Abstract

Musicians increasingly operate in a global community connected by the internet that has affected performance, composition, and listening habits. Similarly, there is a growing trend of publishing scholarly research “open access,” meaning it is online for anyone to read at no cost. Open-access advocates have argued that open access makes possible a global community of scholarship. However, few studies have measured the impact of open-access scholarship and whether it has actually realized the dream of a truly global discourse. To answer this question, this article presents a comprehensive survey of trends in open-access music scholarship by examining 189 open-access music journals. Ultimately, the data suggests that although open-access music journals have made a great deal of research available to a global audience, the journals themselves reflect economic and cultural power imbalances in global academic culture; a majority of open-access music journals are based in either Europe or the United States. Consequently, open-access journals have created an echo chamber in which largely Western perspectives dominate, and in which other perspectives are muted. The article closes with recommendations about how open-access music journals can help realize their potential for global discourse.

Vincent P. Benitez

Introduction

Modern musical culture has been defined by the emergence of global connections among musically active people—whether they are listeners, performers, composers, educators, or researchers. With the rise of the internet, international dialogue becomes easier to imagine and create in practice, and its effects are everywhere. Previously unimaginable amounts of music are readily available for listeners via platforms such as Spotify, and performers and composers have developed new levels of cross-cultural collaboration. Musicians across the globe can sample and remix each other’s music, and online ensembles can perform virtually, creating global communities of performers and listeners (see Whitacre 2021).

If listeners, performers, and composers have already demonstrated ways of engaging with music globally, educators and researchers are lagging behind, especially in the United States. Despite the fact that Western European musical traditions are only one strand of the world’s music, they dominate academic music instruction in the United States (Sarath 2016, 5; Kajikawa 2019, 156–58). Music research (e.g., music history, theory, education) also remains largely focused on traditions from Western Europe and the United States. Although ethnomusicology has done much to redress this situation, it is often treated as a supplemental area of study in music programs in the United States (Sarath 2016, 3, 13; Maus 2004). This academic disconnect from global trends in music has led to warnings that the current form of music instruction may become obsolete (Sarath 2016, iii) and lead to a limited worldview and skill set (Kajikawa 2019, 157).

Although listeners can access millions of songs at the click of a mouse, scholarly research remains surprisingly inaccessible. It is tempting to imagine a global exchange of scholarly research on all aspects of music that parallels the range and speed of exchanges already occurring between listeners and creators. Such a global dialogue could provide a special benefit to the more interpretative fields of music scholarship (music history, ethnomusicology, music theory) that are shaped by the training, analytical outlook, and cultural perspectives of individual researchers as much as they are by data. A global discourse on these subjects would not only offer a multiplicity of new perspectives but also encourage greater understanding and sympathy for the music of other cultures. In addition, it might provide a way for music educators in the United States to develop globally informed pedagogies that engage with a greater variety of the world’s music, and it might create a truer understanding of how different musical cultures look from the inside. Finally, it could help the general public to more directly engage with a variety of scholarship from around the world—a crucial benefit, given the recent decline of professional music criticism in the United States.

Since the turn of the present century, there has been a growing trend of publishing scholarly research (e.g., articles, books, datasets) online for anyone to read at no cost. Open access, it should be noted, is defined by the act of making research available to the general public; reputable open-access scholarship goes through the same type of peer review that traditional scholarship does. Originally a fringe movement, open access has gained credibility over time, with support from major publishing houses that include Cambridge University Press, Elsevier, and Wiley, which all offer authors the opportunity to publish open access (Björk 2011; Laakso et al. 2011). Some US government organizations, such as the National Institutes of Health, require that funded research be made publicly available through some form of open access (NIH 2021). By now, open-access advocates have formed a full-fledged movement that promotes these initiatives with what some commentators describe as evangelical zeal (Anderson and Squires 2017). In this vision, open-access publication is the harbinger of a new frontier in global communication and the accessibility of knowledge (Suber 2012, 1–4).

Yet, few studies have measured the impact of open-access scholarship on any specific field and its progress toward the dream of a global discourse.2Sabharwal et al. 2014 is one of the few studies to attempt this in any field. To answer this question, this article presents a comprehensive survey of trends in open-access music scholarship by examining 189 existing open-access music journals. A number of these journals openly advertise their founders’ global aspirations, usually through a variation of the following statement: “This journal provides immediate open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge” (Carl Nielsen Studies [The Royal Danish Society 2003–20], DEBATES [Centro de letras 1997–], Musicological Annual [The Department of Musicology at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana 1965–] and others).

Although open-access music journals have made a great deal of research available to a global audience, the journals themselves reflect economic and cultural power imbalances in global academic culture across the globe. They are, in fact, largely dominated by Western perspectives, as is most scholarship across all disciplines (Chan and Gray 2013, 202). This article outlines the situation in detail, and closes with recommendations about how open-access music journals might help realize their potential for global discourse.

Barriers to the Creation of Global Discourse

Traditional models of sharing research, such as subscription-based journals, have struggled to create global dialogue, as economic issues prevent readers from accessing the full range of relevant research. The rapidly rising cost of subscriptions has made it difficult for libraries to afford a full range of such research, and individuals often cannot afford to subscribe to journals not carried by their libraries (Suber 2012, 29–30). This issue is particularly pressing for libraries in developing or previously colonized countries, whose acquisitions budgets are small compared to those in industrialized nations (Mboa Nkoudou 2016; Balaram 2013, 403; Willinsky 2005, ix–x; Suber 2012, 30, 32). Researchers whose libraries do not provide access to needed resources face a significant handicap, having to rely on interlibrary loan services or networking with colleagues at better-funded institutions.

