Abstract

To increase understanding of the promotion and tenure process for music professors, the CMS Academic Citizenship Committee studied four aspects of the topic: the promotion and tenure process; expectations for excellence in teaching, scholarship/creative activities, and service; the support systems available to assist new music professors toward promotion and tenure; and conditions that may influence promotion and tenure decision-makers. A survey, designed to reveal the current range of promotion and tenure practices, was distributed to the entire CMS membership. Results are based on the responses of 1539 CMS members from diverse music teaching areas.

We found the promotion and tenure process for music professors is similar to practices in other disciplines. For music professors (as in other disciplines) teaching, scholarship/creative activity, and service are given different importance at diverse Carnegie institution types. Music professors may be expected to participate in national and international conferences and publish in peer-reviewed journals like their colleagues in other fields. Unlike other professors, however, a music professor's creative activity may include, for example, appearances in peer-reviewed public performances, and professional recordings. CMS members report that many institutions have written policies in place that clarify expectations and assessment criteria for creative activity. Service activity for music professors appears to be of less importance in promotion and tenure decisions than teaching and scholarship/creative activity. Finally, almost all professors have access to group mentoring on their campus. Individual mentoring, either by senior department colleagues or department chairs is much less available.

While promotion and tenure are well-established traditions in colleges and universities the processes and criteria for assessment and decision-making are likely to differ widely among CMS members’ institutions. The tenure process can be daunting for those undergoing reviews and for those who make judgments about their early-career colleagues (Brown, 2012). The promotion and tenure process may be particularly challenging for professors in the arts because activity and achievement – and how it is evaluated- may be quite different than for disciplines outside of the arts. For example, music professors may teach in less usual settings, such as one-to-one music performance instruction in a studio or directing a large ensemble on a concert stage rather than in traditional classrooms. In addition, music professors’ creative activities and scholarly works are also likely to be different from professors in non-arts fields and may include new compositions and performances (solo or ensemble) along with traditional scholarly achievements.

Promotion and tenure decisions have a lasting impact on the lives and careers of music professors. Hence, a clear understanding of both the process and criteria employed by evaluators is essential. Understanding factors that contribute to promotion and tenure decisions at different types colleges and universities may yield insights that can serve to clarify the process for both the professors going through the promotion and tenure process and the evaluators and mentors who participate in the process. Previous researchers have reported that some college promotion and tenure processes as have contradictory criteria and unwritten rules (Rice, Sorcinelli, & Austin, 2000, p. 9), that may be characterized as mysterious, politicized and a “crapshoot” (Chait, 1997, p. B4). The goal of this research, undertaken by the College Music Society’s Academic Citizenship Committee1Members of the College Music Society Academic Citizenship Committee in 2014 included Hal Abeles, Alicia Doyle, Robert J. Jones, Mary Ellen Junda, David Montano, Anne Patterson, and Anna Song. , is to help clarify the promotion and tenure process in music units and “to examine if the intense focus on measuring and rewarding individual academic and creative productivity might actually be encouraging more independent agency rather than collegial and cooperative cross-disciplinary work that is more responsive and relevant to the needs and expectations of students and the civic community” (College Music Society [CMS], 2014).

One assumption of this study is that the perception of fairness and equity in promotion and tenure is related to being well informed about the process. In a recent study (Bradley et al., 2017) of the tenure process for music faculty members in Canadian universities, it was reported that “...transparency in the tenure process contributed to a somewhat smoother path to tenure” (p. 12). Another assumption is that the availability of support (both financial and in terms of mentorship) towards achieving the expectations for tenure or promotion at a particular institution assists those seeking tenure. Lawrence, Celis, and Ott (2014) report that three factors particularly influenced the perceived fairness of the process: perceived equitable treatment of junior faculty, effectiveness of feedback given to junior faculty prior to the tenure decisions, and satisfaction with professional and personal interactions with pre-tenure and tenured faculty in their departments (collegiality) (p.174). The effectiveness of mentoring efforts was also identified as a contributing factor in junior faculty members’ perception of fairness in the tenure process (p. 172).

Mentoring of junior professors has increasingly become an expected component of early career faculty development. Research confirms that mentors can have a positive effect on junior faculty member’s academic success (Hobson, 2012; Morrison et al., 2014). Hobson indicated that mentoring may be the most effective strategy for supporting early academic careers. A study by Iversen, Eady, and Wessely (2014) showed that academic mentors are able to enhance mentee’s confidence and increase mentee’s commitment to pursuing a career in academics, although they also found that not all mentoring relationships were successful. Some studies on mentoring show that in less successful mentoring relationships there was little follow-up after mentoring meetings, the mentoring meetings often lacked structure, and that because of demanding work loads it was often difficult to find time to schedule meetings (Iversen et al., 2014; Gillespie et al. 2012). One of the important outcomes of effective mentoring relationships, however, is that junior professors are often able to develop an understanding of what is expected in the promotion and tenure process at their institution (Schrodt, Cawyer, C., & Sanders, 2003).

New music professors need to know two critical things early in their careers. First, they need an understanding of performance criteria for promotion and tenure at their particular institution and second, they must know what evidence they are expected to present for their tenure review (Lawrence, et al., 2014). In addition, new faculty members need to understand how the three traditional criteria for promotion and tenure, teaching, scholarship, and service are prioritized at their institution.

The purpose of this study was to describe the promotion and tenure process in CMS members’ schools and departments of music. The study sought answers to the following research questions: a) Is the process for promotion and tenure for music faculty similar to the process for other disciplines across campus? (b) Are the expectations for teaching, scholarship/creative activities and service for music faculty, similar to the expectations in other disciplines? (c) What kind of support systems are available to assist new music faculty members in meeting the expectations for tenure and promotion? and (d) How faculty members characterize department, college, and university conditions that may influence promotion and tenure decisions such as the administration’s management style and faculty collegiality?

Method

The CMS Academic Citizenship Committee is comprised of members who believe that “responsible academic citizenship demands engaged, collegial, and collaborative participation in the full life of the college/conservatory/university...” ("About Academic Citizenship," The College Music Society, www.music.org). During the Committee’s 2013 Conference open forum entitled “Building Inclusivity in the Exclusive Academy,” a common concern emerged: that current promotion and tenure processes might actually be hindering the development of collegial and collaborative academic citizenship.

As a group, we proposed a panel presentation to address relevant tenure and promotion issues to be held at the 2015 national conference in St. Louis, MO. In order to begin the dialog, we designed a survey that was distributed to the entire CMS membership. The survey assessed the current status of promotion and tenure practices and solicited ideas for how current practices might be improved to encourage the development of ever more collegial, collaborative, and civic-minded academic citizens. Each question was formulated to ensure that the data we collected measured the intended objective. Each question was checked for bias and the entire survey was pre-tested before it went live. The survey results were then analyzed in order to develop suggestions for best practices in the area of promotion and tenure.

Findings

The Respondents

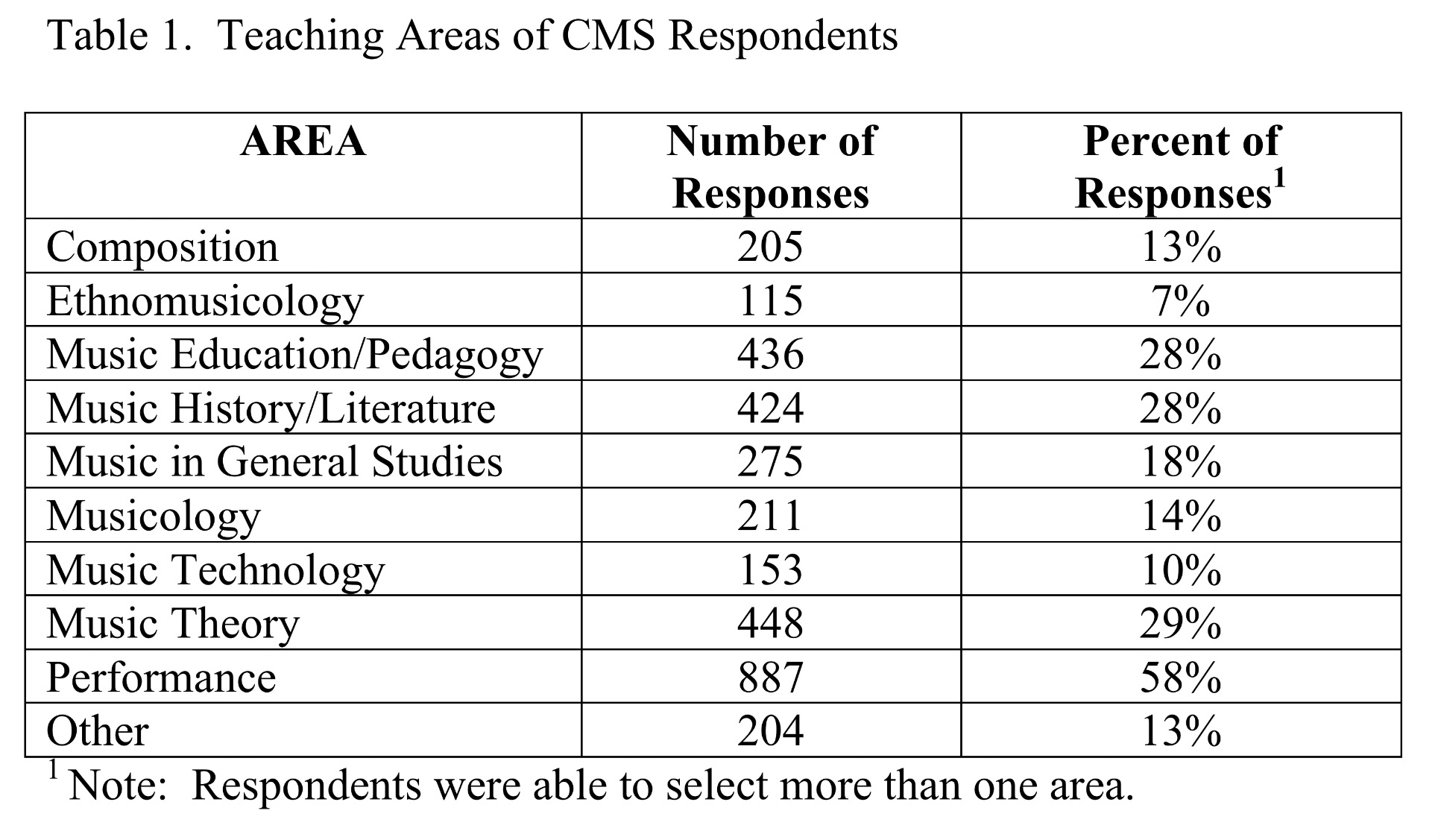

Responses were received from 1539 CMS members who represented diverse teaching areas with music. Table 1 displays the different teaching areas represented by the respondents.

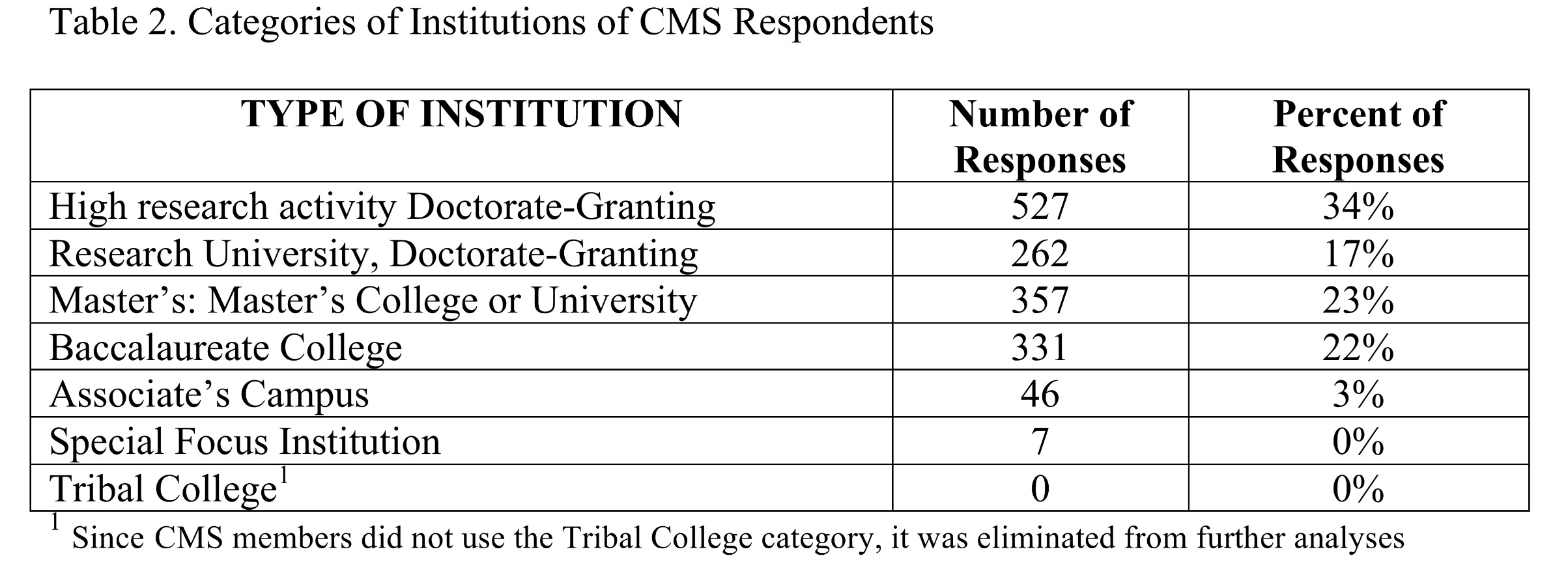

The respondents also worked at different types institutions. We used an adaptation of the Carnegie classification system to organize institutional types. The types of institutions identified by the respondents appear in Table 2.

