Abstract

This article explores tracing as an analytical method and a pedagogical tool. I define “tracing” as following a singular event throughout a work, tracking its evolution, and placing it in an overall narrative context. I use Chopin’s Mazurka in A♭ major, Op. 17, no. 3 to model a tracing analysis, tracking the development of F♭/E♮ across the work. The analysis shows not only how tracing can build a compelling analytical discussion but also how this methodology translates easily to the music theory classroom. I argue that integrating tracing into the undergraduate curriculum gives students a guided, focused introduction to the formidable task of building and supporting a musical argument.

Vincent Benitez

Initial Considerations

This article explores an analytical strategy that I call tracing and illustrates its potential in the music theory classroom. I define tracing as following a singular event throughout a work, tracking its evolution, and placing it in a narrative context. These events can range from a single pitch, harmony, or motive to elements like timbre, dynamics, and register.

One of the beauties of tracing is that it is relatively easy to incorporate into the music theory classroom. The concept is simple for students to grasp: (1) identify an event, (2) see how it develops, and (3) place it into context. This strategy is easy and fun to model in class, and students enjoy working through a piece and accumulating evidence that is focused on a particular idea. In addition, tracing encourages students to zoom both in and out: how can we understand this event’s function in this precise moment, and how can we come to terms with its development across the entire piece? Finally, tracing can provide the thesis for an analytical argument: “Event X plays a critical role in Piece Y by Composer Z. Let me describe how and discuss why I find it significant.” Tracing exhibits parallels to musical agency as well as narrative, two processes that have been heralded as gateways to successfully introducing undergraduate music students to analysis. I argue that tracing deserves a seat at the table, too. In what follows, I touch upon the above-mentioned methodologies and demonstrate how tracing offers a unique analytical lens. I then illustrate the technique with a model analysis of Frédéric Chopin’s Mazurka in A♭ major, Op. 17, no. 3, a piece that I have used successfully in a third-semester music theory course.

* * *

Most undergraduate music theory instructors strive for similar goals in the education of their students, among them achieving fluency in reading various clefs, identifying keys and key areas, labeling harmonies and functions, and navigating musical phrases and forms. And yet, many students struggle to place these observations into a context. Efforts to label vocabulary and understand syntax and grammar are for naught if we do not ask students to talk about their experience with the music—what they find striking, what is unusual or unexpected, and what draws their attention.

Indeed, bridging the gap between identifying musical events and using that information to build an interpretive stance is a daunting task. Teaching the basics of counterpoint, harmony, and form is often difficult enough, and asking for analytical depth and interpretive nuance can seem nearly impossible. Students can become overwhelmed when they try to decide what is important in a piece of music, formulate a thesis statement around those important elements, and craft an argument, with musical support, to strengthen a thesis.

Gordon Sly is a staunch supporter of using musical agency as the catalyst for students’ development of an analytical voice and viewpoint. He defines agency as “the capacity of some musical element or idea to influence the course of events” (Sly 2005, 52). Sly invites students to first identify a musical agent and then describe how it exercises control over the music’s behavior. He suggests that utilizing musical agency for analysis gives students a concrete focus, allowing them to “concentrate relentlessly” on the agent and build a compelling argument around it (Sly 2005, 52). This focus helps mitigate a trap into which many students fall: producing a grossly overgeneralized discussion that often amounts to little more than a blow-by-blow account of the music from first downbeat to double bar line. What is more, framing their theses around a perceived “control center” of sorts encourages students to utilize more lively, active prose. Writing about a musical agent that is in essence controlling the music’s progress is far more engaging than an essay on how one harmony leads to the next.

Tracing shows parallels to Sly’s musical agency in its focus—students identify a subject and construct their analytical discussion around its atomistic behavior as well as its larger-scale trajectory through a work. In other words, they build their analysis around one parameter. However, the subject of tracing is not synonymous with the musical agent as Sly defines it. Tracing differs from agency in that there is no implied force of influence—I do not propose that the subject exerts any leverage over the music’s progress, per se. Rather, I ask students to simply consider the subject as a salient feature of the work that can (and often does!) offer a compelling, multilayered understanding of the piece.

Matt BaileyShea agrees that “a focus on agency and musical narrative is . . . the best way for students to engage the most striking, expressive, and human characteristics of most Western music” (BaileyShea 2011, 9). BaileyShea dives even further than Sly into musical narrative, using the physical and emotional connections that we have with musical events as the guide for his classroom analyses.1See Fred Everett Maus (1988, 56–73) for perhaps one of the most influential looks into musical narrative. Maus’s discourse on effectively utilizing technical music-theoretical language, alongside affective descriptors, opened the door for a new and, I would argue, more powerful way of talking about music. He encourages students to explore character and dramatic development, often attributing “human drama” to the musical agent itself (BaileyShea 2011, 23). Seth Monahan offers a similar attribution when he introduces agency to his students. Monahan’s individuated elements include “any discrete component of the musical fabric that can be construed as having autonomy and volition—in other words, any element that could be understood as a kind of dramatic ‘character’” (Monahan 2013, 327). Where Sly suggests a musical agent exerts control over the piece, BaileyShea and Monahan fully anthropomorphize the agent—it has desires, whims, wants, and expectations. In fact, Monahan makes it a point to state that individuated elements do not, in fact, control the music; rather, they have a stake in the unfolding of events, but they do not fully direct the outcome.

