Abstract

Soprano Jenny Lind (1820–87), known as the “Swedish Nightingale,” toured the United States in 1850 under the auspices of “America’s Greatest Showman” and self-proclaimed “Prince of Humbug,” P. T. Barnum (1810–91). The tour was a phenomenal success for both of them and made Lind perhaps the most famous person on earth that year. This article presents historical information, pictures, documents, and commentary about these two historical figures and their relationship. It also offers critiques and descriptions of her singing, alongside corresponding recordings of the music she sang. Because there was no recording technology invented during Lind’s lifetime, these modern recordings by other singers are used to bring her singing to life.

A story taken from the histories of music and business reveals a unique combination of high art, opportunity, commercialism, and social consciousness. It involves the unlikely pairing of two distinctly different characters. One, the famous soprano Jenny Lind, was born unwanted into humble circumstances and pulled herself up through talent, determination, and hard work to become one of the world’s most revered singers. The other, P. T. Barnum, was born into a family of farmers and shopkeepers and pulled himself up through ambition and creativity to become one of the world’s most successful business entrepreneurs. Their lives converged in a story of music, excitement, money, and charity seldom seen before or since. The benefits of their collaboration reach beyond their enthralled audiences to the successful management and marketing of touring artists today. Together, they initiated a cultural change in arts appreciation and philanthropy extending into the twenty-first century.

Known as the “Swedish Nightingale,” Lind toured the United States in 1850 under the auspices of Barnum, known as “America’s Greatest Showman” and self-proclaimed “Prince of Humbug.” The tour was a phenomenal success for both of them and made Lind perhaps the most famous person on earth that year. This article presents information, pictures, documents, and commentary about these two historical figures. It likewise critiques and describes Lind’s singing, and offers corresponding recordings of the music she sang. Since there was no recording technology available during her lifetime, these modern recordings by other singers are used to bring her singing to life.

Jenny Lind

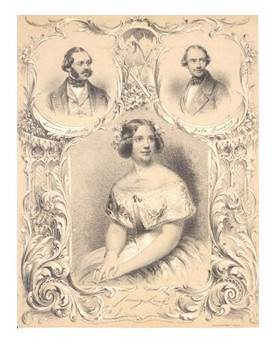

Figure 1. Jenny Lind (Jenny Lind Images 2019)1These images show a portrait signed and dated in Jenny Lind’s handwriting, and the same portrait appearing on the Swedish 50 Kroner bill.

Jenny Lind’s beginnings were far from auspicious. She (1820–87) was born the out-of-wedlock daughter of a divorced woman. At that time, tremendous stigma was attached to both out-of-wedlock births and divorce.2Anders Brändström (1999, 94–95) claims that in Sweden from 1811–20, only 6.2 percent of all births were illegitimate, explaining that “[i]n the eyes of the Swedish Protestant church[,] the mother of an illegitimate child was not ‘pure’ . . . [and] was obliged to face the minister and admit her sins.” By contrast, as stated in Statistics Sweden (2015), the Swedish governmental agency responsible for official statistics in that country, “[m]ost of the children In Sweden [as of 2015] are born out of wedlock[,] and this has been the case since 1993. . . In 2013, 54.4 percent of the children were born to an unmarried mother.” In the mid-nineteenth century, divorce was opposed by both church and state. There was statistically only one divorce per 5,000 marriages (Lundh 2003, 11). By comparison, as of 2018, “28 percent of people born to Swedish parents had divorced” (Kauffman 2018, 1). Her mother Anna Marie Fellborg, divorced from her husband due to his adultery, was already supporting a daughter with earnings from the school for girls she had opened. Subsequently befriended by Niklas Lind, a young bookkeeper and ne’er-do-well tavern goer, Fellborg became pregnant with his child. Her religious beliefs prevented her from marrying him because, although divorced, she maintained fidelity to her marriage until the death of her ex-husband years later. Fellborg hid her pregnancy by prolonging summer vacation and opening her school a bit late in the fall after giving birth to a new daughter on October 6. She immediately sent the baby to the home of her cousin and his wife, who were living in a nearby town. When Fellborg occasionally came to visit her cousin’s home, she was known as Aunt Anna Marie. Four years later, her cousin’s wife died, and the little girl had to be returned to her birth mother.

Fellborg’s older daughter, thirteen-year old Amelia, welcomed the four-year-old into the family and became her self-appointed mother. “Uncle Niklas,” or “Papa Niklas” as Niklas Lind referred to himself in his relationship with the littlest girl, doted upon her. He was frequently around the home singing and playing the guitar, and all the students at Fellborg’s school were fond of him. By contrast, Fellborg herself was ill-tempered and often verbally abused her younger daughter. Ironically, no one knew the embarrassing awkwardness of her relationship with the little girl.

Eventually, the little girl’s grandmother took her in order to live with her in the Stockholm Widow’s Home. They formed a close relationship, and both of them endured the mother’s bouts of ill temper. A devout Lutheran, the grandmother provided a refuge for the little girl, instilling in her both a sense of purpose and charity that would stay with her for the rest of her life. It was her grandmother who started calling her Jenny, instead of her given name of Johanna Marie. It was also her grandmother who noticed her love for music, and was astounded when she discovered that Jenny likewise had superb aural skills, having just played a fanfare on the piano after she had heard a military band from her window marching down the street below.3Musical notation of the fanfare appears in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 1:16). Jenny had hid under the piano for fear of punishment, but her grandmother instead praised her and asked how she had done it. She responded by saying, “I felt the music in my fingers” (Shultz 1962, 26). Jenny also sang incessantly around her home, just for fun.

When Jenny was nine, a maid at the home of a dancer from the Royal Theater overheard her singing and told her mistress, who then recommended to the Theater School’s directors that Jenny be admitted as a student. Initially, she was refused an audition because she was too young, but then the director “consented to hear [her] sing, and, when she sang, he was moved to tears and, from that moment, she was accepted and was taken, and taught to sing, and educated, and brought up at . . . Government expense” (Holland and Rockstro 1891, 1:17–18).4This portion of her history is recorded by her eldest son in 1887. But in order for a student to gain admission into the school, the signature of both parents was required. Only then did Jenny Lind’s mother Anna Marie have to reveal her daughter being born out of wedlock.

Lind’s own painful words at age thirty-one summarize her personal life, as confided to her future husband Otto Goldschmidt:

You did not know that I was born out of wedlock, but that is the truth. My mother had so little thought for me that she did not marry my father until I was a big girl, nearly fifteen, and then it was not for my sake, oh no. She sent me away as soon as I was born; she did not have me with her until she was forced to. She never let me know she was my mother until she was forced to. She never wanted me until I began to bring in money. Then she wanted only the money I brought in. You did not know that my father is nothing but a drunkard, who spends all his time in taverns until he gets so drunk someone must take him home. (Shultz 1962, 300)

Lind was a star pupil at the Royal Theater School. She excelled in dancing, acting, playing the piano, and singing, while also acquiring instruction at her mother’s school in religion, history, geography, writing, arithmetic, and drawing. She developed so quickly as a singer that the newspaper Heimdal (April 24, 1832) reported on her progress at age twelve:

Jenny’s remarkable musical gift and its precocious development . . . have made quite a sensation in the circle in which she has appeared, guided by her master, Herr Berg. Her memory is as perfect as it is sure; her receptive powers as quick as they are profound. Everyone is thus both astonished and moved by her singing. She can stand a trial of the most difficult [solfeggi], and intricate phrases, without being bewildered, and, whatever turns the improvisations of her master take, she follows, as if they were her own. If this young genius does not ripen too prematurely, there is every reason for expecting to find her eventually an operatic artist of high rank.5Quoted in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 1:49).

By age thirteen, Lind had already appeared as a performer twenty-two times. At seventeen, she had made her operatic debut, and at twenty-one, she had appeared over 400 times on the Royal Theater stage. By this time, Lind had already been given the nickname “The Nightingale” in the newspaper Correspondenten (Maude 1926, 12).

