Abstract

Since student composers with non-classical backgrounds are more common than ever in college music programs, creating new strategies for teaching them concepts of form and structure presents a challenge for the composition teacher. The use of model composition in which students are encouraged to employ classical forms such as sonata or rondo in their studies is only useful for those students already familiar with them. In order to best serve those students who lack this background, better models for such formal approaches need to be devised. In this article, I argue that all students, regardless of background, already possess models for formal and structural expression: stories. The article provides an overview of the issues and concerns surrounding modern compositional pedagogy, then outlines an approach to teaching composition using narrative designs to model concepts of form, structure, and development. It considers the monomyth and the Freytag pyramid—narrative frameworks shown to guide storytelling traditions across the world—and shows their close relationship with traditional paradigms of musical form. Using a combination of musical analysis, narrative analysis, and case study, I propose a pedagogy for composition that uses these narrative designs as models for musical structure. I not only demonstrate how this strategy can be used to teach structural concepts of composition to students who may be encountering the concert music world for the first time but also explore its potential for guiding every kind of student in the increasingly diverse composition studio of today.

The Goals of Teaching Composition

When I discuss pedagogy with my colleagues in performance, theory, or musicology, I am often reminded of the extent to which what happens inside the composition studio is a mystery to those outside of it. Although composition is usually classified as an applied study, like clarinet or cello or voice performance, teaching strategies are much less defined because composition study lacks the clear goals of other applied areas. Most applied teachers can identify a set of benchmarks for student mastery that are largely agreed upon by the field at large. For example, violin teachers would likely agree that every undergraduate performance major should finish their degree by learning at least one Bach partita. However, to the best of my knowledge, no such consensus exists on what the educational benchmarks should be for an undergraduate composition major. At some point in recent history, there may have been a consensus that all composition majors should write an orchestral work and/or study post-tonal compositional practice, but that is rapidly breaking down as technology gains prominence in the curriculum and ensures greater access to more eclectic genres and styles.

Should a composition degree invariably lead to expertise in writing in the European classical music tradition, even for students who aspire to be electronic musicians, film and media composers, or pop musicians? Are these students’ creative energies better spent pursuing other competencies during their four (and often fewer) years of applied composition study? In this changing musical world, is the inverse true: Should all students be expected to showcase mastery of technology or popular traditions, even at the expense of more classically focused training?

There are no easy answers to these questions, and the result is a field in which even composition pedagogues seldom agree on the teacher’s role and responsibilities. Agreement or not, all composition pedagogues wrestle with contradictions in their teaching practice. The composer-teacher is constantly wary of imprinting his or her own compositional style on a student, yet is obligated to help a student develop a sense of aesthetic quality. While the composer-teacher understands the importance of the masterwork tradition in informing creative choices, he or she may also be aware that more and more frequently, students come to the composition studio with musical passions and experiences that may have little connection with the classical music canon, long seen as the primary source of models for musical greatness. Ultimately, each pedagogue resolves these contradictions in individual ways, resulting in separate successes and failures. And in such a fractured environment, even defining the goals of composition pedagogy can become a challenge.

Despite this difficulty, establishing clear goals is an indispensable precursor to any meaningful discussion of teaching methods. In my composition pedagogy, I have two prominent goals: (1) to help a student express most effectively those things he or she is hoping to communicate musically (that is, their compositional intention), and (2) to help a student develop strategies for creating new material that can aid him or her in overcoming writer’s block.

Model Composition and Its Limitations

An extremely useful and common teaching strategy for achieving these goals is model composition: assigning the student to use or interpret classical formal types, such as sonata or five-part rondo form, in their composing. Model composition absolves the student of the need to tackle form as an expressive consideration, since the structure is predetermined at the outset of the project. Instead, students can use form to guide the large-scale narrative of their compositions, alleviating the creative paralysis of writer’s block. Furthermore, reliance on model frameworks removes form as an intimidating compositional variable, leading the student to focus on other musical elements, such as melody and harmony. The pedagogue can then focus the student’s attention on his or her use of these elements in relation to compositional intention. Because it highlights these basic elements, model composition can be especially valuable for students who are musically literate but inexperienced composers.

In addition to being a foundational part of the pedagogy advocated by Arnold Schoenberg, one of the most influential composer-teachers of the last century, model composition is used in the theory classroom, particularly to teach complex formal designs such as sonata form.1Sabine Feisst, Schoenberg’s New World: The American Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 225. Sylvia Parker, writing in the Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy, observed that a model composition assignment designed to teach sonata form as part of a theory class was not only effective but also engendered in her students a greater enthusiasm for creative composition.2Sylvia Parker, “Understanding Sonata Form through Model Composition,” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 20 (2006): 135. Michael Searby, writing in the same journal, noted that this modeling technique is frequently utilized in important composition pedagogy methods of the twentieth century, including those outlined by Reginald Smith Brindle and Margaret Lucy Wilkins.3Michael Searby, “‘Composers Are Born and Not Made’: Some Preliminary Thoughts On How To Construct A Pedagogy For Music Composition,” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 31 (2017): 254.

The pedagogical principles of modeling remain useful: it can provide frameworks upon which the student can build creatively, thus reducing the number of musical problems to be solved and allowing greater focus on developing the two competencies outlined above. However, models drawn solely from classical music may not be adequate tools for teaching a more diverse student body.

As more musicians from non-Western Art music backgrounds enter music programs, a student’s existing familiarity with classical music and its formal conventions is less assured. In addition, it becomes more likely that students will enter the composition program with little more than an intuitive understanding of basic music theory. These students may not be prepared, moreover, to model classical formal structures in their composing until they have completed several semesters of music theory study. Accordingly, if a composition teacher has no other tools for discussing musical structure and its dramatic arc, that represents a quarter of the student’s education (or more) spent without discussing such a concept, one of the most important elements of composition study.

New teaching tools are needed, such as ways of presenting compositional concepts and linking them with: (1) students who may come from diverse backgrounds that evince little or no connection with the institution in which they are enrolled, (2) the European classical music tradition that such an institution embraces, or even (3) the composition teacher with whom they study. In this article, I argue that the best new models for helping today’s young composers achieve their musical and creative goals can be found in one of humanity’s oldest and most universal of art forms: storytelling.

Music as Narrative

To begin, I propose a simple—yet deceptively complex—idea: music, in all its forms, is a type of storytelling. This is not to say that music is always programmatic, or that it otherwise follows the rules we traditionally assign to literary narrative. Indeed, to suggest those things would be obtusely reductive to both music and the idea of narrative itself. Rather, the idea begins in an understanding that storytelling is universal, and its presentations are myriad. In “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative,” Roland Barthes writes: “There are countless forms of narrative in the world . . . . [A]mong the vehicles of narrative are articulated language, whether oral or written, pictures, still or moving, gestures, and an ordered mixture of all those substances. . . . [I]n this infinite variety of forms, it is present at all times, in all places, in all societies. . . .”4Roland Barthes, “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative,” trans. Lionel Duisit, New Literary History 6, no. 2, On Narrative and Narratives (Winter 1975): 237.

