Abstract

With all forms of media in the world seemingly destined to become digital, a growing segment of the music industry is pushing to ensure analog is not forgotten through a recent revival of vinyl records. As compact disc sales continue to decline and digital downloads and on-demand streaming services struggle to compensate for former profits, vinyl is experiencing a surprising revival. While vinyl has long been a mature medium, technical knowledge related to vinyl production has become more and more obsolete. Though recording engineers have largely been freed from format-specific restrictions, preparing a recording for vinyl requires an intimate knowledge of the format, its capabilities, and its limitations. The sound quality of a vinyl record relies simultaneously upon a recording’s quality and the manufacturing process, and special efforts must be made in order to deliver music that will transfer successfully to vinyl. Through images, videos, and recorded examples, I will discuss the innate qualities of the vinyl format and its corresponding manufacturing process.

Introduction

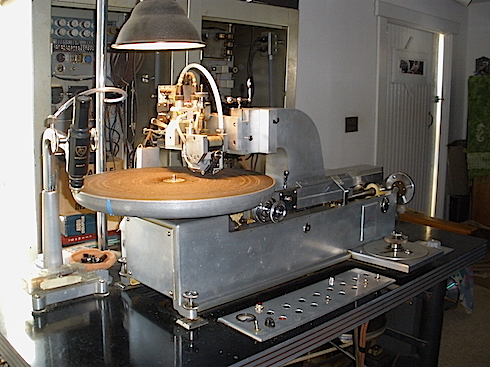

With all forms of media in the world seemingly destined to become digital, a growing segment of the music industry is pushing to ensure analog is not forgotten through a recent revival of vinyl records. As compact disc sales continue to decline and digital downloads and on-demand streaming services struggle to compensate for former profits, vinyl is experiencing a surprising revival. The resurgence of vinyl has been well documented, and sales have increased annually by at least 20 percent since 2006.1Katz, "The Persistence of Analog," in Musical Listening in the Age of Technological Reproduction, 278. See example #1.

Example #1: Global Vinyl Record Sales since 2006

While vinyl has long been a mature medium, technical knowledge related to vinyl production has become more and more obsolete. Vinyl records are comparatively expensive and time-consuming to produce, and a number of factors must be considered before pursuing a vinyl project. Though recording engineers have largely been freed from format-specific restrictions, preparing a recording for vinyl requires an intimate knowledge of the format, its capabilities, and its limitations.2Spencer-Allen, “Vinyl: Still at the Cutting Edge,” in Resolution Magazine, 48. The sound quality of a vinyl record relies simultaneously upon a recording’s quality and the manufacturing process, and special efforts must be made in order to deliver music that will transfer successfully to vinyl. Through images, videos, and recorded examples, I will discuss the innate qualities of the vinyl format and its corresponding manufacturing process. Finally, I will offer recommendations for persons who are considering vinyl as a potential release format.

Background

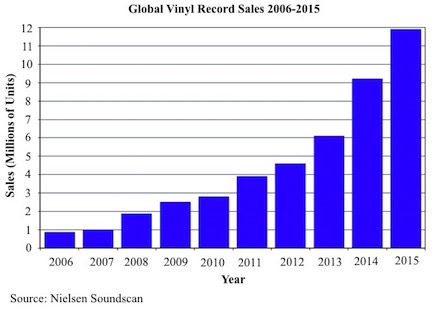

Vinyl records are an analog technology that store and reproduce a sound mechanically through grooves that represent the shape of recorded sound waves. See example #2.

Example #2: Vinyl Record Grooves under Magnification

A record groove is a single, continuous spiral that begins at the edge and progresses gradually towards the center of a disc. The groove mirrors the original sound’s waveform— a physical manifestation of acoustical energy. Sound is reproduced when a sapphire or diamond needle, known as a playback stylus, traces the grooves of a spinning record, producing mechanical vibrations that resemble the frequency and amplitude of the original sound waves. As the playback stylus traverses the groove, the minute vibrations induce an electrical current. The resulting current is then amplified and sent to loudspeakers where it is reproduced as sound.

History

Vinyl records, as a format, have a long history. Emile Berliner developed the first record turntable, known as the gramophone, in 1887. After an initial rivalry with Thomas Edison’s phonograph cylinder, records became the predominant format.3Longer possible playing times and a streamlined manufacturing process ultimately allowed disc records to supplant cylinders as the dominant record format. See Mark Coleman, Playback: From the Victrola to Mp3, 100 Years of Music, Machines, and Money, 4. Early turntables were powered by clockwork mechanisms, and records were created for playback at many different speeds. With the introduction of electrical recording technology in the early 1920s, record speeds were standardized to 78-RPM (revolutions per minute). In 1948, Columbia introduced the 33 1/3-RPM long-playing record (LP), which achieved a practical running time of around 21 minutes. As a response to the LP, RCA introduced its own record format in 1949—the 45-RPM record. Marketplace competition between the LP, 45, and 78 ignited a “battle of the speeds”, but the industry would ultimately settle upon the LP for full-length programs and 45-RPM discs for singles. The LP and 45 brought the recording industry to new heights and remained the dominant recording formats until the late 1980s.

