Music analysis is not necessarily a complicated nor esoteric process. It is not even remotely akin to any branch of mathematics, except by virtue of an occasional shotgun marriage we find reported in our learned journals. The child who notes that the middle phrase of a song is quieter than its accompanying phrases has made a rudimentary analytical observation; he has broken up a whole into component parts to define the nature of a relationship.

At the other end of the analytical spectrum, of course, is the elaborate dissection, in which a complex tonal fabric is ripped into its irreducible threads, the better to comprehend its nature as a part of human experience. But this elaborate process is no more than a grandiose extension of the child's method, and its goals need not be basically different.

It is crucial that we recognize and appreciate the full range of analytical potentialities in music. To imagine analysis an act whose end must always be a singular result—a "one-of-its-kind," a "true" picture of musical reality—both ignores the dynamic nature of human perception and postulates a singular and unchanging goal for all analysis. Both of these false bases can, and do, produce gross misunderstandings among musicians about the value of analysis and its bearing on the art and theory of music.

There are possible, in fact, many quite accurate and "true" analyses available from any one piece of music, none of which entirely duplicates another. This variety is inevitable because analysis is interpretation, and interpretation necessarily entails the peculiar view of the interpreter. Having made this admission, however, we also must observe that there are basic aspects of any object, musical or otherwise, that are publicly verifiable and thus not subject to the fantasy of a private imagination. We must trust, certainly, that there are common grounds all experiencers of music can share; human psychology is not so variegated that we must assume my experience of a particular musical passage to be altogether different from yours, or, for that matter, totally alien to the experience of one from a different time or culture. If we imagine each listener's experience of a particular work as a field represented by a circle, the tacit assumption of any sincere analysis of that work is that there will be points where all circles intersect.

It is these common grounds, these fields of intersecting experiences, that most interest me as a theorist. They strike me as being the heart of the matter for the analyst, and I am convinced it is within this area that a continuity of musical utterance—a universal taxonomy of music—is to be sought. Here we may witness the common bases of music, and corollary to this observation is the realization that all music, if properly classified as musical, shares in some way one or more of these bases. To be music, after all, is to bear observable characteristics which belong to the genus. To possess more or less than three pairs of legs is to be non-insect; and, by analogy, to be composed of frequencies below 18 or above 18,000 cycles per second is to be non-music. (I trust that my point is clear without further, perhaps less obvious, documentation.)

Analytical processes in the contemporary physical sciences have rubbed off to an extraordinary degree on music theorists and historians during the past twenty years. In these more sanctified fields of inquiry the focus of analysis is upon interpretation of a sort, but here interpretation is wrought essentially from enumeration and classification. The chemist-analyst sifts and weighs until he can itemize the elements of his compound; the physicist plies his trade through what amounts to a counting process, his goal being to determine the atomic and sub-atomic content and to deduce gross form models (of a highly inferential nature) about any matter under scrutiny.

The analytical musician has been impressed by these procedures, primarily because their fruits are so palpably evident, and secondarily, I fear, because the techniques engaged for these tasks strike a deep yearning for the "objectivity," for the "certainty," for all of those states of knowing which scholars in the arts frequently feel to be lacking in their pursuits.1

There is no question that the techniques of the physical sciences can yield relevant information for the music analyst when properly applied. For example, one can count the occurrences of all pitch classes in a Chopin Nocturne, tally the results, then assemble an impressive table of statistics. With such information one can even show that, in terms of quantities alone, pitch usage in Chopin is not what it is in Dunstable. Much of what now enjoys the approbation of musical analysis does not extend much further than just such a process of tabulation of particles and comparisons of quantities. In some instances the particles are pitches, in other instances they are chords, but any discrete element of the tonal world is amenable to the nose-counting process. The technique is easy, the results are verifiable, mathematically indisputable, and, for the unwary musician, reeking with the seductive aroma of "scientific method."

