Abstract

Executive leadership in music departments and schools is central to influencing the work environment and perspectives of music faculty. Survey responses of a national sample of ranked music professors (N=1,345) were analyzed to examine the relationship between faculty perceptions of leaders and faculty work perspectives. We ran a series of multiple regressions to understand the relationships between faculty work dimensions and their perceptions of leaders utilizing the Positive Leadership Model (PL): work climate, communication, relationships, and meaning. Quantitative analysis shows that music faculty who participate in vision setting, curriculum development, and budget planning view their leaders in a positive light in all four PL dimensions. A fair, consistent, and balanced evaluation system is also associated with all areas of Positive Leadership. In response to an open-ended question to describe ideal work conditions, music professors expressed their concerns, specifically about leadership, funding, balanced workload, tenure and promotion, communication and transparency, professional development, and institutional goals and values. These comments were analyzed for their content and put into the four PL frames. A new nomenclature emerged from the data—structure, indicating that music professors looked beyond the PL model. In a word, they pointed to the academic structure that hampers their work perspective and optimistic view of executive leadership.

Vincent Benitez

Introduction

Leaders in organizations matter. A recent Gallup poll of 7,200 US workers cites that more than half of the adults surveyed claimed to have left a job because of a boss (Weber, 2015). Rigoni & Nelson (2016) reported that two-thirds of employees are unclear about what is expected of them, nor do they engage in the setting of their own role expectations. These studies point to the critical role that leadership plays in how long workers stay in an organization and a leader’s impact on how effectively workers are engaged in the shaping of their place of employment.

Academic leaders are agents for change, playing critical roles in shaping unit culture within their institution (Knight & Trowler, 2001). Deans and chairpersons are the leaders of academic units, such as departments, schools, and colleges. Their most important responsibilities include goal setting, faculty hiring and evaluation, curricular development, and unit rejuvenation (Nelsen, 1981). Research confirms that leadership and work environment are the two most salient factors that affect faculty work and their sense of vitality (Baldwin, 1990; Lee,1995). These researchers also addressed renewal (an individual faculty member’s ability to return to the vital state in the face of a plateau or work blockage) as an essential part of faculty work-life. Baldwin (1983) emphasizes that while faculty are accountable for their professional renewal efforts, leaders can be “catalytic rather than judgmental” in their supportive role in the renewal process.

Literature

The literature on faculty work and vitality shows evidence that academic leadership influences faculty growth (Blackburn et al., 1991), the overall aspects of faculty vitality (Baldwin, 1990), research quality (Bare, 1980), collaboration, goal setting, and individual perspectives (Creswell & Brown, 1992). Chairpersons can enhance faculty growth and performance by acting as negotiators or protectors (Zey-Ferrell & Baker, 1984), providers, enablers, advocates, mentors, encouragers, collaborators, and challengers (Creswell & Brown, 1992). The academic leader as the provider and enabler assumes an administrative role by supporting funding, staff, and visibility. The advocate deals with external functions, such as lobbying for resources, facilitating interaction, and assisting politically. By role modeling, sharing experiences, critiquing and reviewing, the mentor assumes a more interpersonal role. The encourager, also an interpersonal functionary, provides general moral support, recognition and appreciation, and task-specific encouragement. Sometimes, the leader works with faculty on a project as a collaborator and, in other cases, helps through joint goal-setting for a project. The challenger inspires, evaluates, and monitors faculty research. Creswell and Brown (1992) further note that maintaining good interpersonal relations seems to be more important than any other good relationship characterizations. Furthermore, they observe that chairs use interpersonal strategies with senior faculty members and assume administrative roles with junior faculty.

Researchers in the arts academy have also learned that successful and productive artists and researchers thrive under positive and supportive leadership (Risenhoover, 1972; LeBlanc & McCrary, 1990; Jones, 1986; Murnigham & Conlon, 1991). Cowden and Klotman (1991) underscored good interpersonal relations as among the desired music leadership characteristics, especially working with people and communicating well with staff and faculty. They noted enthusiasm for work, remaining calm under pressure, and sustained energy and vitality to be fundamental to academic music leadership. Leadership characteristics go further: for example, enjoying diversity in the workplace; cooperative, empathetic, and non-competitive behavior; and motivating and fostering teamwork are critical for successful leadership. Grant (1992) suggested that music administrators must make a personal commitment to help new faculty members by communicating with each one of them regarding their needs and expectations. The academic leader should establish, therefore, a supportive work environment, look for and reinforce tangible signs of success, and empower faculty leaders to probe relevant issues and pursue dialogue and solutions.

Music departments pose particular problems, since faculty roles are diverse and specific—a recent College Music Society directory (2018) lists 26 job categories and 164 specialties. The multidimensional mission of the artists and scholars in today’s music faculty requires more proficient and insightful leaders than other disciplinary units in which scholarship outcomes yield academic publications. Despite the manifold demand required of music leadership, there are few professional resources for the new music academic leader, as well as limited opportunities for ongoing leadership training (Aziz et al., 2005). Consequently, few faculty leaders are willing to take on the executive leadership responsibility, have an opportunity to influence their colleagues, and shape departmental goals and trajectories. Even with the intricate relationship between a music faculty and its leader, most academic leadership studies tend to focus on leadership attributes and behaviors as they affect the organization. Few have examined leadership through the eyes of faculty pertinent to their work perspective and work environment. An analysis of the leadership perceived from the music faculty’s perspective can help understand, shape, and define the academic music leader.

Lee (1995) investigated relationships between departmental conditions and music faculty vitality with a 122-item questionnaire, which was designed to measure faculty perceptions of their sense of vitality within the organization. The study found that departmental conditions explained all dimensions of faculty vitality except for self-renewal. Among them, the executive leadership was one of the most salient contributors to predicting music faculty vitality, along with shared governance, career socialization, and working conditions. The study strongly suggests the need to understand academic music leadership, particularly through faculty perspective, and to help develop a training plan for future leaders with informed strategies.

Framing Leadership

Cameron’s theory on Positive Leadership (2012) provides a practical model to examine our theory-based leadership construct. The Positive Leadership (PL) concept takes a person-centered approach to study organizations (Buller, 2013; Cameron, 2012; Tummers et al., 2016). At the core of this work is the belief that Positive Leaders enable workers to achieve positive performance deviation, which is characterized by increased effectiveness, an ability to see opportunity embedded in problems, and a focus on virtuousness on the part of people and organizations.

There are four work dimensions identified in this enabling leadership model of practice; they are: (1) Climate, (2) Relationship, (3) Communication, and (4) Meaning.