Many believed that vinyl was destined for extinction as listeners switched to cassettes, then compact discs, and eventually digital downloads. As a result, the production methodology that was customized for the vinyl medium dwindled in the 1980s. Knowledge and equipment used for record manufacturing went into disuse, since it was no longer needed. Likewise, the vinyl-manufacturing infrastructure crumbled. Record labels, retailers, and consumer electronics companies further accelerated vinyl’s decline.4Davis, “Going Analog: Vinylphiles and the Consumption of the 'Obsolete' Vinyl Record,” in Residual Media, 225. As with each major technological change in the recording industry, certain requisite knowledge and practices were lost in the transition.

Though the number of vinyl releases declined dramatically in the 1990s, independent record labels and many devotees refused to abandon the format.5Ibid., 223. The noticeable increase in record sales that began in 2006 widened the view that there was still latent value in what many had viewed as a dead technology. Likewise, the consumer electronics industry has reported increased sales of turntables and stereo equipment, and the annual conventions of the Audio Engineering Society have included technical panels on vinyl records since 2009.6Rothenbuhler, “The Compact Disc and Its Culture: Notes on Melancholia,” in Cultural Technologies: The Shaping of Culture in Media and Society, 38. Vinyl has now gained enough of a following that artists have begun releasing their recordings on that format once again, and many retailers are stocking vinyl versions of new releases—spinning records into an unforeseen Renaissance.

Vinyl Formats

An appropriate vinyl format should be chosen based upon the type and amount of music being released. Vinyl records are manufactured in 7-inch, 10-inch, and 12-inch diameters at 33 1/3-RPM and 45-RPM playback speeds, with each format tailored for a specific use. Because of their small size, 7-inch records have a limited capacity, and are convenient for single tracks. Traditionally, the 7-inch, 45-RPM single was used for pop music singles, and the 7-inch, 33 1/3-RPM single is a low-fi format used for punk rock records. 10-inch records are less common but are typically reserved for longer singles or extended-play (EP) releases. 12-inch, 45-RPM singles are conventionally reserved for disco, dance, and hip-hop music.7Weber. “Direct-to-Disc Recording,” in Modern Recording and Music: 47. The extended run time of the 12-inch 33 1/3-RPM long-playing record (LP) makes the format suitable for classical music and album collections of commercial music.

Limitations: Duration

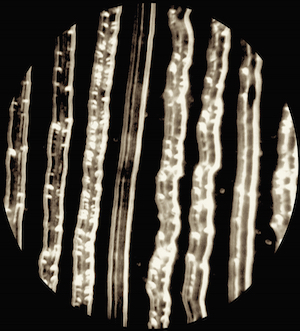

There is a finite amount of surface space on a vinyl record, and longer durations require more revolutions and a longer groove. Record duration is a battle between space and time with respect to the program content and is completely dependent upon the volume and amount of low frequency information present in the program material. The challenge is to pack the grooves as tight as possible without physically touching in order to obtain the maximum possible volume and dynamic range.8Brekus, “Aardvark Record Mastering: Mastering of Vinyl Records,” Aardvark Mastering, http://www.aardvarkmastering.com/. To prevent the grooves from colliding, an internal computer adjusts the spacing between grooves during the lacquer preparation stage. During quiet or high frequency passages, the grooves are thin and tightly spaced, but loud material and low frequency content are represented by deep and wide grooves that use more physical space on the disc. As demonstrated by example #3, longer side durations require narrower grooves, and can only accommodate program material with quieter overall volumes.

Example #3: Average VU Peak Volume for Standard 33 1/3-RPM Long-Playing Records9Henry, “The Vinyl Frontier.” >

Each record pressing facility has recommended maximum side durations dependent upon record size and speed. If the suggested time limits for a side are exceeded, there will be consequences in the forms of increased noise and distortion. Furthermore, excessive side durations may cause the stylus to deflect sideways across adjacent grooves and cause a skip—a condition known as an overcut. See example #4.

Example #4: Grooves with an Overcut

Limitation: Track Sequence

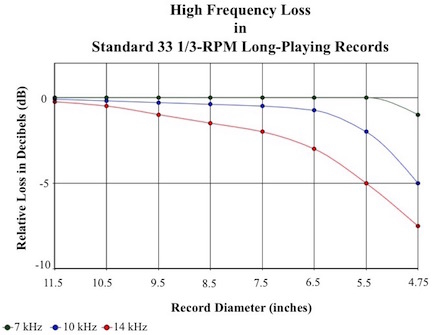

A vinyl record gradually loses resolution during playback, progressively losing high frequency information and increasing distortion as the stylus advances towards the center of a record. See example #5.10Eargle, Handbook of Recording Engineering, 389.

Example #5: High Frequency Loss in Standard 33 1/3-RPM Long-Playing Records

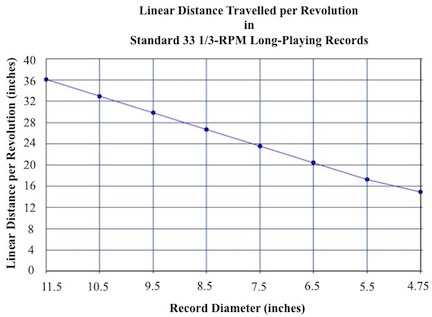

Though a record spins at a constant rotational velocity, the distance travelled in each rotation gradually diminishes. Since the circumference of the inner grooves is much less than the outer grooves, the speed of a record passing under the playback stylus is much slower in the inner grooves than the outer grooves.11This is known as diameter loss and results in a noticeable drop in treble. See Moysiaddis, “From Tape to Disc: Disc Mastering Part II,” in Modern Recording and Music, 45. See example #6.

