,” 347. And now, Harvard has committed to a new direction. This change aligns with the most provocative and progressive call for educational change in recent years: the Manifesto for Change, the College Music Society report from the Task Force for the Undergraduate Music Major (Campbell, 2014). This report aims to “break the logjam” of previous attempts at curricular reform that were merely “masquerading as genuine change.”6Ibid., 59. Harvard’s action just may be an early indication that the logjam has begun to loosen, though it’s not the only one. The Frost School of Music at the University of Miami has been experimenting with a curriculum that threads theory, history, ear training and performance in one fully-integrated curricular design. Judy Lochhead’s recent book Reconceiving Structure in Contemporary Music: New Tools in Music Theory and Analysis highlights how the emphasis on the music of the Western canon is coupled with a “near-automatic rejection of recently created music,”7Lochhead, Reconceiving Structure in Contemporary Music, 2. and presents dynamic approaches for productive theoretical engagement with the sounds of the present. Improvisation and Music Education presents the efforts of current educators to reclaim once-integral skills lost to recent pedagogical traditions: improvisation, creating without the aid of notation, entrepreneurship, and post-genre musicianship (Heble, 2016).

Higher educators are also desperately trying to adapt to a student body of digital natives. The emerging approaches described above are united by a common goal: to guide students to critically engage with and enact the music that represents the world we inhabit today. Lochhead highlights that while creators of new music, artists such as Kaija Saariaho, Stacy Garrop and Anna Clyne, have been reconciling the structures of musical time, the curricular engagement with this recent music has not kept pace.8Lochhead, 3. Educators can hardly be blamed. Music exists in the present, in the lived world through the broad range of embodied human action and experience, but a lengthy process of production and distribution has traditionally given educators a buffer to make keeping pace plausible. Students today are intimately acquainted with musical trends, the distribution mediums, the production technology, and the social networks out of which new music emerges daily. Yet, music majors still look to faculty to help them be innovators by filling in the skill and knowledge gaps, to broaden their perspective, to teach them what they cannot find in a discussion board, MOOC, or free online tutorial. Because little is known about the needs of this new type of student, it is increasingly questionable that educators are sufficiently equipped to meet this new wave. Yet, the tide advances.

The Need for Student Feedback

To be properly equipped to meet this new student body, educators need more student input, not less. While students routinely evaluate courses at the end of each term, and many institutions conduct general student satisfaction surveys, these are severely limited in terms of the substantive impact. Course evaluations largely function to gauge instructor effectiveness, while surveys of student satisfaction function exclusively for the interests of the particular institution. For most universities in the U.S. these represent the only systematized forums in which students can provide feedback for their higher education.

While there exists growing doubt that student evaluations measure what they claim to measure (Braga, et al.; MacNell, et al.), the issue of student feedback is neither a student problem nor an instructor problem; it is a measurement problem. Instructors are only one part of the educational machine. To students, however, instructors necessarily become its face. Student complaints about a course or professor are often the synthesis of a number of frustrations, many beyond the sphere of the individual instructor. A student may take legitimate issue with poor curricular design, a negative classroom climate, a lack of integration between core subjects, a disconnect between learned material to long-term goals, an unfavorable effort-outcome ratio, among many other factors. However, these factors are categorically absent from student evaluations. This absence signals to students that individual instructors are ultimately on the hook for any level of dissatisfaction. While the instructor might have little or no power in determining many aspects of what is taught, such as the learning outcomes of the theory core, they remain the only entity available for students’ critique.

Without student feedback there is no metric for music programs to evaluate reliably the student perspective of the learning experience. Instructors, administrators, curricular experts, textbook authors, etc. are not equipped to measure the relevance of curricular material to the environment students are preparing to enter. The debate over how or if music theory in higher education is to change might progress more swiftly if it included the voices of those it understands itself to be serving: the students.

Reddit as a Recruitment Source

Surveying music students from across the U.S. is now a manageable task thanks to social media platforms, which make targeted polling a faster, more reliable, and more economical process than ever before. This section will discuss why the website Reddit is an ideal source for recruiting the specialized participants needed for this study.

While initially skeptical, scientific studies are increasingly relying on online recruiting for surveys. The volume and immediacy of web-based information has made crowdsourcing a powerful tool for researchers across many domains. Sample populations can be targeted, contacted, and polled with incredible speed. Several analyses9Woo, Kim, & Couper, 2015; Wilson & Dewaele, 2010; Birnbaum, 2004; Evans & Mathur, 2005; Miller & Dickson, 2001; Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2000. demonstrate that surveys conducted over the internet provide results that are at least as valid as traditional methods. The same concerns that underlie all surveys still apply– including high dropout rates, repeated participation, and insincere responding.

Social media dramatically inflates in the ease of participating in broader cultural discussion, which, in turn, makes the discussion more vulnerable to questionable information. Simply put, the added convenience proportionately devalues the conversation. A prime example of this was seen in 2016 when the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council invited the public to help in naming their new, state-of-the-art ocean research vessel via their #NameOurShip Twitter® campaign. To the council’s surprise, the winning name was Boaty McBoatface. With over 27,000 votes this was the public’s choice by a significant margin.10Olivennes, “Boaty McBoatface, From Internet Joke to Polar Explorer” The benefit of speedy, targeted recruitment that makes crowdsourcing so valuable becomes its liability. Increased convenience in recruitment thus may carry the cost of lower reliability and quality.

Yet, not all social media platforms are equal. Platforms (i.e. Reddit, Wikipedia, Twitter, Facebook etc.) structure web communities differently, each centralizing a different aspect of social interaction. Reddit (which calls itself “the front page of the internet”) is a social media website that centralizes the discussion of news and events, stories, and shared links. Users can join existing special interest subforums, called ‘‘subreddits,” which cover an ever-expanding array of topics, or create their own subreddit. Community discussion is regulated through members rating the quality of submitted content with upvotes and downvotes. These votes affect a post’s visibility to the rest of the community. This provides a form of community-based moderation, where content with more positive votes is significantly more visible.

Reddit’s community structure is unique in centralizing the discussion of information, distinguishing it from Wikipedia–where users largely assume the validity of the content as presented and any discussion takes place behind the scenes, from Twitter–which centralizes the contagion of information but makes discussion virtually impossible, and from Facebook–where discussion of any topic remains exclusive to the immediate friend group. One recent series of experiments at George Mason University through a course titled Lying About the Past11Applebaum, “How the Professor Who Fooled Wikipedia Got Caught by Reddit.” In these experiments Redditors successfully weeded out fabricated news stories within minutes, while Wikipedia failed to identify any. Reddit succeeded due to the community structure and the incentive system (upvotes) that biases users toward more accurate information. demonstrates that Reddit’s unique structure incentivizes accuracy of information. Subreddits can form freely around any topic, no matter how broad or narrow, and members of these communities share a vested interest in the quality of their shared information. This structure is what sets Reddit apart from other online platforms. Of course the ultimate accuracy of information exchanged in Reddit is by no means a given, only the presence of a discussion incentivized toward accuracy, as negotiated by the community members.

Thus, Reddit not only allows for free and rapid recruitment of large survey sample sizes, it is optimized for the targeting of specific groups whose members exhibit a bias toward the exchange of more accurate information than other social media platforms. Reddit averaged 1.2 billion visits per month between September 2016 and February 2017, and ranks sixth in the world among social media websites by that measure. A 2016 study of the demographics of adult U.S. Reddit users (approximately half of the active users on the site) showed that they are roughly representative of the demographics of the general adult U.S. population, particularly when controlling for age (Barthel, 2016). Some key differences that work in favor of this study are that 90% of users are under age 35, and users are more educated than the general population (36% of users hold a college degree, compared with 28% generally). A follow-up study (Shatz, 2016) which compared three previous studies of Reddit demographics concludes that the Reddit sample populations, overall, are as viable as samples recruited by more traditional means (mail, email, survey agency).

For four reasons Reddit is an ideal source for recruiting participants for this: (1) specific subreddits related to music theory, music education, music majors, etc. can be targeted specifically, (2) a large sample size is accessible in a short time span, (3) Reddit communities have been shown to be as reliable as traditional samples, and exhibit a bias for toward accurate exchange of information due to Reddit’s community structure, and (4) studies can be conducted for free, as users generally have an interest in participating without monetary incentive, largely due to the preexisting buy-in with their subreddit community.

Methodology

This section follows the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (Eysenbach, 2004).

To address the need for the student voice in conceptualizing the role of music theory in today’s music programs, this open survey targeted current or former undergraduate music majors who had completed the music theory core curriculum required by their major. The study had three central research questions:

(1) What is the general sentiment toward the experience of music theory study among students?

(2) What do students see as the greatest benefits and shortcomings of theory class?

(3) Is there a relationship between students’ primary major and/or instrument and questions 1 and 2?