While open-access journals remove access barriers for readers, they come with a new set of barriers that affect researchers and sponsoring organizations. Traditional publishing relies on subscribers to pay the cost of publication (and often, to generate a profit); open access transfers the cost over to the author or (more commonly) to a sponsor such as a university department or an academic society. Site maintenance, formatting, web-hosting, and digital archiving services are rarely free, even if the editors and reviewers are volunteers. As open-access scholar John Willinsky puts it, “The open access article cannot be read without a substantial investment in hardware, software, and networking” (2005, xii). If the traditional journal publishing model asks, “Who can afford to access this research?,” the open-access publishing model ultimately asks, “Who can afford to reach a larger audience?” Therefore, traditional publishing can make sense for underfunded academic societies that cannot afford to invest in the services, hardware, and software necessary to support open-access initiatives. Furthermore, the transition from traditional to open-access publishing would pose significant barriers for the staff of a journal without such resources.

Open-access journals (like some subscription journals) sometimes ask authors to pay publication fees (“article processing charges”); these fees can be exorbitant—up to $5000 per article (Socha 2017). It should come as no surprise that publication fees are prevalent among journals that are run by commercial publishing houses (Socha 2017), and that these fees are particularly unaffordable for non-Western scholars (Iyer and Azhar 2013). Such fees are also common among the predatory journals that exercise little quality control and promise rapid publication (Berger and Cirasella 2015, 132). However, broad studies of academic journal publishing have demonstrated that most open-access journals do not charge publication fees at all, especially in the arts and humanities (Kozak and Hartley 2013, 2593–94; Berger and Cirasella 2015, 134; Suber 2012, 142).

Regardless of whether one publishes in a traditional or open-access journal, another type of access barrier concerns the free exchange of ideas across cultures. Scholars from developing countries often face pressure from their governments or university administrations to publish in internationally renowned journals, especially in English (Engelson 2018, 164, 168). These expectations, as C. K. Raju (2010, 1) has argued, can lead to lasting academic inequality: “a scientific innovation is not treated as credible until it has been endorsed by the West (e.g., published in a “prestigious” [meaning Western] journal); this practice ensures that the non-West can never out-innovate or catch up with the West in science. . . .” Similarly, Chan and Gray (2013, 203, 209) have shown that scholars from outside the West often try to satisfy Western research expectations, rather than producing work that is directly relevant to their own communities. This imbalance between Western and non-Western perspectives in global scholarship can lead to the false impression that non-Western scholars are not producing innovative or high-quality research, especially if one relies on citation statistics and journal impact factors (Chan and Gray 2013, 205; Raju 2010, 6; Jeater 2018, 9–11).

Methodology: Analyzing the List of Open-Access Music Journals

Most of the data used in this article comes from the List of Open-Access Music Journals (LOAMJ), a database that I built from 2019–20 to survey existing OA music journals (Franke 2020b). Currently, the LOAMJ contains information about 189 journals in 28 languages; 142 of these journals are currently accepting submissions, and 47 are inactive, but have kept their archives online. Further data on publication fees for 38 partially open-access journals from major commercial publishers are available in a second database (Franke 2020a).

The LOAMJ is a comprehensive list of “gold” open-access journals (meaning that all articles in each journal are freely available to readers). It covers all areas of music research (including musicology, ethnomusicology, music theory and analysis, music education, music business, music therapy, music librarianship, performance studies). Journals that charge publication fees are included in the list, and these fees are documented. However, no hybrid open-access journals (more on these below) are included, as these do not consistently make their contents available for free. Similarly, journals that focus on the arts in general (such as theatre and dance, as well as music) are not included, as these do not consistently focus on music. Consequently, the LOAMJ does not include all journals that publish open-access scholarship on music, but it does include all exclusively open-access journals that consistently publish research on music.

As predatory open-access journals are a well-publicized problem, it is worth discussing the LOAMJ in this context. Two common strategies have emerged for dealing with predatory journals: (1) to publicly name suspicious journals or publishers via a blacklist, such as Beall’s List (Beall 2021) or one of its successors (Stop Predatory Journals 2017); (2) to list certifiably reliable journals or publishers via a whitelist, such as the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ 2020) or the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA 2008–21) (Berger and Cirasella 2015, 132–34). The LOAMJ is a gray list, which does not endorse or condemn any journal, but contains sufficient information for readers to evaluate the relevance and credibility of each journal for themselves. As almost all the journals on the list are included in reputable databases, such as RILM (Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale 1966–2021), DOAJ,

KOAJ (National Research Foundation of Korea 2013), J-STAGE (Japan Science and Technology Agency 2002–), and ERIH Plus (Norwegian Centre for Research Data2021),

and hardly any seem to charge publication fees, few journals on the LOAMJ are likely to be predatory.

The core of this article is an analysis of the LOAMJ, which provides basic data on the journals’ disciplinary focus, language(s) of publication, geographic origin, relationship to academic societies, publishing platform, publication frequency, licensing information, peer review processes, and editorial board information. From this data, it is possible to objectively describe the prevalence of English as a language, the significance of journals devoted to translated scholarship, and the global dominance of Western disciplinary perspectives, as well as other issues.

Results: The State of Open-Access Music Research

Publication fees

As of July 2021, only 7 of the 189 journals in the LOAMJ state on their websites that they charge publication fees; another 59 openly state that they do not charge publication fees; while the remaining journal sites do not discuss publication fees at all. When the 47 inactive journals are removed from consideration, then the proportion of journal sites that discuss publication fees rises, as does the proportion of journals which openly state that they do not charge fees (see Table 1). Finally, 40 journals are published with free Open Journal Systems software developed by the Public Knowledge Project, which presumably reduces some of the maintenance costs of each journal (only one music journal that uses Open Journal Systems software openly states that it charges publication fees—Проблемы музыкальной науки (Music Scholarship). Although some journals may have publication fees that are not advertised on their websites, it is likely that most of the LOAMJ journals do not charge fees, given their high rate of sponsorship by research societies and universities.

