I am as weary as the next man of fanciful descriptions of computational miracles. They are too often written by innocents who have been seduced by the idea of the computer without ever having had intimate contact with the monstrous machine itself nor the passionate desire to dynamite it to bits in frustration at its recalcitrance. What I am about to describe is no pipe dream. It is a realistic, three-year old project that is presently under way at an American university. To bring it to fruition will require continuing national and international cooperation, three further years of research and development, and a lot of money.

Specifically, music has the unique opportunity at the present time to lead all of the arts and humanities into the world of computerized communication. In this new world, complete information about all significant humanistic literature will be speedily accessible to scholars, teachers and students; and authors and editors will be able to prepare elegant-looking books and periodicals right in their own offices—with a single keyboarding and without need for outside typesetting or repeated copy-galley-page proofreading.

It is appropriate here to acknowledge the truism that information does not constitute knowledge and that ready access to all the world's information and immediate communication of all new research will not of themselves create knowledge. However, if these developments could drastically reduce the scholar's search time and forestall duplication of effort, would they not provide him with greater opportunity for contemplative thought, for the testing of hypotheses, for creative research, and thus for the expansion of knowledge?

The ACLS/CUNY Project

The opportunity for music lies in the American Council of Learned Societies-City University of New York project for the development of an overall automated information system for scholars and scholarly organizations in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. To quote from an as yet unpublished ACLS report:

As a result of experience gained in the past three years from pilot projects and educational efforts, and in international planning and organization, the ACLS is anxious to press forward toward its goal of revolutionizing, through the application of computer technology, the bibliographical control and information systems of scholars engaged in research in the humanities and social sciences. Enough has been learned since we began in 1966 to suggest that a continued intensive effort over the next three years, properly supported, will bring us within sight of such a goal. The result will be the availability of an integrated, automated system that will provide the various scholarly disciplines with complete up-to-date bibliographic services while at the same time enhancing access to data across disciplinary lines.

The ACLS is now joining forces with the Graduate Center of the City University of New York in the second phase of the project which will go beyond the establishment of traditional abstracting and indexing services in the humanities, resembling those long available in the physical sciences. It will develop advanced retrieval, index generation, editing and photocomposition techniques, specifically designed to deal with humanistic (rather than scientific or technical) literature. It will seek to avoid the widespread duplication of effort that has plagued the scientific world, and at the same time to take full advantage of the advances already made in the flow and transfer of scientific information.1 By its new methods, it hopes to enable the university presses of this country to publish the fruits of academic scholarship more readily and completely than has thus far been economically possible.

In 1966, the ACLS designated a newly established music literature venture, RILM (Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale), as the pilot project through which its overall plan was to be developed and tested. RILM, as most of you know, has its International Center at Queens College of the City University of New York. It is the first project of its kind in the humanities and was established by the International Musicological Society and the International Association of Music Libraries to attempt to deal with the explosion in musicological documentation by means of international cooperation and modern technology. RILM is concerned with the whole of musicology in its broadest definition, including all of its branches and related disciplines. It is governed by a Commission International Mixte designated by the two founding societies. In the United States, RILM is sponsored by the American Musicological Society, the Music Library Association, the Society for Ethnomusicology, and the College Music Society. RILM will eventually be concerned with retrospective materials, but is presently concentrating on current literature only.

RILM abstracts, the official journal of RILM, publishes abstracts indexed by computer of all significant literature in music that has appeared since 1 January 1967. It appears four times a year, the fourth issue being a cumulative index. Included are abstracts of books, articles, essays, reviews, dissertations, catalogues, iconographies, etc. Thus far, the 4 issues of Volume I (1967) with 2532 abstracts, and the 1st issue of Volume II (1968) with 1433 abstracts, have appeared.

The RILM System

The overall ACLS/CUNY project may best be understood through a step-by-step description of how the RILM system will function when all of its six phases are operational. The system, about one-third developed thus far, is being designed so that it will be usable by all scholarly disciplines, individually or in concert, and on various makes of computers and photocomposition devices. It will be capable of producing a scholarly journal, such as College Music Symposium from start to finish, or specialized bibliographies from stored data, or RILM abstracts. The six phases are as follows: 1. data collection 2. processing and editing 3. keyboarding (tags and codes) 4. computer operations 5. photocomposition 6. automatic byproducts (cumulative indices, specialized bibliographies, information retrieval, interdisciplinary search, document retrieval).