The fantastic maneuverability of the electronic computer extends the reaches of this kind of analysis far beyond our current ability to utilize them. The day when every jot of one composer's total output can be scrutinized and compared with another's surely is not far off. As analysis, we are promised a great deal; but one wonders if this is empiricism properly applied, to an area whose very being depends upon the nature of the human response, the way in which the human psyche transforms sensory input into meaning.

It seems clear that we must differentiate between two related but nonetheless distinct goals for music analysis, each of which demands its own set of assumptions and working procedures, each of which produces quite different information about music. On the one hand there is the statistically oriented analysis whose aim is to lay bare what we may call the "atomic structure" of a work. Such an analysis is not necessarily concerned with music as an auditory experience; on the contrary, its goal is to ferret out all isolable particles—pitches, durations, sonorities, timbres—what have you, and to show in what quantities and orders these occur. It should be obvious that this goal demands no reference to auditory experience; a printed score provides all the raw data with sufficient accuracy to ensure precise identification, classification, and enumeration. Furthermore, the analyst could fulfill the requirements of this task without prior experience of music as sound, so long as he has learned the rules of musical notation and minimal guides of musical taxonomy.

The most notorious examples of this form of analysis exist today in some of the tedious guided-tours of serial works one finds scattered through professional journals. Such analyses may (and they frequently do) reveal for us some aspects of the composer's working procedures, and in this sense they are informative and cogent. They frequently do not reveal anything about perceived structure, however, and it is here that they fall short of a second goal of analysis, a goal which I like to think is the more proper end of the analytical process. This second goal is musical understanding, and this end is not approachable with statistical procedures unless every potential determinant of the musical experience is subjected to the measurement. The most precise and thorough data about pitch occurrence is made meaningful only if it be studied in the light of all other relevant facets of the musical experience, and this would involve concepts of experiential dynamics which are not formulated at the present time.2

Even some of those theorists one might suspect most of equating mere dissection with analysis have been careful to avoid this error. In speaking of the invariant properties that are potential in twelve-tone technique, Milton Babbitt has noted that ". . . the degree to which [these invariant properties] are projected explicitly in compositional terms depends upon the emphasis they receive from other musical components: rhythm; dynamics, register, phrasing, timbre, etc." Mr. Babbitt is saying, I believe, that the function (or "meaning") of any particle within a music texture is determined not just by its own nature, but rather by its role within a multifaceted complex, which is the compound of the musical experience.

Any analysis of music that does not go beyond the mere acts of identification, classification, and tabulation leaves out the main attraction of the journey.3 Schoenberg made this explicit in a letter of thirty-three years ago when he admonished Rudolph Kolisch for mistaking facts of compositional procedure for facts of musical being. In his letter, Schoenberg implies the same crucial distinction between "descriptive analysis" and "interpretive analysis" which I make here. In reference to Kolisch's analysis of the row in his Third Quartet, Schoenberg asks,4 ". . . do you think one's any better off for knowing it?" "This isn't where the aesthetic qualities reveal themselves, or, if so, only incidentally. I can't utter too many warnings," Schoenberg continues, "against overrating these analyses, since after all they only lead to what I have been dead against: seeing how it is done; whereas I have always helped people to see: what it is!"

Schoenberg provided us here with a terse distinction between these two possible goals of analysis. It is too bad that all of us since 1932 have not weighed the implications of the distinction more carefully.

In an article called "Analysis Today,"5 Edward T. Cone distinguishes between three levels or procedures of musical tinkering which he labels the "descriptive," the "analytical," and the "prescriptive." In his view, processes that do not discover and explain relationships, as they exist potentially in experience, are not properly called "analysis." Description, according to him, consists only of the blow-by-blow itemization of tonal events, and prescription is any extrapolation that suggests events or relationships which go beyond public verification. According to Mr. Cone's definition, "Analysis . . . exists precariously between description and prescription, and it is reason for concern," he continues, "that they are not always easy to recognize."6

The crux of the analysis problem in music is that the musical substance is not altogether analogous to the physical substance of the chemist or the physicist. The very existence of music within the time continuum of the apprehending listener imposes a dimension that is not cogent—at least, not in the same way—to our understanding of matter. In music it is not the atomic statistic that reveals structure; although relevant, such a statistic restricts the data to acoustical phenomena at best, or marks on manuscript paper at worst. In music it is within the relations of the smaller bits, as they are organized into patterns of larger dimension in the assessment by the listener, which are the determinants of structure. No mere verbal or symbolic itemization of discrete parts can capture the tonal embodiment of abstract life, which, in a metaphorical sense, music is, unless the, intermediary with the acoustic source is taken into account.