Table 1. Publication fees in LOAMJ journals as of July 2021

|

Don’t discuss publication fees |

Discuss publication fees |

Charge fees |

Don’t charge fees |

|

|

Total (189) |

121 (64%) |

68 (36%) |

9 (5%) |

59 (31%) |

|

Active journals (142) |

80(56%) |

62 (44%) |

8 ( 5.6%) |

54 (38%) |

In contrast, one can find higher (and more visible) publication fees from music journals printed by major publishers, such as the official journals of the Society for American Music, the Royal Music Association, and the Society for Music Theory. There, journals are almost all “hybrid” OA, meaning that the journal as a whole is still marketed via subscriptions, but individual authors can choose to publish their work open-access if they pay a fee (see Björk 2017; Suber 2012, 140). Some publishers also waive or discount OA publication fees for authors from developing countries. In general, however, publication fees average around $3000 per article if one wants to publish an open-access music article in a hybrid journal, a figure that is in line with global publishing norms (Franke 2020a; Björk 2017, 6). This is in stark contrast to the publication fees charged by the journals in the LOAMJ, which reach a maximum of 1180 GBP, and which are generally below $500.

Consequently, relatively few authors actually publish open-access articles in hybrid journals (Suber 2012, 141; Björk 2017, 6). A survey of hybrid music journals from 2015 to 2019 reveals several that have not published a single open-access research article in that time (for instance, the Journal of Musicological Research, Music Theory Spectrum, or the Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa). In the same period, the Musical Quarterly published one open-access article, whereas the Cambridge Opera Journal published two. No journal surveyed had made more than 18% of its articles freely available.3Of the journals surveyed (which also included Popular Music and Society and Early Music), the Journal of the Society for American Music had the highest ratio of freely available articles, with 14 of 79 articles published since 2015. These facts suggest that hybrid OA is an ineffective method for reaching a larger audience.

Sponsorship

As shown above, relatively few gold open-access music journals have publication fees; official sponsorship by academic organizations must be a factor in this, although detailed financial information regarding the support of open-access journals is not readily available. A survey of the LOAMJ, conducted in July 2021, reveals that 172 of 189 journals (91%) have some kind of official sponsorship. The most significant sponsors are universities and conservatories (89 journals or 47% of the total) and academic societies (65 journals or 34% of the total). Independent research centers are also a significant source of sponsorship (19 journals or 10% of the total): examples include the Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw and the L’École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris. Some journals are sponsored simultaneously by multiple organizations, such as an academic society working in tandem with a university.

Sponsorship patterns reveal differing attitudes toward open access across the globe. Almost all open-access music journals in Japan and South Korea are sponsored by academic societies. The same is true for less than a third of journals from the United States and for none from the United Kingdom. Instead, the bulk of open-access music journals in the US (59%) and the UK (70%) are produced by universities (which are also major journal sponsors in Spain, Italy, and Brazil). Canadian journals reverse this ratio, with 55% being sponsored by academic societies and 33% by universities. French and German open-access music journals, on the other hand, are relatively independent of universities, being more likely to be sponsored by an independent research center (66% of French journals) or by an academic society (60% of German journals).

The specific costs of sponsoring an open-access journal are rarely made public. However, one of the few studies to address this topic demonstrates that it is possible to run a journal using volunteer staff and open-source software (such as Open Journal Systems [Public Knowledge Project—Simon Frazier University Library 2014]) on a minimal budget. Yet, even in this case, both creators of the journal in question were employed by Canadian public universities, and acknowledge the support of their institutions not only in the founding of the journal through “a number of grants” but also in the purchase of both necessary software and a domain name (Willinsky and Mendis 2007). The founding and maintenance of a journal might therefore be a minimal expense for a wealthy institution, but these costs might be prohibitive for societies without the existing hardware and software.

Geography and Power

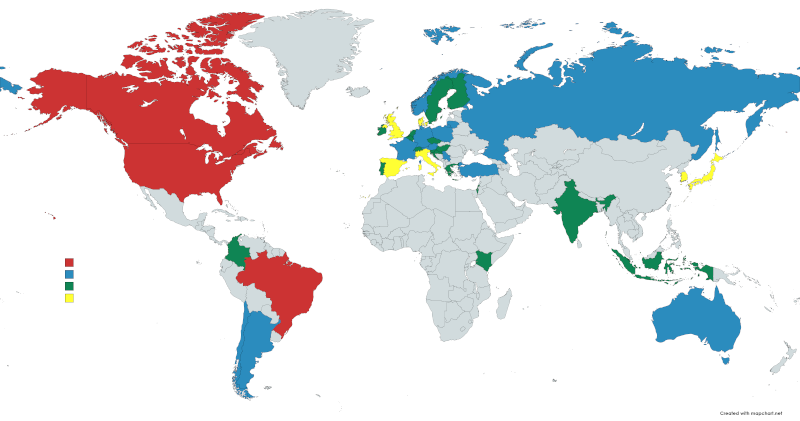

Most open-access music journals are based in the Americas, Western Europe, or industrialized nations that have good access to the internet and a highly developed educational infrastructure. A geographic analysis of the LOAMJ shows that open-access music journals are primarily produced in Western countries (see Figure 1). This data for music matches that for academic production in general (Flick 2011, 14–15). The causes for this situation are difficult to pin down, but are probably linked to economic, historic, and cultural factors.

Figure 1: The global distribution of open-access music journals in the LOAMJ as of July 2021, created using mapchart.net software, freely available under a Creative Commons CC BY SA 4.0 license). Green countries have published 1–2 journals; Blue, 3–5, Yellow, 6–10; Red, 11 or more.

Raw economic power might play a role in this situation in that the world’s wealthiest economies produce an inordinate percentage of the LOAMJ. The G8 countries (France, Germany, Italy, UK, US, Russia, Japan, and Canada) have produced 45% of the journals in the LOAMJ (86 out of 189). The United States alone has produced 19% of the LOAMJ (36 journals). Yet, if there were a correlation between economic power and the production of open-access journals, India (two journals) and China (one journal), two of the world’s largest economies, should be far better represented in the LOAMJ.