Climate: The positive leader creates a climate that induces, displays, and interprets positive emotions among workers, affecting a sense of well-being and a cheerful outlook for the organization.

Relationship: A positive relationship enhances the human psychological capacity to experience broader and more intense emotions (Heaphy, 2007), allows resiliency in handling emotions (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003), fosters a sense of self-identity and efficacy (Roberts, 2007), and motivates commitment to the organization (Kahn, 2007). Leadership scholars have also examined biological factors: that when people experience positive relationships, their hormonal system is balanced (Ryff et al., 2001; Taylor, 2002); their cardiovascular system is strengthened (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2003); and their immune system is more efficient (Cohen et al., 1997; Heaphy & Dutton, 2008).

Communication: Cameron theorized that positive communication is the most critical predictor of organizational performance. In positive communication practice, the leader does not use negative statements such as criticism, disapproval, dissatisfaction, and cynicism. Instead, he uses statements that express appreciation, support, helpfulness, approval, or compliments.

Meaning: Wrzesniewski et al. (2003) have defined the way people regard their work via three tiers of meaning: as a job, a career, or a calling. A job denotes work that brings in financial reward; a career is a commitment motivated by accomplishment and success; while a calling involves a more profound sense of purpose beyond oneself and brings intrinsic satisfaction. In this theory, the ultimate Positive Leaders inspire workers to engage in their work for the value and virtue of the work itself, the impact it can have upon humanity, and the sense of community in the workplace.

The Study

We focused on the praxis of music leadership gauged by faculty perspectives on their work and work environment. From Lee’s 122-item psycho-sociometric survey, we selected 19 variables describing faculty work perspectives and nine leadership characteristics for the study.2Sociometry is a quantitative measurement of social distances and affinities among people, including patterns in friendships, social networks, work conditions, satisfaction, and support systems. Psychometry is a quantitative measurement of intelligence, personality, attitude, morale, and job satisfaction among many human psychological dynamics (Miller 1991).

Lee’s music faculty questionnaire (1995), derived from the synthesis of comprehensive faculty studies in higher education, was validated by two focus groups—each one comprising 24 music faculty members—from two major universities (University of Michigan and Eastern Michigan University). Cronbach’s alpha was used to test the reliability (departmental conditions alpha ranged from 75 to 97; faculty vitality range of 46 to 84) from a national random sample of 745 ranked music professors. The College Music Society’s Review Committee, charged by the Executive Director Robby Gunstream, evaluated the 1995 instrument for appropriateness and currency for the proposed 2015 Music Faculty Study (Taylor, 2014). The College Music Society compiles a complete roster of music faculty annually in all NASM certified music programs regardless of their institutional or individual affiliation with CMS. Historically, CMS has been supportive of professional research on faculty issues.

The consensus for an acceptable number for quantitative study in the social sciences is >500. For further discussion on sample size, see https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm or https://statisticsbyjim.com/hypothesis-testing/sample-size-power-analysis/

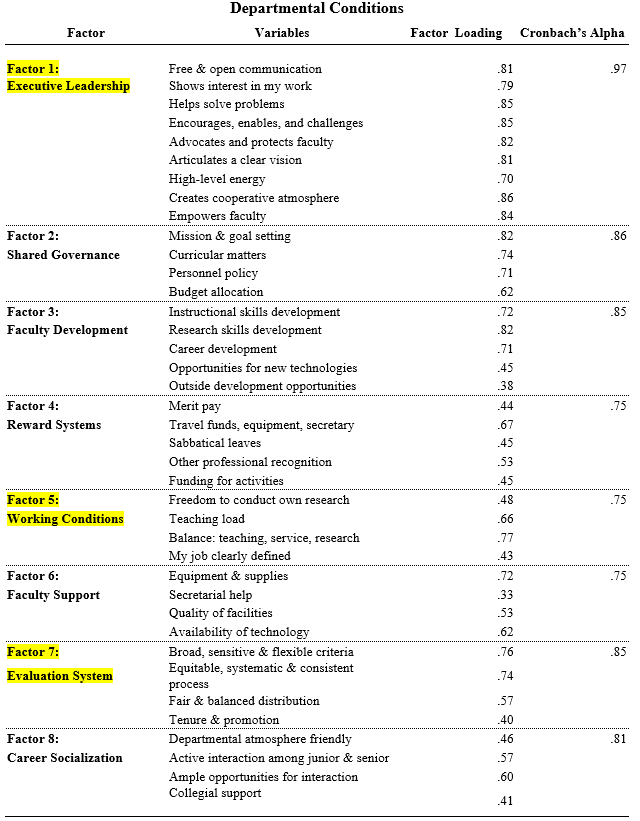

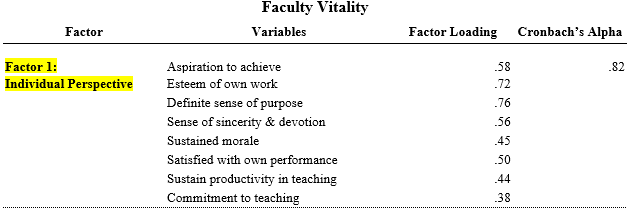

Research Model3Executive leadership and Faculty perspective variables are derived from factors in Lee (1995). Executive leadership was adopted from Factor 1 of Departmental Conditions (with nine-item factor loadings of .81, .79, .85, .85, .82, .81, .70, .86, .84 and Cronbach’s Alpha, .97; see the table below). We selected 19 faculty perspective variables from Departmental Conditions: (1) Factor 5-Working Conditions (with loadings .66, .77, Cronbach’s alpha .75); Factor 7-Evaluation System (factor loadings of .76, .57, and Cronbach’s alpha .85); and (3) Faculty Vitality, Factor 1- individual perspectives (with factor loadings .58, .72, .76, .56, .45, .50, .44, .38 and Cronbach’s alpha .82). (Please see additional tables in footnote section below.)

