Abstract

Although it has gained considerable scholarly attention within the last three decades, music performance anxiety (MPA) remains a topic most musicians prefer to avoid due to fear of judgment. Yet, the experience of MPA is prevalent among adult and adolescent musicians, as evidenced by the studies of Fishbein and Middlestadt (1988), van Kemenade et al. (1995), Fehm and Schmidt (2006), and others. Moreover, Kenny and Osborne (2006) have suggested that adolescence is a critical period for the onset of MPA. Among others, Miller and Chesky (2004) have demonstrated the centrality of negative cognition in MPA, and in accordance with these findings, some studies have yielded promising results for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as an effective MPA treatment. Given the frequency of MPA’s onset in adolescence and the accessibility of CBT techniques, in this article I propose several adapted CBT methods for the private music lesson, enabling pedagogues to add cognitive and behavioral goals to weekly practice assignments.

Vincent P. Benitez

Introduction

Despite the prevalence of music performance anxiety (MPA hereafter) and the considerable scholarly attention it has gained within the last three decades, it remains a topic most musicians prefer to avoid. McGrath et al. explain: “Because many people perceive MPA as a personal shortcoming rather than something that can be dealt with, these symptoms are often left untreated. Similarly, sometimes those of us who feel the anxiety deeply or intensely are unwilling to talk about it with others—for fear of judgment or even fearing fear itself” (McGrath et al., 2017, p. 4). However, the tendency of MPA sufferers to engage in maladaptive coping behaviors (Park, 2010), the possible correlation between MPA and depression (Clark & Watson, 1991; Lonigan et al., 1994), and the potential for high-MPA musicians to abandon their field (Kenny & Osborne, 2006; Steptoe & Fidler, 1987) indicate that MPA is a topic worthy of inquiry. Upon defining MPA and exploring its epidemiological factors, this article contends that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be efficacious in treating MPA. The article concludes with practical suggestions for the private music teacher.

Music Performance Anxiety: Definitions and Clarifications

As with any psychological experience, MPA is complex because its severity and symptoms vary from individual to individual. Due to the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association’s relatively sparse information on the subject, anxiety experts have attempted to provide more substantive definitions of MPA, comparing the experience with other forms of anxiety. For so narrow a topic, scholarly perspectives on MPA vary widely. However, each definition acknowledges the multifaceted nature of MPA, noting its somatic, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional manifestations (McGrath et al., 2017, p. 2; Steptoe, 2001, p. 295). Some researchers have merged MPA’s somatic symptoms with its behavioral symptoms, thereby creating a three-factor model, but for the purpose of understanding the literature, all four categories will be briefly discussed.

In 1997, the Fédération Internationale des Musiciens (FIM) carried out one of the largest MPA studies by surveying members from 56 orchestras throughout the world (James, 1997). Rapid heartbeat (67%), sweating hands (56%), and muscle tension (56%) were the most reported somatic symptoms (Steptoe, 2001, p. 295). Similarly, a survey of students and faculty at the University of Iowa School of Music found that 57% of respondents experienced rapid heart rate, while 43% reported sweating as the most prominent symptom (Wesner et al., 1990). Shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea, and trembling have also been identified as common physical symptoms of MPA. These somatic effects of MPA often result in behavioral disturbances, such as lifted shoulders, pacing, avoiding performance, or even backing out of performance commitments.

In addition to physical and behavioral symptoms, the FIM subjects reported cognitive ones, the most common of which was a loss of concentration (49%). Even more noteworthy, 63% of the Wesner et al. (1990) respondents named poor concentration as the most problematic MPA symptom. Lack of concentration often results from intrusive thoughts or concerns about the audience, prior preparation, or physical symptoms, and can lead to lapses in memory or a flat performance (McGrath et al., 2017, pp. 37–38). Lastly, emotional symptoms are frequently reported by musicians with MPA. Kenny (2010) uses the term “anxious apprehension” to describe the cluster of negative, future-oriented emotions that commonly plague those with MPA. Anxious apprehension includes feelings of helplessness, a focus on oneself, and doubts about one’s ability to cope (Kenny, 2010, p. 427).

Even as “musical performance anxiety” is most commonly seen in the literature, it should be noted that some have used this term interchangeably with “stage fright” (Salmon, 1990; Wilson & Roland, 2002). However, Kenny prefers the term “musical performance anxiety” over “stage fright,” since stage fright generally refers to the relatively rare and sudden onset of panic on stage that leads to breakdown in performance (Kenny, 2010, p. 430). In contrast, MPA can arise many days before a performance and persist in ruminative form days afterward. Steptoe adds that stage fright denotes panic in front of a large audience, whereas MPA can occur in smaller settings, such as an audition or jury (Steptoe, 2001, p. 292).

There is also disagreement as to whether MPA should be classified as a specific type of social phobia. The American Psychological Association (APA) defines performance anxiety as “apprehension and fear of the consequences of being unable to perform a task or of performing at a level that will raise expectations of even better task achievement” (American Psychological Association, 2020). It goes on to list exams, public speaking, musical performance, participation in meetings, and eating in public as examples of situations that could elicit performance anxiety. According to the APA, social anxiety is closely related to performance anxiety, but differs in that social anxiety involves a fear of social situations which could lead to embarrassment or being viewed negatively by others (American Psychological Association, 2020). Whereas performance anxiety is concerned specifically with the consequences of a poor performance, social anxiety involves an ongoing fear of public humiliation.

