Abstract

The music industry in the creative business cluster of Nashville, TN contributes over five billion dollars annually to the local economy. The companies within the business cluster have traditionally worked in a symbiotic manner similar to most creative business clusters where workers and organizations work together with competitors for mutual benefit. This phenomenon has created a tight-knit family-style environment and culture within and between firms in the market. In recent years, the rise of streaming revenue and the decline of past revenue streams have caused international publishing firms to look towards the Nashville market for acquisition to increase revenue and market share. This qualitative case study examined the experience of local Nashville workers who have experienced their small local firm’s acquisition and integration from an international firm. The purpose of this flexible design qualitative case study was to add to the body of knowledge on the Nashville creative business cluster and the role business culture may play in successful music publishing acquisitions within the market. Sixteen one-on-one interviews were conducted which resulted in three key themes pertaining to the culture within the Nashville market. The discovered themes combined with the existing research helped to establish critical recommendations for successful acquisition and integration within the Nashville music publishing market. With the completion of this study, international firms wishing to enter the Nashville market through acquisition and integration should have a better understanding of the issues that might arise.

J. Rush Hicks

Introduction

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization classified Nashville, Tennessee as one of the world’s music business centers and claimed that it holds the distinction of being deemed a music city (Baker, 2016). Nashville natives proudly use the term music city when referring to their town (Pollack, 2015). The city’s music business market could be classified as a business cluster due to what Park et al. (2019) defined as a geographic location where businesses locate near one another to work together for mutual benefit as well as compete within a market. The presence of major record labels in Nashville and the opportunities associated have created the phenomenon where songwriters, musicians, managers, artists, booking agents, and music publishers locate themselves in the market for individual and mutual benefit (Baker, 2016). Historically, royalties from the sale of albums and radio performances generated the majority of income for music publishers. Digital streaming royalties, however, have been quickly replacing the traditional revenue sources for publishers in recent years and have now become the largest source of music revenue worldwide (Datta et al., 2018). This growth of streaming revenues has created the phenomenon where larger multinational publishing companies are continually acquiring smaller publishers to increase market share to take advantage of the increases (Towse, 2017). As a result, publishers and songwriters are regularly experiencing their small local publishing companies being acquired by large international firms.

This case study focused on the experiences of Nashville music publishing workers within small local companies acquired by international firms and the issues associated with the phenomenon. Zakaria et al. (2017) explained that acquisitions fail to live up to the acquiring firm’s expectations in most instances. The common issues found in the past literature on acquisitions were experienced in the study, such as resistance to change, feelings of job insecurity, and lack of, or no, integration strategy (Bansal & King, 2020; Probst et al., 2007; Kets de Vries, 2015). The issues were all shown to be present in the Nashville market; however, the organizational market culture was shown to be the most distinct factor in the experience of acquisition and integration for workers. Upadhyay and Kumar (2020) described organizational culture as the values, norms, shared behaviors, and assumptions that influence the day-to-day operations of a firm. Organizational culture develops through the accumulation of workers’ experiences over time (Chelsey, 2020). There has been much literature on international acquisition and integration, but there has been little research on the topic within the Nashville music business cluster, specifically with music publishers and songwriters. Examining the experiences of workers within internationally acquired Nashville publishing companies adds to the literature on acquisitions in the Nashville business cluster as well as to the overall literature on acquiring firms within any business cluster.

Sixteen workers were interviewed for this study as participants. The participants had each worked for independent publishing companies in Nashville that had been acquired and integrated by a multinational firm. The participant’s accounts uncovered themes commonly associated with the experience. A solid background on the experience, as well as unique issues contributing to integration resistance, were displayed. The themes that were uncovered included Nashville’s family-style business culture, camaraderie and cooperation within the market, and the preference for small house environments for office locations. The results help to provide a guide and foundation for international firms wishing to enter the Nashville publishing business cluster market through acquisition.