The respondents also worked at different types institutions. We used an adaptation of the Carnegie classification system to organize institutional types. The types of institutions identified by the respondents appear in Table 2.

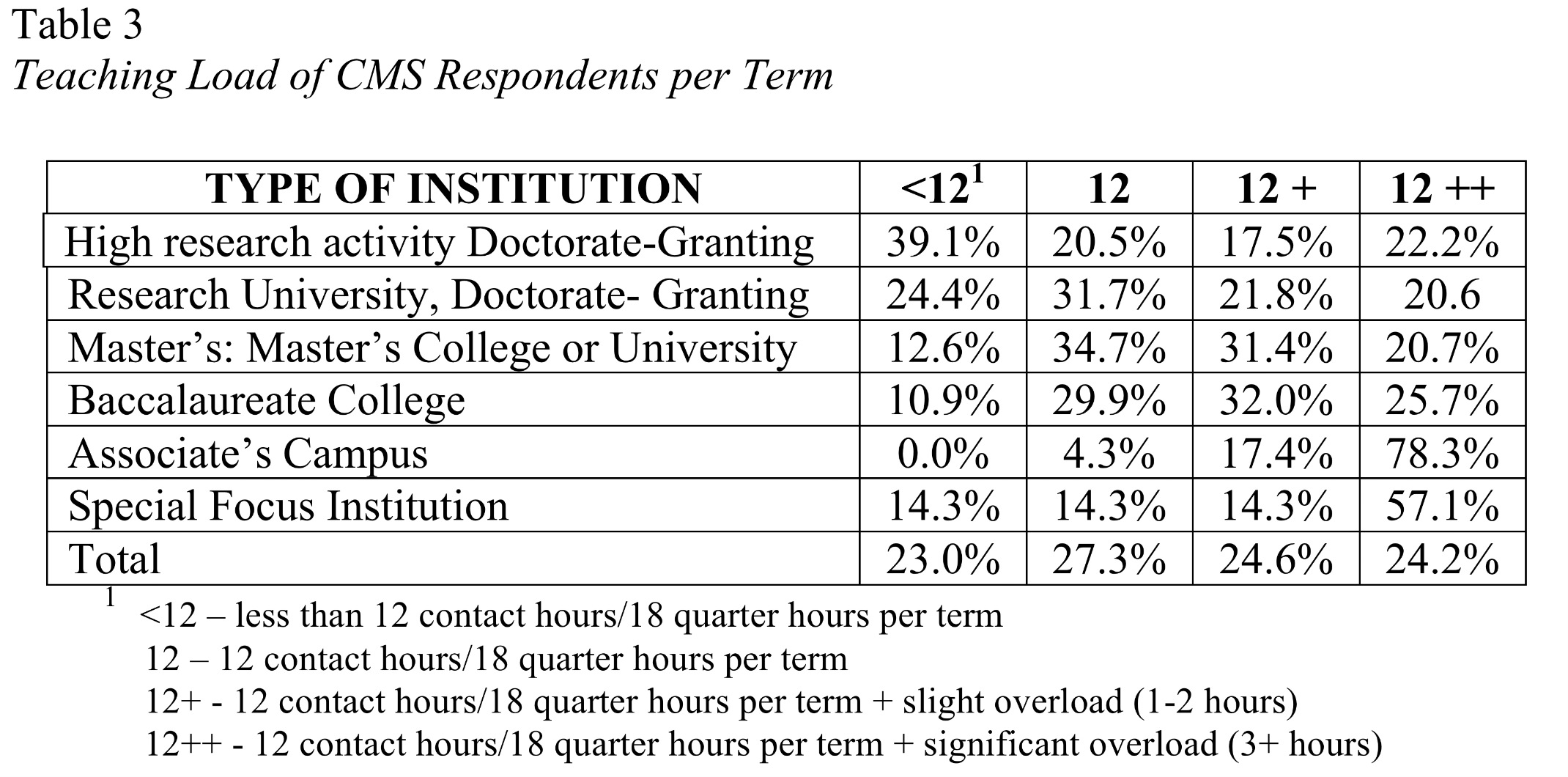

A review of Table 2 shows that majority (51%) of the respondents taught and doctoral granting institutions with almost three-quarters of them (74%) teaching at graduate institutions. It is often assumed that institutions that require high research and creative activity productivity have somewhat reduced teaching loads. Research by Hattie and Marsh (1996) confirm that assumption. Yet, Table 3 reveals more than three-quarters of the respondents (76%) taught 12 contact hours per semester (18 quarter hours) or more. Table 3 details the responses to a survey question regarding teaching load.

A review of Table 2 shows that majority (51%) of the respondents taught and doctoral granting institutions with almost three-quarters of them (74%) teaching at graduate institutions. It is often assumed that institutions that require high research and creative activity productivity have somewhat reduced teaching loads. Research by Hattie and Marsh (1996) confirm that assumption. Yet, Table 3 reveals more than three-quarters of the respondents (76%) taught 12 contact hours per semester (18 quarter hours) or more. Table 3 details the responses to a survey question regarding teaching load.

The results reported in Table 3 do show a relationship between the type of institution and the number credit hours taught per term with a majority (59.6%) of music faculty members at high research activity universities teaching 12 credit hours per semester or less, while a majority of music faculty (57.7%) at baccalaureate colleges teaching either slightly more or significantly more than 12 credit hours per semester. The data in Table 3 were subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 241.91, df =15, p < .001) indicate that the pattern of teaching loads across institutional type does differ significantly2 In this paper statistical significance was defined as p < .05. .

The results reported in Table 3 do show a relationship between the type of institution and the number credit hours taught per term with a majority (59.6%) of music faculty members at high research activity universities teaching 12 credit hours per semester or less, while a majority of music faculty (57.7%) at baccalaureate colleges teaching either slightly more or significantly more than 12 credit hours per semester. The data in Table 3 were subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 241.91, df =15, p < .001) indicate that the pattern of teaching loads across institutional type does differ significantly2 In this paper statistical significance was defined as p < .05. .

Approximately one-quarter (24%) of CMS members reporting indicated that the institution where they worked has a faculty union. Approximately one-quarter (23%) of both unionized and non-unionized faculty taught less than 12 hours per semester, about one-quarter (27%) taught 12 hours per semester, about one-quarter (24%) had a slight overload and about one-quarter (24%) taught significantly more than 12 hours per semester. An analysis of the relationship between teaching load and having a faculty union did not show a statistically significant relationship (Chi-square test of homogeneity: Pearson Chi-square = 9.07, df =3, p = NS), that is, music faculty members who are teaching on a campus that has a faculty union are not likely to teach less (or more) than music faculty members who are on a campus that does not have a faculty union.

Factors related to tenure and promotion

Pre-tenure support. To obtain a general parameter for the tenure process, we asked CMS members, “What is the expected probationary period before tenure at your institution?” The average number of years in the probationary period was 5.83. The most frequently reported period was 6 years, (60.5%) followed by 7 years (17.3%) and 5 years (14.4%). Twenty-three of the respondents (2.4%) reported that their institution did not have tenure.

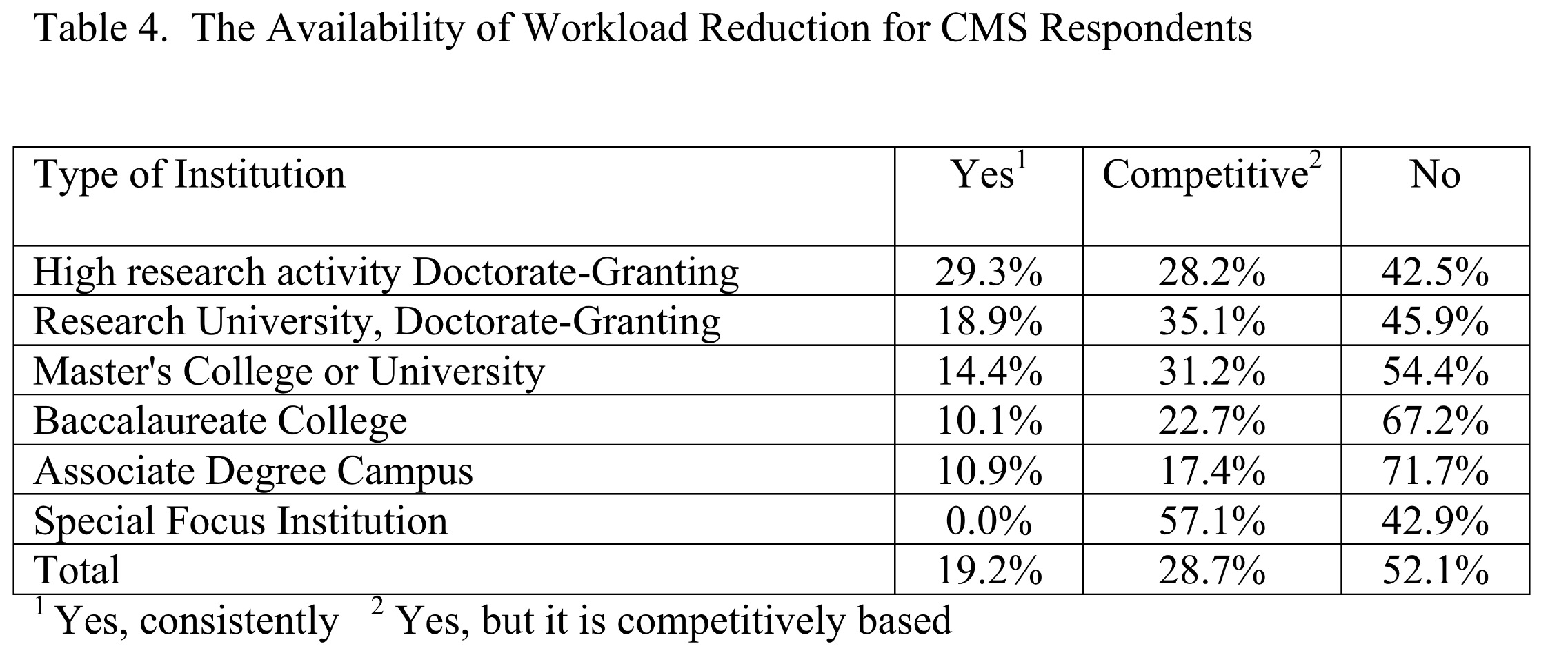

One strategy that institutions may use to support the ability of junior faculty members to achieve tenure is to reduce their workload so that they may focus on scholarship and/or creative activity. Respondents were asked, “Does your institution offer workload reduction for scholarly research and/or creative activity?” The results showed that approximately 19% of the institutions consistently had workload reductions available, while about 28% offered competitive workload reduction opportunities. The remaining institutions (52%) did not offer course load reductions for junior faculty. When the results were further analyzed (see Table 4) they demonstrated that the availability of workload reduction is related to institutional type.

Table 4 reveals that workload reduction is most available at doctoral granting institutions and least available at baccalaureate, associate degree, and special focus institutions. The data in Table 4 were analyzed using a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 90.69, df =10, p < .001) indicate that the pattern of the availability of workload reduction across institutional type differs significantly.

Table 4 reveals that workload reduction is most available at doctoral granting institutions and least available at baccalaureate, associate degree, and special focus institutions. The data in Table 4 were analyzed using a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 90.69, df =10, p < .001) indicate that the pattern of the availability of workload reduction across institutional type differs significantly.