The researcher used the web service SurveyMonkey™ (n.d.) to design the survey, generate a hyperlink, and collect responses. The hyperlink was posted on several Reddit.com© sub-reddit communities most likely to contain users (a.k.a “Redditors”) from the target population: r/musictheory, r/MusicEd, r/MajoringInMusic, r/Music_Theory_Class, r/music, r/classicalmusic, r/musicians, and r/WeAreTheMusicMakers (“r/name” nomenclature is standard shorthand for identifying reddit communities). The number of users subscribed to each of these communities varied greatly, from 4,550 (r/MusicEd), to 75,738 (r/musictheory), to over 15 million (r/music). The hyperlink was posted to the message boards of each subreddit. As subscribers to these subreddits, users are able to view community content, post, comment, and discuss content with other sub-redditors. On Reddit all involvement is voluntary, and generally only a small percentage of each community views each post. It is not possible to know how many Redditors viewed the invitation to participate in the survey, and therefore impossible to determine an accurate response rate.

Respondents were told the length of time for completion of the survey (5 minutes), the academic affiliation of the researcher (University of California), the purpose of the survey, and that no personal information would be collected. No incentives were offered. The survey remained open from June 2016, to February 2017. Once submitted, respondents were unable to alter any of their answers.

The survey consisted of ten questions. The first section included seven multiple choice questions, which all included an “Other” option. The next two questions were Likert-style on a five-point scale. The first had eleven parts, the second had nineteen parts. The final question was an open comment question. Please refer to the Appendix for the full survey format. All questions were displayed on a single page. All multiple choice questions included an “Other” option, and all questions could be skipped voluntarily. The average skip rate was 2%, and all responses were included in the final analysis. The host site uses browser cookies to assign a unique user identifier to each respondent to prevent multiple responses from a single user. No IP addresses were restricted from participating. Aside from specifying music major emphasis and principal instrument, no identifying questions were asked. Socio-demographic questions (e.g. race, gender, etc.), although of interest, were omitted in order to minimize the length of time it would take to complete the survey, an important factor in attracting and retaining respondents. Another argument for the omission of these questions is the “stereotype threat,” i.e., that respondents’ answers might change if they know that their socio-demographics are being taken into account. The “stereotype threat” is defined as the “experience of anxiety or concern in a situation where a person has the potential to confirm a negative stereotype about their social group.”12Gilovich (et al.), Social Psychology, 467–468.

After collecting the questionnaire responses, the survey was closed, and the researcher analyzed the data by calculating correlations and by coding open-ended responses and identifying emergent categories. This was done through content analysis, which involved the simultaneous construction of categories that capture relevant characteristics.13Merriam, Qualitative Research.

Results

Who

The survey fielded a total of 291 respondents from various Reddit.com subreddits. Question 1 asked respondents to specify the emphasis of their music major. The majority (81%) of respondents to this question (who did not choose “Other”) were either instrument performance majors, music education majors, or composition majors. Thirty-nine respondents skipped this question, and fifty-three specified an “Other” undergraduate major.14”Other” majors included more specific music emphases: music history, jazz studies, computer music, science of music, musicology, ethnomusicology, music industry studies, music technology, jazz and pop music, pre-music therapy, music therapy; as well as non-music majors who either double majored or minored in music: computer science, law, neuroscience, physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, linguistics, psychology, engineering, accounting, and liberal arts.

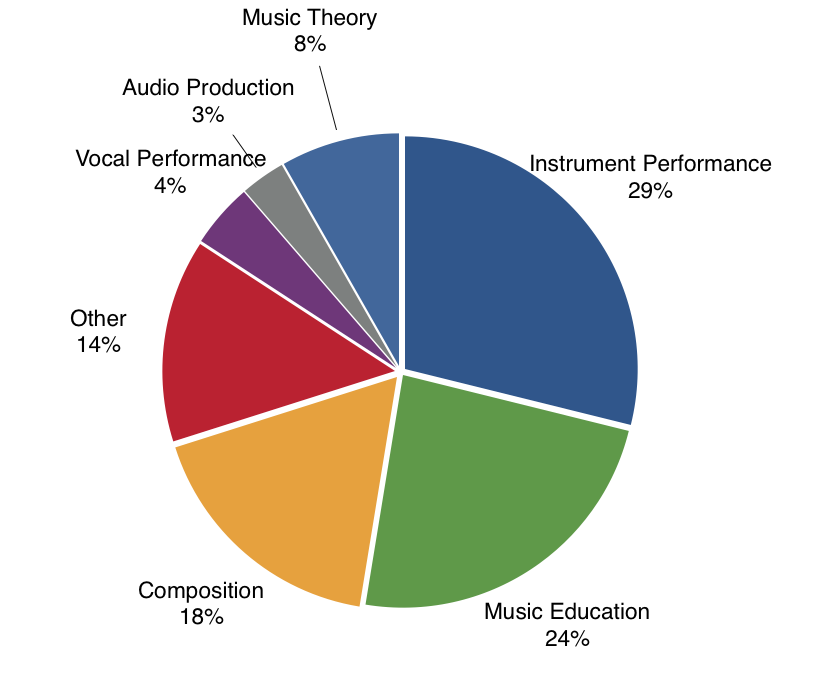

Figure 1.1:

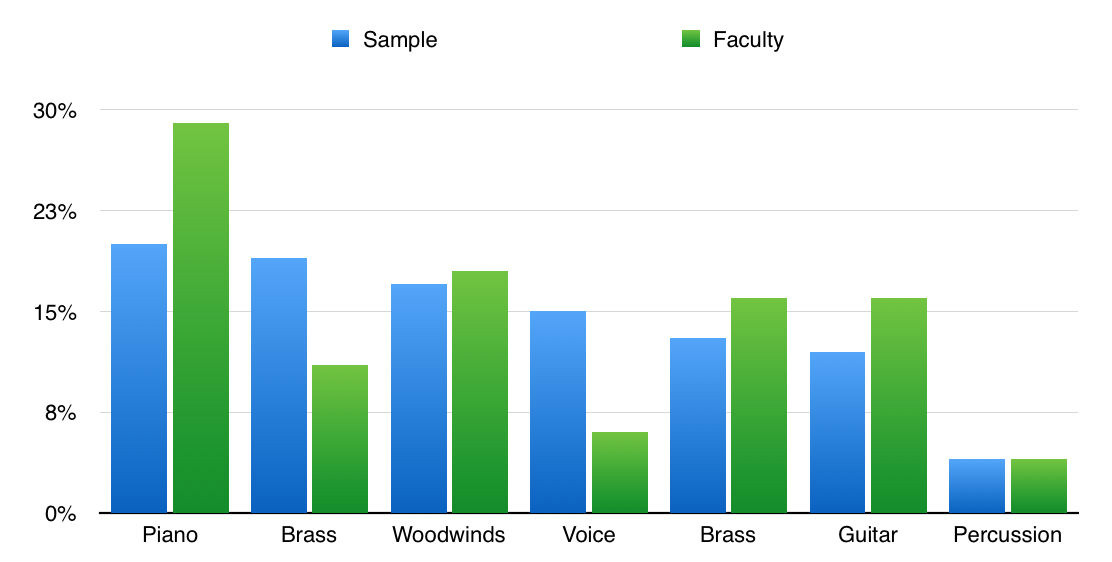

Respondents specified their primary instrument in question 2. No statistical record exists regarding the principal instruments of undergraduate music students in order to compare the survey sample with a baseline. However, when looking at the Directory of Music Faculties in North America15Directory of Music Faculties in Colleges and Universities, U.S. and Canada. 2016-2017. we can see that the survey sample and the instrument faculty population correlate reasonably well.

Respondents specified their primary instrument in question 2. No statistical record exists regarding the principal instruments of undergraduate music students in order to compare the survey sample with a baseline. However, when looking at the Directory of Music Faculties in North America15Directory of Music Faculties in Colleges and Universities, U.S. and Canada. 2016-2017. we can see that the survey sample and the instrument faculty population correlate reasonably well.

Figure 1.2:

Assuming that faculty presence represents an index of student demand, the principle instrument population of students in North America should follow proportionately. Differences between instructors and the survey sample can partly be explained by common overlap in instructor roles (i.e. some faculty teach piano although it is not their primary instrument) or by ambiguous terminology (some bass students might choose “Guitar” if they associate more closely with the bass guitar than the contrabass).

Assuming that faculty presence represents an index of student demand, the principle instrument population of students in North America should follow proportionately. Differences between instructors and the survey sample can partly be explained by common overlap in instructor roles (i.e. some faculty teach piano although it is not their primary instrument) or by ambiguous terminology (some bass students might choose “Guitar” if they associate more closely with the bass guitar than the contrabass).