Phase I: Data collection

The RILM system is based on author cooperation in the preparation of abstracts. This practice, long established and accepted in the physical sciences, is becoming a necessity in the humanities.2 The vehicle for data collection is the preprinted abstract form which, when properly filled out, provides an accurate bibliographic citation as well as an informative abstract of the work's contents. The author sends his completed abstract form to one of several persons. (See illustration no. 1).

ILLUSTRATION I

The RILM System. Phase I: DATA COLLECTION

If the work is an article in a fully abstracted "core" music journal, Festschrift or congress report, the editor of the collective volume is usually in charge of gathering the abstracts for the articles and citations for the reviews contained therein and sending them, along with a copy of the publication, to the national RILM committee of his country. For those music periodicals which are not designated as core journals, the chairman of the national committee will request abstracts of the authors of those articles deemed relevant to RILM. For books, the author may send the abstract directly to his national committee chairman or first to his publisher who will send it to the committee together with a copy of the volume. If the work is a doctoral dissertation or a master's thesis, the departmental chairman or graduate advisor will usually receive and check the completed form and then send it on to the national committee. National committees have been established in over forty participating countries. Some are based in national libraries, others at musicological institutes of universities, etc. The US national committee has its home in a crowded corner of the International Center. An essential and sometimes delicate task of the national committees is to reject those abstracts which do not conform to inclusion principles established at the Salzburg and Ljubljana meetings of the IAML and the IMS.3

Having checked the abstracts for completeness and accuracy, the national committee chairman will forward them to the International Center in New York, together with copies of the publications themselves whenever possible. This is an essential and frequently neglected component in the process. When an article or book is not at hand, the International Center editors too often find themselves unable to check bibliographical details or even common spelling errors; more important, they may be hampered in the preparation of the in-depth index for which the abstract alone may be insufficient.

In addition to the national committees, the International Center receives abstracts from another source: area editors. At the present time, some twenty experts in specialized areas of music or closely related disciplines work with the RILM project on a volunteer basis. It is the function of an area editor to survey systematically, the literature and bibliographic tools of his specialty. When he encounters an article, book, or dissertation relevant to the RILM project, he either requests an abstract of the author or writes it himself. In this way, literature in specialized areas such as music therapy, acoustics, or psychology and hearing, as well as in related disciplines such as dance, sociology, or archeology, is reported. Finally, the International Center maintains exchange agreements with other abstracting and bibliographic services, e.g., International Medieval Bibliography, Sociological Abstracts, and Psychological Abstracts, permitting valuable data collection through secondary sources.

Phase II: Processing and Editing

From the moment an abstract form enters the International Center until it is safely committed to storage within the computer, it bears an accession number by which it may be identified and located and by which a running count of abstracts received for any issue is maintained. An index card with basic bibliographic data is prepared for the master control catalogue to check for duplication. Abstracts in exotic foreign languages are xeroxed and sent out for translation (a copy of every abstract remains on file at all times). Abstract forms are printed in 3 languages—and colors (English, yellow; French, pink; German, blue)—but abstracts are received in many tongues, including Finnish, Russian, Greek and Esperanto. All abstracts are checked for missing data and, if necessary, set aside until completed. If the item is from a core journal or a Festschrift, it is necessary to see that all other articles and reviews in the volume are included in the same RILM issue. When suitably numbered, indexed, checked, and translated, the abstract is ready for editing.

The editors receiving the processed abstract forms have a three-fold job: copy editing, classifying, and indexing. They must make sure that the abstract conveys an informative and objective portrait of the contents of the article or book, that it wastes no words nor repeats what has been said in the title, and that it is written in clear, literate English. They classify the item by assigning it both a RILM classification number, e.g., 26 (Classic), 45 (Wind instruments), 72 (Pedagogy: colleges and universities), and a descriptive pair of letters indicating type (article, book, commentary, dissertation, or review) and source (periodical, Festschrift, congress report), e.g., ap (article in a periodical), bm (book or monograph), rf (review of a facsimile). The editors initiate the indexing process by marking all appropriate names and places to be listed, and by choosing subject terms from the existing thesaurus of RILM subject headings. New subject headings may also be listed and automatically become part of the "open-ended" thesaurus. The editors ignore names of authors, editors, compilers and translators appearing in the citations, for such names are automatically retrieved by the computer. The list of subject names, places and terms (or keywords) is later permuted with the aid of a partially automated system of faceted indexing which makes maximum use of the computer without surrendering intellectual control. The initial indexing is crucial to the entire project because it will be used for a variety of printed index cumulations as well as for responses to individual retrieval requests.