Background

The landscape of the business world today is increasingly becoming more globalized as organizations are implementing strategies of development and growth that include acquiring firms across international borders (Zakaria et al., 2017). The pursuit of competitive advantages is the main driver for such acquisitions (Ivancic et al., 2017). Entering new markets through acquisition has presented acquiring firms with significant problems; however, that has had a negative impact and caused the acquisitions to not live up to the expectations of the acquiring firms (Zakaria et al., 2017). King et al. (2020) explained that failures in the integration process are partly to blame, which can contribute to fear of job loss, a higher perception of unfairness, and an increased amount of employee stress and uncertainty. Another significant problem is employee resistance which can cause decreased productivity, decreases in morale, and issues with turnover (Charoensukmongkol, 2016). These issues have been well-researched; however, there is a lack of literature on the phenomenon within the music publishing industry in Nashville where acquisitions are on the rise (Towse, 2017).

In recent years, new technologies have transformed how music is consumed by the public (Towse, 2017). Consumption through digital streaming has grown exponentially. In 2015, streaming became the largest source of annual music industry revenues as well as the primary method that the public utilizes to listen to their favorite song or artist (Datta et al., 2018). Large multinational publishing firms have realized the need to adapt their business models to account for the income shift to streaming which has resulted in acquisition strategies to increase market share (Towse, 2017). There is not any prevalent literature on how publishers and songwriters within the Nashville music business cluster are affected by the recent rise in acquisitions.

Nashville Market

The music business alone contributed over five billion dollars annually to the Nashville local economy (Baker, 2016). Raines and Brown (2007) contended that the music business is a significant factor in the city’s prosperity and future growth. The market consists of over 130 music publishing companies that make up the largest publishing center in the southeastern portion of the United States (Baker, 2016). The majority of the publishing industry has traditionally been located in an area called music row. The area is approximately a mile long located along 16th and 17th avenues and was designated in 2015 as a national treasure by the National Historic Trust for Preservation (Fuston, 2015). More than 56,000 jobs are sustained by the local music industry (Baker, 2016). Lingo (2020) discussed the autonomy that many workers enjoy within the industry which has led to an entrepreneurial spirit within the community. In recent years, record labels have been focused more on adapting to the digital marketplace than on developing recording artists. The shift of resource allocation has presented a situation when record labels are turning to entrepreneurs like small publishing houses for talent cultivation. This change has bolstered the spirit of cooperation within the local market that Baker (2016) described as a creative business cluster. The phenomenon that Romanova et al. (2019) explained of workers and businesses within a creative cluster enjoying a mutually beneficial relationship with one another is evident in the Nashville publishing community.

Creative Business Clusters

Geographical areas where businesses in a particular industry will cluster together to benefit from the local market are called business clusters (Park et al., 2019). The companies within a business cluster are usually interconnected within a particular field (Zhou et al., 2020). Nashville, otherwise known as “music city”, is one such area where record labels, music publishers, and all facets of the music industry work together in a symbiotic fashion to ultimately promote the genre of country music. The various music business entities cluster together in Nashville to take advantage of the proximity to major labels in the same way actors and screenwriters move to Hollywood to be close to the film industry (Baker, 2016). Clustering can help create competitive advantages for all entities within the cluster as well as an entire industry (Romanova et al., 2019). Cottineau and Arcaute (2020) explained, however, that when large organizations attempt to enter a market and take advantage of a cluster, the entry may jeopardize the benefits of the clustering for smaller organizations.

Study Design and Method

A flexible design and a qualitative method were chosen for this case study. A flexible design was chosen because unexpected conclusions were anticipated in the examination of Nashville music publishers within the local creative business cluster, who have had their firm purchased by an international organization. Robson and McCartan (2016) recommended a flexible design for studies that might have to adapt as research evolves. Creswell and Poth (2018) also suggested the use of qualitative research methods when seeking to make sense of a phenomenon or interpret what happens naturally in the world. Case study was chosen as the design style because Yin (2018) explained that case studies are utilized when a researcher attempts to study a phenomenon within the bounds of a real-life, contemporary context, or setting. Case studies use multiple sources of evidence to empirically investigate events within their real-life context (Robson & McCartan, 2016). It was anticipated by the researcher that in this case study, issues common to international acquisitions would occur, such as resistance to change, feelings of job insecurity, and lack of, or no, integration strategy (Bansal & King, 2020; Probst et al., 2007; Kets de Vries, 2015). It was also expected that issues unique to the Nashville market would also arise that might present the need for a flexible design.