Evaluating Student Sentiment toward Music Theory

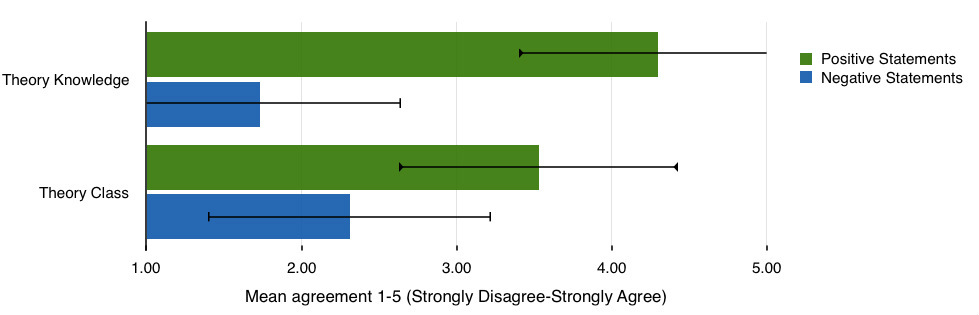

The first objective of this survey was to determine student sentiment toward their experience of music theory. The general sentiment reported by the sample population was very positive, as shown through a series of Likert scale questions. It is important to distinguish student perceptions of their theory classes (evaluations of curriculum, instructor, assessment, etc.) from their perceptions of the value of theory knowledge (the utility of understanding, relevance to their goals, contribution to their career, etc.). To do this, to the extent that it is possible, two complete-the-sentence prompts were posed–– Question 8: “Music theory knowledge...”, and Question 9: “My music theory class...”, each followed by a series of statements to be disagreed with or agreed with on a five-point Likert scale. No statement presented a forced choice, as “Neither” was always an option.

The prompt “Music theory knowledge...” (n=290, 1 skipped) was followed by a random mix of 11 positive and negative statements about music theory. A positive statement is one for which agreement is a positive evaluation (e.g. “Music theory knowledge...has helped me better understand the music I perform”) while a negative statement is one for which agreement is a negative evaluation (e.g. “Music theory knowledge...does not apply to my personal musical goals”). Overall respondents more than ‘Agreed’ with all positive statements ( = 4.30, s = 0.9), and more than ‘Disagreed’ with negative statements ( = 1.73, s = 0.91). Four of the eleven statements had the maximum median response of 5 (Strongly Agree): “...has helped me better understand the music I perform” ( = 4.53, s = 0.77), “...has improved my experience of classical music” ( = 4.39, s = 0.84), “...is very beneficial to me” ( = 4.36, s = 0.85), and “...has had a positive effect on my creativity in music” ( = 4.23, s = 0.99). For theory teachers, the most encouraging result from this survey might be that only 3.8% of respondents disagreed that theory is “very beneficial.” Amidst this very positive sentiment toward theory knowledge, however, enthusiasm for “improved career prospects” was noticeably curtailed in comparison ( = 3.84, s = 1.12).

The prompt “My music theory class...” (n=290, 1 skipped) was followed by positive, negative, and neutral statements in random order. For positive statements (e.g. “My music theory class...had clear assessment expectations”) respondents were overall between agreement and neutrality ( = 3.53, s = 1.09), while negative statements (e.g. “My music theory class...is boring”) showed benign overall disagreement ( = 2.31, s = 1.00). The only statement to result in an extreme median (either 1 or 5) was “...is not relevant” ( = 1.61, s = 0.94), indicating that despite disagreement over the value of specific aspects of theory courses, respondents overall regard music theory class as highly relevant. Although sentiment was generally positive, when comparing student sentiment between theory knowledge and theory classes, a significant drop-off in positivity can be observed.

Figure 2:

Self-selection bias arises in any situation in which individuals select themselves into a group, which makes it difficult to determine causation. In this case, any number or combination of factors could have compelled Redditors to respond to this survey that would render this sample unrepresentative of an unbiased cross section of the target population: preexisting favorable or unfavorable sentiment toward their music theory experience, higher-than average interest in contemporary issues of education, the age and relative expendability of time in order to participate in a survey, and the demographic characteristics of Redditors generally. These are just a few important considerations. Some of the survey questions attempt to control for these and other factors. However the larger aim of this study, beyond surveying student evaluations of music theory ex postfacto, is to find evidence for overlap between the aspirations of contemporary scholarship in music curricula and those of the students themselves.

Self-selection bias arises in any situation in which individuals select themselves into a group, which makes it difficult to determine causation. In this case, any number or combination of factors could have compelled Redditors to respond to this survey that would render this sample unrepresentative of an unbiased cross section of the target population: preexisting favorable or unfavorable sentiment toward their music theory experience, higher-than average interest in contemporary issues of education, the age and relative expendability of time in order to participate in a survey, and the demographic characteristics of Redditors generally. These are just a few important considerations. Some of the survey questions attempt to control for these and other factors. However the larger aim of this study, beyond surveying student evaluations of music theory ex postfacto, is to find evidence for overlap between the aspirations of contemporary scholarship in music curricula and those of the students themselves.

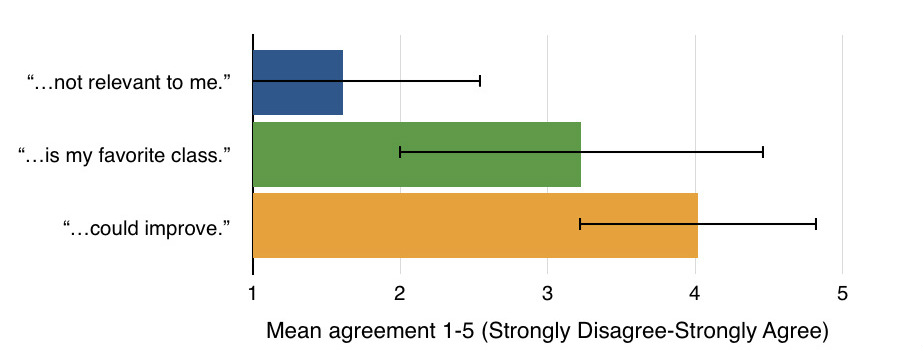

To help gauge the effect of self-selection bias the statement “Music theory class...is my favorite class” was posed. The median response was 3 ( = 3.29, s = 1.24), indicating that the sampled population skewed only slightly toward a positive bias, but not significantly. Still, this presence of bias should be taken into account when interpreting the general positivity of the results.

The optional open-ended comments submitted by respondents tell a different story, however. In total, negative comments outnumbered positive comments 93 - 29, with 12 neutral comments. A more detailed analysis of these valuable comments is presented below.

Perceived Shortcomings of Theory Class

Despite such positive sentiment, 236 (81%) of respondents agreed with the statement “Music theory class...can be improved” ( = 4.02, s = 0.81), which was the highest mean and lowest standard deviation of any other statement for question 9.

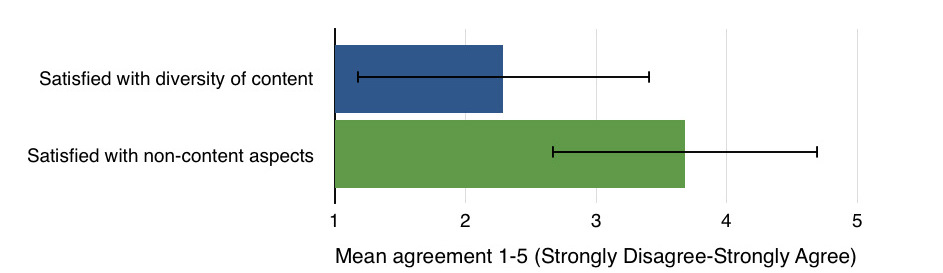

Figure 3.1:

So what do students generally report to be the major shortcomings of their music theory classes? While scholars debate about which topics theory curricula do not address sufficiently, such as improvisation and physics of sound, question 9 sought to measure the degree to which students agreed with these content-related concerns. Four “sufficiently discusses” statements (e.g. “My music theory class...sufficiently discusses...) were presented, followed by domains frequently cited as lacking in the curriculum: improvisation, cultural diversity, physics of sound, and music psychology/cognition. Overall responses indicate insufficient discussion of all of these topics in their classes (m = 2, = 2.29), with improvisation considered the most insufficiently discussed (= 2.06). Comparatively, student attitudes toward non-content aspects appear positive, albeit benignly. These include “My music theory class is clear about its–” “–assessment expectations” ( = 3.94), “–purpose for me as a musician” ( = 3.69), “–relationship with other core subjects” ( = 3.69), and “relevance for my instrument” ( = 3.40).

So what do students generally report to be the major shortcomings of their music theory classes? While scholars debate about which topics theory curricula do not address sufficiently, such as improvisation and physics of sound, question 9 sought to measure the degree to which students agreed with these content-related concerns. Four “sufficiently discusses” statements (e.g. “My music theory class...sufficiently discusses...) were presented, followed by domains frequently cited as lacking in the curriculum: improvisation, cultural diversity, physics of sound, and music psychology/cognition. Overall responses indicate insufficient discussion of all of these topics in their classes (m = 2, = 2.29), with improvisation considered the most insufficiently discussed (= 2.06). Comparatively, student attitudes toward non-content aspects appear positive, albeit benignly. These include “My music theory class is clear about its–” “–assessment expectations” ( = 3.94), “–purpose for me as a musician” ( = 3.69), “–relationship with other core subjects” ( = 3.69), and “relevance for my instrument” ( = 3.40).

