In this response, I have nothing particularly critical to provide nor do I have the space to respond to all of the valid and essential questions he asks about business and peace. Those questions set the agenda for conversations that will unfold over a considerable period of time. Instead, my aim is to draw some connections between the work I and others have done in the field of business and peace and connect it to Urbain’s articulation of the issues pertaining to music and peace.

Thus, in the first section, I rely on his themes in exploring music for peacebuilding and connect those themes to the research on business and peace. In Section II, I suggest a structural model that may be helpful in dealing with the inherent ambivalence of both music and business as relates to peace and squarely address how such a structure might approach normative issues. That is, given the fact that both business and music can be used for negative (violent) as well as positive (peaceful) purposes, what are the ethical norms that direct to, well, accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative. Finally, Section III extends some of these themes and structures in an experiment I currently am conducting with my business ethics classes where they are required to identify a piece of music that corresponds to a level of moral development as proposed by, and which I modified, by moral psychologists.

Olivier Urbain’s presence in this special issue and in the conferences pertaining to music, business and peace range beyond being welcome; they are inspiring and validating. To have someone of Urbain’s stature willing to take time, not only for an appearance for a conference, but to engage in ongoing exploration of the possibilities of the topic provides a significant boost to the validity of the topic itself. Of course, there is a reason for why he has that effect. His searching intellect both opens and refines ideas in a way that move any conversation forward and productively. His contribution to this special issue thus calls for our attention.1Urbain, “Business and Music in Peacebuilding Activities: Parallels and Paradoxes” (this issue Symposium 58.3, hereinafter Urbain).

In this response, I have nothing particularly critical to provide nor do I have the space to respond to all of the valid and essential questions he asks about business and peace. Those questions set the agenda for conversations that will unfold over a considerable period of time. Instead, my aim is to draw some connections between the work I and others have done in the field of business and peace and connect it to Urbain’s articulation of the issues pertaining to music and peace.

Thus, in the first section, I rely on his themes in exploring music for peacebuilding and connect those themes to the research on business and peace. In Section II, I suggest a structural model that may be helpful in dealing with the inherent ambivalence of both music and business as relates to peace and squarely address how such a structure might approach normative issues. That is, given the fact that both business and music can be used for negative (violent) as well as positive (peaceful) purposes, what are the ethical norms that direct to, well, accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative.2With apologies to Bing Crosby. https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=accentuate+the+positive+eliminate+the+negative+lyrics&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8 Finally, Section III extends some of these themes and structures in an experiment I currently am conducting with my business ethics classes where they are required to identify a piece of music that corresponds to a level of moral development as proposed by, and which I modified, by moral psychologists.

Five Central Themes

Urbain identifies five basic assumptions in exploring music’s potential for contributing to peace. The first is ambivalence. Indeed, the notion of ambivalence suffuses all of his concern. Music – including beautiful music – can be used for negative purposes. If this is true, then we should be wary of easily assuming that, since music is universal, it provides a neat way to connect people with each other in a constructive, peaceful way.3Urbain. This concern about ambivalence is, of course, not limited to music. Religion is another cultural force that can be a force for some of the most gentle, humanitarian, and inspiring actions human beings have historically enacted as well as some of the most vicious, de-humanizing, and barbaric ones.4Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence and Reconciliation So too can government. Stephen Pinker, whose book, The Better Angels of our Nature, has enjoyed a revival of interest after Bill Gates endorsed it, argues that large governments have beneficially repressed the violence that exited through more decentralized human history;5Pinker, The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. yet, the resources possessed by large governments are essential to produce thermonuclear and chemical weapons.

Olivier nicely sets out the nature of music’s ambivalence and suggests that business shares this issue as well. He is certainly correct. Colonialism, sweatshop labor, insensitive cultural practices, and outright encouragement of war or, in some cases, the perpetration of violence itself, have all been rightly attributed to businesses.6Fort and Schipani, The Role of Business in Fostering Peaceful Societies. Yet, General Electric stepped between the governments of India and Pakistan, when those two countries stood at the nuclear abyss in 1998 and talked them down from their catastrophic precipice.7Friedman, India, Pakistan and G.E. Building on Urbain’s example of the help music provided during the Troubles of Northern Ireland, a company there – Futurways – intentionally comprised its workforce of half Catholics and half Protestants in order to find a way for those people to work together.8Fort and Schipani.