Internet usage provides a more nuanced way of understanding the link between economic power and the availability of open-access music research (see Table 2). Thus, North America4“North America” here refers to the continent as a whole—including Canada, the United States, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. However, as of July 2021, all open-access music journals from the continent originate in either the United States or Canada. The exclusion of other North American countries from this discussion is only for want of data. produces 25% of all open-access music journals, creating them at a ratio five times greater than its share of the global population. This corresponds to the highest rate of internet usage in the world. Similar data can be found for Europe and Australia, which have produced journals at high rates. Yet the dearth of journals from Asia and Africa demonstrates that this correlation does not consistently hold true: otherwise, both continents might reasonably be expected to produce more journals. Part of the problem is that the available data on internet usage do not specify the quality of the internet connection available—bandwidth, speed, and reliability are not taken into account. As Piron (2018) has noted, her African and Haitian colleagues regularly ask, “How [can we] benefit from [open access] while our access to the web, computer and even electricity is not guaranteed?”

Table 2. A continent-by-continent breakdown of open-access music journals compared to world population, July 2021 (world population data from Internet World Stats [2020])

|

Number of journals |

Percentage of the total |

Percentage of global population (2020) |

Internet usage, in percentage of population |

Ratio of journals to world population |

|

|

Europe (including Russia) |

77 |

40.7% |

10.7% |

87.2% |

4:1 |

|

North America |

48 |

25.4% |

4.7% |

90.3% |

5:1 |

|

Asia (excluding Russia) |

25 |

13.2% |

58.4% |

58.5% |

0.23:1 |

|

South America |

18 |

9.5% |

8.4% |

71.5% |

1.1:1 |

|

Australia/Oceana |

5 |

2.6% |

0.5% |

67.7% |

5:1 |

|

Africa |

1 |

0.5% |

17.2% |

42.2% |

0.03:1 |

|

Unclear/multinational |

15 |

7.9% |

One last variable might explain part of the seemingly anomalous results for Asia and Africa mentioned above, that is, the correlation between freedom of information and the different rates of journal production. Varying levels of political freedom and internet censorship are common around the world, and consequently, it would be a mistake to believe that the internet is “an inherently emancipatory tool” (Warf 2011, 2). The Freedom House ratings, which evaluate the transparency and fairness of governments across the world, have tracked repressive regimes in both China and in central Africa, which might partly explain the relative lack of journals from these regions (Freedom House 2020). Similarly, Freedom House has begun to track “Internet Freedom” in select countries across the globe, and their findings similarly seem to show that internet censorship is common in countries with repressive governments. Unsurprisingly, there seems to be a correlation between government censorship of the internet and low production of open-access journals. The disparity between economic power, population, internet access, and scholarly production is therefore part of a much bigger picture.

Finally, varying attitudes toward open access persist across the world, indicating different levels of willingness to use it. Some European countries that were “Great Powers” at the turn of the twentieth century, such as Spain, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Turkey, and Russia, have been relatively slow to publish open-access music journals, probably because existing academic networks in these countries have traditionally relied on printed media. Instead, open-access music journals have been regularly produced by European countries that have not wielded great political or economic power for the last hundred years. Denmark, Serbia, Ireland, Lithuania, Croatia, Portugal, Sweden, and Greece have all produced far more journals per capita than the historically powerful states. Such journals seem to be designed to reach global audiences (especially as many journals accept and publish articles in multiple languages). Were they to attempt to market their journals online via subscription or fee, it is possible that this policy might alienate foreign readers. For academic societies in these countries, open access is presumably an attractive way to amplify their message. Some of these journals are directly supported by government agencies, such as the Croatian Ministry of Culture, the Royal Danish Library, or the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Asian countries, such as South Korea and Japan, which have joined the Western, globalized economy and have reliable internet access, have also produced a number of open-access music journals. However, as will be discussed below, the focus and global reach of these journals is intentionally limited. On the other hand, there seem to be no open-access music journals solely originating from China; most Chinese journals are only available outside China through the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure database (CNKI 1996–), which is available by subscription only. The only journal in LOAMJ with any affiliation with China is CHIME: Journal of the European Foundation for Chinese Music Research, which is partly sponsored by the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, and partly by the CHIME foundation based in Leiden, the Netherlands (1990–).

Unsurprisingly, open-access journals are far less likely to exist in developing countries or in countries that have only recently gained independence from colonial rule; these countries appear to rely on traditional print media for their music journals. For example, there appears to be only one open-access music journal from the entire continent of Africa—African Musicology Online based in Kenya (Bureau for the Development of African Musicology 2016). Other music journals from the continent, such as the Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa (South African College of Music 2004–), SAMUS: South African Music Studies (South African Society for Research in Music 2006–), or the Journal of the Association of Nigerian Musicologists (Association of Nigerian Musicologists 2009–10), are available by subscription only.

Strikingly, there seems to be one truly open-access music journal in India—Sangeet Galaxy (Sangeet Galaxy Foundation 2012–), a bilingual Hindi and English publication. This finding is particularly unusual as many Indian journals in other fields are open access (Misra and Agrawal 2019, 4–5). Further research, perhaps by someone with a functional knowledge of Hindi or other Indian languages, is needed to understand this anomalous result.

Language and access

Just as a plurality of open-access music journals are based in the US, so too is English the single most popular language (see Table 3). Of the 189 entries in the LOAMJ as of July 2021, 79 are published exclusively in English, and 28 are published exclusively in another language (Korean, Japanese, and Spanish are the most common). Another 82 journals are published in more than one language; English is almost always one of the options, although many journals that accept English submissions mainly publish in other languages. There are also journals from outside the Anglophone world that only publish in English, such as Jurnal Seni Musik (from Indonesia), Mousikos Logos (from Greece), Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy (from Norway), and MusMat (from Brazil). The use of English as the default language of scholarship has been described as a type of intellectual imperialism by researchers such as Amber Engelson (2018, 164), although the use of English seems to be a conscious choice by scholars around the world. These figures match the available data for the dominance of English in research as a whole (Flick 2011, 16–17).

