Abstract

Educators are no longer the keepers of content. With the increase in accessibility to technology and the internet, teachers need to show students how to think critically and use facts to influence their own independence and creativity in the learning process. This paper outlines the history of concept-based pedagogy as well as its successful application in other interaction-based fields. It then demonstrates the application of concept-based pedagogy to a selected clarinet work. Using principles of concept-based pedagogy, the work is broken down to its component technical and expressive parts in order to address larger musical concepts. One exercise each in the areas of tone, technique, rhythm, and phrasing address challenges presented in the work. The goal is to demonstrate the successful application of an alternative pedagogy to the long-standing master-apprentice system of education established in the private studio.

Donald Henriques

Introduction

Educators are no longer the stewards of content. If students can access most facts and information via the internet, what then becomes the role of the educator? With concept-based pedagogy, instructors are not merely teaching students how to play a composition with appropriate style and specific inflection, but also how to apply long tones, scales, technique building passages, articulation studies, and etudes to repertoire. The areas students receive instruction in are not repertoire-specific but rather connected intimately to the fundamental areas of music performance including tone, technique, rhythm, and phrasing. Though many teachers strive to teach this way (and when asked would say they do), what is found is that we can, as educators, get wrapped up in the smaller minutiae that connect into a larger picture that we understand, but do not always make clear to our students. Though this idea has long been a pillar of educational theory and philosophy, it is not uniformly applied to individual instrument instruction. It has, however, been applied to large ensemble pedagogy via the Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance movement and has seen significant application to large ensemble pedagogy.

A significant amount of concept-based pedagogy scholarship exists in fields other than music. The exception to this trend is Therese Ditto’s (2014) dissertation entitled, “Content-Based Curriculum versus Concept-Based Curriculum: A Retrospective Causal Comparative Study to Identify Impact on the Development of Critical Thinking” that directly compares the effectiveness of content-based pedagogy to concept-based pedagogy, outlining in detail its effectiveness as a teaching and learning tool.1Therese J. Ditto, “Content-Based Curriculum Versus Concept-Based Curriculum: A Retrospective Causal Comparative Study to Identify Impact on the Development of Critical Thinking” (EdD diss., Capella University, 2014). In this dissertation the author describes in detail the application of concept-based pedagogy versus that of content-based pedagogy specific to music, and is the only study of its kind to do so. The conclusion here is that concept-based pedagogy is more likely to remain with the student because it addresses larger areas of learning that are transferable between pieces of repertoire. Its successful application is widely documented in the areas of nursing and language learning, both human-interaction based fields.

A significant amount of the research on concept-based pedagogy exists in the field of nursing. Nelson-Brantley and Laverentz (2014)2Heather V. Nelson-Brantley and Delois M. Laverentz, “Leaderless Organization: Active Learning Strategy in a Concept-Based Curriculum,” Journal of Nursing Education 53, no. 8 (August 2013): 484 – 501. , Edwards (2015)3Patricia Allen Edwards, “The Effects of a Concept-Based Curriculum on Nursing Students' NCLEX-RN Exam Scores,” (EdD diss., Walden University, 2015). , and Buchanon (2016)4Monica R. Buchanon, “A qualitative study exploring faculty experiences with concept-based curriculum and NCLEX-RN preparation” (EdD., Capella University, 2016). outline learning, teaching, and assessment in a concept-based curriculum. Laverentz (2014) writes that: “Concept-based teaching as a pedagogy focuses student learning on a core set of concepts relevant to nursing, such as perfusion, pain, coping, or glucose regulation. By gaining a deep understanding of key concepts, students are able to recognize recurring characteristics and apply them to a wide variety of clinical situations.”5Heather V. Nelson-Brantley and Delois M. Laverentz, “Leaderless Organization: Active Learning Strategy in a Concept-Based Curriculum,” Journal of Nursing Education 53, no. 8 (August 2013): 484 – 501. Though the concepts differ from concepts in music, the general logic remains the same and emphasizes the transferability of conceptual learning. Additional studies including Higgins (2017)6Bonnie Higgins and Helen Reid “Enhancing ‘Conceptual Teaching and Learning’ in a Concept-Based Curriculum.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing 12, no. 3 (April 2017): 95-102. and Nelson-Brantley (2013)7Heather V. Nelson-Brantley and Delois M. Laverentz, “Leaderless Organization: Active Learning Strategy in a Concept-Based Curriculum,” Journal of Nursing Education 53, no. 8 (August 2013): 484 – 501. elaborate on other benefits of the system in the scope of a curriculum. Higgins (2017) writes that, “the concept analysis diagrams (CADs) encourage analysis through correlation of concepts and interrelatedness of patients, fostering the use of ‘conceptual thinking’ rather than rote memorization or focusing on the medical model.”8Bonnie Higgins and Helen Reid “Enhancing ‘Conceptual Teaching and Learning’ in a Concept-Based Curriculum.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing 12, no. 3 (April 2017): 95-102. Again, although the terminology is that of nursing and health sciences, the application to private teaching is nonetheless apparent in the breaking down of a larger task or skill into smaller, more manageable pieces directly connected to the concept.