Thus, like music, business shares in this issue of ambivalence just as it does the second assumption Olivier identifies: non-universality. Of course, one can find music in every culture as he indicates. So too, can one find some element of business in every culture. Business might not exist in a contemporary capitalistic sense, but trade and exchanges of goods is also ubiquitous. The same can be said about the practices of business. In some countries, such as China, one does not really “get down to business” until there have been elaborate exchanges of gifts between the parties.9Dunfee and Warren. Those same practices might be characterized as corrupting bribes in other countries, raising questions of whether cultural practices – in business conduct or via musicking – are so different as to undermine any claim to how the universality of trade – and music – provide any beneficial contribution to peace.

The third, obviously, related aspect is musicking itself. As Olivier details in some considerable length, musicking is a participation in the experience of music, whether in terms of performing or listening. This experience, by definition, applies whenever there is music. Some performance is being done and some listening is being done as well. The resulting question then is the ways in which all the participants in musicking are engaging, how they are interpreting, how they are orienting themselves to it, and how they are treated by it. Urbain himself makes the connection to business. There may business, trade, and exchange – just as there is with musicking – but the question is how people are treated in the experience.10Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening.

Next, there is the importance of repetition. Olivier argues that a key to music’s success in fostering peace is repetition. That is, a one-off concert may be fulfilling and inspiring, but it is the repeated interaction of musical engagement that creates an ethos of solidarity. Here too, the analogy to business is very clear. Often when people think of ethical issues in business, they are posed as a (usually intractable) dilemma whereas I have always argued that the key to ethical business conduct is corporate culture and reputation. How does one build corporate culture and reputation? Not through the resolution of a one-off dilemma (though there is certainly nothing wrong with that) but through repeated interactions and conduct that build an ethos of solidarity within the organization and a reputation as well.

Finally, there is notion of music pertaining to being a booster. Music can act as a booster to activities. Music often accompanies religious ceremonies, government celebrations, and sports events. It can add to these moments, promoting solidarity and emotional connection. Thus, as Olivier suggests, it may not be that there is anything inherently good or bad about music per se, but it can have a booster effect on what it is associated with.11Urbain. It may be possible that music can also be beneficial for business as well, an idea I wish to explore below.

Methodological Constructs

Prior to exploring such a boost that music might provide, not just to business, but with respect to a specific way in which music might nudge behavior toward the ethical practices associated with peace, it is worth exploring more directly this lingering issue of a normative orientation to music and business (or another cultural forces) to account the ambivalence that can cause any of these forces to be negative as well as positive.

Normative, Dialectical Models & Multilevel Selection Theory

In resolving the problem of ambivalence, the temptation is to attempt to find a system of ethics that one could use to differentiate between positive and negative actions of a given cultural artifact. Of course, the problem one immediately runs head-on into is the irresolvability of ethical systems. Which one is best? Alasdair MacIntyre captured the question in the title of his book, Whose Justice? Which Rationality?12MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? I would like to suggest that, prior to attempting any such an exhaustive (and likely Sisyphean) project, it may help to consider differing levels of actors. To take a simple example, is the ethical evaluation of relationships between nation-states the same as what would be the case between, say, a husband and wife? To be sure, there are common features: both kinds of relationships thrive on honesty and respect, but there is also a qualitative difference between the kind of relationship in a marriage and that of France and Australia.

At the conference, Scott Shackelford, drawing on the work of Nobel Prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom, introduces a methodological construct called polycentric governance. The notion is that different governance structures are better suited for different times and places. Akin to basic notion of the kind of federalism that argues that some issues are national and some that better handled in the states, polycentric governance proposes that some kinds of problems are better addressed locally, others at globally, others and still others in between.

This creates a textured approached where no one approach is forced to handle more than it actually has the capability of addressing. Shackelford’s expertise pertains to issues of cybersecurity and “cyber peace” where he argues that multiple governance layers – individual, corporate, local, nation, and international – are necessary to address these technological issues and he suggests that this model may be one that is helpful to considering ideas of music, business and peace.13Shackelford, Should Cybersecurity Be a Human Right?” Exploring the Shared Responsibility” of Cyberpeace.

I have long argued for a similar approach in more explicitly normative terms. Natural law, for example, posits that there are certain human goods that transcend any given society. (What often causes natural law its biggest issues is when a particular culture’s values are assumed to be those universal norms instead of keeping transcendent norms transcendent and recognizing that individual cultures provide meaning and direction to those idiosyncratically.) Recent findings from evolutionary psychology provide support for many of these natural law norms, so much so that some argue that human beings are hardwired to be moral. One may not need to go quite that far – indeed, I do not – and instead arrive at a less controversial, but still important determination that human beings seem to be hardwired to be social creatures, a finding that has been recognized since at least the time of Aristotle.14Fort, Ethics and Governance: Business as Mediating Institution.