Table 3. The dominance of English in open-access music journals

|

Total |

Journals that accept English submissions |

|

|

1 language |

107 |

79 (74%) |

|

2 languages |

41 |

40 (98%) |

|

3 or more languages |

41 |

40 (98%) |

|

Total |

189 |

159 (84%) |

Multilingual music journals help to create scholarly communities that are connected by language and geography. The most common linguistic pattern is the use of a local language plus English. It seems likely that the editors of these journals are seeking an international audience through their use of English; this is especially true for journals from countries such as Norway, Israel, Poland, and Greece, whose languages are not widely spoken on a global level.

The official languages often reflect existing lines of linguistic and cultural connection. Instead of creating truly global dialogues, then, multilingual journals often reinforce local connections between scholars from neighboring countries. Spanish/Portuguese/English is a popular combination throughout Iberia and South America, whereas Swedish/Danish/Norwegian/ German/English is common throughout Scandinavia. Multilingual journals from central Europe typically feature a combination of German, French, or Italian, in addition to local languages.

If European journals tend to include other languages as a way of reaching international audiences, many East Asian journals are geared toward local audiences. Many of these journals cover local and traditional musics, or focus on specific issues relevant to their host societies. From 2012 to 2018, Sangeet Galaxy published 54 of 124 (44%) research articles in English. However, these articles are almost entirely focused on Indian topics, and the use of English probably reflects its role as a lingua franca in India, instead of an attempt to reach readers outside of India. Similarly, the only Korean open-access music journal to include a foreign language is 인간행동과 음악연구 (Journal of Music and Human Behavior), which accepts publications in Korean and English (Korean Music Therapy Education Association 2005–). However, as of July 2021, it had not published an English article since 2017; from 2015 to 2020, it had only published three articles (out of 59) in English. Only one journal seems to be aiming for a global audience: 音楽学 (Ongakugaku, the Journal of the Musicological Society of Japan), which routinely publishes articles in Japanese, but which includes abstracts in English, French, or German (Musicological Society of Japan 2011–).

This discussion of language in open-access music journals would not be complete without considering the role of translation. Open-access music journals devoted to translations have only begun to emerge in the last six years, logically originating in ethnomusicology, a discipline that has long sought to create dialogue between musical cultures. The two chief examples, Ethnomusicology Translations (Society for Ethnomusicology 2015–) and Translingual Discourse in Ethnomusicology (University of Vienna 2015–), were both founded in 2015. Each publishes English translations of scholarship from around the world. The existence of these journals suggests both the need for native English speakers to interact with scholarship from around the world, and the normative status of English as a language of scholarly inquiry. It is striking (if unsurprising) that, to date, there are no comparable music journals that publish translations from English into Spanish or other globally popular languages.

Disciplinary boundaries

Many open-access music journals easily fall into the common disciplines associated with music study in the West: the journals’ websites frequently describe their affiliation with such disciplines as musicology, ethnomusicology, music theory, and music education. The disciplinary tags in the LOAMJ, as noted above, are partly based on these self-descriptions, although some of the tags are editorial, based upon my impression of their content.5In most cases, the information on the LOAMJ was taken from each journal’s website, although some correspondence with journal editors has addressed questions whose answers could not be found online. Journal keywords are based on the journal’s description on its webpage and on a survey of the journal’s contents; uniform terminology has been used throughout the database to make results more accessible to readers. (“Music theory” and “music analysis,” for example, are both categorized as “theory” in the LOAMJ; “musicology” and “music history” are similarly conflated). The author’s limited skills in Korean, Indonesian, and Japanese have also influenced the data-gathering process for journals in these languages. In general, the disciplinary tags reveal that music history (116 tags) dominates the LOAMJ, followed by music theory (53 tags), ethnomusicology (47), music education (39), popular music (26), and performance studies (27).

The dominance of Western disciplines is no surprise among the vast body of journals based in Europe or North America, locations in which Western traditions have roots and historical associations. But they are also observable even in East Asian journals, some of which have clearly imported Western disciplinary boundaries and expectations. For example, 서양음악학 (the Journal of the Musicological Society of Korea) exclusively focuses on Western music (Musicological Society of Korea 2002–); Korean topics are addressed in 음악과 문화 (Music and Culture) (Korean Society for World Music 1999–). Meanwhile, 音楽学 (Ongakugaku: Journal of the Musicological Society of Japan), focuses on Western music but includes articles on Japanese composers who have drawn on Western traditions, such as Toru Takemitsu and Toshiro Mayuzumi.

A number of open-access journals, however, have begun to collapse disciplinary boundaries in new and surprising ways. About thirty-nine journals on the list are open to submissions from three or more research areas, meaning that they are more likely to accept articles that cross disciplinary boundaries, and their contents are eclectic and not limited by a single repertoire or genre of music. For example, a single issue (vol. 4, no. 2) of the Revue musicale OICRM contains articles on French music criticism, the music of Astor Piazzolla, and rock opera (L’Observatoire interdisciplinaire de création et de recherche en musique 2012–), while successive issues of the Revista musical chilena cover topics as divergent as jazz in Cuba, Chilean children’s songs, the music of Alberto Ginastera, and the survival of Gregorian chant in Chile (Universidad de Chile, 1945–). Such journals often serve local communities and are an outlet for all forms of music scholarship in a region—journals such as the Revista Brasileira de Música (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro 2010–), Danish Musicology Online (Danish Research Council for Independent Research 2010–), or the Journal of the Society for Musicology in Ireland (Aontas Ceoleolaíochta na hÉireann 2005–) fulfill this function in some way.

Finally, a number of open-access music journals are creating unique, specific focuses that have been overlooked or marginalized in the traditional study of music. These include music and gender studies (Kapralova Society Journal and Gender, Education, Music, Society), performance practice (Performance Practice Review), computerized and robotic music (Journal of Creative Music Systems), connections between music and dance (Accelerando [Belgrade Center for Music and Dance 2016–]), musical theatre (Act: Zeitschrift für Musik & Performance [Forschungsinstitut für Musiktheater in Thurnau 2010–]), film and videogame music (Mediamusic/Медиамузыка [Mediamusic 2012–]), and scientific approaches to musical cognition and acoustics (Music & Science). It thus seems that open access is useful for the development of new scholarly approaches and methodologies.