Participants

This study focused on the international acquisition and integration of Nashville music publishing companies. Participants from multiple companies and job types were necessary to adequately examine the issue. Nashville, Tennessee was the research location. The culture of an acquired firm might not always be amenable to the culture that an acquiring firm desires; therefore, it was important to examine the culture of the market’s business community within and between firms (Geringer et al., 2016). Nashville’s culture and symbiotic nature, due to the market being a creative business cluster, may give acquired workers a unique understanding of being acquired by an international firm. The sample population for this study focused on individuals within small publishing companies that had been acquired and integrated into a large international firm. Participants ranged from creatives to general managers. The facts associated with the process were then triangulated through the different accounts. Issues unique to the Nashville market were uncovered through individual perspectives. Participants were interviewed with questions that were open-ended, which allowed them to tell their own experience of their firm being acquired and integrated. Participants were interviewed virtually in a secure format over the Zoom platform due to the Covid 19 pandemic. In order to preserve participants’ rights and data integrity, each interview was confidential and participant information will not be made public. The recordings and transcripts will be held in a secure location and will be destroyed three years after the study’s release. Each participant and their responses were given an identifiable and unique code.

Population and Sampling

It is not realistic or possible to recruit an entire population of interest for a study (Knechel, 2019). Only a sample is chosen to represent the broader population’s characteristics. The number of recent acquisitions within the Nashville market makes it difficult to interview all who have experienced their firm being acquired by an international firm. For this study, 16 participants were chosen. The intent was to interview participants until data saturation was reached and the responses gleaned no new knowledge about the experience. Each participant needed to have worked for a small local Nashville publishing company that had been acquired and integrated into a multinational firm. The criteria for participants also required each to have worked for the small local organization before and after acquisition and integration by an international firm. Systematic sampling was chosen for this study which considered the eligible population list and determined specific participants who might best represent the phenomenon under study (Knechel, 2019; Robson & McCarten, 2016). The sample was then handpicked.

Data Collection

Data collection was in the form of one-on-one interviews for this study. The sample size was 16 participants. All participants had worked for a small publishing company in Nashville that had been acquired and integrated into an international firm. Open-ended questions were utilized for the interviews to give the participants the opportunity to give historical information on the experience. Open exchanges were encouraged which included follow-up questions. Qualitative research is sometimes questioned for its rigor; therefore, data collection needed to be thorough until saturation was reached (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Each interview was recorded and coded to pinpoint integral portions of information. The data management software, NVivo, was used in the coding and analysis of the data. Coding can help organize the lengthy data obtained from interviews and aid in finding common themes (Alam, 2020). The researcher was the primary instrument of data collection through the interviews (Rimando et al., 2015). An interview guide, shown in Appendix A, was a secondary instrument of data collection. As Kallio et al. (2016) suggested, the interview guide was not followed too strictly to provide an opportunity for participants to provide their own thoughts on the experience and allow the study to adapt if necessary.

The first interview questions, in part A of the interview guide, allowed participants to provide a brief history of their own careers and their role in the organization that was acquired. This helped to set the stage for the interview and show the credibility of each participant. The follow-up questions in part A had the participants describe how or if their role changed after integration into the international firm. Part B of the interview guide explored the issues pertaining to the factors that increased or decreased the participant’s job satisfaction and productivity. Participants were asked to describe the experience of their company being acquired and integrated and the follow-up questions asked them to describe how the experience affected their job satisfaction and productivity. Question set C allowed the participants to describe their experience since acquisition and integration had taken place. The follow-up questions asked participants to address the factors that contributed to the loss of productivity or job satisfaction.

Question set D delved further into the experience of each participant by asking what strategies that acquiring firms utilized during the acquisition and integration process to help combat problems that may arise with productivity and job satisfaction. The follow-up questions asked what types of strategies were used and if they were successful. The final question sets E and F explored the culture of the Nashville music market and the culture of the acquiring firm. Question set E asked participants to describe the culture of their original organization pre-acquisition. Follow-up questions asked participants to compare their previous organization’s culture with the acquiring international firm. Question set F pertained specifically to the Nashville music business cluster. Participants were asked if the Nashville creative cluster’s culture was unique in any way. Follow-up questions asked if the acquiring firm took the local culture into account throughout the acquisition and integration process and if the company’s approach had a positive or negative effect on productivity or job satisfaction.