Analysis in this sense is different from what Mr. Cone calls description and Schoenberg terms how it is done. Here analysis entails an act of interpretation that moves beyond itemization and tabulation; properly applied, this kind of analysis comes to grips with more than the explicit data of acoustics or the stereotypes of traditional classification, for it recognizes and attempts to account for the latent or implicit factors provided by the listener within the act of cognition.

We can state this in fancier epistemological terms by saying that the music analyst cannot rest his case on a conformal theory of musical reality. Such a theory presumes that music exists in some "objective" state anterior to auditory experience, as marks on paper or as oscillations of reeds or strings or air columns. The most blunt rejection I know of such a basis was made by the aesthetician Andrew Ushenko, when he said that "Explicit sense data, for example colors in painting or sounds in music, are not enough for art, since they are perceivable—by animals as well as by unimaginative people—outside of aesthetic experience."7

The big conclusion I draw from these postulates of analysis is that any piece of music, no matter from what culture, from what era, from what composer, must be approached with the same yardstick in hand. Let me hasten to warn that I did not say "all pieces of music exhibit precisely the same characteristics and to the same degrees." Obviously not. My point is, rather, that the initial thrust of the analyst must be toward those matters which cause any work under scrutiny to be music, and how they are mixed to achieve that state. In this view, individualistic and distinctive traits of style are peripheral and are tended to only after the more significant questions of basic structure have been asked and answered.

Current fashion does not make my position particularly comfortable. The main focus of analysis during the past twenty years has been what we and our university catalogs have come to call "style analysis." The main object has been, I believe, to detect differences rather than similarities in music, to tote up the various peculiarities of any work which help to reveal its variance from some referential norm. By nature, this kind of analysis tends to overlook or soft pedal those factors in any work that relate it to music in general, although this certainly is not unavoidable.

In the face of a multitude of different styles—one might even say a multitude of different musics—from the many cultures remote from our own in time and geography, some musicians have concluded that "Every work must be approached on its own terms; each demands its own peculiar analytical presuppositions and procedures."

| * | * | * |

And still another straw in the wind of fashion helps to cast a pall over learned musicians every time music and universals are uttered in the same breath. The well-known inadequacies of all general theories of music, from Aristoxenus through Hindemith, lend an air of incredulity to any brave new hope that musical analysis can fruitfully apply a single set of wrenches to the wild variety of nuts and bolts of our world's music.

It seems evident, however, that the shortcomings of the past do not prove the inaccessibility of the goal. Just as Newton's speculations were fruitful for a limited universe—the universe known empirically to him—so the theories of Descartes and Rameau and Schenker must be regarded as reflections of a limited tonal world. The musical world is an expanding world too, and theories of musical structure must be capable of subsuming the corners of expansion as well as the center from which they might take root. It should be obvious that no such theory will be available until there are guides which show us more clearly the modes of human experience, for this is the one unchanging window from which to view the total scene.8

The fundamental postulate for any singular view of music must be that the human psyche is unchanging, that the sensory—perceptual—cognitive processes of the most ancient of our forebears were essentially (not totally) the same as they are for us and shall continue to be. Such a postulate clearly is subject to revision or abandonment; there is adequate circumstantial evidence to build a convincing case for it, however, so we are free to accept its validity until evidence to the contrary. piles high enough to make it untenable.