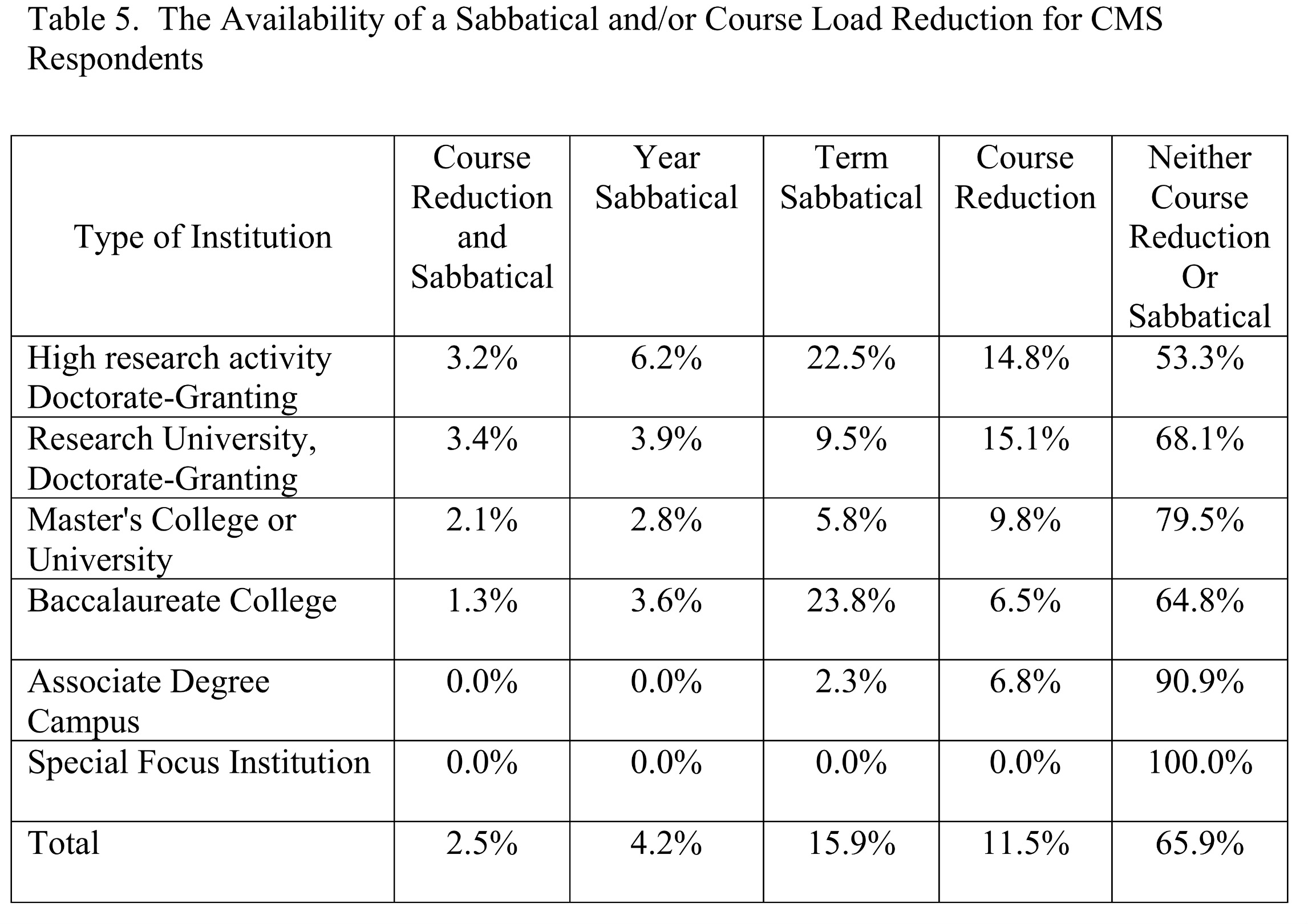

Respondents were asked a similar question about the availability of a term or full-year sabbatical before receiving tenure and/or a course load reduction. Table 5 displays the results of the responses by type of institution.

Similar to the pattern in Table 4, Table 5 reveals that while the availability of a sabbatical leave and/or course load reduction is not common, it is most available at doctoral granting institutions and least available at master’s degree, associate degree, and special focus institutions. The data in Table 5 were also subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 113.14, df =20, p < .001) indicate that the pattern of the availability of sabbatical leaves and/or course load reduction across institutional type is significantly different.

Similar to the pattern in Table 4, Table 5 reveals that while the availability of a sabbatical leave and/or course load reduction is not common, it is most available at doctoral granting institutions and least available at master’s degree, associate degree, and special focus institutions. The data in Table 5 were also subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 113.14, df =20, p < .001) indicate that the pattern of the availability of sabbatical leaves and/or course load reduction across institutional type is significantly different.

Importance of different criteria

A key factor in the promotion and tenure process is how much weight in the evaluation process is given to each of the three traditional areas of expected faculty work: teaching, scholarship/creative activity, and service. There is a general expectation that different types of higher education institutions, with different missions, place differential importance on these three areas. For example, we might expect that research-focused doctoral granting institutions would place more emphasis on faculty members’ success in the research and creative activity category, while institutions that focus on baccalaureate education might focus more on a faculty members teaching ability. Research by Nadler (1999) confirms that institutions with different Carnegie classifications employ different criteria for evaluating faculty for promotion and tenure.

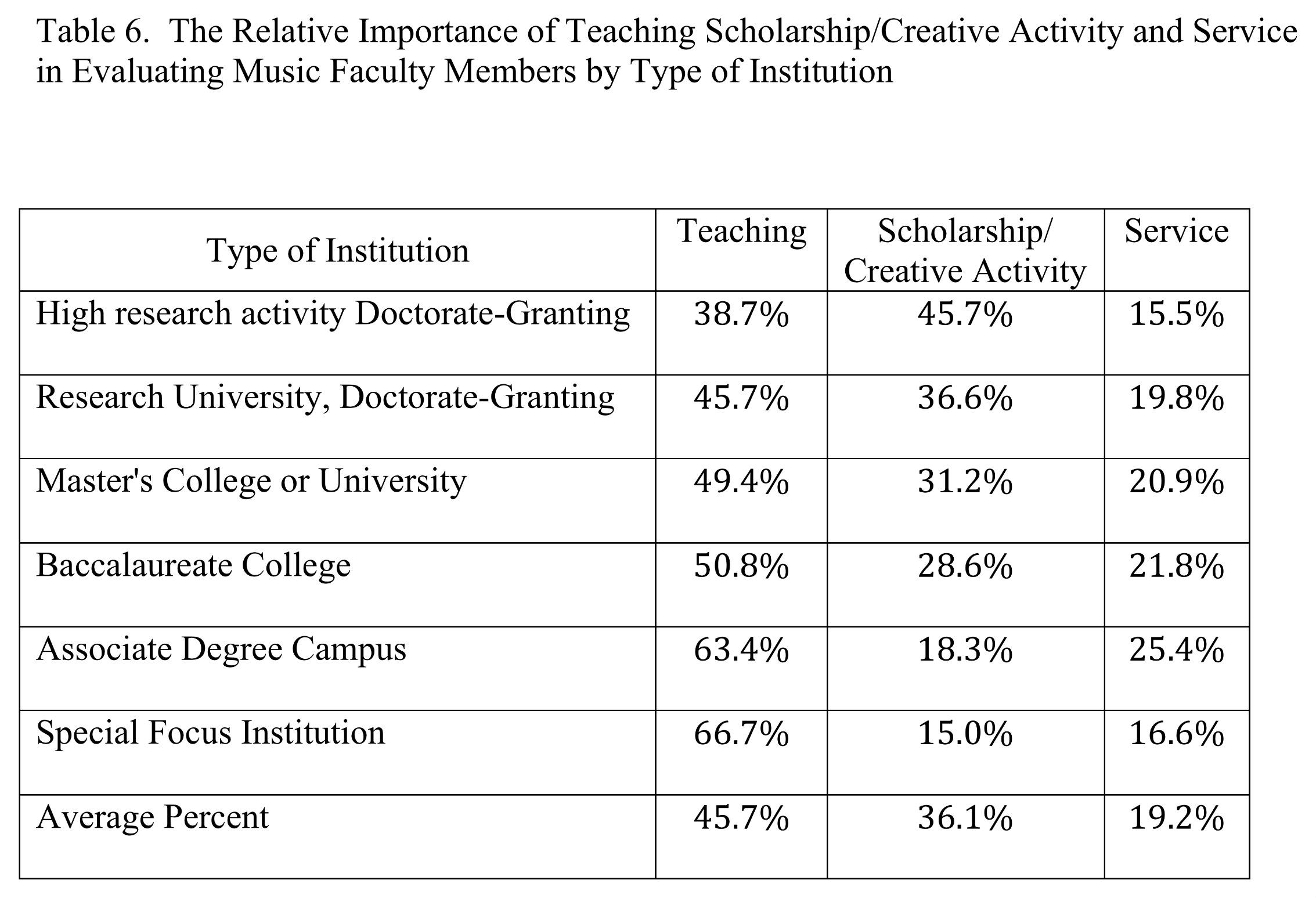

To examine this issue within the discipline of music, CMS members were asked to report how teaching, scholarship/creative activities, service, and “other” work were weighted in promotion and tenure decisions at their institution. An analysis of the responses showed that CMS members did not use the “Other” category, so it was eliminated from further analysis. The results for the question appear in Table 6.

From an examination of Table 6 it is quite clear that there is a relationship between institution type and the weight placed on each of the three categories typically considered for promotion and tenure. For example, the average percent given to the teaching category increases systematically from high research activity institutions to special focus institution and in the scholarship/creative activity category the average percent decreases systematically. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to compare the type of institution and the mean percentage for teaching, scholarship/creative activity, and service. The multivariate result was significant (Wilks’ Lambda = .710, F = 35.27, df = 15, p < .001) indicating a difference in the type of institution and weight given to the criteria. Univariate analyses conducted for each of the three evaluation categories were all statistical significant (Teaching: F = 51.22, df =5, p < .001; Scholarship/Creative Activity: F = 84.26, df = 5, p < .001; Service: F = 20.3, df = 5, p < .001) confirming that the weighting of each of the three traditional criteria is different for promotion and tenure decisions for music faculty members at different types of institutions.

From an examination of Table 6 it is quite clear that there is a relationship between institution type and the weight placed on each of the three categories typically considered for promotion and tenure. For example, the average percent given to the teaching category increases systematically from high research activity institutions to special focus institution and in the scholarship/creative activity category the average percent decreases systematically. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to compare the type of institution and the mean percentage for teaching, scholarship/creative activity, and service. The multivariate result was significant (Wilks’ Lambda = .710, F = 35.27, df = 15, p < .001) indicating a difference in the type of institution and weight given to the criteria. Univariate analyses conducted for each of the three evaluation categories were all statistical significant (Teaching: F = 51.22, df =5, p < .001; Scholarship/Creative Activity: F = 84.26, df = 5, p < .001; Service: F = 20.3, df = 5, p < .001) confirming that the weighting of each of the three traditional criteria is different for promotion and tenure decisions for music faculty members at different types of institutions.

In many ways the pattern of criteria for music faculty members’ tenure decision looks similar to the promotion and tenure criteria for other faculty members across campus. The similarities seem to be underscored when the data reported is broken down by institution type. For example, as previous researchers (Nadler, 1999) have reported, different types of institutions emphasize different components of the three traditional areas on which faculty members are evaluated, teaching, scholarship/creative activity, and service. We found that to be true also for music faculty from the data provided by CMS members who responded to the survey. Our analysis shows that CMS members perceive differences in the use of promotion and tenure criteria that were statistically significant across institution type in a pattern that mimics campus wide results, with scholarship and creative activity prioritized at doctoral granting institutions and teaching being weighed most at baccalaureate, associate degree, and special focus institutions.

Teaching

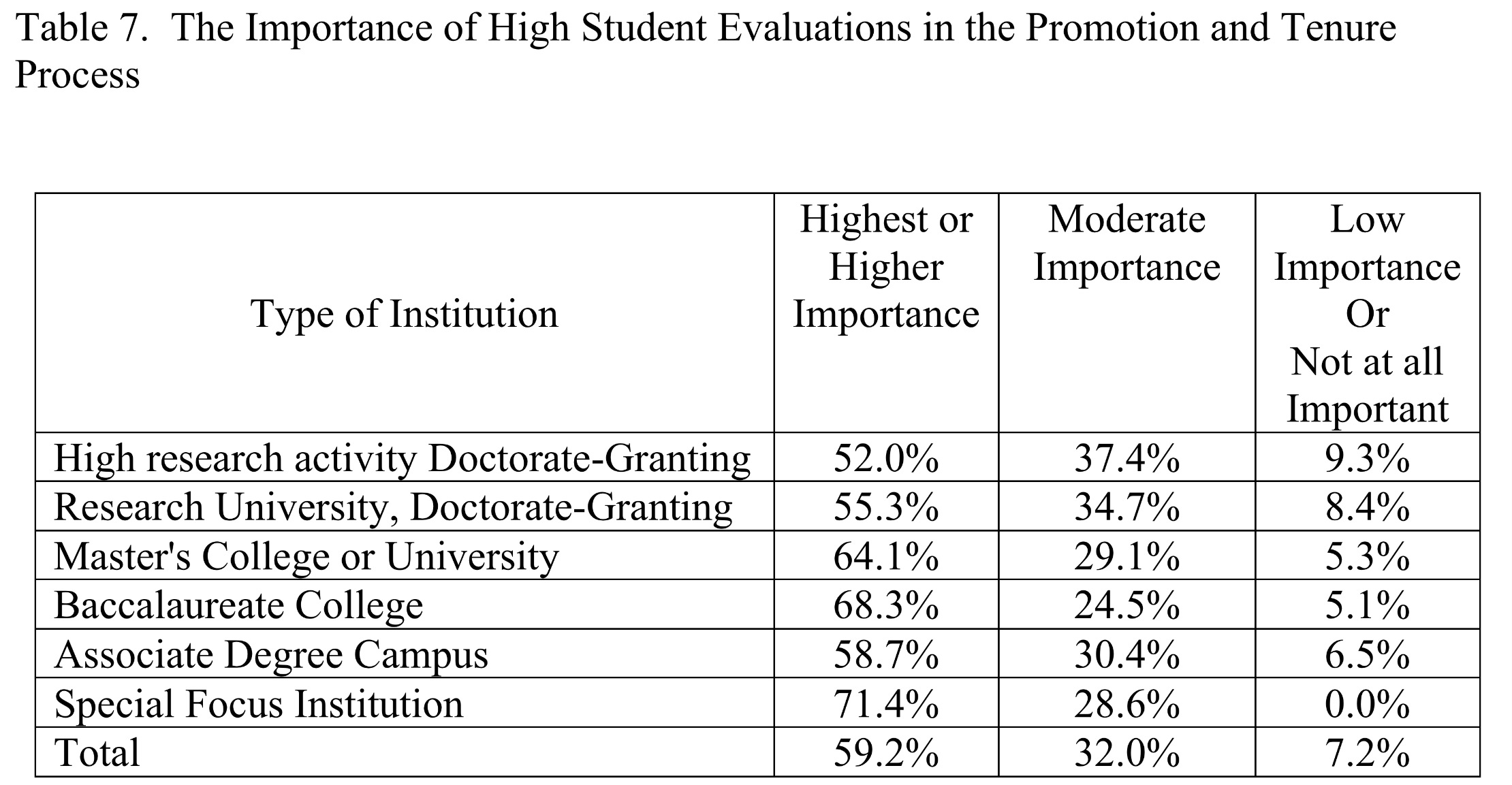

Related to how the traditional evaluative criteria for promotion and tenure are viewed is the kind of documentation candidates are asked to provide or that is gathered by others to assess the candidate. The results of the survey provided information on how student evaluations are viewed at CMS members’ institutions. The results appear in Table 7.