But Lind’s young voice became fatigued through overuse. She had outgrown the instruction of the Royal Theater School and wished to achieve higher artistic standards. A celebrated baritone Italian singer Giovanni Belletti (1813–90), who also sang at the Royal Theater, recommended that she study in Paris with the famous pedagogue Manuel Garcia (1805–1906). To Lind’s surprise and humiliation, when Garcia heard her, he refused to accept her as a pupil, declaring, “my dear, you have no more voice.”6"Mademoiselle, vous n'avez plus de voix" (Holland and Rockstro 1891, 1:11). Shocked and in anguish, Lind asked Garcia what to do. He advised her not to sing or even talk for six weeks and then come back to audition again. She did just that, and this next time he accepted her. Garcia said later: “I do not remember ever having had a more attentive, intelligent pupil. Never [did I have to] explain anything to her twice” (Pleasants 1966, 199). During her lessons with Garcia, Lind worked especially hard on breath control, vocal production, and evenness of register.

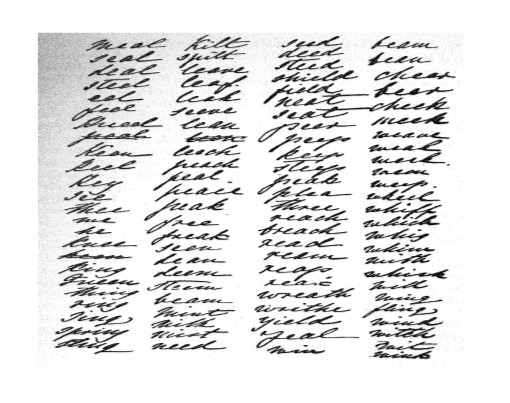

Lind also focused on language and diction. Her German teacher, Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer (1799-1868), “remembered that on one occasion she had left the house as Jenny was starting to practice the difficult word “zersplitter’ on a high B flat. Returning to the house several hours later[,] she found Jenny still practicing ‘zersplitter’ and she kept on until the short ‘I’ was open and perfect on the high note, something beyond the power of most German singers” (Shultz 1962, 128). A list in her handwriting shows English words she studied diligently in order to pronounce them correctly, such as meal, seal, deal, etc.

Figure 2. English Words in Jenny Lind’s Handwriting (Maude 1926, 191)

Figure 2. English Words in Jenny Lind’s Handwriting (Maude 1926, 191)

When Lind returned to Sweden a year later, the public was amazed to hear its Nightingale sounding even more beautiful than before. Her voice range was nearly three octaves, from B3 to G6 (Maude 1926, 128). Mrs. Raymond Maude—Lind’s daughter, in a biography of her mother—describes Lind’s singing at this time:

The pianissimo rendering of . . . high notes was one of the most remarkable features of her singing. It was as rich in power as her [mezzo-forte], and though falling on the ear like a whisper[, it] reached the farthest corner of theater or concert room. By nature her voice was not a flexible one; only perseverance and unremitting practice had made it so. Her breathing capacity was also not naturally great, but she renewed her breath so quietly and cleverly that the closest observer could not detect her doing it[,] and the outside world credited her with abnormal lung capacity. Her messa di voce, i.e.[,] the art of swelling or diminishing her voice from the softest [piano] to the full volume of its power and vice versa[,] was unrivalled by any singer. In like manner in her shakes, her scales, her legato, and staccato passages[,] she evoked astonishment and admiration no less from competent judges than from the general public (Maude 1926, 128–29).

Her teacher Manuel Garcia wrote that “one is struck with the cleverness with which she managed her breathing, the finish of her shake, her hold over her voice, and its immutable purity of tone, whether singing [mezza voce] or florid passages” (Holland and Rockstro 1891, 2:294–304).7Chapter 11 (Method) of Holland and Rockstro explains Lind’s vocal abilities and Garcia’s teaching in detail.

Descriptions of Lind’s singing by Europe’s finest musicians supply more information regarding her vocal artistry. Chopin said in a letter to a friend that “[t]his Swede is an original from head to foot. She does not show herself in the ordinary light, but in magic rays of the aurora borealis. Her singing is infallibly pure and true, but, above all[,] I admire her ‘piano’ passages, the charm of which is indescribable” (Maude 1926, 105). Clara Schumann likewise described Lind’s singing in glowing terms:

Lind has a genius for song which might come to pass only once in many years. Her appearance is arresting at first glance and her face, although not exactly beautiful, appears so because of the expression in her wonderful eyes. Her singing comes from her inmost heart; it is no striving for effect, no passion which takes hold of the hearer, but a certain wistfulness, a melancholy, which reaches deeply into the heart . . . . At the first moment she might appear to one as cold, but this is not so at all; the impression is caused by the purity and simplicity which underlies her singing. There is no forcing, no sobbing, no tremolo in her voice, not one bad habit. Every tone she produces is sheer beauty. Her coloratura is the most consummate I have ever heard. Her voice is not large in itself, but would certainly fill any room, for it is all soul. (Shultz 1962, 127)

Mendelssohn also appreciated Lind’s vocal artistry, stating that “[t]here will not be born, in a whole century, another being so gifted as she” (Shultz 1962, 125).

Queen Victoria took the time to write in her diary about Lind, remarking that “[s]pecial mention is made of the unrivalled charm of the Swedish songs, sung to her own accompaniment, the effect of the softness and finish being extraordinary and almost stunning” (Maude 1926, 95). And also: “It was all piano and sweet, like the singing of the zephyr; yet all clear. Who could describe those long notes drawn out till they melt quite away; that shake which becomes softer and softer, and those flute-like notes, and those round fresh tones which are so youthful!” (Shultz 1962, 118).

Lind’s operatic career blossomed, and she appeared in opera and concert houses in Berlin, Leipzig, Vienna, and London. By age twenty-nine Lind had sung operatic roles in nearly 700 performances.8Holland and Rockstro (1891, 2:305) present a complete list of Lind’s operatic roles. A renowned star, she nevertheless found opera tiring. At that point in her career, she wanted to stop performing operatic roles and instead sing only concerts.

P. T. Barnum

On the other side of the world, Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810–91), the self-proclaimed “Prince of Humbug,” used his talents for publicity, investment, excitement, and a feel for the uncanny to entertain the public. A childhood of farming, shopkeeping, trickery, and creativity prepared him for a future of entrepreneurial showmanship. One example of shrewd dealings as a store clerk at age fifteen had Barnum trading some unsalable store items for a peddler’s wagonload of green bottles, and then advertising a lottery game in which there would be 500 winners for the 1000 tickets sold. Long story short, he ended up with zero of those unwanted green bottles, which were awarded as prizes, and he got rid of those unsalable store items, ending up with plenty of money collected from the lottery tickets (Barnum 1927, 53–56). He explained that “My disposition is and ever was, of a speculative character, and I am never content to engage in any business unless it is of such a nature that my profits may be greatly enhanced by an increase of energy” (Harris 1973, 13).

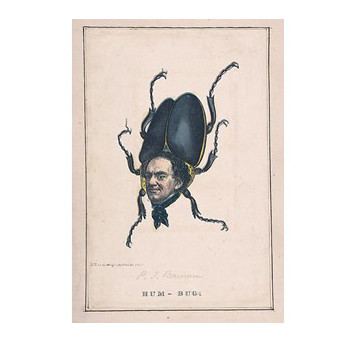

Barnum mused about his self-descriptive term, the “Prince of Humbug,” and stated the following: “Webster says that humbug, as a noun, is an ‘imposition under fair pretences’; and as a verb, it is ‘To deceive: to impose on.’ With all due deference to Doctor Webster, I submit that, according to present usage, this is not the only, nor even the generally accepted[,] definition of that term”(Cook 2005, 94).9Another definition of humbug comes from a Wikipedia website (2019): “A humbug is a person or object that behaves in a deceptive or dishonest way, often as a hoax or in jest. The term was first described in 1751 as student slang, and recorded in 1840 as a "nautical phrase." It is now also often used as an exclamation to mean nonsense or gibberish.” Barnum gave examples of this train of thought, contrasting evil forging, pickpocketing, swindling, and cheating with good-natured spoofing and trickery. He justified his activities by saying that “I don’t believe in ‘duping the public,’ but I believe in first attracting and then pleasing them” (Kunhardt 1995, 47). He defended his “humbugging” by pointing to audience satisfaction and their entertainment at being humbugged. Any publicity was better than none. A ticket seller for one venture said: “First he humbugs them, and then they pay to hear him [explain] how he did it. I believe if he should swindle a man out of twenty dollars, the man would give [him] a quarter to hear him tell about it” (Harris 1972, 77). He proudly proclaimed himself as the Prince of Humbug and became so well known that in 1851, H. L. Stephens even painted a caricature of him as a literal bug, an insect (Figure 3).