Limitations

It is important to always consider the potential weaknesses or limitations of research (Keightley et al., 2012). While the number of Nashville small publishers that have been acquired by international firms is numerous and increasing, finding participants willing to discuss that experience was an expected challenge. The assumption was that workers may be reluctant to discuss their experience due to the fear of repercussions. Many possible participants might still be employed by the acquiring firm. Participants were assured the interviews would be confidential and that no names will be used to mitigate the expected issue. Participants were required to complete a consent form explaining the purpose of the study. The consent form, shown in Appendix B, disclosed any risks relating to the study while assuring each participant’s confidentiality. The researcher also expected a challenge in finding enough participants from different firms. Too many participants from any one firm could skew the data. To mitigate the issue, participants were chosen carefully from multiple job types with firms as well as different firms to ensure that responses were diverse. Researcher bias was also an initial concern. The researcher has worked in the Nashville music industry for almost 30 years and bias toward the topic may have been present. To account for the possibility of researcher bias, the researcher bracketed out and separated his own bias and focused only on the participants’ accounts.

Results

Nashville’s Family-style Business Culture

The most dominant theme contributing to integration resistance that was uncovered from the participant interviews was that of the family-style of business culture of Nashville’s music publishing market. Baker’s (2016) description of Nashville as a creative cluster was solidified from the participant’s accounts. The accounts also described the mutually beneficial relationship shown in the music creative cluster similar to what Romanova et al. (2019) suggested. Many small independent firms make up the local Nashville industry. Participant three explained that the culture of his small independent firm was “very small and close” (personal communication, March 21, 2021). Participant one (personal communication, March 21, 2021) described Nashville’s music publishing market as “a real handshake business”. Participant four called the market an “intimate and close community” and described managers as being very close to their teams and treating them “like family” (personal communication, March 24, 2021). According to participant six, Nashville is the type of place where you can leave your keys in your car in the driveway (personal communication, March 30, 2021). Multiple participants explained that information travels quickly in Nashville’s close-knit culture. If you do not treat someone well, it will be known all over town by lunchtime that same day (Participant 10, personal communication, April 15, 2021). Participant four further explained that his boss, at his international firm, expressed frustration about Nashville by saying, “you can think something in LA and hear it in Nashville” (personal communication, March 24, 2021). The majority of participants described Nashville as a very relationship-based industry.

Of the participants in the study, participant 12 provided a valuable perspective. The participant is the local CEO of one of the market’s international publishing companies. He explained that Nashville’s publishing industry conducts business unique to the rest of the world (Participant 12, personal communication, April 19, 2021). He outlined that the Nashville publishing market is built on finding undeveloped talent and then developing that talent until either failure or success is achieved. Publishers will champion their creatives and focus on serving and cultivating their talent. In most other music markets around the world, the publishing side of the business is more transactional and less relational (Participant 12, personal communication, April 19, 2021). The development side of working with creatives is either minimal or not present at all in other music markets. Participant 12 also described the long-term view of working with creatives and the service element that is present within the Nashville market’s small publishing companies. It is much less expensive for small companies to sign and develop new talent than to try and pay talent that is already successful. This development in conjunction with service and cultivation is what helps to create the extremely tight-knit family culture within firms.

Most participants described the Nashville music publishing market as competing firms within the same field working together for mutual benefit as Park et al. (2019) and Zhou et al., (2020) described as a characteristic displayed by creative clusters. This cooperation can occur when one company’s creative songwriter composes songs with writers from other companies. In many cases, the separate firms work together to exploit and market the co-owned creative works. According to Participant one, this culture is often overlooked when an international firm acquires and integrates a small Nashville music publisher (personal communication, March 21, 2021). In his case, no concern was paid to the Nashville culture. Workers were expected to adapt to the international culture. Instead of the cooperative and cultivating aspects of the small firms, workers were expected to keep secrets and keep things in-house as much as possible. The days of working with other firms for mutual benefit were over. The participants overwhelmingly described the international firms as either not comprehending or caring about the unique culture of the Nashville market. Participant two further explained that local politics were not considered and the international firm tried to buy their way into the market, which rubbed people the wrong way.