The main difficulty with earlier all-inclusive theories of music is not just that they cannot be applied meaningfully to our most recent music; on the contrary, none of these theories adequately relates to earlier music either. Look to any discussion of musical form and you will find a shockingly restricted conception in which thematics are regarded as the sole determinants of organization. Only since Schenker have analysts been urged to notice that perhaps tonality also could have a hand in the delineation of musical design. But is it true that melodic patterns and tonality are the sole means available to the composer for the structuring of the form of his work? Even in a Mozart sonata, do textural deployment, textural density, harmony, pitch range, timbre, and a host of other sound factors contribute nothing to this delineation? Look once again (or better yet, listen), and I believe that our traditional guides of musical form will appear to be paltry guides which in some music tell us only a part of the story, in other music tell us nothing.

Or does any current theory of tonality give insight into the structure of music of the so-called period of "common practice," during which this phenomenon supposedly became crystallized and projected with the greatest simplicity? If the analyst's conception of tonality is bounded by notions of scales and chord progressions and key systems, then, again, the view is over restrictive and misses the perceivable facts.

One of the most dogged obstacles to the recognition of universals in music has been, curiously enough, our lagging understanding of earlier musician's conceptions of their own music. We have enjoyed an unprecedented glut of information, thanks to the historical bent of musicology within our immediate past, but information and understanding are not always synonymous.

Let me illustrate what I mean.

The educated musician has long cherished the cliché that the music of Palestrina and other renaissance church composers may be understood only as a product of compounded linear forces. He has been told too often that the composers of that time—the medieval polyphonists as well—did not conceive of their structures in vertical terms, that their art was one of purely melodic, i.e., "horizontal" images, and thus such notions as chord, harmonic progression, and tonality are not relevant to the apprehension of their music.

No sensitive musician who really listens to the music of Palestrina can swallow such a notion; he cannot even entertain the notion intellectually, aside from the evidence of his senses, unless he is first convinced that the 16th century perceptual processes were quite different from his own. Curiously enough, the vertical dimension—the harmony—of Palestrina's music is as controlled as the sonorities of the Bach chorale harmonization or the Mozart aria. (The student of 16th century counterpoint rapidly learns this or finds grave discrepancies between his "linearity" and Palestrina's.) Those who support the neat and compelling "linear basis" theory for this music are forced to invoke mysterious laws of divine intervention, one must presume, to explain away this unaccountable consistency of vertical organization.

A less problematic position recognizes, of course, that Palestrina—like any other composer worth serious attention—puts tones together in ways which can be reconciled with the human response. It is not easy to believe that CEG sounded together in 1580 evoked vastly different responses for listeners from CEG sounded together in 1965. Nor is it at all probable that a C major triad followed by an A minor triad was less a harmonic progression then than it was in 1780.

It is cheering to see growing evidence that the debilitating assumptions of stylistic exclusiveness are gradually withering away in some enlightened quarters. Theorists and musicologists who are not content to accept second hand accounts of earlier concepts and practices, and whose regard for common sense is highly developed, are wary of this imposed dichotomy of musical realities.

One instance of this clearing of the musicological head can be found in an article by Richard L. Crocker, in which the assumed distinction between our notions of harmony and those of medieval and renaissance writers is examined and found wanting.9 Mr. Crocker has shown that this fading notion stemmed from and was fostered by the mistaken inference that the pedagogical strictures of medieval theorists necessarily reflected personal listening habits.

According to Mr. Crocker, the notion is without basis. He says that "It seems to have arisen when modern ears were first confronted with medieval sounds; accustomed to "traditional harmony," the ear found the sound of medieval music meaningless or intolerable. But when viewed as the result of simultaneous melodies, the crudity of the progressions became acceptable, even interesting. In this way medieval music was made accessible to the modern mind, which was willing to attribute philosophic brilliance but not common sense perception to the musical contemporaries of St. Thomas Aquinas."10

The net result of Mr. Crocker's brilliant clarification, and its relevancy to analysis today, should be clear. It is that the sensory mores of our ancestors were not so different from our own as we have been led to believe. What does change from time to time is style, or what we might call "aesthetic predilections." The error of the musician has been to confuse the fashionable. surface with the structural basis, and herein lies the myopia.

I can make still another example of the untenable view that fundamental parallels cannot be drawn between medieval music and concepts of our own day.