One of those more recent anthropological findings is that there are certain limits to the group sizes within which human beings interact. To oversimplify the model, human beings interact intimately in group sizes of four-to-six, on a daily basis in group sizes of up to thirty, and the maximum number of people with whom one can feel that one is in a relationship with amounts to only about one-hundred fifty at any one time.15Ibid. Beyond these numbers, human beings have a difficult time feeling that their actions make a difference to others and beyond these limits it is harder to feel the consequences of one’s actions to others.

The lack of such a phenomenological experience makes it more difficult for people to act ethically – regardless of what the ethics of the community are – exactly because actions do not seem to matter. This empirically grounded research is consistent, again, with traditional natural law that argues that people develop their moral identity through small, “mediating institutions” (such as family, neighborhoods, and voluntary organizations) where people mold their character through interactions with others.16Ibid. Moreover, a multi-tiered model does not have to been traced to naturalism per se; perhaps the leading theory of business ethics today is based on exactly the same model, but derived from Kantian and social contractarian premises.17Donaldson & Dunfee, Ties That Bind: A Social Contracts Theory of Business Ethics.

Thus, like Shackelford’s polycentric governance, my naturalistic model posits both layers of the findings of moral goods as well as dialectical interaction among these levels and these goods. The interactions among members of a mediating institution may be consistent with overarching natural law norms, but they also partake of a thick understanding of what is morally appropriate for that given mediating institution. This is the model I have used to look at the development of ethical corporate culture: there may be overarching global norms to which any culture and any business might ascribe, but there is enormous variability and thick specificity for a given cultures economic instruments and to particular business organizations.

Applicability to Business and to Music

To extrude this model to music, it may be that it is preferable not to search for a single ethic that can differentiate between positive and negative music, but instead to be cognizant of music’s universality and some basic features such as that all possess some form of rhythm and sound (or absences thereof). Then one can further dive into the particulars of the cultural expressions of music. This dialectical process – and importantly viewed as a process – may not produce peace per se, but it may produce harmony. And that harmony may itself eventually yield peace.

To draw upon business as an example, twenty years ago, there was a wide divergence of the view of the acceptability of bribery. Some countries – such as Germany – even allowed bribes to be used as a deduction on income tax returns. Yet, the increasing awareness of the dangers of bribery – including its direct correlation with violence18Fort and Schipani. - led to a widely signed treaty among countries to enact laws to made bribery illegal in their countries.19OECD Convention on Combatting Bribery of Foreign Officials in International Business Transactions. The process of such an awareness and understanding took decades to build. It may take time for people to understand the connection between business and peace and it may take time for people to understand the connection between music, business, and peace.

In a similar way, I differentiate among the different kinds of businesses that contribute to peace. Some social entrepreneurs may set out to achieve a social good through their work and may make peace that social goal. Others may see peace as an instrumental good in that most businesses do better when bombs aren’t falling on their buildings. Still others may be very ethical businesses and have no thought that their conduct might contribute to peace, yet if the argument of many in the business-and-peace is correct – that ethical business contributes to peace – then simply fostering that conduct (apart from peace) may be beneficial. In short, different businesses may contribute to peace in different ways and different musicking may contribute to peace in different ways as well.20Fort, Diplomat in the Corner Office: Corporate Foreign Policy.

As a dialectical, multi-tiered process, the interaction among these different levels may be messy. Moreover, to suggest that different levels of society and different levels of governance may have different responsibilities and also different norms does not fully address the notion of ambivalence. That still lingers. Yet, I would like to suggest that peace itself may be the normative criterion by which we can determine what music – and what businesses – may be most ethically sound. In other words, rather than arguing about which cultural understanding of ethics is correct, could we instead look at anthropological, economic, and other evidence of what seems to produce harmony and use that evidence as the criteria by which we can judge whether some businesses – and whether some music – is leading us ethically.

The argument is, I admit, circular: To aim for peace, we need to adopt those practices that lead toward peace. Circularity is not, however, necessarily a bad thing. There is research on the attributes of relatively peaceful societies.21Fabbro, “Peaceful Societies: An Introduction”; Kelly, Warless Societies and the Origins of War. There are studies of what political processes seem to lead to sustainable “zones of peace."22Kasowics, Zones of Peace in the Third World: South America and West Africa in Comparative Perspective. There are economic analyses of what practices tend to correlate with peace.23Hayek, The Fatal Conceit; Fort, Diplomat in the Corner Office There are metastudies that suggest foundations for peace.24Pinker. There are studies that show what governments tend to be more or less violent.25Weart, Never at War: Why Democracies Will Not Fight One Another. Thus, as a methodological approach –and as an ethical one as well – my suggestion is that there is evidence of how we get to harmony and peace and that this evidence may serve as the heart of the criteria that we can use in order adjudge things that are ethical.