If either performance anxiety or social anxiety causes significant distress or hinders regular functioning, it may be diagnosed as social anxiety disorder (SAD), previously known as “social phobia.” Therefore, APA classifies performance anxiety as a subset of, and even a precursor to, social anxiety disorder. Similarly, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines performance anxiety as a subset of social anxiety disorder, as does Barlow’s Anxiety and its Disorders, an esteemed source on the treatment of anxiety and panic disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, 300.23; Barlow, 2002, p. 75, 457).

Kenny (2010) offers a more comprehensive perspective on the difference between MPA and social phobia. She acknowledges that MPA and SAD could have common roots, citing the 1991 study of Clark and Agras, which found that 95% of a sample of adult musicians with high MPA qualified for a SAD diagnosis. However, she describes four factors that separate MPA from SAD, not only in severity but also in essence (Kenny, 2010, pp. 431–433). First, those with MPA are likely to have higher expectations of themselves to the extent that they may fear self-criticism even more than the evaluation of an audience, which would be of utmost concern to those with social phobia. Whereas social phobia sufferers fear others, MPA seems to exhibit a fear not only of embarrassment or failure but also of fear itself. Second, while untreated social phobia typically leads to an individual’s withdrawal from anxiety-inducing scenarios, even musicians who struggle with MPA tend to exhibit a “continued commitment to the feared performance situation,” despite great discomfort (Kenny, 2010, p. 431). Third, those with social phobia tend to demonstrate anxiety toward common tasks that are neither cognitively nor physically demanding, such as eating or introducing oneself. Performing musicians, however, are expected to exercise considerable motor skill and mental acuity while maintaining a composed disposition on stage. Fourth, social phobia often creates the illusion of an imaginary audience, wherein the individual feels as though everyone is watching and judging them, whereas in MPA, the musician truly is being watched and often, judged as well. Based on these four differences, Kenny concludes that MPA may be isolated or may occur concurrently with other anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety disorder (Kenny, 2010, p. 434).

Music Performance Anxiety: Epidemiological Factors

Anxiety disorders are the most frequently occurring mental health issue in adults, children, and adolescents alike in the US (Kenny, 2010, p. 426), so it is no surprise that the pervasiveness of anxiety is reflected in the musical community. In a national survey assessing the medical problems of 2,122 professional orchestral musicians (Fishbein & Middlestadt, 1988), “stage fright” was the most prevalent issue reported (24%), followed closely by lower back (22%), neck (22%), and shoulder (20%) pain. Acute anxiety was reported by 13% of participants. The following year, a survey of 48 orchestras by Lockwood (1989) revealed uncannily similar numbers, with 24% reporting frequent stage fright and 13% acute anxiety. Interestingly, later surveys that described MPA in less severe terms (“performance anxiety” as opposed to “stage fright”) produced more radical results. In a self-report study of 155 professional orchestra musicians across the Netherlands (van Kemenade et al. 1995), 58% of participants reported current or past experience with MPA that was severe enough to affect their professional and personal lives. In the aforementioned FIM survey, 70% of musicians across 56 professional orchestras reported anxiety severe enough to interfere with their performance (James, 1997).

The majority of the MPA literature has studied either instrumentalists only or grouped vocalists and instrumentalists, but very few performance anxiety studies have concentrated on vocalists alone. Perceiving a need for MPA research specific to singers, Ryan and Andrews conducted a study in 2009 involving 201 members from 7 semiprofessional choirs across Canada. (The researchers defined “semiprofessional choir” as one that performs high-level repertoire and is paid often, but not always, for its concerts.) Upon surveying participants through the researcher-developed “Choral Performance Experience Questionnaire,” Ryan and Andrews discovered that 57% experienced moderate levels of performance anxiety during at least half of their performances. However, only 7% reported high levels of anxiety during choral performances. Few choir members in Ryan and Andrews’ study indicated seeking medical assistance for MPA treatment, whereas instrumentalists in similar studies have admitted to the use of medication preperformance (Fishbein et al., 1988). Although Ryan and Andrews’s study found that most participating vocalists endured only moderate levels of MPA, it would be naïve to assume that vocalists’ personal and professional lives are not affected by MPA. When asked whether MPA had affected their life, career, or musical participation, 26% of Ryan and Andrews’s participants answered yes, with statements such as: “I may have considered music on a professional level if not for performance anxiety”; “I will not try out for a musical even though I would like to perform with them”; and “I feel [MPA] has limited me in every way” (Ryan & Andrews, 2009, pp. 117–118). In another vocal-specific study, 64% of 84 community choir singers stated that MPA inhibited them from performing more frequently as a soloist (Stothert, 2012).

Although there is considerable need for further study on the occurrence of MPA in young children (Kenny & Osborne, 2006, p. 104), certain studies have shown that adolescent musicians experience MPA similarly to adult, professional musicians in prevalence and reported symptoms. Shoup’s survey (1995) of 425 high-school and junior high-school band and orchestra students found that the proportion of students displaying MPA symptoms was approximately equal to that of professional musicians. Fehm and Schmidt (2006) found that approximately 1/3 of 15 to 19-year-old music students in Germany were adversely affected by performance anxiety. Osborne and Kenny (2008) found that, as with adults, trait anxiety (a propensity toward anxiety across many situations) is a significant predicting factor of MPA in high-school and college-level music students.