Table 7 shows that student evaluations are perceived to be important in the promotion and tenure process in general, but are thought to be somewhat less important at research universities. The data in Table 7 were analyzed with a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 59.31, df = 25, p < .001) indicate the importance of student evaluations in the promotion and tenure process is significantly different across institutional type.

Table 7 shows that student evaluations are perceived to be important in the promotion and tenure process in general, but are thought to be somewhat less important at research universities. The data in Table 7 were analyzed with a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 59.31, df = 25, p < .001) indicate the importance of student evaluations in the promotion and tenure process is significantly different across institutional type.

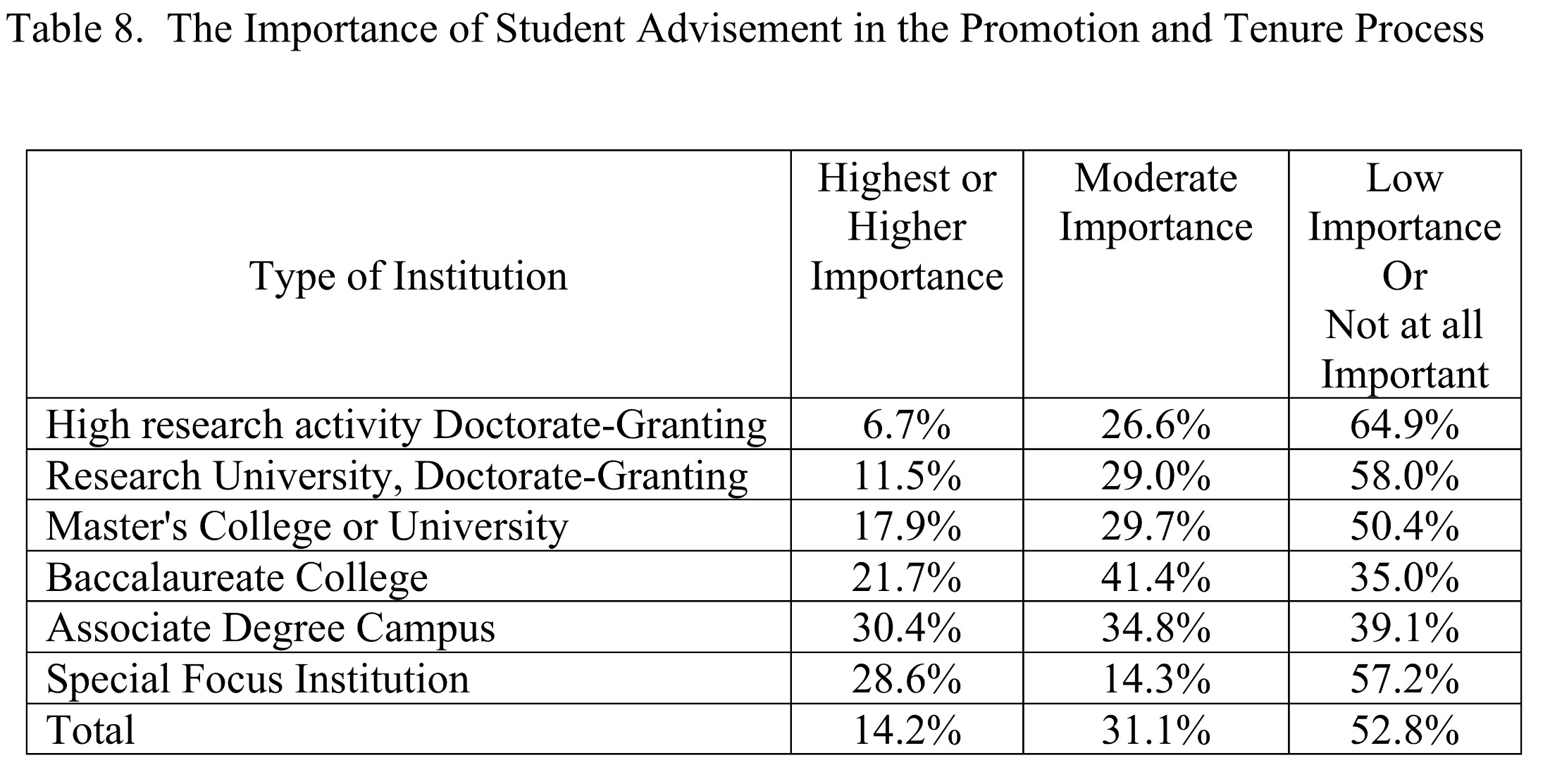

One responsibility of music faculty members that is likely to be related to teaching is student advisement. It may be considered in the teaching or service category when evaluating junior faculty for promotion and tenure. CMS members were asked how important faculty members’ success in student advising was to the promotion and tenure review process at their institution. The results appear in Table 8.

Table 8 shows that student advising is not considered to be important in the promotion and tenure process in general, with more than half of the respondents (52.8%) rating it as low importance or not important at all. However, advising is viewed as somewhat more important at baccalaureate, associate degree and special focus institutions. The data in Table 8 were subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 133.52, df =25, p < .001) indicate that the importance of student advising in the promotion and tenure process differed significantly across institutional type.

Table 8 shows that student advising is not considered to be important in the promotion and tenure process in general, with more than half of the respondents (52.8%) rating it as low importance or not important at all. However, advising is viewed as somewhat more important at baccalaureate, associate degree and special focus institutions. The data in Table 8 were subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 133.52, df =25, p < .001) indicate that the importance of student advising in the promotion and tenure process differed significantly across institutional type.

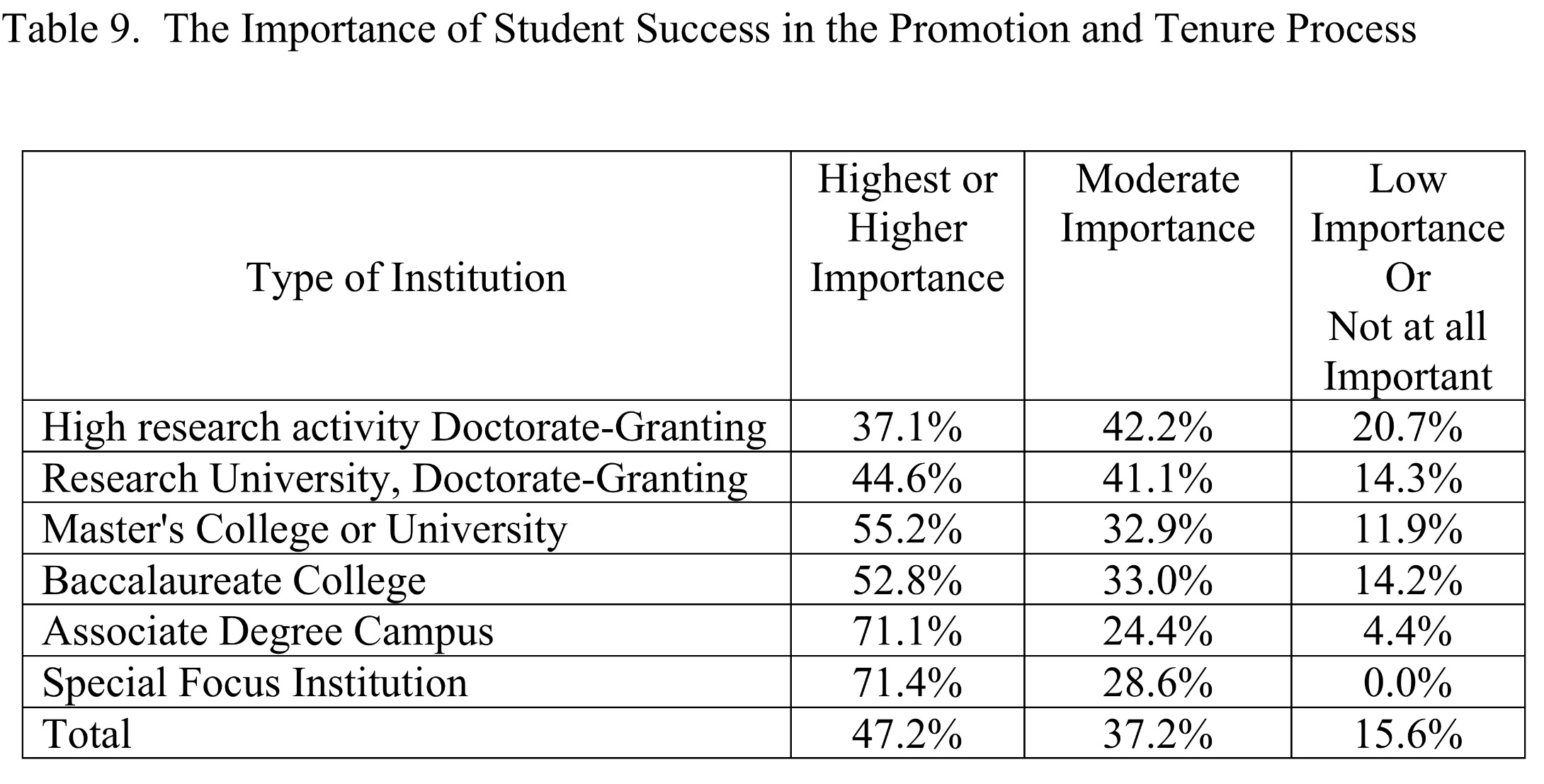

As colleges and universities are increasingly being asked by different government agencies to demonstrated the “value added” of their degrees, many institutions are placing additional emphasis on student achievement or success (Liu, 2011). To better understand the importance of student success in the promotion and tenure process we asked CMS members to rate students’ success. Table 9 presents the results for student success.

A review of the data in Table 9 shows that student success is perceived to be most important in the promotion and tenure process in associate degree and special focus institutions and least important in doctoral granting institution. The data in Table 9 were analyzed using a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 51.74, df =10, p < .001) indicate that the importance of student success in the promotion and tenure process is significantly different across institutional type.

A review of the data in Table 9 shows that student success is perceived to be most important in the promotion and tenure process in associate degree and special focus institutions and least important in doctoral granting institution. The data in Table 9 were analyzed using a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 51.74, df =10, p < .001) indicate that the importance of student success in the promotion and tenure process is significantly different across institutional type.

It appears also that the documentation and importance of teaching-related factors used in promotion and tenure decisions are similar for music faculty and for other faculty members. Our results show that high student evaluations are more important in the promotion and tenure process at baccalaureate and special focus institutions than they are at institutions that award doctorates. In addition, while student advisement is generally not viewed as important in the promotion and tenure process for music faculty members, it is viewed as less important at doctoral granting institutions and more important at baccalaureate, associate and special focus institutions.

Student evaluations, student advisement, and the success of students all are likely to be considered in the teaching category for promotion and tenure. In addition, student success is also being emphasized by government agencies as an index of accountability. Once again, our data show that student success is most important at special focus and associate degree campuses, while viewed as less important in the promotion and tenure process at doctoral granting institutions.