Application of Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance to the Applied Studio

Why has neither concept-based pedagogy nor Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance emerged as a successful private teaching methodology? The answer may lie in the roots of the private instrumental instruction, often based on a master-apprentice system that teaches one piece or style of music within its own context. Though teachers may have detailed information on standard or often-played repertoire, it is not practical to attempt to teach repertoire in isolation. Concept-based pedagogy requires students to make connections between pieces of different style and period. In order to merge both concept-based pedagogy with ideas from Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance, it is important to examine the works of Sindberg and Erickson.

In 2007, Lynn Erickson began writing extensively about the application of concept-based instruction. She utilizes many of the same principles as Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance but applies these principles in the elementary classroom rather than a large band setting. Her three publications, Stirring the Head, Heart, and Soul: Redefining Curriculum and Instruction (2007)9H. Lynn Erickson, Stirring the Head, Heart, and Soul: Redefining Curriculum, Instruction, and Concept-Based Learning (Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2007). , Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom (2006)10H. Lynn Erickson, Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction: Teaching Beyond the Facts (Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2002). , and Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction: Teaching Beyond the Facts (2002),11Ibid. explore the concept of integrated thinking, seeing the patterns and connections of knowledge at a conceptual and transferable level of understanding. While Erickson works with the most general application of concept-based pedagogy, Sindberg’s connection to music makes her studies even more pertinent to the research at hand.

Sindberg’s studies incorporate many aspects of Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance including its application to music teaching and its effects on learning. In a 2006 study, she explored the lived experiences of Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance students in detail through interviews as well as quantitative research.12Laura K. Sindberg, “Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance (CMP) in the Lived Experience of Students” (Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 2006). Her 2016 study examined aspects of successful implementation of Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance from a teaching standpoint.13Laura K. Sindberg, “Elements of a Successful Professional Learning Community for Music Teachers Using Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance,” Journal of Research in Music Education, 64(2): 202-219, 2016. An outline of Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance is given in her 2009 study.14Laura K. Sindberg, “Intentions and Perceptions: In Search of Alignment,” Music Educators Journal, 95(4) 18-22, 2009. All of her works, much like the other works of scholarship on concept-based pedagogy or Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance, emphasize the transferability of information and critical thinking that results from learning in a concept-based, rather than content-based, way.

The idea of using concept-based pedagogy in teaching to achieve deeper understanding is nothing new or revolutionary. However, bringing the conceptual nature of instruction to the attention of students, explaining how to transfer large concepts learned in one piece to new contexts in other areas, and making that the basis for instruction in the private lesson setting has yet to be explored to its fullest extent.

Conventionally, many teachers believe that the purpose of teaching is to transfer factual knowledge that will eventually lead to independent understanding. Concept-based pedagogy is the notion that students will, “know factually, understand conceptually, and do skillfully. Traditionally, curriculum and instruction has been more two-dimensional in design (know and able to do)—resting on a misguided assumption that knowing facts is evidence of deeper, conceptual understanding.”15H. Lynn Erickson, Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom (Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2006), 5.

In an applied studio context, “factual knowledge” comprises successful strategies clarinet students learn in order to practice and produce an effective performance of a specific piece, and how these strategies connect back to fundamental pillars of playing the clarinet correctly in the mechanical sense so that students can master the physical playing of the instrument in order to be able to focus more and more on the underlying emotional interpretation of the music. In a typical master-apprentice system, many especially younger students, move from work to work, carrying only small pieces of larger concepts that they learn from piece to piece, essentially creating an entirely new context for each subsequent piece. In a repertoire-based teaching setting, students apply knowledge gained from specific piece without necessarily being taught how to apply such knowledge to subsequent works studied. Concept-based pedagogy aims to prevent this limited approach.

With concept-based pedagogy as its backbone, the following example explores specific areas of fundamental musicianship as defined by the Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance program via Viet Cuong’s work for unaccompanied clarinet, Zanelle (2009). By studying this piece through larger concepts, students will acquire transferable knowledge applicable in many different contexts, rather than learning a piece solely within its own context as evidenced by their use with students in a studio context. In Shaping Sound Musicians: An Innovative Approach to Teaching Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance, Patricia O’Toole, a founding Wisconsin Music Educator of CMP, addresses the specific concepts of tone production, rhythmic subdivision, technical execution, and musical phrasing, that will be used as the basis for examination here. For the purposes of this document, tone production, technique, rhythm, and expression will be used. Using these conceptual areas, the challenges of this work will be defined and solutions proposed.

Pertinent background information about the composer introduces the work. One challenge in each of the pedagogical areas of tone, technique, rhythm, and phrasing is addressed with a corresponding conceptual exercise. The exercises offered are in no way intended to be the only solution to the proposed challenges, but are provided only as an example of one possible resolution. Each exercise has been written to be adapted to suit similar problems in any piece of repertoire by changing the pitches, rhythms, time signature, or any other element in order to make it as pertinent as possible for the problem at hand.

Performance suggestions are provided to emphasize the transferability of the information in each exercise, which is intended to be delivered by a skilled professional teacher. The following is not intended for use by students alone but rather for teachers to begin to examine their own pedagogy and its overall effectiveness. Older students could benefit from the following explanations, but will still require clarification. For that reason, metronome markings are suggested, but, like all other elements of the exercise, can and should be adapted to suit the individual needs of the student and repertoire.