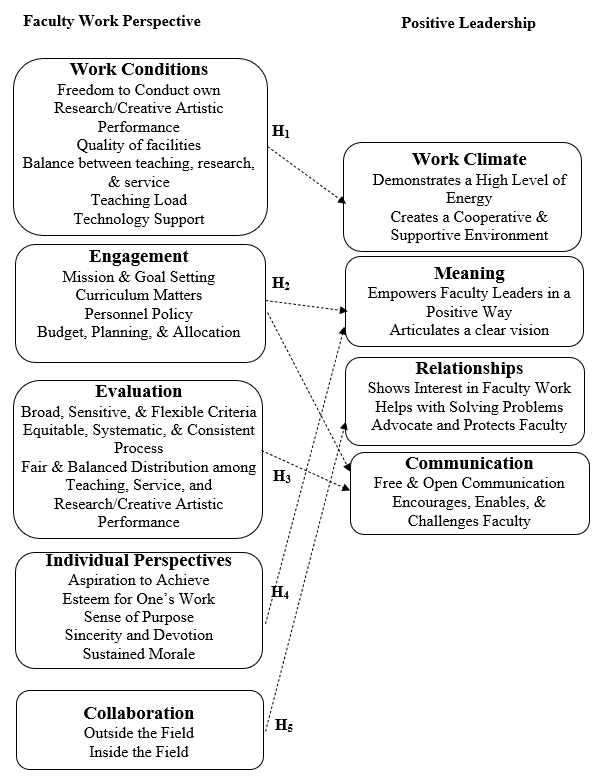

We framed faculty perspectives into five categories: (1) work conditions, (2) engagement, (3) evaluation, (4) individual perspectives, and (5) collaboration. Work conditions are operationalized by the freedom to conduct their research and creative activity, quality of facilities, workload, balanced workload among teaching, research, and service, and technology support. We measured engagement by the level of participation in vision setting, curriculum development, personnel decisions, budget planning, and role expectation. The evaluation included broad, consistent, and fair content, and balanced procedure. Individual perspectives are elucidated by aspirations to achieve, esteem for one’s work, a sense of purpose, sincerity and devotion, and sustained morale (Clark et al., 1985). Collaboration has two components: collaboration with colleagues outside one’s field and colleagues within the field. In music, perhaps more so than in other fields, faculty service and research are continually broadening to involve work within and outside their department.

The term executive leadership denotes the highest-ranking administrator of an academic music unit, such as a department chair, school director, or college dean. Executive leadership was measured by nine characteristics (Lee 1995): (1) demonstrates a high level of energy; (2) creates a cooperative and supportive environment; (3) empowers faculty leaders in a positive way; (4) articulates a clear vision; (5) shows interest in faculty work; (6) helps with solving problems; (7) advocates and protects faculty; (8) free and open communication; and (9) encourages, enables, and challenges faculty. We framed the nine variables into four Positive Leadership work dimensions (Cameron, 2012): (1) Work climate was related to “demonstrates high energy and creates a supportive environment”; (2) Meaning was identified with “empowers faculty and provides a clear vision”; (3) Relationships comprised “shows interest in my work, solves problems, and advocates for faculty”; and (4) Communication included “communicates effectively and encourages, enables, and challenges faculty.” Cross-referencing our literature-based leadership construct with the four practice-based dimensions helps determine our model’s conceptual efficacy vis-á-vis Cameron’s Grounded Theory.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework and hypothesized relationships between faculty perspectives and their leadership assessment. Hypotheses were established based on past literature to guide our data analysis: We expected positive associations between:

- Work conditions and work climate

- Faculty engagement with meaning and communication. This hypothesis is based on the notion that faculty who understand the purpose of the organization feel more meaningful about their work and leadership (Grant, 2012; Shanafelt, 2009), and that engagement leads to more effective communication (Vogelgesang et al., 2013).

- The evaluation system and communication. We theorize that a positive leader, who is also an academic peer, would establish good communication in their role as an evaluator.

- Individual perspectives and meaning

- Faculty collaboration and enhanced relationships.

Figure 1: Hypothesized relationship between faculty perspective and positive leadership

Methods

We applied the social-sciences approach to guide our conceptual model through Cameron’s Positive Leadership frame. We used multiple regression models to measure the relationships between the variables relating to faculty work perspectives and faculty ratings of the unit leadership. Responses to the open-ended question posed at the end of the questionnaire were content analyzed applying Hsieh and Shannon’s guidelines (2005), Corbin and Strauss’s three-step procedure (1998, 2008), and other well-regarded qualitative protocols (details below in the analysis section).

Data Collection

Our sample (n=1,345) consisted of the respondents from the survey distributed to all ranked music professors (n=12,401) listed in the 2014 College Music Society registry. This census included currently working ranked music professors at music departments and schools that offer NASM (National Association of Schools of Music)-approved music degree programs in the United States. CMS supported the study with email access to the national music faculty census. As a national society of music professors, CMS seeks to promote “music teaching and learning, musical creativity and expression, research and dialogue, and diversity and interdisciplinary interaction” (www.music.org). We limited the study population to ranked professors due to their role in the shared governance structure. We did not include annually reappointed adjunct artist faculty because they have limited shared governance participation. We shall examine this population’s work conditions, faculty perspective, and leadership issues in a future study.

Analysis

We analyzed four demographic, 19 faculty perspective, and nine leadership variables framed in four PL work dimensions, using descriptive and inferential statistics, followed by a qualitative content analysis of the responses from an open-ended question probing the thoughts of faculty members on an ideal situation that would foster their vitality.

Quantitative analysis: We applied a series of multiple regressions to examine the relationships between unit leadership perceptions and variables relating to faculty work perspectives. Multiple regression is appropriate for this analysis rather than causal or path models, given the cross-sectional nature of our data and the hypotheses we seek to inform. Regression also allows for robust analysis of multiple variables in relation to a specific outcome, while controlling other variables. Due to the lack of variability in the 5-point Likert-type scale, where most of the responses fell between “strongly or moderately positive” or “not positive,” the dichotomous category of variables is preferred to represent our data. Further, this model allows us “to put categorical variables[,] such as gender, social class, marital status, political preference, and the like, into a regression equation[,] if they are recorded as binary variables” (Ary et al., 1996).4Multiple classification, dummy variables, or nonparametric models are other analytical options. See https://www.xlstat.com/en/solutions/features/ordinary-least-squares-regression-ols.

Below we describe the series of demographic variables, faculty perspective variables, and leadership assessment variables:

Demographic variables. We included four personal and institutional characteristics: (1) gender, (2) faculty rank, (3) years of service, and (4) institutional control (i.e., private or public). These demographics are essential, given the potential impact institutional or professional experience might have on the respondent’s perception of leadership.

Independent variables: Faculty perspective. We classified 19 faculty perspective variables into five categories (see the Research Model above for descriptions and note no. 2 for factors from which the variables were drawn).

Dependent variables: Leadership variables. We framed the nine leadership characteristics into four PL work dimensions to interpret our data vis á vis the positive leadership concept, in order to focus on the significance and direction of the relationship latent in our data coefficients. We took this approach due to the number of variables we included in the model and for efficiency, given the number of PL leadership characteristics of interest: (1) PL work climate; (2) PL meaning; (3) PL positive relationships; and (4) PL communication.