Conclusions

There are several promising directions for future studies of the material discussed in this article. One might consider the topics and disciplinary alignment of the articles in these journals and compare them to traditional subscription journals. Similarly, one could study authorial affiliations to determine whether or not there was anything approaching a balanced discourse in which authors from different parts of the world were evenly represented. Finally, the development of alternatives to open-access journals, such as open-access article repositories (“green” open access), is completely unexplored in music research, and deserves careful attention (as of July 2021, there are currently only ten music repositories listed in the Directory of Open Access Repositories (OpenDOAR 2005–).

This study’s data, however, point strongly toward several issues affecting open-access music journals. I raise these issues while bearing in mind the many benefits that open-access music journals already offer. Extensive scholarship has documented a correlation between open-access publication and higher rates of citation (Jhangiani 2017, 269; Suber 2012, 15, 40; Lewis 2018; Millet-Reyes and Bailey 2008). Open-access music journals have offered improved access for readers across the world, and have helped strengthen local communities and discourse. At the same time, the following matters deserve attention if open-access journals are to realize the possibility of a truly global musical discourse.

1. The chief access barrier in open-access music scholarship—which society, university, or research group can afford to support an open-access journal—has had a critical effect on the development of global discourse in scholarship. Certainly, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that making a journal fully open access is effective at increasing its global profile. However, its sponsors’ ability to do this depends on whether they can afford to support the costs, provide the necessary hardware and software, and have access to reliable internet service (government censorship might also play a role). Therefore, not all organizations can afford to spread their message at the same rate, leading to unequal representation in global discourse.

2. Open-access journals have amplified the perspectives of scholars and academic societies in industrialized states, especially the United States and the European Union. As these regions already wield tremendous political, economic, and cultural power, open-access technology has provided a tool by which Western perspectives can spread even more effectively across the globe (Piron 2018). Although the existing model has provided a global audience for this local discourse, it runs the risk of creating an echo chamber in which Western disciplinary approaches, perspectives, and topics are the main ones that matter.

3. Authors based in developing countries, especially those that were historically colonized by European powers, might sometimes enjoy the benefit of discounted publication fees in hybrid open-access journals run by major Western publishers. However, their own local journals are mostly available on a subscription basis, meaning that their research is less likely to reach audiences in industrialized countries. Consequently, even though there is global access to research about music, global dialogue does not necessarily follow. Music research published in the United States is more likely to be freely available than music research published in Nigeria.

4. The dominance of Western disciplinary models and of English as a preferred language of scholarship (musical or otherwise) reinforces the current status quo (Mboa Nkoudou 2016; Jeater 2018, 9). The overwhelming reliance on Western disciplinary models reflects the assumption that these are inherently the best models and that scholars in other parts of the world must adapt to them to create real knowledge worthy of sharing (Piron 2018). This approach overlooks the unique contributions of scholars who do not operate within traditional Western disciplines (Chilisa 2017; Piron 2018; Raju 2010, 10–11). The regular use of a single language for scholarship in general has produced a culture in which some scholars cannot participate fully (Engelson 2018, 163–64, 168).

These issues do not all have ready solutions—particularly the first and third ones. Some of these issues cannot be addressed adequately by individual journals, but instead require attention by scholarly societies. Nonetheless, making existing journals more inclusive might help address part of the problem. Therefore, the rest of this essay offers suggestions that might help spark discussion among those who want to use their journals to stimulate global dialogue about music.

1. A monolingual journal could accept publications in more languages. Given that Spanish is the dominant language of Latin America, and French is an official language in Canada, publishing in either of these languages might be an option for broadening the scope of North American journals.

2. As a supplement or alternative to the first option, journals could regularly publish translations of scholarship in other languages. This would allow local readers to continue reading in their own language while still interacting with scholarship from other cultures and perspectives. At the same time, professional translations will probably come with significant expenses, especially for non-profit academic societies and journals.

3. Journals could involve more international scholars in their editorial boards to broaden the range of perspectives involved in reviewing research (this point echoes Raju 2010, 6–7). This is particularly relevant for music disciplines that are shaped by the researcher’s background and experiences as well as by data, and which are consequently most likely to be shaped by the cultural perspectives of its editorial board.

4. Journals could run special, invited issues on relevant topics, as seen through other cultural perspectives (perhaps in translation). These new perspectives might not only raise their readers’ global awareness but also make the journal more interesting to readers in other countries. These special issues could supplement the journal’s typical run so that local authors would not be sidelined by this approach. For example, a US journal could commission an issue containing articles (and pay for their translation into English, if necessary) from leading researchers in countries such as Japan, Brazil, India, or South Africa. These special issues should be led by guest editors from the countries involved, so that these publications truly represent the priorities and interests of researchers from those regions.

These suggestions, fragmented as they are, can only serve as conversation starters, not as prescriptive calls for change. Ultimately, although open-access music journals provide access to scholarship, they have not yet developed their potential to bring about global dialogue. Consequently, their editors should consider the type of global discourse to which they are contributing, be conscious of their ability to alter it, and consider practical steps that will allow their journals to realize their global potential.

Notes

1. This article was written with the support of a Junior Faculty Writing and Creative Works Summer Academy fellowship at Howard University in the summer of 2020. I offer my sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers of this journal and to my mentors and colleagues who gave me feedback on this work.

2. Sabharwal et al. 2014 is one of the few studies to attempt this in any field.

3. Of the journals surveyed (which also included Popular Music and Society and Early Music), the Journal of the Society for American Music had the highest ratio of freely available articles, with 14 of 79 articles published since 2015.

4. “North America” here refers to the continent as a whole—including Canada, the United States, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. However, as of July 2021, all open-access music journals from the continent originate in either the United States or Canada. The exclusion of other North American countries from this discussion is only for want of data.