This universalist approach to narrative widens the focus of the concept to include any form of expression that follows the criteria Barthes delineates in the remainder of his essay. The inroads for examination that Barthes offers are many (and examination of how his comprehensive theory might guide musical thought deserves its own essay); but a litany of them depends on the evolution of the viewer/listener/reader’s understanding of the work over time, whether that time lasts the duration of a sentence, a chapter, or an act of a play.

Following Barthes, I argue that narrative includes (but may not be limited to) any expression that is experienced over time. By definition, this includes music, which relies (regardless of its parent culture) on the evolution of a listener’s understanding over the temporal course of a performance or recording. Music, then, is a type of narrative—a type of storytelling—and at its core, the study of composition is the study of using music to construct a narrative. Therefore, structural designs that guide our collective understanding of narrative, literary or otherwise, can be useful in teaching student composers.5The intimacy of this relationship between music and narrative need not be taken at face value. Indeed, existing structural models for musical forms bear deep-seated resemblances to several structural narrative forms.

Perhaps the most well-known structuralist paradigm for understanding narrative is the monomyth, also known as the “Hero’s Journey.” While the monomyth has existed in some form for centuries, it was popularized in the mid-twentieth century by Joseph Campbell in his landmark 1949 text, The Hero With a Thousand Faces.6Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces, 3rd ed. (Novato, CA: New World Library, 2008). Campbell observes that myths and legends from cultures around the globe often conform to a common narrative design that follows a protagonist (the “Hero”) from the earthly realm into a supernatural realm, where they complete a quest before returning home, having successfully mastered the supernatural.

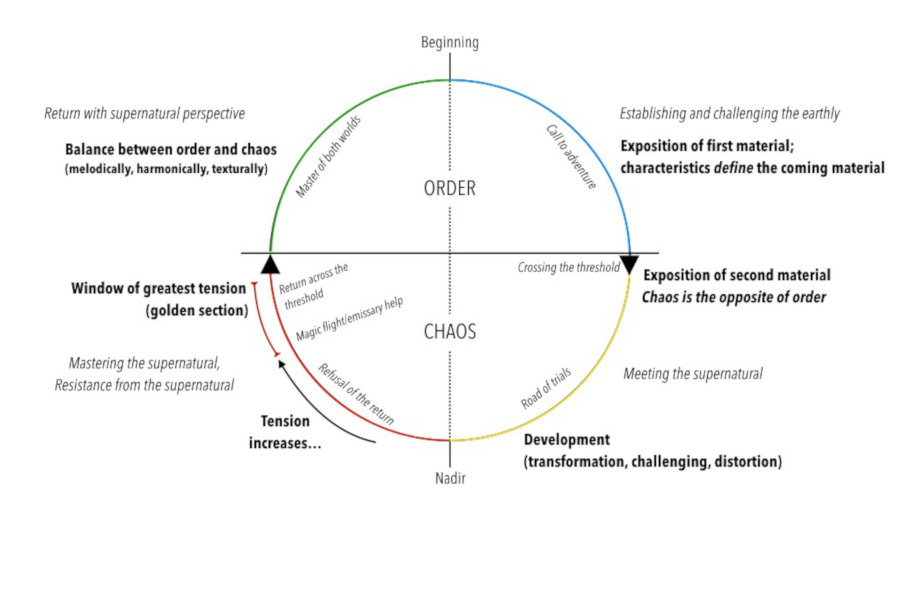

Various manifestations of the monomyth include between twelve and seventeen discrete “stations” that are shared by the myths of countless civilizations. For the purposes of this article, I have condensed them to nine. As will be shown later, the Hero’s journey is an extremely useful inroad to understanding narrative in all its forms, including musical. The ability of the monomyth to elucidate musical forms is a particularly powerful tool for the pedagogue, as it offers students with limited music theory training access to concepts of musical structure and contrast. In doing so, the individual stations of the protagonist are of secondary importance to the evolving relationship between the earthly realm, or “order,” and the supernatural realm, or “chaos”; however, both are addressed here.

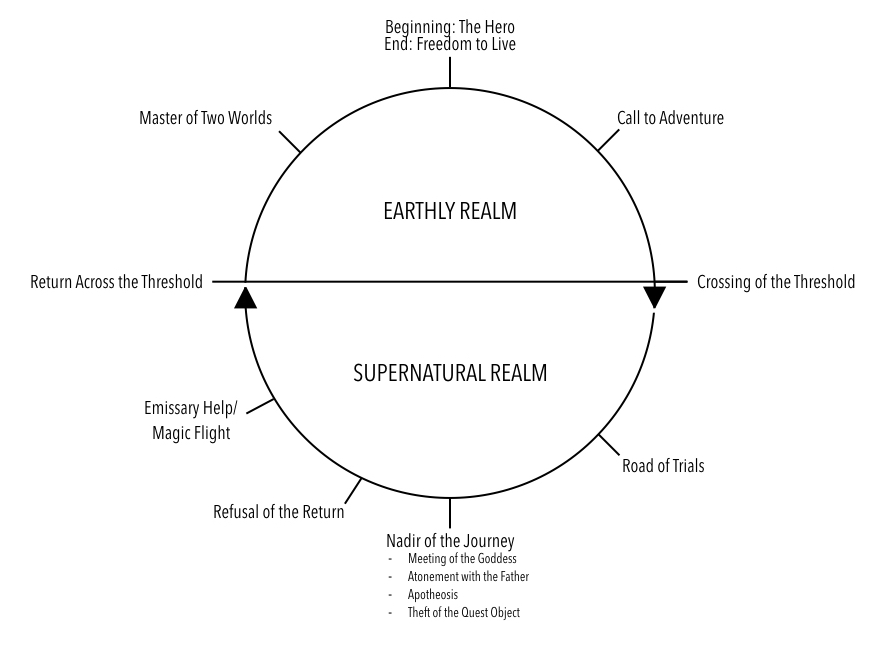

Figure 1: The monomyth and its nine stations

Figure 1 shows a nine-station version of the monomyth. The circular presentation is typical, illustrating the Hero’s journey, beginning at home and successfully returning at the end of the story. The nine stages can be summarized as follows:

Call to Adventure. The Hero begins a journey in the earthly realm, deciding to take action due to some disturbance or disruption in his or her surroundings. The disturbance inspires the Hero to venture into unknown territory.

Crossing of the Threshold. The Hero’s destination lies in the supernatural realm. Although in many stories the realm is quite literally supernatural, it more generally represents the unknown or unfamiliar. The crossing of the threshold is usually treacherous, and safe crossing requires that the hero (and, by extension, the reader) transcend his or her earthly perceptions of reality.

Road of Trials. Venturing through the supernatural realm, the Hero encounters a series of obstacles in which perceptions of reality are further challenged. In addition to representing “trial by fire” for the Hero, the Road of Trials breaks down the rules and preconceptions associated with the earthly realm, establishing the supernatural as an opposing, “chaotic” entity.

The Nadir of the Journey. The Nadir is the deepest point in the supernatural realm, the point of furthest removal from the Hero’s initial understanding of reality. The paradigms listed in Figure 1 (Meeting of the Goddess, Atonement with the Father, Apotheosis, Theft of the Quest Object) are different forms this moment can take. Whatever its form, the Nadir represents the moment in which the Hero must (and does) achieve mastery of the supernatural in order to continue.

