Abstract

Exemplifying his approach to musical nationalism, the Misa folclórica paraguaya (“Paraguayan Folkloric Mass”) of Florentín Giménez (1925–2021) combines elements of the Roman Catholic Mass with folkloric music idioms. Composed in 1990, this musical work represents Giménez’s intention to develop a concert piece based on Paraguayan music in a liturgical context. Throughout his long career as a composer, conductor, educator, and advocate for the promotion of Paraguayan cultural identity, Giménez has conveyed his ideas about Paraguayan music and nationalism via his musical works. Based on an analysis of the Misa folclórica paraguaya—including his manuscript, revisions, published score, recordings, and a series of personal interviews, this article explores Giménez’s understanding of Paraguayan musical nationalism, presents the historical and musical context for his setting of the liturgical piece, and discusses the significance of his musical ideals in connection to his works, and more specifically to the Misa folclórica paraguaya as a liturgical celebration and representation of Giménez’s cultural identity and musical nationalism.

Vincent Benitez

In his Misa folclórica paraguaya (“Paraguayan Folkloric Mass”), composed in 1990 and premiered two years later on September 8, 1992, Florentín Giménez (1925–2021) sets parts of the Roman Catholic Mass using folk-style music idioms to underscore elements of Paraguayan musical nationalism.1This article constitutes one of the first musicological publications in English on the music of Paraguayan composer Florentín Giménez. The author presented a conference paper related to this topic at the 2019 Fall Meeting of the Southwest Chapter of the American Musicological Society. I am grateful to Mr. Giménez, who kindly shared with me recordings of his folkloric mass, as well as the published version of the score. I would also like to acknowledge Adam Cogliano for his timely assistance with the musical notation and transcription of selected sections of the Mass. Unless indicated otherwise, all English translations are mine. Finally, I have included a Glossary of key terms and their definitions. These elements include specific beliefs about Paraguayan cultural identity and the use of folk-style music genres within the context of a type of musical advocacy.2Throughout this article, I use “folk-style music” instead of “folk music,” since the former term better describes the compositional style of Giménez, whereas the latter one implies music deriving from oral traditions and reflecting anonymous authorship. Based on the analysis of Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya—including the composer’s manuscript, revisions, published score, recordings, and a series of personal interviews, this article explores Giménez’s understanding of Paraguayan musical nationalism, presents the historical and musical contexts for his setting of the liturgical piece, and discusses the significance of the composer’s musical ideals in connection to his works, and more specifically to the Misa folclórica paraguaya as a liturgical celebration and representation of his cultural identity and musical nationalism.3Although the topic of Paraguayan folkloric Masses stands out as one of the numerous musicological lacunae in Paraguayan music research, the intention of the present paper is to fill that void partially by discussing Florentín Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya. Because this study’s main focus is the work by Giménez, a detailed discussion of other Paraguayan folkloric masses is outside the scope of this paper. Fortunately, besides brief references to a few of these works in publications by Pedrozo (2003) and Szarán (1977), Alvaro Morel’s research on Herminio Giménez’s 1974 Misa folclórica (2009) provides a concrete background on Herminio Giménez’s work as well as context and information regarding others.

Florentín Giménez: Biographical Sketch

Florentín Giménez Martínez was born in 1925 in Ybicuí, Paraguay (Giménez 2008).4The biographical sketch is based on the composer’s memoir. See Florentín Giménez (2008). At the age of fifteen, he moved to Asunción and became a music apprentice with the Asunción Police Academy Music Band, an institution that offered musical instruction to underprivileged children and youth. Concurrently, he studied piano and harmony with other instructors and earned a piano teaching certificate in 1948. After collaborating with various local bands, in 1950 he founded his own orquesta típica (tango orchestra), a musical ensemble devoted to the performance of the popular music of the times, mainly Argentinian tangos, Brazilian sambas, US American fox-trots, Cuban rumbas, Mexican boleros, and Paraguayan polcas and guaranias.5According to Giménez, in addition to a vocalist, an orquesta típica may include two or more bandoneones, one or more violins, a double bass, and a piano, usually played by the leader of the ensemble. While the polca paraguaya or simply polca—sometimes also referred to as kyre’ỹ and in certain contexts as galopa—is a lively song and dance form in compound duple meter with sesquialtera/hemiola rhythmic characteristics, the guarania is its slow and relaxed song-form counterpart. In general, both the Paraguayan polca and the guarania exhibit repetitive musical phrases and a harmonic vocabulary derived from tonic-dominant-subdominant relationships. Typically, the guitar and diatonic harp—as well as the accordion, violin, and double bass or electric bass nowadays—accompany Paraguayan polcas and guaranias. For more information on these musical genres, see Alfredo Colman (2014).

In 1956, Florentín moved to Buenos Aires, where he collaborated with various musical ensembles and embarked on a course of study that included music theory at the Conservatorio Carlos López Buchardo, contemporary harmony at the Instituto Torcuato di Tella, and private composition and orchestration with the Italian-Argentinian maestro Cayetano [Gaetano] Marcolli. In collaboration with Ben Molar, owner of Ediciones Internacionales Fermata—a major music-publishing house and recording label in Buenos Aires, Giménez produced a series of “hit” songs that were widely disseminated and recorded by well-known local and international artists in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s.6Composed in 1956, Giménez and Molar’s Muy cerca de ti (“Very Close to You”) became an “overnight success” and was recorded by artists such as Argentinian jazz composer Angel “Pocho” Gatti, singers Roberto Yanés and Estela Raval, Brazilian pianist Daniel Salinas and singer Martha Mendonça, the Mexican Trío Los Panchos, numerous Paraguayan soloists and conjuntos (vocal ensemble accompanied by two guitars or two guitars and a harp), and US American singers Freddie Davis and Andy Russell, among others.

Upon his return to Paraguay in 1969 and for the next several decades, Giménez remained one of the most active musical figures in the country: first as assistant conductor of the Asunción Symphony, also known as OSCA (1974–77), then as main conductor of that ensemble and the Municipal Chamber Orchestra or OCM (1977–89). From 1990–96, the Paraguayan Senate designated him “Composer in residence of the city of Asunción.” During the 1990s, Giménez founded two major musical institutions—the Music Conservatory of the Catholic University (1992) and the National Conservatory (1996)—and developed a proposal to create the bi-annual National Music Award (1994), which became official shortly thereafter. In 2004, he founded the National Symphony Orchestra and conducted it until his retirement four years later.

Giménez is a prolific composer, with musical works that include:

- More than eight hundred folkloric songs

- A sonata and a collection of preludes and fugues for piano

- The Paraguayan folkloric mass

- An opera entitled Juana de Lara

- Thirteen Paraguayan zarzuelas

- Three instrumental suites

- Two pieces for symphonic band

- A concertante for piano and orchestra

- Three concertos for violin, viola or cello, and two guitars, respectively

- Three symphonic poems and nine symphonies.

Giménez has also published books dealing with Paraguayan music, culture, and folklore as well as fiction.7In addition to monographs addressing Paraguayan music and culture—La música paraguaya (1997), Rasgos tradicionales del folklore paraguayo (1999), and El Decálogo sonoro (2017), Giménez has published a memoir entitled Historia sin tiempo (2008, revised in 2013) and a series of four novels: (1) Indalecio (2007, 2009), (2) Rasgos y pasiones (2007), (3) Isabela (2010, 2012), and (4) Samunko (2010, 2017). For full details, see the Reference list at the end of this article. In recognition of his musical achievements, Giménez has received numerous awards and accolades, including three honorary doctorates from Paraguayan universities, the Orden de Comendador (National Order of Merit as Knight Commander) in 1997—the highest recognition awarded by the Paraguayan government to any civilian, and on two occasions the National Music Award.8The honorary doctorates have been conferred by the Universidad Nacional de Asunción (2006), the Universidad Metropolitana de Asunción (2007), and the Universidad Nacional de Pilar (2014). Giménez received the Premio Nacional Música in 2001 and in 2015, the first time for his Sinfonía No. 1 en Re Menor “Metamorfosis,” and the second time for his opera, Juana de Lara. Though most of his concert works remain unpublished, his collection of folk songs have been published in six cancioneros (songbooks), and several of his pieces have been released by various Argentinian, Brazilian, and Paraguayan recording labels.

Giménez’s Musical Nationalism

Giménez’s musical nationalism is a “subjective one” that is closely related to the types of folk sources he uses and the way in which he composes. His works constitute a lens through which one could observe a kaleidoscope of ideas illustrating, describing, and even prescribing that which makes Paraguayan music distinctly Paraguayan. For Giménez, his compositions constitute true examples of these ideas. During one of my first interviews with the composer on June 30, 2011, he pointed out that his collected works were distinctive signifiers of the spirit and identity of Paraguay, echoing to some extent the concepts of nation and cultural representation as presented in late twentieth-century sociological studies (Hall and du Gay 1996; Hall et al. 1996). During the interview, Giménez stated that:

. . . I always wanted to enter into the music field, that of erudite music, because it is the only one that carries and transmits with its invariable character everywhere. . . . I am a musician of nationalist conception [emphasis mine], and my symphonic works stand as those that motivated [composers such as] the Brazilian Villa-Lobos, Alberto Ginastera, [Victor] Tevah, all the Latin Americans. I always thought that my musical works . . . are works that identify this country in the context of the world.

Florentín Giménez’s musical nationalism can be essentially explained by two main ideas associated with a practical display of the culturally and socially-embedded paraguayidad (Paraguayan-ness): pride and duty. Thus, his nationalism is demonstrated in the cultural pride and social duty that he experiences in creating musical works that concentrate on specific Paraguayan topics. Although Giménez’s use of the phrase “musician of nationalist conception” could also be explained as a description of a Paraguayan composer empowered and inspired by sounds coming from traditional music as well as specific events transmitted by the historical memory, that explanation should be considered within the context of highly complex social constructions, political factors, personal circumstances, and specific events that have influenced his musical formation and consequent production.

As scholars studying folklore, nationalism, national-identity formation, and cultural representation have argued, to some extent, political and social agendas influenced by European ideas have informed the concept of cultural identity in Latin America. Considering the concept of nationalism promoted in nineteenth-century Europe as a complex of ideas reflecting a sense of belonging and unity among people (e.g., the observations of counter-Enlightenment philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder [1744–1803] on the nation), and the understanding of folklore as artistic expression communicating the “national” (Dahlhaus 1989, 90–102), multiple case studies have demonstrated that musical nationalism in Latin America has not been a monolithic phenomenon.