The long-perpetuated ruling that modality and tonality are mutually exclusive properties is another myth that has been sanctioned by a too-literal reading of the ancients. The cliché still persists that music written before such-and-such date (the date changes with the author!) is modal music; it does not—it cannot, the argument goes—exhibit the property of tonicality which we know in the music of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, because "the laws of tonality" were not discovered until a later date.

This idea perhaps comes to us directly from Fétis, who was the first to use the term "tonality." In Book II of his Traité he carefully warns the reader not to mistake mode for scale in the "modern sense." The analogy is misleading, he tells us, ". . . because not having either tonic or dominant in the tonality of plainchant in the sense attached to those words in modern music, the character of repose and conclusion inherent in those notes in modern music does not exist in the music based on the ancient tonality." The error of Fétis, of course, was in attributing to notes of scales inherent characters of repose and conclusion, for these phenomena exist in music, not in pitch abstractions (which scales and modes both are) that have been derived therefrom. If any music exhibits repose or conclusion, it will be produced by the dynamic relationships formed by its totality of parts, not because of some pre-experiential abstraction. Does plainchant exhibit these properties? If it does, then we have a significant parallel to draw between it and later music, and if scales or modes are not the causal factors, then we must throw them aside and look to more plausible frames of reference.

I cannot read the passage quoted from Fétis and reflect on its implications without being reminded of an undergraduate theory class in which my instructor carefully guarded the purity of modality from any crossbreeding with tonal concepts. In all seriousness, he would play or sing a troubadour melody composed of pitches c-d-e-f-g-a-b-c' with what to my young ears gave an unmistakable effect of C major. But, alas, the unqualified wisdom of the ancients was invoked and, my teacher was careful to point out, the melody in question was really in the Ionian mode. I spent many frustrating moments trying to rationalize this auditory mystery; my senses clearly were not up to the task. But I finally gave up the struggle, as one would suspect. I finally decided that Ionian modes and major scales are like Assistant Professors and Full Professors: there are no intrinsic differences; one has just been around a little longer than the other. But perhaps more important, I concluded from this small discovery that two things which sound the same must be classified as likes, no matter what presumed rules of semantics might be violated.

The universals or constants of music the analyst must seek out are no more, but no less, than those factors of the human experience which are the necessary by-product of the listener's interception. Analysis suffers a serious malnutrition today because theorists are so pitifully ignorant of the nature of perceptual processes. In general, musicians are even unaware of the relevance to their art of any information from the field of psychology, and psychologists with rare exceptions have been either musically illiterate or artistically naive (or both), thus precluding research that could lead us to solutions of the problems we face.

In spite of our admitted ignorance, however, the music analyst can maintain guidelines by which to make assessments and insights that are not inconsistent with what can be deduced about general experience. These guides are derivable from the same kind of empiricism that rests at the base of scientific method, an empiricism that blends intuition with observation and reflection. They can best be written only in the form of "If this, then that" clauses, and they certainly must be couched in the language of probability theory. To assume that the "laws" of musical experience are any less subject to relative interpretation than physical "laws" would be to commit the same sins we now suffer in the most elementary stages of our teaching of musical fundamentals, with its immutable "rules of the masters."

The observation of such guidelines in our deciphering of musical meaning would help us to avoid some of the hopeless non sequiturs we live with today. My point here is that any stylistic peculiarity of a particular composer cannot be judged outside the framework of general experience; the composer is free to adopt any working procedures, any compositional methodology he fancies, but the results of his labors eventually must be interpreted in a way that is consistent with the probabilities of human experience. Let me be explicit by citing specific examples.

It is commonly recognized that a unique feature of Wagner's style is his use of the appoggiatura, particularly the accented appoggiatura of extended duration. There is ample evidence in Wagner's music to support this view, and any analysis of the melodic-harmonic relationships in his music that does not respect this peculiarity risks creating a false picture of its structure. However, the indiscriminate application of this knowledge to any and all accented harmonic units of greater complexity than the triad can produce results that are not substantiated by experience.