Where tracing differs from BaileyShea and Monahan’s narrative agency is primarily in the scope and stability of its subject. Take, for instance, BaileyShea’s discussion of Chopin’s Prelude in E minor, Op. 28, no. 4 (BaileyShea 2011, 22–28). His analysis views the entire melody as one dramatic character striving for a primary goal: attaining tonic arrival on E5. The melody exercises all of the behavior we might expect from a character in a drama: it strains, it yields, it resists, it surges. Analytical discussion uses these behaviors to detail the agent’s dynamic journey toward its melodic goal. To contrast, a tracing analysis might choose one discrete musical event—perhaps the failed resolutions of D♯—and construct analytical discourse around that nexus. Such discourse might take the form of three questions: (1) How exactly do each of these resolutions fail to manifest? (2) What is happening in the moments before and after? (3) How does the denied tonic fit within that trajectory?2On this point, Sly and I are much more in agreement. See his sample analysis of Chopin’s Mazurka in F minor, Op. 68, no. 4, which identifies D♭/C♯ as the musical agent and discusses how it influences and directs the music’s development. The D♭/C♯ agent is similar to the musical event I propose as an ideal tracing subject.

BaileyShea and Monahan also suggest that an analysis does not need to be confined to a single musical agent: there can be multiple agents, and an analysis can focus on their relationship to one another. Monahan further fleshes out this notion of “shifting agency ascriptions,” identifying four hierarchically nested types of agencies: (1) the individuated element, (2) the work persona, (3) the fictional composer, and (4) the analyst (Monahan 2013, 322). He suggests that effective analyses move seamlessly among these agencies, creating multifaceted readings that emphasize at varying times the analyst, the composer, and the music itself.

Monahan’s malleable take on agency differs quite a bit from what I propose with tracing. When introducing tracing, I encourage students to whittle down their focus to not only one specific musical event but also one analytical viewpoint. I find this scope to be more manageable for undergraduates new to analysis, and it discourages papers that ascribe the entirety of a piece’s behavior to either composer or analyst. Rather than sentences such as “In his Prelude in E minor, Chopin writes a Fr+6 of A minor in m. 3 and then chooses to resolve it incorrectly,” students are compelled to make the music do something: “In m. 3, the D♯ of the Fr+6 fights against its upward resolution, falling instead to D♮ and then embarking upon a long chromatic descent.” Similarly, by giving the music intention and action, students avoid bringing themselves into the forefront of the discussion. Statements such as “I expect the Fr+6 in m. 3 to resolve to E major but am surprised when it goes to a Bø![]() instead” are less likely when students maintain their focus on the subject they are tracing and how it influences the music’s development. In this way, tracing not only encourages more attention-grabbing language but also keeps students acutely focused on the music itself—and out of the rabbit hole of the composer’s intentions or their own personal thoughts.

instead” are less likely when students maintain their focus on the subject they are tracing and how it influences the music’s development. In this way, tracing not only encourages more attention-grabbing language but also keeps students acutely focused on the music itself—and out of the rabbit hole of the composer’s intentions or their own personal thoughts.

The existing wealth of literature on agency and narrative would extend far beyond the scope of this article. It is sufficient to say that Sly, Monahan, and BaileyShea nicely detail the roadblocks to teaching analysis in the undergraduate sequence and offer clear and effective solutions to the problem. Tracing is an inviting third option. The remainder of this article models the tracing process using Chopin’s Mazurka in A♭ major, along with suggestions for approaching both the work and the methodology in the classroom. I conclude with some thoughts on tracing as a pedagogical tool, including its potential for core music theory courses as well as music outside the classical canon.

Tracing and Chopin’s Mazurka in A♭ major, Op. 17, no. 3

Chopin’s Mazurka in A♭ major is a quirky gem combining elements of the traditional Polish mazur—triple meter, a lively tempo, and second- and third-beat accents—with a few surprises along the way. Its themes cover a range of characters, and the music traverses an unusual modulatory scheme. After opening with a lilting A♭-major melody, the mazurka briefly dips into B♭ minor for a darker, more agitated theme before returning to A♭ major once more. Yet it is the modulation to E major that is the most striking. The diversion to the enharmonically respelled ♭VI brings with it a pair of charming melodies, one of which tonicizes B major.3With its slower tempo and flowing melody, the E-major theme seems to harbor characteristics of the Polish kujawiak, another folk dance often associated with the mazur. By the time the music returns to the first theme via a dal segno al fine, it has dabbled in quite an array of key areas: from four flats to a brief tonicization of a five-flat minor key, and then a sudden shift to four and five sharps. The changes in mood that accompany each shift create a colorful, unique piece wrought with idiosyncrasies.