Refusal of the Return. The Hero resists destiny in order to leave the supernatural and return to the earthly realm with newfound knowledge. Some myths end at this station; rather than return, the Hero is consumed by his or her mastery of the supernatural and chooses to stay.

Emissary Help/Magic Flight. After refusing to return, outside forces must coax the Hero into completing the journey. This sometimes takes the form of an emissary from the earthly realm reaching out to the Hero across the threshold (Emissary Help), and sometimes involves the Hero’s allies in the supernatural realm offering aid (Magic Flight).

Return Across the Threshold. As the supernatural and earthly both seek to claim the Hero as their own, the return creates a climactic struggle between the two realms. The period between the flight and this threshold crossing is the period of greatest tension in the story, and the Hero’s successful crossing usually comes only at a great sacrifice, on the part of the Hero or others.

Master of Two Worlds. The Hero’s successful return to the earthly realm grants the protagonist, in Campbell’s words, the “freedom to pass back and forth across the world division.7Campbell, The Hero, 196.” The Hero is now endowed with the knowledge to understand both the earthly and the supernatural realms, and the two forces are in balance with one another, resolving the conflict of the story (Freedom to Live).

The monomyth is easily interpreted as the story of a protagonist who is inspired, challenged, and ultimately victorious, in other words, a Hero’s Journey. However, Campbell’s interpretation of the monomyth grew from a deeper level of meaning. He observed that the legends which followed the monomythic design were usually outgrowths of their parent culture’s rites of passage, which themselves were meant to “conduct people across those difficult thresholds of transformation that demand a change in the patterns not only of conscious but also of unconscious life.”8Campbell, 6. In Campbell’s view, the Hero is a vehicle for the exploration of two states— the pre-transformation earthly realm and the post-transformation supernatural realm—and ultimately, integration of new knowledge into one’s understanding. In turn, the monomyth can be understood as the story not of the Hero, but of a conflict between two competing states, the earthly realm (Order) and the supernatural realm (Chaos).

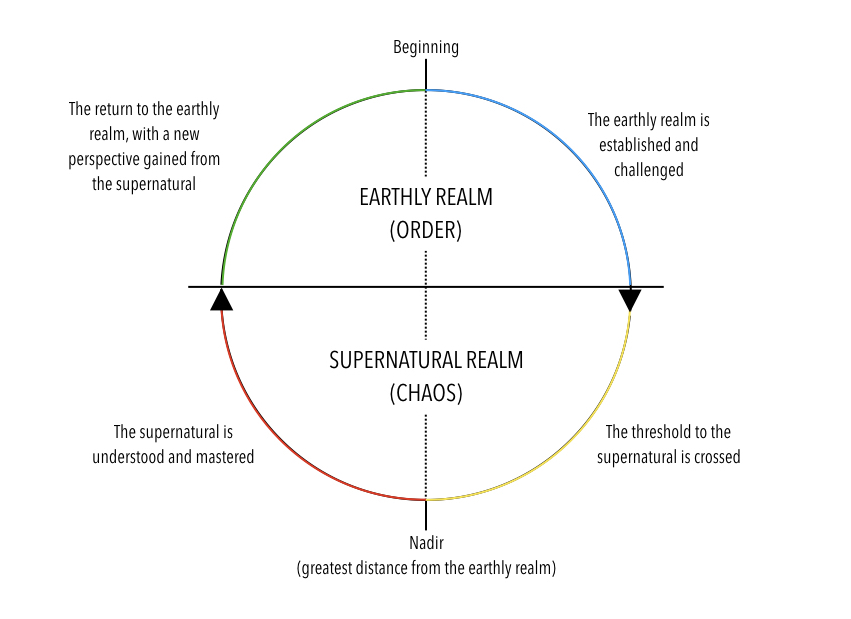

Figure 2 distills the stations of the monomyth to four quadrants, each representing a different level of balance between Order and Chaos (interpreted here to not be literally chaotic, but an opposing state to Order). Once Order is established, it is challenged by Chaos, which is then

Figure 2: A four-quadrant distillation of the monomyth

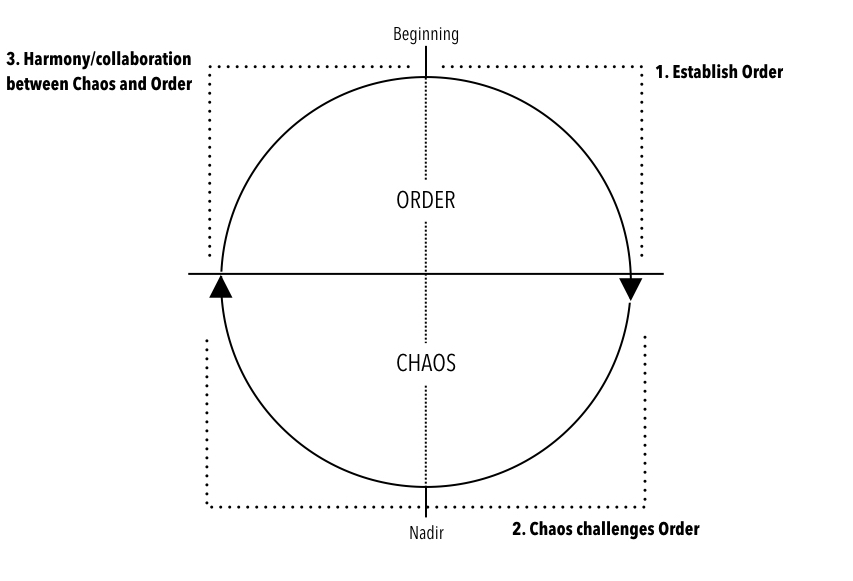

explored and eventually mastered, culminating in a climactic return across the threshold. The story ends with a restored balance between the two forces, resulting from knowledge and mastery of both. Distilled further, the monomyth can be presented simply as a three-part exploration of two forces, Order and Chaos (Figure 3):

Figure 3: Three-part distillation of the monomyth

At its core, the monomyth is an aid to understanding literary structure and how various dramatic forces affect the story’s reader/listener. Similar aids abound in music, and many of them serve as pedagogical tools for student composers, one of which is sonata form. Virtually all American music students are required to study sonata form as part of their undergraduate curriculum, and as discussed earlier, it continues to function as a core component of a model-based composition approach to teaching aspiring composers.

While the study of sonata form typically revolves around harmonic and thematic elements— which are certainly essential to understanding the form itself—many of the prominent approaches to understanding this form create meaningful space for its significance as a dramatic structure. This includes the work of Charles Rosen. Author of Sonata Forms, Rosen was an influential proponent of a “sonata principle” as a means to grasp how sonata forms work.9Charles Rosen, Sonata Forms, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1988). Rosen begins from an understanding of the sonata as a form that derives its efficacy from the tension between tonic and non-tonic key areas, and the long-term effort to resolve this tension by restating all material in the tonic key. As Rosen states, “[S]onata forms . . . [provided] an equivalent for dramatic action, and [conferred] on the contour of this action a clear definition. The sonata has an identifiable climax, a point of maximum tension to which the first part of the work leads and which is symmetrically resolved.”10Rosen, 9–10.