Qualitative analysis: We utilized a qualitative content analysis following Hsieh and Shannon’s (2005) guidelines and Corbin and Strauss’s (1998, 2008) three-step approach to coding: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Qualitative responses to the question, “please describe the ideal conditions for your vitality,” elicited a wide, compelling, and rich variety of answers on the topic. We began the process by reviewing 100 of the total 427 responses at random to identify recurring themes (Morse & Richards, 2002; Patton, 2015). Seven salient themes emerged, which were confirmed by the remaining 327 responses. We then utilized NVivo data analysis software to help in constructing and storing the qualitative data (Hutchinson et al., 2010).

Results

Quantitative results

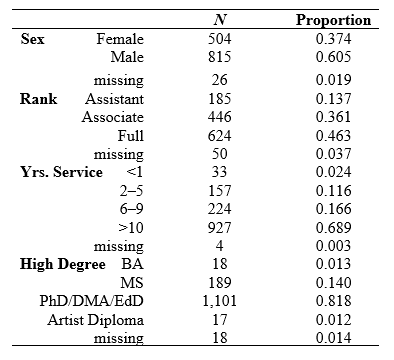

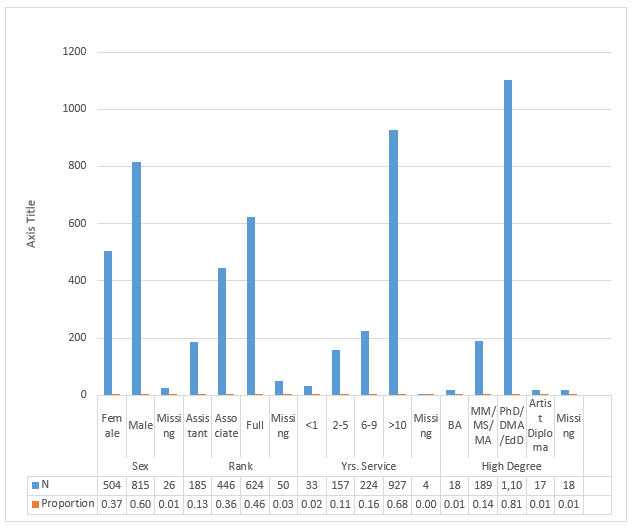

Description. Our data had a higher number of male respondents, commensurate with the population of ranked music professors across the country (38% female/62% male). Respondents tended to have achieved tenure and had more than six years of experience (85%) at their current institution, with over 81% having a terminal degree. As shown in Table 1, the largest number of respondents were full professors (46%), followed by associate professors (36%), and then assistant professors (14%). This strong participation of senior-ranking professors was unexpected. Graph 1 shows the same respondent description in graph form.

Table 1. Respondent description

Graph 1. Respondent description

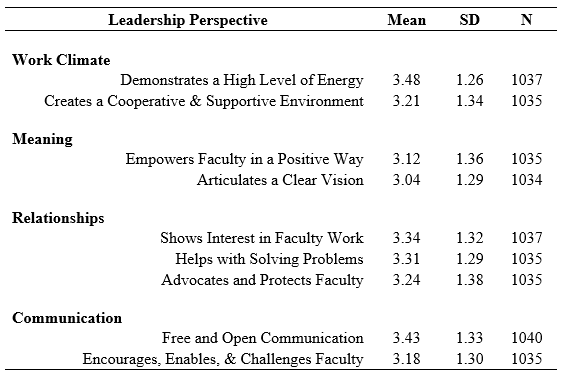

Table 2 provides the mean and standard deviation for the faculty ratings on leadership. It is clear that faculty perceive their leaders as average in all categories (ranging 3.03–3.48 in the scale of 5 as the highest), with a good amount of variance in their responses (SD 1.26–1.37). Beneficially, the qualitative content analysis (see below) gives distinction behind the numbers.

Table 2. Faculty ratings of Executive Leadership

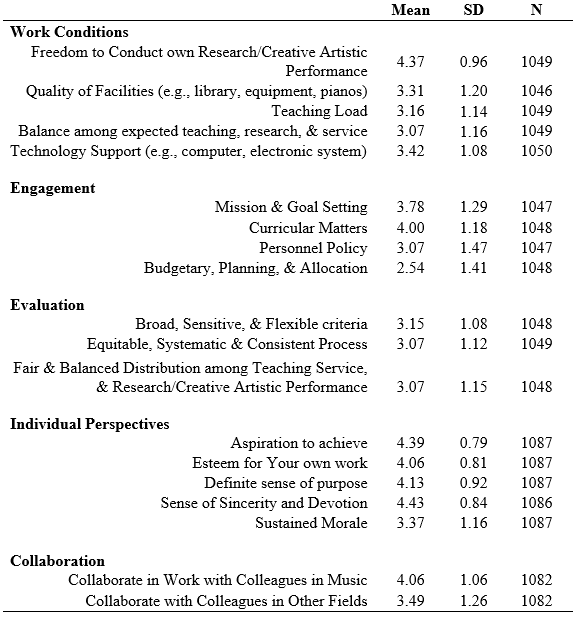

Table 3 shows the perspectives of music professors regarding their work conditions, engagement, evaluation, individual perspectives, and collaboration. Music professors enjoy the freedom to conduct their research and creative activity (4.37, SD .96) and moderate engagement in curriculum development (4.00, SD 1.18). At the same time, they rate engagement in goal settings, personnel and budgetary decisions, and evaluation variables with less enthusiasm (ranging from 2.54 to 3.78). Among individual perspectives, the highest rated are a sense of sincerity and devotion (4.43, SD .83) and high aspiration to achieve (4.39, SD .79). Relatively high scores are also found in the esteem of one’s work (4.06, SD .81), a definite sense of purpose (4.13, SD .92), and collaboration with colleagues in music (4.06, SD 1.06). We see lower scores in sustained morale (3.37, SD 1.16) and collaboration with colleagues outside the music field (3.49, SD 1.26).