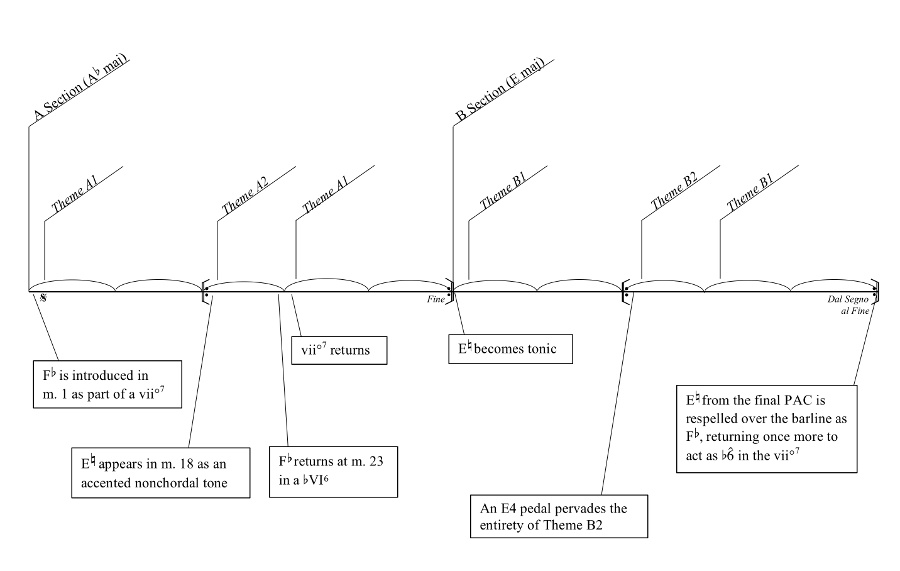

Figure 1. Overview of Chopin, Op. 17, no. 3 tracing the introduction, development, and resolution of F♭/E♮.

Figure 1 details the form of the mazurka while also featuring the journey of the chromatic pitch F♭. Annotations summarize the note’s chronicles, highlighting discrete phases of introduction, development, and resolution. F♭ first appears—conspicuously—in Theme A1, acting as ♭![]() in a vii°7. In Theme A2, it is respelled as E♮ and occurs as an accented nonchordal tone. It then regains its ♭

in a vii°7. In Theme A2, it is respelled as E♮ and occurs as an accented nonchordal tone. It then regains its ♭![]() designation and becomes part of a mixture chord in a retransition back to Theme A1. The B section is the culmination of the F♭’s evolution: respelled as E♮, it serves as tonic in the new key area, E major (Theme B1). E then remains as a pedal tone in Theme B2, and as the B section comes to a close, the E is respelled over the bar line as F♭ and resumes its original function as ♭

designation and becomes part of a mixture chord in a retransition back to Theme A1. The B section is the culmination of the F♭’s evolution: respelled as E♮, it serves as tonic in the new key area, E major (Theme B1). E then remains as a pedal tone in Theme B2, and as the B section comes to a close, the E is respelled over the bar line as F♭ and resumes its original function as ♭![]() . With this overview in mind, let us dive more deeply into the individual instances of the F♭/E♮ and place them in various contexts.

. With this overview in mind, let us dive more deeply into the individual instances of the F♭/E♮ and place them in various contexts.

Example 1. Chopin, Op. 17, no. 3, mm. 1–4, showing the F♭’s emergence on the first downbeat, as part of a vii°7 harmony.

The opening measures of Op. 17, no. 3 present a unique aural puzzle (see Example 1). A lone C5 in the right hand initiates the work as an anacrusis on beat 3—the notated accent is a characteristic use of second- and third-beat stresses in the mazurka genre. However, a tie over the bar line obscures the typical “short–short–long–long” mazurka rhythm.4Chopin uses similar right-hand ties over the bar line in several other mazurkas (Op. 6, nos. 1 and 4; Op. 24, no. 1; Op. 33, nos. 2 and 4; Op. 67, no. 4; and Op. 68, no. 4; in Op. 30, no. 1, the left hand does not enter until beat 2; in Op. 50, no. 3, it does not enter until the second measure), but those are accompanied by a strong tonic announcement in the left hand on the first downbeat. Op. 17, no. 3 is unique in its combination of the downbeat-obscuring tie, along with an opening harmony that is clearly not tonic. Although the left hand unequivocally announces the first downbeat, it does so not with the tonic, but with an especially colorful dominant. A vii°7 harmony emerges, turning the right hand’s C5 into a dissonant suspension. Not only are melodic and harmonic resolutions in limbo, but tonic realization as well. Many performers prolong the suspense, subtly resting on the opening harmony ever so slightly before advancing. The right and left hands then resolve in quick succession: the melody tumbles from ![]() to

to ![]() , arriving on tonic just as the left hand moves from vii°7 to I, shaking off the tension of an unsettled opening. The melody immediately reverses course to climb back to

, arriving on tonic just as the left hand moves from vii°7 to I, shaking off the tension of an unsettled opening. The melody immediately reverses course to climb back to ![]() , with melody and harmony alike repeating the same pattern twice more before a half cadence at m. 4.5Rudolph Arnheim might consider these initial measures in terms of “the dynamics created by the deviation or divergence from a norm base” (Arnheim 1984, 297). He defines a norm base specifically as a tonal center; I might expand that notion here to include any clear declaration of a key. Of course, most will hear the opening harmony as distinctly dominant, but that is only after the briefest flicker of surprise that it is not, instead, a tonic triad. This slight deviation from expectation creates a dynamic energy that draws us toward tonic. See Arnheim, (1984, 295–309).