For instance, by briefly thinking about how imported nation-building ideas have taken root in a Latin-American context, one will notice the breadth of complexities between regional nationalisms and cultural identities. In connection with the various intellectual and political agendas and movements that developed in the twentieth century, “national” ideas linked with specific “national” elements were systematically inculcated and promoted distinctively in each country: thus, the gaucho tradition in Argentina, musical folklore in Brazil, the Aztec and the indigenous in Mexico, the Afro-Cuban element in Cuba, and others (Béhague 1979, Wong 2004, Pérez Montfort 2008). Further examples of this phenomenon have been observed through the performance of folk-style music as a medium to express profound sentiments of national pride connected with identity and patriotism, as in the case of Chile, or as a lens to display a variety of folkloric practices at the Festival Nacional de Folklore Argentino (Mularski 2014, 1–67; Florine 2016, 51–102). Other studies in the twenty-first century have analyzed musical nationalism within the complex of cultural nationalism, as in the employment of music to achieve specific nationalist goals, such as popular music in Brazil or twentieth-century concert music in the context of Pan Americanism (Turino 2003, 169–209; Avelar and Dunn 2011, Hess 2013).

To be sure, this type of nationalism has become a cultural script developed to support social interaction and solidarity as well as a medium promoting certain cultural imaginaries to justify historical and political processes. For Giménez, being part of this conversation on nationalism and cultural identity has become a recurrent feature of his compositions, writings, publications, and conference presentations. He views himself as not only associated with Paraguayan and Latin-American folk-style music and culture but also in a continuous conversation with composers of concert music. In his memoir, Giménez lists a selected group of nationalist composers, including Paraguayan (José Asunción Flores, Francisco Alvarenga), Latin-American (Héitor Villa-Lobos, Carlos Chávez), US American (George Gershwin, Aaron Copland), and European musicians (Joaquín Turina, Béla Bartók, Bedrich Smétana, Maurice Ravel, Manuel de Falla, Aram Khatchaturian, Modest Mussorsgsky, and Alexander Borodin) with whom he identifies in a “fervent embrace” (Giménez 2008). By identifying himself with these nationalist composers, Giménez believes, in the final analysis, that he assumes a distinctive approach and perspective that allows him to address the intricacies of Paraguayan musical culture and thus compose and illustrate its most salient aspects.

Giménez regards his musical nationalism as reflecting the proper understanding of paraguayidad or Paraguayan cultural identity, which for him constitutes the essence of being a good and authentic Paraguayan—in other words, an individual who is proud of his heritage and culture.9For a detailed discussion on the topic of paraguayidad, see chapters 1 (“On Identity, Paraguayidad, and Tekó”) and 2 (“Paraguayidad and Paraguayan Identity”) in Colman (2015). In the Paraguayan social imagination, through education and the government’s inculcation of certain beliefs and values, the commonly explained understanding of paraguayidad has been expressed and transmitted through ideas such as love for the land and its natural resources and a deep appreciation for Paraguayan historical memory and Guarani culture. By embracing and promoting national themes through his music, Giménez believes that his duty as a Paraguayan citizen and composer has been fulfilled.

While for Giménez a practical display of paraguayidad is connected to his pride and duty as a citizen, his ideas concerning cultural identity run parallel with another socially embedded concept: the tekó, that is, Guaraní for the “Paraguayan way of being.” As observed by the linguist-anthropologist Bartomeu Melià (1932–2019) and sociologist Gerardo Fogel (1936–2019), in the social imagination of the Paraguayan people, the action and performance of their way of being moves an individual to express his or her own social and cultural identity through specific practices, such as the performance of music, including song and dance (Colman 2015, 10–14, 18–21). In the context of the Paraguayan tekó as a signifier of practices associated with Paraguayan folklore, tradition, and culture, I argue that in his compositions, Giménez's approach exemplifies the embodiment of this complex and intrinsic aspect of the Paraguayan experience.

Giménez’s Cultural and Musical Ideals

According to Giménez, the Misa folclórica paraguaya falls within the category of obras populares (popular works), which he has published in six songbooks. Along with the Mass, Giménez’s more than 800 folkloric songs testify to his productivity in Paraguayan music. Indeed, Giménez regards the use of folk idioms and the various Paraguayan musical genres featured in portions of the Mass as highlighting a personal testament of cultural identity through the lens of the most archetypal Paraguayan musical forms. He not only aims to provide examples of those musical forms and genres in a practical way but also to indicate how they should be approached, treated, and transmitted.

A tireless promoter of music and culture, Giménez considers his musical works as models of how to compose, notate, and preserve Paraguayan music. Countless performances and recordings of his pieces have translated into sound his intention to defend and promote the integrity of Paraguayan music as a type of cultural advocate. For example, as explained by the composer, one way in which Giménez defends the integrity of Paraguayan music is to translate on paper and into sound how both melodic phrases and rhythmic values must be notated and performed.10Lamenting the lack of musical understanding among the majority of current Paraguayan musical performers, Giménez has also addressed this particular issue on radio, television, and in newspaper interviews, as well as through interactions on social media.

In order to accomplish his musical education goals during the 1990s, Giménez established two major musical institutions in Paraguay, the Music Conservatory of the Catholic University and the National Conservatory. He also engaged in music research and writing, which resulted in the publication of two significant music monographs, La música paraguaya (“Paraguayan Music”) in 1997 and Rasgos tradicionales del folklore paraguayo (“Traditional Characteristics of Paraguayan Folklore”) in 1999.

Besides recording his own compositions, Giménez has been a passionate advocate for the orchestration and dissemination of specific folkloric works by other Paraguayan composers. His experience as a pianist and ensemble director of various orquestas típicas in the 1950s and 60s, as well as his conducting tenures with the Asunción Symphony (1970s to 80s) and the National Symphony (2004–8) provided Giménez with the opportunity to select, arrange, orchestrate, and perform his own canon of representative Paraguayan music pieces, works that are still promoted and performed by these and other ensembles.11For instance, Giménez produced studio recordings of his arrangements of traditional music (Tierra de guaranias and Inédita 12 [1979]), and with the chamber ensemble Camerata Asuncena, in 1981 and 1982 he recorded a series of television broadcasts highlighting Paraguayan folk-style music.

In addition to scheduled concerts of the Asunción Symphony and the National Symphony that were devoted exclusively to Paraguayan music, Giménez developed the practice of including folk-style music in almost every regular concert of these two major orchestras. Giménez was concerned about the proper notation of Paraguayan folk-style music that dates back to the 1950s when he witnessed music copyists and arrangers working while commissioned to notate new pieces for copyright and registration purposes in Buenos Aires. Several of these copyists, as Giménez remembers, were not properly trained to write guaranias and Paraguayan polcas in compound duple meter, rendering them instead in triple meter. Since then, he has attempted to train fellow composers, performers, arrangers, and conservatory students to more accurately notate and perform Paraguayan folk-style music. This zeal for the proper application of Paraguayan music reached a new level through the creation of a musical form: the pupyasy.

In 2007 and after several decades of using terms such as polca paraguaya, kyre’ỹ, along with the galopa to designate the lively character of this Paraguayan air and form, Giménez proposed a new designation for them: a combination of two words in Guaraní, pupy (“nucleus of sounds”) and asy (“soulful emotion” or “sensitivity”). He did this not only to show a closer connection with Paraguayan culture but also to replace common terms adapted from foreign words—mainly “polka” and “gallop”—in order for him to designate genres within the Paraguayan musical vocabulary.12Curiously, starting with the third Cancionero (2011), the lively songs earlier labeled [Paraguayan] polcas have been referred to and published under this new designation. Showing and maintaining a strong connection with Guarani culture has been an imperative for Giménez in his goal to promote a Paraguayan cultural identity. He believes that since Guarani words possess an inherent musical quality or sound (having a specific inflection, pattern of accentuation, or cadence), the act of speaking Guarani is one of the first steps in learning how to sing and play traditional music in a way that portrays an aspect of “Paraguayan-ness.” In La música paraguaya the composer explains this particular point: “The Guaraní [language] is flowing in its movement and [at the same time is] musically syncopated [in its sound]; it influences greatly the native musical airs when musicalized poems are expressed with our spiritual [Paraguayan] essence” (Giménez 1997, 335–36).

In addition to texts in Guaraní set to the sounds of Paraguayan folk-style music, Giménez believed that the use of Guaraní terminology to designate musical styles authenticates them as carriers of that identity. In a practical way, his application of the term pupyasy functions as a construct and musical signifier of paraguayidad and as a transmitter of cultural identity.13Whereas other Paraguayan composers and performers have employed the term pupyasy, polca paraguaya or polca still remains the preferred designation for the general public. By considering Giménez’s ideas and achievements in the context of his music education advocacy—discussing issues related to Paraguayan music, developing orchestral arrangements of folk-style music in a concert setting, emphasizing the Guarani language as a major connector with Paraguayan folk-style music, and creating a new term to redesignate long-standing folk-style music genres, to name a few—I argue that the Misa folclórica paraguaya illustrates the composer’s ideas and summarizes his intention to promote and solidify such points.

Misa folclórica paraguaya

Immediately after being dismissed as main conductor of the OSCA (1977–89), Giménez received the official designation of “Composer in residence of the city of Asunción.”14In his 2008 memoir (337–53), Giménez provides a vivid account of the circumstances and events leading to his dismissal from the Asunción Symphony. During my interview with the composer on June 24, 2020, he indicated that one of the reasons behind his dismissal was the accusation that he was a supporter of the regime of President Alfredo Stroessner, which was ended by a military coup d’etat in February 1989. In the words of Giménez, “[w]hen Stroessner’s government fell, I was accused of being a stronista.” In 1990, during the first year of this new appointment, Giménez completed three large-scale works: (1) the Misa folclórica paraguaya, (2) the Sinfonía-Ballet No. 4 en Sol Mayor “Sortilegio” (“Ballet-Symphony No. 4 in G Major ‘The Spell’”), and (3) the Fantasía étnica (“Ethnic Fantasy”) for symphonic band. That year, the OSCA premiered the Ballet-Symphony No. 4 and the Asunción Police Symphonic Band the Ethnic Fantasy. In 1992 a chamber ensemble comprised of soloists, a choir, a folkloric conjunto, and a small orchestra premiered the Misa folclórica paraguaya.