5. In most cases, the information on the LOAMJ was taken from each journal’s website, although some correspondence with journal editors has addressed questions whose answers could not be found online. Journal keywords are based on the journal’s description on its webpage and on a survey of the journal’s contents; uniform terminology has been used throughout the database to make results more accessible to readers. (“Music theory” and “music analysis,” for example, are both categorized as “theory” in the LOAMJ; “musicology” and “music history” are similarly conflated). The author’s limited skills in Korean, Indonesian, and Japanese have also influenced the data-gathering process for journals in these languages.

References

Aontas Ceoleolaíochta na hÉireann (Society for Musicology in Ireland). 2005–. Journal of the Society for Musicology in Ireland. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://www.musicologyireland.com/jsmi/index.php/journal.

Anderson, Talea, and David Squires. 2017. “Open Access and the Theological Imagination.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 11, no. 4 (Fall).

Association of Nigerian Musicologists. 2009–2010. Journal of the Association of Nigerian Musicologists. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/janm/index.

Balaram, Padmanabhan. 2013. “Open Access: Tearing Down Barriers.” Current Science 104, no. 4 (February 25): 403–4.

Beall, Jeffrey. 2021. Beall’s List of Potential Predatory Journals and Publishers. Last updated March 7, 2021. https://beallslist.net/.

Belgrade Center for Music and Dance. 2016–. Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://accelerandobjmd.weebly.com/.

Berger, Monica, and Jill Cirasella. 2015. “Beyond Beall’s List: Better Understanding Predatory Publishers.” College & Research Libraries News 76, no. 3 (March): 132–35.

Björk, Bo-Christer. 2011. “A Study of Innovative Features in Scholarly Open Access Journals.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 13 no. 4. https://www.jmir.org/2011/4/e115/.

Björk, Bo-Christer. 2017. “Growth of Hybrid Open Access, 2009–2016.” PeerJ 5 5.

Bureau for the Development of African Musicology (BDAM). 2016. African Musicology Online.Accessed April 20, 2021. https://africanmusicology.online/.

Centro de letras e artes/Unirio. 2020. DEBATES: Cadernos do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música. Accessed April 20, 2021. http://www.seer.unirio.br/index.php/revistadebates/about.

Chan, Leslie, and Eve Gray. 2013. “Centering the Knowledge Peripheries through Open Access: Implications for Future Research and Discourse on Knowledge for Development.” In Open Development: Networked Innovations in International Development, edited by Matthew L. Smith and Katherine M. A. Reilly, 197–222. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chilisa, Bagele. 2017. “Decolonising Transdisciplinary Research Approaches: An African Perspective for Enhancing Knowledge Integration in Sustainability Science.” Sustainability Science 12: 813–27.

Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure database (CNKI). 1996–. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://oversea.cnki.net/index/.

Danish Research Council for Independent Research. 2010–. Danish Musicology Online / Dansk Musikforskning Online. Accessed May 9, 2021. http://www.danishmusicologyonline.dk.

The Department of Musicology at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana. (1965–). Musicological Annual. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://revije.ff.uni-lj.si/MuzikoloskiZbornik/about.

The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). 2020. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://doaj.org/.

Directory of Open Access Repositories. 2005–. OpenDOAR. Accessed May 9, 2021.https://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/opendoar/.

Engelson, Amber. 2018. “‘Resources are Power’: Writing across the Global Information Divide.” In Thinking Globally, Composing Locally: Rethinking Online Writing in the Age of the Global Internet, edited by Rich Rice and Kirk St. Amant, 161–81. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Flick, Corrine M. 2011. “Geographies of the World’s Knowledge.” Convoco Foundation and the Oxford Internet Institute. Accessed July 26, 2021. https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/archive/downloads/publications/convoco_geographies_en.pdf

Forschungsinstitut für Musiktheater in Thurnau. 2010–. Act: Zeitschrift für Musik & Performance. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://www.act.uni-bayreuth.de/de/index.html.

Franke, Matthew. 2020a. “Article Processing Charges for Hybrid OA (music) Journals.” Updated June 19, 2020. https://www.obvibase.com/p/JVdTdTmbyGxYPZdU.

———. 2020b. “List of Open-Access Music Journals.” Updated July 26, 2021. https://www.obvibase.com/p/vctf3wpg7FKABHnx.

Freedom House. 2020. “Explore the Map: Global Freedom Status; Internet Freedom; Democracy Status.” Accessed August 14, 2020. https://freedomhouse.org/explore-the-map?type=fiw&year=2020.

Internet World Stats. 2020. “World Internet Usage and Population Statistics. 2020 Year-Q2 Estimates.” Page last updated 20 July 2020; accessed August 14, 2020. https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

Iyer, Veena, and Gulrez Shah Azhar. 2013. “Open Access or No Access.” Current Science 105, no. 9 (November 10): 1202.

Japan Science and Technology Agency. 2002–. J-STAGE. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/.

Jardine, Elizabeth, Maureen Garvey, and J. Silvia Cho. 2017. “Open Access and Global Inclusion: A Look at Cuba.” CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/si_pubs/78/.

Jeater, Diana. 2018. “Academic Standards or Academic Imperialism? Zimbabwean Perceptions of Hegemonic Power in the Global Construction of Knowledge.” African Studies Review 61, no. 2 (July): 8–27.

Jhangiani, Rajiv. 2017. “Open as Default: The Future of Education and Scholarship.” In Open: The Philosophy and Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and Science, edited by Rajiv Jhangiani and Robert Biswas-Diener, 268–79. London: Ubiquity Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.v.

Kajikawa, Loren. 2019. “The Possessive Investment in Classical Music: Confronting Legacies of White Supremacy in U.S. Schools and Departments of Music.” In Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindness across the Disciplines, edited by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Luke Charles Harris, Daniel Martinez HoSang, and George Lipsitz, 155–74. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Korean Music Therapy Education Association. 2005–.인간행동과 음악연구 (Journal of Music and Human Behavior). Accessed May 9, 2021. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/landing/journalVolumeList.kci?sere_id=SER000001994.

Korean Society for World Music.1999–.음악과 문화 (Music and Culture). Accessed May 9, 2021. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/landing/journalVolumeList.kci?sere_id=000888.