Example #6: Declining Linear Distance per Revolution in Standard 33 1/3-RPM Long-Playing Records

As a result, information in the outer grooves of a record is traced more accurately and is better reproduced during playback.12This distortion is more properly known as tracing distortion—the inability of the playback stylus to fit into the groove in the same manner as the record stylus. See Moyssiadis, “From Tape to Disc,” 44. For maximum clarity, the more dynamic tracks should be placed in the outer grooves, and the inner grooves should be reserved for quieter tracks with less high frequency content.

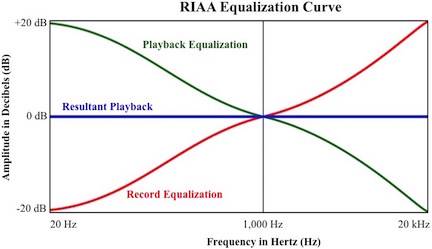

Limitation: RIAA Equalization

Vinyl records and their associated playback equipment are subject to an industry-standard equalization specification established by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in 1953. The RIAA curve attenuates bass frequencies and boosts high frequencies during manufacturing; furthermore, the inverse of the RIAA curve is applied during playback by boosting the low frequencies and attenuating high frequencies. See example #7.

Example #7: RIAA Equalization Curve

RIAA equalization permits increased record durations, reduces surface noise, and reduces the risk of damage to equipment. Without RIAA equalization, bass frequencies would cause record grooves to be so deep and wide that playback would be difficult, and record durations would be dramatically reduced. Moreover, high frequency noise would also be much more audible without the RIAA curve.

Limitation: High Frequency Content

It is possible for a vinyl record to store information that a playback system cannot reproduce; therefore, extremes in high frequency content must be controlled. High frequency information cannot be accurately traced by a playback stylus and will be reproduced as distortion. As a result, high frequency content above 8 kHz should be approached with caution, and high frequency sounds with sudden transients will have to be heavily equalized.

Limitation: Stereo Information

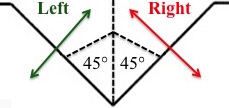

There are limitations in the amount and type of stereo information that can be stored by a vinyl record. Stereo refers to the human ability to discern the location of a sound source in the left-to-right panorama that exists between a spaced pair of loudspeakers. Vinyl records store the left and right channels on opposite sides of a V-shaped groove using a method called the 45/45 system, and a record’s groove is cut at a 45-degree angle with respect to the disc surface. One groove wall carries the left channel, and the other carries the right channel information. During playback, the stylus moves up and down as well as side to side. See example #8.

Example #8: 45/45 System

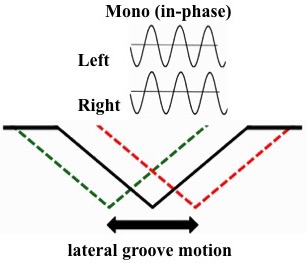

The walls of the groove represent the left and right channels through the acoustic phenomenon of phase. Phase refers to the lead or lag time present between the arrivals of two sounds. A mono signal centered between the two channels is in-phase and will generate lateral (side-to-side) groove motion. See example #9.

Example #9: Mono Groove Motion

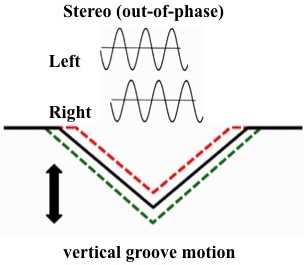

Differences in information between the left and right channels are out-of-phase and will produce vertical (up-and-down) groove motion, changing the groove depth. See example #10.

Example #10: Stereo Groove Motion

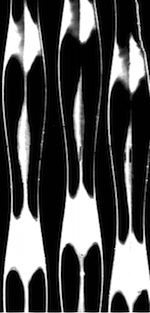

Low frequency stereo content will cause a stylus to make large vertical movements and to temporarily leave the surface of a record—a condition known as a lift-out. See example #11.

Example #11: Low Frequency Stereo Content Creates Grooves with Large Vertical Excursions

A lift-out will produce a jump or skip in a record; therefore, frequencies below 300 Hz must remain in the center of the stereo image.

Recording and Mixing

The art of recording and mixing for vinyl is in understanding and embracing the format’s limitations, and there are a number of items to consider if vinyl is a potential release format. In the digital age, it is customary for mixes to represent the entire audible frequency spectrum; however, mixing for vinyl requires a cautious treatment of the frequency spectrum.13Gibson, Mixing and Mastering, 190. Since vinyl cannot handle excessive high-frequency information, a mix shouldn’t be excessively bright. Overly brilliant cymbals, tambourines, shakers, and brass instruments should be equalized as necessary, and vocal tracks should be processed with a de-esser to control high-frequency sibilance.

The acoustic phenomenon of phase must also be considered when mixing a project for vinyl. Phase discrepancies can cause certain frequencies within a sound source to be reinforced, reduced, or cancelled completely depending upon the lag time between the arrivals of two sounds. Since out-of-phase low frequency information can cause a stylus to jump from the surface of a record, hard panning low-frequency elements, such as bass guitar and kick drums should be avoided. Effects that create out-of-phase conditions (such as flangers, phasers, and chorus effects) and improper microphone technique can also lead to tracking problems in records. Therefore, it is recommended to check all mixes by monitoring in mono. A mix should be mono-compatible without any audible problems, and a great mono-compatible mix should also sound great in stereo.14Recording engineers should listen for sounds that seem to disappear or sounds that lose a lot of treble. Though many of the above issues can be treated in later stages, they are best addressed during the mixing stage when individual instruments can be processed.