Finally, assessment of the effectiveness of the conceptual exercises presented will be different for each student and each challenge in each unique repertoire situation. It should be noted that each student will respond differently to each concept and exercise. It is up to the teacher to organize her thoughts and pedagogy such that she can present key concepts to the student in the way that the individual student will understand most effectively for long term transferability of information. Because each student is different, each outcome will be different. Success for one student who may have particular trouble with a concept, would not be defined as success for a student who doesn’t experience the same difficulties in that area.

Zanelle (2009), Viet Cuong (b. 1990)

Composer Background

Viet Cuong (b. 1990) was raised in Marietta, Georgia. His works have been performed on six continents. He currently holds the Daniel W. Dietrich II Composition Fellowship at the Curtis Institute for Music. Prior to this, he received an M.F.A. from Princeton University as a Naumburg and Roger Sessions Fellow and studied with such notable composers as Steve Mackey, Donnacha Dennehy, Dan Trueman, Dmitri Tymoczko, Paul Lansky, and Louis Andriessen. Cuong has held residencies at the Yaddo Artist Retreat, Copland House, and Atlantic Center for the Arts in addition to numerous other awards and honors.16“Biography,” Viet Cuong Website, last modified June, 2017, accessed November 28, 2017, http://vietcuongmusic.com/about.

Cuong’s compositional style is characterized by its rhythmic intensity and use of the additive variation technique by which he slowly transforms the melodic ostinati that comprise much of his primary compositional material. His work, Zanelle (2009) is a programmatic work for which Cuong wrote the following:

“A Zanelle is a piece of artwork painted by a robot or machinery. Unlike other forms of machine-made artwork, a Zanelle is created with actual brushstrokes and paint. It is fascinating to watch a machine alternate quickly between sharp, jolting gestures and fluid brush strokes. Even though it occasionally pauses to reapply paint to its brush, the machine maintains a sense of rhythmic propulsion and effortless pacing. My piece Zanelle therefore not only reflects a finished piece of artwork: it also narrates the process in which the art was created.”17Viet Cuong, Zanelle (New York City: Viet Cuong Music, 2009).

Zanelle poses advanced technical, range, and expressive challenges for a clarinetist to surmount in order to perform the work convincingly. Development of consistent tone production at the extreme fortissimo and pianissimo dynamic levels is paramount. Extended technical and expressive passagework with difficult articulation and voicing demands throughout all registers requires advanced strategies for technical practice and analysis. Major rhythmic challenges center on constant meter change from duple subdivision, to triple subdivision, to mixed meter, and back again.

Tone: Consistent Voicing Over Large Leaps

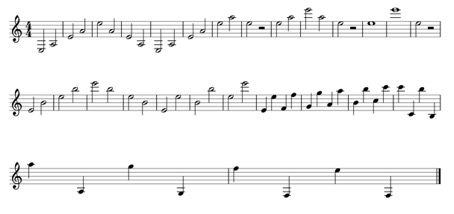

At the advanced college level, it may be assumed that a student can comfortably and consistently produce a balanced tone full of color and overtones throughout the range of the instrument. However, it is likely that playing large two octave leaps at Zanelle’s marked tempo of quarter note equals 160 will pose a challenge to any player. Additionally, students may not have ample experience exploring the outer limits of their dynamic palette. Zanelle provides not only an opportunity to work through all of these challenges but requires that a clarinetist execute a staccato articulation on all notes at extreme dynamic levels (see Figure 1 below) and fast tempi.

FIGURE 1: Cuong’s Zanelle m. 27-36

As observed above, measures 27-36 require execution of staccato, articulated two-octave leaps at piano and forte dynamic levels, in a mixed-meter time signature, at the marked tempo of quarter note equals 160. Though a student approaching this work will have presumably practiced large leaps already in other works as well as in technical etudes and scale practice, a student may not have encountered articulated large leaps in a fast tempo with deliberate and exaggerated dynamic considerations. Though much repertoire requires some combination of these characteristics, few require all of them simultaneously. In order for all of these foundational aspects of clarinet playing to be executed successfully, consistently, and simultaneously, a student must understand how to consistently engage the support mechanism at all times to produce a beautiful, full tone free from adverse embouchure engagement such as excessive lower jaw pressure or pinching. This can be achieved through mastery of different types of exercises including third octave scales at the piano, pianissmo, mezzo forte, forte, and fortissimo dynamic levels concentrating on smooth connection between notes created by the flowing air.

Addressing voicing before the other skill requirements in Zanelle ensures that air support is in place while also training the student to perceive optimal tongue placement for extreme skips. Exercise 1 below is designed to address large leap voicing control.

EXERCISE 1: Exercise for the voicing of large leaps

Students could apply this exercise to any passage in any piece featuring large leaps at a fast tempo. A metronome should be used to gradually increase tempo, beginning at half of the desired tempo and continuing to the notated tempo. As mentioned previously, keeping detailed and accurate record of each tempo increase is paramount to reaching the goal tempo. Students should be careful not to rush this process, taking care to perform consistently at one tempo before moving to a faster tempo. Once a desired tempo has been reached, a student should add the additional layer of practicing at various dynamic levels while maintaining appropriate voicing and air support. The equally difficult articulation challenge is addressed in the following section. It is worth mentioning that, as works increase in difficulty, they often incorporate many different challenges into one passage, making it even more important for a student to be able to identify the various challenges and separate them if necessary to achieve mastery.