, with melody and harmony alike repeating the same pattern twice more before a half cadence at m. 4.5Rudolph Arnheim might consider these initial measures in terms of “the dynamics created by the deviation or divergence from a norm base” (Arnheim 1984, 297). He defines a norm base specifically as a tonal center; I might expand that notion here to include any clear declaration of a key. Of course, most will hear the opening harmony as distinctly dominant, but that is only after the briefest flicker of surprise that it is not, instead, a tonic triad. This slight deviation from expectation creates a dynamic energy that draws us toward tonic. See Arnheim, (1984, 295–309).

Upon initial hearings of the piece, students in my sophomore music theory class describe the opening measures as “lopsided,” “crooked,” or even “awkward.” When pressed for more details, they acknowledge feeling initially unsure of the music’s key and meter, and are then lulled by the theme’s motivic repetition. The theme presents itself as a sort of hamster wheel, with a melody cascading from dissonant ![]() to consonant

to consonant ![]() , only to climb back up to and do the whole thing over again (and again). As each melodic suspension resolves and then proceeds to the tonic, the music repeatedly succumbs to gravitational pull.6Steve Larson and Leigh VanHandel identify “gravity” as the weakest of their four musical forces. The melodic pattern 3–2–1, as seen here in the melody, exhibits a gravity score of 1, indicating that it does experience musical gravity. I find this effect to be compounded by the 4–3 suspension and its resolution. See Larson and VanHandel (2005, 119–36). What is more, the F♭ within the vii°7 heightens the need for resolution by adding a second instance of half-step motion to the mix:

, only to climb back up to and do the whole thing over again (and again). As each melodic suspension resolves and then proceeds to the tonic, the music repeatedly succumbs to gravitational pull.6Steve Larson and Leigh VanHandel identify “gravity” as the weakest of their four musical forces. The melodic pattern 3–2–1, as seen here in the melody, exhibits a gravity score of 1, indicating that it does experience musical gravity. I find this effect to be compounded by the 4–3 suspension and its resolution. See Larson and VanHandel (2005, 119–36). What is more, the F♭ within the vii°7 heightens the need for resolution by adding a second instance of half-step motion to the mix: ![]() yearns for

yearns for ![]() , and ♭

, and ♭![]() also wishes to move to

also wishes to move to ![]() .

.

After we spend some time discussing their initial responses to the music’s opening, I set students loose to perform a harmonic analysis of Theme A1 (mm. 1–16). Since the theme is so repetitive, this only takes a few minutes and reveals several important features. Perhaps most striking is the significant exposure vii°7 receives—it occurs in nearly every measure. Many students are quick to identify this harmony as one of the culprits in their feelings of unease at the piece’s onset. We take time to identify the vii°7 as an instance of mode mixture, with the F♭ being borrowed from the key of A♭ minor, and then discuss the duplicitous nature of the fully-diminished seventh harmony. I play Chopin’s opening sonority, minus the right hand’s suspension, and resolve it to four different major keys: B, D, F, and A♭. And while we won’t tackle enharmonic reinterpretation of the vii°7 for a few more weeks, on this day I stress the aural implications of beginning a piece on such a sonority—implications many of my students felt when first exposed to the work. In highlighting the relevance of the opening harmony, I plant the seed that the borrowed F♭ is a marked, if not crucial, pitch in this work.7For influential work on markedness, see Robert S. Hatten (1994).

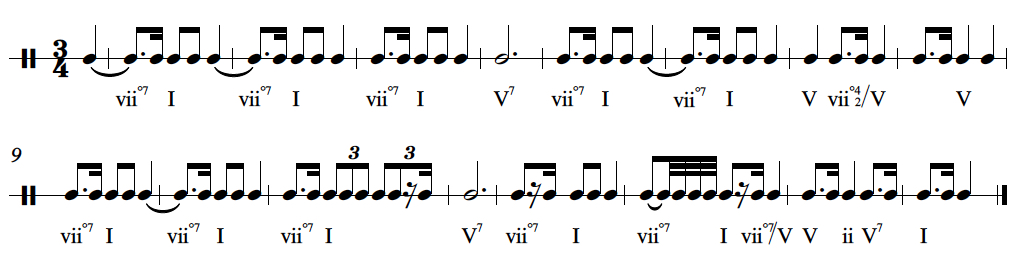

Example 2. Overview of Theme 1A (mm. 1–16), showing the prevalence of vii°7 and F♭.

After a deep dive into the opening vii°7 and its implications, I then ask the class to take a step back and look at the harmonic language of Theme A1 in its entirety. A glance at the overview provided in Example 2 confirms a harmonic palette saturated with vii°7, I, and V(7). Students identify a series of regularly-spaced half cadences (mm. 4, 8, and 12), which confirms a balanced phrase structure and also contributes to a sense of forward propulsion. At this point, I urge students to classify the harmonies thus far, which reveals that the predominant class is conspicuously underrepresented. As the final statement of the theme (mm. 13–16) moves toward an authentic cadence, it introduces a lone predominant harmony: a supertonic chord at m. 15.2. The harmony sets off a predominant–dominant–tonic progression that results in the piece’s first tonic downbeat at m. 16. Hemiola in mm. 14.3–16 further highlights the moment as the music rushes toward an authentic cadence at last.