Not only does MPA manifest itself similarly in adults and adolescents, but Kenny and Osborne have suggested that adolescence could actually be a critical period for the onset of MPA. In their 2006 study, Kenny and Osborne asked 381 music students from performing-arts high schools to provide written descriptions of their worst performance experience. To create a consistent framework, the researchers gave specific guidelines, asking participants to indicate their age at the time, the venue and audience, and the feedback they received following the performance. Statements from the self-reports were classified into six domains: (1) situational factors, (2) behavioral factors, (3) affective symptoms, (4) cognitive symptoms, (5) somatic symptoms, and (6) outcome. Kenny and Osborne discovered a rise in performance anxiety levels in the 8th grade, with a peak in the 10th grade, and a gradual decline to pre-grade 8 levels thereafter. The researchers attribute this curvilinear trend in MPA levels to the development of formal operational thought, a cognitive shift associated with adolescence (Kenny & Osborne, 2006, p. 106). Identified by Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget and Bärbel Inhelder in 1958, formal operational thought involves an increase in “retrospection and self-evaluation” to the extent that adolescents believe others are as preoccupied with their thoughts and appearance as they are (Kenny & Osborne, 2006, p. 106).

As discussed above, MPA is widely recognized as involving somatic, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional symptoms. Yet, the precise interaction of these symptoms remains unclear. Some psychologists view the somatic symptoms as most fundamental to MPA, contending that physiological arousal initiates a chain reaction resulting in anxious thoughts (Zinn et al., 2000, p. 69). Conversely, many cognitive behaviorists purport that performance anxiety is initiated by cognitive appraisals of the perceived threat, or performance scenario (Bruce & Barlow, 1990; Osborne & Franklin, 2002; Kirchner, 2003). Still others have shown evidence that these symptom groups are equally influential because they all become “highly activated and synchronized” under highly stressful conditions (Salmon, 1990, p. 3).

Although theories surrounding the interaction of symptom groups vary, a growing number of studies, echoing Bruce and Barlow, have found the cognitive/emotional symptom group to be more fundamental to the experience of MPA than was originally supposed. Miller and Chesky (2004) examined the intensity and direction of cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and self-confidence across different performance scenarios. The researchers also evaluated student and teacher perceptions of the degree to which MPA hindered students’ performances. Student volunteers were gathered from the University of North Texas College of Music and were tested using four assessment tools, including modified versions of the Competitive Trait Anxiety Inventory-2 and Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2. Miller and Chesky found that trait cognitive intensity was significantly higher than trait somatic intensity for private lesson, pre-jury, and jury performance scenarios.

In Kenny and Osborne’s (2006) study of high-school music students based on written descriptions of negative performance experiences, the most significant predictive factor of MPA was trait anxiety, suggesting a predisposition toward negative performance experience. Trait anxiety was closely followed by the factor of negative cognition, which was measured by statements such as, “I was very worried about the performance”; “I worried that my teacher would be disappointed in me”; or “the judges were intimidating and psyched me out” (Kenny & Osborne, 2006, p. 109). Students with higher negative cognition scores rated higher in MPA than students with lower ones. It is not surprising that trait anxiety should appear alongside negative cognition as an essential factor in performance anxiety. According to the American Psychological Association, individuals with high trait anxiety tend to perceive the world as more dangerous or threatening than those with low trait anxiety (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2020). Consequently, “highly anxious individuals tend to overestimate the likelihood and consequences of negative evaluation compared with low anxious people” (Osborne & Kenny, 2008, p. 457). Those with high trait anxiety also tend to exhibit state anxiety (transitory, emotional anxiety in response to an event) in situations that would seem relatively non-threatening to those with low levels of trait anxiety (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2020). This seems to be congruent with the theories of Osborne and Franklin (2002) and Kirchner (2003), which identify cognitive evaluation of the situational threat as the catalyst of MPA. However, even proponents of other viewpoints would struggle to deny the power of cognitive appraisal before, throughout, and after a musical performance. Kenny describes cognitive appraisal as

a complex process that in a music performance context involves assessment of the demands of the performance, the personal resources that can be accessed to meet the demands, the possible consequences of the performance, and the meaning of those consequences to the musician. (Kenny, 2010, p. 426)

Kenny goes on to illustrate the connection between negative cognition and emotion with an account from a 22-year-old male clarinetist. When anxiety invades cognitive appraisal, negative thoughts give rise to anxious emotions, and these emotions elicit further negative cognition, resulting in a seemingly uncontrollable spiral. The clarinetist writes:

I suffer from music performance anxiety…. I don’t sweat or get shaky or anything like that. I am just so worried about what people think if it goes wrong. Once I go out there, I concentrate so hard to relax and it goes the other way and then I end up being really casual about it and probably not concentrating enough…. Before a concert, it’s a complete nightmare. I don’t think there is anything I can do with it, so I just leave it at that. (Kenny, 2010, p. 436)

