Introduction

In Part I of this essay, I identified six key qualifications, other than an earned doctorate, found in 25 tenure-track applied music faculty vacancy announcements: 1. teaching; 2. artistic/scholarly work; 3. career development; 4. recruiting; 5. service/governance; 6. diversity/inclusion. Next, I highlighted discrepancies between those qualifications and the competencies addressed by mandatory DMA coursework at 14 prominent music schools in the United States. Here, in Part II, I chronicle pathways for music schools to strengthen DMA candidate professional qualifications via upgrades to doctoral curricula and advising, and then I conclude with a framework for implementing change.

Strengthening DMA Candidate Professional Qualifications: Curriculum

First, let’s acknowledge that doctoral curricula are rigorous, and there isn't room to add courses without removing others. If improving candidate expertise and job-readiness necessitates adding courses, what can we cut? Given that DMA candidates take numerous music history and theory courses before embarking on doctoral studies, I submit that schools can reasonably cut six semester credits of required music theory and/or history electives (not the fundamental courses tied to qualifying exams). I suggest replacing those electives, in most cases, with three compulsory two-credit courses that delve into the following professional studies themes such that, upon graduation, candidates will have built up all six of the aforementioned qualifications:

- Music Career Development

- Faculty Career Development

- Music Pedagogy

In the ensuing paragraphs, I outline the content of those three proposed two-credit courses, each of which would meld academic study, writing, and practical application.

1. Music Career Development Course

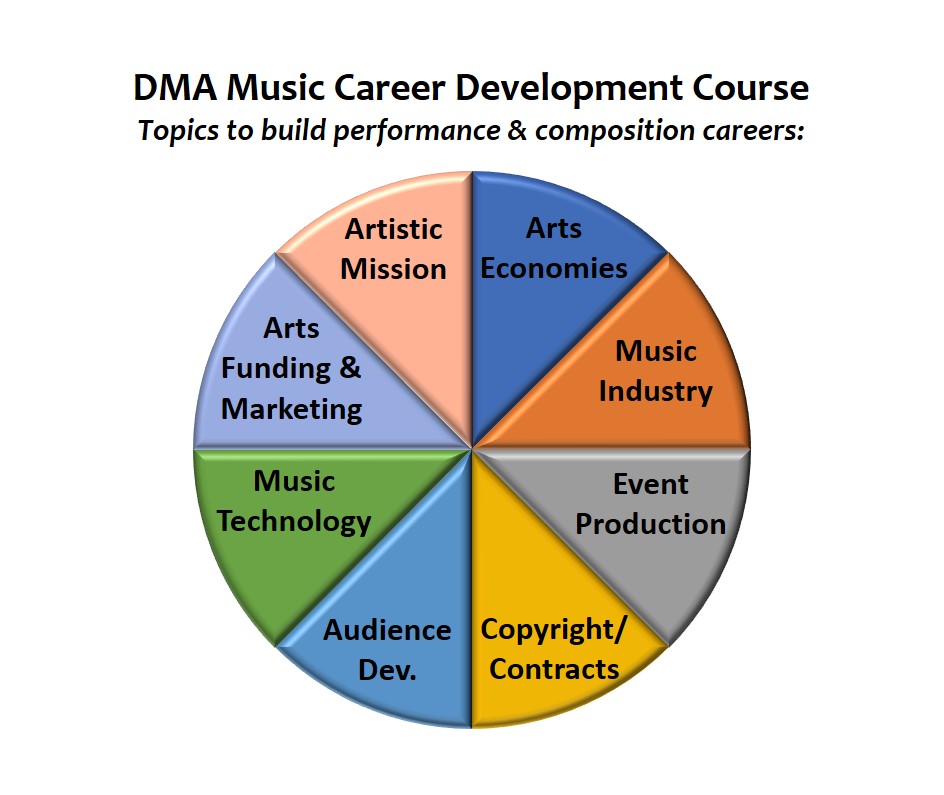

Prior to entering graduate school, music students characteristically undergo extensive training to perform in large ensembles; therefore, the doctoral-level music career development course I recommend would empower candidates to cultivate entrepreneurial performance and composition careers apart from the large-ensemble profession and also outside of academia. Chart 3 shows opportune topics to study and apply (Charts 1 and 2 appear in Part I).