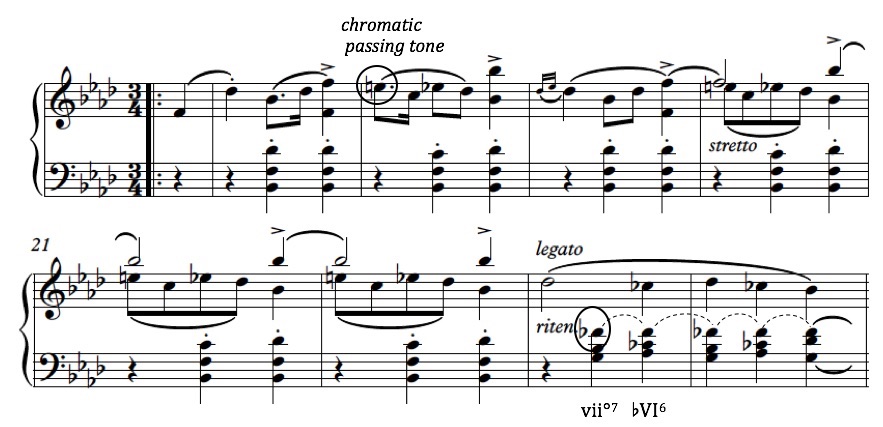

Example 3. Theme A2, mm. 17–24. The E♮ first appears in m. 18, and returns in mm. 20–22. F♭ then appears in the next measure. Dashed slurs highlight its retention as the shared pitch between the vii°7 and the ♭VI6.

When Theme A2, shown in Example 3, begins at m. 17, F♭ has been transformed into E♮ and subsequently plays a salient role in the eight-measure passage. The theme tonicizes B♭ minor, making the E♮ a chromatic pitch. As the angular melody confirms B♭ minor with arpeggiations over B♭ and F7, E♮ occurs on several downbeats (mm. 18 and 20–22). The metric placement alone is cause for attention, but the E♮ receives a slight agogic accent in its first appearance (m. 18), practically forcing its presence to be acknowledged. What is more, in each of its four iterations E♮ occurs either alone or with a tied note.8The absence of left-hand downbeats for nearly the entire passage is also quite striking, even suggesting a pending metric shift that never comes to fruition. Without harmonic support below, the chromatic pitch stands out even more starkly. As Theme A2 winds down, E♮ becomes F♭ once more. With the retransition to Theme A1 at m. 23, F♭ first returns to its familiar role as a member of vii°7 (Example 3, m. 23.2). Then, the following beat introduces ♭VI6, elevating F♭ from a borrowed pitch to the root of a borrowed chord. Indeed, as the harmonies in mm. 23–24 alternate between vii°7 and ♭VI6, the common-tone F♭4 explicitly fuses the two chords together.9We were first introduced to C♭ in Theme A1, mm. 7.2 and 14.3, as part of an applied vii°7. Here it reappears as the fifth of the ♭VI6. Both occurrences suggest a hint of A♭ minor. Later in Theme B1, this connection grows even stronger when the music briefly tonicizes G♯ minor. This is somewhat of a “bonus” feature that I may explore with more advanced classes if time allows.

The first thing I have students do with this passage is to identify the key area. Once they do, I pose the question: Did anything in Theme A1 suggest that the music might tonicize B♭ minor instead of, let’s say, the dominant? The prompt is enough for most students to draw a connection between the ii at m. 15.2 and Theme A2, and in turn encourages the class to continue looking for correlations across thematic and formal boundaries. We then move on to the E♮’s role in Theme A2. After students identify the pitch as both accented, chromatic, and passing, we spend some time discussing the implications of its metric placement. As with the vii°7, many students feel inundated with the E♮ due to both its prominence on the downbeat as well as its repeated presence. Finally, I ask the class to analyze the two harmonies in m. 23. By this point some students have picked up on the potential importance of F♭/E♮ and are quick to point out the F♭’s return. Once the class has identified the mode mixture ♭VI6, we zero in on the F♭4 that not only connects the ♭VI6 to the vii°7 but also helps usher in the return of Theme A1. As the music reiterates the familiar theme (mm. 25–40), I also make sure to emphasize that both the F♭ and the E♮ have been foreign to their respective key areas. These notes have managed to draw us in, not in spite of but because of their other-ness.

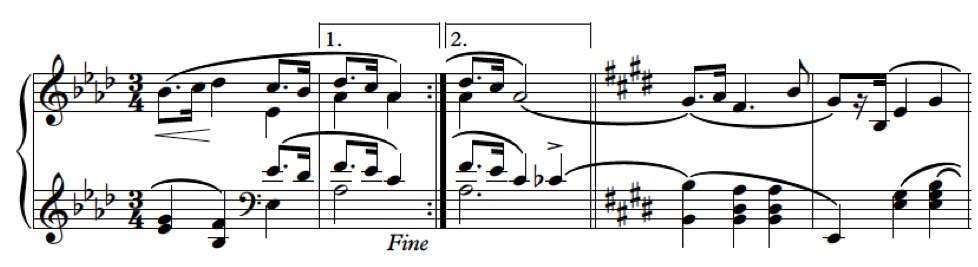

Example 4. Transition from the A section to the B section, mm. 39–42. Ties across the barline connect the A♭ and C♭ from one section to the next as they are simultaneously respelled as G♯ and B♮ to become ![]() and

and ![]() of the new key, E major.

of the new key, E major.