Figure 3.2:

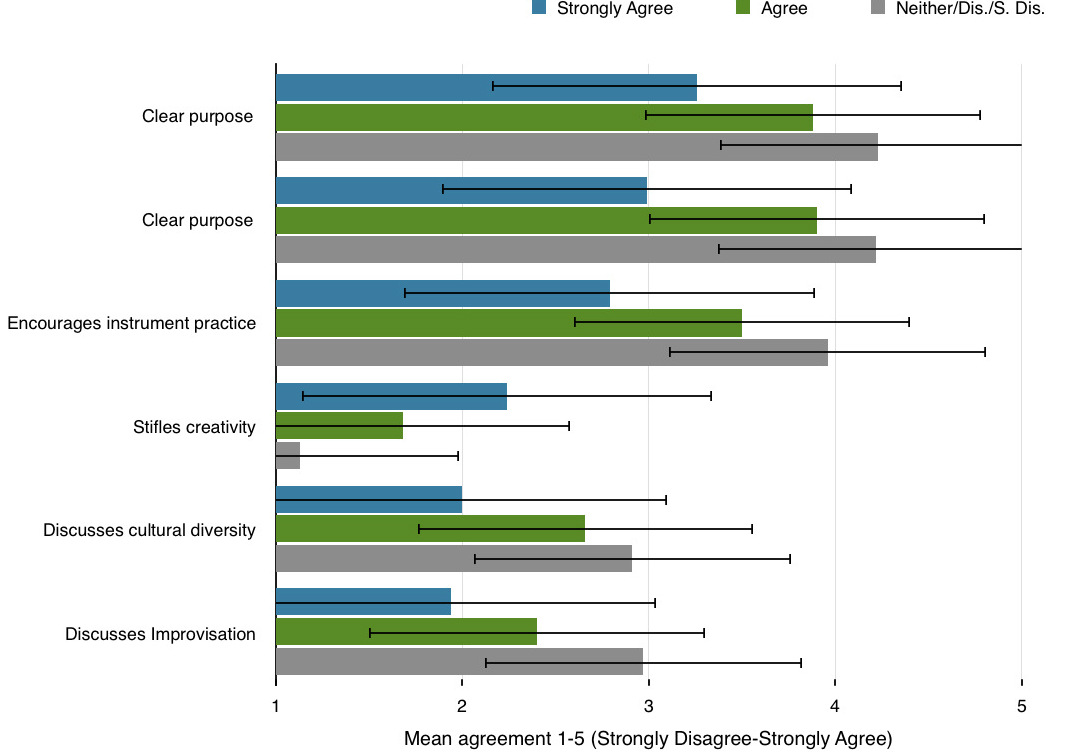

Of the 233 respondents who agreed that theory class could be improved, 78 (1/3) “Strongly Agreed.” In statistical analyses of Likert scale responses “Agree” (A) and “Strongly Agree” (SA) are generally treated as different by degree, not kind. In this case, given the generally positive evaluations, comparing how these A and SA respondents differed in their other evaluations helps to zero in on areas most in need of improvement, as rated by the most concerned among students. These SA respondents were highly correlated with more negative evaluations of theory knowledge and theory class across the board when compared to the A respondents (r =.435, p < .01). A and SA respondents differed by more than 1/2 a standard deviation on six out of twenty-seven statements presented in questions eight and nine. When comparing these to the other 19% of respondents (those who Disagreed/Neither that theory class can be improved) a clearer image emerges of what students see as areas most in need of improvement.

Of the 233 respondents who agreed that theory class could be improved, 78 (1/3) “Strongly Agreed.” In statistical analyses of Likert scale responses “Agree” (A) and “Strongly Agree” (SA) are generally treated as different by degree, not kind. In this case, given the generally positive evaluations, comparing how these A and SA respondents differed in their other evaluations helps to zero in on areas most in need of improvement, as rated by the most concerned among students. These SA respondents were highly correlated with more negative evaluations of theory knowledge and theory class across the board when compared to the A respondents (r =.435, p < .01). A and SA respondents differed by more than 1/2 a standard deviation on six out of twenty-seven statements presented in questions eight and nine. When comparing these to the other 19% of respondents (those who Disagreed/Neither that theory class can be improved) a clearer image emerges of what students see as areas most in need of improvement.

Figure 3.3:

These six statements can be pooled into three areas of general concern: integration (integration with other courses, clarity of purpose, instrument focus), diversity, and creativity/improvisation.

These six statements can be pooled into three areas of general concern: integration (integration with other courses, clarity of purpose, instrument focus), diversity, and creativity/improvisation.

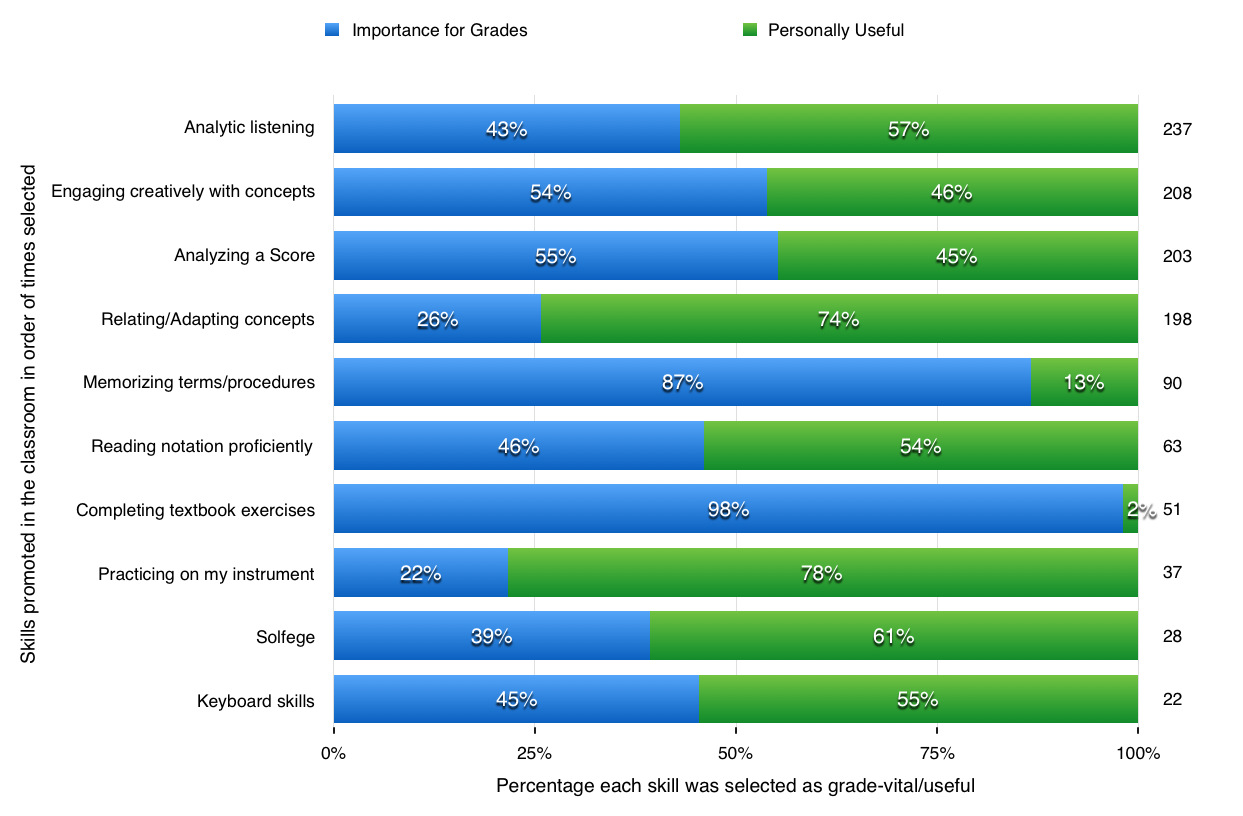

Skills: Grades versus Utility

Students perceive some difference between skills needed to earn a good grade in theory class and skills that are personally useful. Survey questions 4-7 were multiple choice and asked students to specify which skill promoted in the classroom was the (1) most/second most vital for attaining a high grade, and (2) most/second most personally useful. Of the ten skills/activities listed,16Completing textbook exercises; analytic listening; practicing on my instrument; engaging creatively with concepts; memorizing terms, rules, and procedures; analyzing a score; solfeggi/hand-signing; reading notation proficiently; relating/adapting concepts to my personal musical goals; keyboard skills. “Analyzing a Score” (20.4%, n=279) was the most vital skill for attaining a high grade, while “Relating/adapting concepts to goals” (35.5%, n=287) was the most useful skill promoted in the classroom. The skill that was rated most highly across both categories was “Engaging creatively with concepts.” 14% of respondents chose “Memorizing Terms and Rules/Procedures” as either the most or second most vital skill for attaining a high grade. However, only 2.1% of respondents indicated it as useful. Similarly, 9% of respondents regarded “Completing textbook exercises” as the most or second most vital skill for attaining high grades, but only 1 respondent (.004%) regarded it as useful. These differences could be slightly deceptive, as it could be argued that “Relating/adapting concepts to goals” is only possible, to some degree, through the memorization of terms and procedures and working through textbook exercises.

