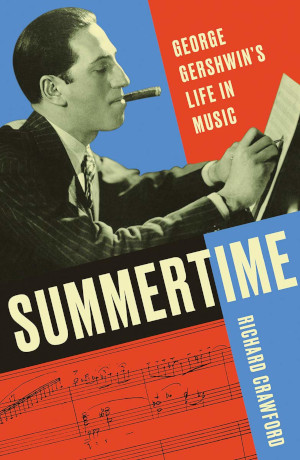

Summertime: George Gershwin’s Life in Music. Richard Crawford. New York: W. W. Norton, 2019. 594 pp. 17 b&w images. ISBN: 9780393052152. $39.95.

Summertime: George Gershwin’s Life in Music. Richard Crawford. New York: W. W. Norton, 2019. 594 pp. 17 b&w images. ISBN: 9780393052152. $39.95.

Isaac Goldberg published his George Gershwin biography in 1931, only seven years after the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue. Since then, writers like Merle Armitage, Edward Jablonski, and Deena Rosenberg have contributed to a steadily growing pile of Gershwin monographs. In 2006, Howard Pollack released the longest and most meticulously detailed Gershwin biography to date. Summertime, Richard Crawford’s attempt at this microgenre, presents the story of Gershwin’s life and music in a more condensed and inviting package than Pollack’s tome. He considers the composer’s songs, stage works, and concert-hall music while also investigating the professional and social milieu Gershwin navigated and his life-long educational quest, all to produce art that appealed to a diverse array of listeners.

Crawford closely follows a chronological scheme as he details Gershwin’s life from his Brooklyn boyhood to his death in Los Angeles in 1937. He divides the book into thirty-eight chapters, which together comprise nearly five-hundred pages. The first part covers Gershwin’s youth, his shift in career trajectory from professional pianist to composer, and his rise to commercial success and popular renown as a songwriter for George White’s Scandals and the author of “Swanee” (1919) and Rhapsody in Blue (1924). In the second part, Crawford explores Gershwin’s mid-career, including symphonic works, like the Piano Concerto in F (1925) and An American in Paris (1928), and hit Broadway musicals, like Girl Crazy (1930) and Of Thee I Sing (1931). The author also considers Gershwin’s London shows and his less successful works like the Second Rhapsody (1931) and Let ‘Em Eat Cake (1933). The final part discusses the composition, rehearsals, and production of the folk opera Porgy and Bess (1935), followed by Gershwin’s final months writing music for the Hollywood films Shall We Dance, Damsel in Distress (both 1937), and The Goldwyn Follies (1938).

Crawford dedicates appropriate weight to each of the songs, shows, and concert-hall works he selects to consider at greater length. With each of the stage shows, he summarizes the story act by act and pauses to detail the more well-known songs encountered therein. He also includes short biographies of Gershwin’s star performers, such as Fred and Adele Astaire, Ethel Merman, Anne Brown, and Todd Duncan. By far, Crawford allots the greatest amount of space to discussion of Porgy and Bess: six chapters, almost seventy pages total. The only musical examples are the Rhapsody in Blue themes and the melody to “Love is Here to Stay.” Perhaps Crawford should have also included examples of themes from the Concerto in F, as this piece is recorded frequently and it features regularly in symphony orchestra programs, though certainly not as often as the Rhapsody. Nevertheless, throughout the book, Crawford writes neat and lucid descriptions of themes, textures, and other musical elements. The non-musician reader will find his style approachable, attractive, and largely devoid of theoretical jargon.

Summertime is finely researched and full of interesting, relevant, and often lengthy quotations from first-hand accounts. In addition to insight from early Gershwin biographers, like Goldberg and Merle Armitage, Crawford draws upon reviews of Gershwin’s music and concert appearances; correspondence with family, friends, and business partners; as well as published commentary from Gershwin colleagues, like Fred Astaire, pianist Oscar Levant, and playwright S.N. Behrman. The selected reviews provide a balanced assortment of contemporary criticism. The author often turns from Gershwin’s professional career to focus on particulars of his private life. In such cases, Crawford allows the subjects to speak for themselves through long quotations from letters with friends and associates. He reports on Gershwin’s interest in psychoanalysis and includes some correspondence with therapists. Crawford dedicates significant space to Gershwin’s love life, especially his long relationship with composer Kay Swift. Levant, a close friend and top interpreter of Gershwin’s piano music, comes in as a narrative voice in the last chapter. Here, as other biographers have done, Crawford incorporates Levant’s account (1940) of Gershwin’s mental decline. Crawford’s discussion of Levant contains some inaccuracies. For example, he incorrectly states that Levant recorded Rhapsody in Blue with Frank Black’s Orchestra in 1925. The correct date, according to Ross Laird (2001), is 2 December 1927. The slip is inconsequential and understandable, since the wrong date comes from Levant himself. In all, Crawford well controls the pace of his narrative, relies on excellent resources, introduces first-hand accounts at appropriate moments, and allocates them a suitable amount of space.

Concerning Gershwin’s musical education, Crawford discusses at length three of the composer’s music teachers: Charles Hambitzer, Edward Kilenyi, and Rubin Goldmark. He leaves out Gershwin’s lessons with Henry Cowell. He mentions Joseph Schillinger only in passing, and does not discuss Gershwin’s application of Schillinger’s lessons to works like “I Got Rhythm” Variations (1933-34) and Porgy and Bess. I disagree with Crawford’s assertion that Gershwin began his piano studies in 1912. In an early interview (Billboard, 1920, p. 26), the composer said he began lessons at the age of fourteen. Relying on this statement, Crawford thus cites 1912 as the year the Gershwins purchased the family piano. However, Gershwin’s reported comments on his early education often conflict. In a later interview with Edward Cushing (1924) Gershwin’s story changed. He claimed: “I started out to be a pianist [...] taking my first lessons at the age of twelve and a half years. My memory is good on that point.” Finally, Howard Pollack (2006) has estimated convincingly that Rose and Morris Gershwin purchased the piano in late 1910, when Gershwin would have been twelve.

Despite these criticisms, Crawford has furnished an up-to-date, well-researched, and nearly complete investigation of this American composer’s life and artistic output. Crawford succeeds in demonstrating Gershwin’s cultural impact in both the classical and popular spheres and his appeal to audiences within and without the United States, although he does not extend his investigation beyond the composer’s lifetime. His relaxed prose, effective incorporation of contemporary criticism and correspondence, and concise and largely jargon-free descriptions of the musical material would appeal to the unfamiliar reader. This book would serve well as a text for an undergraduate-level course on Gershwin.

References

“Melody the Thing: Young Composer Declares.” 1920. Billboard. 13 March, pp. 26 and 33.

Cushing, Edward. 1924. “George Gershwin - Brooklyn Boy Composer.” Sunday Eagle Magazine. 18 May, p. 2.

Laird, Ross. 2001. Brunswick Records: A Discography of Recordings, 1916-1931. Volume 2: New York Sessions, 1927-1931. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Levant, Oscar. 1940. A Smattering of Ignorance. New York: Doubleday.

Pollack, Howard. 2006. George Gershwin: His Life and Work. Berkeley: University of California Press.