First conceived under the title of Misa festiva (“Festive Mass”), the Misa folclórica paraguaya was planned (according to Giménez) as a musical work straddling the erudite and popular, and although not following it strictly, in the context of the Ordinary of the Mass. In two separate publications (Giménez 2008, 2011), Giménez referred to the work. Discussing his motivation, the composed recalls the following in his memoir:

In January of 1990, during my morning walks through the small streets of my beloved [town of] Ytú, I started sketching the [musical] themes for a “Paraguayan folkloric mass.” For several years I had desired to add to my musical works, …a piece that would free me from that heresy concocted as a weapon of everlasting condemnation by my domestic enemies,…Those who politically ruled [Paraguayan] culture, before leaving the country and also fourteen years later after my return. (Giménez 2008, 360)

In the preface to Cancionero V, where Giménez’s “Paraguayan Folkloric Mass” is included, the composer states:

. . . as I had promised after my years of musical studies [in Argentina] and my return to Paraguay, I decided to add my name to the musical creators of this liturgical genre with the native airs and sounds of our country, to thus produce an original score with a true content of our folkloric sources; a work composed for large orchestra, folkloric conjunto, vocal quartet, and a large mixed choir, dedicated to the most beloved Virgin of Ka’akupe. (Giménez 2011, notes to Misa folclórica, unnumbered pages after Obp. 697)

By comparing Giménez’s statements, we can discern several ideas lying behind the composition of the Mass. Besides desiring to complete a liturgical music project highlighting elements of Paraguayan folk-style music, the Mass became part of a series of works composed during his new assignment as composer-in-residence in Asunción. Moreover, during an interview on June 24, 2020, Giménez confirmed that his Folkloric Mass had also been conceived as a personal prayer and manifesto regarding the personal harassment he received and that precipitated his dismissal as main conductor of the Asunción Symphony.15During the same interview, Giménez stated that “I was deeply hurt after what they have done to me, then that motivated me to compose the Mass as a personal prayer.”

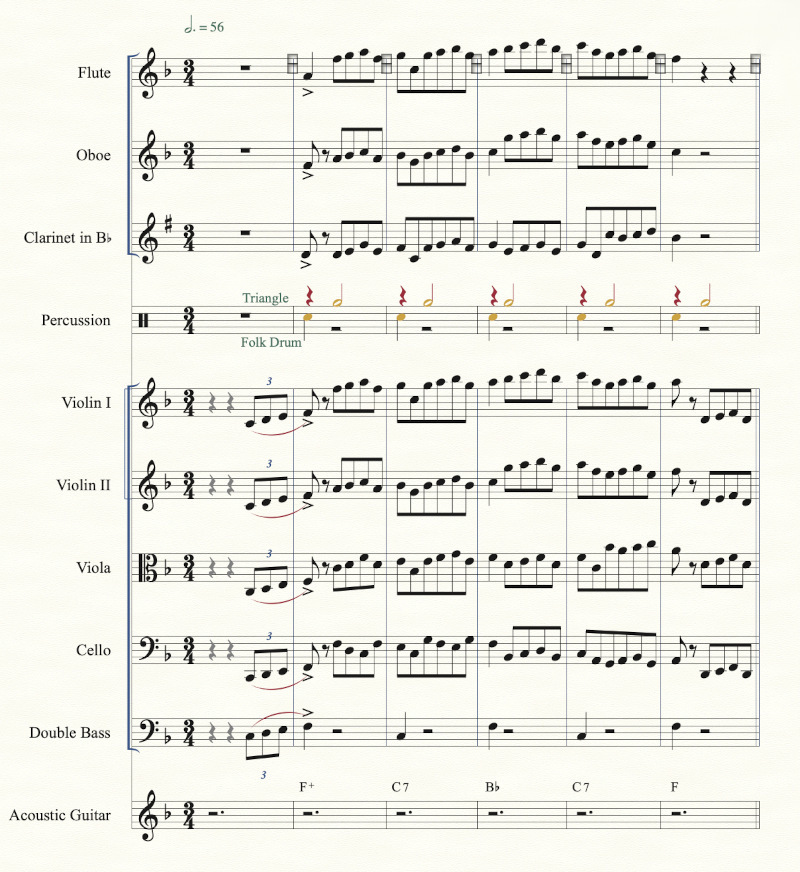

Giménez’s Mass is orchestrated for flute, oboe, clarinet in B-flat, percussion (bombo, triangle), guitar, soloists, conjunto folclórico (folkloric ensemble), choir, and strings.16Played with a soft-headed mallet and a stick, the bombo is a double-headed drum covered with the cured skin of animals (goat, cow, or sheep). In this particular case, conjunto folclórico refers to a vocal ensemble with four singers accompanied by two guitars. Following the suggestion of Monseñor Demetrio Aquino (1926–2003), a personal friend and bishop of the Diocese of Caacupé at that time, Giménez renamed his Misa festiva as Misa folclórica paraguaya. Years later, he added the subtitle A la Virgen de Ka’akupé (“To the Virgin [Mary] of Ka’acupé”), as well as an opening hymn in the manner of an Introit.17Celebrated on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary (December 8), “Our Lady of the Miracles of Caacupé” has been consecrated as the Patron and Lady Protector of Paraguay. Though Caacupé (the town) was founded on April 4, 1770, a chapel was dedicated to the Virgen de Caacupé in 1769. For more details, see “Caacupé: el santuario, la leyenda y la imagen de la patrona de Paraguay,” Catholic.net, accessed June 23, 2020, https://es.catholic.net/op/articulos/60421/cat/99/caacupe-el-santuario-la-leyenda-y-la-imagen-de-la-patrona-de-paraguay.html#modal. Under the guidance of Monseñor Aquino and by suggestion of then theology student Catalino Claudio Giménez (b. 1940), who later became bishop of Caacupé, the composer inserted various readings from the Book of Psalms throughout sections of the Mass.

Looking at the title of the work, Misa folclórica paraguaya highlights distinctive elements found in Paraguayan música folclórica or música popular, intercheangable phrases that Paraguayan composers and performers frequently used to designate a type of Paraguayan urban music that not only was inspired by folk-music idioms but also depicted strong sentiments of cultural identity.18The historical background and social development of the concept of música folclórica and the closely related folklore de proyección have also been studied by specialists analyzing the folk-style music of other Latin American countries. See Florine (2016), Rodríguez (1986, 1989, 2001, 2013, 2018), and others. Introduced throughout the work, the melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic folk-music idioms employed by Giménez derive from genres such as the polca paraguaya or kyre’ỹ and the guarania, among others.