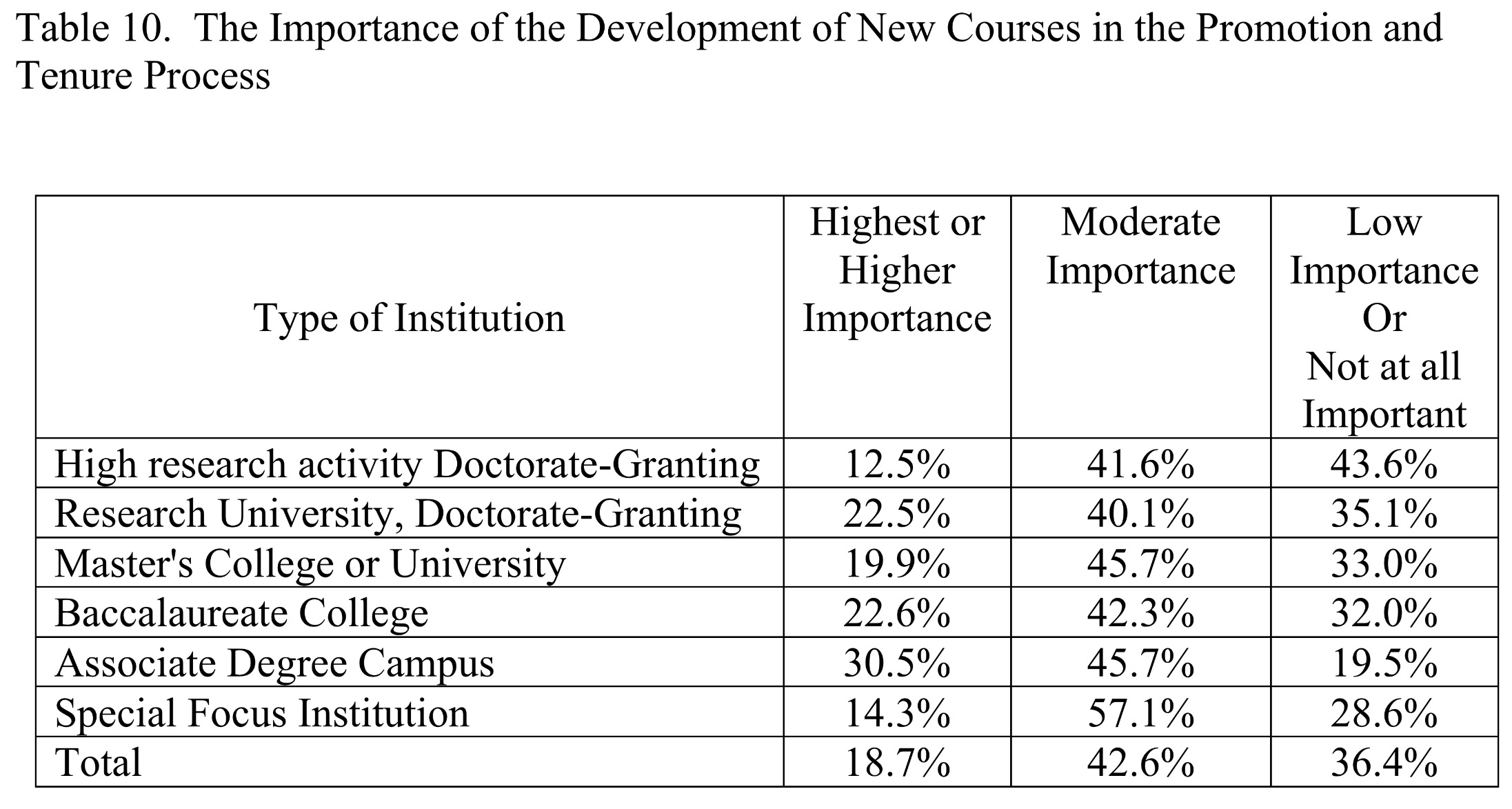

The development of new courses/curriculum at some institutions may be viewed as an important component of a music faculty members’ teaching portfolio. The survey included a question that asked CMS members about how the development of new courses was viewed as a factor in promotion and tenure decisions. The results appear in Table 10.

Table 10 shows that the development of new courses is perceived to be much less important than student evaluations in the promotion and tenure process across different institution types. The development of new courses is perceived to be less important at research universities than at other types of institutions. The data in Table 10 were subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 50.33, df = 25, p < .002) indicate that there is a significant difference in how developing new courses is valued across institutional type.

Table 10 shows that the development of new courses is perceived to be much less important than student evaluations in the promotion and tenure process across different institution types. The development of new courses is perceived to be less important at research universities than at other types of institutions. The data in Table 10 were subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 50.33, df = 25, p < .002) indicate that there is a significant difference in how developing new courses is valued across institutional type.

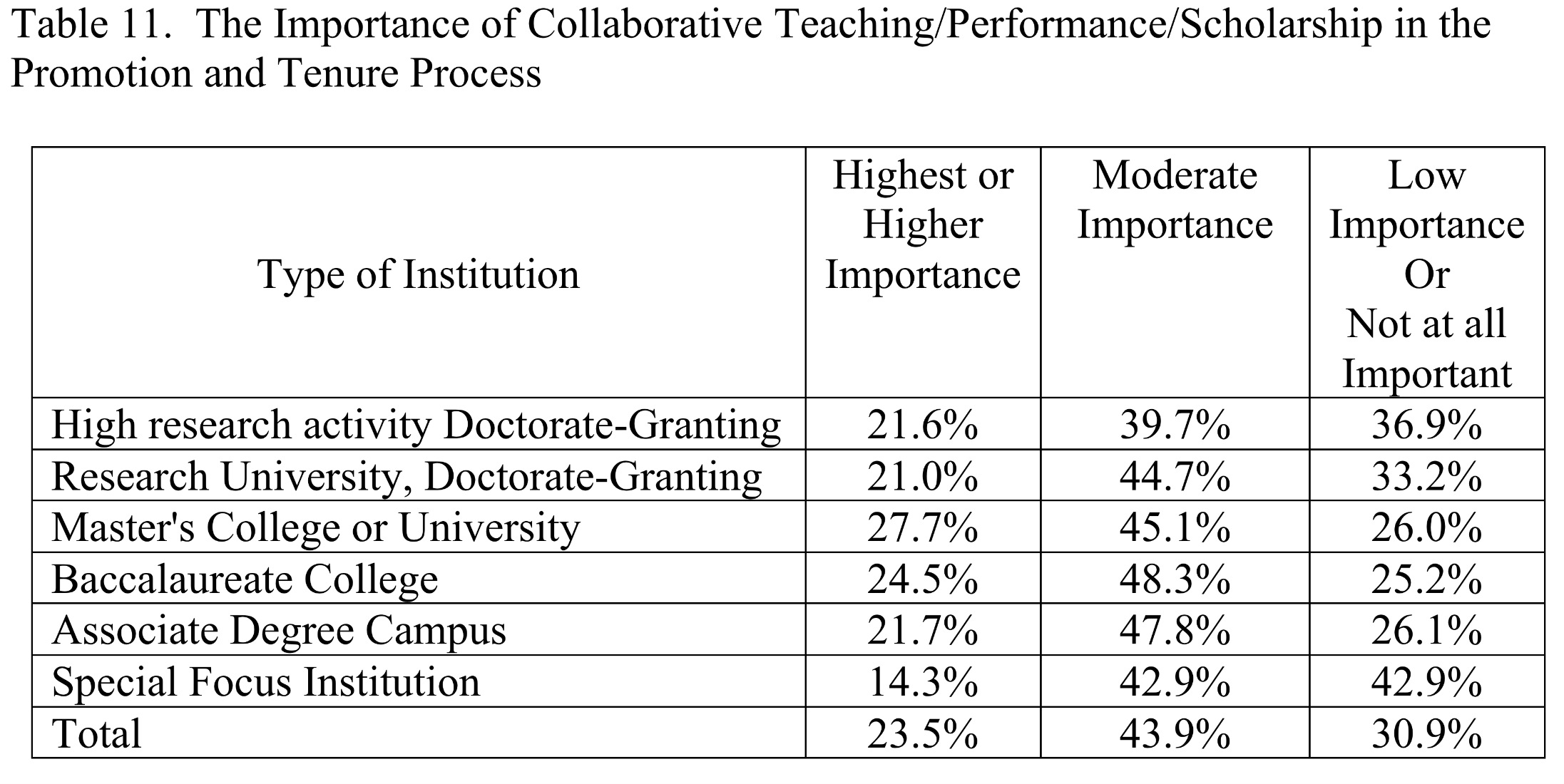

Collaborative teaching, performance and/or scholarship are also encouraged at some institutions and may be viewed as an important component of a music faculty member’s tenure dossiers. CMS members were asked how collaborative work was viewed as a factor in promotion and tenure decisions. The results appear in Table 11

An examination of the results in Table 11 indicate that collaborative work is viewed as slightly more important than the development of new courses in the promotion and tenure process in general, and is thought to be somewhat less important at research universities. The data in Table 11 were once again subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The result of the analysis (Pearson Chi-square = 41.84, df = 25, p < .019) does indicate that the importance of collaboration in the promotion and tenure process differs significantly across institutional types.

An examination of the results in Table 11 indicate that collaborative work is viewed as slightly more important than the development of new courses in the promotion and tenure process in general, and is thought to be somewhat less important at research universities. The data in Table 11 were once again subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The result of the analysis (Pearson Chi-square = 41.84, df = 25, p < .019) does indicate that the importance of collaboration in the promotion and tenure process differs significantly across institutional types.

For music departments administratively housed with other disciplines, as in an arts and sciences college, interdisciplinary teaching and/or scholarship may be encouraged and supported and consequently may also be considered as a factor for promotion and tenure. A question on the survey addressed this issue. The results showed that 19.1% of faculty report that interdisciplinary work is viewed as highest or higher importance, 40.9% viewed the work as moderately important, and 38.3% of CMS members thought interdisciplinary teaching or scholarship to be of low importance or not at all important in the promotion and tenure process at their institution. However, these results did not vary significantly by institutional type (Pearson Chi-square = 26.09, df =25, p < NS), as did the several of the other factors we examined.

At some institutions, curriculum development, including creating new courses may be viewed as important work for music faculty. Our analysis revealed that in general the development of new courses was not viewed as important in the promotion and tenure evaluation, although, it was viewed as more important at institutions focused on undergraduate instruction. Similarly collaborative teaching and/or scholarship and creative activity also may be viewed as important work at some institutions. The survey results indicated that collaboration was viewed as somewhat more important than developing new courses and did differ significantly across institution type with doctoral granting institutions placing less importance on collaboration than other types of institutions. It also may be that for music departments administratively clustered with other arts and humanities departments that interdisciplinary work is encouraged. Our analysis shows that it is viewed in a similar pattern as is collaborative teaching and/or the development of new courses, but the importance of interdisciplinary work did not differ by institutional types as did other did the other factors.

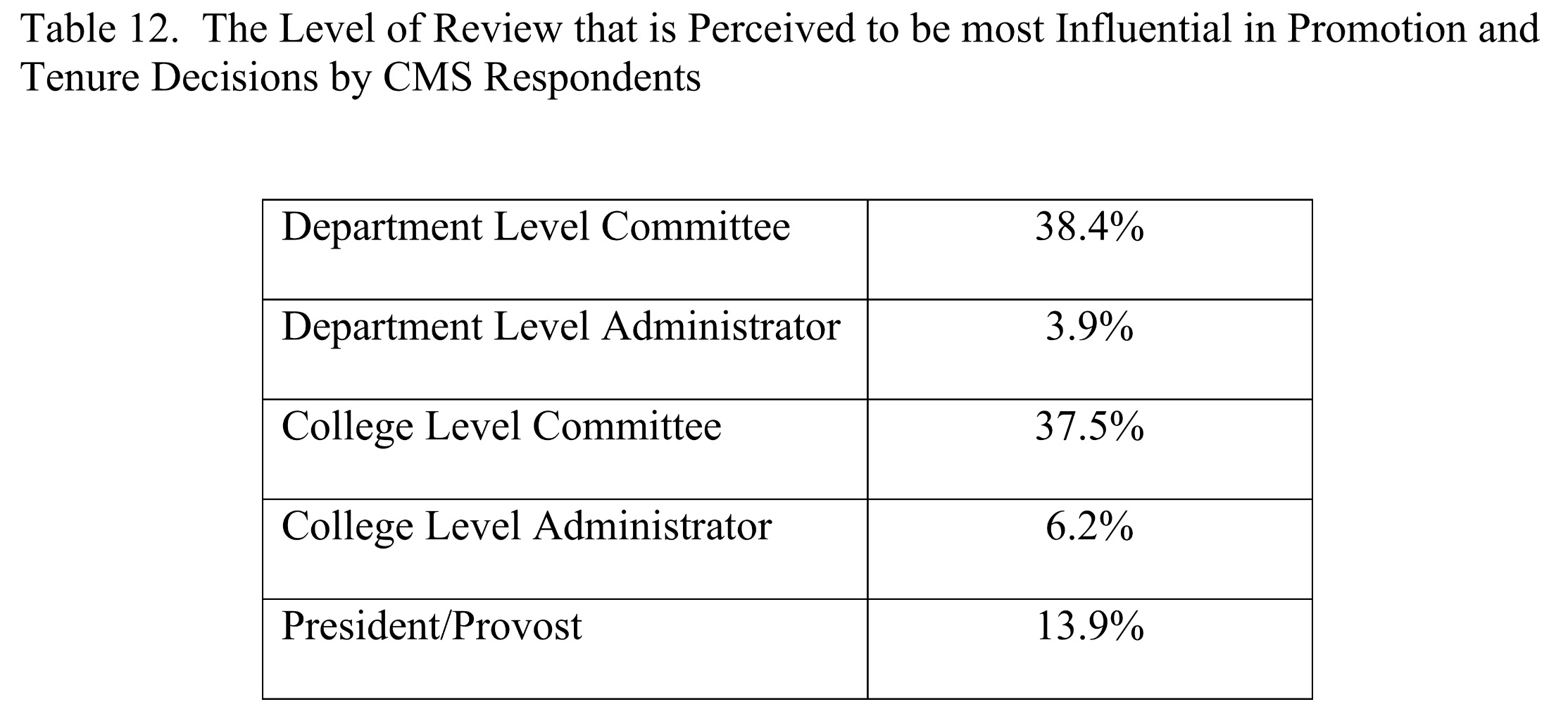

Typically, several different faculty committees and administrators at different institutional levels such as, department, college/school, and university make promotion and tenure decisions. What particular level and type of the decision-making process is most influential in the decision may very well be institutionally idiosyncratic. To examine this, we asked CMS members, “What level is the most influential in the ultimate tenure decision?” Table 12 reveals that committees, both at the department and college level are thought to be the most influential in the process. Presidents/Provosts also are viewed as important in the decision - a few respondents wrote-in the Board of Trustees.