There could be other criteria that one uses to adjudges ethics. One could claim that Aryan rule of the world is the way to determine what is right and wrong. Indeed, such a teleological aim existed and caused catastrophic results. Yet, that is not what we are aiming for. We are aiming for harmony and peace and so why wouldn’t we use those actions that lead to these goals as normative criteria for how to analyze music and business?

Further Extensions

It is worth exploring further how music might help to shape our moral inclinations. The following material describes an exercise I am using with my business ethics students. I do not have enough iterations in order to make any particular claims that might be robust and substantiated, but I do think the exercise is suggestive of the different levels of moral awareness which any given individual inhabits. In short, I ask students to find music that corresponds to different levels of moral development. A central of that exercise is for them to have something “to turn to” when they realize that their ethical orientation may be off-track. Such an exercise is a kind of “nudge.” It is an external push toward thinking in a certain way.

Created individually, this would seem to cause no ethical issues. If an individual recognizes that Palestrina puts her into an ethereal, peaceful spiritual place, then the individual turning to that music at the individual’s choosing creates no loss of moral autonomy. It is a self-generated action (even if recommended by the person’s ethics professor!) created by the person and accessed when the person believes it is necessary to be used.

The harder part concerns when an organization chooses the music and decides when to play it. For example, what if an organization decides to blast sexually explicit and violently pulsing music through the organization’s office. This too might nudge a person’s psychological state and it may do so in a socially problematic way. Then, the person is not in the position to choose; it comes from an external source without the person’s input or assent.

The latter example creates an ethical issue. Creating an ethical issue is not the same thing as concluding that the example is unethical; it simply raises an issue. But the second example does seem to raise serious ethical hurdles whereas the first one does not. One could imagine something in between as well: individuals within an organization having input as to what music they would find motivates them toward the purposes and aims they have at work.

What follows is aimed at the first example rather than the second. Can we use music to nudge individuals to certain stages of ethical development (nudging chosen and controlled by the person) to be used at work/business (or anywhere else for that matter)?

Developmental Models

Over the last half-century years, scholars have created progressive developmental models. Some, like Lawrence Kohlberg and Carol Gilligan provide a model for moral development. Kohlberg said that human beings progress through three stages (he bifurcated each stage as well) of Pre-Conventional (comprised of obedience and/or punishment along with an orientation toward self-interest), Conventional (pertaining to social conformity and law and order orientations, and Post-Conventional (pertaining to social contract and universal ethics orientations). In Pre-conventional morality, one adheres to rules because otherwise, one might get punished. In Conventional morality, one sees the self-interested benefits and rewards of maintaining relationships. In Post-Conventional, one seeks moral truth and practice because of its universal goodliness (and godliness).26Kohlberg, Stages of Moral Development.

Gilligan challenged Kohlberg’s model arguing that his six stages may be true of male-centered morality (all of Kohlberg’s test subjects where men), but not necessarily of women, who might jettison the importance of rules, for example, in order to maintain relationships.27Gilligan, In a Different Voice. This is worth keeping in mind because academic categorizations can simultaneously capture a good deal of truth while also leaving important elements out. Life’s a bit too complex to be able to compartmentalize so neatly.

These studies of moral development have not been left to the psychologists. Theologians and philosophers have done something similar. Covering all of these would range far beyond what I can cover here, but two interesting authors have attempted to create a set of spiritual development stages that are akin to what Kohlberg and Gilligan have done.

James Fowler28All charts on this website are © usefulcharts.com, which provides permission for personal or non-commercial use. and Ken Wilber,29Wilber, Integral Spirituality. for example, use sequential models for spiritual development. Fowler’s studies proposed seven stages of faith development: Undifferentiated; Magical; Mythic-literal; Conventional; Individual-reflexive; Conjunctive, and Universalizing-Commonwealth. As with Kohlberg’s, this model sets out an increasingly developed set of faiths demonstrating a real difference between a view that religion is the same as magic versus a faith that attempts to rationally embrace the entirety of the cosmos.