The perceived lack of control that accompanies prolonged MPA is evident, and it is possible that feelings of hopelessness could cause some musicians to abandon the field. In 1987, Steptoe and Fidler conducted a study that compared amateurs, students, and professionals in the music field. Their findings indicated higher levels of performance anxiety among students compared with professional musicians, and within the group of professionals, MPA was negatively correlated with age and amount of performance experience. Initially, these results appear to demonstrate that repeated exposure to performance settings leads to a reduction in MPA levels. However, Steptoe and Fidler suggest that these results could also reflect that high-MPA musicians may become so overwhelmed by the pressures of a competitive orchestra job that they give up early in their career (Steptoe & Fidler, 1987, p. 248). In the case of younger musicians, some might lose hope of pursuing music professionally, settling for another career. In Kenny and Osborne’s (2006) study of high-school students’ self-reports, the students who reported that they wanted to be a professional musician had lower MPA scores than those who answered “no” or “I don’t know.” Based on this finding, “it is possible that students reject or are uncertain of a career as a professional musician because of the discomfort associated with high MPA” (Kenny & Osborne, 2006, p. 107).

While some may abandon music altogether, other musicians may become dependent on medication to achieve success in their career. Research shows that a significant number of those with high MPA who do decide to pursue music do so with the assistance of beta blockers. Beta-adrenergic blocking agents such as propranolol and metoprolol block epinephrine (adrenaline), causing the heart to beat more slowly and consequently, lowering blood pressure. Although the benefits and dangers of beta blockers are debated, music educators generally share concerns for how many musicians use these medications without a prescription. In the 1988 survey by Fishbein and Middlestadt, 27% of orchestral musicians admitted to having used beta blockers, and 70% of these reported that they had obtained the drugs informally (without a prescription). Outside of legal and ethical concerns, the informal transmission of beta blockers is especially problematic for students, who may not understand the potential side effects, which include light-headedness, fainting, weakness, nausea, and adverse effects on the respiratory system (Patston & Loughlan, 2014, pp. 6–7).

Furthermore, beta blockers target only the somatic symptoms of performance anxiety. Although beta blockers have been shown to successfully calm the panic responses of the autonomic nervous system, these medications do not directly combat the cognitive-emotional symptoms that Bruce and Barlow, Osborne and Franklin, Kirchner, Miller and Chesky, and Kenny have reported as central to the experience of MPA. These researchers assess that, given the debilitating nature of cognitive anxiety, prevention and intervention strategies should include a cognitive-based approach and not only solutions aimed at suppressing somatic symptoms.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: Efficacy for Musicians

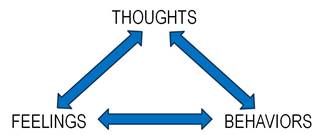

In recent years, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has gained an impressive empirical base and grown almost exponentially in research interest since 1980 (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, p. 1). Proponents of CBT recognize the interrelation between one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, commonly represented by the figure below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cognitive-behavioral triangle

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is based on three main principles. First, cognitive-behavioral therapists aver that the content and process of an individual’s thinking can be accessed and understood by that individual. This differs starkly from psychoanalytic theory, which holds the subconscious mind largely responsible for erroneous thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Second, CBT claims that an individual’s thoughts mediate their emotional and behavioral responses to a given situation. In other words, a person’s thoughts play a critical role in determining the way they feel and behave. Third, because thoughts are knowable and shape responses, individuals may intentionally alter undesirable thought processes, thereby altering undesirable responses (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, pp. 5–6). The goal of cognitive-behavioral therapists is to equip clients to do just that by implementing cognitive strategies, such as thought tracking and mental rehearsal, as well as behavioral strategies, like exposure to the feared situation (behavior rehearsal). Given the diversity of symptoms experienced in MPA, it is not surprising that the multifaceted CBT has proven beneficial as a combative strategy.

Clark and Agras (1991) made what is perhaps the most compelling case. The researchers recruited 94 musicians that met the criteria for social phobia in the form of MPA, dividing them into three treatment groups: CBT and placebo, CBT and buspirone (a beta blocker medication), and buspirone alone. The control group was given placebo medication. The two CBT groups showed greater pre to post fall (decreased MPA after treatment) than the placebo and buspirone groups. Furthermore, CBT alone (CBT and placebo) improved performers’ confidence more than any of the other three groups, suggesting that CBT alone may be a more successful treatment approach than CBT combined with beta blocker use.

In one study comparing the efficiency of CBT and behavior rehearsal (Kendrick et al., 1982), the researchers facilitated small group meetings and homework for 53 pianists with extreme MPA. Over the 3-week period, both treatment groups improved more than the control group on the Performance Anxiety Self Statement Scale (PASS), as well as performance quality. Pianists in the CBT group, however, demonstrated greater improvement in physical signs of anxiety than those in the group that implemented behavioral rehearsal alone. The CBT group also showed more improvement than the behavior rehearsal group on the Expectations of Personal Efficacy Scale (EPES), indicating that an intentional restructuring of negative cognitions can lead to an increased sense of control over performance scenarios, thereby strengthening the musician’s confidence in their abilities. This is consistent with the Mor et al. (1995) study, which found that perfectionism combined with low levels of personal control produced higher levels of performance anxiety.