Phase III: Keyboarding

This phase is in a sense equivalent to conventional typesetting. The essential difference lies in the simultaneous production of a machine readable record. Keyboarding may be accomplished in the editor's own office and requires only the services of a good typist or "keyboarder," plus an inexpensive "offline" keyboarding device, such as an offline teletype, a perforated-papertape machine, or a keypunch for punchcards. Costly computer time need not be used at all at this stage. (RILM will be experimenting with several different inputting devices including online time-shared terminals that display the typed data on a video screen as well as on paper).

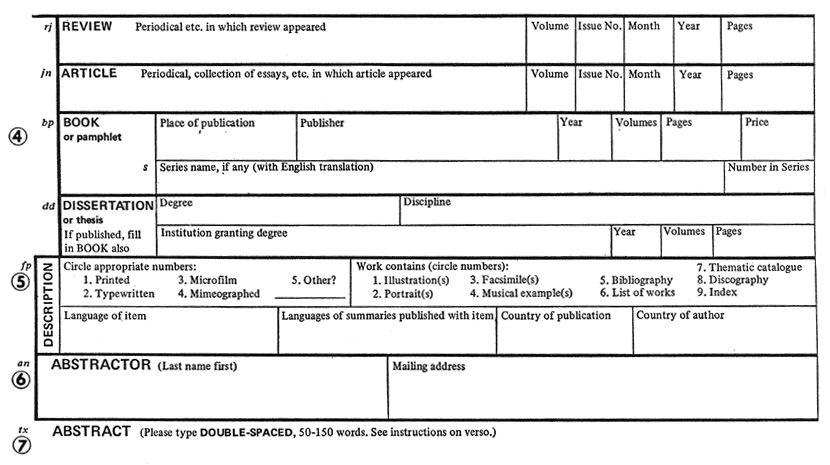

The typist works directly from the edited abstract form, adding the "tags" that are pre-printed in small letters on the abstract form itself. (See illustration no. 2.)

ILLUSTRATION II

Portion of RILM abstract form

These tags and the several sub-elements following each of them identify a specific segment of information for future retrieval. The same tags will also serve to specify format and type fonts, to insert desired punctuation, and to call forth expansions of keyboarded abbreviations. Proper tagging results in great economy of keystrokes and reduction of errors.4 Tags are announced to the machine by asterisks. The keyboarder must start with the identification tag: *id, but then may type the others in any order; sub-elements are separated by slashes. The following, fictitious item, for example, uses 6 tags: *id (identification number), *cr (cross reference), *t (title), *a (author), *jn (journal), *fp (features of the publication), *tx (text of the abstract).

*id 69/ /A123/ap/26 *cr 45 *t Mozart und die Flöte/Mozart and the Flute *a Shlepperman, Harry/U. of Mush/Lux *jn JbMf/III/4/Sept/69/33-63 *fp 4/24589/De/EnFr *tx (50-100 word abstract, not given here)

As will be seen in phases IV and V, the computer can automatically rearrange and expand this citation and print it by photocomposition in any desired type font and type size, expanding abbreviations, if desired, from its pre-stored "dictionaries." The above example could be printed out in the appropriate section of the journal, 26 (Classic) as follows:

69369 ap26

SHLEPPERMAN, Harry (University of Mush, Luxembourg). Mozart und die Flöte [Mozart and the flute], Jahrbuch für Musikforschung III/3 (September 1969) 33-63. Port., music, bibliog., them.cat., discog. In German; summaries in English and French. (Abstract follows, not given here).

In addition, because of the tag *cr 45, an author and title citation would also automatically be printed as a cross reference in section 45 (Woodwinds) of the journal. Note that the accession number (A123) has been replaced by a permanent RILM number; that Harry Shlepperman's last name has been capitalized; that the translation of the title has been bracketed; and that all abbreviations and the numbers in tag *fp have been expanded to the complete words they originally represented on the abstract form. All of these changes, and punctuation, bold face, and italics, are defined for each tag by the editor and may be altered at will. Tags may be keyboarded in any sequence (or even added at a later date) since they can be arranged by computer in any specified output format. We shall also see that the abstracts as a whole may be keyboarded in random order, leaving the sorting into classes, the alphabetizing and the numbering to the computer.