Figure 3. P. T. Barnum, the Prince of Humbug (PT Barnum Images 2019)10PT Barnum Images-hum bug includes "Hum-Bug," the cartoon by H. L. Stephens (1851).

Barnum’s career was astounding. His activities have influenced cultural norms in the two centuries since his birth. He revolutionized popular culture through his museum and as an impresario through his efforts in publicity, marketing, and showmanship, all of which is unsurpassed to this day (Brown and Hackley, 292).

Figure 4. Joice Heth, the 161-year-old Slave Nurse of George Washington (PT Barnum Images 2019)

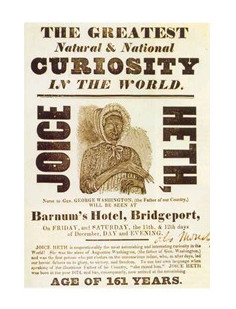

Barnum first gained attention with traveling exhibits through the unsavory use of Joice Heth, an enslaved African-American woman (Figure 4). He rented her from a Kentucky friend who owned her and was “trumpeting [her] around Philadelphia as the 161-year-old former nurse of George Washington” (Mansky 2017; see also Adams 1997, 6). In 1835, Barnum successfully displayed Heth at Niblo’s Garden in New York City and then took her on a profitable tour all over the east. He found the public eager to see and meet this “freakishly old woman.” He remarked how he “taught Joyce . . . a few anecdotes of Washington [as] a boy . . . which Joyce became quite perfect in, after some good drilling” (Cook 2005, 26).11Barnum also says that “I discovered her weak point. It was discovered in seven letters—W-H-I-S-K-E-Y . . . and for a drop of it, I found I could mould her to anything” (Cook 2005, 24). When Heth died two years later, Barnum thought of yet another money-making scheme: he sold tickets to 1,500 spectators at fifty cents per ticket [$15 in 201912Dollar Inflation Calculator, https://www.officialdata.org. All dollar conversions in this article come from this website. ] to witness her autopsy performed in the New York Saloon (Mansky 2017 and Cook 2005, 48–49). Her age of 161 proved to be a grand hoax, as the autopsy revealed that she was “seventy five, or at the utmost, eighty years of age!”13The New York Sun, February 26, 1836, quoted in Cook 2005, 52. Far from ruining Barnum’s career when he was caught in such an egregious lie, he gained notoriety that propelled him into additional—as well as profitable—humbuggery.

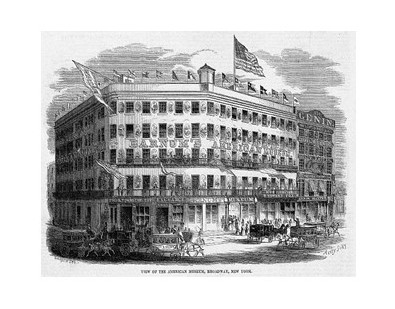

Figure 5. Barnum’s American Museum, New York City (P. T. Barnum Images 2019)

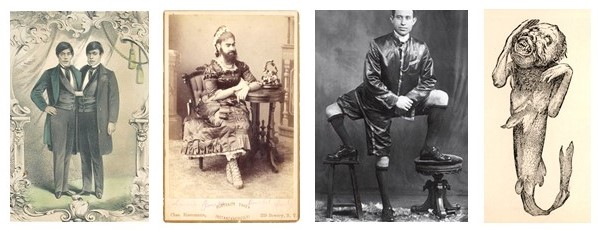

A few years later, Barnum purchased the Scudder Museum after its owner died. It housed various specimens, such as an American bison, an 18-foot snake, a lamb with two-heads, miscellaneous curiosities, and the first American flag hoisted over New York City on the day the British departed.14“Scudder’s American Museum,” Wikipedia 2019. Barnum opened his new purchase as the American Museum on January 1, 1842 at a ticket price of twenty-five cents per visitor [$7.75 in 2019] (Figure 5). In addition to the exhibits already there, he expanded his offerings to include more attractions (Figure 6), such as Chang and Eng the Siamese Twins, a Bearded Lady, a three-legged man, and the Fejee Mermaid (humbug—a bogus combination of two stuffed specimens). Appalling as this would seem in the twenty-first century, Barnum’s marketing in his popular freak shows of people born with abnormalities was highly successful. Indeed, these people voluntarily agreed to be displayed, were paid for doing so, and some even became wealthy. The Museum also provided natural history exhibits, social history, drama and more. It was a respectable venue to a wide range of social classes.

Figure 6. Siamese Twins, Bearded Lady, Three-legged Man, Fejee Mermaid (PT Barnum Images 2019)

The same year in which Barnum opened the American Museum, he noted that he had heard of “a remarkably small child in Bridgeport[, CT] . . . . ” Barnum goes on to say that he “was the smallest child I ever saw that could walk alone. He was not two feet in height, and weighed less than sixteen pounds. He was a bright-eyed little fellow, with light hair and ruddy cheeks, [and] was perfectly healthy . . . ” (Cook 2005, 57). This small child was Charles Stratton. Barnum discovered him at age five, renamed him General Tom Thumb, and paid his parents $3 per week [$93 in 2019] to be on display at the American Museum.15By the time Tom Thumb reached the age of fourteen, Barnum was paying him $10,400 per year (approximately $350,000 in 2019). See P. T. Barnum (1852).

Tom Thumb captivated audiences by singing assorted songs, such as “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” in his high, clear voice, posing as Napoleon or Cain or a Scottish Highlander, and performing a hornpipe dance or a blackface routine. He was enormously popular. Barnum began to wonder about the amusement prospects in London and then ventured in 1844 to Europe with Tom Thumb in tow, along with his parents, a tutor, and others (McCullough 2011, 161).

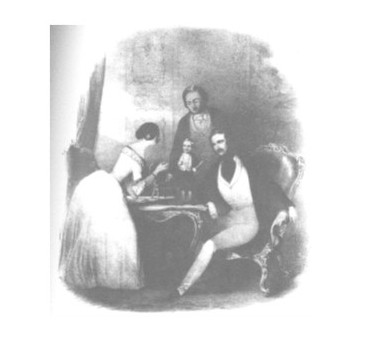

In Europe, General Tom Thumb performed for dignitaries the likes of whom Barnum had never met before. He describes one visit: “Last night the Baroness Rothschild sent her carriage for us. We spent two hours in her mansion, which eclipses everything in the shape of luxury that I have ever seen. Some twenty lords and ladies were present, and on taking our leave an elegant purse, containing twenty sovereigns [$2500 in 2019], was quietly slipped [into] my hands—. . . good evidence of the high favor in which Tom Thumb stands in London among the nobility.” And a bit later he states: “I have been twice with Tom Thumb before Queen Victoria, at Buckingham Palace, . . . have exhibited the General to the Queen of Belgians, Prince Albert, the Duchess of Kent, the Prince of Wales, the young Princess Royal, the Duke of Wellington, and thousands of nobility . . .” (Cook 2005, 61–63). Through these visits he became enthralled with a segment of society not present in America (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Tom Thumb Performing for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert16This engraving is housed in the Bridgeport Public Library. Photo and citation are in Kunhardt (1995, 57, 357). The name of Tom Thumb’s handler—in the background—is unknown.