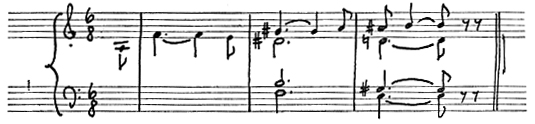

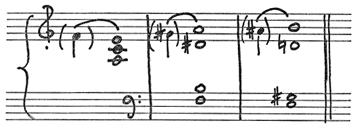

The example I have chosen to illustrate the way known stylistic considerations can lead to questionable interpretations has fascinated musicians since it was written, the opening of the Tristan Prelude.

The most widely accepted harmonic interpretation of this three-measure passage adopts a rather liberal view of the Wagnerian appoggiatura, a view that flys in the face of acceptable premises of perception. The passage is interpreted as the filling-in of three chords, a tonic A minor triad, a French augmented 6-4-3, and the dominant seventh of A. The implicit grounds for this reading are that the f ' in measure one and the  ' in measure two are protracted appoggiaturas, thereby carrying none of the "vertical" or "harmonic" weight that occurs in these locations. According to this analysis, the implicit harmonic weight of measure one is provided by the fifth relation of a—e', while the final A of measure two supplies the overdue completion of the augmented sixth chord.

' in measure two are protracted appoggiaturas, thereby carrying none of the "vertical" or "harmonic" weight that occurs in these locations. According to this analysis, the implicit harmonic weight of measure one is provided by the fifth relation of a—e', while the final A of measure two supplies the overdue completion of the augmented sixth chord.

If one accepts the premise that an appoggiatura can have a duration five times greater than its resolution, regardless of what metric or formal position it might occupy within its context,11 then this interpretation has merit. Seen in the light of perceptual probability, however, it asks us to flaunt a tenuous theory of "stylistic set" (in the psychological sense of that term) against a general perceptual set, and it is not difficult to rebel at the prospect. A regard for accuracy in analysis demands that we accept the given data and make our interpretations consistent with what we can expect in experience. If we do, the most salient feature of the Wagner excerpt turns out to be the melodic succession of f '— '—b', if for no other reason because these pitches occupy 13/17 (or 77%) of the mind's attention during this passage. In this view, the French augmented sixth chord disappears from the analysis (just as it does when we hear the passage!), replaced by the equally unstable but far more evident sonority—qua-sonority, the half diminished seventh chord.12

'—b', if for no other reason because these pitches occupy 13/17 (or 77%) of the mind's attention during this passage. In this view, the French augmented sixth chord disappears from the analysis (just as it does when we hear the passage!), replaced by the equally unstable but far more evident sonority—qua-sonority, the half diminished seventh chord.12

The result is an analysis that satisfies the most useful criterion musicians can apply to analysis: the way it sounds.

I shall make only one further example of the way in which sanctioned guides of style can mislead the analyst when they are not applied in ways consistent with or relevant to experience.

The history of music theory has suffered a lopsided view of the musical substance in regarding pitch relationships as almost the sole determinants of structure. In discussions from the earliest writers through current 12-tone theory one finds the bright spotlights focussed on pitch, to the detriment of rhythm, timbre, texture—in short, any other of the calculable facets of the musical pattern.

One of the by-products of this pitch fetishism has been the elevation of the scale to the position of final arbiter of musical classification. We all think we say significant things when we note that this piece uses the F major scale, that piece is in G Mixolydian, or the other passage is "Hungarian Chromatic" (whatever that might be!). A recent author of a twentieth century harmony text even discovers an abundant variety of modes within every few measures of relatively simple music, and we may be assured that the row-hunting of some current analysis is descended from the same excessive regard for the scale as the proper pigeonhole of pitch classification.

As a matter of fact, the variety of scales one finds in the music of various cultures has led many musicians to the conclusion that here alone is viable proof that there are no constants which bind all music into a common source. And yet, this conclusion is warranted only if it is assumed that scales do represent something basic and conclusive about the structure of the music from which they have been abstracted.