All ten options are generally considered important aspects of theory teaching. In curricular terms, skills vital for grades and skills that are the most useful might represent assessment categories and performance objectives.17In this case, performance objectives are equated with student perceptions of usefulness. This framing privileges practical objectives over those that might be less “useful,” but still valuable, such as speculative theory or analysis for understanding and appreciation. Theoretically, these should be in alignment. However, as previously discussed, the struggle to define “performance objectives” in music theory has perennially been at the center of many of its crises. By comparing responses to questions 4-7, we can determine where assessment and performance objectives are aligned, or at odds, as perceived by students. Figure 4 presents the combined data18Question 4.

Figure 4:

Most vital for a good grade (n=279). 5. Second most vital for a good grades (n=284). 6. Most personally useful (n=287). 7. Second most personally useful (n=287). from all four questions shown as percentages of the total times each skill was selected as either grade-vital or useful. Skills that were as likely to be as grade-vital as they are to be personally useful converge at 50% (i.e.- the ratio approaches 1:1), meaning that these skills are the most ideally balanced between assessment focus (good grades) and performance objectives (usefulness). The further from center the point of convergence, the more out of balance. For instance, “Completing textbook exercises” is assessment-heavy, but is not at all regarded as useful. “Practicing on my instrument” on the other hand is highly useful, but has little effect on assessment.

Most vital for a good grade (n=279). 5. Second most vital for a good grades (n=284). 6. Most personally useful (n=287). 7. Second most personally useful (n=287). from all four questions shown as percentages of the total times each skill was selected as either grade-vital or useful. Skills that were as likely to be as grade-vital as they are to be personally useful converge at 50% (i.e.- the ratio approaches 1:1), meaning that these skills are the most ideally balanced between assessment focus (good grades) and performance objectives (usefulness). The further from center the point of convergence, the more out of balance. For instance, “Completing textbook exercises” is assessment-heavy, but is not at all regarded as useful. “Practicing on my instrument” on the other hand is highly useful, but has little effect on assessment.

No correlation exists between instrument groups/majors and the grade-vital skills. This accurately reflects that all instruments groups participate in the same theory classes and respond to the same assessment criteria. There is a slight indication that monophonic instrument groups tend toward different useful skills (r =.156, p < .05), but all instruments collectively agreed that the most useful skill promoted in the classroom was to actively adapt the concepts to their own personal goals, which likely includes their instrument.

Perceived Learning Outcomes

Often times music students are thought to be confused about the purpose of music theory study. To identify what students perceive to be the overall intended learning outcome of their theory classes, question 3 asked respondents to complete the statement “Music theory intends to teach me–” by choosing one out of eight statements of purpose19How music works; The language of music; musical rules; how to analyze music; how to think about music; musical logic; historical practices; how to compose. commonly found in prefaces to music theory textbooks. The choices were not mutually exclusive, but forced respondents to identify most strongly with one option (n=293, 8 skipped). The top four responses were: “...how music works” (28.6%), “...the language of music” (19.8%), “...how to analyze music” (18.7%), and “...how to think about music” (14.1%).

A weak correlation exists between perceived intended learning outcome and respondents’ primary musical instrument (r =.209, p < .05), with a stronger correlation for specifically monophonic instruments (r =.273, p < .01). There was no correlation with specific music majors. Out the eight possible options, Woodwind and String players were highly likely to believe that music theory class intends to teach “...how music works” (40% and 36%, respectively); Vocalists and Percussionists were most likely to choose “...language of music” (44% and 39%, respectively); and Brass players were most likely to choose “...how to analyze music” (30%). Interestingly, Pianists and Guitarists did not tend toward any particular learning outcome, suggesting that the specialized needs of monophonic instrument players factor into the purpose of theory class. While speculating on the nature of these specializations is tempting,20For instance, Vocalists and Percussionists, though opposite in their method of sound production, are the most intuitively performed instrument groups. Both are likely to see the activities of conventional theory as abstract in relation to their instrument, which might explain why they both chose the most metaphorical learning outcome. Brass players , however, pragmatically have the most to gain from music analysis. Understanding precise harmonic relationships contextualizes their part within their section, and guides the auditory representation of the required pitch prior to its performance. it is beyond the scope of this survey.

Respondents who chose “...how to analyze music” were consistently less positive in their evaluations of theory class than all other intended learning outcomes and were the most likely to write negative comments. This group still generally agreed with the positive statements about music theory knowledge ( = 4.14), but at half of a standard deviation less than other groups ( = 4.54)

Concerns by Primary Major and Instrument

While Pianists and Guitarists might perceive similarly diverse intended learning outcomes, they disagreed somewhat significantly (r =.285, p < .01) about the relevance of the material to their instrument. In question 9 Pianists were the most likely to agree that “Music theory class...is clear about its relevance for my instrument” ( = 3.82), while Guitarists were the least likely ( = 3.21).

Music theory is often related to math class, and one instrument group had significantly stronger feelings about this relationship than all others. 79% of those whose primary instrument was Voice agreed that theory class “Reminds me of math class” ( = 3.60, s = .99), while instrumentalists overall tended to disagree ( = 2.85), resulting in a small positive correlation (r = .208, p < .01). Percussionists, as we might expect, were the least likely to be reminded of math class, more than a full standard deviation below vocalists ( = 2.5, s = .81). This opposition is especially interesting considering that both vocalists and percussionists were the most likely instruments to see “Language of music” as the intended learning outcome of theory class.

Some theory classes include a performance component as part of assessment, such as keyboard skills and sight singing. Strangely, there was some disagreement between majors about the presence of this component, particularly between the two best represented majors: Instrument Performance and Music Education. When asked if their class “includes a performance component as part of my grade” Performance majors were much more likely to disagree (m = 2. = 2.44) than Music Ed. Majors (m = 4, = 3.16), which is a moderately significant difference (r =.348, p < .01). The reasons for this are unclear, as these majors do not differ significantly in any other way. It could be that the term “performance” carries a more specific meaning for Performance majors.

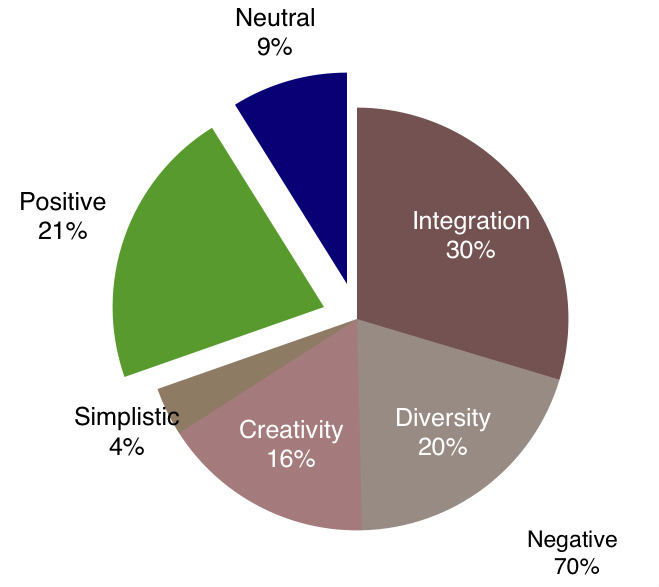

Comments

Question 10 offered respondents an opportunity to openly comment in response to the prompt “What have been the benefits and drawbacks of music theory instruction for you? In what ways could curriculum be improved?” 121 respondents (42%) provided their feedback in comments that ranged from four words to 489 words, averaging roughly 75 words per comment. These were first analyzed for sentiment toward their theory experience (positive, negative, neutral). Responses that had a mix of sentiments were separated,21For example, comment 9 was split into 9a and 9b. 9a: “I like knowing how things work. Having a class that taught me what notes/scales/intervals/chords/progressions turned out to sound and feel like has really helped me to fine tune my musical approach.” and 9b: “It seemed that, both the professors and the curriculum portrayed jazz, and other musical evolutions to be illegitimate in some way.” resulting in 135 unambiguous comments pooled as follows: Negative- 94, Positive- 29, Neutral- 12.