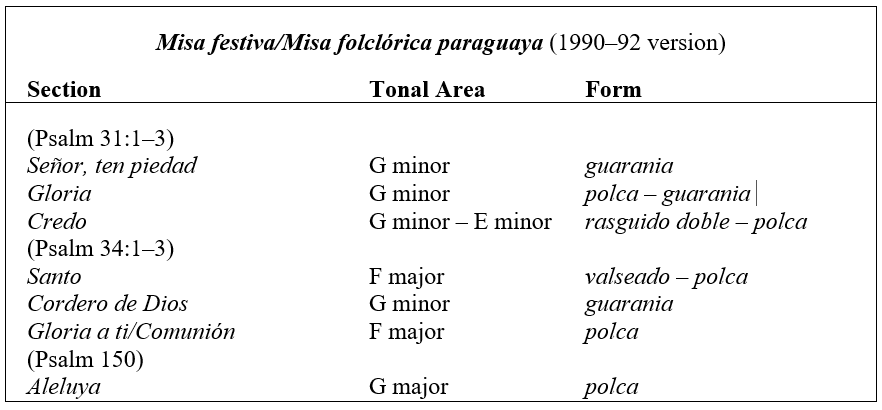

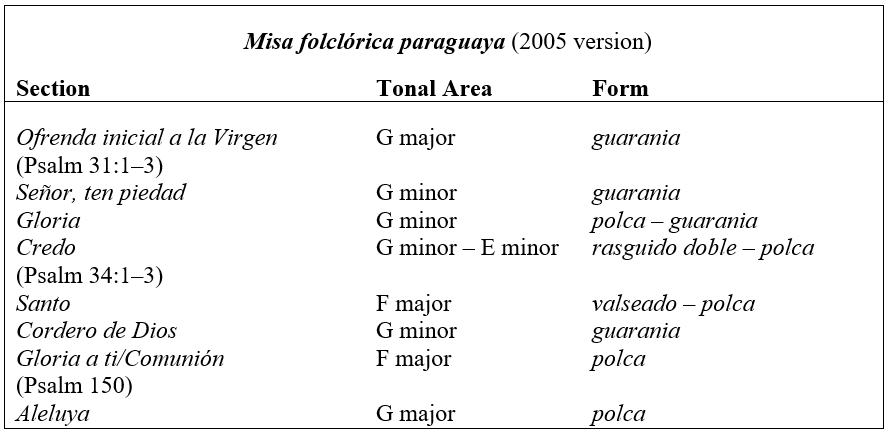

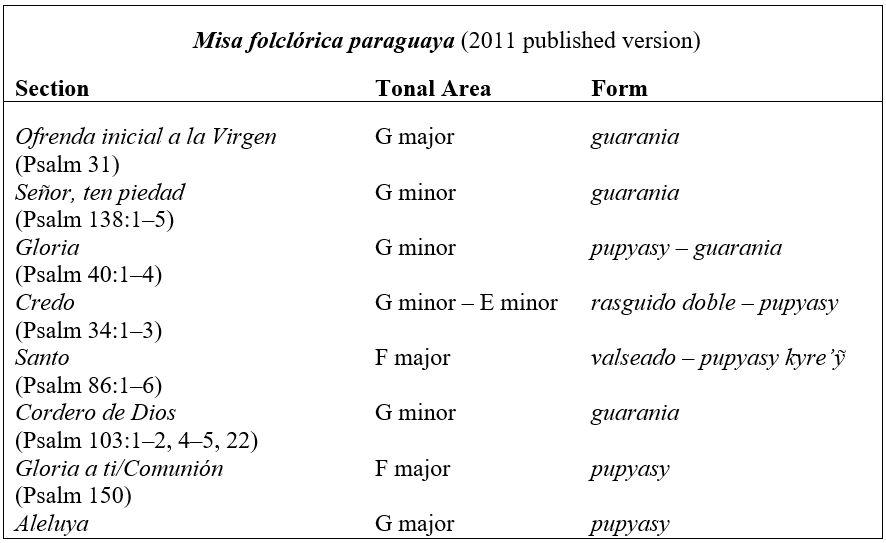

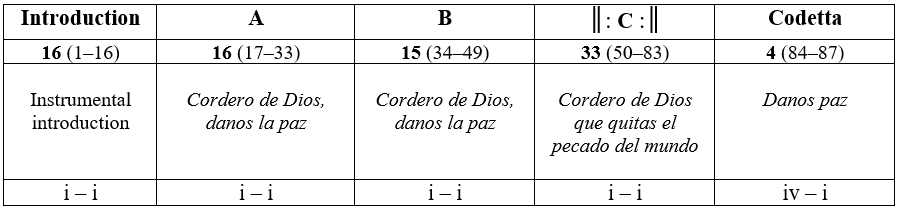

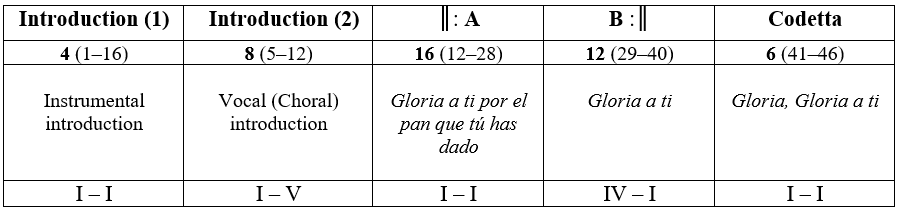

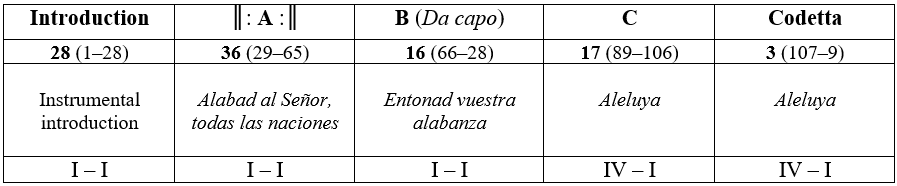

Revised at different times by Giménez (1990, 1992, 2005, 2011), the last version of the work (2011) begins with the hymn Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen (“Initial Offering to the Virgin [Mary of Caacupé]”).19The 1992 score did not include the Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen as part of the Misa folclórica paraguaya. Instead, it appeared for the first time in the 2005 recording version. A series of declamatory readings from the Psalms precede the various movements of the Mass; thus (1) Psalm 31:1–3 before the Señor, ten piedad (“Lord, have mercy”/Kyrie); (2) Psalm 138:1–5 before the Gloria; (3) Psalm 40:1–4 before the Credo; (4) Psalm 34:1–3 before the Santo (Sanctus); (5) Psalm 86:1–6 before the Cordero de Dios (“Lamb of God”/Agnus Dei); (6) Psalm 103:1–2, 4–5, 22 before the Gloria a ti/Comunión (“We Glorify You”/Communion); and (7) Psalm 150 before the final Aleluya (Alleluia). While the poem for the Ofrenda inicial was written by Claudio Giménez, both he and Florentín Giménez collaborated on the texts of the Gloria a ti and the final Aleluya, which is centered on Psalm 117.20Interview with the composer, July 2, 2020. See the Appendix for the original texts and English translation of these three hymns. Each movement of the Mass is based on Paraguayan folk-style music forms and rhythms. Giménez uses the guarania exclusively for the Ofrenda inicial; the Señor, ten piedad; and the Cordero de Dios; and the Paraguayan polca (later designated by Giménez as pupyasy) for the Gloria a ti/Comunión and the Aleluya. Combined forms were also employed for the Gloria (pupyasy and guarania), the Credo (rasguido doble and pupyasy), and the Santo (valseado and pupyasy kyre’ỹ).21While the duple meter rasguido doble (double strumming) is closely related to the rhythmic pattern of the habanera, the Paraguayan valseado refers to a triple-meter-waltz accompaniment pattern. For more information on the rasguido doble, see Shepherd and Horn (2014). For details on the Paraguayan valseado, see Colman (2015, chap. 5) Although soloists are featured throughout all sections of the work, Giménez uses the choir in each movement. Tables 1, 2, and 3 show the overall plan for the Misa folclórica in its different versions.

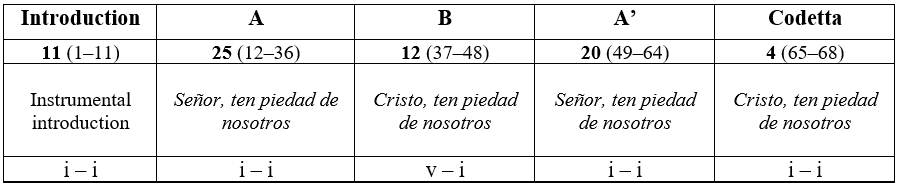

Table 1. Overall plan for the Misa folclórica (1992 version)

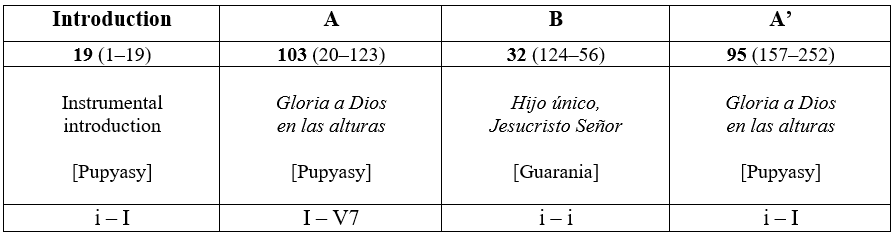

Table 2. Overall plan for the Misa folclórica (2005 version)

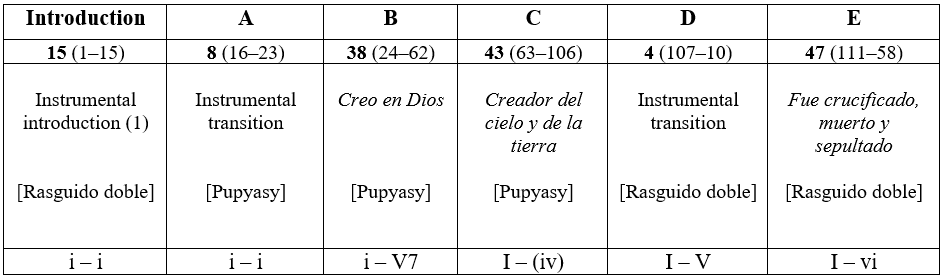

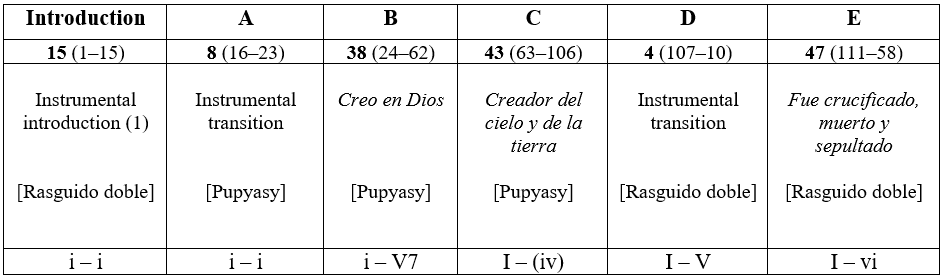

Table 3. Overall plan for the Misa folclórica (2011 version)

By examining the various sections of Giménez’s Mass, we can understand the overall design of the piece, the specific ways in which he uses folk-style musical idioms, and his approach to harmonic and rhythmic motion. Based on the 2011 published score of the work, the following series of tables and musical examples illustrate these points.

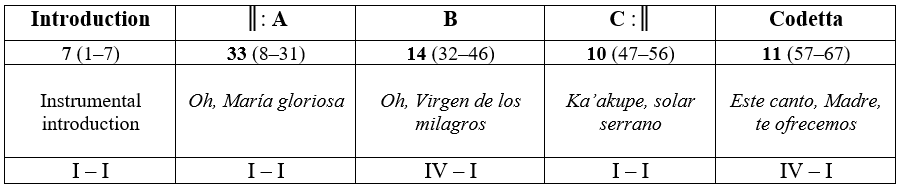

Functioning as an introduction to the Misa folclórica paraguaya—or, in the words of the composer, as a type of Introit, the hymn Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen is a guarania in G major. Giménez divides the poem’s single verse and refrain into four sections in which the first three, A, B, and C, are repeated (Table 4). With brief points of imitation and solo entrances, Giménez situates the music within a homophonic texture. As the composer notes, “An initial offering to the Virgin is part of this Mass. When we performed it at the Basilica [of Caacupé], the premiere [of the piece] became a majestic spiritual moment” (Giménez 2011, unnumbered pages after Obp. 697).

Table 4. Form and main harmonic sequence for the Ofrenda inicial (2011 version)

Señor, ten piedad (“Lord, have mercy”) is a guarania in G minor (Table 5). This movement is primarily consonant in sound and based on the tonic-subdominant-dominant harmonic motion found in traditional guaranias (Example 1). Though the choir starts with the phrase Cristo, ten piedad (“Christ, have mercy”) as a type of accompaniment, which corresponds to the B section, the soloists sing the corresponding text to the A section (Señor, ten piedad). For the B section, Cristo, ten piedad (“Christ, have mercy”), Giménez uses a series of unexpected and controlled dissonances in the context of a harmonic progression that highlights them (Dm–Fm7-5–Cm9–B♭–Fmaj7–B♭–Gmaj7–Cm–B♭maj7/Dmaj7–E♭–Dmaj7–Gm). Finally, using the phrase Cristo, ten piedad from the B section, Giménez adds a four-measure codetta at the end of the C section (Señor, ten piedad).