Vinyl Pre-Mastering

Since the majority of modern vinyl projects begin as digital files, it is important to have a mastering engineer familiar with vinyl’s limitations prepare a quality master recording, known as a pre-master, to serve as the audio source during the manufacturing process. Analog formats are not as forgiving as their digital counterparts, and recordings prepared for modern digital formats will not translate properly to vinyl. The aggressive use of compression and limiting that is common in digital masters should be avoided, since it can lead to distortion in a record. Vinyl manufacturing can utilize audio files that are higher resolution than the traditional 44.1kHz/16-bit sample rate files for compact disc, so files prepared for a vinyl pre-master may remain at the same resolution as the original mixes. Audio examples #12 through #16 are digital masters that were used during vinyl manufacturing. Examples #17 through #21 demonstrate the same tracks reproduced from a finished vinyl record.15These examples represent the A-side of a vinyl record. The examples of vinyl playback have been digitized for the demonstration purposes of this article.

Example #12: The Westbrook Trio, “Online Dating”, digital master

Example #13: The Westbrook Trio, “Online Dating”, digitized vinyl playback

Example #14: The Westbrook Trio, “I Like Your Status”, digital master

Example #15: The Westbrook Trio, “I Like Your Status”, digitized vinyl playback

Example #16: The Westbrook Trio, “Bad News Network”, digital master

Example #17: The Westbrook Trio, “Bad News Network”, digitized vinyl playback

Example #18: The Westbrook Trio, “Conspiracy Theorist”, digital master

Example #19: The Westbrook Trio, “Conspiracy Theorist”, digitized vinyl playback

Example #20: The Westbrook Trio, “Additional Channels”, digital master

Example #21: The Westbrook Trio, “Additional Channels”, digitized vinyl playback

As demonstrated by these examples, there are clearly audible differences in the overall sound of the digital file and its eventual transfer to vinyl. Therefore, it is important to remember that vinyl records are an analog format that will always sound inherently different than their digital counterparts due to their physical limitations.

Master Lacquer Preparation

Master lacquer preparation (also known as vinyl mastering) is the first step in vinyl manufacturing; it is a conversion process that mechanically transfers a recording onto a lacquer disc so that metal parts can be created for mass production. The master lacquer is prepared on an aluminum disc coated with a thin veneer of nitrocellulose lacquer, and a separate disc is required for each side of the record. Once master lacquer preparation begins, it is impossible to make edits or changes, so perfection must be sought throughout this process.

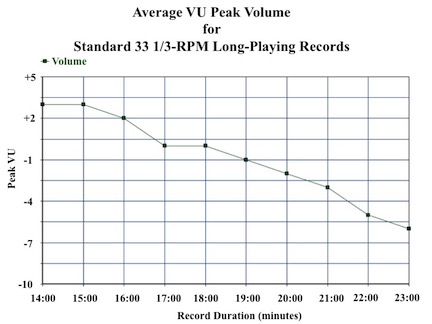

During the lacquer preparation process, audio signals played from digital files or analog tapes are sent to a machine called a disc-cutting lathe. See example #22.

Example #22: Scully Disc-Cutting Lathe

The disc-cutting lathe includes a precision turntable and a cutter head containing magnetic coils and a chisel-shaped cutting stylus made from diamond, sapphire, or ruby. The lacquer rotates on the turntable, and the cutting stylus is carefully lowered to the record surface. As the cutter head is fed an audio signal, the cutting stylus is heated, and the magnetic coils induce motion in the stylus. The cutting stylus vibrates in sympathy with the incoming audio signal and etches grooves into the lacquer that are analogous to the original recorded sound. An internal computer examines the incoming audio signal and moves the cutter head across the surface of the lacquer, adjusting the width and spacing of the grooves as necessary. Example #23 demonstrates the lacquer preparation process on a Neumann VMS-70 Disc-Cutting Lathe. See example #23.

Example #23: Lacquer Preparation with a Neumann VMS-70 Disc-Cutting Lathe

The signal levels and quality of cut are carefully monitored during the lacquer preparation process. Depending upon the suitability of an audio source for vinyl, master lacquer preparation may require additional signal processing, and engineers will apply equalization, compression, or limiting as necessary in order to obtain the optimum result. At the conclusion of a side, the grooves are examined closely under a microscope to ensure that there are no anomalies or imperfections. See example #24.

Example #24: An Engineer Checks a Master Lacquer for Errors

Once master lacquers have been prepared for both sides of a record, the lacquers are inscribed with a unique serial number (called a matrix) for identification purposes and promptly sent to a record-pressing plant where they are used for product manufacture. The finished master lacquers serve as the template from which all copies of a record are made.

Reference Lacquers

A completed master lacquer can never be played because it could be damaged by playback. Since a finished master lacquer must remain flawless as the parent source of the metal stampers, it is common to prepare one or more reference lacquers (also known as acetates) beforehand. References lacquers can be played on a turntable, and their playback closely approximates that of a vinyl pressing. Reference lacquers degrade rapidly but can be played back 20 to 25 times without serious quality deterioration.16Eargle, Sound and Recording, 300. The instantaneous playback capability of reference lacquers provides the best opportunity to preview and evaluate a record’s quality before a project reaches advanced stages of production. See example #25.