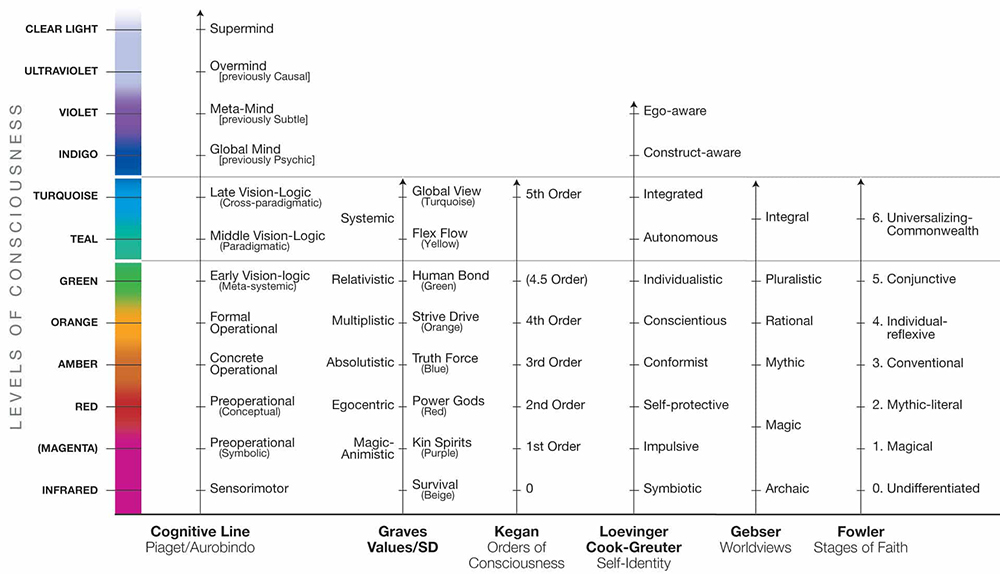

Drawing upon the ancient chakras, which use colors to represent progression spiritual progress, contemporary philosopher Ken Wilber talks about an early stage of spiritual development beginning with magenta, followed by red, yellow, green, and upward through the spectrum of the rainbow. He then places his spiritual development ideas alongside development work of others, such as Fowler, but also such as Jane Loevinger and Susann Cook-Greuterhave,30Gebser, Fowler, Loevinger/Cook-Greuter in Wilber Integral Spirituality. who similarly used color schemes to sketch various aspects of development, as well as well-known theorists such as Jean Piaget, Clare Graves, and Robert Kegan as depicted in the chart below.