Table 3. Faculty perspectives

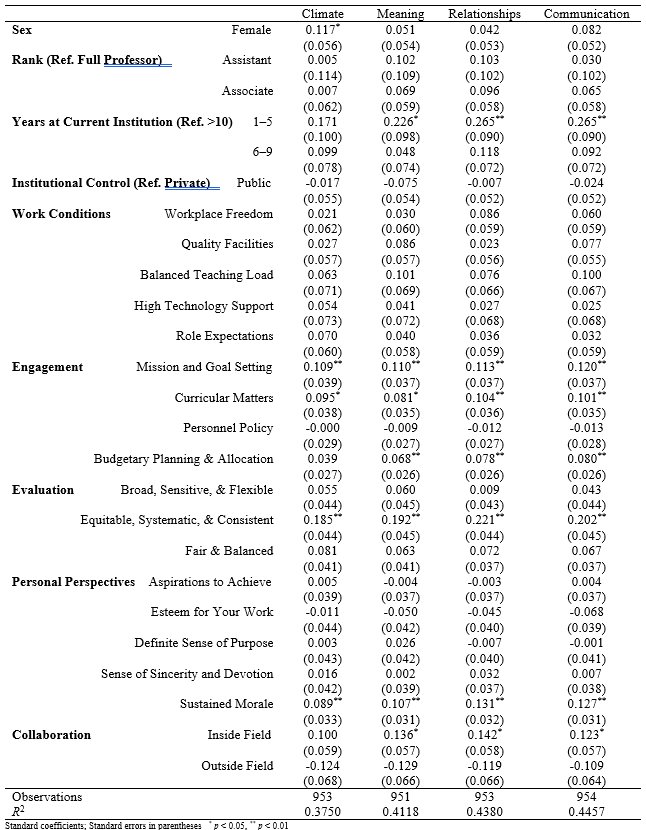

Multiple regression results. Table 4 presents the multiple regression models showing associations of faculty perspectives and four leadership components. Positive numbers in regression coefficients are associated with a positive perception of the academic leader’s ability to develop the specified area. Incidentally, we observe that women have a more positive perception of their leader’s ability to develop a positive work climate than men (p<.05). Newer faculty who have been in the current institution less than five years perceive their leaders to be more capable of developing communication and relationships (p<.01), and meaning (p<.05) than faculty who have been at the institution longer. We did not find any relationship between the institution’s control (e.g., public or private) and the faculty’s perception of their leaders.

Surprisingly, no relationship was found between any of the work condition variables and faculty views of their leadership. Among the engagement components, participation in the vision setting (p<.01) and curriculum development (p<.05) are predictors in all four leadership work dimensions. Involvement in budget planning has a positive relationship with the leader’s ability to foster meaning, relationships, and communication (p<.01), but not with setting climate. Among the evaluation variables set, equitable, systematic, and consistent were the only significant predictors relating to all four components of positive leadership. Among the individual perspectives, sustained morale demonstrates a positive association with all four leadership dimensions (p<.01). We find that collaboration with colleagues inside the music field is associated with a leader’s capability in fostering meaning, relationships, and communication (p<.05), but no relationship was found between outside-field collaboration and leadership.

Table 4. Multiple regression models: Faculty perspective and Positive Leadership (OLS Models)

Qualitative results

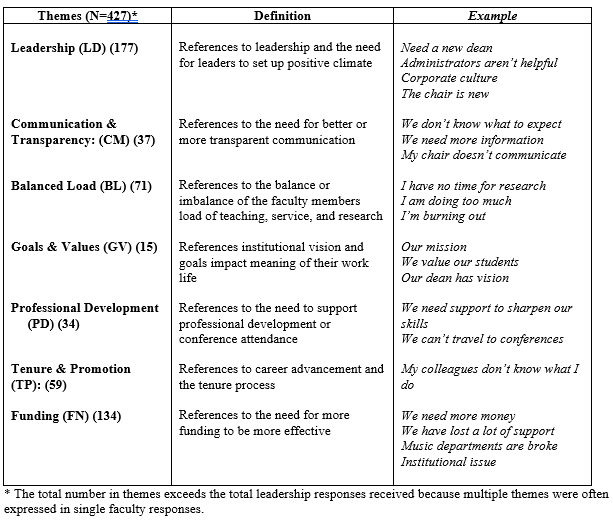

We received 427 responses (31.8%) on the open-ended question that invited expressions on the ideal organizational conditions that would foster greater vitality. Table 5 shows seven themes of concerns that emerged from the data: leadership, communication and transparency, balanced load, goals and values, professional development, tenure and promotion, and funding.

We received the most frequent comments on Leadership (177/427, 37.5%), with funding being the second prevalent concern (134/427, 28.3%). Professors voiced their concerns equally about balanced workload (71/427, 15%) and tenure and promotion (59/427, 12.5%); communication and transparency (37/427, 7.8%); professional development (34/427, 7.2%); and to a lesser extent, institutional goals and values (15/427, 3.2%). The total number of themes exceeded the total responses received because multiple themes were expressed in single faculty responses.

Table 5. Leadership analysis per identified codes, definition, examples, and frequency

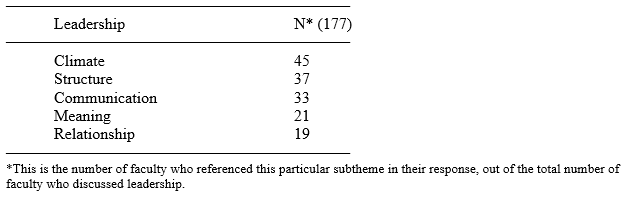

Utilizing a content analysis approach, we categorized themes into the four PL dimensions. An additional dimension highlighting the institutional structure emerged that fell outside of the theoretical framework, which indicated that the music faculty’s assessment of the leadership role extends to the milieu beyond the unit level. We named the new theme structure.5Grounded Theory was a new investigative qualitative method developed by American sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967) to describe a qualitative approach with no preconceived hypothesis that used continually comparative data analysis. The theory obtained by this method originates from the data. Creswell (2009) further articulated “a qualitative strategy of inquiry in which the researcher derives a general, abstract theory of process, action, or interaction grounded in the views of participants in a study” (p.12 & 229). Creswell continues: “[T]he primary characteristics of grounded theory research design [are]: 1) the constant comparison of data with emerging categories and, 2) theoretical sampling of different groups to maximize the similarities and differences of information” (p.13). Also see http://avantgarde-jing.blogspot.com/2010/03/grounded-theory.html#:~:text=According%20to%20Creswell%20(2009)%2C,a%20study.%E2%80%9D%20 and Johnson (2015).