The transition to the B section, shown in Example 4, contains a subtle reference to the piece’s opening: ties over the bar line create metric ambiguity as A♭ morphs into G♯ and C♭ to B♮, ushering in the new theme as well as a new key area. Here too many performers luxuriate, exacerbating the feeling of metric insecurity. Harmonic arrival at m. 42 confirms the new key of E major. This moment is the pinnacle of the chronicles of F♭/E♮, that is, from chromatic pitch to borrowed harmony to, finally, tonic.10Brian Alegant and Donald McLean describe a similar process as “enlargement.” They focus on the temporal enlargement of a surface-area object. Although temporality does play some part in the Chopin—the B section of E major is, of course, a much longer manifestation than single harmonies or pitches in the A section, the focus is more on the changing roles of F♭/E♮. See Alegant and McLean (2001, 31–71). The structural enlargement of F♭/E♮ is complete.

Indeed, the first thing I do when approaching the B section in class is to ask students to speculate on the new key area, E major. At this point in the theory curriculum, students have had little to no exposure to chromatic mediant relationships and as such, have no way of recognizing that connection here. Yet most do understand that the keys of A♭ and E major are not closely related, and that E major is perhaps a peculiar destination. More importantly, due to our consistent emphasis on the F♭/E♮ thus far, many draw the crucial connection that the E major key area’s origin can be traced to the first measure of the piece in the chromatic F♭.

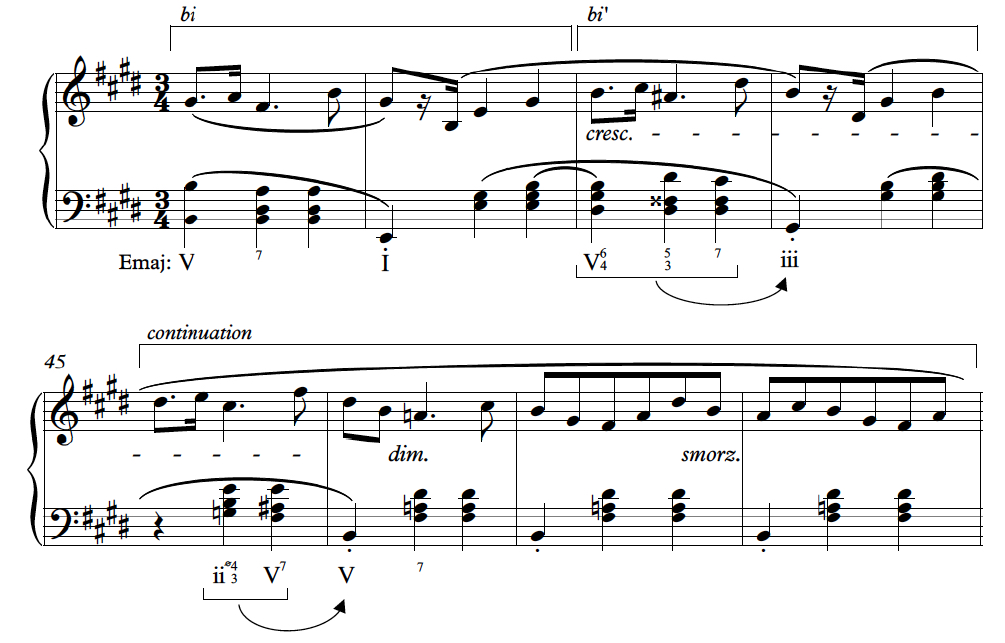

Example 5. Theme B1, mm. 41–48. The sentential phrase structure is diagrammed above the staff, and a harmonic analysis shows the tonicization of the members of the E major triad.

Theme B1’s appearance in E major is undeniably the highlight of the class, and students are able to experience the satisfaction that comes along with a successful tracing analysis. Yet, I would be remiss to simply stop there and let us bask in the glow of discovery. The music still has much to offer, some of it even beyond the scope of F♭/E♮. With its sentential phrase structure, lyrical melody, and liberal use of tonicizations, Theme B1 is a distinct counterpart to the opening theme. As depicted in Example 5, brackets above the staff show a two-measure basic idea (bi), a transposed restatement (bi’), and a four-measure continuation over the dominant. Although the harmonic rhythm supports the phrase structure, the melody exhibits subtle discord. Slurs in the right hand show a melody slightly displaced from the harmony, as though it were spilling over the phrase boundaries. Yet rather than being disconcerting, the incongruity reinforces the theme’s continuity—the melody wants to simply keep going. This is not unlike the opening of the A section, where the music seems to “get stuck” for the first three measures of each four-measure phrase.

I use this time in class to encourage further exploration into the theme’s melodic/harmonic tensions. We begin by conducting the hypermeter in two ways: (1) a quadruple hypermeter that conforms to the melody, with the first hyperdownbeat at m. 41; and (2) a quadruple hypermeter that mirrors the harmony, treating m. 41 as an anacrusis on beat four and thus arriving on tonic (m. 42) with a hyperdownbeat. I then play the passage a few more times, giving students the opportunity to conduct both patterns multiple times. This either/or scenario facilitates lively discussions on the importance of harmony versus melody in determining phrase boundaries, and also gives students the opportunity to consider the simultaneity of multiple “correct” interpretations.