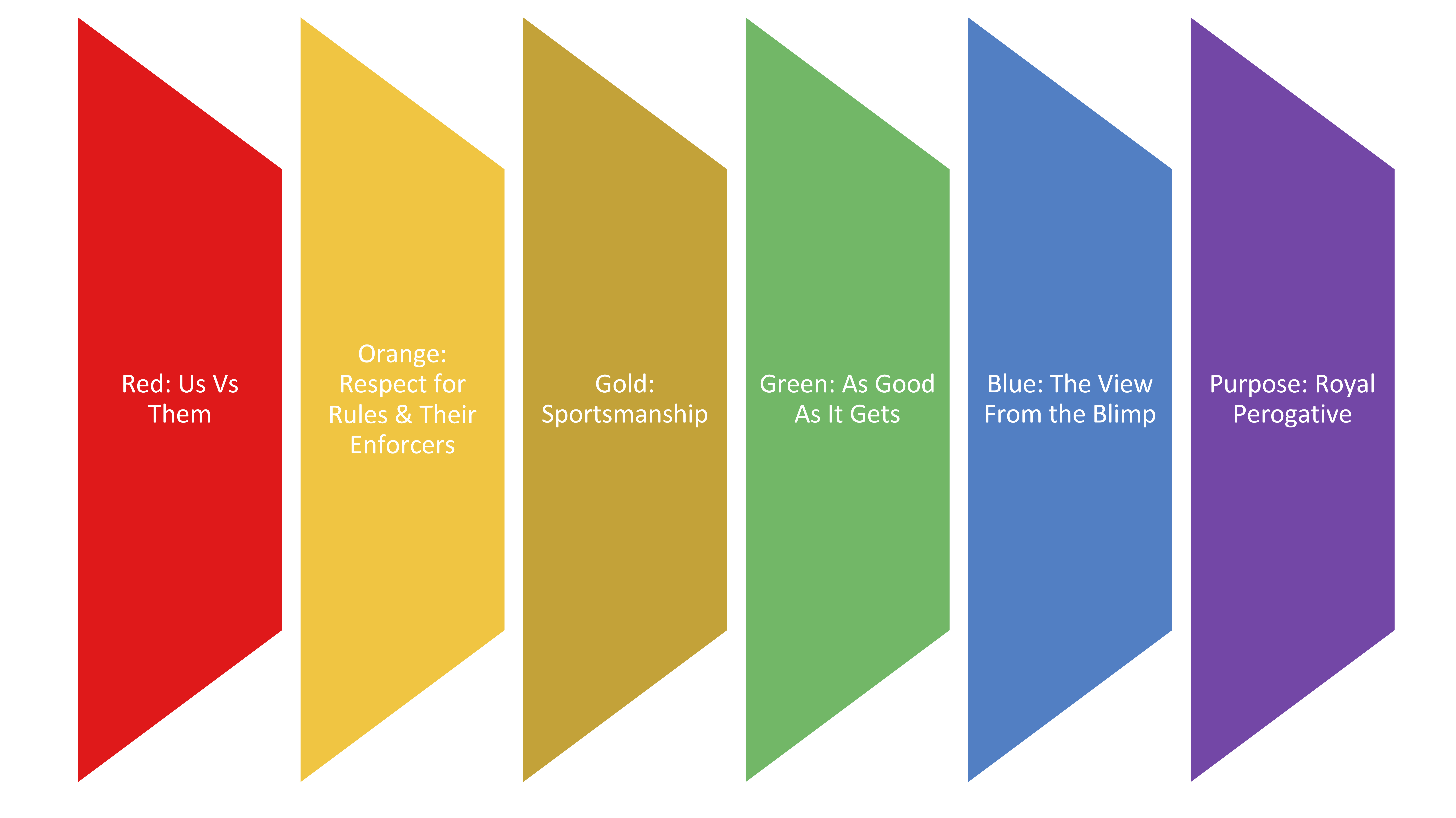

The purpose of setting out these charts isn’t to explain them in full. Indeed, Wilber’s work is the best place to have an explanation of them. However, I want to borrow the idea that Wilber and others borrowed from the chakras. That is, I’d like first to portray the spiritual levels of sports-fandom in a color-coded scheme. Relying on sports may not be necessary for everyone; indeed, I suspect it would not be for readers of College Music Symposium. But it provides an easy entry point for my students and others to understand this sequence of ethical development.

This scheme, I believe, corresponds well to these developmental models just set out. One benefit of doing that to describe how sports can teach us about spirituality is that sports teams come ready-made with jerseys, pants, and sometimes hats to paint the picture. If ever there was a natural fit for the chakras color-coded depictions, it has to be sports. So, let’s think of sports spirituality in the colors of the rainbow, arranged in a non-hierarchical way:

Figure 1, from Ken Wilber, Integral Spirituality (2007)

In red spirituality, sports fans conduct themselves in an “us vs. them” way. You are either for us or against; the purpose of the game is to bend the opponent to our will. In doing so, may the forces of the universe be on our side as we do battle with these scummy opponents. When we do win, “then see, God is on our side.” “Us vs. Them” spirituality, when one finds a greater sense of self by linking one’s identity, voice, passions, and heart with one’s team together with other fans, is a Red spirituality. It’s a perspective that also often correlates with war.

Orange spirituality is about respect for the rules. This means the rules of the game because without rules, one doesn’t even have a game; it’s just a bunch of people running around and perhaps slugging each other. Orange is about respect for the officials and also about respect for those rules that effectuate a fan’s (or player’s) calling on mystical forces of the universe through superstition and, well, wearing the same underwear as long as one’s team continues to win while wearing it.

Gold spirituality is about sportsmanship. It’s about respecting one’s opponent. It’s about sports according to the Golden Rule: Doing unto others as one would have others do to you. This is about seeing the humanity of one’s opponent. That might happen in any game when one empathizes with an opponent’s injury or when an opponent suffers an unfair call. It can also be more profound, such as when the opponent recognizes that the other team is letting a player with a disability get a chance to play and honors that opportunity without subjecting the opponent to the full violence of a football game.

Sports Spirituality as Rainbow of Colors

To provide a more specific example – one that brought a professional football player in my class to tears – consider this collegiate women’s softball game. A player on one team hit the ball over the fence for a home run, but broke her ankle rounding first base. The rules indicated that her teammates could not help her around the bases. The opposing team then asked if there was a rule against them helping the young woman around the bases. The umpire had to admit there was no such rule and so the opposing team did just that, allowing the injured opponent to complete the home run.31Sharon, The Western Oregon Home Run That Won an ESPY.

Gold spirituality – befitting the Golden Rule – treasures not just playing by the rules, it champions a sense of sportsmanship. On the field, that gets exemplified by the players shaking hands even at the end of a hard-fought game. In the stands, it could be a pat on the back of the fellow sitting in front of you who, has alternated with you in primal outbursts of support for your respective teams, but who, in the end, respects each other’s love for his own team as well as gratitude for a game to enjoy.

Green spirituality is “as good as it gets.” It is holistic (akin to green environmentalism that teaches us to think of the entirety of the ecosystem. This is about love of the entirety of the game. This is where a fan sits back and relishes the entire moment that is played out before her. The players, colors, bands, stadium, the crisp autumn day…the whole works. A fan in the Green level of spirituality stops for a moment and takes in the entire event. Not just the score. Not just a fairly played game. Not just the respect of each other, but the entire, fun, sun-splashed (or snow-obscured or rain-drenched) moment that one has been a part of. Green spirituality embraces the love of the game, or maybe even more accurately, the love of the sport.