Chart 3: Proposed topics for a DMA-level music career development course

Regarding ways in which course subjects could be applied, after articulating their Artistic Missions and discerning features of Arts Economies and the Music Industry, including matters of music publishing and licensing, students could harness principles of Arts Funding by working in teams to write real or mock grant proposals consistent with their missions. Audience Development, Event Production, and Arts Marketing concepts can similarly be fleshed out by teams examining research from the NEA, the Wallace Foundation, and others, and then arranging mock concerts designed to attract diverse audiences. Students could accrue insight into Copyright and Contracts through studying case examples and carrying out simulated commissioning ventures. Music Technology projects could center on students recording, editing, and mastering their own high-quality audio and video recordings, further intersecting questions of copyright law while supporting students’ needs to publish recordings and to self-produce video content for job applications and portfolio websites.

Notwithstanding the exact topics covered, upon finishing this course, which would ideally take place during the initial semester of study, students will have gained understanding of relevant music business practices, acquired a mix of career competencies, plotted trajectories for their artistic careers (possibly combining entrepreneurial activity with large ensemble performance), and delineated plans to accomplish noteworthy professional projects before graduation so that, when they set foot in the academic job market, they will demonstrate to university employers ample artistic achievements and potential (qualifications 2 and 3).

2. Faculty Career Development Course

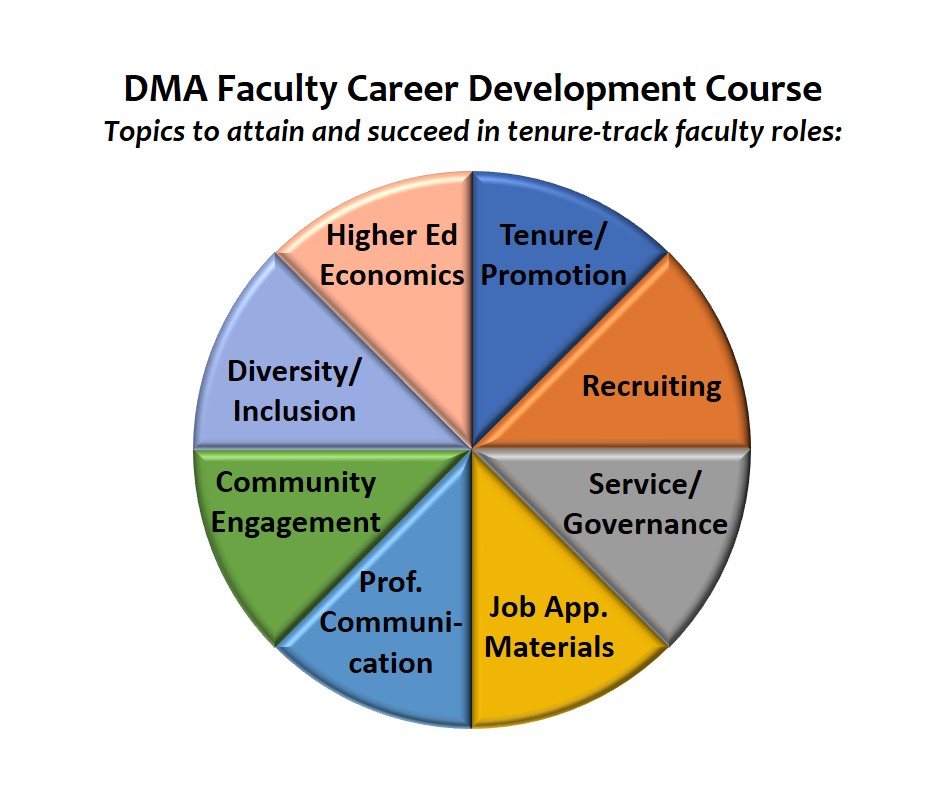

The faculty career development course I envision would be scheduled in the second semester of doctoral study and probe topics crucial to securing and succeeding in tenure-track faculty positions, as well as contributing to academic and non-academic communities (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Proposed topics for a DMA-level faculty career development course

Job Application Materials would be drafted by candidates in consultation with career advising staff (Chart 7) and then be refined and graded in this course. In tandem, the Professional Communication component would zero in on writing and presentation techniques and familiarize students with vital customs, among them, how to chair, listen, and speak effectively in committee meetings. By scrutinizing and formulating Recruiting Strategies, DMA candidates arm themselves to build enrollment in future teaching studios. Through the study of Higher Education Economics, Tenure and Promotion Practices, Diversity and Inclusion, Service and Governance, and Community Engagement, candidates can amass awareness, realize pertinent projects, and pilot their academic careers accordingly.