Creative Activities. One of the challenges arts faculty members may confront in the promotion and tenure process is how their creativity/performance activities are to be evaluated. How creative activity is managed during promotion and tenure is of particular concern to many music faculty members whose primary contributions to their profession are in this area. One strategy to assist in the process is to have a clearly defined policy regarding creativity and performance. We asked CMS members about the promotion and tenure policy regarding creativity and performance activities at their institution. Almost half (47.4%) indicated that the creative activities are defined clearly in a policy. Another 25.1% responded that creative activities are generally defined but not clear in the policy and a relatively small number (3.1%) indicated that creative activities are not clearly defined in policy. About 20% did not answer the question, possibly indicating a lack of policy. A small number responded with statements like, “They are clearly defined in policy but not followed by committees.” Our analysis shows about three-quarters of CMS member’s institutions have a policy in place and about half believe that creative activities are defined clearly in the policy.

Creative Activities. One of the challenges arts faculty members may confront in the promotion and tenure process is how their creativity/performance activities are to be evaluated. How creative activity is managed during promotion and tenure is of particular concern to many music faculty members whose primary contributions to their profession are in this area. One strategy to assist in the process is to have a clearly defined policy regarding creativity and performance. We asked CMS members about the promotion and tenure policy regarding creativity and performance activities at their institution. Almost half (47.4%) indicated that the creative activities are defined clearly in a policy. Another 25.1% responded that creative activities are generally defined but not clear in the policy and a relatively small number (3.1%) indicated that creative activities are not clearly defined in policy. About 20% did not answer the question, possibly indicating a lack of policy. A small number responded with statements like, “They are clearly defined in policy but not followed by committees.” Our analysis shows about three-quarters of CMS member’s institutions have a policy in place and about half believe that creative activities are defined clearly in the policy.

Another factor that is an important consideration for musicians’ promotion and tenure decisions is how non-musicians view their creative activities. The survey included the question, “How is creative activity evaluated by non-musicians at your institution? Almost half of the respondents (47.4%) indicated, “It is up to the candidate to express their qualifications and achievements to non-specialists.” Another quarter (25.1%) of those surveyed selected the response, “It is up to the committee to determine the significance of the candidate’s qualifications and achievements,” while 4.1% indicated that both approaches were used. On this question, many respondents (10.3%) wrote in comments rather than using the supplied responses. Common write-in responses were, “Narrative is written in supporting statements by mentor and department chair.”; “There is usually a representative from the Arts Division on the deciding committee.”; and “Creative activity is clearly defined in the Faculty Handbook.”

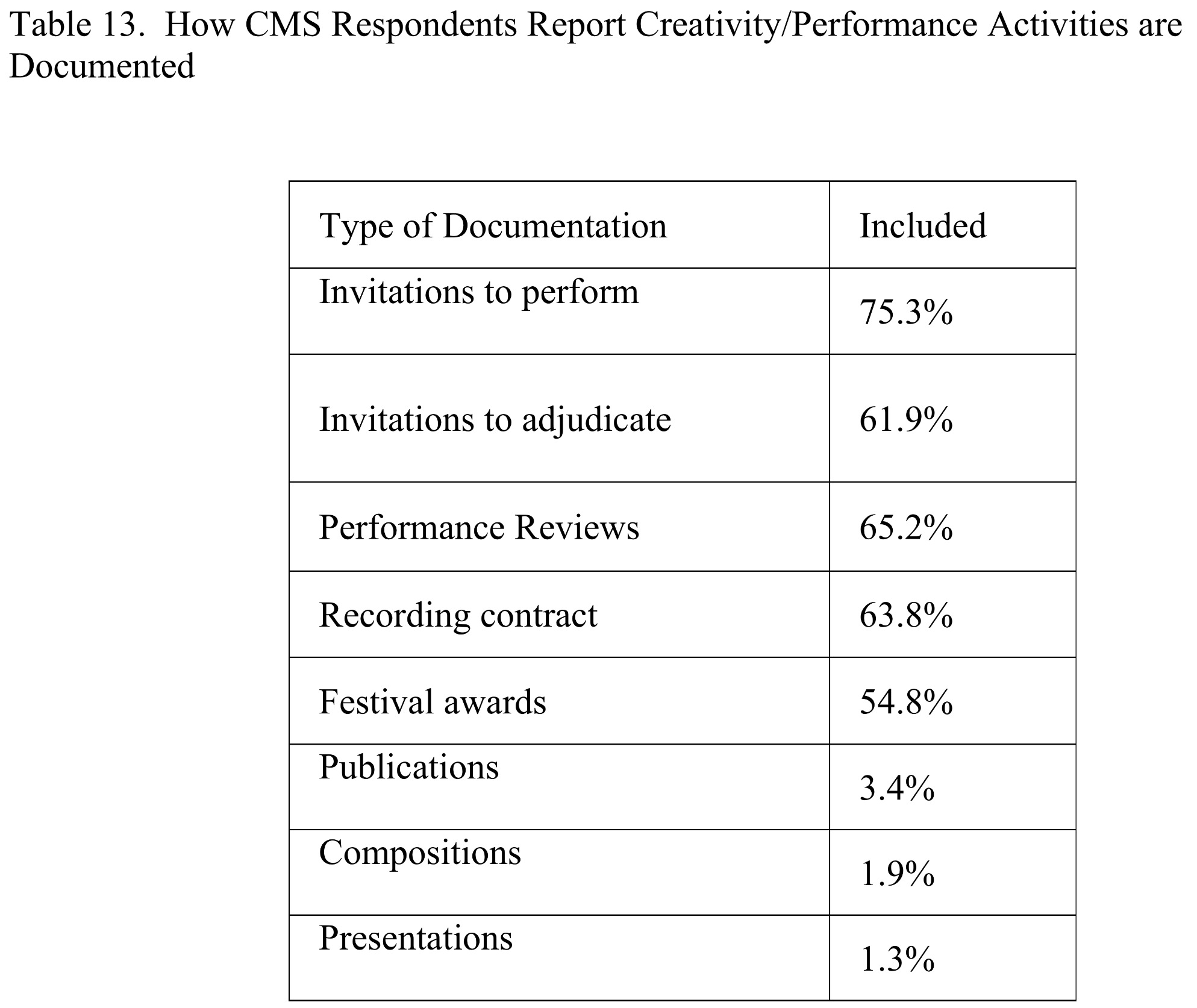

When faculty committees and administrators review promotion and tenure dossiers of music faculty, how is a candidate’s creative/performance activity typically documented? CMS members reported that they provided a variety of materials to document their creative activities. Items that CMS members’ reported are used at their institution to document creative/performance activity appear in Table 13.

Among the most frequently mentioned documents were invitations to perform and adjudicate, as well as performance reviews and recording contracts.

Among the most frequently mentioned documents were invitations to perform and adjudicate, as well as performance reviews and recording contracts.

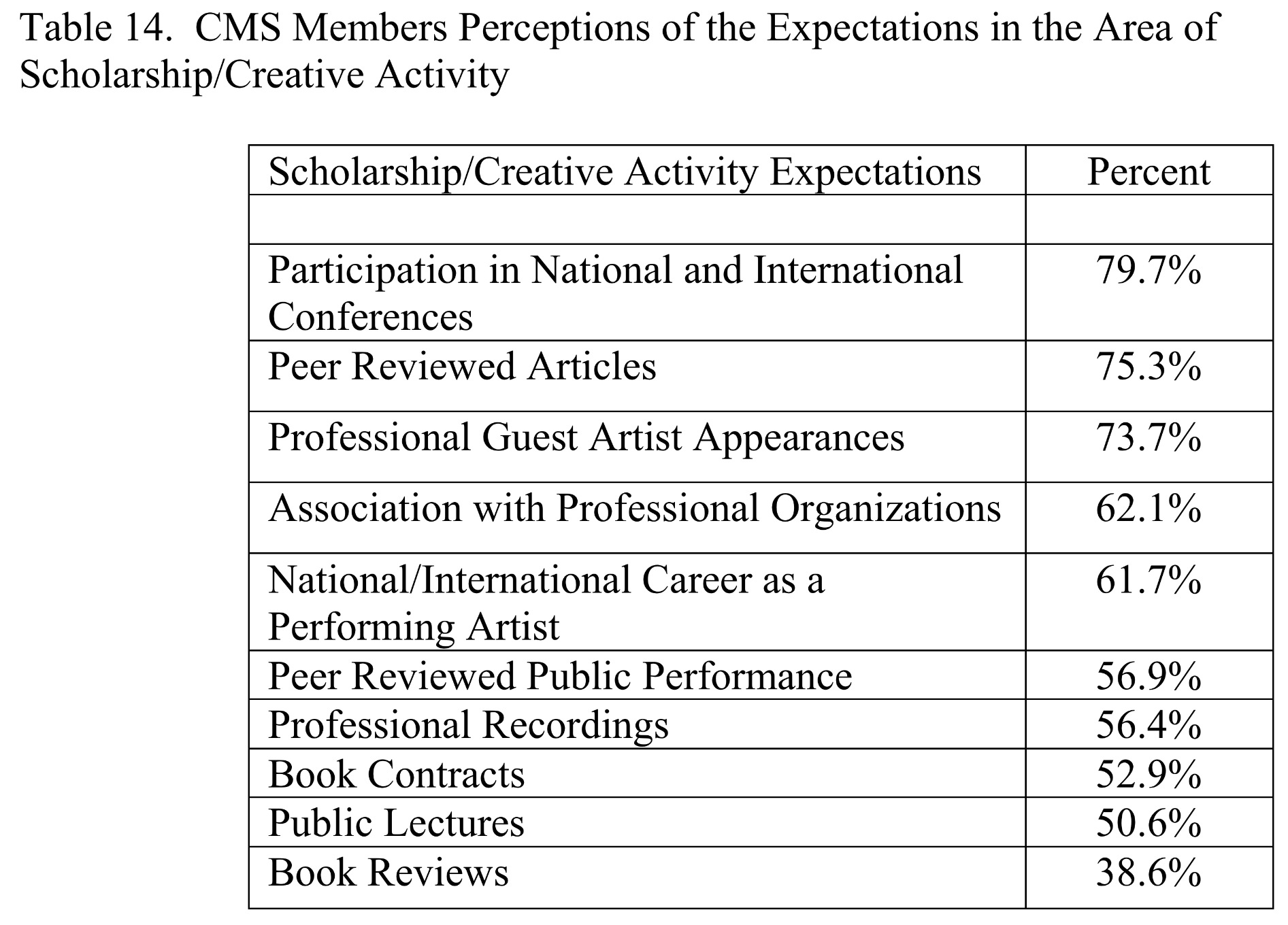

In a similar but broader question, CMS members were also asked, “Which of the following are expectations at your institution in the area of scholarship/creative activity?” Table 14 presents the results.

The results reported in Table 14 reveal that there is considerable agreement on the expectations for research and creative activity, with only one item, Book Reviews, being cited by less than half of the respondents. Similar to their cross-campus colleagues, participation in conferences and publishing in peer-reviewed journals are important activities that document scholarship.

The results reported in Table 14 reveal that there is considerable agreement on the expectations for research and creative activity, with only one item, Book Reviews, being cited by less than half of the respondents. Similar to their cross-campus colleagues, participation in conferences and publishing in peer-reviewed journals are important activities that document scholarship.

Music faculty members are also likely to have a perspective on how creative and performance activities contribute to their individual or department’s status. The survey included the question, “Indicate how creative activity is regarded at your institution.” Survey responses showed that a majority (52%) of the respondents thought that performance and creative activity, “Contributes to the reputation of the department and the enhancement of the departmental mission,” while only 10.8% thought that it primarily “Benefits the individual.” Approximately 28% responded that performance and creative activity contributed both to the department and the individual. These results seem to hint at a more collegial rather than individual perspective on the creative activities of faculty members. CMS members also reported that 79.1% of their institutions consider scholarly or creative work that is published online to be appropriate evidence for promotion and tenure consideration.