Example #25: Reference Lacquer

Electroplating

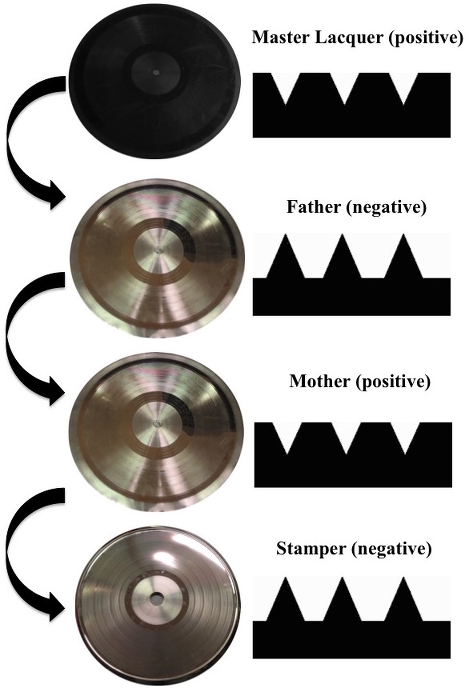

Electroplating is an intricate metal-to-metal transfer process that yields the metal parts used for record pressing.17Eargle, Handbook of Recording Engineering, 390. When the master lacquer reaches the pressing plant, it is rinsed with soap and water and given a coating of silver nitrate to make it electrically conductive. The lacquer is then submerged into a nickel sulfamate solution that has an electrical current passing through it, and nickel bonds to the disc through a chemical reaction. When plating is complete the master lacquer is removed from the solution, peeled away, and discarded. The resulting metal part, known as the father, is a negative of the master lacquer and has ridges instead of grooves. The father is then dropped back in the nickel bath and electroplated again to produce another metal part called the mother—a metal replica of the original master lacquer.18For large production runs, the father can be plated several times to produce several mother plates, and the mother can be plated several times to produce many stampers. See Moyssiadis. “A Record Producer’s and Consumer’s Guide to Better Record Pressings,” in Modern Recording and Music, 57. The mother is immersed in the nickel bath and plated a final time to produce another part known as a stamper—a negative copy with ridges that serves as the mold for pressing the records.19A stamper is only good for so many pressings before it wears out, so metal mothers may be used to produce many stampers. See Moyssiadis, “A Record Producer’s and Consumer’s Guide to Better Record Pressings,” 57. See examples #26 and #27.

Example #26: Steps of the Electroplating Process

Example #27: The Electroplating Process

Lastly, the stampers are formed to fit the record presses and sent to the chosen pressing plant.

Record Pressing

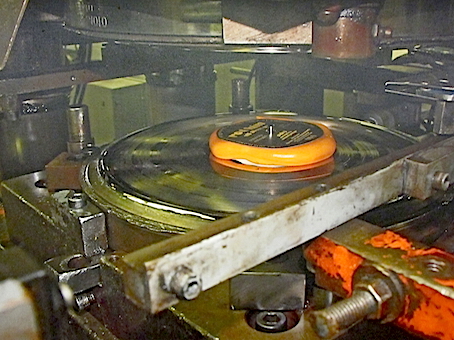

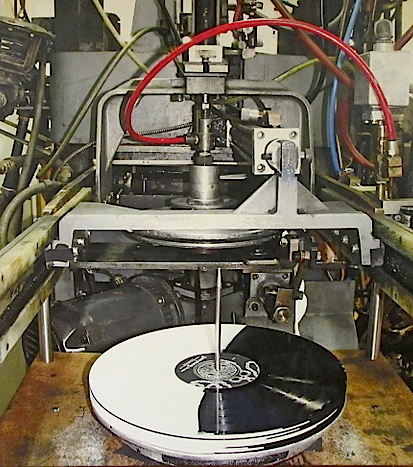

During the pressing process, stampers are fitted to the record press—one for each side of the record (A and B sides). Vinyl granules are heated and melted into a wedge called a biscuit, and record labels are affixed to the press. The biscuit is fed into the press, rapidly heated, and stampers are sandwiched together so that the vinyl casts to the shape of the stampers. During this process, the grooves representing the original sound waves are formed into the vinyl, and the record label is also pressed into the vinyl. Excess vinyl is then trimmed away from the outer edges of the record. The center hole is drilled, and records are then put on a rack to cool. The finished records are then examined, inserted into a dust sleeve, placed into a record jacket, and shrink-wrapped with plastic. See examples #28, #29, and #30.

Example #28: Plates, Biscuit, and Labels in Press

Example #29: A Record is Trimmed

Example #30: Finished Records Cooling

Test Pressings

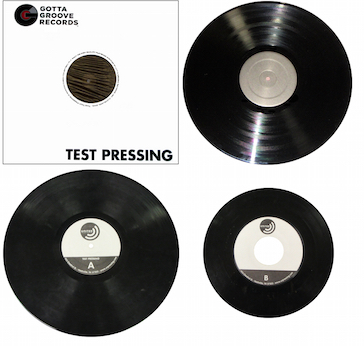

Before mass production of a record begins, a set of test pressings is made. Test pressings are identical to the finished product and represent the final opportunity to evaluate a record’s sound quality before mass production begins. The appropriate parties will listen to the test pressings, evaluate the sound quality, and carefully document any playback problems or physical anomalies. Consistent problems with test pressings necessitate additional stages of manufacturing, such as producing new master lacquers or re-plating.20Carefully document any consistent clicks and pops among a set of test pressings with approximate timings; these anomalies indicate physical damage to the record stampers. See Moyssiadis, “A Record Producer’s and Consumer’s Guide to Better Record Pressings,” 60. Once test pressings are approved, the full pressing run may commence. See example #31.