We are told that Bach, Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven wrote music that makes use of the major and minor scales, but in the next breath we are assured that these exclusive classifications demand a multitude of loopholes in order to represent pitch content, even in the music of the composers who were supposed to have depended upon them so completely. Like the mode classifications of Glarean, our rules of scale theory must incorporate a plethora of variants to supplement the norms, theories of combination and alteration and exclusion, for example, which, when considered seriously, merely beg the question of the referential norm—the scale—in the first place.

Of what relevance is our notion of the major or the minor scales to the pitch organization of Bach's music, as only one example, where ten or eleven or twelve different pitch classes are often packed together within a short span of time? Similar contradictions of the major-minor scale bias are too easy to find in the music of any composer of the common practice era to surprise us; the only surprise is the tenacity of this notion of scale as a meaningful reflection of the dynamic relations in any music. More fruitful would be serious consideration of scales only as shadowy abstractions of what Heinrich Schenker regarded as the musical foreground, the mere surface of the tonal experience. This revised conception would clear away some of the theoretical fog Hindemith wished to dispel when he noted that ". . . [scales] are not in themselves the material out of which melodies—and harmonies—are made."13

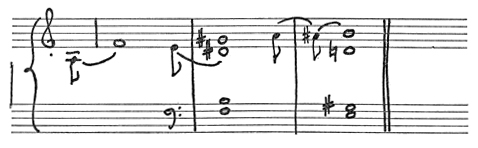

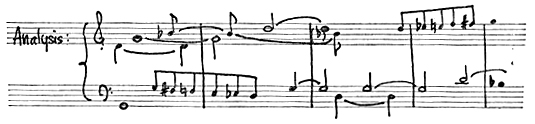

We might add to Hindemith's observation that scales also are not the stuff of the musical experience. If we abstract the pitches from the beginning of the Bach 2-part Invention in G minor, we can build a scale.

If we are honest, we must admit that this scale is not the simple major or minor pattern traditional nomenclature insists is basic to music of the 18th century. More important, we also must confess that whatever it might be named, this scale does not tell us a great deal about the music we wish it to represent. What does it reveal?

First, it shows us that the pitch focus for the passage, the tonic, is G. But this information had to be discovered before our scale could be drawn according to accepted rules of scalar construction.

And second, this scale shows us the respective pitch classes which occur in the passage, and here scalar revelations end.

More significant is what this scale does not show us about pitch organization. It does not reveal the significant role performed in the excerpt by the dominant octave pitch frame of d '—d " that structures the top line through its first three measures; nor does it reflect the forceful extension from the upper pitch of this frame, by means of a chromatic step-ascension, to the top G tonic in measure 5. To divulge the manner in which the respective tones of this passage are tied together in experience one must rely on analytical symbolism that at least shows time relations and hierarchies of function similar to the reduction methods developed by Schenker. The analysis shown below is an adaptation of this method, respective notation values representing levels of structural importance.

In short, our scale tells us next to nothing about the pitch basis or the pitch dynamics of the passage from which it is derived; analysis was terminated with the discovery of tonic. Admittedly, it is of some value to know that the pitch classes illustrated by a scale are the exclusive materials of the music, but this information is too abstract to provide more than a beginning for understanding; we know nothing from this abstraction about the relationships individual tones bear within the auditory process as the composer has ordered it. We can turn to the music of any culture in any era of man's preserved music and find the same limitations of scales to reflect pitch structure, as it related to experience.

| * | * | * |

In my questioning of some of the stereotypes of traditional analysis, I have touched only on the pitch parameter because, as I mentioned earlier, this has held an almost exclusive interest for the theorist in our history. Similar complaints could be directed at the limited categories we maintain in our attempts to understand the many facets of the musical substance. Certainly the element in music that demands the analyst's deepest intuitive resources, since he still lacks objective guides, is the time element, whether this be understood as the smallest architectonic level of "rhythm" or in its larger manifestation as "form."