Cooperation and Camaraderie

Numerous participants described the culture of Nashville’s music publishing market as having camaraderie. Camaraderie could be described as a sense of belonging, solidarity, being a part of something bigger than yourself, or an obligation to others (Filo et al., 2009). Ramsey et al. (2021) described camaraderie within a market and organizations as interpersonal relationships where individuals share a bond due to similar experiences and perceptions about the market or organization’s climate. This camaraderie is evident in participant two’s description of workers in the market pulling for each other even though they are competitors (personal communication, March 23, 2021). He explained that it is common for competing companies’ workers to hang out together at restaurants and bars during and after work hours. Competing publishers have mutual respect for each other, which participant 13 outlined as because they are “all up against the same thing” (personal communication, April 21, 2021).

Nashville music publishing market camaraderie is not only displayed between companies but the word camaraderie was also used to describe the culture within the walls of the market’s publishing companies as well. Participant 11 described his small company, pre-acquisition, as one where everyone cared about each other’s personal lives and their career success (personal communication, April 15, 2021). Co-workers know what each other are going through and generally care and emphasize with each other (Participant 13, personal communication, April 21, 2021). There is very little jealousy displayed within a company’s walls. When a songwriter obtains a cut or a single, the writer’s coworkers are happy and proud of their peer’s success. Co-workers cheer each other on because if one person within the firm is having success, it can open doors to opportunities or success for all within that company. Participant nine explained that the camaraderie within and between publishing companies is a “real Nashville thing because it’s the South” (personal communication, April 13, 2021).

Small House Environment

The Nashville music publishing community has traditionally been based on 16th and 17th avenues in Nashville. Multiple participants fondly recalled small publishing companies lining those streets in small mid-century homes converted into business offices. Participant nine called the small Nashville publishers “boutique mom-and-pops” (personal communication, April 13, 2021). The in-house camaraderie mentioned in the previous section was evident in the small house environment. Managers tend to be hands-on and very involved in developing their staff. Managers are also very accessible. Participant ten recalled spending each morning in the office of his boss strategizing about his career (personal communication, April 15, 2021). He described his boss as his cheerleader. Participant 13 explained that small publishers in Nashville are decent people and treat their songwriters and employees with respect (personal communication, April 21, 2021). Songwriters working for small publishers feel as if they are surrounded by people that care, that are willing to invest in their careers, and are pulling in the same direction (Participant 15, personal communication, April 28, 2021).

International Firms

The results of the study showed that international acquiring firms care less about nurturing, cultivating, and serving their creative staff and more about the bottom line and making immediate profit. Participant two explained that in his case, the international publisher did not comprehend how the Nashville industry conducts business as opposed to other publishing markets (personal communication, March 23, 2021). Additionally, the camaraderie shown in smaller local publishing companies was not present, and the internal culture of the international publisher was described as “me, myself, and I” (participant two, personal communication, March 23, 2021). The lack of understanding and consideration of the local publishing market is why participant two ultimately decided to leave the international publishing company post-integration. He felt that the management of the international company and their practices would hurt his career due to rubbing others in the market the wrong way. Some participants explained that the day-to-day culture of the international publishing company was very rigid. Participant five explained that the speculative nature of small Nashville publishers was lost and the international firms only signed songwriters that already had activity or significant careers (personal communication, March 29, 2021). It was out of the question to sign a songwriter that needed to be developed over time. Participant six further explained that international publishing companies had little concern for the local market’s practices and culture and that only financial concerns were addressed (personal communication, Mach 30, 2021).

Multiple participants discussed the impersonal nature of the international acquiring firms. Participant nine explained that the culture of workers socializing, working together for mutual benefit, and caring for each other was not present and that it was more of a formula that had to be followed (personal communication April 13, 2021). A number of participants described the international publishing companies and their offices as sterile and explained that workers did not have access to management or co-workers. In one case, administrative and management staff were separated in different parts of the building where each needed special identification cards to access (Participant 16, personal communication, April 29, 2021). There was no casual hanging out around a coffee pot that is typical at traditional small Nashville publishing firms. To sum up, participant ten explained that his international publishing company had no personal aspect (personal communication, April 15, 2021). He felt that the international firm’s managers were ruthless in business. Instead of working with people in Nashville, he thought they were more interested in owning and dominating the town.