Table 5. Form and main harmonic sequence for Señor, ten piedad (2011 version)

Example 1. Introduction to the Señor, ten piedad – guarania form (2011 version)

Designed in a ternary form, the Gloria section of the Mass includes a pupyasy in G major (A) with an instrumental introduction in G minor; a guarania in G minor (B); and a pupyasy in G major (A’), with an instrumental transition in G minor preceding it (Table 6). As in the case of Giménez’s instrumental and vocal folkloric pieces where a tendency toward the use of mediant relationships became customary, he features two of his favorite harmonic progressions throughout all the subsections of the Gloria: G–E♭–B♭–C–G and Gm–Cm–Gm–Fmaj7–B♭–E♭–Dmaj7–Gm. For Giménez, this movement—particularly in the use of the pupyasy form—represents one of the highpoints of the entire work.22Interview with the composer, July 2, 2020.

Table 6. Form and main harmonic sequence for the Gloria (2011 version)

Giménez’s Credo alternates sections based on the rasguido doble and pupyasy forms (Table 7). Although the music moves from G minor (Introduction, A, B) to G major (C, D, E) and even to E minor in the final four measures, in reality, in the context of Giménez’s works, the movement is one of the most chromatic of the entire Mass (Example 2). As with the Credo in Ariel Ramírez’s Misa criolla, Giménez incorporates the technique of repetition into the choral parts of his Credo, while having the soloists emphasize the main sections of the text.23A brief reference to the Misa criolla is given in the next section. Throughout the movement, Giménez employs text painting, which is particulary salient in two places, mm. 127–31 (“From there he will come again to judge the living and the dead”) and mm. 140–47 (“the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the dead, and the life everlasting”). In the first instance and in addition to slowing the tempo gradually, Giménez uses the sequence Dmaj7–Dm–Am–F♯dim7–D. For mm. 140–47, he paints the text with the sequence Am–Bmaj7–Emaj7–Amaj7–F♯dim–F♯maj7––F♯dim–Dmaj7–G–Bm7. Finally, a codetta closes the piece with the text Creo, Señor (“Lord, I believe”), while the movement slowly ends in E minor.

Table 7. Form and main harmonic sequence for the Credo (2011 version)

Example 2. Introduction for the Credo – rasguido doble form (2011 version)

The Santo movement not only is cast in a ternary form but also combines two folkloric forms: the triple-meter valseado, and the lively and energetic pupyasy kyre’ỹ or polca paraguaya (Table 8). Throughout the piece and by alternating melodic phrases between choir and soloists, Giménez evokes the effect of multiple voices singing continuous exclamations of the word “Holy.” Typical of valseado accompaniment and in two-measure groupings, Giménez employs continuous melodic sixteenth-note articulations for beats two and three as well as one, two, and three of the following measure, thus rendering the effect of “being” in compound duple meter (Example 3). After an authentic cadence in F Major (m. 69), the composer transitions from valseado to pupyasy kyre’ỹ with no preparation—a common technique used by him in other folk-style musical works (Example 4). One of the most striking harmonic progressions in the piece is found in mm. 123–37 (C), where Giménez uses chromatic mediant relationships and a series of ascending melodic phrases to the text, “Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord” (F–Fmaj7–B♭–Gmaj7–C–F–D♭–A♭–Cmaj7–F). Following mm. 156–59, which evoke the beginning rhythmic sequence in Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus,” the Santo ends with a four-measure codetta.

Table 8. Form and main harmonic sequence for the Santo (2011 version)

Example 3. Introduction for the Santo – valseado form (2011 version)

Example 4. Transition from valseado to pupyasy kyre’ỹ in the Santo – mm. 68–72 (2011 version)

Giménez’s Cordero de Dios is a guarania in G minor (Table 9). Imitating the melodic and harmonic sequence presented in the instrumental introduction, the choir vocalizes it with the syllable “oh” in A, repeats multiple times the phrase Cordero de Dios, danos la paz (“Lamb of God, give us peace”) in B, before the tenor soloist sings the opening line of the prayer in C. During this last section (mm. 66–73), Giménez adds a soprano discant with long-note values, which is reminiscent of the instrumental arranging techniques utilized by composers such as Annunzio Paolo Mantovani (1905–80), Claude Vasori “Caravelli” (1930–2019), and Angel “Pocho” Gatti (1930–2000), among others. In contrast with phrases of controlled dissonance sung by the choir, Giménez presents lyrical lines performed by the tenor soloist. According to him, this particular guarania is one of the two highpoints of the entire work.24The two “highpoints” refer to the Gloria and the Cordero de Dios (interview, July 2, 2020).

Table 9. Form and main harmonic sequence for the Cordero de Dios (2011 version)

Although conceived as a guarania, the constant pizzicato rhythmic accompaniment of the Communion hymn Gloria a ti evokes a slow waltz (Table 10). An instrumental introduction is followed by a second vocal introduction where the choir vocalizes a brief melodic and harmonic sequence on the syllable “oh.” In the tonal area of F major, verse and refrain are repeated once before a six-measure codetta. Designed as a hymn to be sung during communion, Giménez encourages the continuous repetition of the piece as needed.

Table 10. Form and main harmonic sequence for the hymn Gloria a ti (2011 version)

For the final hymn of his “Paraguayan Folkloric Mass,” Giménez employs a lively and highly syncopated pupyasy kyre’ỹ rhythm, as well as a series of brief repetitive melodic phrases and harmonic sequences typically found in Paraguayan folk-style music (Table 11). Based on Psalm 117, this brief text and the continuous repetition of musical phrases in G major highlight the celebratory nature of the hymn. Whereas the hemiola effect is present in other movements of the work using the pupyasy, polca, or kyre’ỹ rhythms, Giménez accentuates it in this final piece. A specific example of his emphasis on hemiola is found in A (mm. 29–35) of the Aleluya (Example 5).

Table 11. Form and main harmonic sequence for the hymn Aleluya (2011 version)

Example 5. Section A (mm. 29–35) from the hymn Aleluya – pupyasy kyre’ỹ form (2011 version)

Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya was premiered on September 8, 1992 at the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Miracles of Caacupé.25Generally speaking, the name of the city could be spelled either in Guaraní (Ka’akupé) or Spanish (Caacupé). In addition to soloists Ana María Casamayouret (soprano), Adriana Barreto (mezzo-soprano), Emiliano González (tenor), and Luis González (baritone), Giménez conducted Las voces del tiempo, a folkloric ensemble, and a choir and chamber orchestra. Paraguayan actor Mario Prono served as reader for the Psalms (Image 1).

Image 1. Photo of the first performance of Misa folclórica paraguaya. Caacupé, Paraguay, 1992. (personal copy)

In 1992, the Misa folclórica paraguaya was recorded and released by Discos Cerro Corá.26The 1992 original recording did not include the Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen, which appeared as part of the Misa folclórica in the 2005 recording and 2011 publication of the score. Both the 1992 recording and the 1998 re-release began with the reading of Psalm 31. See Giménez (1992). Six years later, the recording was reissued as part of a two-volume anthology produced by Giménez and released by Discos Elio (Giménez 1998). In 2005, along with Giménez’s Suite Mangoré for guitar and chamber orchestra, Misa folclórica paraguaya, now with the inclusion of the hymn Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen, was reissued and released by Guairá Producciones (Giménez 2005). In addition to the 1992 premiere and numerous presentations in the interior of the country, the city of Encarnación, the parish churches of Cristo Rey and Sagrado Corazón de Jesús—“Salesianito”—in Asunción, notable performances of Giménez’s Mass included those at the Catedral Basílica of Caacupé in 2005 and at the Capilla Jardín la Paz in Asunción in 2009.27Conducted by Giménez, the concert on September 9, 2005 in Caacupé included: (1) soloists Ada Antúnez (soprano), Estefana Galeano (mezzo-soprano), Pablo López (tenor), and César González (baritone); (2) the Emiliano Aiub Conjunto folclórico; (3) a chamber orchestra; and (4) the Coro Polifónico del Conservatorio Nacional de Música (Manuel Cabral, conductor). With María Alejandra Velázquez at the pódium, the performance on September 27, 2009 in Asunción included soloists, the Conjunto folclórico y Coro Polifónico del Conservatorio Nacional de Música (Benito Román and María Alejandra Cabrera, conductors), and the Camerata “Lara Bareiro” chamber orchestra—all performing ensembles of the National Conservatory of Music, CONAMU. Revised and expanded by Giménez, Misa folclórica paraguaya was published in 2011 as part of his Cancionero V.28While the introduction to the Ofrenda inicial for the 2005 recording included only 2 measures, the 2011 published version included 8 additional ones to the introduction and 2 punctuations of G-major chords at the end of the hymn. Giménez also added 16 measures to the instrumental introduction to the guarania for Cordero de Dios (the previous instrumental introduction was 9 measures in length) and 10 measures to the instrumental introduction to Gloria a Ti (the previous introduction was 1 1/2 measures in length).

Other Paraguayan and Latin American Folkloric Masses

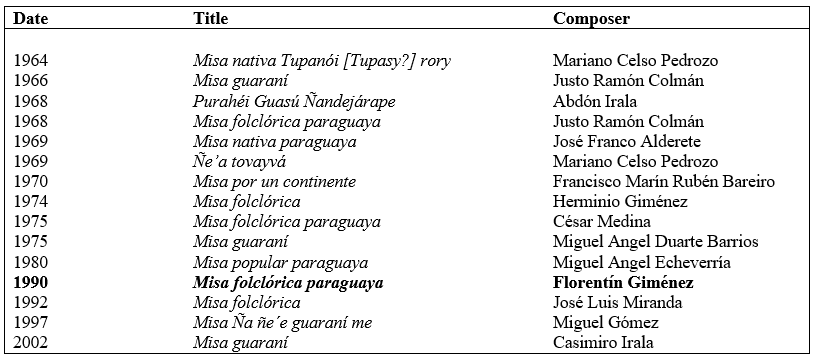

Giménez’s musical setting of the Mass is not the only one by a Paraguayan composer. Since Vatican II, at least fifteen other folkloric musical settings of the Mass have been composed by various Paraguayan musicians between 1964 and 2002 (Table 12).29I am indebted to Alvaro Morel Aquino for graciously sharing his research (Morel Aquino 2009) on Paraguayan folkloric masses (including the summary presented in Table 12). Besides Morel, see Pedrozo (2003) and Szarán (1997).