Technique: Developing a Healthy Staccato in Large Leaps

A student approaching this work would likely already know many traditional methods for evaluating and practicing technique. Additionally, a student would likely have a strong grasp of basic technical rudiments, including scale and arpeggios patterns in all major and minor keys. It is the simultaneous combination of skills required to perform this work that make it challenging. Large leaps and voicing having been previously addressed; the most pressing technical issue here is the acquisition of crisp staccato.

Staccato is one element of clarinet performance already explored by a wealth of resources. What lacks in these resources, however, are exercises designed to improve ease of production of staccato in all registers and over large leaps with accompanying explanation. Before moving into Zanelle, it is useful to review the process of achieving a crisp and unforced staccato articulation.

As with any articulation on the clarinet, the root of healthy staccato is in efficient air support. Without sufficient air support, the air pressure required to produce the characteristic spark of the articulation is not possible without using other unhealthy means such as excessive upward jaw pressure. Articulation is produced by gentle, momentary interruption of the vibrations of the reed by the tongue. What delineates staccato articulation from one’s default articulation or legato articulation is the amount of time the tongue spends on the reed. To describe this in terms of actual time would be almost impossible; it makes more sense to describe it in terms of the type of articulation syllables used to produce it.

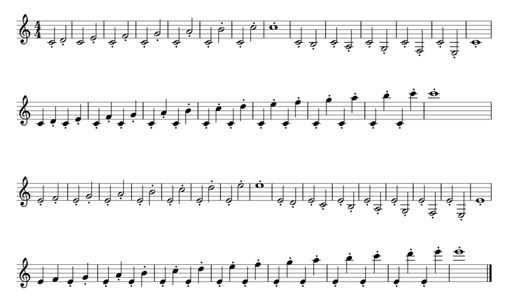

To effectively and consistently produce staccato articulation, a clarinetist must choose articulation syllables that produce the desired tongue motion, sound, and style. In woodwind pedagogy we often consider only the beginning of the note. However, in creating an effective staccato, we must also consider what the tongue does at the end of the note. The “TEE” articulation is often used to create a default articulation that has an open ending, allowing vibrations of the reed to sound until the next interruption by the tongue. Conversely, the “TEET” adds an additional ‘t’ at the end of the articulation syllable, allowing a clarinetist to hear the end of the articulation as well as the beginning. Hearing the ending of the “TEET” indicates that the amount of time the tongue is on the reed is significantly longer than with the open “TEE.” The increased non-vibration time of the reed creates the characteristic separation of the staccato articulation required in Zanelle as shown in Figure 2 below.

FIGURE 2: Cuong’s, Zanelle m. 28-36.

As stated earlier, the combination of the staccato articulation challenge with the large leaps posed here is demanding for a clarinetist of any level to achieve successfully. Experienced woodwind players have a variety of devices that they may use to achieve success in a passage such as this, but when utilizing Zanelle as a teaching tool, it is important for undergraduates to learn to navigate such challenges in this work, as well as others like it they may encounter. The large leaps and common resulting voicing issues are addressed in the first section of this chapter. Exercise 2 below is designed to address the added articulation challenge.

EXERCISE 2: For the development of ease in staccato articulated large leaps

Students should practice this exercise in a variety of different tempos ranging from as low as 50 bpm to at least 144 using the “TEET” syllable. More advanced students might strive to work the tempo up to 160 or 180. Though written in half notes and quarter notes, the exercise should be practiced until it can be read with one large beat per bar, making the quarter notes feel as fast as sixteenth-notes. Students should be careful not to increase the tempo of this exercise too quickly because the goal is speed over time only after voicing has been perfected. Students may then begin to play this exercise in different keys and with chromatic steps rather than major or minor patterns. The goal is not perfection of voicing, though it also should be consistent, but instead the acquisition a healthy staccato over a large leap. Students should be aware of maintaining a high and forward tongue position, avoiding excessive tension in the throat and chest. Consistent support from the core should provide the foundation for this exercise. Additionally, the movement of the gentle movement of the tongue should not impede voicing; only the front of the tongue moves in articulation. If the tongue is moving enough to affect voicing, then the student should practice the exercise first without the staccato, in a slurred manner to be sure voicing is optimal for the range being played.

Rhythm and Phrasing: Developing a Process to Learn, Practice, and Make Musical Decisions

At the late undergraduate level of development, a student will likely be able to precisely decipher rhythmic figures. To reiterate, a major challenge of Zanelle is the change in time signature that occurs regularly and at a very fast tempo, combined with staccato articulation and large leaps.

In order to practice the challenging rhythmic aspects of this piece, two specific techniques are recommended. The first is to create a rhythmic practice sheet containing the least familiar rhythmic figures from the piece collected in one place. A student should make several copies of this sheet and practice writing in the rhythmic “syllables”. Next, a student should practice chanting these rhythms daily with a metronome starting at 50 moving to 144 set to the eighth-note, as well as performing them on a singular note on the clarinet in order to increase effectiveness with the same tempi. Finally, the student should make at least three additional copies of the entire piece on which to write the rhythm syllables to practice chanting and performing on one note.