Barnum also visited Paris to see the Grand Exposition, the gigantic fair on the Champs-Élysees taking place once every five years. Thrilled by the exposition, he later made subsequent trips to Europe to collect curiosities for his American Museum and to ponder new exhibits. A significant impression for him was that “a New Yorker soon begins to look upon Gotham [New York City] as a little village” (Cook 2005, 61).

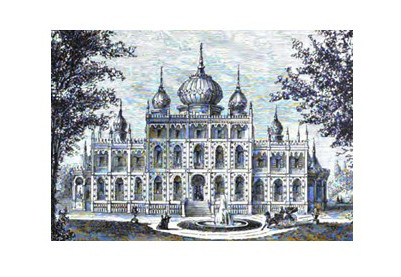

Following several visits to Europe and quite a few successful years at the American Museum, Barnum decided to build himself a luxurious mansion he dubbed “Iranistan” in Bridgeport, CT (Figure 8). He purposely built it close enough to the railroad tracks so that everybody could see it on the way to New York City. After two years of construction, Barnum opened it to the public on November 14, 1848. It contained his family’s living quarters and, more importantly, presented to the public a mansion the likes of which had never before been seen in America. Its design was inspired by King George IV’s oriental-themed Royal Pavillion at Brighton, hence it is no surprise that it was given an exotic-sounding name (Kunhardt 1995, 84). Iranistan would prove significant in Barnum’s later negotiations with Jenny Lind to bring her to the US. She commented to Barnum on a letter from his agent written upon a sheet headed with a beautiful engraving of Iranistan: “It attracted my attention. I said to myself, a gentleman who has been so successful in his business as to be able to build and reside in such a palace cannot be a mere ‘adventurer.’ So I wrote to your agent, and consented to an interview, which I should have declined, if I had not seen the picture of Iranistan!” (Barnum 1927, 349).

Figure 8. Iranistan (PT Barnum Images 2019)

Tour of America

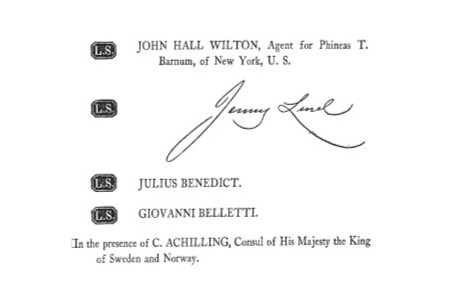

In 1847, Barnum had noticed news coverage of an extraordinary singer known in Europe as the Swedish Nightingale. He perceived that she was “the toast of Europe, [and] Queen Victoria’s favorite” (Kunhardt 1995, 84). With the American Museum a huge ongoing success and Iranistan nearly completed, Barnum pondered a new angle on his business ventures. He wondered about the possibility to “remake his image from humbug to serious promoter of the arts” (Kunhardt 1995, 88). Ignorant about classical music, Barnum nevertheless perceived that Jenny Lind was a phenomenon in Europe and he wondered if she might prove a profitable phenomenon in the US as well. He reflected on this prospect: “It was an enterprise never before or since equaled in managerial annals. As I recall it now, I almost tremble at the seeming temerity of the attempt. . . . I risked much but I made more” (Barnum 1927, 318). Without even meeting her, Barnum sent a representative to Europe to present Lind with a contract for an American tour (Figure 9). After some negotiating, Lind accepted a plan that included a huge sum of money to be deposited in advance into a London bank for 150 concerts; salaries for conductor/composer/pianist Julius Benedict and for accompanying singer Giovanni Belletti (Figure 10), the man who had recommended that she study with Manuel Garcia; expenses for her maid and a male companion (as required by Swedish law for unmarried females); and travel, hotels, and carriage and horses at each locale. She would sing at least two concerts at each venue, performing at least four songs each time she appeared. Beyond that, Lind would be allowed to sing as many charity concerts as she liked. The sums earned were staggering, amounting in today’s dollars to approximately $32,000 per concert to Lind and a total of $80,000 to Benedict and $40,000 to Belletti for the entire American tour.17The contract also stipulated that if the total promised amount was earned and all expenses paid by the 75th concert, Barnum would then pay her 20% of the ensuing receipts, provided that he had cleared at least ₤15,000 (approximately $2,550,000 in 2019). Further financial details appear in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 2:366–68). See websites listed below for pound to dollar conversion and dollar inflation calculator. Barnum decided to promote Lind differently than his past acts. According to Bluford Adams, he “packaged [her] as the ultimate sentimental heroine. . . .Their strategy produced a tour notable for its popularity among the middle class” (Adams 1997, xiv).

Figure 9. Contract for American Tour with P. T. Barnum (Barnum 1927, 325)18Details of the contract and its negotiations appear in Barnum (1927, 318–28) and in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 2:364–69).

Figure 10. Julius Benedict, Giovanni Belletti, Jenny Lind (Jenny Lind Images 2019)

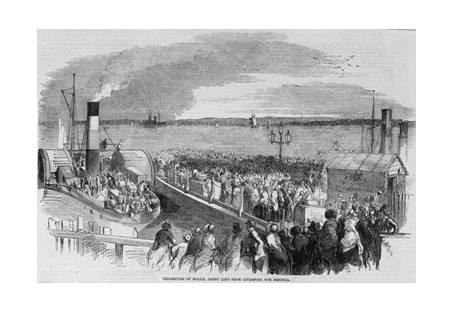

Lind and her retinue left Liverpool amid a tremendous farewell and traveled to New York aboard the steamship Atlantic (Figure 11). There she received an even more tremendous welcome, which was masterminded by Barnum (Figure 12). He had salted the newspapers with news about her arrival to provoke excitement. And he had salted the crowds with an army of his men carrying bouquets. His goal was to keep the hysteria high. Lind greeted the throngs from atop the ship’s paddle wheel and then made her way through two garlanded archways proclaiming, “Welcome Jenny Lind! Welcome to America!” A parade of thousands accompanied her to her hotel (Barnum 1927, 332).

Figure 11. Jenny Lind’s Departure from Liverpool, August 1850 (Ware 1980, 70)19Photo, Illustrated London News, August 24, 1850.

Figure 12. Jenny Lind’s Arrival in New York City, September 1850 (Ware 1980, 70)20Photo, Ladies Home Journal, November, 1896.

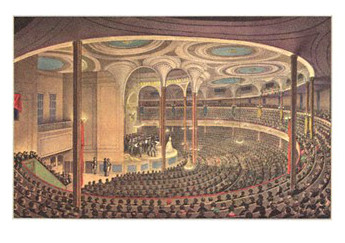

Lind, Barnum, Benedict, and Belletti inspected various concert halls and opera houses in New York City and chose Castle Garden for the first concert (Figure 13). It could accommodate thousands and had good acoustics. An orchestra of local musicians was selected. Nominally priced tickets were auctioned off to the highest bidders, and the first ticket was won by Genin the Hatter, whose store was next door to Barnum’s American Museum. (With some advance coaching from Barnum as to the attention to be gained, Genin “laid the foundation of his fortune by purchasing the first ticket” [Barnum 1927, 337]21According to the Wikipedia website (2019), John Nicholas Genin (1819–78) was so famous for making hats that folks everywhere (especially after the Lind ticket-sale episode) would take off their hats to check whether or not they were wearing "a Genin." ) The concert was a grand success and required five more performances in the same location. Thousands of dollars were earned, and thousands of admirers got to hear the Swedish Nightingale.22Lind writes home to her parents: “We rarely make less than $10,000 [approximately $325,000 in 2019] at a concert. . . . My share for six concerts is $30,000 [$978,000]!” She also recounts that the first ticket was auctioned for $625 ($20,000; see Holland and Rockstro [1891, 2:418–20]). After that first concert, Lind insisted that at least some tickets be made available for ordinary audience members (without auction) at $1 and $2 ($33 and $66). See Jenny Lind Tour 2019. In a brilliant move after the first concert, Barnum announced to the audience that the entire sum would be donated to charity. The combination of Lind’s beautiful singing and the charitable donation sealed her fate and Barnum’s in an incredibly successful American tour. “'Lindomania' pervaded the country by means of countless souvenirs, in the form of Jenny Lind gloves, bonnets, riding hats, shawls, mantillas, robes, chairs, sofas, and pianos” (Barnum 1927, 333).