Table 12. Musical settings of the Mass composed by Paraguayan composers30While some of the Paraguayan folkloric masses include texts in Spanish, others feature versions in Guaraní. Settings in Spanish include: (1) Colmán’s Misa guaraní (1966) and Misa folclórica paraguaya (1968); (2) Marín and Bareiro’s Misa por un continente (1970); (3) H. Giménez’s Misa folclórica (1974); (4) Medina’s Misa folclórica paraguaya (1975); (5) Echeverría’s Misa popular paraguaya (1980); (6) F. Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya (1990); and (7) Miranda’s Misa folclórica (1992). Settings in Guaraní include: (1) Pedrozo’s Misa nativa Tupanói [Tupasy?] rory (“Native Mass A Joyful Blessing”) (1964) and Ñe’a tovayvá (“Words of Supplication”) (1969); (2) Irala’s Purahéi Guasú Ñandejárape (“Grand Song to Our Lord”) (1968); (3) Duarte’s Misa guaraní (1975); (4) Goméz’s Misa Ña ñe´e guaraní me (“Mass in Our Guaraní Language”) (1997); and (5) Irala’s Misa guaraní (2002).

Musically speaking, all of these settings are connected through the use of folkloric rhythmic forms, mainly the guarania and the polca paraguaya. According to Morel, it is not uncommon to attend Mass in Paraguay and listen to a combination of sections by various composers—for instance, the Kyrie by Abdón Irala, the Gloria and Agnus Dei by José Franco, and the Sanctus by either José Franco or Herminio Giménez.31Interview with Alvaro Morel, October 2, 2019. Of all these Paraguayan folkloric masses, the settings by Herminio Giménez and Florentín Giménez denote the highest degree of musical sophistication, informed by the training and experience of both composers in the development of significant folkloric and concert works.

In comparison to other Latin-American musical settings of the Mass, Florentín Giménez’s piece shares a similar approach in the use of traditional forms and rhythms from various countries. One of the first in this group was the Misa criolla by Argentinian composer Ariel Ramírez (1921–2010), which was written after the Second Vatican Council (1962), first recorded in 1965, and premiered in 1967. Ramírez’s piece inspired Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya.32In an interview conducted on June 24, 2020, Giménez asserted: “I studied it carefully, …I memorized the score to the Mass by Ramírez, and I was inspired by that piece to compose the ‘Paraguayan Folkloric Mass.’” As one of the most widely performed and recorded Latin-American folk masses, Ramírez’s setting of the Ordinary uses Argentinian regional folk rhythms, such as the chacarera, carnavalito, and baguala.33For a definition of the Argentinian chacarera, carnavalito, and baguala, see Shepherd and Horn (2014). Besides the Misa criolla and among numerous folkloric masses composed throughout Latin America, three particular settings have been recognized as representing their countries: (1) the 1964 Misa folclórica colombiana by priest Rubén Darío Vanegas Montoya (1942–2015), which includes Colombian rhythms, such as the bambuco, porro, and cumbia; (2) the 1966 La misa panamericana (or “Mariachi Mass”), which presents regional musical forms such as the Mexican jarabe (tapatío), canción ranchera, and son; and (3) the 1980 Misa popular salvadoreña by Guillermo Cuéllar Barandiarán (b. 1955), which includes traditional Salvadoran rhythms, such as the cumbia, ranchera, and chanchona.34Commissioned by the Bishop of Cuernavaca, Mexico, Sergio Méndez Arceo (1907–92) and composed by Canadian priest Juan Marco Leclerc in 1966, La misa panamericana [“The Pan-American Mass”] was written in the style of a mariachi folk mass. Whereas other “mariachi masses” appear to have been regularly composed since then, La misa panamericana has remained the standard for mariachi groups in Catholic churches. In fact, though the Cathedral of the Ascension in Cuernavaca has been the home of the mariachi mass in Mexico for more than 50 years, St. Joseph Catholic Church in Houston, Texas is the only parish in the United States to perform La misa panamericana continuously since 1967 (Favinger 2015, 54).

In the Ordinary of his Misa folclórica colombiana, Rubén Darío Vanegas Montoya uses Colombian folkloric and regional rhythms. First introduced at the Iglesia de La Porciúncula in Bogotá in 1964, this Mass was received in the midst of both praise and controversy. Offering context and in reference to Vanegas Montoya’s “Colombian Folkloric Mass,” journalist Juan Carlos Díaz Martínez (2012) writes: “The Mass that the [Colombian] Catholic people celebrate with enthusiasm today . . . was the object of severe criticism almost fifty-years ago. . . .”

Written at the request of Monseñor Oscar Romero (1917–80), and with theological advice provided by Augustinian priest Plázido Erdozaín (1935–2017), anthropologist and singer-songwriter Guillermo Cuéllar composed his Misa popular salvadoreña. See Afflicted with Hope (2015). “Story of Guillermo Joaquin Cuellar Barandiaran,” embracingelsalvador.org, accessed June 26, 2020, https://www.embracingelsalvador.org/guillermo-cuellar-2/.

For a description of the various musical forms and rhythms from Colombia (bambuco, porro, and cumbia), Mexico (jarabe tapatío, canción ranchera, and son), and El Salvador (cumbia and ranchera), see Shepherd and Horn (2014). And for a brief introduction to the Salvadoran chanchona, see Sheehy (2011).

Conclusion

Giménez’s Misa folclórica shows productivity in the sphere of Paraguayan folkloric musical composition and introduces audiences to the composer’s musical nationalism in relation to other Paraguayan and Latin-American folkloric settings of the Mass. While Paraguayan cultural themes (i.e., folkloric music idioms, Guaraní culture, and nationalism) have informed the Misa folclórica and other works by Giménez, in reality they are critical to his compositional aesthetic. In a word, he considers his musical output as a means and signifier used to describe and prescribe, musically speaking, how socially embedded Paraguayan cultural beliefs must be represented, preserved, and transmitted. Though Giménez did not include texts in Guaraní as part of his folkloric Mass, he stressed the significance and influence of Guaraní culture in the (re)designation of a Paraguayan musical form used in the various sections of the 2011 version of the work—specifically, pupyasy and pupyasy kyre’ỹ replacing polca paraguaya or polca.

Along with the “Paraguayan Folkloric Mass,” Giménez’s concert music and other folk-style music compositions function as a lens through which we may observe and evaluate his beliefs and legacy as a Paraguayan composer. At the same time, Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya represents a significant turning point in his career. The work not only became part of the first group of concert pieces composed by Giménez during his first year as a “composer in residence,” but around the time the work premiered and during the decade of the 1990s, he devoted himself to music education and research in order to defend and promote Paraguayan music. As we have observed, Giménez’s use and combination of a variety of Paraguayan musical forms and rhythms in the Misa folclórica paraguaya illustrate the view that the integration of Paraguayan music with the liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church is the ideal way to transmit a cultural identity that celebrates the composer’s view of the sacred in the context of a Paraguayan nationalism.

Notes

1. This article constitutes one of the first musicological publications in English on the music of Paraguayan composer Florentín Giménez. The author presented a conference paper related to this topic at the 2019 Fall Meeting of the Southwest Chapter of the American Musicological Society. I am grateful to Mr. Giménez, who kindly shared with me recordings of his folkloric mass, as well as the published version of the score. I would also like to acknowledge Adam Cogliano for his timely assistance with the musical notation and transcription of selected sections of the Mass. Unless indicated otherwise, all English translations are mine. Finally, I have included a Glossary of key terms and their definitions.

2. Throughout this article, I use “folk-style music” instead of “folk music,” since the former term better describes the compositional style of Giménez, whereas the latter one implies music deriving from oral traditions and reflecting anonymous authorship.

3. Although the topic of Paraguayan folkloric Masses stands out as one of the numerous musicological lacunae in Paraguayan music research, the intention of the present paper is to fill that void partially by discussing Florentín Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya. Because this study’s main focus is the work by Giménez, a detailed discussion of other Paraguayan folkloric masses is outside the scope of this paper. Fortunately, besides brief references to a few of these works in publications by Pedrozo (2003) and Szarán (1977), Alvaro Morel’s research on Herminio Giménez’s 1974 Misa folclórica (2009) provides a concrete background on Herminio Giménez’s work as well as context and information regarding others.

4. The biographical sketch is based on the composer’s memoir. See Florentín Giménez (2008).

5. According to Giménez, in addition to a vocalist, an orquesta típica may include two or more bandoneones, one or more violins, a double bass, and a piano, usually played by the leader of the ensemble. While the polca paraguaya or simply polca—sometimes also referred to as kyre’ỹ and in certain contexts as galopa—is a lively song and dance form in compound duple meter with sesquialtera/hemiola rhythmic characteristics, the guarania is its slow and relaxed song-form counterpart. In general, both the Paraguayan polca and the guarania exhibit repetitive musical phrases and a harmonic vocabulary derived from tonic-dominant-subdominant relationships. Typically, the guitar and diatonic harp—as well as the accordion, violin, and double bass or electric bass nowadays—accompany Paraguayan polcas and guaranias. For more information on these musical genres, see Alfredo Colman (2014).

6. Composed in 1956, Giménez and Molar’s Muy cerca de ti (“Very Close to You”) became an “overnight success” and was recorded by artists such as Argentinian jazz composer Angel “Pocho” Gatti, singers Roberto Yanés and Estela Raval, Brazilian pianist Daniel Salinas and singer Martha Mendonça, the Mexican Trío Los Panchos, numerous Paraguayan soloists and conjuntos (vocal ensemble accompanied by two guitars or two guitars and a harp), and US American singers Freddie Davis and Andy Russell, among others.

7. In addition to monographs addressing Paraguayan music and culture—La música paraguaya (1997), Rasgos tradicionales del folklore paraguayo (1999), and El Decálogo sonoro (2017), Giménez has published a memoir entitled Historia sin tiempo (2008, revised in 2013) and a series of four novels: (1) Indalecio (2007, 2009), (2) Rasgos y pasiones (2007), (3) Isabela (2010, 2012), and (4) Samunko (2010, 2017). For full details, see the Reference list at the end of this article.