After rhythmic challenges have been examined, and a practice plan to remedy any rhythmic deficiencies has been made, a student should undertake an analysis of the work’s form. Students should first look for the largest sections of the work by identifying similar materials likely present in a sonata form or a repeated theme as in a rondo form. Then the phrases of each large section should be defined, identifying the climax of each section. After defining the form, a student could practice the following sequence, outlined in Exercise 3. below, on a daily basis.

EXERCISE 3: Step by step process for breaking down difficult passages of music

- Choose a passage of music no longer than eight measures.

- Set a metronome to half the marked tempo, and chant only the rhythm with preferred rhythmic syllables. Ideally, repeat five times without directly reading the rhythmic syllables. If the passage is particularly troublesome, it may be helpful to add a step simply reading the syllables for familiarity before chanting them without reading the syllables.

- Play the chanted rhythm on one note five times while thinking the rhythm syllables.

- Chant the names of the notes in rhythm five times. For flats add the suffix “-eef” to the end of the note, and for sharps, add the suffix “-ese.”

- Chant the names of the notes in rhythm while fingering the notes five times.

- At half tempo, play the passage five times accurately and precisely. If a mistake is made, stop and reduce the tempo by five.

- If there is a fingering-based problem, go back to Step 3 and repeat, adding a step wherein pitches only are played without the written rhythm. Pitches should be played in order as half notes, then quarter notes, then eighth notes and then triplets to isolate any technical or finger motion based challenges.

- Once the selected passage can be performed reliably, add the articulations to the passage, and practice the passage five times in a row perfectly for consistency. If there are many different kinds of articulations that are confusing, a student may begin by slurring the entire passage, adding in one articulation at a time until all are added. The passage should be repeated five times again.

- Add in the dynamic and shaping elements of the work. Based on the preparative analysis done before playing or practicing the work, a student should understand the overall form, the large sections of the work, and the phrases of each section. Using that information, a student should use another copy of the music to mark the high points of each large section, deciding where the ultimate climax of the work is, and creating phrase markings appropriate for the desired shape. Finally, a student will tie everything together by playing the passage through five times with all correct rhythms, pitches, articulations, phrasing, and form considerations.

- Finally, increase the tempo incrementally. This is done by playing the passage through five times correctly, increasing the tempo by ten clicks, playing the passage once, decreasing the tempo by five, and playing the passage again five times correctly. This process is repeated until the desired tempo is achieved.

- Repeat this process for all passages that contain unfamiliar rhythms or time signatures and for meticulous preparation of any work of any level.

Because of the sequential nature of this exercise, it will be most effective for an undergraduate student to work through a passage of moderate difficulty under the direction of the teacher first before continuing to learn the rest of the work independently. Because the level of a student who is most likely to perform this is more advanced, it is conceivable that a student might learn the work completely, playing passagework too fast and without rhythmic accuracy. It is essential to emphasize the importance of taking the step-by-step process seriously. Not only will the process encourage students to be honest about their abilities to play consistently and accurately, but repetition will also feed a student’s ability to focus, teaching them to practice more efficiently and to set clear practice goals for each session. With such a process familiar and established, a student can move into meticulously planned performance preparation. Students now have tools that prepare them for a career requiring advanced time management skills.

Conclusion

Skipping over concept-based instruction produces musicians who are often not equipped to interpret and create. If students are merely mimicking what someone told them to do, they are likely not having as profound an experience as if they had produced the interpretation on their own, with guidance from a mentor. As a result, they cannot interpret music without a guide and cannot communicate effectively with an audience. If a performer isn’t connecting with the audience, and is merely reproducing a recording, there is no reason to attend a live performance. Without an audience, music performance as we know it will no longer exist.

Using Concept-Based Pedagogy in the clarinet studio, or other applied instrumental or vocal areas, allows students to experience the process of learning, practicing, honing, and ultimately performing music in a more personal way. Ideally learning in this way leads to internalization of the overall concepts, rather than specific parts of content that, as we know in music, regularly changes. The examples provided for Cuong’s work, Zanelle, clearly demonstrate the application of concept-based pedagogy in regards to learning specifically unaccompanied repertoire.

In order for our art to survive, we must strive to produce musicians who are capable of informed musical thought rather than creating students who are dependent on teachers to tell them how a piece should be performed. We need to provide students with tools to decipher music for themselves via guided instruction in transferable concepts. In an increasingly information-based society, teachers must be able to provide students with something other than factual information or music education will also die because musical education is so much more than simply factual information.

Notes

1 Therese J. Ditto, “Content-Based Curriculum Versus Concept-Based Curriculum: A Retrospective Causal Comparative Study to Identify Impact on the Development of Critical Thinking” (EdD diss., Capella University, 2014).

2 Heather V. Nelson-Brantley and Delois M. Laverentz, “Leaderless Organization: Active Learning Strategy in a Concept-Based Curriculum,” Journal of Nursing Education 53, no. 8 (August 2013): 484 – 501.

3 Patricia Allen Edwards, “The Effects of a Concept-Based Curriculum on Nursing Students' NCLEX-RN Exam Scores,” (EdD diss., Walden University, 2015).