Table 6. Sub-coded PL leadership

PL Dimensions Comments

Climate. Many commented on the importance of how leadership influences work climate, particularly alluding to a music administrator’s role in creating a corporate culture: “The corporate atmosphere breeds fear and resentment and secretiveness. . . . The best faculty are leaving through early retirement, moving to other institutions, even leaving the field, and the rest just hide out.” Another respondent was critical about the climate creating inequality and favoritism, but also recognized the inadequate psychological insight of the leader: “People want to be respected, valued. For some, this is achieved paradoxically through fostering inequalities: seeing oneself as more valuable than others and/or, when in a position of leadership, showing favoritism, both of which cut into the quality of life for others. . . . I like to think that awareness of this basic psychological factor could benefit many departments.” These comments represent the faculty’s concern about the lack of a positive climate and the need of leaders’ awareness of the primary psychological factor to create a positive climate.

Structure. An additional dimension of leadership, Structure emerged from many respondent comments. Although this is likely more connected to a macro vision of leadership (i.e., how departments, colleges, and universities are interconnected), this concern illustrates how faculty perceive the leadership structures around them as the major mechanism having effects on their work within the institutional structure. One faculty member described it this way: “The administrative structure of the College requires that Theatre, Dance and Music all have Directors that report to a Dean of the College. This is very ineffective and relegates the Directors to a lower status [than] they deserve. This structure needs to be revamped.”

This reaction was rather common. Many faculty argued further that resources have been devoted for supporting leadership staff, but they rarely see the benefit of those dollars. They worry that students are being burdened by the cost and that their educations are not being prioritized. These comments are one-sided, however; in actual fact, they signified a broader problem involving all four dimensions of Positive Leadership (climate, communication, relationship, and meaning), as well as the additional structural dimension.

Communication. Our respondents often commented on the lack of communication and transparency in the context of leadership. Respondents felt that they were in the dark or that their leaders were not providing them with the information that they needed: “Communication between faculty and upper-level administration needs to be open and honest; faculty have had no voice in decisions regarding canceling of courses, change of load computation, changes in benefits, removal of sabbatical opportunities.”

This call for a more open-and-honest dialogue added nuanced complexity, as some respondents felt that there might be inequity in the communication loop: “Administrative processes that are ambiguous or vague leave one with a sense of unfairness. To be told there isn't room to apply for promotion but hear the yearly promotions in other departments at fall faculty meetings creates the opposite of vitality.”

This idea of favoritism is revealed earlier in the “climate” discussion and emerges again with “communication” challenges, hinting that communication and climate are intrinsically linked.

Meaning. The survey participants commented on how an administrator’s vision affected their sense of purpose. For example, one faculty member said: “Our institution as a whole suffers from a general lack of vision and creativity in moving ahead under the current administration. There is too much reliance on past practice and an unwillingness to look comprehensively at the institution's strengths and weaknesses and therefore, to make hard decisions that could impact the future in a positive way.”

This comment illustrated that leaders with vision and creativity are what music faculty desire to increase meaning in their work life. Many respondents discussed how, in their opinion, administrators did not value the arts: “Things have changed over the last several decades . . . , in that the institutional leaders (trustees, president, provost, deans) … are bankers, real estate people, investment dealers, etc. . . . They have . . . [little] understanding of music or the creative process, and do not know how to run a music program[,] as they lack true leadership abilities. At best they are music hobbyists.” Such comments implicate the effects of a lack of valuing on their work and the importance of meaning in leadership.

Relationships. It is clear that relationships matter, as one respondent expressed a positive relationship: “. . . [A] very supportive department chair, open to conversation and change. Chair actively engages in research as well as maintaining a rigorous teaching load. Generally good colleague relations in the department.” This comment demonstrates the importance of an academic leader’s ability to engage with faculty by showing interest in their work. Another professor expressed a lack of in-unit support and relationships, but was still able to develop positive interactions with upper administration, with those relationships shifting their career trajectories:

We have almost no collegiality or support in our department, and I have a very difficult time making any meaningful connections with faculty in other disciplines. I've had the most rewarding interactions[, however,] with administration (including upper administration), and I feel a pull toward that career path, if for no other reason than I actually feel like I'm a part of a team.

Discussion

This study has put a spotlight on the relationship between music executive leadership and faculty. A dichotomous profile emerged in our demographic data where our respondents were composed of a greater representation of males, those who served longer at the current institution, and higher-ranking professors. Specifically, our data show that female and junior-level faculty are more optimistic about relationships, communication, and meaning with respect to their executive leadership than their male and senior counterparts. Interestingly, sustained morale, which received moderately low scores, is strongly associated with a faculty member’s perception of all four work dimensions of PL leadership. We may infer, then, that the faculty could work better and enhance their morale under PL leadership. We see more critical comments about leadership in the context of administrative structure, suggesting that these comments may have come from more experienced senior-level faculty who have a broader and more in-depth understanding of leadership quality and institutional dynamics. Another obvious distinction emerges from the role of leadership in shaping the climate in qualitative data. The expressed comments are more precise and specific about the climate created within the confines of the institutional structure. We also think that while structural hindrance and its effects are easily detectable, affective work factors may be less visible and more nuanced. The goal of content analysis is to capture in-depth thoughts and understand the nuanced nature of the participants’ expressions. In this regard, frequencies of written comments do tell a story: our expected PL dimension order was modified in this data, with the first-order concern remaining with the leadership, followed by structurally related concerns, and then concluded by communication, meaning, and relationship.

Revisiting our initial hypotheses, we did not find evidence to support our first one, involving a “positive relationship between work conditions and [a] leader’s capability to create a positive climate.” Work conditions were found critical to faculty vitality in the previous study (Lee, 1995). However, music faculty in this survey viewed them as less related to their leaders’ capacity to create a positive climate. This is counter to Cameron’s theory (2012) as well. We pause to think that climate may be a complex issue to examine beyond the utility of a quantitative survey instrument. More focused qualitative interviews may be necessary to understand the dynamics between faculty perspectives and climate.

As to our second hypothesis involving “positive relationships between faculty engagement and [a] leader’s ability to create meaning and effective communication,” we find participation in vision setting, curriculum development, and budget planning to be strong indicators of positive leadership in all four areas. This resonates with the research of Grant (2012), Shanafelf (2009), and Vogelgesang et al. (2013).

Regarding our third hypothesis on the relationship between “the evaluation system and the leader’s ability to build relationships,” equitable, systematic, and consistent evaluation, along with fairness in evaluation, were important in a faculty member’s perception of their leader. A takeaway for the music leader is to seek transparency, consistency, and fairness in their evaluation of faculty colleagues.