This dramatic consideration is also present in the work of James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy.11James A. Hepokoski and Warren Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). In Elements of Sonata Theory, Hepokoski and Darcy propose a dynamic, flexible approach to sonata analysis, fluid by design in order to accommodate the shifting cultural norms surrounding musical form in various historical periods. Unlike Rosen’s structural approach to sonata form, Hepokoski and Darcy encourage a narrative one instead:

A sonata dramatizes a purely musical plot that has a beginning (P, the place from where it sets out with a specific tonal-rhetorical aim in mind), a middle (including a set of diverse musical adventures), and a generic conclusion of resolution and confirmation (the ESC [essential structural closure, a moment of significant cadence in the recapitulation] and subsequent music). It is in the nature of the sonata to set up a quest narrative. In addition to being required to display (or at least refer to) the interior, multitextured norms of sonata practice, a sonata must realize those norms coherently, in such a way as to move toward and secure the ESC and generic closure.12Hepokoski and Darcy, 251.

In the work of both Rosen and Hepokoski and Darcy, then, narrative is used to point to a sonata’s “motivations” and the tension derived from presenting (and overcoming) obstacles to those motivations. It would be easy enough to draw broad-brush parallels between these paradigms and monomythic structure, especially given the “three-act” understanding of sonata form (exposition, development, and recapitulation) that remains constant between both approaches. However, a closer comparison will reveal the extent to which sonata form and the monomyth mirror each other’s smaller-scale dramatic motions. It will also show, by extension, the monomyth’s usefulness for young composers who may not yet understand sonata form, but possess a deep familiarity with dramatic structure.

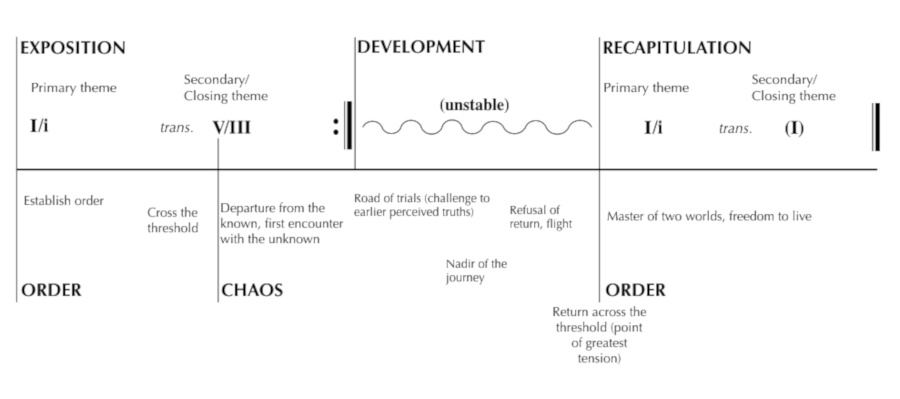

Figure 4: Comparing sonata form with the monomyth

Figure 4 shows a diagram of the basic structural elements of sonata form, including its formal sections and the harmonic and thematic characteristics of each. Below the center line is a horizontal representation of the monomyth, including both the motion across the threshold to Chaos and the final return to Order. Several stations of the monomyth are also shown.

In comparing sonata form with the monomyth, several immediate connections emerge. As with the monomyth, sonata form is an exploration of a low-tension, familiar “Order” force (tonic) and a higher-tension “Chaotic” force (non-tonic, including both the dominant and the harmonic instability of the development). Crossing the threshold to the non-tonic areas of the form brings with it first encounters with alien characters endemic to the Chaotic realm: the secondary and closing themes. All materials are harmonically and melodically distended in the development, and this peak of unfamiliarity geographically coincides with the Nadir of the journey, the point furthest from the initial stability of Order. Significantly, Hepokoski and Darcy identify the development as an area that defies the sonata principle, an area in which new thematic ideas are “[not] under any obligation to be resolved in the tonic later in the movement.”13Hepokoski and Darcy, 243. The existence in this area of musical forces totally unfamiliar to the areas associated with Order further solidifies the significance of the Nadir as a component of the sonata’s dramatic structure.

Tension increases near the end of the development in a sonata form, as the retransition creates anticipation of the return to the tonic. This state of affairs is mirrored in the monomyth, as the Hero is torn between Order and Chaos. As the tension increases toward the climactic return of the tonic, the threshold to Order is once again crossed, in the monomyth as well as in the sonata form. Accordingly, the forces of Order and Chaos begin moving into balance. The Hero has become the Master of Both Worlds, as the sonata restates all melodic material, including the Chaotic second and closing theme, in the tonic, the key of Order. For both forms, the journey ends with a harmonious resolution of the story’s tension.

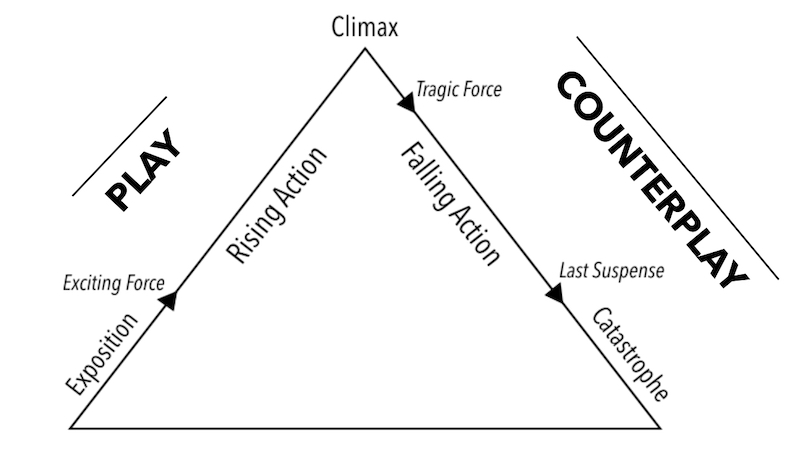

While the monomyth has been an influential model for creation (and interpretation) within filmic and literary traditions, other structuralist designs have taken on similar significance for the modern understanding and creation of narrative.14For examples of such filmic and literary traditions, see, respectively, Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 3rd ed. (Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007), 3; and Steven R. Phillips, “The Monomyth and Literary Criticism,” College Literature 2, no. 1 (Winter 1975): 1–16. One prominent example is Gustav Freytag’s five-part pyramidal structure for understanding drama, commonly known as “Freytag’s pyramid” (Figure 5).15Gustav Freytag, Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art, trans. Elias J. MacEwan (Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Co., 1894), 115. As was the case for the monomyth, the patterns that this structure highlights also underscore the dramatic action in historically significant musical forms, which themselves are useful as model compositions. Of particular note here is the structural balance of the dualist forces of “play” and “counterplay,” although I will begin by discussing Freytag’s five-part design and its implications.