A more recent study by Osborne et al. (2007) assessed the effectiveness of CBT programs for 23 adolescents with high MPA from selective high schools. The students were randomly assigned to either a 7-session CBT intervention program or a behavior-exposure only control group. The CBT program involved education on (1) psychology and cognition, (2) goal setting, (3) cognitive restructuring, (4) physical relaxation training, and (5) situation exposure. Interestingly, CBT did not appear to improve performance quality in comparison with the behavior-exposure group, but the CBT group did show significant improvements in self-reported MPA. The most anxious students were adherents to the program, while those with only mild or moderate levels of MPA were less likely to complete the therapy tasks. Based on these findings, the researchers conclude that behavioral exposure alone could improve performance quality for students with mild MPA, but those with more severe performance anxiety would likely benefit from a specialized cognitive-behavioral intervention program.

It should be noted that some adolescent musicians may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy or another form of therapy in a clinical setting. Particularly, those with more extreme symptoms that pervade multiple areas of life, not only music performance, could be facing a personality or mood disorder that necessitates professional attention. However, students whose anxiety is primarily associated with music performance could benefit considerably from the implementation of performance anxiety strategies in a private music lesson setting. In chapter 8 of Performance Anxiety Strategies, entitled “Especially for Teachers,” McGrath et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of cognitive self-regulation and training music students to focus on positive outcomes when negative cognitions arise. Since years of negative thinking habits cannot quickly be undone, it is critical that teachers “model positive thoughts and teach students to accurately assess their abilities from the beginning and throughout their music-learning lives” (McGrath et al., 2017, p. 123). By doing so, private lesson instructors can help students to fight MPA in its early stages, saving them future frustration and discouragement.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: Pedagogical Insights

Intentionally preventing and combatting MPA can begin with simply avoiding behaviors and comments that could inadvertently initiate or exacerbate negative thinking patterns in students. Understanding a student’s personality strengths and hinderances is important because seemingly innocuous phrases could be harmful to students who struggle with low self-efficacy and tendencies toward negative cognition (McGrath et al., 2017, pp. 124–130). For example, warning a student that they “won’t get it unless they practice” could inhibit creativity in problem solving. Passive, indifferent students may need to be motivated in such a way, but for perfectionistic students, teachers would do better to inquire about the student’s practicing routine, offering ideas for how to practice effectively.

McGrath et al. later explain that even the common affirmation, “I think you’re a great person no matter how well you perform,” might not be as helpful as a teacher intends. Although expressed appreciation for a student’s person might enhance their general self-esteem, it does not speak to their musical ability or the performance task at hand. Such a statement could even lead students to believe that the teacher has given up on their performance potential and has resorted to consolation by means of vague compliments. Lastly, though the teacher claims performance and self-worth are not connected, mention of the two in the same sentence could cause an insecure student to suspect otherwise (McGrath, et al., 2017, p. 130).

Private lesson teachers may also consider more direct means of equipping students to cope with performance anxiety. In Evidence-Based Practice of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, a timely volume connecting CBT research with clinical practice, authors Dobson and Dobson (2017) provide a practical framework for implementing CBT treatment. Their guidance, while intended for clinicians, will be borrowed and adapted in the remainder of this article for the benefit of private music lesson teachers and perhaps, even music students’ personal benefit. The authors explore behavioral strategies first under the categories, “Increasing Skills” and “Decreasing Avoidance.” They later discuss techniques aimed at improving cognition, dividing these into three categories: “Identifying Targets,” “Addressing Negative Thinking,” and “Working with Core Beliefs and Schemas.” For practical purposes, the cognitive strategies will be examined first, followed by strategies aimed at improving behavior.

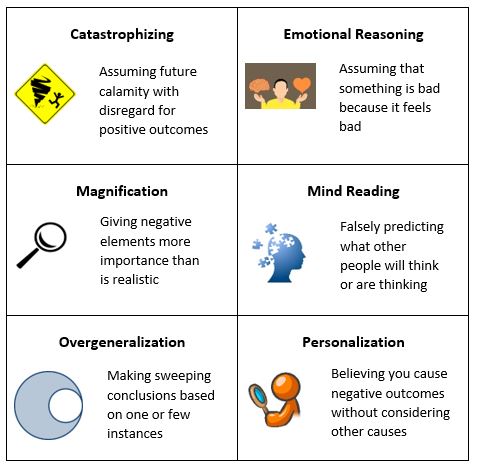

In “Identifying Targets,” Dobson and Dobson (2017, pp. 155–171) describe how therapists can guide their clients through assessing negative thoughts, beginning by simply educating them about the connection between thoughts, feelings, and emotions. The therapist can further a client’s understanding of cognitive processes by describing various kinds of thought distortions, or unhelpful thinking patterns (Figure 2). One of the most common cognitive distortions among depression and anxiety clients is Overgeneralization, which involves making a sweeping conclusion based on one negative experience. In a music performance context, this might look like a student claiming they never perform well on the basis of one poor performance. Another example of cognitive distortion is Magnification, which gives an isolated factor more importance than is realistic. For example, the student may have faltered during one passage of a multi-movement work but feels as though they botched the entire performance.

Figure 2. Common Cognitive Distortions. (Created by the author using Dobson & Dobson’s Evidence-Based Practice of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (2017) and public domain/creative commons imagery.)