When this course concludes, students will grasp the inner workings of higher education institutions, possess polished faculty job application materials, and have documented plans to gain ongoing experience with student recruitment, service and governance, and diversity and inclusion (qualifications 4, 5, and 6).

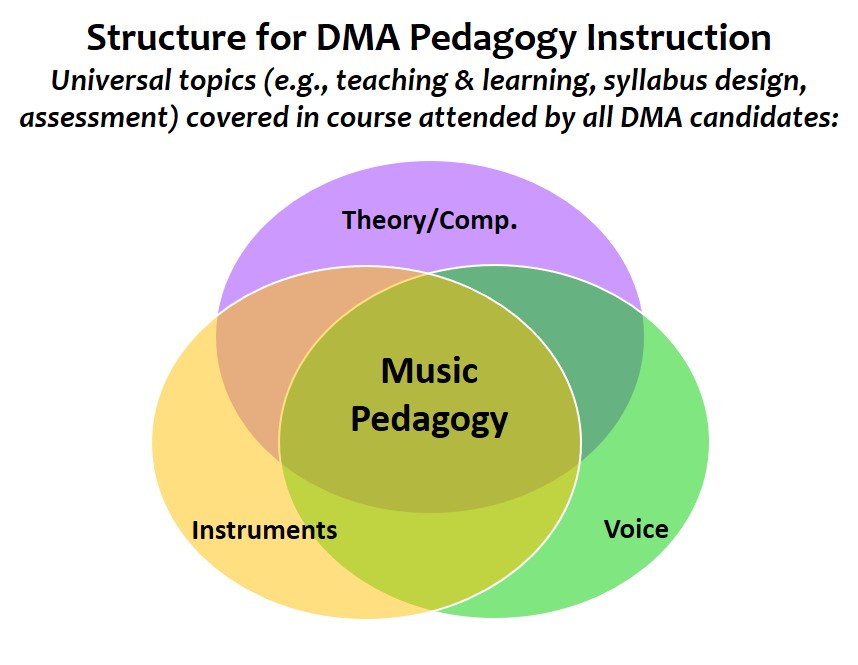

3. Music Pedagogy Course

Rather than scheduling wholly separate pedagogy classes for singers, instrumentalists, and composers, universal pedagogy topics can be tackled efficiently in a course attended by all DMA students. Candidates would investigate principles of teaching, learning, inclusion, and occupational health, and then devise syllabi, lesson plans, and assessments in line with their specialties. Textbooks could include:

- Bruce Mackh, Higher Education by Design (Routledge, 2018).

- Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel, Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Harvard, 2014).

- Gerald Klickstein, The Musician’s Way: A Guide to Practice, Performance, and Wellness (Oxford, 2009).

- Robert A. Duke, Intelligent Music Teaching (self-published, 2005).

Candidates would enroll in such a course no later than the fall semester of their second year of study. At course completion, they would be conversant with evidence-based pedagogy concepts and have in hand updated teaching philosophy statements accompanied by thorough designs for teaching and assessing undergraduate lessons and studio classes; some might also map out academic classes (e.g., Music Theory I). To sift through the particulars of vocal, instrumental, or theory/composition pedagogy, candidates could do research projects, organize colloquia, and/or take on internships or assistantships. Some departments might provide domain-specific pedagogy seminars and electives (Chart 5).

Chart 5: Proposed structure for DMA-level pedagogy instruction

Additionally, all DMA candidates should engage in part-time teaching while earning their degrees so that they apply pedagogical best practices and build track records of instructing and recruiting diverse students (qualifications 1, 4, and 6). But for many candidates to secure part-time teaching work—whether on or off campus, online or in person, or at college or pre-college levels—skillful advising is essential.

Strengthening DMA Candidate Professional Qualifications: Advising

I encourage schools to revamp both academic and career advising for doctoral candidates.