Kozak, Marcin, and James Hartley. 2013. “Publication Fees for Open Access Journals: Different Disciplines—Different Methods.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 64, no. 12 (December): 2591–94.

Laakso, Mikael, Patrik Welling, Helena Bukvova, Linus Nyman, Bo-Christer Björk, and Turid Hedlund. 2011. “The Development of Open Access Journal Publishing from 1993 to 2009.” PLoS ONE 6 no. 6, e20961. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0020961.

Lewis, Colby. 2018. “The Open Access Citation Advantage: Does It Exist and What Does It Mean for Libraries?” Information Technology and Libraries 37, no. 3 (September): 50–65.

Maus, Fred Everett. 2004. “Ethnomusicology, Music Curricula, and the Centrality of Classical Music.” College Music Symposium 44. https://symposium.music.org/index.php/44/item/2213-ethnomusicology-music-curricula-and-the-centrality-of-classical-music.

Mboa Nkoudou, Thomas Hervé. 2016. “Le Web et la production scientifique africaine : visibilité réelle ou inhibée?” http://www.projetsoha.org/?p=1357.

Mediamusic [Медиамузыка]. 2012 –. Accessed May 9, 2021. http://mediamusic-journal.com/.

Millet-Reyes, Benedicte, and Barrie A. Bailey. 2008. “Internet Access, Journal Ranking, and Citation Performance.” Journal of Financial Education 34 (Fall): 28–39.

Misra, Durga Prasanna, and Vikas Agarwal. 2019. “Open Access Publishing in India: Coverage, Relevance, and Future Perspectives.” Journal of Korean Medical Science 34 no. 27 (July 15): e180.

Musicological Society of Japan. 2011–. Ongakugaku: Journal of the Musicological Society 音楽学. Accessed May 9, 2021. http://www.musicology-japan.org/english.html#Ongakugaku.

Musicological Society of Korea. 2002–.서양음악학, Journal of the Musicological Society of Korea. Accessed May 9, 2021. http://www.musicology.or.kr/ and https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/landing/journalVolumeList.kci?sere_id=001386.

National Institutes of Health. “Public Access Policy.” Accessed May 9, 2021. https://publicaccess.nih.gov/policy.htm.

National Research Foundation of Korea. 2013. “Korean Open Access Journals” (KOAJ). Accessed April 15, 2020. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/landing/index.kci.

Norwegian Centre for Research Data. 2021. “ERIH Plus (European Reference Index for the Humanities and Social Sciences).” Accessed April 15, 2021. https://dbh.nsd.uib.no/publiseringskanaler/erihplus/.

L’Observatoire interdisciplinaire de création et de recherche en musique. 2012–. Revue musicale OICRM. Accessed May 9, 2021. http://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/.

The Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association (OASPA). 2008–. Accessed April 15, 2021 https://oaspa.org/membership/members/.

Piron, Florence. 2018. “Postcolonial Open Access.” Preprint to be published in Open Divide: Critical Studies on Open Access, edited by Ulrich Herb and Joachim Schopfel. Sacramento, CA: Litwin Books. https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/handle/20.500.11794/16178.

Public Knowledge Project-Simon Frazier University Library. 2014. Open Journal Systems. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://pkp.sfu.ca/ojs/.

Raju, C. K. 2010. “Ending Academic Imperialism: A Beginning.” http://ckraju.net/papers/Academic-imperialism-final.pdf

Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale (RILM). 1966–2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.rilm.org/.

Sabharwal, Sanjeeve, Nirav Patel, and Karanjeev Johal. 2014. “Open Access Publishing: A Study of Current Practices in Orthopaedic Research.” International Orthopaedics 38, no. 6 (June): 1297–1302.

Sangeet Galaxy Foundation. 2012–. Sangeet Galaxy. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://sangeetgalaxy.co.in/.

Sarath, Ed. 2016. “Transforming Music Study from Its Foundations: A Manifesto for Progressive Change in the Undergraduate Preparation of Music Majors.” College Music Society, https://www.music.org/pdf/pubs/tfumm/TFUMM.pdf.

Shanghai Conservatory of Music and CHIME (Leiden, Netherlands). 1990–. CHIME: Journal of the European Foundation for Chinese Music Research. Accessed April 20, 2021. http://home.wxs.nl/~chime/.

Socha, Beata. 2017. “How Much Do Top Publishers Charge for Open Access?” Open Science (April 20). http://web.archive.org/web/20210227181230/ https://openscience.com/how-much-do-top-publishers-charge-for-open-access/.

Society for Ethnomusicology. 2015–. Ethnomusicology Translations. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/emt/index.

South African College of Music, University of Cape Town. 2004–. Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rmaa20/current.

South African Society for Research in Music. 2006–. SAMUS: South African Music Studies. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://journals.co.za/journal/samus1.

Stop Predatory Journals, 2017. “Stop Predatory Journals.” Last updated February 19, 2017. https://predatoryjournals.com/.

Suber, Peter. 2012. Open Access. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

The Royal Danish Society. 2003–20. Carl Nielson Studies. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://tidsskrift.dk/carlnielsenstudies/about.

Universidad de Chile. 1945–. Revista musical chilena. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://revistamusicalchilena.uchile.cl/.

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. 2010–. Revista Brasileira de Música. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://revistas.ufrj.br/index.php/rbm.

University of Vienna. 2015 –. Translingual Discourse in Ethnomusicology. Accessed May 9,2021. https://www.tde-journal.org/index.php/tde/index.

Warf, Barney. 2011. “Geographies of Global Internet Censorship.” GeoJournal 76: 1–23.

Weber, Steven. 2004. The Success of Open Source. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Whitacre, Eric. 2021. “Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir.” Accessed April 21, 2021. https://ericwhitacre.com/the-virtual-choir.

Willinsky, John. 2005. The Access Principle: The Case for Open Access to Research and Scholarship. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Willinsky, John, and Ranjini Mendis. 2007. “Open Access on a Zero Budget: A Case Study of Postcolonial Text.” Information Research 12, no. 3 (April). http://informationr.net/ir/12-3/paper308.html.