Once a client has been given information on the power of negative thinking and a reference for categorizing cognitive distortions, the therapist asks the client to use a journal or worksheet to track negative thoughts, as well as the emotions and behaviors that accompany each thought. Clients are also encouraged to classify the cognitive distortion if possible, and to rate the strength of their emotion in response to the negative thought. Therapists may then evaluate the patient’s dysfunctional thought record, looking for repeated patterns and strong emotional responses to decide which thoughts to address first. Later, cognitive-behavioral therapists help clients to understand their negative thoughts, combat them, and think in healthier ways.

After tracking thoughts for a predetermined number of days, the therapist may begin to address negative thoughts by discussing with their client evidence for and against each thought (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, pp. 173–184). Many times, a thought is founded in reality but skewed based on adverse emotional reactions. For example, an adolescent piano student might believe he never performs well from memory and has no hope as a professional musician. The student may truly need to improve in performing from memory, but perhaps overcoming this obstacle is all that prohibits him from a successful career in music. By talking with students about their thought patterns, private lesson teachers can help students replace negative thoughts with positive alternatives. In addition to guiding the student in evaluating the evidence for and against an unhealthy thought, teachers should ask the student to consider the implications of thinking that way. The question, “If that thought were true, what would be the result?” may help student and teacher alike reach the heart of the issue (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, pp. 191–192). Consider this conjectural dialogue:

TEACHER: If you really did bomb your upcoming recital performance, what would happen?

STUDENT: Everyone would think I was a failure because I always mess up in performances.

TEACHER: What do you mean by a “failure?”

STUDENT: People will think I’m not any good at music and shouldn’t try anymore.

Just based on two inquiries, the teacher has discovered that the student reduces success in music to whether he performs flawlessly in solo recitals. Notice also that the teacher may have uncovered a cognitive distortion, unless it is true that the student truly has performed poorly in every recital.

Examining the implications of a reported thought reveals a client’s broad inferences about themselves, the world, or others, which in turn reflect their core beliefs and schemas. Schemas are “relatively permanent notions about objects, people, or concepts” that help individuals process and interpret information (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, p. 202). Over time, personal experiences and accompanying emotions create semi-permanent ideas that result in behaviors that either support or challenge these ideas. Expanding on the work of Piaget and Warden, who coined “schemas” in 1926, Beck theorized that negatively biased schemas have a significant role in the development of mental disorders, primarily depression and anxiety (Beck & Haigh, 2014). In essence, a schema is not just an isolated negative thought, but a theme that may undergird several thoughts and beliefs. If the theme is founded in a flawed perception of reality, dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors will result.

Upon identifying and discussing the client’s cognitive distortions, negative schemas, and disadvantages of both, therapists may work with clients to replace each negative thought with a realistic or more beneficial alternative. Once a new thought is agreed upon by therapist and client, the therapist asks the client to name its advantages and disadvantages, as they did with the original thought. Dobson and Dobson suggest asking the client to write replacement thoughts next to automatic, negative thoughts on their dysfunctional thought record (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, p. 186). In the case of a music student, the record might now look something like this (Figure 3):

Figure 3. Dysfunctional Thought Record (DTR), as proposed by Dobson and Dobson (2017). Examples added by author.

|

Situation (date/event) |

Automatic Thought |

Emotions |

Behaviors/Actions |

Alternative Thought |

Consequences |

|

Poor performance at school jazz band audition |

“My teacher will be so disappointed in me.” |

- Inadequate - Guilty |

- Avoid telling teacher |

“My teacher may be disappointed for me, but he understands and will not blame me.” |

- Problem solving with teacher - Performance goal setting |

|

School choir recital |

“I always let nerves take over.” |

- Anxious - Hopeless |

- Avoid preparation for next performance |

“I’m in control of my thoughts, and I gain confidence with each performance experience.” |

- Increased confidence - Increased motivation in vocal lessons |

|

Unexpectedly asked to play for family |

“If I can’t play anything from memory, I’m not a real musician.” |

- Humiliated - Insecure |

- Decreased practice - Inattention in lessons |

“My family will appreciate hearing me play whether it is polished or not.” |

- Personal enjoyment of sharing music - Others’ listening enjoyment |

An awareness of negative cognitive patterns and their adverse effects may be enough to inspire alternative ways of thinking in music students, but some may require more practice than others. The dysfunctional thought record provides a helpful reference for teacher and student to combat unhealthy thoughts about performance as they arise, and with time, ideas that debilitate performance potential will be replaced by those that improve performance, strengthen self-efficacy, and increase enjoyment of music making. Throughout the process, it is important to encourage students to think positively. In The Balanced Musician, McAllister writes, “If we give ourselves directions framed in the negative, then we will be much more likely to stay tense and even do exactly what we are telling ourselves not to do” (McAllister, 2013, p. 87). What performers tell themselves before and during a performance has significant potential for harm or good. Reframed in a positive manner, thoughts like (1) “I hope I don’t tense up” become “I will relax my shoulders”; (2) “I hope I don’t miss my entrance” becomes “I will watch my accompanist attentively and enter appropriately”; and (3) “Don’t rush this passage,” becomes “Play slowly and evenly.” As opposed to self-talk that regularly warns against negative outcomes, positive thinking enhances performance potential, improves self-efficacy, and increases enjoyment in music making.