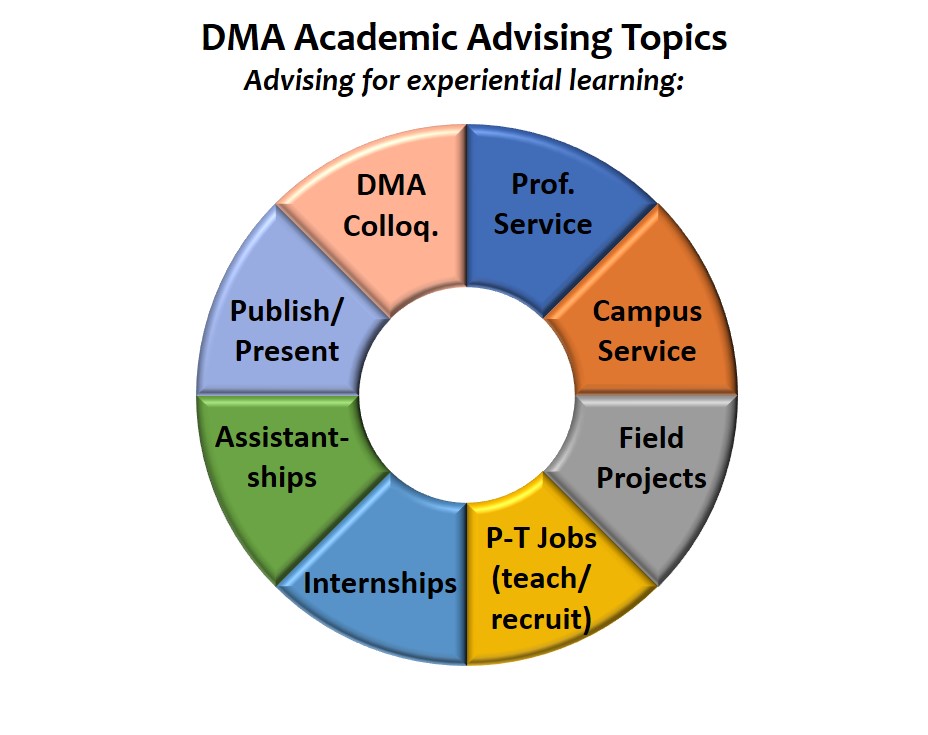

1. Academic Advising

Along with doing the important work of ensuring on-time graduation, enforcing academic policies, and the like, I suggest that doctoral academic advisors should also guide DMA candidates to access experiential learning opportunities that apply coursework and fortify candidate qualifications. For example, knowledgeable advisors can assist candidates to obtain governance and other valuable experience through campus service and participation in professional associations; they can prompt candidates to present at doctoral colloquia and refereed conferences and also publish in peer-reviewed journals. In collaboration with career advising staff, they can steer candidates to pursue internships, assistantships, and field projects, as well as part-time teaching jobs (Chart 6).

Chart 6: Representative DMA candidate experiential learning activities to be overseen by academic advisors

