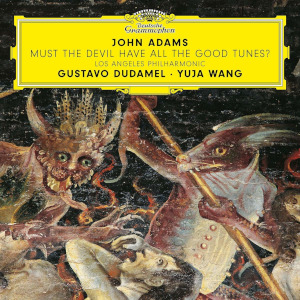

John Adams: Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? 2020. John Adams, composer; Yuja Wang, piano; Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo Dudamel, conductor. Deutsche Grammophon (DG) 00289 483 8289 7. Contents: Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes; China Gates. Digital Download, 4 tracks (30:59). Amazon, Google Play, and iTunes. $7.99.

John Adams: Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? 2020. John Adams, composer; Yuja Wang, piano; Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo Dudamel, conductor. Deutsche Grammophon (DG) 00289 483 8289 7. Contents: Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes; China Gates. Digital Download, 4 tracks (30:59). Amazon, Google Play, and iTunes. $7.99.

John Adams’s 2018 piano concerto Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? reaffirms his penchant for a memorable title. The name evokes a long history of hymnists borrowing melodies from secular music for insertion into sacred hymns. There is a devious playfulness in the depiction of a modern-day Erlkönig or the personification of death in Liszt’s Totentanz. Adams composed the concerto with the pianist Yuja Wang in mind. She premiered the work in the spring of 2019; this live recording captures her initial performances in the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. The album also features Adams’s China Gates (1977), which Wang played as a solo encore.

The piano concerto marks Adams’s fourth composition for piano and large ensemble, the others being Grand Pianola Music (1982), Eros Piano (1989), and Century Rolls (1997). These works highlight Adams’s compositional trajectory, moving from his earlier minimalist influences to denser contrapuntal textures and jazzier harmonies. His most recent compositions speak in an eclectic language where minimalism is just one of its basic components.

The concerto is structured in three movements without pause, utilizing the conventional fast-slow-fast format. In the opening movement, Adams transforms the sinister piano-guitar riff from Henry Mancini’s Peter Gunn from common time to mixed meter. Wang initiates this thematic idea and the orchestra follows, leading to a diabolical showdown. Dudamel captures the energy of this movement and the Philharmonic projects its force with poise. Wang coordinates a fine dance against a honky-tonk orchestral piano part that reinforces the solo pianist and occasionally punctuates chords in opposition to her leading role. She maneuvers the complex rhythmic language with precision, an impressive feat considering the bulk of her recording output explores early twentieth-century repertoire.

The second movement evokes an uncanny feeling of the devil at rest. Adams provides contrast to the opening movement, using the Phrygian mode to create an idyllic yet disturbed soundworld. Wang emphasizes lyricism here, but also finds a biting quality in her part. Dudamel achieves a perfect balance between the delicate piano and the accompanying orchestra; while Wang’s performance remains soft throughout, the orchestra never obscures her music.

The third movement presents a microcosm of Adams’s signature style in a fresh manner, with aural glimpses of Nixon in China (1987) and Hallelujah Junction (1998). For her part, Wang channels the brutale energy expressed in the music score, symbolizing the devil’s unleashed energy, which is thwarted at the close with sudden stops in the orchestra and piano.

As is customary with new works, the composer worked directly with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Dudamel, and Wang in preparation for the premiere. Accordingly, it is no surprise this recording showcases world-class musicians at their best. The Los Angeles Philharmonic is one of the leading orchestras in the world today. And no challenge seems too great for Wang, who Adams describes as having an “inexplicable command of the piano.” I hope the LA Phil continues this partnership with Adams and Wang for years to come.