Because proponents of cognitive-behavioral therapy recognize the apparent connection between thoughts and behaviors, they seek not only to reform negative thought processes and judgmental self-talk but also to shape behaviors. Evidence-Based Practice of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy discusses the behavioral strategies of CBT in two categories: increasing skills and decreasing avoidance (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, pp. 109–134; 135–154). Increasing skills includes a wide variety of activities dependent upon the client, their presenting problem, and their degree of discomfort. For musicians struggling with MPA, skills desirable for improving performance generally fall into one of two categories: Preperformance Routine or Supportive Lifestyle. An optimum preperformance routine is dependent on each performer and is therefore reached through experimentation. Teachers can work with students to develop a preperformance plan, including elements such as (1) adequate sleep the night before, (2) control of interaction with others prior to going on stage, (3) relaxation through breathing exercises, and (4) a vocal or instrumental warm-up (Wilson & Roland, 2002, p. 57). Supportive lifestyle skills are those that are helpful for general stress management. This could include regular physical exercise to release tension, avoidance of certain foods and drinks that cause fluctuations in concentration, and healthy sleep habits. Even peripheral factors, such as family conflict and academic demands, could have an unrealized, adverse effect on a student’s approach to performance (Wilson & Roland, 2002, p. 58).

Brainstorming preperformance routine and supportive lifestyle strategies is an intuitive process for most teachers and adolescent students, but decreasing avoidance requires more concentrated effort. It is no surprise that avoiding performance is a common behavioral tendency of MPA, as “avoidance is a central feature of all the anxiety disorders” (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, p. 136). The most obvious way in which teachers can help music students overcome avoidance is through repeated performance exposure. Dobson and Dobson advise developing hierarchies, which are structured, and gradual steps from low-level anxiety situations to higher ones (Dobson & Dobson, 2017, p. 141). A hierarchy composed of three categories—easy, moderate, and difficult—is sufficient in most cases and offers a balance of structure and flexibility. Writing specific performance opportunities in each category creates a list from which student and teacher can generate performance exposure goals, beginning with nonthreatening scenarios, such as playing background music or singing at a nursing home, and moving to more intimidating performances, like solo competitions. Tracking thoughts, emotions, and behaviors before, during, and after even small performances is important because it helps students to approach performing with a helpful mindset and maintain a record of their progress.

Private lesson teachers have one-on-one time with students and a clear advantage in helping young musicians develop personalized strategies to combat MPA. However, the influence of middle-school and high-school ensemble directors ought not be minimized, especially since school ensembles serve as the primary exposure of musical instruction to many students. Researchers including Passer (1983), Roberts (1986), and Smith et al. (1995) have offered insightful studies on the role of coaches in heightening or alleviating performance anxiety in young athletes. Given the early onset, considerable frequency, and negative consequences of MPA, applying parallel studies to conductors and school music ensembles would be a worthy undertaking. Armstrong and Armstrong (1996), Sternbach (2008), Adams (2019), and others have offered advice to music teachers that desire to cultivate a positive rehearsal environment, but the impact of such strategies should be investigated in future research.

Concluding Remarks

Music performance anxiety is a multifaceted and troublesome experience for many musicians that may hinder their enjoyment and success in music, or even deter them from a music career. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has proven efficacious in treating many anxiety and depressive disorders and has consequently become a vital asset to clinical psychological practice. Research in MPA increasingly reveals the benefits of addressing not only somatic symptoms but also the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms of performance anxiety, suggesting CBT as a viable treatment for MPA. Given the frequency of MPA’s onset in adolescence and the accessibility of CBT techniques, music teachers can adapt CBT methods for the private lesson, adding cognitive and behavioral goals to weekly practice assignments and musicianship goals. In doing so, they will increase students’ self-efficacy, performance potential, and enjoyment of music. They might even save a rising artist.

References

Adams, K. (2019). Developing growth mindset in the ensemble rehearsal. Music Educators Journal 105(4), 21–27. doi:10.1177/0027432119849473.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Performance Anxiety. APA Dictionary of Psychology. performance anxiety – APA Dictionary of Psychology.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Social Anxiety. APA Dictionary of Psychology. social anxiety – APA Dictionary of Psychology.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Social Phobia. APA Dictionary of Psychology. social phobia – APA Dictionary of Psychology.

Armstrong, S., & Armstrong, S. (1996). The conductor as a transformational leader. Music Educators Journal 86(6), 22–25. doi:10.2307/3398947.

Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its Disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. P. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory & therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734.

Bruce, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (1990). The nature and role of performance anxiety in sexual dysfunction. In v H. Leitenberg (Ed.), Handbook of Social and Evaluation Anxiety (pp. 357–384). New York: Plenum Press.

Clark, D. B., & Agras, W. S. (1991). The assessment and treatment of performance anxiety in musicians. American Journal of Psychiatry, 5(148), 598–605. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–336. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.100.3.316.

Dobson, D., & Dobson, K. S. (2017). Evidence-Based Practice of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Fehm, L., & Schmidt, K. (2006). Performance anxiety in gifted adolescent musicians. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(1), 98–109. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.11.011.

Fishbein, M. & Middlestadt, S. E. (1988). Medical problems among ICSOM musicians: Overview of a national survey. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 3(1), 1–8.