Service. Service is one of the components typically considered in the promotion and tenure process for music professors. CMS members were asked to identify what types of service were expected at their institutions. A large number of respondents (89.5%) indicated that department service was expected. A slightly lower number (86.1%) responded that college service was also expected. Still a smaller number (61.1%) indicated that university service was also expected. A little less than four percent (3.7%), who were mostly at graduate degree granting institutions, mentioned community service as an expectation and only a small number (2.4%), who were exclusively from doctoral granting institutions, responded that professional service was expected. A chi-square test of homogeneity was used to analyze the results, which show significant differences (Pearson Chi-square = 229.19, df =25, p < .001) in the type of service expected across types of institutions.

Overall, service is viewed as the least important of the traditional categories for promotion and tenure for music faculty members, which parallels how it is viewed across campus (Alshare, Wenger, & Miller, 2007), yet our data show that it is more important on some campuses than others. Committee service, both at the department and college level, seems to be expected, but only doctoral granting institutions appear to expect professional service.

Occasionally, the promotion and tenure committees are charged with reviewing candidates who might be characterized as atypical, i.e., not satisfying the usual criteria for promotion and tenure. CMS members were asked if their institution’s tenure process was broad enough to accommodate such candidates. These data were examined by institution type. Overall, a clear majority (61.2%) responded, “Yes,” with 35.2% of the responses being “No.” The data were then subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 13.77, df =10, p =NS) indicate that promotion and tenure policies that accommodate atypical candidates were distributed somewhat evenly across institutional category or type.

Mentoring

As previously stated, mentoring is an important aspect of developing junior faculty members, but can also be problematic (Hobson, 2012; Iversen et al., 2014). The survey sought to obtain information about the mentoring process in departments and schools of music. The first set of questions examined the process and availability of mentoring.

CMS members were asked, “What type of group mentoring opportunities are available at your institution?” There appear to be many opportunities for music faculty to participate in some group mentoring. More than one-third (38.3%) said that campus-wide workshops were available. Approximately, 17.5% responded that there were both campus-wide and college level mentoring workshops available, while 8.1% indicated that there were both campus wide and department level workshops. Another 24.4% indicated that just college level workshops were offered and not quite ten percent (9.9%) responded that there were only departmental level workshops. Only 1.7% of the respondents reported that they had no access to mentoring workshops.

While attending workshops focused on promotion and tenure is helpful to junior faculty, individual mentoring has been shown to be more effective than attending workshops (Alexander, 1992). CMS members were asked how engaged are the tenured faculty members in the process of mentoring junior faculty members, either officially or unofficially. They responded on a 5-option Likert scale (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree). The average response was 3.02, just slightly above a neutral response, suggesting that there are some departments (37.5%) who have tenured faculty quite engaged in mentoring, but there are also virtually an equal number of departments (33.4%) whose tenured faculty are not engaged in mentoring. For junior faculty musicians working in higher education, mentoring programs seem as well established as they are for faculty members in other disciplines (Morrison et al., 2014). Group mentoring programs appear to be available for virtually all music faculty members. On the other hand, the picture for individual mentoring opportunities seems to be less clear, with about one-third of the respondents reporting that the tenured faculty at their institution were very engaged in mentoring and a third of those reporting indicating that tenured faculty members in their departments were not engaged in mentoring.

CMS members were also asked who mentored them. The most frequent response was a senior faculty member from their department (34.7%). The Department Chair was the second most frequent at 25.1%, followed by a faculty member outside of their department (15.3%) and other arts department faculty (9.9%). More than three-quarters (76.3%) of the respondents reported receiving mentoring from more than one individual, although 14.3% of the respondents indicated that they did not receive individual mentoring.

One factor that may affect the involvement of more senior music faculty members’ willingness to mentor junior faculty members is if mentoring is encouraged or rewarded. Of the CMS members who responded to this question about half (51.5%) reported that mentoring by senior faculty was moderately valued, 20.5% indicated the mentoring by senior faculty was highly valued on their campus, and slightly more than one-quarter (25.4%) reported that mentoring was not valued. The data were examined to see if the valuing of mentoring was related to institution type. The data were subjected to a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 10.60, df =15, p = NS) indicate that the valuing of mentoring was distributed somewhat evenly across institutional category or type.

Institutional Qualities

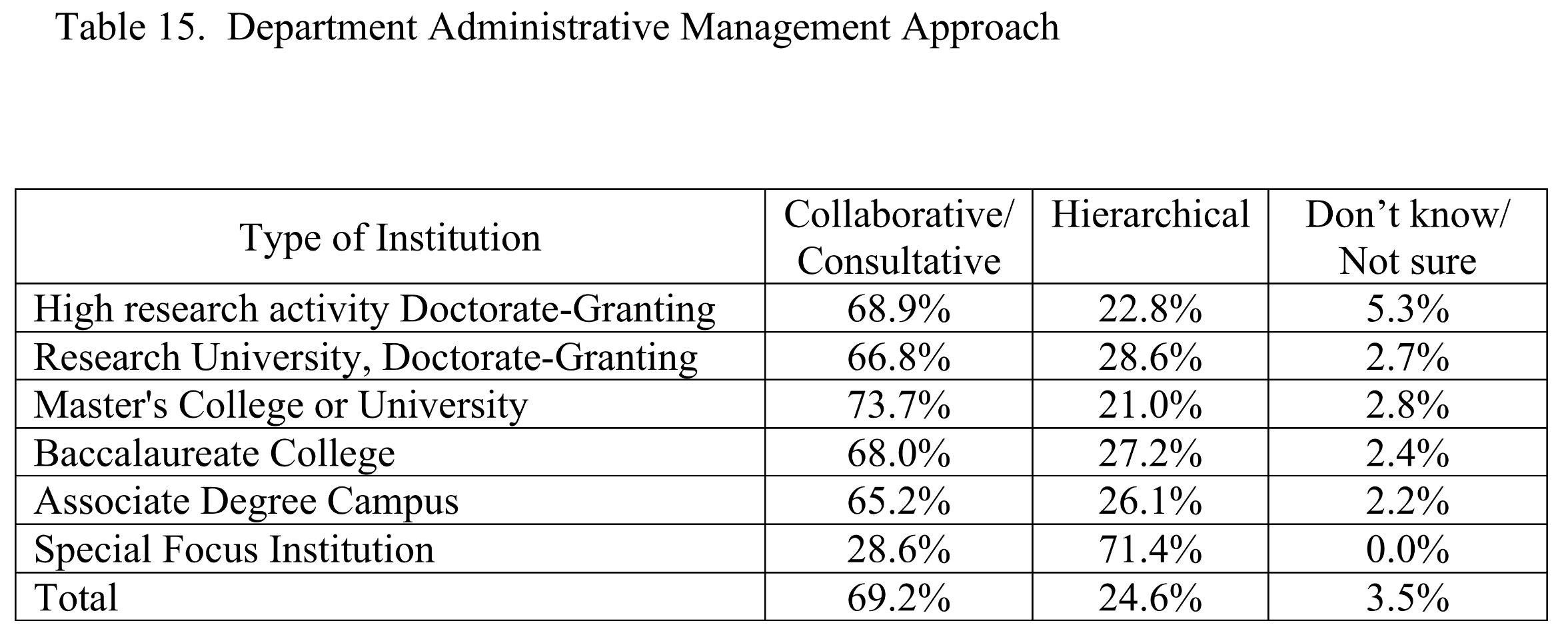

Previous research (Alshare, Wenger & Miller, 2007) suggests that institutional environment, such as the administrative management style, may influence promotion and tenure decisions. It seems reasonable to assume that a variety of management approaches are practiced in schools and departments of music. Several questions on the survey examined the management style at different levels of institutions where CMS members were employed. The results can be seen in Table 15.

Clearly for most music departments the administrative management style used is a collaborative/consultative approach. The exception to this generalization is the music special focus institution, where the more common management approach is hierarchical. The data in Table 15 were analyzed using a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 25.74, df =15, p = .041) indicate that the department management styles were significantly different across the different types of institutions. The effect appears primarily due to the difference of the special focus institutions from the other institutional types.

Clearly for most music departments the administrative management style used is a collaborative/consultative approach. The exception to this generalization is the music special focus institution, where the more common management approach is hierarchical. The data in Table 15 were analyzed using a chi-square test of homogeneity. The results (Pearson Chi-square = 25.74, df =15, p = .041) indicate that the department management styles were significantly different across the different types of institutions. The effect appears primarily due to the difference of the special focus institutions from the other institutional types.

The management approach used at the college level of CMS members revealed a very different pattern from the one observed at the department level. College-level administrative management styles were described predominately as hierarchical, with a majority of responses (57.6%) selecting that descriptor. Only 32.3% described their college level management as collaborative/consultative. An analysis of the data reveal there were not significant differences (Pearson Chi-square = 23.21, df =15, p = NS) in the college level administrative management style across the different types of institutions.

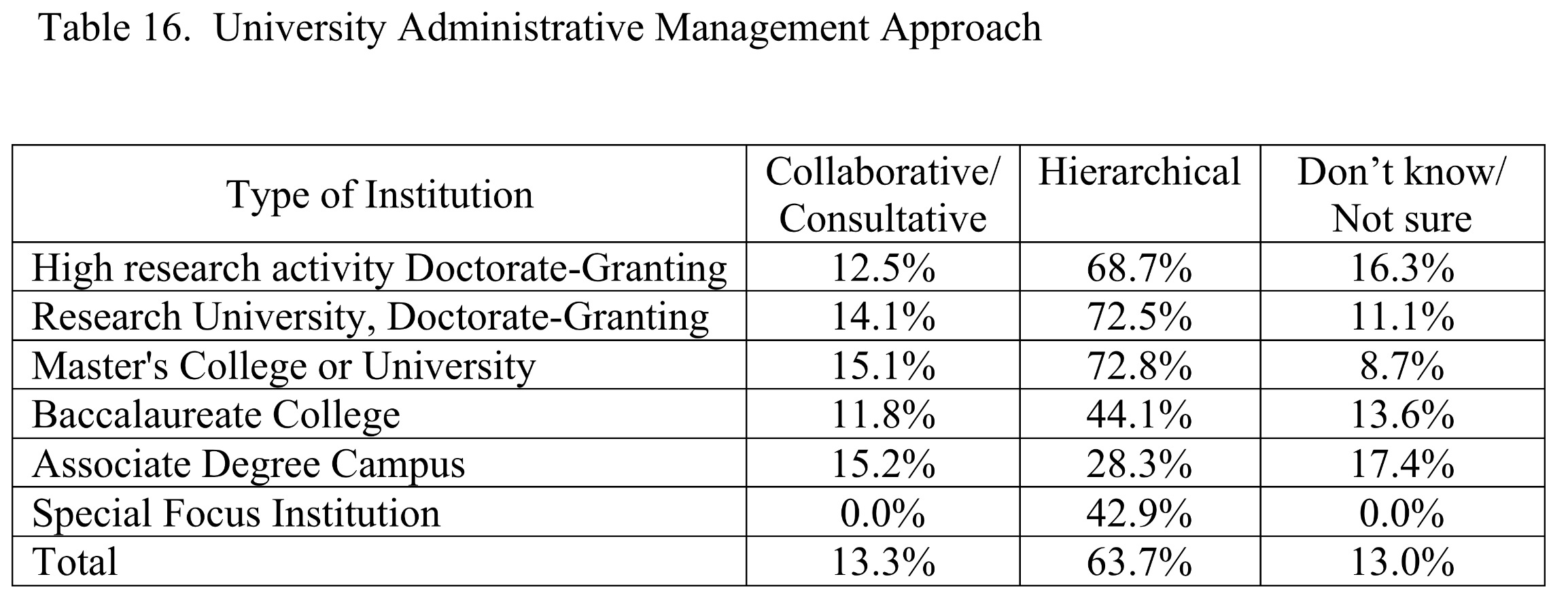

The university management approach was less uniformly hierarchical than was anticipated, although it is still more hierarchical than at the college level. The results appear in Table 16. A larger portion of respondents at baccalaureate colleges (30.5%), associate degree campuses (39.1%) and special focus institution (57.1%) did not answer this question. We assume because those institutions do not have university level administrations.

An analysis of the results in Table 16 showed that there was a significant difference in the university administrative management approaches used at different types of institutions (Pearson Chi-square = 307.79, df =15, p < .001). Most CMS members described their departments’ approach to management as collaborative, with the exception of special focus institutions, while the college level administrative style was mostly characterized as hierarchical. Music faculty members described universities’ administrative approaches as somewhat more hierarchical than college level administration.

An analysis of the results in Table 16 showed that there was a significant difference in the university administrative management approaches used at different types of institutions (Pearson Chi-square = 307.79, df =15, p < .001). Most CMS members described their departments’ approach to management as collaborative, with the exception of special focus institutions, while the college level administrative style was mostly characterized as hierarchical. Music faculty members described universities’ administrative approaches as somewhat more hierarchical than college level administration.