Figure 5:

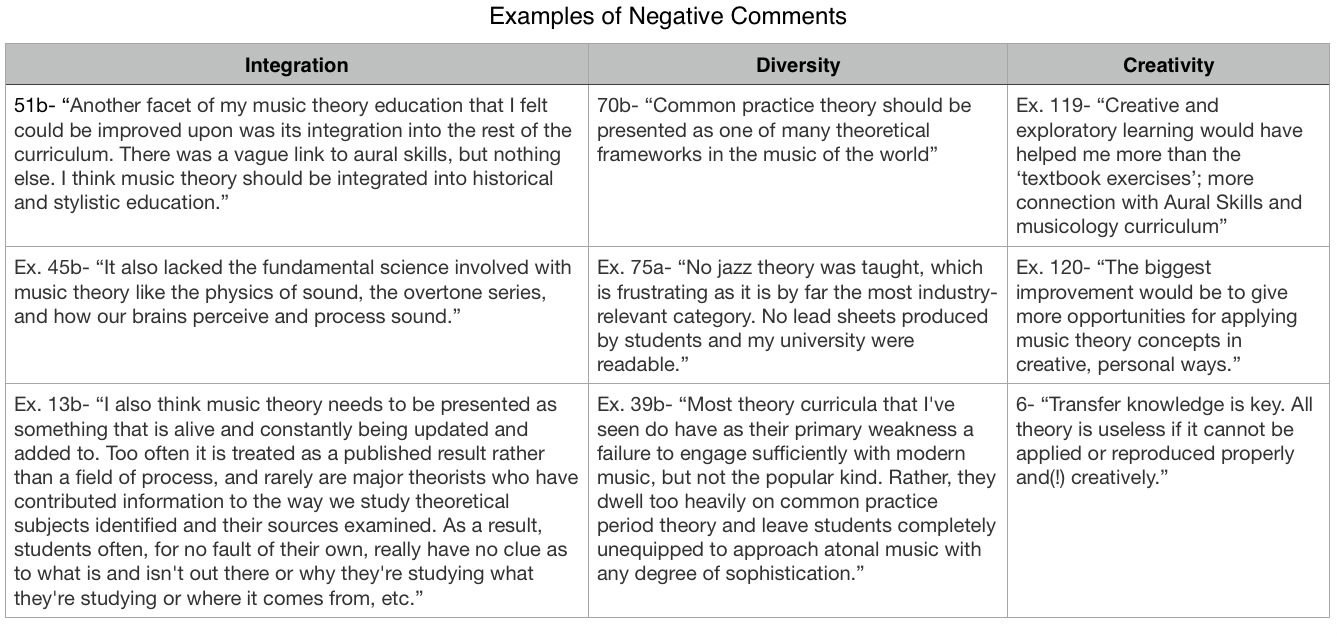

Negative comments expressed clear discontent with one or more aspect of their experience. Most also offered suggestions for improvement. Consistent with the results above, the broad majority of concerns and suggestions fell into one of three categories: integration (40), diversity (27), or creativity (22). Integration concerns include poor communication of the context and purpose of theory study,22Ex. 13b- “I also think music theory needs to be presented as something that is alive and constantly being updated and information being added to. Too often it is treated and ultimately seen as a published result rather than a field of process, and rarely are major theorists who have contributed information to the way we study theoretical subjects identified and their sources examined. As a result, students often, for no fault of their own, really have no clue as to what is and isn't out there or why they're studying what they're studying or where it comes from, etc.” piano-centrism and marginalization of their instrument,23Ex. 30b- “Only complaint, theory classes cater much too heavily to classical musicians especially PIANISTS. Yes piano is a fundamental tool for learning of course, but people are so dismissive of guitar it's just embarrassing how out of touch someone can be. I don't want to learn everything through the lens of piano, translate the lesson to other instruments! a perceived disconnect from student goals,24Ex. 47- “I feel like my theory experience focused a lot on specifics that are not very relevant to my work, and in turn I end up forgetting it.” and lack of integration with other music classes25Ex. 51b- “Another facet of my music theory education that I felt could be improved upon was its integration into the rest of the curriculum. There was a vague link to aural skills, but nothing else. I think music theory should be integrated into historical and stylistic education.” and other related subjects.26Ex. 45b- “It also lacked the fundamental science involved with music theory like the physics of sound, the overtone series, and how our brains perceive and process sound.” 71- “The logic of the curriculum is all wrong. Teaching baroque theory as the central/core form of theory makes no sense in the modern world. I wish more emphasis was laid on the physics of acoustics.” 86- “My struggle in college was that so much time was spent teaching antiquated rules without diving into the sonic and cognitive reasons for those rules.“ Those concerned with diversity were dissatisfied with the exclusive focus on common practice European music27Ex. 45a- “My theory classes focused only on Common Practice "classical" music when in reality it would have benefitted from including different musical genres and music from different cultures.“ 70b- “Common practice theory should be presented as one of many theoretical frameworks in the music of the world.“ to the neglect of other genres28Ex. 52- “My music theory course focused heavily on classical music, so musical concepts which surfaced more noticeably in more modern styles and genres were not sufficiently addressed, nor was the scientific perspective (audiology, psychology, philosophy, etc.)” (including modern music29Ex. 39b- “Most theory curricula that I've seen do have as their primary weakness a failure to engage sufficiently with modern music, but not the popular kind. Rather, they dwell too heavily on common practice period theory and leave students completely unequipped to approach atonal music with any degree of sophistication.” and jazz)30Ex. 75a- “No jazz theory was taught, which is frustrating as it is by far the most industry-relevant category. No lead sheets produced by students and my university were readable.” and the theoretical systems of other cultures.31Ex. 106b- “(I) do wish that it had been more inclusive of other cultures. I think my professors did a good job of covering the full scope of western music, but there is a lot that was left out.” Comments that centered around a lack of creativity in their theory experience expressed that curricula overemphasized analysis32Ex. 73- “Get rid of busy work (roman numeral analysis, twelve tone mapping, etc) and teach in general scopes that will interest performers and help composers - not to write in a particular style - but to incorporate elements into the music they are writing.” and procedures/rules33Ex. 119- “Creative and exploratory learning would have helped me more than the ‘textbook exercises’; more connection with Aural Skills and musicology curriculum.” and undervalued improvisation34Ex. 94b- “Improvisation related music theory has been lacking in my experience.” and creative activities in general.35Ex. 120- “The biggest improvement would be to give more opportunities for applying music theory concepts in creative, personal ways.” 6- “Transfer knowledge is key. All theory is useless if it cannot be applied or reproduced properly and(!) creatively.” 7d- “I feel that over-learning music theory is damaging to the creative process, and I feel that my music theory class treats music as if it is another subject like Maths, where everything is formulaic and has to ‘sound exactly like this.’” In addition to these three categories, five comments were critical of the overly-simplistic approach used by their curriculum.36Ex. 31- “All music theory classes I have taken could have been more constructive if the course was constructed to explore the complexities of music theory rather than hand-wave over them.” Of these 94 negative reviews, seven focused their negativity on the instructor37Ex. 50- “My first semester of college, I had a professor who wasn't great at explaining concepts and I felt very behind in my studies to become a music educator. I ended Theory 1 with a C, barely passing, and reconsidering my career choice. However, my second semester I had a wonderful professor and ended with an A. Now that I've had a more attentive professor, I feel like I now understand more of music, but because of my rough start, I still feel behind compared to other music majors in my school.” rather than the subject generally. See Table 1.1 for examples of negative comments.