Figure 5: Freytag’s pyramid of dramatic action (not to scale)

Freytag’s dramatic structure divides the narrative into “five parts and three crises.” 16Freytag, 106. Following the exposition, the first “crisis,” the exciting force, spurs the protagonist to action (similar to the call to adventure in the monomyth). This marks the beginning of the rising action, during which the protagonist makes decisions that have unforeseeable effects on the surroundings and the other characters. Following the climax, the rising action is replaced by a falling action in which the protagonist witnesses the consequences of the decisions he or she made in the previous half of the drama. Often this is spurred by a tragic force (the second “crisis”), which marks the moment the protagonist’s fortunes begin to turn sour. The falling action and its consequences usually mean that a tragic end is preordained for the protagonist. Despite a last suspense (the third “crisis”) that may, for a time, suggest that a different path is possible, the action inevitably leads to catastrophe. Upon arrival at the Catastrophe, the final consequences of the rising action are revealed, and (in the case of dramas) usually spell a tragic end for the protagonist.

As was the case with the monomyth, this lower level of organization in Freytag’s pyramid exists to serve a larger balance within the narrative form, between what Freytag identifies as “states of the action.” 17Zach Tomaszewski, “Marlinspike: An Interactive Drama System” (PhD diss., University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2011), 31. At any given moment, the story is either in a state of “play” or “counterplay.” During “play,” the protagonist acts on his or her surroundings proactively, evoking responses and consequences as a result. “Counterplay” represents the inverse: the protagonist is acted upon by the environment, adversaries, or the consequences stemming from his or her choices earlier in the drama.

While play and counterplay are both essential parts of dramatic form, they are not necessarily sequential: a drama can feature a counterplay succeeded by a play. The primary distinction here is whether or not the protagonist is either the initiator or the recipient/respondent of the action. In either case, the climax represents the transition from one state to another. In other words, either the protagonist is brought to bear the consequences of his earlier actions (play-counterplay) or the protagonist is motivated to actively engage with and direct the action of the drama (counterplay-play). The Freytag pyramid model of dramatic action, then, can be distilled to a binary study of actions, and the consequences of those actions.

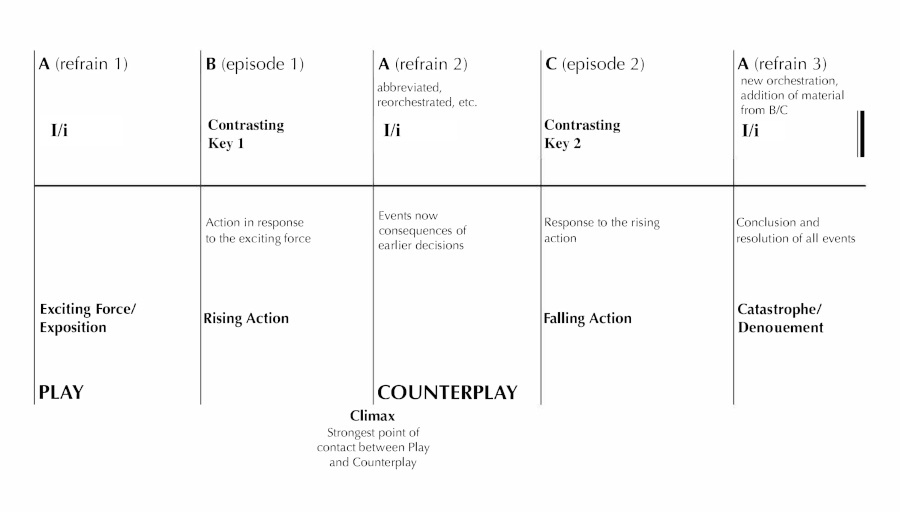

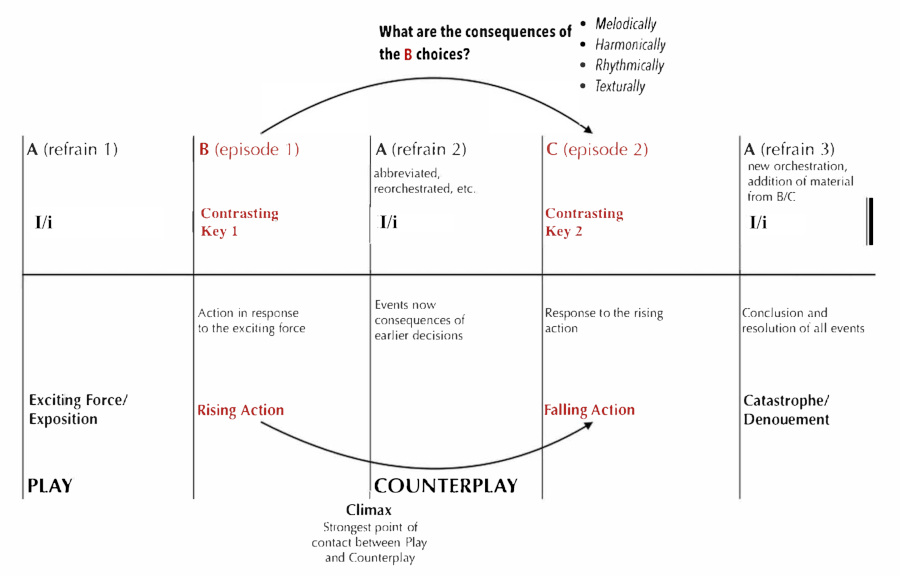

Within the boundless musical forms that reflect the Freytag pyramid’s symmetry, the complexities of the interaction between play and counterplay are cleanly mirrored in a five-part rondo form (Figure 6). While the most recognizable hallmark of this form is certainly the recurring A section (mirrored in Freytag’s three crises, that is, the exciting force, tragic force, and last suspense), equally important is the form’s internal balance between its introduction and transformation of material.

Figure 6: Five-part rondo and Freytag’s pyramid

Following the initial refrain and episode—the A and B sections, a rondo form traditionally bases all subsequent musical decisions on those already made. The A material is revisited and transformed, in a manner defined by the attributes of the first refrain. When the second episode—the C section—occurs, its key, character, and orchestration (if applicable) are perceived in relation to those of the first episode (the B section). This relationship between the episodes, where the characteristics of one are ordained by the other, is mirrored in the Rising and Falling Actions of Freytag’s Pyramid, the clearest manifestations of the relationship between Play and Counterplay. A final statement of the A material acts as catastrophe and last suspense, with any additional material (such as a coda) derived from material already stated in the refrain and/or episodes. Thus, the rondo form’s finale also concludes the story’s actions and consequences, their relationships, in a word, fully realized.

Narrative in the Composition Studio

If the objective of models such as sonata and rondo form is to provide the composer with tools for managing dramatic tension (and its resolution) over the course of a composition, then an understanding of how that tension exists in literary narratives can be useful for student composers, especially those who do not yet possess the skills to interpret these musical forms. Whatever the student’s level of experience with music theory is upon entering an undergraduate music program, it is all but assured that he or she has an intimate understanding of narrative. In “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality,” Hayden White called the impulse to narrate “natural” and added that “far from being one code among many that a culture may utilize for endowing experience with meaning, narrative is a metacode, a human universal on the basis of which transcultural messages about the nature of a shared reality can be transmitted.”18Hayden White, “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality,” Critical Inquiry 7, no. 1, On Narrative (Autumn 1980): 5, 6.

White’s observations about the human instinct for narrative communication and understanding are not merely philosophical, but exhibited in human behavior. Examinations of how children use narrative have suggested that it is a valuable tool for helping them understand their culture and environment. More important, the understanding of narrative and its value can precede a child’s development of the ability to read or write. In fact, narrative abilities play an important role in helping children develop literacy.19Richard Van Dongen, “Children’s Narrative Thought, at Home and at School,” Language Arts 64, no. 1, Literature and Literacy (January 1987): 82.