Concerning our fourth hypothesis, counter to Cameron’s proposition (2012), a “positive relationship between individual perspectives and [a] leader’s ability to develop meaning” was not ascertained. We note, however, that individual perspectives, measured by aspiration to achieve, esteem of one’s own work, a sense of purpose, and sincerity and devotion, were highly rated, affirming the previous study (Lee,1995). Leaders could aim at creating a viable bridge between PL meaning and a faculty’s individual perspectives. What is more, sustained morale is a strong predictor of positive leadership: a capable leader can focus on ways to boost faculty morale.

Our final hypothesis, ”positive relationship between faculty collaboration and the leader’s ability to enhance relationships,” was only partially validated. Specifically, we find that the leader’s ability to enhance the relationship is linked to collaboration with colleagues inside the music field, but not outside. Somewhat to the contrary, in the qualitative response, many faculty stressed the importance of developing collaborative relations with individuals outside the music department. This is promising in the context of the interconnected world where the arts and music can play a more significant role in building the cultural and intellectual life of both academia and society.

Implications

This study highlights several implications for music faculty, academic leaders, and researchers. First, we find that there is little connection between faculty perspectives and a leader’s ability to develop a positive work climate. However, the term climate seems to have evoked strong connotations, as shown in the qualitative portion of our study. Future research can explore the idea of climate in more detail and how it involves more resonant and affective aspects of one’s work life. Academic leaders can glean from this study that a clear and consistent evaluation process, with a well-articulated policy, can help improve faculty perceptions of their leaders via improved climate and communication.

Second, we believe that strong relationships between sustained morale and involvement in a vision setting, with all four positive leadership dimensions, may indicate that faculty seek to work with their academic leaders in order to develop better relationships and climate. Leaders can create avenues for faculty to regularly engage in the vision setting process. Future researchers can identify specific strategies to accomplish collaborative vision setting that could boost faculty morale.

Finally, our results illustrate that faculty see themselves as actors within a complex institution encompassing multiple layers of leadership. Our qualitative analysis indicates that a college’s structure is seen as a barrier to its vitality, and that leaders are perceived as partial architects of that structure. Leaders need to find ways to minimize the negative aspects associated with bureaucracy within higher education, primarily through streamlined processes and transparent policy practices. Further research in this vein could focus on how institutional structures could be recrafted in ways that can enhance faculty engagement.

Musicians both inside and outside of academia are generally regarded as sensitive and expressive. Music professors are also profoundly committed to their art, work, students, and the institution (Lee & McNaughtan, 2019). We can achieve a more apt leadership model in music units if we better understand the nature and long-term value of music and musicians in both the academy and society. One example of further change could be to build a new music executive model by adopting emotional intelligence practices that have permeated the business and medical fields throughout the country (Goleman, 2005; Hasson, 2014; Prins, 2011; Wharam, 2009). Finally, in this study, we regard faculty voices as highly precious within the collegial hierarchical structure, underscoring the maxim, “we are in it together.”

Notes

1. We dedicate this article to Professor Kim Cameron, an eminent higher-education and organizational scholar, who has mentored us, twenty years apart, at the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education at the University of Michigan.

2. Sociometry is a quantitative measurement of social distances and affinities among people, including patterns in friendships, social networks, work conditions, satisfaction, and support systems. Psychometry is a quantitative measurement of intelligence, personality, attitude, morale, and job satisfaction among many human psychological dynamics (Miller 1991).

Lee’s music faculty questionnaire (1995), derived from the synthesis of comprehensive faculty studies in higher education, was validated by two focus groups—each one comprising 24 music faculty members—from two major universities (University of Michigan and Eastern Michigan University). Cronbach’s alpha was used to test the reliability (departmental conditions alpha ranged from 75 to 97; faculty vitality range of 46 to 84) from a national random sample of 745 ranked music professors. The College Music Society’s Review Committee, charged by the Executive Director Robby Gunstream, evaluated the 1995 instrument for appropriateness and currency for the proposed 2015 Music Faculty Study (Taylor, 2014). The College Music Society compiles a complete roster of music faculty annually in all NASM certified music programs regardless of their institutional or individual affiliation with CMS. Historically, CMS has been supportive of professional research on faculty issues.

The consensus for an acceptable number for quantitative study in the social sciences is >500. For further discussion on sample size, see https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm or https://statisticsbyjim.com/hypothesis-testing/sample-size-power-analysis/

3. Executive leadership and Faculty perspective variables are derived from factors in Lee (1995). Executive leadership was adopted from Factor 1 of Departmental Conditions (with nine-item factor loadings of .81, .79, .85, .85, .82, .81, .70, .86, .84 and Cronbach’s Alpha, .97; see the table below). We selected 19 faculty perspective variables from Departmental Conditions: (1) Factor 5-Working Conditions (with loadings .66, .77, Cronbach’s alpha .75); Factor 7-Evaluation System (factor loadings of .76, .57, and Cronbach’s alpha .85); and (3) Faculty Vitality, Factor 1- individual perspectives (with factor loadings .58, .72, .76, .56, .45, .50, .44, .38 and Cronbach’s alpha .82).

4. Multiple classification, dummy variables, or nonparametric models are other analytical options. See https://www.xlstat.com/en/solutions/features/ordinary-least-squares-regression-ols.

5. Grounded Theory was a new investigative qualitative method developed by American sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967) to describe a qualitative approach with no preconceived hypothesis that used continually comparative data analysis. The theory obtained by this method originates from the data. Creswell (2009) further articulated “a qualitative strategy of inquiry in which the researcher derives a general, abstract theory of process, action, or interaction grounded in the views of participants in a study” (p.12 & 229). Creswell continues: “[T]he primary characteristics of grounded theory research design [are]: 1) the constant comparison of data with emerging categories and, 2) theoretical sampling of different groups to maximize the similarities and differences of information” (p.13). Also see http://avantgarde-jing.blogspot.com/2010/03/grounded-theory.html#:~:text=According%20to%20Creswell%20(2009)%2C,a%20study.%E2%80%9D%20 and Johnson (2015).

References

Ary, D., Jacobs, L.C., & Razavieh, A. (1996). Introduction to research in education (5th ed.). Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Aziz, S., Mullins, M. E., Balzer, W. K., Grauer, E., Burnfield, J. L., Lodato, M. A., & Cohen‐Powless, M. A. (2005). Understanding the training needs of department chairs. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 571–593.

Baldwin, R. G. (1983). Variety and productivity in faculty careers. New Directions for Higher Education, 41, 63–79.

Baldwin, R. G. (1990). Faculty vitality beyond the research university: Extending contextual concept. Journal of Higher Education, 61(2), 160–180.