James, I. (1997). Fédération Internationale des Musiciens 1997 survey of 56 orchestras worldwide. London: British Association for Performing Arts Medicine.

Kendrick, M. J., Craig, K. D., Lawson, D. M., & Davidson, P. O. (1982). Cognitive behavioral therapy for MPA. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 50, 353–362. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.50.3.353.

Kenny, D. T. (2010). Negative emotions in music making: Performance anxiety. In P. Juslin, & J. Sloboda (Eds). Handbook of Music & Emotion: Theory, Research, Applications. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kenny, D. T., & Osborne, M. S. (2006). Music performance anxiety: New insights from young musicians. Advances in Cognitive Psychology 2(2–3), 103–112. doi:10.2478/v10053-008-0049-5.

Kirchner, J. M. (2003). A qualitative inquiry into musical performance anxiety. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 18(2), 780–782. doi:10.21091/mppa.2003.2015.

Lockwood, A. H. (1989). Medical problems of musicians. New England Journal of Medicine, 320, 221–227. doi:10.1056/nejm198901263200405.

Lonigan, C. J., Carey, M. P., & Finch, A. J. J. (1994). Anxiety and depression in adolescents: Negative affectivity and the utility of self-reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62(5), 1000–1008. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.62.5.1000.

McAllister, L. S. (2013). The Balanced Musician. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

McGrath, C., Hendricks, K. S., & Smith, T. D. (2017). Performance Anxiety Strategies: A Musician’s Guide to Managing Stage Fright. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Miller, S. R., & Chesky, K. (2004). The multidimensional anxiety theory. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 19(1), 12–20.

Mor, S., Day, H. I., & Flett, G. L. (1995). Perfectionism, control, & components of performance anxiety in professional artists. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 19(2), 207– 225. doi:10.1007/bf02229695.

Osborne, M. S., & Franklin, J. (2002). Cognitive processes in music performance anxiety. Australian Journal of Psychology, 54(2), 86–93. doi:10.1080/00049530210001706543.

Osborne, M. S., & Kenny, D. T. (2008). The role of sensitizing experience in MPA in adolescent musicians. Psychology of Music, 36(4), 447–462. doi:10.1177/0305735607086051.

Osborne, M. S., Kenny, D. T., & Cooksey, J. (2007). Impact of a cognitive-behavioural treatment program on music performance anxiety in secondary school music students: A pilot study. Musicae Scienteae, 11(2), 53–84. doi:10.1177/10298649070110s204.

Park, J. E. (2010). The relationship between musical performance anxiety, healthy lifestyle factors, and substance abuse among young adult classical musicians: Implications for training and education. EdD diss., Teachers College, Columbia University.

Passer, M. W. (1983). Fear of failure, fear of evaluation, perceived competence, and self-esteem in competitive-trait-anxious children. Journal of Sport Psychology 5(2), 172–188. doi:10.1123/jsp.5.2.172.

Patston, T., & Loughlan, T. (2014). Playing with performance: The use and abuse of beta-blockers in the performing arts. Victorian Journal of Music Education, 2014(1), 3–10.

Roberts, G. C. (1986). The perception of stress: A potential source and its development. In M. R. Weiss & D. Gould (Eds.), Sport for Children and Youths. (pp. 119–126). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ryan, C., & Andrews, N. (2009). An investigation into the choral singer’s experience of music performance anxiety. Journal of Research in Music Education, 57(2), 108–126.

Salmon, P. G. (1990). A psychological perspective on musical performance anxiety: A review of the literature. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 5(1), 1–11.

Shoup, D. (1995). Survey of performance-related problems among high school & junior high school musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 10(3), 100–105.

Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., & Barnett, N. P. (1995). Reduction of children’s sport performance anxiety through social support and stress-reduction training for coaches. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 16(1), pp. 125–142. doi:10.1016/0193-3973(95)90020-9.

Steptoe, A. (2001). Negative emotions in music making: The problem of performance anxiety. In P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Music and Emotion: Theory and Research. (pp. 291–308). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Steptoe, A., & Fidler, H. (1987). Stage fright in orchestral musicians: A study of cognitive & behavioural strategies in performance anxiety. British Journal of Psychology, 9(2), 241–249. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1987.tb02243.x.

Sternbach, D. J. (2008). Stress in the lives of music students. Music Educators Journal 94(3), 42–48. doi:10.1177/002743210809400309.

Stothert, W. N. (2012). Music performance anxiety in choral singers. Canadian Music Educator, 54(1), 21–23.

van Kemenade, J. F., van Son, M. J., & van Heesch, N. C. (1995). Performance anxiety among professional musicians in symphonic orchestras: A self-report study. Psychological Reports, 77, 555–562. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.77.2.555.

Wesner, R. B., Noyes, R. Jr., & Davis, T. L. (1990). The occurrence of performance anxiety among musicians. Journal of Affective Disorders, 18(3), 177–185. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(90)90034-6.

Wilson, G. D., & Roland, D. (2002). Performance Anxiety. In R. Parncutt & G.E. McPherson (Eds.), The Science and Psychology of Music Performance: Creative Strategies for Teaching and Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zinn, M., McCain, C., & Zinn, M. (2000). Music performance anxiety & the high-risk model of threat perception. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 15(2), 65–71.