So while composition teachers may no longer assume that students in their degree programs bring with them the skills to understand classical forms, they can assume that these students possess an understanding of narrative. Composition teachers can likewise assume that their students comprehend the creation and resolution of tension within stories, and are able (at least in a limited context) to create narratives with solid structures, that is, stories with clear characters and settings, in which the conflicts that motivate the narratives are cogent and visible. The composition teacher who can design his or her pedagogy around these understandings can begin to teach their students about form, structure, and tension from the outset of their lessons, regardless of what musical skills the student brings into the composition studio.

Using narrative in the composition studio begins with helping the student understand the structures behind the stories, and the forces that make narratives compelling. The structuralist paradigms presented here can be valuable tools for doing so. Composers with this understanding of narrative forms can then rely on those forms to create more intentional musical structures, which is especially valuable for compositional novices who often write intuitively or from “left to right.” For a student with an intuitive approach to writing, decisions about compositional form and structure may be totally arbitrary, or guided but lacking intention. In short, the student may give his or her composition a contrasting section because that is what is expected. There may be a limited sense of interconnectedness between the various musical sections, or the whole piece may feel like “noodling” and lack a sense of direction or motivation. Introducing a student composer to narrative frameworks enables a broad-based discussion about intentional structures, and it also provides the composition teacher with tools for assisting the student to instill their compositional structures with nuance and sophistication.

Freytag’s Pyramid and “Consequence”

In the case of a student who is already writing sectional forms that lack intention, composition teachers can refer to the relationships inherent in narrative designs, which, after all, present not only a narrative sequence of events but also the creation and resolution of tension between conflicting forces. Consider, for instance, a student who is composing a five-part rondo and is struggling with the C section. The composer-teacher can recall that the relationship between the B and C sections of the form mirror the Play/Counterplay balance of Freytag’s dramatic structure, and then ask the student, “What are the consequences of the musical choices you’ve already made?” (Figure 7). This simple question creates multiple inroads for critically examining the music the student has already written. There may even be harmonic, rhythmic, melodic, or textural consequences, and the student may be inspired to reflect on any or all of these consequences in the C material they compose.

Figure 7: Five-part rondo, Freytag’s pyramid, and musical consequence

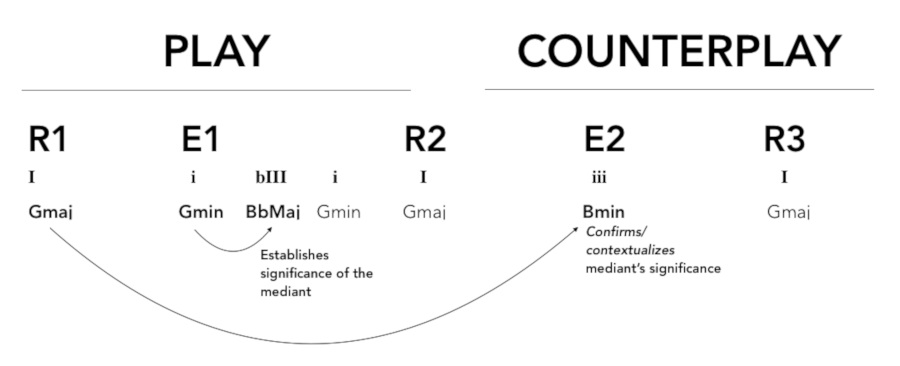

These narrative forces can readily be seen in Classical-era works that follow these formal designs. An example of a harmonic “consequence” can be found in the final movement of Haydn’s String Quartet in G major, Op. 54, No. 1, cast in a five-part rondo form (Figure 8). The quartet, and the refrains of the rondo, are in the key of G major. Haydn begins the first episode (the B section) in G minor, but cadences in Bb major, the diatonic mediant of that key. Following a brief diversion in Bb major, G minor is reestablished, and this episode ends with a strong half cadence, leading back to the parallel major for the second refrain.

Figure 8: Play and counterplay in Haydn’s String Quartet in G major, Op. 54, no. 1/IV

This harmonic framework proves to be a choice (Play) that is mirrored in the second episode (C section) by a consequence (Counterplay). This episode is in the key of B minor, the diatonic mediant of G major and a surprising key choice. This tonal motion mirrors that contained in the first episode in which G minor moves to its diatonic mediant, Bb major. Establishing B minor as a significant tonal area creates a larger context for the initial move to Bb major, and is essential to this movement’s sense of harmonic balance; the first motion to the mediant creates a need for a complementary motion elsewhere in the movement to confirm its structural significance. Haydn thus creates a Falling Action that is a clear response to choices made during the Rising Action.

The student’s conception of narrative (and of Freytag’s forces of Play/Counterplay) need not be limited to harmony; rather, it is in this definition of what constitutes a “consequence” of earlier musical choices that the student’s creativity can shine. The charge of the composition teacher is to ask the question and to challenge the student to develop an answer that furthers their expressive desires for the piece. Consider the case of Andrew, an undergraduate student in my composition studio at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL).20All students referenced in this article were consulted and gave permission to recount the events of their lessons. Respecting student examples, all names have been changed, and the musical examples offered in this discussion are original paraphrases and not the original intellectual property of any student. Andrew began his education at UNL with little formal musical training, having played for several years post-high school as the guitarist for a regionally successful bluegrass band. In his second year of composition study, Andrew composed a piece for a mixed ensemble that included both members of his band and performance majors within the School of Music at UNL. A veteran of popular songwriting, Andrew was comfortable writing pieces with defined formal blocks; however, with his mixed ensemble piece, he was trying to musically depict the actions of a short story, and so he wanted to develop a through-composed form that mirrored the story’s events. In the midst of the writing process, Andrew developed writer’s block, and our conversations turned to how I could help him get past it.

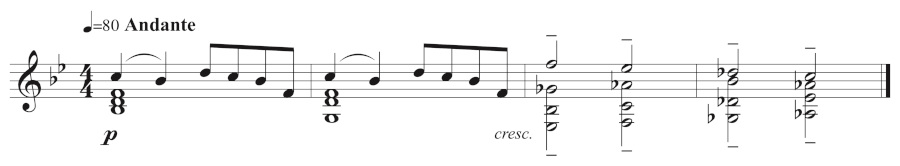

I began by examining the short story that was Andrew’s writing and pointed out the way it mirrored Freytag’s five-part design, including a marked division between Play and Counterplay around a central Climax. Andrew had written all of the material through his Climax, but he was struggling with the music that came next. Much of the material in the piece’s opening half was based on the development of a prominent melodic idea, which Andrew had created on his guitar (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Andrew’s opening melodic idea

Knowing that Andrew was developing the Counterplay of his piece, I encouraged him to think about the choices that he had made in the first half, and to develop answers to the questions those choices suggested. After writing out a distilled version of his main melodic idea, I asked Andrew, “What are the choices in this idea, and what are their consequences? Harmonically, melodically, rhythmically?”