Figure 13. Castle Garden, New York City, Jenny Lind’s First Performance in the US, September 11, 1850 (PT Barnum Images 2019)

The concert program found below (Figure 14) would be typical of those throughout Lind’s American tour, namely various pieces performed by members of her entourage and local musicians, and numbers sung by her drawn not only from her most famous operatic roles but also folk songs in which she accompanied herself at the piano.

PROGRAMME OF MLLE. LIND’S FIRST CONCERT IN AMERICA

Castle Garden, New York, 11th September, 1850

GRAND OVERTURE, Oberon Weber

AIR from Maometto Rossini

Signor Belletti

Casta Diva Bellini

Mlle. Lind

Grand Duet for Pianoforte Airs by Bellini

Messrs. Benedict and Hoffman

Turco in Italia Rossini

Duet, Mlle. Lind and Signor Belletti

Orchestral Overture, “The Crusaders” Benedict

TRIO from The Camp of Silesia Meyerbeer

Mlle. Lind and Flautists

(Messrs. Kyle and Siede)

Largo al Factotum Mozart

Signor Belletti

“Herdsman’s Song” (known as “The Echo Song”) Swedish Melody

Mlle. Lind

“Greetings to America,” words by Bayard Taylor Benedict

Mlle. Lind

Figure 14. Jenny Lind, First Concert in the US, Castle Garden, New York City, September 11, 1850

The final song, “Greetings to America,” was composed expressly for the occasion. It was the winning text of a competition devised by Barnum to submit poems in honor of Lind’s arrival, which would then be set to music by conductor/composer Julius Benedict and performed at the first concert.23Barnum (1927, 334) includes the complete poem.

Example 1. Greetings to America Excerpt24Greetings to America; text by Bayard Taylor, composed by Julius Benedict (Parcells, 1989).

Favorites among American audiences were the folksongs. Most audience members were ordinary citizens rather than sophisticated opera goers, and they were attracted just as much by Lind’s fame and glory as by the music itself. Lind’s choice of repertory proved immensely appealing.25In today’s music world, concerts successfully combine high art with popular styles, which was unusual in Jenny Lind’s time. Alex Ross discusses “Popular Music” versus “Classical Music . . . by Implication, Unpopular Music” in an engaging article in the New Yorker (2004, para. 3).

Especially beloved was the “Echo Song,” which featured a peasant herding his flock and the mountains echoing back.26Maude (1926, 160–61) explains that “the famous ‘Echo Song’ is a Norwegian melody, and the “Herdman’s Song” was written by Mlle. Lind’s singing master, Berg. Both of them were constantly sung by Mlle. Lind. Mr. Barnum . . . probably, at that date[,] did not know the difference, and Mlle. Lind is not likely to have seen the proofs of the programme.” An audience member wrote about the song to a friend:

In my wildest fancy, I had never imagined anything like it. It was a new revelation of the capability of the human voice, and appeared to all a miracle. The instantaneous echo of her own voice by an inhalation of the breath, to a full gush of melody poured from the lips, and this produced many times in succession, was something beyond my anticipations . . . . [W]ith her voice she would give us the bellowing of the cow, the Herdsman calling, . . . and off yonder in the mountains we could hear the echo which was of the sweetest and wildest melody that ever was listened to by the ears of man (Ware 1980, 24–25).

Lind’s rendition was often described as a sort of ventriloquism, and she would typically turn her face to the audience, away from the piano, which she herself was playing, to render the echo.

Example 2. Echo Song Excerpt (Söderström, n.d.)

The Herdsman’s Song was composed for Lind by Isak Berg, her singing teacher at the Swedish Royal Theater School, and features the unbelievably long pianissimo sustained tones for which she was noted.27The score of Berg’s Herdsman’s Song is included in Holland and Rockstro (1891, Appendix, 19–20).

Example 3. Herdsman's Song Excerpt.mp3 (Söderström, n.d.)

The folk-like “Bird Song” (not listed on the program), composed for Lind by German composer Wilhelm Taubert (1811–91), features sublimely virtuosic trills and arpeggios that thrilled audiences. Expressing her admiration for the song, Lind wrote the following words to a friend: “If you see Taubert, tell him, please, that they will not listen to anything here but his song. . . . I have to sing it at every concert” (Ware 1980, 37).

Example 4. Bird Song Excerpt.mp3 (Parcells 1989)

The trio for two flutes and soprano from Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Camp in Silesia (Ein Feldlager in Schlesien, 1844) was astounding. The opera itself, and indeed Meyerbeer’s other operas as well, was unknown in the US. This trio from its last act is a virtuosic showstopper.28This trio was written especially for Lind. The opera is a Singspiel with a somewhat historical plot featuring the flute-playing King Frederick the Great of Prussia (for whom J. S. Bach composed The Musical Offering). The plot involves the king trying to escape from Hungarian soldiers in Silesia (now southern Poland). A clever switch of the flute-playing character Conrad for the flute-playing king helps him escape. As a reward, Conrad is granted permission to marry the girl he loves, Vielka the gypsy. The trio in the last act features the King and Conrad, flutists, and Vielka the gypsy, a soprano. The same enthusiastic letter writer from the first concert exclaimed: “She accompanies two flutes, and as she motions her sweet little fingers, as though she was performing on a flute, you cannot distinguish the difference[,] so greatly does her voice resemble the sweetest notes you ever heard upon that instrument. [If you did not notice], you would imagine that there were three flutes” (Ware 1980, 24).

Example 5. Meyerbeer Trio Excerpt 1

Example 6. Meyerbeer Trio Excerpt 2 (Sutherland 2008)

Lind’s tour with Barnum proceeded initially down the East Coast, from New York to Boston, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Richmond, and Charleston, ending up in Havana, Cuba. The tour then went up the Mississippi River, from New Orleans to Natchez, Memphis, St. Louis, Nashville, Louisville, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh, before visiting New York and Philadelphia again, as well as many other smaller venues along the way (Jenny Lind Tour 2019). At each locale, Barnum sent advance publicity in order for throngs of admirers to await each arrival. Lind sang in concert halls and also whatever other venues proved large enough to house the audiences that inevitably emerged, thanks to Barnum’s masterful management. Little is known of the exact arrangements. Surely much was improvised on the spot, such as ticket sales, auctions, rentals of venues for extra concerts, precise timing of events and logistics, transportation, and security. Barnum’s flamboyant impromptu style contrasts with today’s more formal business practices of concert management, full of written contracts, legalities, rights and privileges of artists, workers, and attendees.

In his essay entitled “Our history: ‘Greatest Showman’ Barnum and singer Lind put on show for the ages,” Jeff Suess (2018) provides an inkling of what went on during Lind’s concert tour while in Cincinnati:

Lind and Barnum stayed in a suite of rooms at the Burnet House, the finest hotel of the day, at Third and Vine streets Downtown. The elegant rooms were thereafter marked with a plaque as the “Lind Suite.” On April 14, Lind gave the first of four concerts at the National Theater on Sycamore Street, north of Third Street. Demand was so high that Barnum held auctions for tickets. The Enquirer reported that Ezekial McElevey, a merchant tailor, bid $575 [$19,000 in 2019] for a single ticket. A crowd pressed against the theater windows hoping for a glimpse or a stray note. Barnum asked the police to intervene. When the throng would not disperse, they fired shots in the air. A local critic wrote, “Our expectations were not simply realized, but so far surpassed that we never before had any conception of angelic music until we heard Jenny Lind’s voice.”

