Abstract

The ability to successfully thrive in our current digitally-integrated entertainment industry can be explored through the exchange of ideas using tools that assist in human development. As predicted, the current climate of technological integration sets the stage for greater development and efficiency of interpersonal and analytical skills (Gardner, 2005). Yet, the evolution of constructivist approaches to learning suggests that efficacy has its place in various contexts and in varying depths (Vygotsky, 1978; Bandura, 1971, 1994; Deci & Ryan, 2008; Patton et al., 2017). Building upon the concept of efficacy in the entertainment industry, this paper introduces a model for contextualizing professional development for creative professionals. The article provides implications for framing creative development in the larger academic and entertainment communities that encourages discussion around creative sustainability.

Rush Hicks

In the age where information and access are digital, engagement becomes immediate, urgent and integrated (Gardner, 2005). As our work is more digitally-connected, we become more reliant on digital tools to engage ourselves, achieve tasks, or develop skills (Patton et al., 2017). The use of tools to accomplish a given goal occurs in different ways and in a number of contexts. Working in the music industry as an educator and creative for over a decade, I encounter various ways creative professionals engage tools to assist their development. From studying song lyrics on the internet, to analyzing the performance of an expert, our current access to technology provides many opportunities for creative development and engagement. Having immediate access to tools does not translate to a creative professional’s development, however.

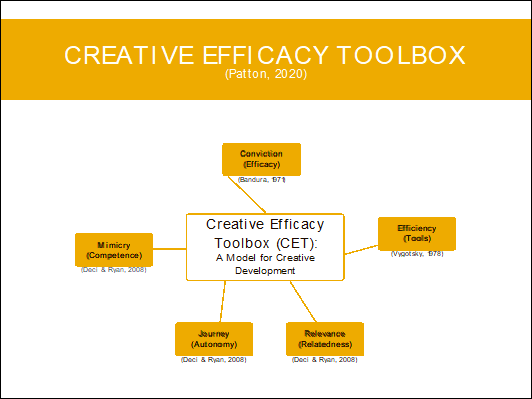

Goals attainment and skills development in the context of the entertainment industry are particularly intriguing given the industry’s volatility. There seems to be a pre-requisite to success. For instance, eager musical artists and professionals—collectively described here as creatives—pursuing creative careers must display a certain level of competency and quantifiable success before taken seriously in bigger markets (i.e. an artist looking to sign with a label may need to demonstrate success in music views/downloads, shows performed, and social media buzz, etc.) Yet the ability of the creative to thrive in their professional goals, defined here as creative efficacy, is something not well researched, no less well-examined practically. While the context of the entertainment industries makes it novel, the phenomenon of efficacy is not new; and it has been the discussion of theorists and researchers approaching a century (Vygotsky, 1978; Bandura 1971, 1997; Gardner, 2005; Tierney & Farmer, 2002; Deci & Ryan, 2008). This article introduces the Creative Efficacy Toolbox (CET), a model of professional development that can be used to guide systematic facilitation of development meant for the creative.

In order to contextualize CET, I establish the significance of creative efficacy as it differs from prior applications of creativity and self-efficacy. In the review of literature, I then provide background into the current, digitally-driven landscape of the music industry as well as examine the need for creative development. Next, I deconstruct CET and provide rationale, exploring the utility of the theoretical frameworks informing the model. Finally, I offer implications for practical application, as well as recommendations for further research of the professional development of creatives.

Significance of Creative Efficacy

Efficacy is not a new term and it is not cultivated only through an institutionalized process. Building the awareness of one’s process and developing into self-actualization, based on Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs, does not happen in a vacuum but through interaction with others. There is merit in formalized learning, yet learning is dynamic and occurs in myriad contexts and ways. While the constructivist approach of self-efficacy––one’s perceived ability to thrive––has been used in various contexts, the exploration of creativity and efficacy is widely adopted in business management. For instance, the concept of creative self-efficacy (CSE) introduced the creative approach to one’s professional development.