4 Monica R. Buchanon, “A qualitative study exploring faculty experiences with concept-based curriculum and NCLEX-RN preparation” (EdD., Capella University, 2016).

5 Heather V. Nelson-Brantley and Delois M. Laverentz, “Leaderless Organization: Active Learning Strategy in a Concept-Based Curriculum,” Journal of Nursing Education 53, no. 8 (August 2013): 484 – 501.

6 Bonnie Higgins and Helen Reid “Enhancing ‘Conceptual Teaching and Learning’ in a Concept-Based Curriculum.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing 12, no. 3 (April 2017): 95-102.

7 Heather V. Nelson-Brantley and Delois M. Laverentz, “Leaderless Organization: Active Learning Strategy in a Concept-Based Curriculum,” Journal of Nursing Education 53, no. 8 (August 2013): 484 – 501.

8 Bonnie Higgins and Helen Reid “Enhancing ‘Conceptual Teaching and Learning’ in a Concept-Based Curriculum.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing 12, no. 3 (April 2017): 95-102.

9 H. Lynn Erickson, Stirring the Head, Heart, and Soul: Redefining Curriculum, Instruction, and Concept-Based Learning (Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2007).

10 H. Lynn Erickson, Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction: Teaching Beyond the Facts (Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2002).

11 Ibid.

12 Laura K. Sindberg, “Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance (CMP) in the Lived Experience of Students” (Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 2006).

13 Laura K. Sindberg, “Elements of a Successful Professional Learning Community for Music Teachers Using Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance,” Journal of Research in Music Education, 64(2): 202-219, 2016.

14 Laura K. Sindberg, “Intentions and Perceptions: In Search of Alignment,” Music Educators Journal, 95(4) 18-22, 2009.

15 H. Lynn Erickson, Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom (Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2006), 5.

16 “Biography,” Viet Cuong Website, last modified June, 2017, accessed November 28, 2017, http://vietcuongmusic.com/about.

17 Viet Cuong, Zanelle (New York City: Viet Cuong Music, 2009).

Bibliography

Articles

Beglarian, Grant. “Music, Education, and the University.” Music Educator’s Journal 54, no. 1 (1967): 42-118.

Berg, Margaret H., Sindberg, Laura K. “Supports for and Constraints on Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance-Based Student Teaching.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 201, (Summer 2014), 61-77.

Boyle, David J. “Teaching Comprehensive Musicianship at the College Level.” Journal of Research in Music Education, 19(3): 326-336, 1971.

Carucci, Christine A. “Just Good Teaching: Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance in Theory and Practice.” Music Educators Journal, 100(2), 18, 2013.

Ester, Don P., Scheib, John W., and Inks, Kimberly J."Takadimi: A Rhythm System for All Ages." Music Educators Journal 93, (November 2006): 60–65.

Falthin, Peter. “Synthetic Activity: Semiosis, Conceptualizations and Meaning-Making in Music Composition.” Journal of Music, Technology & Education 7, no. 2. (October 2014) 141-161.

Fehrmann, Ingo. “Teaching the form-function mapping of German ‘prefield’ elements using Concept-Based Instruction.” Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association 4, no. 1 (January 2016): 153.

Friedrichsen, Debra and Smith, Christina.“Propagation from the Start: The Spread of a Concept-Based Instructional Tool.” Educational Technology Research and Development 65, no. 1 (2017): 177 – 202.

Golledge, Reginald, Marsh, Meredith, and Sarah Battersby. “A Conceptual Framework for Facilitating Geospatial Thinking.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98, no. 2 (June, 2008), 285-308.

Gregory, Amy E. and Patricia Lunn. “A Concept-based Approach to the Subjunctive.” Hispania 95, no. 2 (June 2012), 333-343.

Grashel, John. “An Integrated Approach: Comprehensive Musicianship.” Music Educators Journal, 79(8), 1993.

Hiatt, James S. and Cross, Sam. “Teaching and Using Audiation in Classroom Instruction and Applied Lessons with Advanced Students.” Music Educators Journal 92, no. 5 (May 2006): 46-49.

Kohl, Jerome. “Harmonies and the Path from Beauty to Awakening: Hours 5 – 12 of Stockhausen’s Klang.” Perspectives of New Music 50 (2012): 476-523.

Merriman, Lyle. “Unaccompanied Woodwind Solos.” Journal of Research in Music Education 14 (1966): 33-40.

Nelson-Brantley, Heather V. and Laverentz, Delois M. “Leaderless Organization: Active Learning Strategy in a Concept-Based Curriculum.” Journal of Nursing Education 53, no. 8 (August 2014): 484 – 501.

Roe, David W. “Shaping Sound Musicians: An Innovative Approach to Teaching Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance.” Music Educators Journal, 91(1), 2004.

Sindberg, Laura K. “Elements of a Successful Professional Learning Community for Music Teachers Using Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance.” Journal of Research in Music Education, 64(2): 202-219, 2016.

———. “Intentions and Perceptions: In Search of Alignment.” Music Educators Journal, 95(4) 18-22, 2009.

Van Compernolle, Rémi A. “Developing Second Language Sociopragmatic Knowledge Through Concept-Based Instruction: A Microgenetic Case Study.” Journal of Pragmatics 43, no. 13. (2011): 3267 – 3283.