Outlier

As the new information gleaned from each participant’s account became almost non-apparent, one participant proved to be a significant outlier. All other participants had described declines in job satisfaction due to the loss of the small company environment, the camaraderie of the small firm, and the cultivation that small firms provide. Participant 12 had managed his own small Nashville publishing company for many years and had been extremely successful. That success is what lured the major international publisher to acquire his firm. Participant 12 was asked to be the head of the international publisher’s local office, which created a unique perspective for this study. His boss recognized not only the successful publishing company he had managed but also the successful culture of his past company. He was asked to bring his small publishing company’s culture to the international firm. He was able to manage the multinational’s local operations in the same way he had his previous company, just on a larger scale. This autonomy, along with the higher salary and the prestige of the international firm, only increased his job satisfaction. Participant 12 explained that his employees that made the transition were also encouraged to operate in the same manner as they did in the old firm, which helped to eliminate any decline in job satisfaction (personal communication, April 19, 2021). Participant 12 was able to accomplish and obtain the benefits from what King et al. (2018) described as bringing the small company feel to an international firm.

Data Visualization

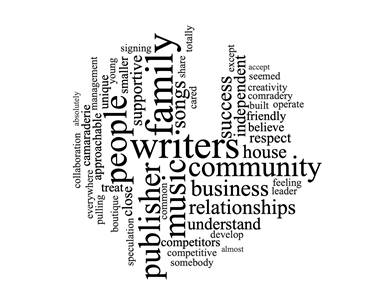

A common argument used against the validity of qualitative research is in the visualization of a researcher’s data (Pokorny et al., 2018). Researchers must find ways to display the data collected into some type of visual representation. Yin (2018) suggested using graphics, such as flow charts and graphs to aid in the visualization of data. For this study, the computer software NVivo was used to create word clouds representing the participants’ descriptions of the traditional Nashville small publisher and the international firms that have entered the market through acquisition. The first word cloud, shown in figure one, displays the frequency of keywords used by participants to describe the environment and culture of their original small Nashville firm. The words that were mentioned more frequently appear larger within the word cloud. Displayed are the abundant mentions of community, family, camaraderie, relationships, supportive, friendly, believe, close, and respect. All show what Romanova et al. (2019) described as the mutually beneficial relationship shown in creative clusters.

Figure 1. Word cloud of Nashville publisher characteristics

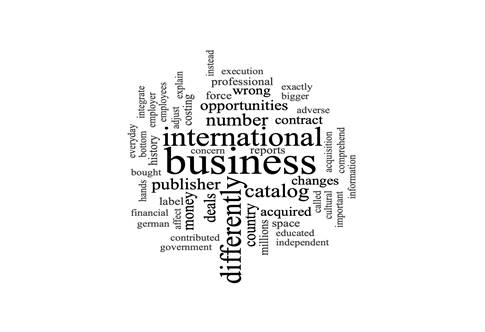

Figure two, below, shows a word cloud for the participants’ descriptions of the culture of the international firms that acquired their previous organization. The words displayed more frequently to describe international firms were number, opportunities, money, changes, financial, adverse, and business. Participants described the international firm’s culture as affecting them adversely. Most mentioned changes in how the firm operated that went against how their previous firm conducted business. Multiple participants explained that operations were merely financially focused and that the relationship aspect of the small local Nashville firm was lost in the international firm.

Figure 2. Word cloud of international publisher characteristics

Conclusions

The study of integration resistance throughout the process of international acquisition and integration within the Nashville music publishing creative cluster uncovered valuable cultural implications for firms to consider when acquiring firms within the market. Three main themes were apparent that were discovered by close examination of the accounts of 16 participants. Each participant was interviewed about the experience of their small Nashville music publishing company being acquired by a large multinational firm. The most dominant theme in the participant’s accounts was the family-style culture that firms and workers embody in the Nashville publishing market. It is a market where most participants personally know each other and tend to socialize together and celebrate each other’s achievements, even if they are with a competing firm. The second predominant theme was that of the camaraderie that firms and workers display. Competing publishers and songwriters work together in a symbiotic fashion for mutual benefit. Workers are more than competitors, but view a competing firm’s workers as friends and colleagues. The third theme woven throughout each participant’s account is the preference for locating the business in a small house environment that so many Nashville workers are accustomed. International publishers tended to have larger more sterile office-type environments instead of the family-style environment of being located in a house. The small house environment bolstered creativity in the participant’s minds. Participant 12, the outlier, found success and set a strong example of bringing the small family environment of cultivation, service, and camaraderie which proved successful in having satisfied workers post-acquisition and integration.