Example #31: Test Pressings from Different Pressing Plants

General Recommendations for Vinyl Projects

Despite vinyl’s renewed popularity, the vinyl manufacturing process is often an intimidating one for uninitiated artists. There are definite limits present in vinyl’s current manufacturing infrastructure, and pressing plants have been overwhelmed by demand from the vinyl revival. Vinyl manufacturing is a lengthy, complicated process that requires manual labor throughout many stages of production. Current demand exceeds production capacity, and expensive components and antiquated equipment have resulted in prolonged turnaround times and quality issues. The possibility always exists that something could go wrong during the manufacturing process, and problems can occur anywhere in the production chain. Therefore, it is recommended to contact a pressing plant for guidelines and to plan the details of a project’s release in advance to avoid production delays.

There are 27 vinyl-pressing plants currently operating in the United States and 43 more abroad.21“Vinyl Record Pressing Plants: An Ultimate List of Companies That Do Vinyl Record Pressing,” https://vinyl-pressing-plants.com/manufacturing/vinyl-pressing-plant/ In addition, there are currently many specialized mastering facilities that can produce master lacquers. Although many of the large pressing plants handle their own electroplating, dedicated electroplating facilities also exist. Most modern record pressing facilities offer their services as part of a package including vinyl mastering, electroplating, and pressing. However, hiring specialists for the different portions of the production process can improve the quality in some cases and expedite a project’s completion date. Regardless, it is imperative to establish and maintain communication with those handling the manufacturing process.

Recommendations: Master Lacquers

Transferring a recording to a master lacquer is a decisive process that exerts a major influence on how a record will sound. Artists may have the chosen pressing plant prepare the master lacquer or utilize an independent lacquer preparation engineer. Though using a record pressing plant is the most convenient option, pressing plants prepare a large number of lacquers and do not always provide the same attention to detail as an independent specialist. Hiring an independent lacquer preparation engineer provides an open line of communication with the person handling this crucial process, but it also takes extra time to schedule.

There are items that are necessary, regardless of who is preparing the master lacquers. Supply the highest resolution audio files possible for lacquer preparation. A track-list with approximate running times should also be provided for lacquer preparation with the approximate durations and sequence of all tracks, organized as the A and B-sides of the record.22If master lacquers are to be prepared from analog tape, tracks should be organized onto separate tape reels for the A and B-sides on ¼” or ½”, two-track tape with 1 kHz, 10 kHz, 100 Hz alignment tones printed at the beginning of each reel. According to Gibson, the calibration tones will be used to adjust the tape machine for proper performance during the mastering process. See Gibson, 26. A matrix number should be chosen and provided for all involved in the manufacturing process—a unique alphanumeric serial number that will be used for identification and cataloging purposes during manufacturing.

Reference lacquers should always be ordered, as they provide the only means of adjudicating sound quality before a project reaches advanced stages of manufacturing. A reference lacquer should retain the character of your mixes and the general tonality of a project. Any distortion, pops, clicks, skips, or surface noise present in a reference lacquer should be carefully noted, for these problems require adjustments in the lacquer preparation process. When playback of reference lacquers is satisfactory, then the master lacquer may be prepared. Though lacquer preparation is often done without the artist or engineer in attendance, it is recommended to attend, if possible, in order to provide input and to observe the process firsthand.

Recommendations: Electroplating

Although electroplating is included in most vinyl packages, the manufacturing of metal parts represents the main production bottleneck in the vinyl industry’s current infrastructure. Utilizing a dedicated electroplating facility can sometimes expedite the production process, and artists may opt to have a master lacquer sent directly to a specialized electroplating plant. Upon receipt of master lacquers, an electroplating plant will promptly begin the plating process—manufacturing parts for specifically for the selected pressing plant.

A decision must be made to use either two-step or three-step electroplating, which can be determined by the size of a production run. The two-step electroplating process involves the father being peeled from the master lacquer and electroplated again to produce a mother plate. In this situation, the mother plates are stored for archival, and the father plates are used for stamping. In three-step electroplating, the mother plate is electroplated to make more stampers; it is used in large production runs to avoid having to cut additional lacquers.23The three-step electroplating process is outlined in detail in this article. One set of stampers can press approximately 1,000 records before wearing out. If more than 1,000 records will be pressed, artists should choose three-step electroplating.

Recommendations: Pressing Options

There are many options available in vinyl pressing, but each option comes at a cost. The actual cost of the pressing process depends upon a number of variables: quantity, color, and weight. Most record pressing plants have a minimum number of records that must be pressed in an order; however, price per copy usually declines when a greater volume of records are ordered. Many different colors are available for vinyl; however, colored options are generally more expensive than the traditional black vinyl. As a record’s weight increases, the quality of sound also increases. Standard weights of 12-inch records range from 120 to 160 grams, with 180-gram vinyl usually considered as audiophile quality. For 7-inch records, record weights are usually from 40-70 grams.24Jesse Cannon and Todd Thomas, Get More Fans: The DIY Guide to the New Music Business, 433. For 7-inch records, there is an additional choice of having a small or large hole in the center. The large hole was traditionally used; however, some have argued that the small hole provides higher fidelity.25Cannon and Thomas, 433. Finished records are assembled in packaging—inner sleeves, jackets, and shrink-wrap per client specifications. Artists may opt to include additional features with records such as digital download cards and inserts.