Bare, Alan C. (1980). The study of academic department performance. Research in Higher Education, 12(1), 3–23.

Blackburn, R.T., Bieber, J. P., Lawrence, J. H., & Trautvetter, L. C. (1991). Faculty at work: Focus on research, scholarship, and service. Research in Higher Education, 32(4), 385–413.

Buller, J. L. (2013). Positive academic leadership: How to stop putting out fires and start making a difference. Jossey-Bass.

Cameron, K. S. (2012). Positive leadership: Strategies for extraordinary performance (2nd ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Clark, S. M., Boyer, C. M. & Corcoran, M. (1985). Faculty and institutional vitality in higher education. In Clark, S. M. & Lewis, D. R. (Eds.). Faculty vitality and institutional productivity: Critical perspective for higher education (pp. 3–24). Columbia University Press.

Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Skoner, D., Rabin, B. S., & Gwaltney, J. M. (1997). Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. Journal of the American Medical Association, (277), 1940–1944.

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Cowden, R. L. & Klotman, R. H. (1991). Administration and supervision of music (2nd ed.). Schirmer Books.

Creswell, J. W. and Brown, M. L. (1992). How chairpersons enhance faculty research: A Grounded Theory study. The Review of Higher Education, 16(1), 21–62.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches. Sage.

Dutton, J. E. & Heaphy, E. D. (2003). The power of high-quality connections. In K.S.

Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 263–278). Berrett-Koehler.

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence. Bantam Books.

Grant, Kerry S. (1992). Developing Faculty Resources. Proceedings: The 67th Annual Meeting of the National Association of Schools of Music, Number 80. Orlando, Florida, November 23–26, 45–63.

Grant, A. M. (2012). Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 458–476.

Hasson, G. (2014). Emotional intelligence: Managing emotions to make a positive impact on your life and career. Capstone.

Heaphy, E. D. (2007). Bodily insights: Three lenses on positive organizational relationships. In J. E. Dutton & B. R. Ragins (Eds.) Exploring positive relationships at work (pp. 47–72). Erlbaum.

Heaphy, E. D., & Dutton, J. E. (2008). Positive social interactions and the human body at work: Linking organizations and physiology. Academy of Management Review, 33, 137–163.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Uchino, B. N., Smith, T. W., Olsen-Cerny, C., & Nealey-Moore, J. B. (2003). Social relationships and ambulatory blood pressure: Structural and qualitative predictors of cardiovascular function during everyday social interactions. Health Psychology, 22, 388–397.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Hutchison, A. J., Johnston, L. H., & Breckon, J. D. (2010). Using QSR‐NVivo to facilitate the development of a Grounded Theory project: An account of a worked example. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(4), 283–302.

Jones, J. B. (1986). Music performance faculty in higher education: Their work and satisfaction [Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University].

Johnson, Jeff S. (2015). Qualitative sales research: An exposition of Grounded Theory. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 35(3), 262–273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2014.954581

Kahn, W. H. (2007). Meaningful connections: Positive relationships and attachments at work. In J. E. Dutton & B. R. Ragins (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work (pp. 189–206). Erlbaum.

Knight, P. T. & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Departmental leadership in higher education. Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

LeBlanc, A. & McCrary, J. (1990). Motivation and perceived rewards for research by music faculty. Journal of Research in Music Education, 37(1), 61–68.

Lee, S. (1995). Departmental conditions and music faculty vitality (Publication No. 9527679) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Michigan]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305180448_Departmental_Conditions_and_Music_Faculty_Vitality

_University_of_Michigan_1995_Ann_Arbor_Michigan_ProQuest_Pub_9527679_ProQuest_Dissertations_Theses_PQDT_Full_Text.

Lee, S. & McNaughtan, J. (2019). Music faculty role and organizational commitment. College Music Symposium, 59(2), 1–30.

Miller, D. C. (1991). Handbook of research design and social measurement (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Morse, J. M. and Richards, L. (2002). Reading first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods. Sage Publications.

Murnighan, J. K & Conlon, D. E. (1991). The dynamics of intense work groups: A study of British string quartets. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 165–186.

Nelsen, W. C. (1981). Renewal of the teacher-scholar: Faculty development within liberal arts colleges. Association of American Colleges.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Sage.

Prins, A. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Tipping point in workplace excellence. Knowres Publishing.

Rigoni, B & Nelson, B. (2016). Do employees really know what’s expected of them? Business Journal. http://www.gallup.com/businessjournal/195803/employees-really-know-expected.aspx?g_source=turnover%20manager&g_medium=search&g_campaign=tiles

Risenhoover, M. (1972). Artist-teachers in universities: Studies in role integration [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Michigan].

Roberts, L. M. (2007). From proving the becoming: How positive relationships create a context for self-discovery and self-actualization. In J. E. Dutton & B. R. Ragins (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work (pp. 29–46). Erlbaum.

Ryff, C. D., Singer, B., Wing, E., & Love, G.D. (2001). Elected affinities and uninvented agonies: Mapping emotion with significant others onto health. In C. D. Ryff & B. Singer (Eds.), Emotion, social relationships, and health (pp.133–175). Oxford University Press.

Shanafelt, T. D. (2009). Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. Jama, 302(12), 1338–1340.

Taylor, S. E. (2002). The tending instinct: How nurturing is essential for who we are and how we live. Time Books.

Taylor, J. (2014). Letter from CMS Committee Chair to communicate CMS endorsement of the survey instrument, Music Faculty Questionnaire: Faculty Vitality and Organizational Conditions. Email correspondence dated January 17, 2014.

The College Music Society (2018). Professional notices via email. List by specialization.

Tummers, L., Steijn, B., Nevicka, B., & Heerema, M. (2016). The effects of leadership and job autonomy on vitality: Survey and experimental evidence. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 1–23.

Vogelgesang, G. R., Leroy, H., & Avolio, B. J. (2013). The mediating effects of leader integrity with transparency in communication and work engagement/performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(3), 405–413.

Weber, L. (2015). What do workers want from the boss?. The Wall Street Journal. http://blogs.wsj.com/atwork/2015/04/02/what-do-workers-want-from-the-boss/?mod=e2tw

Wharam, J. (2009). Emotional intelligence: Journey to the center of yourself. O Books.

Wrzesniewski, A. (2003). Finding positive meaning in work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 296–308). Berrett-Koehler.

Zey-Ferrell, M. & Baker, P. J. (1984). Faculty work in a regional public university: An empirical assessment of goal consensus and congruency of actions and intentions. Research in Higher Education, 20(4), 399–426.

Appendix