Recommendations

The results from this study showed that a strategy for acquisition and integration within the Nashville music publishing market must include consideration of the creative business cluster’s culture. In all but participant 12’s account, international publishers entering the Nashville market through acquisition have not utilized strategies to incorporate the local market’s culture post-acquisition and have expected firms to adapt to the overall culture of the acquiring firm. Acquiring firms should consider the family-style environment of the market during integration. International firm managers should also seek to cooperate with other firms within the market and focus on serving and cultivating their staff. When possible, firms should also attempt to either house their operations within the small boutique homes the workers are accustomed to or find ways to bring the family-style culture to the corporate office. Koles and Kondath (2014) and Kets de Vries (2015) both recommended participative strategies during integration to help acquired managers and employees feel like they have a part in the company’s direction. Participant 12’s example also serves to outline the importance of bringing management from the acquired firm into the organization so leaders have an understanding of the local market. Organizations that approach acquisition within the Nashville publishing market by taking into account the creative cluster’s traditional culture and practices will have a better chance of success.

Future Research

The results from the study uncovered some areas where further study is recommended. The changes being experienced in Nashville’s music publishing culture due to increased international acquisitions and the influence of the culture of international firms have not been examined. It was noted by participant six that it has become difficult to work in small boutique houses due to the size of the international firms that are moving into the market. Many companies have moved away from 16th and 17th avenues to more inexpensive parts of Nashville. The result of such moves has created a phenomenon where many of the owners of the small homes are selling to developers and high-rise condos or office complexes are quickly replacing the homes. The larger international firms are choosing to locate their operations in the new office buildings either on Music Row or downtown away from the traditional location of the music industry. It is important to examine if what Cottineau and Arcaute (2020) explained is happening where when large firms enter a cluster, it may jeopardize the benefits of the cluster. Denney et al. (2020) found that business clusters have a life-cycle that includes formation, decline, or evolution. Further study on the Nashville creative business cluster should focus on what part of the life cycle the business cluster is currently experiencing.

Appendix B: Research Participant Consent Form

References

Alam, M. K. (2020), A systematic qualitative case study: Questions, data collection, NVivo analysis and saturation, Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-09-2019-1825

Baker, A. J. (2016). Music scenes and self branding (Nashville and Austin). Journal of Popular Music Studies, 28(3), 334-355. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpms.12178

Bansal, A. & King, D. R. (2020). Communicating change following an acquisition. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1803947

Charoensukmongkol, P. (2016). The role of mindfulness on employee psychological reactions to mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 29(5), 816-831. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-05-2015-0068

Chelsey, C. G. (2020). Merging cultures: Organizational culture and leadership in a health system merger. Journal of Healthcare Management, 65(2), 135-150. https://journals.lww.com/jhmonline/Abstract/2020/04000/Merging_Cultures__Organizational_Culture_and.11.aspx

Cottineau, C. & Arcaute, E. (2020). The nested structure of urban business clusters. Applied Network Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-019-0246-9

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. (4th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Datta, H., Knox, G. & Bronnenberg, B. J. (2018). Changing their tune: How consumers’ adoption of online streaming affects music consumption and discovery. Marketing Science, 37(1), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2017.1051

Denney, S., Southin, T., & Wolfe, D. A. (2020). Entrepreneurs and cluster evolution: The transformation of Toronto’s ICT cluster. Regional Studies, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1762854

Filo, K., Funk, D., & O’Brien, D. (2009). The meaning behind attachment: Exploring camaraderie, cause, and competency at a charity sport event. Journal of Sport Management, 23(3), 361-387. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.3.361

Fuston, L. (2015). Nashville’s music row named a national treasure. Pro Sound News, 37(2). https://www.mixonline.com/recording/music-row-named-a-national-treasure

Geringer, J. M., McNett, J. M., Minor, M. S., & Ball, D. A. (2016). International business. McGraw-Hill Education.