Recommendations: Test Pressings

The appropriate parties will receive a set of test pressings shortly after the production of stampers. Test pressings are intended to identify manufacturing issues, such as pops, skips, consistent tracking issues, and surface noise. Test pressings are not intended to review for subjective audio considerations such as levels, sibilance, and distortion as these should be identified during the lacquer preparation process. If an issue exists with a test pressing, the issue will be apparent on each copy of the pressing in the exact same spot. If there are problems with test pressings, it is important to provide specific information to the pressing plant in order to remedy the problem. Carefully document the side, track number, and time markers that are as close as possible to where the issues are present. The pressing plant should make every effort to remedy any manufacturing issues in as efficient a manner as possible. Following approval of test pressings the full pressing run will commence, and the finished records should be received soon thereafter.

Conclusion

While it was somewhat inevitable that digital distribution would become the music industry’s standard, the vinyl revival demonstrates that analog media can still be appreciated and valued in the digital age. Thus far, vinyl has outlasted every format intended to replace it. Though vinyl records remain a tiny fraction of total industry sales, the format is in no danger of dying.26Owsinski, The Mastering Engineer’s Handbook: The Audio Mastering Handbook, 79. Despite the technical limitations of the vinyl medium, there’s an indescribable magic in the production of a good record. From an artist’s standpoint, there is nothing quite like experiencing a completed project on vinyl as the needle reproduces the nuances of a production. Vinyl will likely maintain a niche position in the industry for years to come, and for these reasons, the art of vinyl production must be kept alive.

Acknowledgements

It takes a commitment to excellence to make the vinyl experience worthwhile, and this research has benefited from the contribution and support of many music industry professionals. The Westbrook Trio’s album Postmodern Man served as the case study for this project. Though the album was released digitally and as a compact disc, a limited number of copies were pressed to vinyl. The Westbrook Trio combines jazz, soul, rock, and progressive rock influences and features Randy Westbrook (keyboards), Thomas Usher (bass), and Jacob Hamrick (drums and percussion). Postmodern Man was recorded and mixed in the Eastern Kentucky University Recording Studio. Vinyl pre-masters were prepared by Daniel Porter at DP Sonics in Indianapolis, IN, and master lacquers were prepared by Cameron Henry at Welcome to 1979 Studios in Nashville, TN. Mastercraft Metal Finishing in Elizabeth, NJ produced the record plates and stampers, and the records were pressed by Gotta Groove Records in Cleveland, OH.

Notes

1 Katz, "The Persistence of Analog," in Musical Listening in the Age of Technological Reproduction, 278.

2 Spencer-Allen, “Vinyl: Still at the Cutting Edge,” in Resolution Magazine, 48.

3 Longer possible playing times and a streamlined manufacturing process ultimately allowed disc records to supplant cylinders as the dominant record format. See Mark Coleman, Playback: From the Victrola to Mp3, 100 Years of Music, Machines, and Money, 4.

4 Davis, “Going Analog: Vinylphiles and the Consumption of the 'Obsolete' Vinyl Record,” in Residual Media, 225.

5 Ibid., 223.

6 Rothenbuhler, “The Compact Disc and Its Culture: Notes on Melancholia,” in Cultural Technologies: The Shaping of Culture in Media and Society, 38.

7 Weber. “Direct-to-Disc Recording,” in Modern Recording and Music: 47.

8 Brekus, “Aardvark Record Mastering: Mastering of Vinyl Records,” Aardvark Mastering, http://www.aardvarkmastering.com/. To prevent the grooves from colliding, an internal computer adjusts the spacing between grooves during the lacquer preparation stage.

9 Henry, “The Vinyl Frontier.”

10 Eargle, Handbook of Recording Engineering, 389.

11 This is known as diameter loss and results in a noticeable drop in treble. See Moysiaddis, “From Tape to Disc: Disc Mastering Part II,” in Modern Recording and Music, 45.

12 This distortion is more properly known as tracing distortion—the inability of the playback stylus to fit into the groove in the same manner as the record stylus. See Moyssiadis, “From Tape to Disc,” 44.

13 Gibson, Mixing and Mastering, 190.

14 Recording engineers should listen for sounds that seem to disappear or sounds that lose a lot of treble.

15 These examples represent the A-side of a vinyl record. The examples of vinyl playback have been digitized for the demonstration purposes of this article.

16 Eargle, Sound and Recording, 300.

17 Eargle, Handbook of Recording Engineering, 390.

18 For large production runs, the father can be plated several times to produce several mother plates, and the mother can be plated several times to produce many stampers. See Moyssiadis. “A Record Producer’s and Consumer’s Guide to Better Record Pressings,” in Modern Recording and Music, 57.

19 A stamper is only good for so many pressings before it wears out, so metal mothers may be used to produce many stampers. See Moyssiadis, “A Record Producer’s and Consumer’s Guide to Better Record Pressings,” 57.

20 Carefully document any consistent clicks and pops among a set of test pressings with approximate timings; these anomalies indicate physical damage to the record stampers. See Moyssiadis, “A Record Producer’s and Consumer’s Guide to Better Record Pressings,” 60.