Andrew examined his harmonic progression (Bmin7-C#dim-Bbmaj7-E7) and pointed out that only the Bbmaj7 did not work to reinforce the tonic of B minor. He wondered if that indicated Bb major’s importance as a tonal center in the second half of the piece. Andrew noticed that his melody was mostly comprised of ascending arpeggios with similar rhythmic profiles, and he maintained that all of the potential energy of this upward motion had to go somewhere—perhaps the second half could work toward a moment of melodic descent, maybe using more stepwise motion to contrast all of the arpeggiated skips in the first melody. Finally, he noticed that two of his chords, the first and last, were placed on downbeats, and the middle two were syncopated, occurring on the last eighth note of the measure. After some thought, Andrew suggested that in the second half of the piece, one of these conflicting placements would “win” the entire harmonic progression, and all of his chord changes would either arrive on downbeats or on the last eighth note of the measure. The discussion continued, and by the conclusion of the lesson, Andrew expressed that he had plenty of new ideas. The following week he brought in pages of new material, all based on a melody that reflected his Counterplay ideas (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Andrew’s counterplay melody

The Monomyth and “What Comes Next”

Let us revisit the monomyth concept, shown earlier to be a literary manifestation of the narrative forces of sonata form (Figure 11). It follows that this can be a valuable tool for teaching the student compositional skills generally associated with sonata form (e.g., thematic development, harmonic relationships, and modulation), even if that student does not yet possess the theoretical knowledge to identify such techniques. However, a student composer need not be writing a piece in rondo or sonata form to benefit from tapping into narrative energies; rather, he or she can benefit from considering the balance between the familiar and unfamiliar, the ordinary and the chaotic, and their effects on a listener’s experience. The lessons of the monomyth for sonata form can be distilled and universalized, made to guide just about any composition.

Figure 11: The monomyth and musical relationships

To begin, the forces of Order and Chaos that motivate the monomyth, and which guide the thematic and harmonic elements of sonata form, are not limited to the harmonic and melodic domains of a composition. Defining “Order” as material that the composer intends to present as familiar and free of conflict (often the first, or early, material encountered) allows for this material to be defined by any number of characteristics, such as texture, tonal language, or instrumentation, among others.

The composer’s definition of Order is principally important because it enables an understanding of Chaos, the material that constitutes the “opposite” of Order. This dichotomy is central to narrative, shown to be (at least within the context of the monomyth) a study of the evolving relationship between opposing forces, and as such, it can be instrumental in helping students understand the role and importance of musical contrast.

Perhaps more important, the Order/Chaos dichotomy is a powerful tool for helping students negotiate the intimidating question of “what comes next” in a piece of music. Often idea fatigue comes at the point where a student feels he or she has exhausted a material set, and is not sure what new material the composition demands. The composition teacher might reference the monomyth at this moment and ask the student, “What is the opposite of the music you’ve written?”

Similarly, narrative can guide the composer’s hand with regard to pacing and large formal considerations. Various elements of the monomyth can contextualize musical choices, giving the composer a valuable means of self-critique. For example, knowing that the Nadir of the Journey, the moment of greatest foreignness to the story’s starting point, occurs approximately halfway through the narrative might guide the composer’s placement of unfamiliar musical material. In addition, expecting the moment of greatest tension between the forces of Order and Chaos to occur shortly before the Return Across the Threshold can help a student understand the implications of his or her placement of their work’s climactic moments.21The chronological placement of this moment is ca. 65–70% through the narrative; readers might note that this mirrors the placement of the golden section, well documented as significant to musical works and many other types of narrative.

Simple, easily recognized embodiments of a monomythic struggle between two forces are ubiquitous in music, both within and outside classical music. The reader doubtlessly has intimate knowledge of works containing musical contrasts that could be interpreted as “Order vs. Chaos.” In lieu of an example pulled from the repertoire (which readers can likely provide for themselves), I offer a case study of how this approach might guide a student, again taken from my composition studio at UNL.

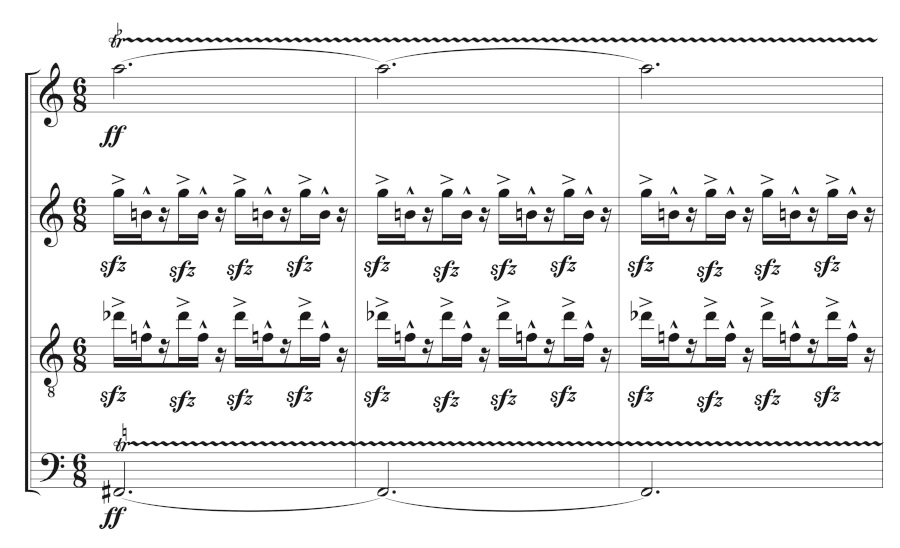

Tenia, a first-year master’s student in composition, came late to composing after studying music theory and woodwind performance during her undergraduate degree. A well-versed musician with a tremendous knowledge of repertoire, Tenia’s compositions were intensely creative, making adventurous use of harmony and jazz-inspired rhythmic tropes; however, by her own admission, she struggled with the formal pacing of her compositions and was hampered by severe writer’s block.

In her first semester, Tenia worked on a saxophone quartet. Through sketching and precompositional exercises, she developed a narrative for the piece: an understated, tonal hocket-like idea that would slowly grow more complex and darker in language, going through several transformations before climaxing, which would then lead to a chorale texture derived from the opening pitch material (Figure 12). We discussed her overall intention for the piece as instilling a sense of gentle excitement in the listener, leading to great tumult before the cathartic release of the chorale, which represented a moment of clarity after feelings of indecision and anxiety.

Figure 12: Tenia’s opening idea

While Tenia wrote the piece’s first and last ideas—the hocket and the chorale—with effortless inspiration, she found the middle material to be extremely challenging. None of the creative or developmental strategies she was using yielded music that sounded “right,” she claimed. After writing and discarding several drafts, she came to her lesson frustrated and unsure what to do.

I began by revisiting her intention for the music with which she was struggling, asking: “How do you want this music to make your listener feel?” Tenia responded by saying she was hoping to create a sense of anxiety in her listener. I then asked her to place that intention in context: “How does that feeling contrast with the feeling of your opening music?” Her opening, Tenia observed, was meant to feel quietly energetic, but comfortable. We then discussed the ways in which these two concepts were opposite, and how they were similar, then turned our attention to the monomyth.