Blue is the perspective of that big thing that hangs in the sky during a big game: The Blimp. Blue sees the game below, but also notices that the lessons of the game also apply to the other things one can see when in the Blimp. When the television shows the view from the Blimp, a viewer also sees the local neighborhood around the stadium and perhaps the local businesses and the local government and the local religious institutions and much else beside. There is much to learn from watching a game and from the perspective of the Blimp, one can see how those lessons apply to the other institutions one sees. It brings a blue-sky perspective on how this game, this day, this sport connects to a wide range of experiences in life. How sport teaches lessons to kids. How it mirrors our politics. How we can apply what we learn in one place to someplace us.

Purple is royal. The Hindu King, Arjuna, hero of the Bahava-Gita learned that he could engage in battle only by detaching himself from the glories that would result from the battle. Once he had done that, he could participate in battle and not be attached to it. There is, in a sense, a royal movement among various levels and duties. The Bible’s King Solomon set this out in Ecclesiastes: there is a time and season for everything under the sun.32Ecclesiastes 3: 1-8.

Following lessons from Solomon or Arjuna, a person can engage in the blood-curdling cheering of the game-winning field goal and also see how that passionate moment fits in with other spiritualties Each spirituality has its time and season. There are times for Red and times for Green. There are times for Orange and times for Gold. There are times that Purple sees all of the rainbow.

It strikes me as a mistake for us to think that any one of us only occupies any one of Kohlberg’s (or any of the other) development models. We’re not just universalists all the time. We move around. Recognizing that we do move around undercuts the tendency for these models to become elitist because we recognize that each describes a part of our human condition. Sports provide an entry point for seeing how we are just that.

Translation to Music, Ethical Development, and Peace

With this in mind, the assignment I give to students is to understand these various stages of ethical/moral/spiritual development and see how they apply in their lives. This could be in their cheering of sports teams, in international/political developments, or something else. As a way for them to “find” these stages of development, they are to find music that corresponds to these levels. It could be one song (it might be a very long song or, more likely an entire musical or opera) that demonstrates each of these stages. It could be six different songs, each of which captures a stage in question. Or it could be a piece of music that captures two or three (but not all six) stages. The students are to identify the song and then write a brief explanation for why this music demonstrates to them that level.

To be more specific, can they find music that places them in an us vs. them state of mind? It is actually pretty easy to do so. Songs about war – even theatrically such as in Star Wars – provide examples as do military songs, and many school songs. It is also fairly easy for students to also find universal/peaceful songs. The harder ones lay in between these two extremes.

What about rules? Students struggle with this, but actually music (like sports) is music because of some kind of rule that it follows. Music follows rhythms, notes, orchestration, key signatures, and harmonies, each which have some dimension of a musical rule. Students often identify Sportsmanship (Gold) and As Good as it Gets (Green) in songs about friendship and love, sometimes expressed through the music per se and often through the accompanying lyrics. Lyrics also often provide the translation point for The View from the Blimp (Blue).

At this juncture, I have several thousand songs that students have selected to fit into these categories. It would be a good research project to categorize these so that one might be able to determine what of these thousands of songs seem most attuned to the particular levels of development. What I find more important is that students are able to identify for themselves what songs mean to them and in what levels so that they have a resource to claim at those times when they recognize that they need to either reinforce their current moral attitude or when they recognize that they need to move to a different one.

My point is that, within each of us, we may live at different stages of moral development and those levels may be appropriate at a given time and place. Thus, searching for an overarching ethical framework may be difficult, if not impossible, for any given individual, let along for global peace. At the same time, being aware of these levels may provide us a way to express them in ways that are linked to an overarching normative goal of peace. Music, because of its universality, has the potential to help people locate their moral notions and to show them what it feels like to be in another place as well.

Translating to Business

In the Overview of this special issue, a conceptual model is provided as to how business connects to peace and how music connects to business as well. I will not repeat that model here except to say that there is evidence indicating a significant overlap between ethical conduct and peaceful attributes of relatively non-violent societies. There may be some businesses – those which define themselves as social entrepreneurs – that specifically set out to attempt to achieve social as well as economic goals. There are also companies – especially huge multinational ones – that essentially are their own geopolitical entities with an identity apart from any particular nation-state. Then there are, as I have emphasized in all of my writing, companies that may or may not have peace in their mind at all, but which practice ethical behavior, which itself contributes to peace simply because it replicates the behavior of relatively non-violent societies. I believe that this latter category contains the reservoir for the most hope for businesses contributing to peace.