Another interesting feature of Theme B1 is its harmonic structure. Although the tonic triad appears just three times in sixteen measures, the theme highlights E major in a broader manner, as illustrated by the harmonic analysis in Example 5. The first two measures of the phrase, bi, remain in tonic, E major; bi’ tonicizes the mediant, G♯ minor. Finally, the four-measure continuation tonicizes the dominant, B major. The theme’s second statement (mm. 49–56) follows a similar pattern, with the final measure breaking free to cadence in E major. Thus, although Theme B1 spends little time overtly expressing this new key of E major, it pays homage to it by tonicizing each member of the tonic triad in turn. A brief in-class harmonic analysis of mm. 41–48 first and foremost reinforces students’ understanding of applied harmonies, including an applied dominant of iii (m. 43) and an applied predominant and dominant of V (m. 45). I usually follow that up with a leading question: “Do you find the tonicization of iii to be significant or curious?” Many students mention the sequential nature of the passage, with melody and harmony alike rising by thirds, and consider the tonicization of iii simply a byproduct of this state of affairs. Some students, who are emboldened by the success of our F♭ tracing journey, connect the music’s tonicization of G♯ back to the original key of A♭. And others still will light upon the music’s large-scale expression of the E-major triad. Any and all of these interpretations are valid and arguable: I am not looking for a single correct answer here, per se, but rather to allow the class to ponder several possible analytical viewpoints.

Example 6. Theme B2, mm. 57–64. The dashed slurs highlight the E4’s near-constant presence throughout the passage.

As we approach the last few measures of the piece in class, and with the importance of F♭/E♮ firmly in the foreground of students’ minds, I have to do very little prompting to secure a focused analysis of Theme B2. As shown in Example 6, the brief passage tonicizes B major, and within it a musical pun of sorts develops—one that plays upon the E♮’s new role as dissonant pedal. Unlike the flowing Theme B1, Theme B2 is almost etude-like, with scalar passages in the right hand repeated over block chords in the left. The tonicization of B major materializes through two harmonies: V7/V (which often occurs with a 4–3 suspension over the bass, stubbornly asserting B’s importance in the absence of tonic triads), and the occasional pedal ![]() . In fact, the right hand seems more concerned with the relative minor as its passagework repeatedly frames the G♯–D♯ dyad. The double entendre unfolds in the left hand and is highlighted in Example 6. Dashed slurs show a stubborn E4 that gives way to a D♯4 only for the pedal

. In fact, the right hand seems more concerned with the relative minor as its passagework repeatedly frames the G♯–D♯ dyad. The double entendre unfolds in the left hand and is highlighted in Example 6. Dashed slurs show a stubborn E4 that gives way to a D♯4 only for the pedal ![]() (mm. 58.3, 60.2, and 62.3) and for the final cadence. In class, students readily locate the omnipresent E4 and label its function. I often isolate the left hand here and have the class sing the E4 and its resolution as I play. The

(mm. 58.3, 60.2, and 62.3) and for the final cadence. In class, students readily locate the omnipresent E4 and label its function. I often isolate the left hand here and have the class sing the E4 and its resolution as I play. The ![]() –

–![]() motion is loaded, full of anticipation, and has a distinct feel. Yet thinking back to the first measure, the same exact pitches resolved in the same exact manner, to a very different effect. In m. 1, F♭4 appears as ♭

motion is loaded, full of anticipation, and has a distinct feel. Yet thinking back to the first measure, the same exact pitches resolved in the same exact manner, to a very different effect. In m. 1, F♭4 appears as ♭![]() ; on the next beat it resolves to

; on the next beat it resolves to ![]() . Now in Theme B2, the F♭–E♭ resolution has been reimagined as E♮–D♯, with the new dyad taking on a pointedly different character. A new key and tonal context reframe the pitches to play fresh roles. With their minds attuned to the tracing subject at hand, students recognize and relish this connection.

. Now in Theme B2, the F♭–E♭ resolution has been reimagined as E♮–D♯, with the new dyad taking on a pointedly different character. A new key and tonal context reframe the pitches to play fresh roles. With their minds attuned to the tracing subject at hand, students recognize and relish this connection.

Example 7. Transition from the B section to the A section, beginning at m. 77. The left hand’s E4 (circled) is respelled as an F♭ over the barline, connecting the two sections just as the tied A♭ and C♭ connected the A section to B.

Theme B1 returns once more, and as the music prepares to return to the piece’s opening, E♮ makes one final critical appearance. The left hand rearticulates E4 at m. 80.3b, after it has already been played by the right hand a beat earlier as part of the final cadence. As Example 7 shows, this E4 links the B and A sections. Tied over the bar line, it is reimagined once more as F♭(m. 81) and returns to its very first role: the borrowed pitch that completes a vii°7 in the key of A♭ major. And with this final transformation, F♭/E♮ has come full circle.