8. The honorary doctorates have been conferred by the Universidad Nacional de Asunción (2006), the Universidad Metropolitana de Asunción (2007), and the Universidad Nacional de Pilar (2014). Giménez received the Premio Nacional Música in 2001 and in 2015, the first time for his Sinfonía No. 1 en Re Menor “Metamorfosis,” and the second time for his opera, Juana de Lara.

9. For a detailed discussion on the topic of paraguayidad, see chapters 1 (“On Identity, Paraguayidad, and Tekó”) and 2 (“Paraguayidad and Paraguayan Identity”) in Colman (2015).

10. Lamenting the lack of musical understanding among the majority of current Paraguayan musical performers, Giménez has also addressed this particular issue on radio, television, and in newspaper interviews, as well as through interactions on social media.

11. For instance, Giménez produced studio recordings of his arrangements of traditional music (Tierra de guaranias and Inédita 12 [1979]), and with the chamber ensemble Camerata Asuncena, in 1981 and 1982 he recorded a series of television broadcasts highlighting Paraguayan folk-style music.

12. Curiously, starting with the third Cancionero (2011), the lively songs earlier labeled [Paraguayan] polcas have been referred to and published under this new designation.

13. Whereas other Paraguayan composers and performers have employed the term pupyasy, polca paraguaya or polca still remains the preferred designation for the general public.

14. In his 2008 memoir (337–53), Giménez provides a vivid account of the circumstances and events leading to his dismissal from the Asunción Symphony. During my interview with the composer on June 24, 2020, he indicated that one of the reasons behind his dismissal was the accusation that he was a supporter of the regime of President Alfredo Stroessner, which was ended by a military coup d’etat in February 1989. In the words of Giménez, “[w]hen Stroessner’s government fell, I was accused of being a stronista.”

15. During the same interview, Giménez stated that “I was deeply hurt after what they have done to me, then that motivated me to compose the Mass as a personal prayer.”

16. Played with a soft-headed mallet and a stick, the bombo is a double-headed drum covered with the cured skin of animals (goat, cow, or sheep). In this particular case, conjunto folclórico refers to a vocal ensemble with four singers accompanied by two guitars.

17. Celebrated on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary (December 8), “Our Lady of the Miracles of Caacupé” has been consecrated as the Patron and Lady Protector of Paraguay. Though Caacupé (the town) was founded on April 4, 1770, a chapel was dedicated to the Virgen de Caacupé in 1769. For more details, see “Caacupé: el santuario, la leyenda y la imagen de la patrona de Paraguay,” Catholic.net, accessed June 23, 2020, https://es.catholic.net/op/articulos/60421/cat/99/caacupe-el-santuario-la-leyenda-y-la-imagen-de-la-patrona-de-paraguay.html#modal.

18. The historical background and social development of the concept of música folclórica and the closely related folklore de proyección have also been studied by specialists analyzing the folk-style music of other Latin American countries. See Florine (2016), Rodríguez (1986, 1989, 2001, 2013, 2018), and others.

19. The 1992 score did not include the Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen as part of the Misa folclórica paraguaya. Instead, it appeared for the first time in the 2005 recording version.

20. Interview with the composer, July 2, 2020. See the Appendix for the original texts and English translation of these three hymns.

21. While the duple meter rasguido doble (double strumming) is closely related to the rhythmic pattern of the habanera, the Paraguayan valseado refers to a triple-meter-waltz accompaniment pattern. For more information on the rasguido doble, see Shepherd and Horn (2014). For details on the Paraguayan valseado, see Colman (2015, chap. 5)

22. Interview with the composer, July 2, 2020.

23. A brief reference to the Misa criolla is given in the next section.

24. The two “highpoints” refer to the Gloria and the Cordero de Dios (interview, July 2, 2020).

25. Generally speaking, the name of the city could be spelled either in Guaraní (Ka’akupé) or Spanish (Caacupé).

26. The 1992 original recording did not include the Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen, which appeared as part of the Misa folclórica in the 2005 recording and 2011 publication of the score. Both the 1992 recording and the 1998 re-release began with the reading of Psalm 31. See Giménez (1992).

27. Conducted by Giménez, the concert on September 9, 2005 in Caacupé included: (1) soloists Ada Antúnez (soprano), Estefana Galeano (mezzo-soprano), Pablo López (tenor), and César González (baritone); (2) the Emiliano Aiub Conjunto folclórico; (3) a chamber orchestra; and (4) the Coro Polifónico del Conservatorio Nacional de Música (Manuel Cabral, conductor). With María Alejandra Velázquez at the pódium, the performance on September 27, 2009 in Asunción included soloists, the Conjunto folclórico y Coro Polifónico del Conservatorio Nacional de Música (Benito Román and María Alejandra Cabrera, conductors), and the Camerata “Lara Bareiro” chamber orchestra—all performing ensembles of the National Conservatory of Music, CONAMU.

28. While the introduction to the Ofrenda inicial for the 2005 recording included only 2 measures, the 2011 published version included 8 additional ones to the introduction and 2 punctuations of G-major chords at the end of the hymn. Giménez also added 16 measures to the instrumental introduction to the guarania for Cordero de Dios (the previous instrumental introduction was 9 measures in length) and 10 measures to the instrumental introduction to Gloria a Ti (the previous introduction was 1 1/2 measures in length).

29. I am indebted to Alvaro Morel Aquino for graciously sharing his research (Morel Aquino 2009) on Paraguayan folkloric masses (including the summary presented in Table 12). Besides Morel, see Pedrozo (2003) and Szarán (1997).

30. While some of the Paraguayan folkloric masses include texts in Spanish, others feature versions in Guaraní. Settings in Spanish include: (1) Colmán’s Misa guaraní (1966) and Misa folclórica paraguaya (1968); (2) Marín and Bareiro’s Misa por un continente (1970); (3) H. Giménez’s Misa folclórica (1974); (4) Medina’s Misa folclórica paraguaya (1975); (5) Echeverría’s Misa popular paraguaya (1980); (6) F. Giménez’s Misa folclórica paraguaya (1990); and (7) Miranda’s Misa folclórica (1992). Settings in Guaraní include: (1) Pedrozo’s Misa nativa Tupanói [Tupasy?] rory (“Native Mass A Joyful Blessing”) (1964) and Ñe’a tovayvá (“Words of Supplication”) (1969); (2) Irala’s Purahéi Guasú Ñandejárape (“Grand Song to Our Lord”) (1968); (3) Duarte’s Misa guaraní (1975); (4) Goméz’s Misa Ña ñe´e guaraní me (“Mass in Our Guaraní Language”) (1997); and (5) Irala’s Misa guaraní (2002).

31. Interview with Alvaro Morel, October 2, 2019.

32. In an interview conducted on June 24, 2020, Giménez asserted: “I studied it carefully, …I memorized the score to the Mass by Ramírez, and I was inspired by that piece to compose the ‘Paraguayan Folkloric Mass.’”

33. For a definition of the Argentinian chacarera, carnavalito, and baguala, see Shepherd and Horn (2014).

34. Commissioned by the Bishop of Cuernavaca, Mexico, Sergio Méndez Arceo (1907–92) and composed by Canadian priest Juan Marco Leclerc in 1966, La misa panamericana [“The Pan-American Mass”] was written in the style of a mariachi folk mass. Whereas other “mariachi masses” appear to have been regularly composed since then, La misa panamericana has remained the standard for mariachi groups in Catholic churches. In fact, though the Cathedral of the Ascension in Cuernavaca has been the home of the mariachi mass in Mexico for more than 50 years, St. Joseph Catholic Church in Houston, Texas is the only parish in the United States to perform La misa panamericana continuously since 1967 (Favinger 2015, 54).

In the Ordinary of his Misa folclórica colombiana, Rubén Darío Vanegas Montoya uses Colombian folkloric and regional rhythms. First introduced at the Iglesia de La Porciúncula in Bogotá in 1964, this Mass was received in the midst of both praise and controversy. Offering context and in reference to Vanegas Montoya’s “Colombian Folkloric Mass,” journalist Juan Carlos Díaz Martínez (2012) writes: “The Mass that the [Colombian] Catholic people celebrate with enthusiasm today . . . was the object of severe criticism almost fifty-years ago. . . .”

Written at the request of Monseñor Oscar Romero (1917–80), and with theological advice provided by Augustinian priest Plázido Erdozaín (1935–2017), anthropologist and singer-songwriter Guillermo Cuéllar composed his Misa popular salvadoreña. See Afflicted with Hope (2015). “Story of Guillermo Joaquin Cuellar Barandiaran,” embracingelsalvador.org, accessed June 26, 2020, https://www.embracingelsalvador.org/guillermo-cuellar-2/.

For a description of the various musical forms and rhythms from Colombia (bambuco, porro, and cumbia), Mexico (jarabe tapatío, canción ranchera, and son), and El Salvador (cumbia and ranchera), see Shepherd and Horn (2014). And for a brief introduction to the Salvadoran chanchona, see Sheehy (2011).