White, Benjamin J. “A Conceptual Approach to the Instruction of Phrasal Verbs.” The Modern Language Journal 96, no. 3 (Fall 2012), 419- 438.

Wolkowicz, Terry. “Concept-Based Arts Integration: Lessons Learned from an Application in Music and Biology.” Music Educators Journal 7, no. 103 (June 2017) 40-47.

Woods, David G. “Comprehensive Musicianship.” Independent School Bulletin 32(1): 61-63, 1972.

Books

Berlioz, Hector and Richard Strauss trans. Theodore Front. Treatise on Instrumentation. Mineola, NY: Dover Publishing, 1991.

Burkholder, Peter J. and Grout, Donald J. “Polonaise.” A History of Western Music, 9th ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2014.

Edwards, Lee and Edwards, Elizabeth Spalding. A Brief History of the Cold War. Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, 2016.

Erickson, H. Lynn and Lanning, Lois A. Transitioning to Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction: How to Bring Content and Process Together. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2013.

Erickson, H. Lynn. Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2006.

———. Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction: Teaching Beyond the Facts. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2002.

———. Stirring the Head, Heart, and Soul: Redefining Curriculum, Instruction, and Concept-Based Learning. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Publishing, 2007.

Gillespie, James E. Jr. Solos for Unaccompanied Clarinet: An Annotated Bibliography of Published Works. Detroit Studies in Music Bibliography, Vol. 28. Detroit: Information Coordinators, 1973.

Guy, Larry. Articulation Development for Clarinetists: Including Exercises and Passages from the Orchestral and Chamber Music Repertoire. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press, 2016.

———. Complete Daniel Bonade – Clarinet Method. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press, 2001.

———. Embouchure Building for Clarinetists. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press, 2001.

———. Hand and Finger Development for Clarinetists. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press, 2007.

———. Intonation Training for Clarinetists. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press, 1996.

———. Selection, Adjustment, and Care of Single Reeds: A Handbook for Clarinetists and Saxophonists. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press, 1997.

Heim, Norman. Clarinet Literature in Outline. Greater Sudbury, ON: Norcat Publishing, 1984; 2006.

Mark, Michael L. A Concise History of American Music Education. Lanham, MD: R an L Education, 2008.

O’Toole, Patricia. Shaping Sound Musicians: An Innovative Approach to Teaching Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance. Chicago: GIA Publications, 2003.

Rimsky-Korsakov, Nicolai trans. Maxamillian Steinberg. Principles of Orchestration. New York City: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

Sindberg, Laura. Just Good Teaching: Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance in Theory and Practice. Philadelphia: R&L Education, 2012.

Thurmond, James Morgan. Note Grouping: A Method for Achieving Expression and Style in Musical Performance. Delray Beach, FL: Meredith Music, 1982.

Dissertations and Theses

Anderson, John E. “An Analytical and Interpretive Study and Performance of Three Twentieth-Century Works for Unaccompanied Clarinet.” D.M.A. diss., Columbia University, 1974.

Behm, Gary W. “A Comprehensive Performance Project in Clarinet Literature with an Essay on the Use of Extended, or New, Techniques in Selected Unaccompanied Clarinet Solos Published from 1960 through 1987.” D.M.A. diss., University of Southern Mississippi, 1992.

Black, Lonnie Gene. “Development of a Model for Implementing a Program of Comprehensive Musicianship at the Collegiate Level.” Ph.D. diss., The University of Alabama, 1972.

Buchanon, Monica R. “A qualitative study exploring faculty experiences with concept-based curriculum and NCLEX-RN preparation.” Ed.D., Capella University, 2016.

Campbell, Arthur J. “Contemporary Canadian Repertoire for the Unaccompanied Clarinet.” D.M.A. diss., Northwestern University, 1995.

Cargill, Jimmy Alan. “The Relationship Between Selected Educational Characteristics of Band Directors and their Acceptance and Use of Comprehensive Musicianship.”Ph.D. diss., University of Houston, 1986.

Curlette, William B. “New Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet by Soviet Composers.” D.M.A. diss., The Ohio State University, 1991.

Di Santo, Christopher Alan. “Improvisatory Affect in Selected Unaccompanied Clarinet Works of Meyer Kupferman.” D.M.A. diss., Temple University, 1996.

Ditto, Therese J. “Content-based curriculum versus concept-based curriculum: A retrospective causal comparative study to identify impact on the development of critical thinking.” Ed.D. diss., Capella University, 2014.

Edwards, Patricia Allen. “The Effects of a Concept-Based Curriculum on Nursing Students' NCLEX-RN Exam Scores.” Ed.D. diss., Walden University, 2015.

Fernandez, Loretta. “Learning Another Language with Conceptual Tools: An Investigation of Gal'perin's Concept-Oriented Instruction.” Ph.D. diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2017.

Fisher, Huot. “A Critical Evaluation of Selected Clarinet Solo Literature Published from January 1, 1950 to January 1, 1967.” D.M.A. diss., University of Arizona, 1970.

Fogal, Gary G. “Pedagogical stylistics and concept-based instruction: An investigation into the development of voice in the academic writing of Japanese university students of English.” Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto, 2015.