In addition to the pre-printed tags, the keyboarder will also add "codes" of 2 or 3 characters to designate fonts, accents, and non-roman alphabets not available on the input keyboard. Most input devices have only 64 to 96 characters (letters, numbers, a few accents, etc.) The humanist often needs many hundreds more. By proper coding at input, the RILM system makes it possible to call forth these hundreds of characters at output. The number and variety of characters that can be stored within the "memory" of the latest photocomposition devices is, theoretically at least, unlimited. RILM editors may for example, encode and thus obtain at output:

(a) a variety of type faces and fonts (roman, italics, bold face, italic bold, small caps) in various type sizes;

(b) 18 "floating" diacriticals for use on all fonts and type sizes, and on capitals as well as lower-case letters;

(c) superscript and subscript letters and numbers;

(d) non-roman alphabets (Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, etc.) which are treated in the same way as font changes and called forth by their corresponding roman transliterations;

(e) any desired special symbols which have been prestored in the output device.

To give a few specific illustrations:

The font code $i calls for italics, until cancelled by, say, $r (roman) or $b (bold face).

Using the accent code @14, the keyboarder types K@o14benhavn to call for the Danish slashed o in København.

The non-Latin alphabet code, ¢R, in front of the word ostakovič, causes it to be printed out in Cyrillic.

Phase IV: Computer Operations

We have now arrived at the equivalent of what is referred to in the human body as the autonomic nervous system. The human brain has done its job in gathering, editing, and keyboarding the data and has also prepared detailed instructions (programs) for machine manipulation of the data. Specifically, the computer is now ready to retrieve any and all of the carefully identified (tagged) data elements, and to rearrange them in any desired combination.5 Until this point in the process, the computer has not been used. From this moment on, however, if the editor and keyboarder have done their jobs accurately, the machine can take over completely, to produce formatted, camera-ready, photocomposed pages (see Phase V), or conventional computer-driven line-printed paper. For complicated data, as will be seen below, a master proof on computer paper is desirable prior to photocomposition.

First, of course, the keyboarded data, all tagged and coded, is transferred to a nine-track machine-readable magnetic tape and "read" into the computer. A complex series of programs operates upon the data and with the speed for which computers are perhaps overly acclaimed, the following processes occur:

(a) the randomly keyboarded, individual abstracts are sorted by classification number and alphabetized by author within each class. For example, all items classified by the editor under the tag *id 26 (Classic) are put in proper alphabetical order following the items in classification 25 (Baroque), etc.;

(b) a consecutive, permanent RILM number is assigned by the machine to each item, replacing the accession number. For example, the "Mozart and the flute" entry; cited above, accessioned as number A123, is given a new permanent number of say, 369; henceforth, it will be referred to as RILM69369 ap26. This information-packed number indicates that the abstract appeared in RILM abstracts for 1969 as the 369th item for that year; it is an article in a periodical (ap) dealing with the classic or pre-classic period (26);

(c) similarly, the permanent RILM number is added to all cross-references. For example, the tag *45, originally keyboarded as part of the Mozart entry, will automatically produce a brief, author-title citation appearing in alphabetical order in the section devoted to woodwind instruments, and will direct the reader to "see 369 ap26";

(d) the author index is prepared by automatic retrieval and alphabetization of all author, editor, compiler, and translator names found in the bibliographic citation. Similarly, the subject index is created by permuting the subject names, places, and terms on the list prepared in Phase II by the editor. If desired, author and subject indices may be merged into a single alphabet;

At this point, the computer's line-printer will produce a master proof of the entire journal and index. (If a simple text is involved, one could print directly by photocomposition). The line-printer can indicate bold face by triple-striking of the characters, italics by underlining, and bold-face italics by both triple-striking and underlining. Other fonts would retain their special codes. Using a 120- or 240-character-print chain, many characters, superscripts and accents that had to be encoded on the more limited keyboarding device can be printed out. However, the original codes for characters not available on the print chain will be retained in the proof. Corrections on this master proof are made by a sophisticated though simple-to-use editing process which involves specifying exactly where the errors occur in the printout and typing in only the letters, words, or sentences that need to be added or corrected. This avoids the creation of new errors. If desired, results can be verified immediately on a cathode ray display tube or on an online typewriter keyboard.