Appendix 1: Texts and Translation to Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen, Gloria a ti, and Aleluya

|

Ofrenda inicial a la Virgen |

|

| Oh, María gloriosa de los cerros floridos, en tu mirada piadosa hallamos fe y bendición. Oh, Virgen de los milagros a ti llegamos con júbilo, implorando por tu amor y en pos de tu bendición. Ka’akupé solar serrano, Ka’akupé pueblo de amor. Este canto, Madre, te ofrecemos con amor. |

O, Glorious Mary of the blooming hills, In your pious gaze we find faith and blessing. O, Virgin of the miracles, with joy we come to you, Imploring your love and seeking your blessing. Ka’akupé, sunny mountain range, Ka’akupé, town of love. This song, Mother, We offer you with love. |

|

|

|

| Gloria a ti por el pan que tú has dado, alabanzas sin fin por tu amor. Por el cielo y los mil colores, Por el valle, el cerro y el mar. Gloria a ti por las flores, Gloria a ti por los prados. Gloria, Gloria, Gloria a ti. |

We glorify you for the bread that you have given, Endless praises for your love. For the sky and a thousand colors, For valley, hill, and sea. We glorify you for the flowers, We glorify you for the prairies. Glory, Glory, We glorify you. |

|

|

|

| Alabad al Señor, todas las naciones, Aleluya. Entonad vuestras alabanzas, Aclamad vuestras concordias en alegría. |

Praise the Lord, all nations, Alleluia. Sing your praises, Hail your harmonies in joy. |

Appendix 2: Glossary

cancionero: songbook

conjunto: a vocal ensemble accompanied by two guitars or two guitars and a harp

galopa: a dance form in two sections and in compound duple meter with hemiola rhythmic characteristics

gaucho: a skilled cowboy of the Argentine pampas (grasslands) known for his bravery. A symbol of Argentine cultural identity

guarania: a slow and relaxed urban song form in compound duple meter with hemiola rhythmic characteristics

kyre’ỹ: Guaraní for “lively.” A song and dance form in compound duple meter with hemiola rhythmic characteristics

Misa criolla: Argentinian folkloric mass (1965?) by Ariel Ramírez

Misa folclórica colombiana: Colombian folkloric mass composed in 1964 by priest Rubén Darío Vanegas Montoya

Misa folclórica paraguaya: Paraguayan folkloric mass composed in 1990 by Florentín Giménez

La misa panamericana: The Panamerican mass or “Mariachi Mass” composed in 1966 by priest Juan Marco Leclerc

Misa popular salvadoreña: Salvadoran popular mass composed in 1980 by Guillermo Cuéllar Barandiarán

música folclórica: a composed type of Paraguayan urban music that has been inspired by folk-style music idioms and depicts strong sentiments of cultural identity

música popular: see música folclórica

obras populares: popular musical works

orquesta típica: tango orchestra

Paraguayan zarzuelas: Paraguayan musical comedies

paraguayidad: Paraguayan-ness

polca paraguaya: a lively song and dance form in compound duple meter with hemiola rhythmic characteristics

pupyasy: a compound word in Guarani coined by Florentín Giménez in 2007 to re-designate the term polca paraguaya

rasguido doble: literally, “double strumming.” A song form in duple meter with connections to the rhythmic accompaniment of the Habanera

tekó: Guaraní for the “[Paraguayan] way of being”

valseado: waltz

References

Afflicted with Hope. 2015. “Story of Guillermo Joaquin Cuellar Barandiaran.” July 1, 2015. Accessed June 26, 2020. embracingelsalvador.org. https://www.embracingelsalvador.org/guillermo-cuellar-2/.

Añazco, Celsa y Rosalba Dendia. 1997. Identidad Nacional. Aportes para una reforma educativa. Asunción: CIDSEP (Centro Interdisciplinario de Derecho Social y Economía Política).

Avelar, Idelber and Christopher Dunn. 2011. “Music as Practice of Citizenship in Brazil.” In Brazilian Popular Music and Citizenship, edited by Idelber Avelar and Christopher Dunn, 1–27. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Béhague, Gerard. 1979. Music in Latin America: An Introduction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.

Boettner, Juan Max. 1997. Música y Músicos del Paraguay. 1956. Reprint, Asunción: BGS/FA-RE-MI Paraguay.

Cardozo Ocampo, Mauricio. 2005. Mundo Folklórico Paraguayo. Primera Parte: Paraguay Folklórico. 1982. Reprint, Asunción: Atlas Representaciones.

Celso Pedrozo, Mariano. 2003. La religiosidad paraguaya y la identidad nacional Asunción: Imprenta Salesiana.

Colman, Alfredo. 2014. “Guarania” and “Polca paraguaya.” In The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, edited by John Shepherd and David Horn, vol. 9. Genres: Caribbean and Latin America. London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

———. 2015. The Paraguayan Harp: From Colonial Transplant to National Emblem. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Dahlhaus, Carl. 1989. “Nationalism and folk music” and “On the aesthetics of national expression in music.” In Between Romanticism and Modernism: Four Studies in the Music of the Later Nineteenth Century, translated by Mary Whittall, 90–102. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Díaz Martínez, Juan Carlos. 2012. “La primera misa folclórica en Colombia cumple 50 años.” El Tiempo, April 6, 2012. Accessed June 26, 2020. eltiempo.com. https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-11512441.

Favinger, Sarah. 2015. “American Diversity and the Genesis of Mass Settings following the Second Vatican Council: A Case Study of Mary Lou’s Mass and La misa panamericana.” MM thesis, Baylor University.

Fernández L’Hoeste, Héctor and Pablo Vila, editors. 2018. Sound, Image, and National Imaginary in the Construction of Latin/o American Identities. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Florine, Jane. 2016. El duende musical y cultural de Cosquín, el Festival Nacional de Folklore argentino. Buenos Aires: Editorial Dunken.

Giménez, Florentín. 1992. Misa folklórica paraguaya. Asunción: Discos Cerro Corá, compact disc.

———. 1997. La música paraguaya. Asunción: El Lector.

———. 1998. Antología Sinfónica. 2 vols. Asunción: Discos Elio, 10 compact discs.

———. 1999. Rasgos tradicionales del folklore paraguayo. Asunción: Editorial Tavaroga.

———. 2005. Misa folklórica paraguaya. Asunción: Guairá Producciones, compact disc.

———. [2007]. Rasgos y pasiones. Asunción: Editorial Tavaroga.

———. 2007, 2009. Indalecio. Asunción: Editorial Tavaroga.

———. 2008. Historia sin tiempo. Asunción: Editorial Salemma.

———. 2010/2012. Isabela. Asunción: Editorial Tavaroga.

———. (2010), 2017. Samúnko. Solaro con los dioses aterrados. Asunción: Editorial Tavaroga.

———. 2011. Cancionero V. Asunción: Editorial Tavaroga.

———. 2017. El decálogo sonoro. Asunción: Editora Litocolor SRL.

González Rodríguez, Juan Pablo. 1986. “Hacia el Estudio Musicológico de la Música Popular Latinoamericana,” Revista Musical Chilena XL, no. 165: 59–84.

———. 1989. “‘Inti-Illimani and the Artistic Treatment of Folklore.’” Latin American Music Review 10, no. 2 (Fall/Winter): 267–86.

———. 2001. “Musicología popular en América Latina: Síntesis de sus logros, problemas y desafíos,” Revista Musical Chilena LV, no. 195: 38–64.

———. 2013. Pensar la música desde América Latina. Buenos Aires: Gourmet Musical Ediciones.

———. 2018. Thinking about Music from Latin America. Issues and Questions. Translated by Nancy Morris. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Hall, Stuart and Paul du Gay, eds. 1996. Questions of Cultural Identity. London: Sage.

Hall, Stuart, David Held, Don Hubert, and Kenneth Thompson, eds. 1996. Modernity: An Introduction to Modern Societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Herder, Johann Gottfried and Philip V. Bohlman. 2017. Song Loves the Masses: Herder on Music and Nationalism. Translated by Philip V. Bohlman. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hess, Carol A. 2013. Representing the Good Neighbor: Music, Difference, and the Pan American Dream. New York: Oxford University Press.

Itzigsohn, José and Matthias vom Hau. 2016. “Unfinished Imagined Communities: States, Social Movements, and Nationalism in Latin America.” Theory and Society 35, no. 2: 193–212.

Meliá, Bartomeu. 1997. El Paraguay inventado. Asunción: Centro de Estudios Paraguayos “Antonio Guasch.”

Morel Aquino, Alvaro. 2009. “Un análisis de la misa folklórica de Herminio Giménez.” Trabajo final de grado, Licenciatura en Música. Universidad Evangélica del Paraguay.

Morel, Alvaro. editor. 2011. Otras historias de la independencia. Asunción: Santillana, S.A.

Mularski, Jedrek. 2014. Music, Politics, and Nationalism in Latin America: Chile during the Cold War Era. Cambria Studies in Latin American Literatures and Cultures Series. Edited by Román de la Campa, 1-67. Amherst, New York: Cambria Press.

Pérez Montfort, Ricardo. 2008. “Folkloric Studies and the Forging of National Stereotypes in Latin America, 1920–1970: Four Case Studies.” In Hybrid Americas: Contacts, Contrasts, and Confluences in New World Literatures and Cultures, edited by Josef Raab and Martin Butler, 161–90. Inter-American Perspectives, vol. 2. Münster: LIT; Tempe, AZ: Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe.

Prieto, Justo. 1951. Paraguay, La Provincia Gigante de las Indias (Análisis espectral de una pequeña nación mediterránea). Buenos Aires: Librería El Ateneo Editorial.

Sheehy, Daniel E. 2011. “What Makes a Good Smithsonian Folkways Recording?: The Sound and Story of the Salvadoran Chanchona.” Smithsonian Folkways Magazine (Fall/Winter). Accessed June 26, 2020. folkways.si.edu. https://folkways.si.edu/magazine-fall-winter-2011-what-makes-good-folkways-recording-sound-story-salvadoran-chanchona/latin-world/music/article/smithsonianhttps://folkways.si.edu/magazine-fall-winter-2011-what-makes-good-folkways-recording-sound-story-salvadoran-chanchona/latin-world/music/article/smithsonian.

Shepherd, John and David Horn, eds. 2014. The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, vol. 9. Genres: Caribbean and Latin America. London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. 2014.

Szarán, Luis. 1997. Diccionario de la música en el Paraguay. Asunción: Szarán La Gráfica.

Telesca, Ignacio y Carlos Gómez Florentín, editors. 2018. Historia del Paraguay. Nuevas perspectivas. Comité Paraguayo de Ciencias Históricas. Asunción: Editorial Servilibro.

Turino, Thomas. 2003. “Nationalism and Latin American Music: Selected Case Studies and Theoretical Considerations.” Latin American Music Review 24, no. 2 (Fall/Winter) 169–209.

Velázquez Seiferheld, David. 2018. “Anticomunismo y educación en el Paraguay. Las cartillas nacionalista y anticomunista – 1937/1938.” In Historia del Paraguay: Nuevas perspectivas, edited by Ignacio Telesca and Carlos Gómez Florentín, 57–93. Comité Paraguayo de Ciencias Históricas. Asunción: Editorial Servilibro.

Wade, Peter. 2001. “Racial Identity and Nationalism: A Theoretical View from Latin America.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 24, no. 5: 845–65.

Wong, Ketty. 2004. Luis Humberto Salgado: Un Quijote de la música. Quito: Editorial Pedro Jorge Vera, CCE.