Fukunaga, Sallie Diane Price. “Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet by Contemporary Latin American Composers.” Ph.D. diss., University of Kansas, 1988.

Garcia Frazier, Elena. “Concept-based teaching and Spanish modality in Heritage language learners: A Vygotskyan approach.” Ph.D. diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2013.

Harsian, Cosmin T. “Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet.” D.M.A. diss., University of Kansas, 2009.

Heavner, Tracy Lee. “An analysis of beginning band method books for principles of comprehensive musicianship.” Ph.D. diss., University of Northern Colorado, 1995.

Johnson, John Paul. “An investigation of four secondary level choral directors and their application of the Wisconsin Comprehensive Musicianship through Performance approach: A qualitative study.” Ph.D. diss., The University of Wisconsin - Madison, 1992.

Johnson, Neil Howard. “Genre as concept in second language academic writing pedagogy.” Ph.D. diss., The University of Arizona, 2008.

Kim, Jiyun. “Developing Conceptual Understanding of Sarcasm in a Second Language Through Concept-Based Instruction.” Ph.D diss., The Pennsylvania State University, 2013.

Laverty, Grace Elizabeth. “The Development of Children's Concepts of Pitch, Duration, and Loudness as a Function of Grade Level.” Ph.D. diss., The Pennsylvania State University, 1969.

Matthys, Herbert A. “New Performance Techniques in Selected Solo Clarinet Works of William O. Smith, John Eaton, Donald Martino and Paul Zonn.” D.M.A. diss., Indiana University, 1982.

Nielsen, Ann. “Concept-Based Learning in the Clinical Environment.” Ph.D. diss., University of Northern Colorado, 2013.

Odom, David H. “A Catalog of Compositions for Unaccompanied Clarinet Published Between 1978 and 1982, with an Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works.” DMA diss., Florida State University, 2005.

Polizzi, Marie-Christine. The development of Spanish Aspect in the Second Language Classroom: Concept-Based Pedagogy and Dynamic Assessment. Ph.D. diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2013.

Romanek, Mary Louise. “A Self-Instructional Program for the Development of Musical Concepts in Preschool Children.” Ph.D. diss., The Pennsylvania State University, 1971.

Schoepflin, Howard J. “Stylistic, Technical, and Compositional Trends in Early Twentieth-Century Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet.” D.M.A. diss., North Texas State University, 1973.

Scruggs, Tara. “An Annotated Bibliography of Original Music for Solo Clarinet Published Between 1972 and 1977.” D.M.A. diss., Florida State University, 1992.

Shaw, Gary Richard. “A Comprehensive Musicianship Approach to Applied Trombone Through Selected Music Literature.” D.M.A. diss., The University of Wisconsin - Madison, 1984.

Sindberg, Laura K.. “Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance (CMP) in the Lived Experience of Students.” Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 2006.

Sitarz, Jane Margaret. “An analysis of elementary education majors' and music majors' experiences with comprehensive musicianship principles in high school general music classes.” Ph.D. diss., University of Maryland College Park, 2010.

Sperazza, Rose U. “Edward Yadzinski: His Life and Works for Unaccompanied Clarinet.” D.M.A. diss., University of Wisconsin – Madison, 2004.

Starling, Jana. “Comprehensive Musicianship: A clarinet method book curriculum and sample units.” D.M.A. diss., Arizona State University, 2005.

Stier, John Charles. “A Recorded Anthology of Twentieth-Century Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet.” D.M.A. diss., University of Maryland, 1982.

Sykes, Charles E. “A conceptual model for analyzing rhythmic structure in African-American popular music.” D.M.A. diss., Indiana University, 1992.

Whitener, William Thomas. “An Experimental Study of a Comprehensive Approach to Beginning Instruction in Instrumental Music.” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1980.

Woods, David Gay. “The Development and Evaluation of an Independent School Music Curriculum Stressing Comprehensive Musicianship at Each Level, Preschool Through Senior High School.” Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 1973.

Scores

Cuong, Viet. Zanelle. New York City: Viet Cuong Music, 2009.

Other

“Abdominal Muscles,” Dr. Russell Schierling Website, last modified 2018, accessed March 20, 2018, http://www.doctorschierling.com/blog/scar-tissue-of-the-abdominal-muscles.

“Biography,” Elliott Del Borgo Website, last modified January 1, 2015, accessed November 8, 2017, http://www.elliotdelborgo.com/bio.html.

“Biography,” Sven-David Sändstrom Website, last modified September 2011, accessed November 29, 2017, http://svendavidsandstrom.com.

“Biography,” Viet Cuong Website, last modified June, 2017, accessed November 28, 2017, http://vietcuongmusic.com/about.

Comprehensive Musicianship: An Anthology of Evolving Thought.

Music Educators National Conference, Washington, DC. Contemporary Music Project: Contemporary Music Project/Music Educators National Conference, 1971.

Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance: The Foundation for College Education in Music. Music Educators National Conference, Washington, DC. Contemporary Music Project: Contemporary Music Project/Music Educators National Conference, 1965.

“David Etheridge,” World Clarinet Alliance, last modified January 15, 2013, accessed November 8, 2017, https://www.wka-clarinet.org/VIP-Etheridge.htm.