Other accounts reveal that not all arrangements were entirely smooth. One concert nearly ended in disaster when the Fitchburg, MA railroad hall turned out to be too small for the number of tickets sold, and audience members who couldn’t get in rioted (Ware 1980, 39). In Havana, the most musically sophisticated audience that Lind encountered resented the high ticket prices posted by the “Yankee pirate” Barnum and hissed her appearance on stage. In response she advanced to the footlights and, in the words of Barnum,

[H]er countenance changed in an instant to a haughty self-possession, her eyes flashed defiance, and, becoming immovable as a statue, she stood there, perfectly calm and beautiful. She was satisfied that she now had an ordeal to pass and a victory to gain worthy of her powers. In a moment her eyes scanned the immense audience, the music began and then followed—how can I describe it?—such heavenly strains as I verily believe [no] mortal [ever] breathed except Jenny Lind, and [no] mortal [ever] heard[,] except from her lips. . . . Such a tremendous shout of applause as went up I never before heard. (Barnum 1927, 320)29Barnum quotes the Havana correspondence from the New York Tribune, but does not include the date.

Another near disaster occurred in Pittsburgh when the presenters unknowingly scheduled the concert on a Friday, which was payday for most people. The rowdies who traditionally got drunk on those Friday nights heckled Lind from outside to the point that nobody could hear her. She continued performing despite it all, but was compelled to escape with her company afterward through a back fence (Ware 1980, 39).

At every locale, Lind followed her concerts under Barnum’s management with charity concerts of her own. She donated vast sums of money to charity, some in her native Sweden and some in the US. A list of local charities receiving the $5,353.20 [$175,000 in 2019] in donations from one concert includes the Society for Improving the Condition of the Poor, Female Assistance Society, Eye and Ear Infirmary, Prison Association, Brooklyn Orphan Asylum, and fourteen more (Holland and Rockstro 1891, 2:427). She was beloved as much for her generosity and character as for her voice. Barnum remarks in his autobiography: “Although I relied largely on Jenny Lind’s reputation as a great musical artiste, I also took largely into my estimate of her success . . . her character for extraordinary benevolence and generosity. Without this peculiarity of her disposition[,] I should never have dared to make the engagement” (Barnum 1927, 331).

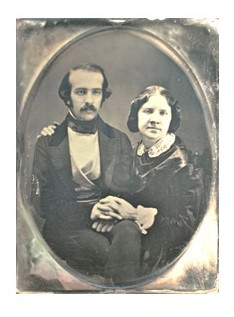

Eventually Lind and Barnum parted ways. She and her entourage were tired of the difficulties arising from his sensational management style. Lind’s pianist/conductor Julius Benedict eventually took a job at Her Majesty’s Theater in London and departed. Lind canceled her contract with Barnum according to terms they had specified before the tour began (Barnum 1927, 338 and 365). After 93 concerts of the 150 stipulated, she paid off the remaining expenses that would have ensued for the final concerts and proceeded under her own management to give more concerts in the US and Canada. Her exact itinerary is unknown, but she went from Philadelphia to Toronto and ultimately back to New York. The success of the final concerts was less than those managed by Barnum. A new pianist was needed. and Lind chose Otto Goldschmidt (1829–1907), whom she had met years earlier when he was a student of Mendelssohn and who had accompanied her in Germany. When he joined her tour in the US, they fell in love and were secretly married (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Mr. and Mrs. Otto Goldschmidt (Jenny Lind Images 2019)

Lind and Barnum remained on amicable terms. In his autobiography, Barnum wrote: “I met her several times after our engagement terminated. She was always affable. . . . I was always supplied with complimentary tickets when she gave concerts in New York, and on the occasion of her last appearance in America, I visited her in her room [backstage], and bade her and her husband adieu, with my best wishes. She expressed the same feeling to me in return” (Barnum 1927, 387). Lind and her company decided to leave the US. They presented their farewell concert on May 24, 1852, again at Castle Garden, before boarding the same ship with the same pilot who had brought them to America two years earlier. She sang her final program as Madame Goldschmidt, not Mademoiselle Lind, and the concert included “Farewell to America,” composed for the occasion by her husband.30To my knowledge, there is no score nor recording of “Greetings to America.” Apparently it was never published. Its words appear in Ware (1980, 134,) quoting the New York Tribune, May 27, 1852.

After they returned to Europe, Lind continued to sing, now using her married name of Goldschmidt, rather than Lind. She and her husband chose to live in London, where they were frequent guests of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. At this time she sang mainly for charity.31Lind especially channeled her donations toward endowments for free schools in Sweden. Scholarships funded by her endowments are administered to this day by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music (Jenny Lind, Wikipedia 2019). She taught at the Royal College of Music in London. She and Goldschmidt raised two sons and a daughter, who became Mrs. Raymond Maude, author of a biography of her mother, The Life of Jenny Lind (see the bibliography at end of this article).

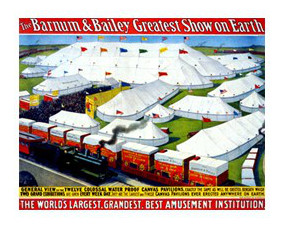

After Lind, Barnum no longer sponsored concert tours for musicians. Although he had endured slander, jail, fires, lawsuits and bankruptcies, Barnum somehow always achieved another success. After his American Museum in New York City burned down twice (1865 and 1868), he took to the road with Barnum’s Great Travelling World’s Fair and later joined forces with J. A. Bailey to form the Barnum and Bailey Circus, “The Greatest Show on Earth” (Figure 16).

Figure 16. “Barnum and Bailey Circus, The Greatest Show on Earth” (PT Barnum Images 2019)

Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale,.” died of cancer at the age of 67. P. T. Barnum commented about her death in his autobiography: “So dies away the last echo of the most glorious voice the world has ever heard” (Barnum 1927, 791). Three years later, Barnum died of a stroke at the age of 81. Before his death he had shown Lind’s grandchildren around one of his exhibitions when it traveled to Europe (Ware 1980, 138).

Conclusion

Although the story detailed in this article took place in the mid-nineteenth century, it provides inspiration for the twenty-first. Jenny Lind’s incredible singing combined performance at the highest artistic level with a repertory that appealed to the masses. Her international stature as a singer, paired with P. T. Barnum’s expert marketing, led to a concert tour that touched countless lives. Her sense of charity and goodwill, combined with his recognition of charity as a good marketing strategy, benefited countless recipients.32Barnum’s philanthropy evolved in the years beyond the 1850 Jenny Lind tour of America. According to Andrew McClellan (2012, 45), in 1883 “Barnum agreed to build an eponymous museum of natural history on the campus of Tufts University, which he had served as a founding trustee. . . . Barnum hoped to secure a positive legacy through the creation of an unambiguously serious institution. In addition to building and collections [sic] funds, Barnum supplied the Tufts museum—as well as the Smithsonian and American Museum of Natural History in New York—with exotic and valuable dead animals from his circus.”

Today, the arts and philanthropy are closely linked. Arts events are often funded by grants and ticket sales, without profit as a primary goal. Arts organizations must generate enough money to pay their personnel, sometimes well, but their primary aim is artistic rather than monetary. In the nineteenth century, there was not yet an established tradition of nonprofit organizations. Social and humanitarian causes received rightful attention from America’s early philanthropists, such as wealthy businessmen like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller.33In his book Democracy in America (1835), Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59) marveled that Americans voluntary joined together to undertake initiatives that in Europe were performed by aristocrats. By the late 1800s, highly successful American businessmen considered how best to use their wealth. Andrew Carnegie advocated donation of surplus money to social causes, and John D. Rockefeller to human welfare. See Pruszewicz and Vander Hulst, (n.d.). Barnum left an estate valued at $10,000,000 ($280,000,000 in 2019) to twenty-seven heirs and charitable bequests, including The Children’s Aid Society (see Cook 2005, 234). The extension of philanthropy both to and from the arts was advanced significantly by Barnum’s marketing of Lind. In the twenty-first century, most presenters seek sponsors and thank them publicly for donations that make events possible. Conversely, concerts are often sought out as a means of fund raising to benefit social causes.