Creative Self-efficacy (CSE)

This is the work that Tierney and Farmer (2002) defined as a confidence, or belief, that one has the ability to produce creative outcomes. This work has large implications in the workforce in general, specific to managers and leaders tasked to lead productive teams. As such, CSE speaks to the business professional applying creativity in their role in anticipation of greater outcomes. However, it leaves no voice for the creatives’ unique experiences as a professional. Thus, examining creative efficacy relative to the entertainment industries provides insight to this constructivist approach.

Creative Efficacy

In contrast to CSE, creative efficacy is the result of work creative professionals do to thrive in their creative industries, irrespective of their level of experience. While the attitude towards creative self-efficacy and one’s ability to realistically achieve his or her creative possibilities differs, the context and type of professional matter (Beghetto et al. 2011; Haase et al. 2018). The exploration of efficacy in this context merits academic discussion due to the lack of prior research coupled with the volatile, exciting nature of the creative industries. According to the meta-analysis conducted by Haase et al. (2018), tests of performance as well as indicators of success may be key factors in how a creative professional is able to thrive in creative self-efficacy, though it warrants more investigatory data before higher-level analyses might be engaged. The exploration of creative efficacy, then, provides further context from which the creative and academic communities might use to develop and share relevant best practice.

Literature Review: Creative Development in the Music Industry

The entertainment industries have evolved tremendously, and so has public consumption. Specific to the music industry, the way consumers engage today is not what it used to be, yet our industry has always absorbed this change (Passman, 2019). From the time when radio disrupted the public performance of music, to when television came as a threat music industry, and even to the disruption of tangible music consumption due to piracy and streaming—the music industry has adapted and continues to evolve (Herstand, 2017; Passman, 2019; Baskerville & Baskerville, 2020). A consequence of a thriving and volatile industry is that people need entertainment, and thus creatives continually develop and evolve in light of this demand.

The Evolving Music Industry

The rapid changing of media and how consumers engage can be seen as a unique hallmark of the music industry, requiring creatives to develop a certain stomach for volatility and market saturation in their markets. For instance, both well-established and independent creatives work hard to find creative and sustainable ways to monetize their products and brand, given the current landscape of technology disruption. This change requires greater levels of efficacy and gall, characteristics of well-known creative vocalists coined as “kill spirit” in the American documentary, Twenty Feet From Stardom (Neville, 2013). This kill spirit with which the creative or creative industry professional must familiarize and adopt is more than just how one pursues their creative goals, but it also speaks to the development of one’s brand and how they interact with their world. In a loosely-regulated industry like the music business, not developing this efficacy may be a hindrance to any potential number of raw talent who lack tools to further their success or at least be on par with their peers in the same markets.

Irrespective of the challenges that the music industry has endured, the industry perpetuates exceptional talent who can translate their craft and their goodwill to the masses. Yet, industry leaders grapple with how the developmental process is respected or even stewarded. Years before Universal Music Group’s CEO, Lucian Grainge, came into leadership at this major label behemoth, he very clearly identified problems of industry practice and offered solutions that he believed contributed best: creative development, engaging technology companies and other businesses more efficiently, as well as strengthening how consumers engage with artists (Atkinson, 2011). A champion for creative development and sustainable global impact, Grainge enjoyed a very successful year in 2019, and attributed much of UMG’s continued success to expertise, innovation, resources, passionate people and the urgency of creativity and community (Stassen, 2019). Given the industry’s volatility, consumer engagement with technology and the ease with which hopeful creatives can engage their craft and brand, the concept of creative development seems to be more urgent now than ever.

Creative Development in the Music Industry

In the consideration of creative development, the ways in which creatives engage their goals look very different, and are not always characterized by a formalized or systematic approach. Whether in or out of the classroom, learning happens through authentic engagement. According to the New York Times, (as cited in Rensin, 2003) one has to engage the entertainment business from the bottom to be successful in identifying and cultivating talent:

The trade itself cannot be taught in a seminar, being smoke and mirrors, three-card monte and the ability to recognize talent. But in mingling with the real agents and navigating the city’s nightlife after work, the baby moguls can absorb certain lessons in the craft, including making connections, feigning importance (never place a call your secretary can place) and mastering the art of becoming someone’s best friend. (p. xvi)

The peculiar classroom of raw experiences is too familiar to the creative and those who work with them.