Tenia readily agreed with the suggestion that the opening music, meant to feel comfortable to the listener, represented Order in the musical story she hoped to tell. By extension, she concluded, the anxious music she wished to write represented Chaos. When I asked her to specifically define the point of the story at which this music resided, she pointed to the Nadir of the Journey: a purely Chaotic moment that bears little or no resemblance to the music of Order, and might well be diametrically opposed to it.

We had already defined the emotions associated with this new music—anxiety, confusion—as the opposites of the comfort and familiarity in her opening idea. “So,” I asked Tenia, “what are its musical opposites?” Within a few minutes, she had identified several possible answers. The opposite music, Tenia suggested, could use a dissonant, nontertian harmony to contrast with the light texture and Lydian implications of her opening idea. It could occupy a high tessitura, rather than the mid- to low register that defined Order. The counterpoint of the opening music could be challenged by a monophonic texture, or it could be paired with an even denser counterpoint in which the regularity of the hocket is replaced with totally independent lines, perhaps even in multiple meters or tempi at once.

The goal, we agreed, was not to use all possible opposites, but to define and create that music which could represent a true opposite in some audible, tangible way. Tenia left her lesson energized, and by our next meeting she had nearly finished the piece, including the challenging middle section. The resulting musical texture used many of the ideas that she had suggested during her lesson, but she also introduced the “Chaos” concept to other elements we had not discussed (Figure 13). The slow, lyrical articulation of the opening was replaced with repeated sforzandi and rapid trills. In addition, Tenia decided to answer the ascending perfect fifth that defined her lower voice in the opening section with moving lines based on dissonant descending intervals in the middle one.

Figure 13: Tenia’s chaotic musical texture

Once again, this level of narrative understanding enables the student and teacher to have empowered discussions about “what comes next.” A frustrated student wrestling with writer’s block may feel as if he or she is encountering an impenetrable brick wall. In response, the composition teacher can challenge the student to define where he or she is in the monomythic story form. What, at that moment, is the balance between Order and Chaos? How are the forces interacting, and how have they changed or been changed by external forces? Now, the composition teacher might say, “Look ahead to the next station of the story. What’s different? Is there more Order, more Chaos, or a different level of balance between the two? What might those differences mean for the music and for its thematic, melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, or textural content?”

Conclusion

Composition teachers using narrative designs as pedagogical tools can help their students transcend difficult creative moments. Students of all ages and degree levels consume narrative in nearly every aspect of their lives, in forms that extend far beyond the music to which they listen. A composition teacher who is able to translate the lessons his or her students have learned through literature, television, and film into a better understanding of the balance and pacing of musical form greatly expands his or her perspectives about leading students to lasting artistic growth.

The use of narrative designs in teaching composition is not meant to be prescriptive or to suggest a dogmatic view of compositional quality. The suggestion that a student who encounters writer’s block study the monomyth need not mean that all music should conform to the monomyth’s framework or dichotomy, for narrative is a guide, not a limitation. I offer the suggestion to the reader in the spirit that a larger set of strategies for helping students solve problems is always useful.

The composition teacher who finds a place for narrative design in a pedagogical approach may discover that reliance on these frameworks can help students create with more freedom and expression. While observing the relationship between narrative and the development of literacy, Van Dongen observed that young students given narrative assignments would tell stories informed by (but not necessarily drawn verbatim from) their cultural context, particularly if those students came from indigenous cultures.22Van Dongen, 80. The universality of structural narrative designs allows each student to imprint their own cultural backgrounds on them more freely than on formal designs associated with European classical music. So rather than being restrictive for student composers, narrative designs can be liberating. Students can use these paradigms to realize their creative voices in familiar terms, and perhaps even more, integrate their cultural backgrounds into their musical expressions.

Notes

1. Sabine Feisst, Schoenberg’s New World: The American Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 225.

2. Sylvia Parker, “Understanding Sonata Form through Model Composition,” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 20 (2006): 135.

3. Michael Searby, “‘Composers Are Born and Not Made’: Some Preliminary Thoughts On How To Construct A Pedagogy For Music Composition,” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 31 (2017): 254.

4. Roland Barthes, “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative,” trans. Lionel Duisit, New Literary History 6, no. 2, On Narrative and Narratives (Winter 1975): 237.

5. The intimacy of this relationship between music and narrative need not be taken at face value. Indeed, existing structural models for musical forms bear deep-seated resemblances to several structural narrative forms.

6. Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces, 3rd ed. (Novato, CA: New World Library, 2008).

7. Campbell, The Hero, 196.

8. Campbell, 6.

9. Charles Rosen, Sonata Forms, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1988).

10. Rosen, 9–10.

11. James A. Hepokoski and Warren Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

12. Hepokoski and Darcy, 251.

13. Hepokoski and Darcy, 243.

14. For examples of such filmic and literary traditions, see, respectively, Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 3rd ed. (Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007), 3; and Steven R. Phillips, “The Monomyth and Literary Criticism,” College Literature 2, no. 1 (Winter 1975): 1–16.

15. Gustav Freytag, Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art, trans. Elias J. MacEwan (Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Co., 1894), 115.

16. Freytag, 106.

17. Zach Tomaszewski, “Marlinspike: An Interactive Drama System” (PhD diss., University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2011), 31.

18. Hayden White, “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality,” Critical Inquiry 7, no. 1, On Narrative (Autumn 1980): 5, 6.

19. Richard Van Dongen, “Children’s Narrative Thought, at Home and at School,” Language Arts 64, no. 1, Literature and Literacy (January 1987): 82.

20. All students referenced in this article were consulted and gave permission to recount the events of their lessons. Respecting student examples, all names have been changed, and the musical examples offered in this discussion are original paraphrases and not the original intellectual property of any student.

21. The chronological placement of this moment is ca. 65–70% through the narrative; readers might note that this mirrors the placement of the golden section, well documented as significant to musical works and many other types of narrative.

22. Van Dongen, 80.

References

Barthes, Roland. “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative.” Translated by Lionel Duisit. New Literary History 6, no. 2, On Narrative and Narratives (Winter 1975): 237–72.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero With A Thousand Faces. 3rd ed. Novato, CA: New World Library,2008.

Feisst, Sabine. Schoenberg’s New World: The American Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Freytag, Gustav. Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art. Translated by Elias J. MacEwan. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Co., 1894.

Hepokoski, James A. and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Parker, Sylvia. “Understanding Sonata Form through Model Composition.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 20 (2006): 119–37.

Phillips, Steven R. “The Monomyth and Literary Criticism.” College Literature 2, no. 1 (Winter 1975): 1–16.

Rosen, Charles. Sonata Forms. Rev. ed. New York: Norton, 1988.

Searby, Michael. “‘Composers Are Born and Not Made’: Some Preliminary Thoughts On How To Construct A Pedagogy For Music Composition.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 31 (2017): 251–61.

Tomaszewski, Zach. “Marlinspike: An Interactive Drama System.” PhD diss., University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2011.

Van Dongen, Richard. “Children’s Narrative Thought, at Home and at School.” Language Arts 64, no. 1, Literature and Literacy (January 1987): 79–87.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007.

White, Hayden. “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality.” Critical Inquiry 7, no. 1, On Narrative (Autumn 1980): 5–27.