If this is true, then finding the ways in which persons might be nudged to be more ethical also is a nudge toward peace. This does raise issues noted at the beginning of this second part of the article: the autonomy question. That issue does need to be addressed. But even at this more individual level, the notion that there may be tools – related to sports and related to music – that individuals can use in order to orient themselves to be more ethical at work strikes me as an opportunity worth developing further.

Conclusion

My strong sense is that many different cultural forces – music, business, film, sports, law, religion, dance and others – have the potential to shape the interactions among people both on a small and large scale. Olivier Urbain has done a great service in carefully setting out the challenges music faces in making such a contribution. In doing so, he also provides criteria and challenges – and opportunities – that other cultural forces share. His contribution provides a model for us to draw upon in examining the challenges and opportunities in all of these cultural forces.

As I have explained, I also believe that peace itself carries with it a normative orientation and while there is diversity as to what may help peace in one instance and not in another, there are also some themes that suggest how peace has been achieved. If we believe that a sustainable peace – as opposed to a Carthaginian model – is a worthy goal, then our efforts might be best served by understanding such empirical studies and avenues toward peace. There will certainly always be irresolvable debate about what ethical systems are preferable to others, but I suggest that peace itself contains its own normativity that we can utilize to move forward in assessing how all of these cultural forces – music, business, sports, film, law, religion, dance, etc. – can contribute to a better world. That effort will likely entail analysis on multiple levels of human interaction, whether individual, organizational, governmental, or global.

Finally, I have proposed a specific way in which music might serve as a nudge to move business people toward more ethical behavior by providing them touchstones of how a piece of music places them at different levels of moral development. If my argument is correct that ethical businesses contribute to peace, whether they are consciously aware of that contribution or not, then finding tools to boost ethical conduct has benefits for our task of peace. This research is embryonic, but I hope is suggestive.

Notes

1 Urbain, “Business and Music in Peacebuilding Activities: Parallels and Paradoxes” (this issue Symposium 58.3, hereinafter Urbain).

2 With apologies to Bing Crosby. https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=accentuate+the+positive+eliminate+the+negative+lyrics&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8

3 Urbain.

4 Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence and Reconciliation.

5 Pinker, The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined.

6 Fort and Schipani, The Role of Business in Fostering Peaceful Societies.

7 Friedman, India, Pakistan and G.E.

8 Fort and Schipani.

9 Dunfee and Warren.

10 Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening.

11 Urbain.

12 MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality?

13 Shackelford, Should Cybersecurity Be a Human Right?” Exploring the Shared Responsibility” of Cyberpeace.

14 Fort, Ethics and Governance: Business as Mediating Institution.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Donaldson & Dunfee, Ties That Bind: A Social Contracts Theory of Business Ethics.

18 Fort and Schipani.

19 OECD Convention on Combatting Bribery of Foreign Officials in International Business Transactions.

20 Fort, Diplomat in the Corner Office: Corporate Foreign Policy.

21 Fabbro, “Peaceful Societies: An Introduction”; Kelly, Warless Societies and the Origins of War.

22 Kasowics, Zones of Peace in the Third World: South America and West Africa in Comparative Perspective.

23 Hayek, The Fatal Conceit; Fort, Diplomat in the Corner Office

24 Pinker.

25 Weart, Never at War: Why Democracies Will Not Fight One Another.

26 Kohlberg, Stages of Moral Development.

27 Gilligan, In a Different Voice.

28 All charts on this website are © usefulcharts.com, which provides permission for personal or non-commercial use.

29 Wilber, Integral Spirituality.

30 Gebser, Fowler, Loevinger/Cook-Greuter in Wilber Integral Spirituality.

31 Sharon, The Western Oregon Home Run That Won an ESPY.

32 Ecclesiastes 3: 1-8.

Bibliography

Appleby, R. Scott. The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence and Reconciliation. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

David Fabbro. “Peaceful Societies: An Introduction,” Journal of Peace Research 15 (1978): 67-83. doi:10.1177/002234337801500106.

Fort, Timothy L. and Cindy A. Schipani. The Role of Business in Fostering Peaceful Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Friedman, Thomas L. “India, Pakistan, & G.E.,” New York Times (August 11, 1998).

Hayek, F.A. The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. Whose Justice? Which Rationality? South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1988.

Pinker, Steven. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. New York: Viking Books, 2011.

Small, Christopher. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press/University Press of New England, 1998.

Weart, Spencer R. Never at War: Why Democracies Will Not Fight One Another. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Wilber, Ken. Integral Spirituality: A Startling New Role for Religion in the Modern and Postmodern World. Internet resource, 2007.