2. Career Advising

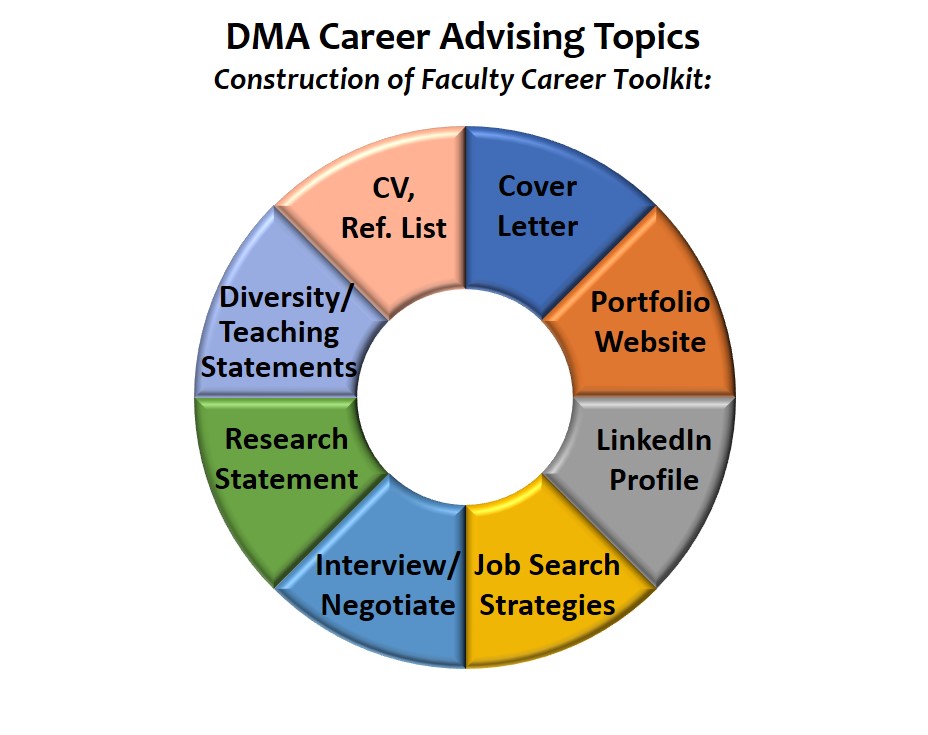

I maintain that the fundamental aims of DMA career advising should be for every candidate to:

- Craft the documents needed to apply for university faculty positions; i.e., an adaptable CV, cover letter, and reference list, plus teaching, research, and diversity statements.

- Publish a respectable LinkedIn profile and a comprehensive portfolio website.

- Acquire job search, interview, and negotiation skills.

In total, those materials and competencies form what I call a Faculty Career Toolkit (Chart 7). Staff at university and conservatory career centers can counsel DMA candidates in all of the toolkit elements. And because DMA-granting universities in the U.S. normally fund centralized career centers that support graduate students, career advising services are readily available to the great majority of DMA candidates, albeit some advisors may benefit from training in the idiosyncrasies of music higher education careers.

Chart 7: Components of a DMA candidate Faculty Career Toolkit to be overseen by career advisors

Implementing Change

1. Quality Enhancement

To renovate DMA programs, I propose that schools undertake the following steps, once a core group of stakeholders concurs that upgrading is needed:

- Convene a committee, comprised of faculty, leadership, alumni, doctoral students, and advising staff, to hammer out a Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) and spearhead its implementation.

- Survey DMA graduates from the past 10-15 years to determine their career outcomes, annual earnings, education debt, educational satisfaction, and ideas for program enhancement.

- Based on survey findings, committee member input, and institutional research and resources, draft a provisional QEP; gather feedback from stakeholders, and then amend the QEP to arrive at a final version.

- With a formal QEP prepared, obtain official faculty approval, institutional support, and funding for implementation.

- Once backing is in place, carry out curricular changes; arrange for any faculty and advisor training, hiring, or reassignment; weigh options for remote online instruction and advising.

- Wrap up hiring and training; finalize course content, syllabi, and schedules; create tools to assess courses, advising, and employment outcomes; ensure quality.

- Publicize the new DMA program; enroll a fresh class of candidates.

- Launch the program, retain records, track alumni, and then publish your data on the formation, implementation, and outcomes of your refurbished program.

2. Final Thoughts

The program enhancements that I describe here, when well executed, will equip DMA graduates with crucial qualifications, but faculty employment outlooks are clouded by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the impending drop in the college-age population (Grawe 2018). Although the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that post-secondary teaching employment will grow by 9% from 2019 through 2029 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), it’s unclear whether the demand for tenure-track applied music faculty will increase. I don’t find reasons to expect a substantial rise in the number of positions; it’s plausible that the number will decrease.

DMA-granting institutions, therefore, would do well to explore ways for their programs to prepare graduates to thrive in a range of professions, especially ones with favorable employment outlooks. For example, along with grooming doctoral candidates for faculty roles, schools might devise curricular and internship tracks for interested students to qualify for careers in higher education administration, church music, or other fields, recognizing that some DMA graduates will not attain full-time faculty jobs and few will sustain themselves via entrepreneurial activity alone; nearly all will depend on employment (see data on alumni outcomes on the website of the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project).

Ultimately, the future of music higher education will rest in the hands of the doctoral students we educate. Let’s embrace the innovations that will produce graduates poised to lead.

References

Grawe, Nathan. 2018. Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP). Accessed October 17, 2020. https://snaap.indiana.edu/.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. “Occupational Outlook Handbook.” Accessed October 17, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/education-training-and-library/postsecondary-teachers.htm.