Negative comments expressed clear discontent with one or more aspect of their experience. Most also offered suggestions for improvement. Consistent with the results above, the broad majority of concerns and suggestions fell into one of three categories: integration (40), diversity (27), or creativity (22). Integration concerns include poor communication of the context and purpose of theory study,22Ex. 13b- “I also think music theory needs to be presented as something that is alive and constantly being updated and information being added to. Too often it is treated and ultimately seen as a published result rather than a field of process, and rarely are major theorists who have contributed information to the way we study theoretical subjects identified and their sources examined. As a result, students often, for no fault of their own, really have no clue as to what is and isn't out there or why they're studying what they're studying or where it comes from, etc.” piano-centrism and marginalization of their instrument,23Ex. 30b- “Only complaint, theory classes cater much too heavily to classical musicians especially PIANISTS. Yes piano is a fundamental tool for learning of course, but people are so dismissive of guitar it's just embarrassing how out of touch someone can be. I don't want to learn everything through the lens of piano, translate the lesson to other instruments! a perceived disconnect from student goals,24Ex. 47- “I feel like my theory experience focused a lot on specifics that are not very relevant to my work, and in turn I end up forgetting it.” and lack of integration with other music classes25Ex. 51b- “Another facet of my music theory education that I felt could be improved upon was its integration into the rest of the curriculum. There was a vague link to aural skills, but nothing else. I think music theory should be integrated into historical and stylistic education.” and other related subjects.26Ex. 45b- “It also lacked the fundamental science involved with music theory like the physics of sound, the overtone series, and how our brains perceive and process sound.” 71- “The logic of the curriculum is all wrong. Teaching baroque theory as the central/core form of theory makes no sense in the modern world. I wish more emphasis was laid on the physics of acoustics.” 86- “My struggle in college was that so much time was spent teaching antiquated rules without diving into the sonic and cognitive reasons for those rules.“ Those concerned with diversity were dissatisfied with the exclusive focus on common practice European music27Ex. 45a- “My theory classes focused only on Common Practice "classical" music when in reality it would have benefitted from including different musical genres and music from different cultures.“ 70b- “Common practice theory should be presented as one of many theoretical frameworks in the music of the world.“ to the neglect of other genres28Ex. 52- “My music theory course focused heavily on classical music, so musical concepts which surfaced more noticeably in more modern styles and genres were not sufficiently addressed, nor was the scientific perspective (audiology, psychology, philosophy, etc.)” (including modern music29Ex. 39b- “Most theory curricula that I've seen do have as their primary weakness a failure to engage sufficiently with modern music, but not the popular kind. Rather, they dwell too heavily on common practice period theory and leave students completely unequipped to approach atonal music with any degree of sophistication.” and jazz)30Ex. 75a- “No jazz theory was taught, which is frustrating as it is by far the most industry-relevant category. No lead sheets produced by students and my university were readable.” and the theoretical systems of other cultures.31Ex. 106b- “(I) do wish that it had been more inclusive of other cultures. I think my professors did a good job of covering the full scope of western music, but there is a lot that was left out.” Comments that centered around a lack of creativity in their theory experience expressed that curricula overemphasized analysis32Ex. 73- “Get rid of busy work (roman numeral analysis, twelve tone mapping, etc) and teach in general scopes that will interest performers and help composers - not to write in a particular style - but to incorporate elements into the music they are writing.” and procedures/rules33Ex. 119- “Creative and exploratory learning would have helped me more than the ‘textbook exercises’; more connection with Aural Skills and musicology curriculum.” and undervalued improvisation34Ex. 94b- “Improvisation related music theory has been lacking in my experience.” and creative activities in general.35Ex. 120- “The biggest improvement would be to give more opportunities for applying music theory concepts in creative, personal ways.” 6- “Transfer knowledge is key. All theory is useless if it cannot be applied or reproduced properly and(!) creatively.” 7d- “I feel that over-learning music theory is damaging to the creative process, and I feel that my music theory class treats music as if it is another subject like Maths, where everything is formulaic and has to ‘sound exactly like this.’” In addition to these three categories, five comments were critical of the overly-simplistic approach used by their curriculum.36Ex. 31- “All music theory classes I have taken could have been more constructive if the course was constructed to explore the complexities of music theory rather than hand-wave over them.” Of these 94 negative reviews, seven focused their negativity on the instructor37Ex. 50- “My first semester of college, I had a professor who wasn't great at explaining concepts and I felt very behind in my studies to become a music educator. I ended Theory 1 with a C, barely passing, and reconsidering my career choice. However, my second semester I had a wonderful professor and ended with an A. Now that I've had a more attentive professor, I feel like I now understand more of music, but because of my rough start, I still feel behind compared to other music majors in my school.” rather than the subject generally. See Table 1.1 for examples of negative comments.

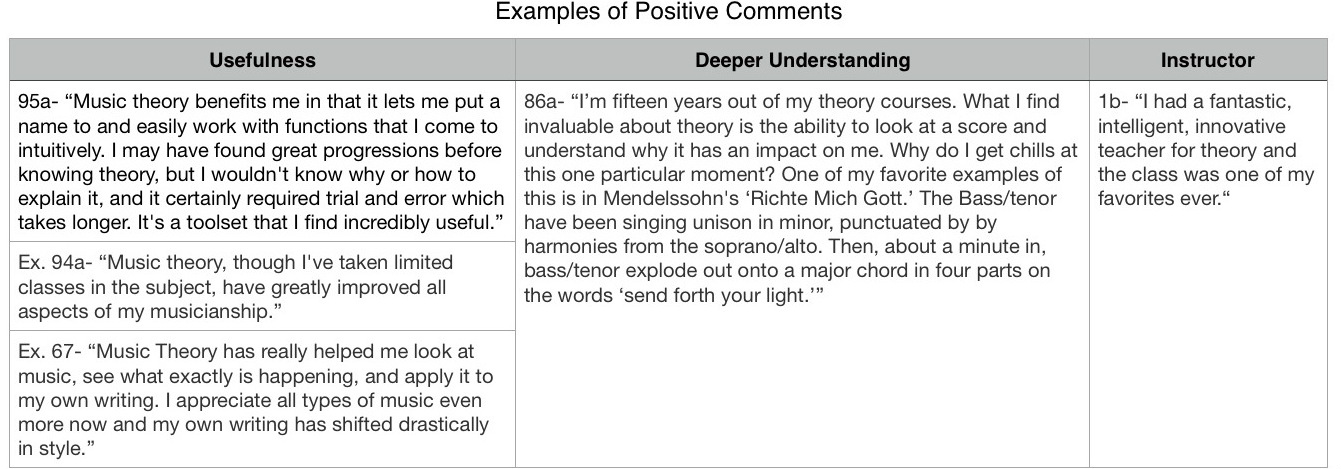

Positive comments, even if accompanied by a suggestion for improvement, centered around three themes: usefulness (16), deeper understanding (8), and instructor-specific experiences (5). While the majority of negative comments focused on the inapplicability of their theory experience, the largest pool of positive comments praised theory precisely for its usefulness, be it the contribution to their own creative work,38Ex. 67- “Music Theory has really helped me look at music, see what exactly is happening, and apply it to my own writing. I appreciate all types of music even more now and my own writing has shifted drastically in style.” their instrument,39 61a- “Music theory is great, especially as a pianist, it's useful. musical communication,4095a- “Music theory benefits me in that it lets me put a name to and easily work with functions that I come to intuitively. I may have found great progressions before knowing theory, but I wouldn't know why or how to explain it, and it certainly required trial and error which takes longer. It's a toolset that I find incredibly useful.” listening skills,4143a- “Benefit: I can identify intervals more quickly, which helps me improvise more accurately (violin player).” or general musicianship.42Ex. 94a- “Music theory, though I've taken limited classes in the subject, have greatly improved all aspects of my musicianship.” Other students appreciated the deeper understanding they gained,43 Ex. 69- “Music Theory was the best class I've ever taken, and I hope to take it again. It has greatly widened my understanding, and creative ideas of, and within music. There is so much good the class has brought me, and none bad.” even if not directly for a practical application.4486a- “I’m fifteen years out of my theory courses. What I find invaluable about theory is the ability to look at a score and understand why it has an impact on me. Why do I get chills at this one particular moment? One of my favorite examples of this is in Mendelssohn's ‘Richte Mich Gott.’ The Bass/tenor have been singing unison in minor, punctuated by by harmonies from the soprano/alto. Then, about a minute in, bass/tenor explode out onto a major chord in four parts on the words ‘send forth your light.’” Five comments recognized the centrality of their instructor in their positive experience.451b- “I had a fantastic, intelligent, innovative teacher for theory and the class was one of my favorites ever.” See Table 1.2 for examples of positive comments.

Positive comments, even if accompanied by a suggestion for improvement, centered around three themes: usefulness (16), deeper understanding (8), and instructor-specific experiences (5). While the majority of negative comments focused on the inapplicability of their theory experience, the largest pool of positive comments praised theory precisely for its usefulness, be it the contribution to their own creative work,38Ex. 67- “Music Theory has really helped me look at music, see what exactly is happening, and apply it to my own writing. I appreciate all types of music even more now and my own writing has shifted drastically in style.” their instrument,39 61a- “Music theory is great, especially as a pianist, it's useful. musical communication,4095a- “Music theory benefits me in that it lets me put a name to and easily work with functions that I come to intuitively. I may have found great progressions before knowing theory, but I wouldn't know why or how to explain it, and it certainly required trial and error which takes longer. It's a toolset that I find incredibly useful.” listening skills,4143a- “Benefit: I can identify intervals more quickly, which helps me improvise more accurately (violin player).” or general musicianship.42Ex. 94a- “Music theory, though I've taken limited classes in the subject, have greatly improved all aspects of my musicianship.” Other students appreciated the deeper understanding they gained,43 Ex. 69- “Music Theory was the best class I've ever taken, and I hope to take it again. It has greatly widened my understanding, and creative ideas of, and within music. There is so much good the class has brought me, and none bad.” even if not directly for a practical application.4486a- “I’m fifteen years out of my theory courses. What I find invaluable about theory is the ability to look at a score and understand why it has an impact on me. Why do I get chills at this one particular moment? One of my favorite examples of this is in Mendelssohn's ‘Richte Mich Gott.’ The Bass/tenor have been singing unison in minor, punctuated by by harmonies from the soprano/alto. Then, about a minute in, bass/tenor explode out onto a major chord in four parts on the words ‘send forth your light.’” Five comments recognized the centrality of their instructor in their positive experience.451b- “I had a fantastic, intelligent, innovative teacher for theory and the class was one of my favorites ever.” See Table 1.2 for examples of positive comments.