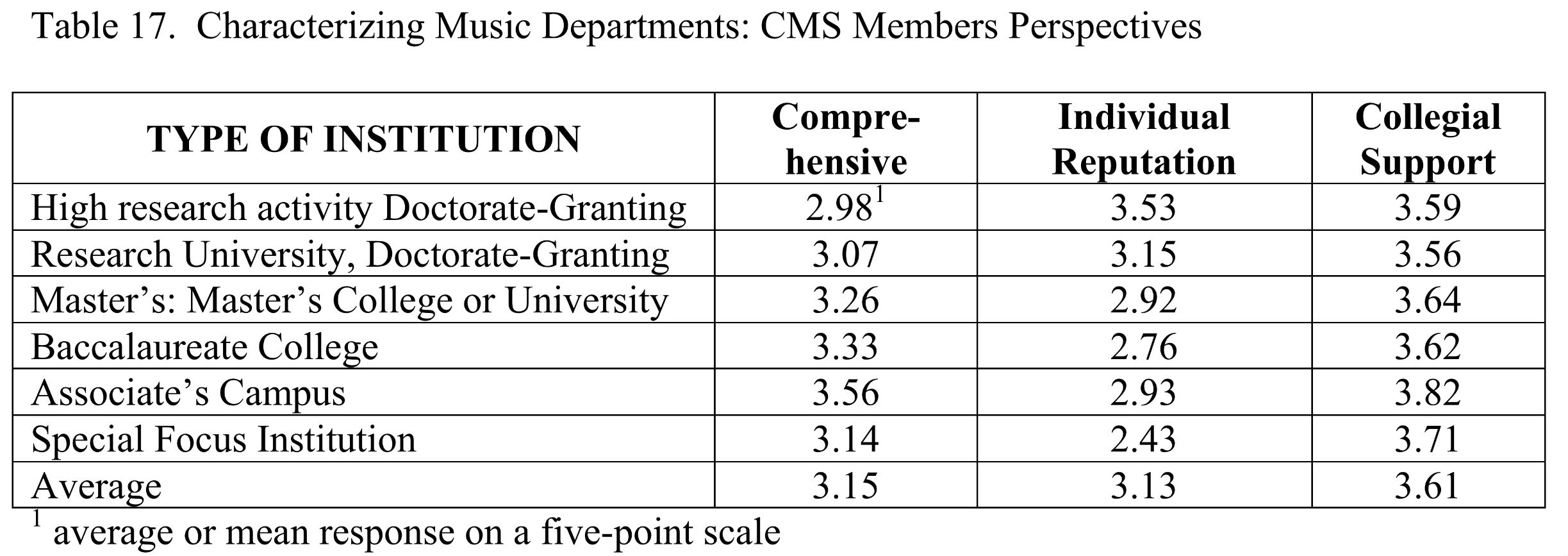

Certainly, a faculty members’ working conditions may have an effect on the promotion and tenure process (Lawrence, etal., 2014). Factors that might affect the work environment can include how the department, as a whole, perceives itself, which is likely related to the perceived mission. Perceptions of a music department's image, similar to a college and/or university's image or branding is increasingly becoming a dimension of higher education (Wæraas & Solbakk, 2009). The qualities of individual music departments, as imagined by their faculty members, may play a role in promotion and tenure decisions, as does the work that an individual faculty member contributes to how the department defines itself. CMS members were asked about factors that characterized their department. Specifically, we asked CMS members, “How well does each of the following characterize your department?: 1) The comprehensive educational and artistic mission of my department exceeds individual success; 2) Individual achievement and reputation are preeminent in defining my department; and 3) An atmosphere of respect and collegial support thrives in my department.” We asked CMS members to rate each of these areas as to how well each might characterize their department on a 5- point Likert scale from a high rating (5) “very much” to a low rating (1) “not a all.” The average rating for each of the three areas appear in Table 17.

An examination of the results in Table 17 show some variations across the different types of institutions for the three dimensions that were used to characterize departments. For the characterization, “The comprehensive educational and artistic mission of my department exceeds individual success,” the ratings are somewhat lower for the doctoral granting institutions than they are for the master’s, baccalaureate, and associate degree colleges. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) indicated that these differences were statistically significant (F = 37.96, df = 5, p < .001). For the characterization, “Individual achievement and reputation are preeminent in defining my department, the pattern is somewhat reverse, with the higher means at the doctoral granting institutions. Once again an ANOVA analysis showed that these differences were statistically significant (F = 149.86, df = 5, p < .001). The last department characterization focused on collegial support, “An atmosphere of respect and collegial support thrives in my department.” A review of the collegial support reveals smaller differences and less of a pattern. An ANOVA analysis indicated that there was not a statistically significant difference between these means (F = 3.28, df = 5, p = NS). Individual faculty achievement was more dominant at research-oriented institutions while department reputation was more dominant at masters, baccalaureate, and associate campuses. Music faculty members described their departments as having an atmosphere of respect and collegial support, regardless of institutional type.

An examination of the results in Table 17 show some variations across the different types of institutions for the three dimensions that were used to characterize departments. For the characterization, “The comprehensive educational and artistic mission of my department exceeds individual success,” the ratings are somewhat lower for the doctoral granting institutions than they are for the master’s, baccalaureate, and associate degree colleges. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) indicated that these differences were statistically significant (F = 37.96, df = 5, p < .001). For the characterization, “Individual achievement and reputation are preeminent in defining my department, the pattern is somewhat reverse, with the higher means at the doctoral granting institutions. Once again an ANOVA analysis showed that these differences were statistically significant (F = 149.86, df = 5, p < .001). The last department characterization focused on collegial support, “An atmosphere of respect and collegial support thrives in my department.” A review of the collegial support reveals smaller differences and less of a pattern. An ANOVA analysis indicated that there was not a statistically significant difference between these means (F = 3.28, df = 5, p = NS). Individual faculty achievement was more dominant at research-oriented institutions while department reputation was more dominant at masters, baccalaureate, and associate campuses. Music faculty members described their departments as having an atmosphere of respect and collegial support, regardless of institutional type.

Conclusions

This study was designed to increase our understanding of factors related to the promotion and tenure process of music faculty members and to examine how collegiality might be a factor in the process. The project was guided by four research questions: a) Is the process for promotion and tenure for music faculty similar to the process for other disciplines across campus? (b) Are the expectations for teaching, scholarship/creative activities and service for music faculty, similar to the expectations in other disciplines? (c) What kind of support systems are available to assist new music faculty members in meeting the expectations for tenure and promotion? and (d) How do faculty members characterize department, college, and university conditions that may influence promotion and tenure decisions such as the administration’s management style and faculty collegiality?

We found that the promotion and tenure process for music faculty is quite similar to the process for other disciplines. For music faculty, the three traditional categories for promotion and tenure, teaching, scholarship/creative activity, and service are applied differently at diverse Carnegie institution types, as they are with faculty members in other disciplines. The documentation expected for music faculty overlaps with what is expected for faculty in other disciplines, but adds materials unique to music creative activities, such as invitations to perform and recording contracts. Regarding the unique qualities that music faculty members often bring to higher education, it is important to note that many institutions have policies in place that define and clarify what is and what counts as creative activity.

In addition, we learned that many institutions with music departments have strategies to help inform non-musician faculty members about appropriate criteria to use when making promotion and tenure decisions about their musician colleagues. Similar to cross-campus colleagues, music faculty members may be expected to participate in national and international conferences and publish in peer-reviewed journals, but alternatively they might appear professionally as a guest artist, have a career, nationally or internationally as a performing artist, have peer-reviewed public performances and produce professional recordings. Online professional work is also viewed as relevant to promotion and tenure decisions.

As in fields outside of music, service activity for music professors is viewed as less important to promotion and tenure considerations as are teaching and scholarship/creative activities. However, service is expected of music faculty, particularly on department and college committees. At doctoral granting research institutions, professional service to the field is also considered somewhat important. The development of new courses, or interdisciplinary teaching and scholarship, or collaborative teaching or scholarship were not viewed as important as more traditional areas of teaching or scholarship and creative activities to promotion and tenure decisions. As is true for a majority of faculty members across campuses, almost all music faculty members have access to group mentoring on their campus, while individual mentoring, either by senior department colleagues or department chairs is much less available, even though senior faculty members, in general, are encouraged to mentor. Lastly, the results suggest that most music departments are perceived to be collegial and that individual productivity is generally viewed as contributing to the department’s status as a group.

Notes

1 Members of the College Music Society Academic Citizenship Committee in 2014 included Hal Abeles, Alicia Doyle, Robert J. Jones, Mary Ellen Junda, David Montano, Anne Patterson, and Anna Song

2 In this paper statistical significance was defined as p < .05

Bibliography

Alexander, J. C., Jr. (1992). Mentoring: On the road to tenure and promotion. ACA Bulletin, 79, 54–58.

Alshare, Khaled A., James Wenger, & Donald Miller. 2007. The role of teaching, scholarly activities, and service on tenure, promotion, and merit pay decisions: deans' perspectives. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 11(1), 53+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.eduproxy.tc-library.org:8080/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&u=new30429&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA166823288&sid=summon&asid=1eb8c7bc32b348d6b6d22e173fe02eeb

Bradley, Deborah, Deanna Yerichuk, Lori-Anne Dolloff, Kiera Galway, Kathy Robinson, Jody Stark & Elizabeth Gould. 2017. Examining equity in tenure processes at higher education music programs: An institutional ethnography. College Music Symposium. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18177/sym.2017.57.sr.11336

Brown, Jeffrey. (2012, June 25). Professor tenure as insurance: what the Wall Street Journal debate missed. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffrey- brown/2012/06/25/professor-tenure-as-insurance-what-the-wall-street-journal-debate- missed/

The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education (n.d.). About Carnegie Classification. Retrieved from http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/.

Chait, Richard (February 7, 1997). Why academe needs more employment options. The Chronicle of Higher Education, B4.

College Music Society (2014). Academic Citizenship Panel Presentation Proposal. College Music Society National Conference. St. Louis, MO. October/November.

Franko, Debra L., Jan Rinehart, Kathleen Kenney, Mary Loeffelholz, Barbara Guthrie, & Paula Caligiuri. 2016. Supporting faculty mentoring through the use of creative technologies. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 5(1), 54–64. doi:10.1108/ijmce-10-2015-0029.

Gillespie, Suzanne M., Loralei L.Thornburg, Thomas V. Caprio, & Annette Medina-Walpole. 2012. Love letters: An anthology of constructive relationship advice shared between junior mentees and their mentors. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 4 (3), pp. 287-289. doi:10.4300/jgme-d-11-00304.1.

Hattie, John and H. W. Marsh. 1996. The relationship between research and teaching: A meta-analysis, Review of Educational Research, 66 (4): 507– 42. doi:10.3102/00346543066004507.

Hobson, Andrew J. (2012), Fostering face-to-face mentoring and coaching. In Sarah Fletcher & Carol Mullen (Eds), The SAGE Handbook of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, SAGE, London, pp. 59-73. doi:10.4135/9781446247549.n5.

Iversen, Amy C., Nigel A. Eady, & Simon C. Wessely. 2014. The role of mentoring in academic career progression: A cross-sectional survey of the academy of medical sciences mentoring scheme. Journal of Research in Social Medicine, 107 (8), 308-317. doi:10.1177/0141076814530685.

Lawrence, Janet H., Sergio Celis, & Molly Ott. 2014. Is the Tenure Process Fair? What Faculty Think. The Journal of Higher Education, 85 (2) copyright © Ohio State University. doi:10.1353/jhe.2014.0010.

Liu, Ou. L. (2011). Value-added assessment in higher education: A comparison of two methods. Higher Education, 61, 445-461. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9340-8.

Metz, Thaddeus. 2011. Accountability in higher education: A comprehensive analytical framework. Theory and Research in Education, 9 (1), 41-58. doi:10.1177/1477878510394807

Morrison, Laurie J., Edmund Lorens, Glen Bandiera, W. Conrad Liles, Liesly Lee, Robert Hyland, Heather McDonald-Blumer, Johane P. Allard, Daniel M. Panisko, Jenny E. Heathcote, and Wendy Levinson. 2014. Faculty Development Committee, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. Impact of a formal mentoring program on academic promotion of department of medicine faculty: a comparative study. Medical Teacher 36 (7), 608-614. doi:10.3109/0142159x.2014.899683.

Nadler, Elsa G. (1999). The evaluation of research for promotion and tenure: An organizational perspective (Order No. 9926706). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304535030). Retrieved from http://eduproxy.tc-library.org/?url=/docview/304535030?accountid=14258

Rice, Eugene, Mary D. Sorcinelli, M.D., & Ann E. Austin. 2000. Heeding new voices: Academic careers for a new generation. New pathways working paper series, inquiry no. 7. Washington, DC: American Association for higher education.

Schrodt, Paul, Carol Cawyer, & Renee Sanders. 2003. An examination of academic mentoring behaviors and new faculty members’ satisfaction with socialization and tenure and pro- motion processes. Communication Education, 52(1), 17–29. doi:10.1080/03634520302461.

Waeraas, Arild., & Marianne Solbakk. 2009. Defining the essence of a university: Lessons from higher education branding. Higher Education, 57(4), 449-462. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40269135 doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9155-z.