Final Considerations

In my experience, tracing has been an invaluable pedagogical tool. I have incorporated it successfully into a multitude of courses, including those within the four-semester core sequence as well as general music theory classes for non-majors. Students have consistently exhibited high levels of engagement and achievement when exploring such pieces as Robert Schumann’s “Ich grolle nicht,” Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, and Franz Liszt’s “Bist du!” What is more, tracing need not be relegated to Western classical repertoire—it can be used for analyses of contemporary, jazz, film, and popular music as well. Moreover, it need not be relegated to pitch or harmony—tracing rhythmic motives or even timbral changes can result in engaging analyses. Tracing encourages detailed, thorough analysis while also allowing students to create arguments rooted in their personal experience with the piece. By focusing on what they find striking and placing it in a narrative arc, students often uncover compelling connections in the music. Furthermore, tracing gives life to the analytical process—students can peruse a piece freely, following their chosen musical event and building context around it. Like agency and narrative, tracing is one more tool for music theory instructors to nudge their students toward developing meaningful analytical insights.

Notes

1. See Fred Everett Maus (1988, 56–73) for perhaps one of the most influential looks into musical narrative. Maus’s discourse on effectively utilizing technical music-theoretical language, alongside affective descriptors, opened the door for a new and, I would argue, more powerful way of talking about music.

2. On this point, Sly and I are much more in agreement. See his sample analysis of Chopin’s Mazurka in F minor, Op. 68, no. 4, which identifies D♭/C♯ as the musical agent and discusses how it influences and directs the music’s development. The D♭/C♯ agent is similar to the musical event I propose as an ideal tracing subject.

3. With its slower tempo and flowing melody, the E-major theme seems to harbor characteristics of the Polish kujawiak, another folk dance often associated with the mazur.

4. Chopin uses similar right-hand ties over the bar line in several other mazurkas (Op. 6, nos. 1 and 4; Op. 24, no. 1; Op. 33, nos. 2 and 4; Op. 67, no. 4; and Op. 68, no. 4; in Op. 30, no. 1, the left hand does not enter until beat 2; in Op. 50, no. 3, it does not enter until the second measure), but those are accompanied by a strong tonic announcement in the left hand on the first downbeat. Op. 17, no. 3 is unique in its combination of the downbeat-obscuring tie, along with an opening harmony that is clearly not tonic.

5. Rudolph Arnheim might consider these initial measures in terms of “the dynamics created by the deviation or divergence from a norm base” (Arnheim 1984, 297). He defines a norm base specifically as a tonal center; I might expand that notion here to include any clear declaration of a key. Of course, most will hear the opening harmony as distinctly dominant, but that is only after the briefest flicker of surprise that it is not, instead, a tonic triad. This slight deviation from expectation creates a dynamic energy that draws us toward tonic. See Arnheim (1984, 295–309).

6. Steve Larson and Leigh VanHandel identify “gravity” as the weakest of their four musical forces. The melodic pattern ![]() –

–![]() –

–![]() , as seen here in the melody, exhibits a gravity score of 1, indicating that it does experience musical gravity. I find this effect to be compounded by the 4–3 suspension and its resolution. See Larson and VanHandel (2005, 119–36).

, as seen here in the melody, exhibits a gravity score of 1, indicating that it does experience musical gravity. I find this effect to be compounded by the 4–3 suspension and its resolution. See Larson and VanHandel (2005, 119–36).

7. For influential work on markedness, see Robert S. Hatten (1994).

8. The absence of left-hand downbeats for nearly the entire passage is also quite striking, even suggesting a pending metric shift that never comes to fruition.

9. We were first introduced to C♭ in Theme A1, mm. 7.2 and 14.3, as part of an applied vii°7. Here it reappears as the fifth of the ♭VI6. Both occurrences suggest a hint of A♭ minor. Later in Theme B1, this connection grows even stronger when the music briefly tonicizes G♯ minor. This is somewhat of a “bonus” feature that I may explore with more advanced classes if time allows.

10. Brian Alegant and Donald McLean describe a similar process as “enlargement.” They focus on the temporal enlargement of a surface-area object. Although temporality does play some part in the Chopin—the B section of E major is, of course, a much longer manifestation than single harmonies or pitches in the A section, the focus is more on the changing roles of F♭/E♮. See Alegant and McLean (2001, 31–71).

References

Alegant, Brian and Donald McLean. 2001. “On the Nature of Enlargement.” Journal of Music Theory 45, no. 1 (Spring): 31–71.

Arnheim, Rudolph. 1984. “Perceptual Dynamics in Musical Expression.” The Musical Quarterly 70, no. 3 (Summer): 295–309.

BaileyShea, Matt. 2011. “Teaching Agency and Narrative Analysis: The Chopin Preludes in E Minor and E Major.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 25: 9–36.

Hatten, Robert S. 1994. Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Larson, Steve and Leigh VanHandel. 2005. “Measuring Musical Forces.” Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal 23, no. 2 (December): 119–36.

Maus, Fred Everett. 1988. “Music as Drama.” Music Theory Spectrum 10, no. 1 (Spring): 56–73.

Monahan, Seth. 2013. “Action and Agency Revisited.” Journal of Music Theory 57, no. 2 (Fall): 321–71.

Sly, Gordon. 2005. “Developing the Analytical Point of View: The Musical ‘Agent.’” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 19: 51–63.