Neutral comments were neither positive or negative,46 30a- “Musicology + intense theory study worked very well for me.“ or they directed their sentiment toward non-curricular factors, such as the shortcomings of students themselves.4778- “I think the biggest problem is the lack of enthusiasm music students have to learn and understand these issues.”

Discussion

The results show strong evidence that undergraduate music theory has been a largely positive experience for students, who overall view the subject of music theory as highly beneficial, useful, and as providing a competitive edge for a musical career. Remarkably, however, fewer than 99% of respondents had something negative to report, with students largely agreeing on the most prominent shortcomings of theory class and curriculum. An analysis of multiple choice responses, Likert scale questions, and open comments all pointed to three primary areas of discontent. They are, in order of importance: integration, diversity, and creativity.

Overall, the classroom shines when it emphasizes creative engagement and applicability to students’ personal musical goals. Students who saw personal engagement as the core purpose of theory were the most positive in their evaluation. Theory class becomes frustrating when its scope is limited to keyboard-driven and common practice music with minimal explanation of its historical, cultural, and scientific contexts. Students who saw analysis as the primary purpose were significantly more negative in their evaluation.

Results also reveal a perceived mismatch between assessment and student objectives, where the most assessed activities are often the least valuable to students, and vice versa. Importantly, however, assessment and objectives are balanced ideally in three areas: engaging creatively with the material, analytic listening, and score analysis. Contrary to the claim that contemporary students (and progressive scholars) tend to “romanticize musical illiteracy” (Pace, 2017), this shows that students really do find value in analysis and listening skills, even as they pertain to common practice music. However, the value is profoundly enhanced when students are engaged with actively, creatively and personally.

Musical experience is inextricable from the process of learning theory. Results affirm that the variability of student experience not only accounts for variations in its application (i.e. why a brass player would find analysis more useful than a percussionist), but also for variations in the perception of what music theory intends to teach them at all. This variation was especially evident for players of monophonic instruments (including voice). This evidence supports that there is a real danger in instructors placing the cart before the horse, to borrow from educationalist David Borgo, who states– “...we only err when we place the cart of music theory before the horse of musical experience—or, more accurately, when we conceptualize them as entirely distinct from one another” (Borgo, 2007).

But at what level does such integration begin? Is the onus on the curricula, on the instructor, on the administration to tailor course content to these diverse musical experiences? For instance, special consideration could be given to vocalists, who are more likely to associate music theory with math class; performance majors could be assessed based more on performance, and music education majors based on a sample lesson. While generalized music theory curricula were never intended to offer personalized accommodation, online learning and the flipped-classroom model has made an individualized experience in a classroom more accessible than ever before. The results of this survey offer no evidence that students are asking for such specialized attention. They neither demand or expect a theory class fully customized to their own goals and interests. Rather, they ask for a class that leaves room for their experiences to play a more central role in the in-formation process.

Even in critiquing its narrow focus, students are not calling for the wholesale abandonment of common practice theory. The global importance of common practice music is undeniable, and it deserves to be explored in depth, but can be done so without the implying notions of objective superiority to other rich theoretical systems.48For example: Tuning systems of Balinese gamelan, rhythmic studies of North Indian tabla, and Afrological streams of influence: African and African American models of musicking, with their diasporic expressions such as Afro‐Cuban, Afro‐ Columbian, Afro‐Brazilian, Afro‐Bolivian, and Afro-Mexican styles. The keyboard also allows the abstractions of music theory to be made accessible visually, audibly, and haptically, with minimal technical demands placed on the student. Its replacement as the world’s de facto musical instrument is highly unlikely for the foreseeable future.

There is also a reason for the mismatch between assessment and student objectives. The most valuable aspects of theory class (according to survey data) center around creative engagement, and no one has yet figured out how to fairly or reliably measure musical creativity. Increasingly the attempt to standardize creativity reveals that this is less a curricular issue than it is logically untenable. Creativity is metric averse, and for the time being there is no way around this. Curricula must, in the words of Pamela Burnard, reject the “simple linear conception of a single creativity for one super-genre, ‘music’” and instead allow for (not cater to) “a multiplicity of musical creativities deriving from the complexity of the social world in which the musician is located.”49Burnard, Musical Creativities in Practice, 3.

Recommendations such as Burnard’s remind us of the paradoxical existence music theory has been called to lead in its timeless straddling of theoria and praktike. It can certainly be argued that in their reach to accommodate such multiplicity, students and scholars such as Burnard are exceeding their grasp, practically speaking. The current challenge for theory instructors is to teach a theory dually concerned with nurturing musical competence and developing new musical creativities, with common practice music and crossing territories. If students’ input presented here is at all representative of the future of the discipline, what might this indicate about the character of its evolution?

Recommendations

The results overall are remarkably in phase with a paradigm that has experienced a resurgence in cognitive science, education studies, and even recent music scholarship. James Gibson’s ecological view of perception argues that sensory perception develops in response to action-directed opportunities (affordances) that exist in the relationship between an organism and its environment (Gibson, 1983). Organisms, in this view, perceptually map their environment in response to, and explore their world in search of, these opportunities to act. The combination of what has been explored and what there is yet to be evaluated is actually what comprises one’s environment. Through exploration one discovers affordances– a knob affords twisting, a cord affords pulling, a piano affords polyphony. As a relation, an affordance exhibits the possibility of some action, and is not a property of either an organism or its environment alone. Carl Rogers, a prominent figure in phenomenological psychology and existential psychotherapy, often spoke of “attitudinal qualities” in learning environments that resemble Gibson’s affordances– “the facilitation of significant learning rests upon certain attitudinal qualities which exist in the relationship between the facilitator and the learner.”50Rogers, “The Interpersonal Relationship in the Facilitation of Learning.” For Rogers, the only mode in which this deeply significant learning can take place is exploration– “To free curiosity; to open everything to questioning and exploration; to recognize that everything is in process of change–here is a [learning] experience I can never forget.”

Consider a music theory class as an ecological system, with a domain (the subject itself), a hierarchy (instructor/student), incentives (grades), time constraints (exams, semester), conceptual constraints (curricula), goals (learning objectives), the known (prior musical experience), and the unknown (the unknown). How might integration, creativity and diversity be better represented in this environment? The first step is to understand that no class is an isolated ecosystem, which is contrary to what is suggested by the standard practice of treating courses as discrete blocks of tangibly related information. Rather, each course represents only a small domain within which learners might identify affordances that help them both to achieve their existing goals and to define new goals within the context of their own ecological situation (musical experience, culture, instrument, style, career interests, etc.). Interpreting the survey through this lens, the overall positive feedback reflects that most students found theory class to be rich in affordance potential, that is, in “theory” (appropriately). The negative feedback reflects that the action potential offered “in theory” was not always converted into to actions that actually aligned with student goals. The lack of “integration” reported by students can be seen as precisely this disconnect between the affordances assumed by the curriculum and instructors, and the affordances sought by learners.

A reasonable recommendation might be to adjust existing curricular standards at the university level up to the level of the accrediting agency. However, recent evidence suggests that such top-down guidelines already have quite a minimal impact on the music theory classroom. In her 2015 research Vicky Johnson discovered that none of the accredited institutions in her state were operating in compliance with the standards and mandates of either the National Association of Schools of Music or the state certification boards (Johnson, 2015). Completely in step with student reports in this study, these institutions deviated from standards primarily in their lack of emphasis on (1) creative activities and (2) music outside the common practice period. Furthermore, professors and instructors who were surveyed considered skills and competencies related to reading music to be the most important and those related to creating music to be the least important for both freshman music majors and in-service school music teachers. Since it seems then that top-down standards have been ineffective, perhaps the voices of the students calling for essentially the same changes currently mandated might provide the needed pressure to faculty and instructors to continue progressing toward substantive change.

Changing attitudes and coordinated efforts on the part of faculty are required to bring this about. Although Harvard is unique among notable institutions to wave the music theory requirement, alternative approaches have been in development over the past decade. For example, the Frost School of Music at the University of Miami has successfully adopted a fully integrated approach in which practice-oriented through-lines are threaded between theory, history, ear-training, solo and ensemble performance, composition and improvisation, and entrepreneurship, melding together what are usually disconnected and only vaguely continuous curricular blocks. By monitoring forward thinking (and forward acting) schools such as Frost, and–more importantly– listening to the voices of their students, theory pedagogy can begin to make more informed curricular choices with confidence.