Siting of performances has always ranked high among the considerations of musical artists. In Jenny Lind’s time, while Europe provided glorious opera houses and concert halls, there was nothing comparable in the US. Thus, Lind performed in whatever places were available on the tour Barnum arranged, many of them quite humble. His task was to find venues and then to attract people to attend. Today, the US abounds in multipurpose venues that appeal to a wide range of audiences. Large cities have created some of the best concert halls in the world—witness New York’s Lincoln Center. Small towns eagerly provide arts venues in such settings as schools, churches, sports arenas, and made-over barns. Even when no special sites are available and presenters must improvise venues, performances therein provide artistic and economic benefits to their communities.34Alan Brown (2012) provides a thorough analysis of the role that venues play in arts participation.

Jenny Lind was the first famous European performing artist to travel to the US. Americans had never before heard music of this quality. Thanks to P. T. Barnum, high art became available and attractive. Today, ease of travel for artists as well as for audiences make concert tours by world-famous performers commonplace. Entire orchestras pack up their instruments, equipment, and players and send them via truck or airplane to distant locations where thousands of audience members easily buy tickets online or at the door. Radio, television, recording technology, and the internet have all made access to the world’s best music available at the touch of a button or click of a mouse. Movie theaters offer spectacular showings of entire operas, including backstage operations. Arts management companies guide the careers of hundreds of performers. Universities offer degrees and certificates in Arts Administration.35Academic programs are described in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arts_administration. A google search for “arts management” reveals a long list of universities offering degrees and programs; see https://www.google.com/search?q=arts+management. Courses in Arts Management include the history of its development as a professional field, beginning with the 1850 American tour of Jenny Lind managed by P. T. Barnum.36I thank Natalie Neuert, Director of the Lane Series and teacher of a course entitled “Arts Management: Presenting the Performing Arts” at the University of Vermont, for her syllabus and insights.

Jenny Lind was a highly talented singer who emerged from humble origins. She came to know the monetary value of musical performance beyond her wildest dreams. P. T. Barnum was a humbugger and successful businessman who came to know the artistic and philanthropic value of music beyond anything he could ever have imagined. The broad popularity of musical performance today owes much to the collaboration of an exceptionally gifted and generous opera singer and an aggressive business entrepreneur with far more interest in money than music—the unlikely alliance of the Swedish Nightingale and the Prince of Humbug.

Notes

1. These images show a portrait signed and dated in Jenny Lind’s handwriting, and the same portrait appearing on the Swedish 50 Kroner bill.

2. Anders Brändström (1999, 94–95) claims that in Sweden from 1811–20, only 6.2 percent of all births were illegitimate, explaining that “[i]n the eyes of the Swedish Protestant church[,] the mother of an illegitimate child was not ‘pure’ . . . [and] was obliged to face the minister and admit her sins.” By contrast, as stated in Statistics Sweden (2015), the Swedish governmental agency responsible for official statistics in that country, “[m]ost of the children In Sweden [as of 2015] are born out of wedlock[,] and this has been the case since 1993. . . In 2013, 54.4 percent of the children were born to an unmarried mother.” In the mid-nineteenth century, divorce was opposed by both church and state. There was statistically only one divorce per 5,000 marriages (Lundh 2003, 11). By comparison, as of 2018, “28 percent of people born to Swedish parents had divorced” (Kauffman 2018, 1).

3. Musical notation of the fanfare appears in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 1:16).

4. This portion of her history is recorded by her eldest son in 1887.

5. Quoted in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 1:49).

6. "Mademoiselle, vous n'avez plus de voix" (Holland and Rockstro 1891, 1:11).

7. Chapter 11 (Method) of Holland and Rockstro explains Lind’s vocal abilities and Garcia’s teaching in detail.

8. Holland and Rockstro (1891, 2:305) present a complete list of Lind’s operatic roles.

9. Another definition of humbug comes from a Wikipedia website (2019): “A humbug is a person or object that behaves in a deceptive or dishonest way, often as a hoax or in jest. The term was first described in 1751 as student slang, and recorded in 1840 as a "nautical phrase. "It is now also often used as an exclamation to mean nonsense or gibberish.”

10. PT Barnum Images-hum bug includes "Hum-Bug," the cartoon by H. L. Stephens (1851).

11. Barnum also says that “I discovered her weak point. It was discovered in seven letters—W-H-I-S-K-E-Y . . . and for a drop of it, I found I could mould her to anything” (Cook 2005, 24).

12. Dollar Inflation Calculator, https://www.officialdata.org. All dollar conversions in this article come from this website.

13. The New York Sun, February 26, 1836, quoted in Cook 2005, 52.

14. “Scudder’s American Museum,” Wikipedia 2019.

15. By the time Tom Thumb reached the age of fourteen, Barnum was paying him $10,400 per year (approximately $350,000 in 2019). See P. T. Barnum (1852).

16. This engraving is housed in the Bridgeport Public Library. Photo and citation are in Kunhardt (1995, 57, 357). The name of Tom Thumb’s handler—in the background—is unknown.

17. The contract also stipulated that if the total promised amount was earned and all expenses paid by the 75th concert, Barnum would then pay her 20% of the ensuing receipts, provided that he had cleared at least ₤15,000 (approximately $2,550,000 in 2019). Further financial details appear in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 2:366–68). See websites listed below for pound to dollar conversion and dollar inflation calculator.

18. Details of the contract and its negotiations appear in Barnum (1927, 318–28) and in Holland and Rockstro (1891, 2:364–69).

19. Photo, Illustrated London News, August 24, 1850.

20. Photo, Ladies Home Journal, November, 1896.

21. According to the Wikipedia website (2019), John Nicholas Genin (1819–78) was so famous for making hats that folks everywhere (especially after the Lind ticket-sale episode) would take off their hats to check whether or not they were wearing "a Genin."

22. Lind writes home to her parents: “We rarely make less than $10,000 [approximately $325,000 in 2019] at a concert. . . . My share for six concerts is $30,000 [$978,000]!” She also recounts that the first ticket was auctioned for $625 ($20,000; see Holland and Rockstro [1891, 2:418–20]). After that first concert, Lind insisted that at least some tickets be made available for ordinary audience members (without auction) at $1 and $2 ($33 and $66). See Jenny Lind Tour 2019.

23. Barnum (1927, 334) includes the complete poem.

24. Greetings to America; text by Bayard Taylor, composed by Julius Benedict (Parcells, 1989).

25. In today’s music world, concerts successfully combine high art with popular styles, which was unusual in Jenny Lind’s time. Alex Ross discusses “Popular Music” versus “Classical Music . . . by Implication, Unpopular Music” in an engaging article in the New Yorker (2004, 3).

26. Maude (1926, 160–61) explains that “the famous ‘Echo Song’ is a Norwegian melody, and the “Herdman’s Song” was written by Mlle. Lind’s singing master, Berg. Both of them were constantly sung by Mlle. Lind. Mr. Barnum . . . probably, at that date[,] did not know the difference, and Mlle. Lind is not likely to have seen the proofs of the programme.”

27. The score of Berg’s Herdsman’s Song is included in Holland and Rockstro (1891, Appendix, 19–20).

28. This trio was written especially for Lind. The opera is a Singspiel with a somewhat historical plot featuring the flute-playing King Frederick the Great of Prussia (for whom J. S. Bach composed The Musical Offering). The plot involves the king trying to escape from Hungarian soldiers in Silesia (now southern Poland). A clever switch of the flute-playing character Conrad for the flute-playing king helps him escape. As a reward, Conrad is granted permission to marry the girl he loves, Vielka the gypsy. The trio in the last act features the King and Conrad, flutists, and Vielka the gypsy, a soprano.