Ivancic, V., Mencer, I., Jelenc, L., & Dulcic, Z. (2017). Strategy implementation: External environment alignment. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 22, 51. https://hrcak.srce.hr/190505

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A., Johnson, M., & Docent, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi‐structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12). https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031

Keightley, E., Pickering, M., & Allett, N. (2012). The self-interview: A new method in social science research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.632155

Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2015). Vision without action is a hallucination: Group coaching and strategy implementation. Organizational Dynamics, 44(1), 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2439749

King, S., Hopkins, M., & Cornish, N. (2018). Can models of organizational change help to understand ‘success’ and ‘failure’ in community sentences? Applying Kotter’s model of organizational change to an integrated offender management case study. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 18(3), 273-290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817721274

Knechel, N. (2019). What’s in a sample? Why selecting the right research participants matters. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 45(3), 332-334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2019.01.020

Koles, B., & Kondath, B. (2014). Strategy development processes in Central and Eastern Europe: A cross-regional perspective. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 9(3), 386-399. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-08-2012-0092

Lingo, E. L. (2020). Entrepreneurial leadership as creative brokering: The process and practice of co-creating and advancing opportunity. Journal of Management Studies, 57(5), 962-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12573

Park, J., Wood, I. B., Jing, E., Nematzadeh, A., Ghosh, S., Conover, M. D., & Yong-Yeol Ahn. (2019). Global labor flow network reveals the hierarchical organization and dynamics of geo-industrial clusters. Nature Communications, 10, 1-10. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-11380-w

Probst, T. M., Stewart, S. M., Gruys, M. L., & Tierney, B. W. (2007). Productivity, counterproductivity, and creativity: The ups and downs of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 80(3). 479-497. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317906X159103

Pokorny, J. J., Zanesco, A. P., Sahdra, B. K., Norman, A., Bauer-Wu, S., & Saron, C. D. (2018). Network analysis for the visualization and analysis of qualitative data. American Psychological Association. 23(1), 169-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/met0000129

Pollack, J. (2015). City Spotlight: Nashville behind the music: Booming marketing region is about more than ‘big hair, belt buckels and boots’. Advertising Age, 86(19). 40-41. https://adage.com/node/1093766/printable/print

Raines, P. & Brown, L. (2007). Evaluating the economic impact of the music industry of the Nashville, Tennessee metropolitan statistical area. MEIEA Journal 7(1). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A234791354/AONE?u=tel_oweb&sid=googleScholar&xid=e5dc7eb0

Ramsey, J. R., Lorenz, M. P., Liu, J. T., Posthuma, R. A., & Gonzalez-Brambila, C. N. (2021). Exploring perceived innovativeness in Central America and the Caribbean: Cross-level interactions of perceived camaraderie, organizational camaraderie climate, and organizational gender diversity. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, https://doi-org.ezproxy.liberty.edu/10.1080/09585192.2021.1893786

Rimando, M., Brace, A., Namageyo-Funa, A., Parr, T., Sealy, D., Davis, T., Martinez, L., & Christiana, R. (2015). Data collection challenges and recommendations for early career researchers. The Qualitative Report, 20(12). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol20/iss12/8/

Robson, C., & McCartan, K. (2016). Real world research. (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Romanova, A., Abdurakhamanov, A., Ilyn, V., Vygnanova, M. & Skrebutene, E. (2019). Formation of a regional industrial cluster on the basis of coordination of business entities’ interests. Procedia Computer Science, 149. 525-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.01.171

Towse, R. (2017). Economics of music publishing: Copyright and the market. Journal of Cultural Economics, 41(4), 403-420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-016-9268-7

Upadhyay, P. & Kumar, A. (2020). The intermediating role of organizational culture and internal analytical knowledge between the capability of big data analytics and a firm’s performance. International Journal of Information Management, 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102100

Yin, R. K., (2018). Case study research and applications. (6th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Zakaria, R., Fernandez, W. D., & Schneper, W. D. (2017). Resource availability, international acquisition experience, and cross-border M&A target search: A behavioral approach. Multinational Business Review, 25(3), 185-205. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBR-03-2017-0016

Zhou, Y, Li, Y., & Deng, F. (2020). Network proximity and communities in innovation clusters across knowledge, business, and geography: Evidence from China. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9274407