Phase V: Photocomposition

The rearranged, corrected, and formatted magnetic tape produced in Phase IV is now ready for final outputting by photocomposition. The devices for this purpose are numerous and although they have not as yet met all of the special needs of the humanists, they are expected to do so very soon, especially as demand increases and requirements are more clearly defined. These devices can create an elegant printed page, indistinguishable from one produced by conventional "hot type", and bearing no relationship to the fuzzy, space-wasting page produced by the computer line-printer.

The process is simple: the editor defines the specific display format desired, e.g., page size, type face, sequence of data, etc.; the appropriate printing codes are applied to the magnetic tape; the machine does the rest—and at low cost.

Phase VI:

A carefully tagged machine-readable record is of enormous value to both editor and scholar; by defining his specific requirements and display formats, he is able to obtain a variety of by-products automatically—no additional programming is required. A concrete illustration of the enormous potential of such a system is to be found in RILM abstracts I/4, which contains a cumulative subject-author index for 1967 and a series of "demonstration bibliographies". These bibliographies "illustrate five possible automatic by-products of the 1967 computer-stored abstracts: (a) an individual author's output; (b) literature about a single composer; (c) a bibliography of and about thematic catalogues; (d) literature on opera from 1600-1900; and (e) dissertations reported for 1967. Each bibliography is arranged in a manner appropriate to its subject. Innumerable other by-products can be generated. For example: a) a bibliography, with or without abstracts, of all items published in a given country, arranged alphabetically by author; b) a set of library catalogue cards for any item, with full citation and abstract, and with secondary headings automatically printed at the top of each; c) a chronologically arranged bibliography of works dealing with Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts; d) a bibliography, arranged by continent and country, of articles dealing with a given topic (for instance, harmony and counterpoint, European folk music, etc.); or e) for a volume of a participating periodical, an author-subject index for the year, or a complete table of contents, arranged alphabetically by author and title and showing pagination for each article and review. These by-products can be printed in any desired format, page size, and type-font combination, with all diacritical marks in place, using non-Roman alphabets where required, and without any further typesetting or proofreading."6

The reader is invited to imagine by-products he himself might find useful. Obviously, 5- or 10-year index-cumulations will be readily obtainable. Eventually, specialized retrieval of information to answer individual research questions will be feasible, as will interdisciplinary search of several large bodies of data. The entire system could be combined with a document retrieval program employing, say, the ultra-microfiche process that compresses 3600 pages of text onto a single fiche and automatically locates and displays any page in seconds.

Other valuable aspects of the system may be mentioned. Since it is possible to keyboard different portions of a journal or book in random order, any portion can be made letter perfect, ready-to-print, while waiting for other portions to arrive. (They could be abstracts, bibliographical entries or tardy articles, depending on the publication). As soon as the final portion arrives and is properly keyboarded, the entire book or periodical can be made ready to print in a matter of hours. As indicated above, phases IV and V can both be accomplished in the wink of the computer's eye. Furthermore, for catalogues, bibliographies, inventories and the like, continuous updating is wonderfully simple.

Most of the revolutionary potentials described in this article are now being developed for use in business, government and the sciences. The ACLS/CUNY project hopes to make it possible for the humanist to profit from the miracles of modern communication, and, by concerted planning and action, to make those miracles available to him in a form tailored to his needs. The opportunity for musicology to lead the way is fortuitous; for the very reason that it is one of the youngest and smallest of the humanistic disciplines, it is perhaps best suited to the task.

1See Scientific and Technical Information; a pressing national problem and recommendations for its solution. Washington, D.C. National Academy of Sciences, 1969.

2See Thomas J. Condon, "Abstracting scholarly literature: a view from the sixties" in ACLS Newsletter XVIII/8 (Dec. 1967) 1-14.

3These are described in detail in "RILM report no. 2", published in Notes XXIX/3 (March 1968) 457-66, and in Fontes Artis Musicae XIV/1 (Jan-Apr 1968) 2-9.

4See Richard Golden, "The economies of proper data tagging," ICRH Newsletter IV/3 (Nov. 1968) p. 1 ff.

5RILM programs thus far developed are described in a series of technical reports available from the International RILM Center.

6"Editorial," RILM abstracts I/4 (1967) ii.