21 “Vinyl Record Pressing Plants: An Ultimate List of Companies That Do Vinyl Record Pressing,” https://vinyl-pressing-plants.com/manufacturing/vinyl-pressing-plant/

22 If master lacquers are to be prepared from analog tape, tracks should be organized onto separate tape reels for the A and B-sides on ¼” or ½”, two-track tape with 1 kHz, 10 kHz, 100 Hz alignment tones printed at the beginning of each reel. According to Gibson, the calibration tones will be used to adjust the tape machine for proper performance during the mastering process. See Gibson, 26.

23 The three-step electroplating process is outlined in detail in this article.

24 Jesse Cannon and Todd Thomas, Get More Fans: The DIY Guide to the New Music Business, 433.

25 Cannon and Thomas, 433.

26 Owsinski, The Mastering Engineer’s Handbook: The Audio Mastering Handbook, 79.

Bibliography

Bartlett, Bruce. “Recording Techniques: Part 10,” Modern Recording and Music 9, no.2 (February 1983): 24-29.

Boden, Larry. Basic Disc Mastering. Glendale, California: Larry Boden, 1980.

Brekus, Paul. “Aardvark Record Mastering: Mastering of Vinyl Records.” Aardvark Record Mastering. Accessed November 1, 2015. http://www.aardvarkmastering.com/.

Burgess, Richard J. The History of Music Production. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Byrne, David. How Music Works. San Francisco: McSweeney’s, 2012.

Calibi, Greg. “Twenty-First Century Vinyl Mastering,” In Mixing, Recording, and Producing Techniques of the Pros 2nd Edition, edited by Rick Clark, 187-189. Boston: Course Technology PTR, 2011.

Cannon, Jesse and Todd Thomas. The DIY Guide to the New Music Business. 2nd ed. Union City: Musformation, 2017.

Chitode, J.S. Consumer Electronics. Pune, India: Technical Publications, 2002.

Coleman, Mark. Playback: From the Victrola to Mp3, 100 Years of Music, Machines, and Money. New York: Da Capo Press, 2003.

Cunningham, Mark. Good Vibrations: A History of Record Production. London: Sanctuary Publishing, 1998.

Daley, Dan. “Welcome to 1979 Studios: Direct-to-Disc Recording and Vinyl Plating.” in Sound on Sound (May 2016): 186-191.

Davis, John Siebert. “Going Analog: Vinylphiles and the Consumption of the 'Obsolete' Vinyl Record.” In Residual Media, edited by Charles Acland, 222-238. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Dawson, Jim and Steve Propes. 45 RPM: The History, Heroes, and Villains of a Pop Music Revolution. San Francisco: Backbeat Books, 2003.

Eargle. Handbook of Recording Engineering. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.: 1986.

Eargle, John. Sound and Recording. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.: 1976.

Gibson, Bill. Mixing and Mastering. New York: Hal Leonard, 2007.

Gronow, Pekka and Ilpo Saunio. An International History of the Recording Industry. New York: Cassell, 1998.

Henry, Cameron, “The Vinyl Frontier.” Presentation at the 135th International Convention of the Audio Engineering Society, New York, NY, October 20, 2013.

Holmes, Thom. The Routledge Guide to Music Technology. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Izhaki, Roey. Mixing Audio: Concepts, Practices, and Tools. Burlington: Focal Press, 2007.

Jones, Steve. Rock Formation: Music, Technology, and Mass Communication. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications, 1992.

Katz, Mark. "The Persistence of Analog". In Musical Listening in the Age of Technological Reproduction, edited by Gianmario Borio, 275-290. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015.

Morris, Jeremy Wade. Selling Digital Music, Formatting Culture. Berkley: University of California Press, 2015.

Moyssiadis, David. “A Record Producer’s and Consumer’s Guide to Better Record Pressings”, Modern Recording and Music 3, no. 3 (December 1977): 56-64.

Moyssiadis, David. “From Tape to Disc: Disc Mastering Part II”, Modern Recording and Music 9, no. 2 (September 1977): 44-52.

Osborne, Richard. Vinyl: A History of the Analog Record. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

Owsinski, Bobby. The Mastering Engineer’s Handbook: The Audio Mastering Handbook. 2nd ed. Boston: Thomson Course Technology, 2008.

Rothenbuhler, Eric W. “The Compact Disc and Its Culture: Notes on Melancholia.” In Cultural Technologies: The Shaping of Culture in Media and Society, edited by Göran Bolin, 36-50. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Rumsey, Francis and Tim McCormick. Sound and Recording. 6th ed. Oxford: Focal Press, 2009.

Ryan, Kevin L. and Brian Kehew. Recording the Beatles: The Studio Equipment and Techniques Used to Create Their Classic Albums. Houston: Curvebender Publishing, 2006.

Sevcenko, Melanie. “Time for Vinyl to Get Back in its Groove after Pressing Times.” September 20, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/sep/20/music-vinyl-records-new-pressing-plant-portland-oregon.

Shuker, Roy. Wax Trash and Vinyl Treasures: Record Collecting as a Social Practice. Farnham: Ashgate, 2010.

Spencer-Allen, Keith. “Vinyl: Still at the Cutting Edge.” Resolution Magazine (November/December 2003): 44-48.

“Vinyl Record Pressing Plants: An Ultimate List of Companies That Do Vinyl Record Pressing.” Vinyl Pressing Plants. Accessed August 20, 2017. https://vinyl-pressing-plants.com/manufacturing/vinyl-pressing-plant/.

Weber, Jeff. “Direct-to-Disc Recording,” Modern Recording and Music 2, no.6 (June 1977): 44-48.