Again, we can be assured that any postulates of rhythm will have to be derived from and remain consistent with what can be known about the actualization of time in the perceptual processes. It is certain that no amount of dissection and enumeration of acoustical or notational particles will help us to understand the structure of a series of tones unless we can know the probable transformation the comprehending mind will make of it. As Cooper and Meyer have made explicit, in their pioneer attempt to draw some rational conclusions from this dark area, "Rhythmic grouping is a mental fact, not a physical one."14 I can but add that if it is true, as I have suggested, that the perceiving listener operates according to unchanging and potentially calculable probabilities, then it is here that universals must be sought—not in barlines, in note beams, in meter signatures nor in quotations of statistics.

We would miss the truth, I believe, if we concluded that the two kinds of analysis I have contrasted here are mutually exclusive or that one is necessarily more valuable than the other. I trust that I have made clear which I believe to be most informative from the theorist's point of view, but the question of values depends for its answer upon the goals sought. My main aim has been to make explicit that these two approaches are distinguishable and that their relevancies to music are not identical. The analyst who wishes to reveal audible structure will not be handicapped by an awareness of every tiny particle in a work; and the analyst whose object is the atomistic reduction will find it difficult to make some decisions of classification that do not demand interpretive judgment. The two processes are based in different approaches to musical understanding, however, and they will reflect quite different images of their source if pursued in a consistent manner.

I might stress once again what appear to be the three main obstacles to the realization of the interpretive kind of analysis I have distinguished here that can reveal structural parallels in all music.

The first is our bashful reluctance to assume that all music can be approached with the same cognitive reflexes. In this sense, the monumental accumulation of historical data—theoretical treatises, the music itself, and the host of corroborative detail—have had the ironic effect of blinding us to the most obvious evidence of our senses.

Second, the theoretical abstractions of tradition—tertian chord theory, scale classifications, the exclusively thematic conception of form—all and others have a way of restricting vision, of directing our gaze away from the very things we wish to see most clearly. Incapable of adequately explaining even the music from which they were evolved, these ossified frames of classification prove misleading or irrelevant when applied to music of before or after.

And last, of course, is the observation that the music analyst is inconvenienced today because he must operate without any general framework of perception except that which he can project from an intuitive matrix. As musicians, we have neglected to ask and to seek answers for the very fundamental questions of what happens when tones are put together, and psychologists generally ignore our needs or feel reluctant at present to deal with them. Until inquiry of this kind has established some referential bed for general experience, from which we can extrapolate appropriate guidelines, the music analyst will be stuck with his homemade judgments about the ways in which tones become music.

Notes and References

1This folk-fiction of absolute objectivity in the physical sciences is not without its critics. For a recent debunking, see Arthur Koestler's The Act of Creation, particularly p. 252.

2It is doubtful that the current narrow stress in psychology of behavioristic studies of learning can ever lead to any useful concepts of this kind.

3Arthur Koestler's epigram re statistics is too relevant here to miss. It is: "Statistics are like a bikini. What they reveal is suggestive. What they conceal is vital." (The Act of Creation, p. 89.)

4In the letter dated Berlin, 27 July, 1932. Arnold Schoenberg Letters, ed. Erwin Stein, London: Faber and Faber, 1964.

5"Analysis Today," The Musical Quarterly XLVI (1960), 172-188.

6Ibid., p. 174.

7In Dynamics of Art, Bloomington: Indiana U. Press, 1953, p. 5.

8Such a conception does not preclude the peripheral cognitive "prejudices" that admittedly are effective for the individual and for the culture in general.

9In "Discant, Counterpoint, and Harmony," JAMS XV (1962), 1-21.

10Ibid., p. 1.

11Context is a crucial factor. If the suspected appoggiatura pattern fell at a cadence, for example, then the significance of the final tone of the pattern as a cadence pitch would justify recognition of the previous tone as of less structural weight, i.e., as an appoggiatura.

12Since our concern is for auditory structure, notation is not immediately relevant, so the  —b—

—b— —f is a half-diminished seventh chord (f—

—f is a half-diminished seventh chord (f— —

— —

— ).

).

13In "Methods of Music Theory," The Musical Quarterly XXX (1944), 24-25.

14The Rhythmic Structure of Music, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960, p. 9.