29. Barnum quotes the Havana correspondence from the New York Tribune, but does not include the date.

30. To my knowledge, there is no score nor recording of “Greetings to America.” Apparently it was never published. Its words appear in Ware (1980, 134,) quoting the New York Tribune, May 27, 1852.

31. Lind especially channeled her donations toward endowments for free schools in Sweden. Scholarships funded by her endowments are administered to this day by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music (Jenny Lind, Wikipedia 2019).

32. Barnum’s philanthropy evolved in the years beyond the 1850 Jenny Lind tour of America. According to Andrew McClellan (2012, 45), in 1883 “Barnum agreed to build an eponymous museum of natural history on the campus of Tufts University, which he had served as a founding trustee. . . . Barnum hoped to secure a positive legacy through the creation of an unambiguously serious institution. In addition to building and collections [sic] funds, Barnum supplied the Tufts museum—as well as the Smithsonian and American Museum of Natural History in New York—with exotic and valuable dead animals from his circus.”

33. In his book Democracy in America (1835), Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59) marveled that Americans voluntary joined together to undertake initiatives that in Europe were performed by aristocrats. By the late 1800s, highly successful American businessmen considered how best to use their wealth. Andrew Carnegie advocated donation of surplus money to social causes, and John D. Rockefeller to human welfare. See Pruszewicz and Vander Hulst, (n.d.). Barnum left an estate valued at $10,000,000 ($280,000,000 in 2019) to twenty-seven heirs and charitable bequests, including The Children’s Aid Society (see Cook 2005, 234).

34. Alan Brown (2012) provides a thorough analysis of the role that venues play in arts participation.

35. Academic programs are described in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arts_administration. A google search for “arts management” reveals a long list of universities offering degrees and programs; see https://www.google.com/search?q=arts+management.

36. I thank Natalie Neuert, Director of the Lane Series and teacher of a course entitled “Arts Management: Presenting the Performing Arts” at the University of Vermont, for her syllabus and insights.

References

Adams, Bluford. 1997. “E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture.” University of Minnesota Press.

Barnum, P. T. 1927. Struggles and Triumphs: or, The Life of P. T. Barnum, Written by Himself. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Brändström, Anders. 1999. Illegitimacy and Lone-Parenthood in XIXth Century Sweden. Annales de Démographie Historique 1998-2.

Brown, Alan. 2012. “All the World’s a Stage: Venues and Settings, and the Role They Play in Shaping Patterns of Arts Participation.” Grantmakers in the Arts Reader 23, no.2. https://www.giarts.org/article/all-worlds-stage.

Brown, Stephen, and Christopher Hackley. 2012. “The Greatest Showman on Earth: Is Simon Cowell P. T. Barnum Reborn?” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 4, no. 2.

Cook, James W., ed. 2005. The Colossal P. T. Barnum Reader. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Harris, Neil. 1973. Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Holland, Henry Scott, and W. S. Rockstro. 1891. Memoir of Madame Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt. 2 vols. London: John Murray. This is the official biography written soon after Jenny Lind’s death, with primary materials gathered by her husband.

Kauffman, Ronald H. 2018. “Sweden’s High Divorce Rate.” https://www.rhkauffman.com/swedens-high-divorce-rate/.

Kunhardt, Philip B. Jr., Philip B. Kunhardt III, and Peter W. Kunhardt. 1995. P. T. Barnum, America’s Greatest Showman. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Lundh, Christer. 2003. “Swedish Marriages: Customs, Legislation and Demography in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” Lund Papers in Economic History, no. 88. Lund, Sweden: Lund University, Department of Economic History.

Mansky, Jackie. 2017. “P.T. Barnum Isn’t the Hero the “Greatest Showman” Wants You to Think.” Smithsonian.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-pt-barnum-greatest-humbug-them-all.

Maude, Mrs. Raymond, O.B.E. 1926. The Life of Jenny Lind. London: Cassell and Company, Ltd. This biography was written by Jenny Lind’s daughter and published on the fiftieth anniversary of Lind’s death.

McClellan, Andrew. 2012. “P. T. Barnum, Jumbo the Elephant, and the Barnum Museum of Natural History at Tufts University.” Journal of the History of Collections 24, no. 1: 45–62.

McCullough, David. 2011. The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Pleasants, Henry. 1966. The Great Singers. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ross, Alex. 2004. “Listen To This: A Classical Kid Learns to Love Pop—and Wonders Why He Has to Make a Choice.” https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2004/02/16/listen-to-this.

Shultz, Gladys Denny. 1962. Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. This biography was written a half-century after Lind’s death and draws on documents made available after the deaths of all the principal persons in her life.

Suess, Jeff. 2018. “Our History: ‘Greatest Showman’ Barnum and Singer Lind Put on Show for the Ages.” Cincinnati.com/The Enquirer, January 10, 2018. https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2018/01/10/our-history-greatest-showman-barnum-and-singer-lind-put-show-ages/999666001/.

Ware, W. Porter, and Thaddeus C. Lockard. 1980. P. T. Barnum Presents Jenny Lind. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Websites

“Arts Administration.” Wikipedia. 2019. Last modified March, 15, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arts_administration.

“Arts Management.” 2019. Google Search. https://www.google.com/search?q=arts+management.

Dollar Inflation Calculator. 2019. https://www.officialdata.org. This website calculates U.S. dollar equivalents from a given year to another.

“Genin the Hatter.” Wikipedia. 2019. Last modified February 20, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Nicholas_Genin.

“Humbug.” Wikipedia. 2019. Last modified June 7, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humbug.

“Jenny Lind.” Wikipedia. 2019. Last modified June 11, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jenny_Lind. Biography of Jenny Lind.

Jenny Lind Images. Google. 2019. https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=jenny+lind+images. Images from various sources, cited within the website.

“Jenny Lind Tour.” Wikipedia. 2019. Last modified May 29, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jenny_Lind_tour_of_America,_1850.

“Niblo’s Garden.” Wikipedia. 2019. Last modified April 3, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niblo's_Garden.

Pound to Dollar Conversion. 1995–2019. https://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/convert/.

Pruszewicz, Aleksandra and Angela Vander Hulst. n.d. “Key Dates and Events in American Philanthropic History 1815 to Present.” Learning to Give. Accessed June 24, 2019. https://www.learningtogive.org/resources/key-dates-and-events-american-philanthropic-history-1815-present.

PT Barnum Images. Google 2019. https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=pt+barnum+images. Images from various sources, cited within the website.

“P. T. Barnum Made Tom Thumb Wealthy.” 1852. Union Democrat, Manchester, New Hampshire, September 7, 1852. http://www.rarenewspapers.com/view/606783.

“P. T. Barnum.” Wikipedia. 2019. Last modified June 22, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P._T._Barnum. Biography of P.T. Barnum.

“Scudder’s American Museum.” Wikipedia. 2017. Last modified July 29, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scudder%27s_American_Museum.

Statistics Sweden. 2015. “Marriages and Births in Sweden.” https://www.scb.se/en_/Finding-statistics/Articles/Marriage-now-more-common-in-Sweden/. See also Eurostat Statistics Explained. 2018. Archive: “Marriages and Births in Sweden.” Last modified July 26, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Archive:Marriages_and_births_in_Sweden&oldid=396647 (cached).

Recordings

Parcells, Elizabeth. 1989. A Jenny Lind Recital. Classical Arts NR 237-CD. Copyright holder cannot be found. Northeastern Records purchased the rights to the Classical Arts catalog in 1988. The rights were then sold to Seesaw Music Corporation, which was then acquired by Subito Music Corporation, at unknown dates. The author’s attempt to reach Subito Music via http://www.subitomusic.com/contact-us/ produced no answer.

Söderström, Elisabeth. n.d. Elisabeth Söderström Sings Swedish Songs. Swedish Society Discofil SCD 1017. Permission granted by Naxos Sweden.

Sutherland, Joan. 2008. “Joan Sutherland: Meyerbeer Trio 2 Flutes and Soprano.” L’etoile du nord – “C’est bien lui.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Te_VL1e5s_U.