In the context of the music industry, there are many brilliantly gifted influencers who may not have endured formalized training yet exhibit evidence of gifts worth being critiqued at a high level. For example, in the show World of Dance, where amateur dancers perform on the spot and are critiqued by industry-leading judges, executive director Jennifer Lopez gave constructive feedback to an amazing group of young dancers who could mimic synchronized movement and incorporate popular styles at a high level, but lacked interpretation in critical parts of the song (Lopez, 2020). The feedback showed the level of critique that serious creatives must normalize when it comes to sharpening their craft, even at a young age. Whether our greatest creatives cultivated their gifts in a formal way or endured a form of training via intentional or unintentional expert facilitation, the dynamics of creative efficacy have yet to be adequately explored in the academic and public spaces.

Literature Review Summary

The review of literature shows how loose regulation and technology disruption influence the volatility of consumer behavior and creative efforts. The current access creatives and consumers have to create and share content provides opportunities for brand visibility, but it also underscores the differences in talent. Lack of development can lead to product and brand failure in the marketplace for many creatives, particularly for those without any access to tools to support their endeavors. Yet, many leaders in this current music business landscape are confident in the viability of the industry and in the creatives and consumers that sustain it. In response, various experts and organizations take part in finding and developing talent via regional, national or international talent searches, competition shows, social media, and other methods of discovery often providing vital feedback as critique. Prior literature acknowledges the need for creative development in the music business, but offers little in terms of how creatives might systemize their development. The following section examines the Creative Efficacy Toolbox (CET) model and the theoretical frameworks that inform it.

Decomposing the Creative Efficacy Toolbox: Theoretical Frameworks and Rationale

This section considers a theoretical basis for how creatives arrive at satisfactory levels of success and self-defined efficacy, furthering well-established and critiqued models that intersect creatives’ developmental processes. With the advent of technology, the creative professional can have immediate access to tools of development, and in their toolbox are aspects that strengthen the creative’s desired goals. For instance, the ability to mimic experts, confront one’s relevance, define one’s journey, and use tools––at times with expert facilitation––to further assist their goals all are key indicators of a creative’s conviction in their craft. These indicators are all rooted in educational psychology through the lenses of Vygotsky (1930/1978), Bandura (1971), and Deci and Ryan (2008).

Figure 1: Creative Efficacy Toolbox Model

Facilitated Tools that Enhance Efficiency

According to early 20th century educational theorist, Vygotsky (1978), the learner is assisted through a socio-constructivist approach that consults the experiences of the learner, or the creative for the purposes of this context. This process of development was underscored through the assertion that culture tends to dictate behavior. And to this extent, development provides tools that assist its members in their thriving, as experienced through authentic socio-cultural engagement (ibid). These cultural tools, as Vygotsky introduced, are essential to understanding the intricacies of culture—what makes it work, what does not work, what is acceptable, etc.

We see the need for cultural tools in the music context even to this day. For example, consider a popular way musicians communicate through a more simplified musical notation, called Nashville Numbers. As such, musicians codify and communicate chordal direction in music using a number system. These tools absolutely assist in communicating at a satisfactory level within our environment(s), depending on one’s engagement. For the purpose of this context, one’s ability to successfully use tools to enhance their experiences and/or goals is a mark of their efficiency—or one’s experience with producing better outcomes. These tools take many forms, from researching current news and acquisitions in our industry, to using digital service providers (DSPs) to exploit master recordings and provide analytics for further exploitation of an artist or group’s brand. Tools, especially when accessed quickly through digital means, represent a huge advantage to the modern-day creative as a continual learner.

In addition to the concept of cultural tools is the application of expert facilitation, which provides the opportunity for greater efficiency. Vygotsky (1978) introduced facilitation through the concept of zone of proximal development (ZPD), where learners engage with an expert of a task at a level slightly above their comfort, or just above where the learner can achieve a desired goal confidently. ZPD, then, was suggested as a tool accessed by psychologists and educators through which one’s internal developmental processes could be understood (pp. 87-89).

The implication of this tool, as it relates to facilitation, is knowing that the learners’ observed abilities reflect that which is both imitated and independently expressed. In context, this requires the facilitator to have a deeper understanding of maturation in the developmental process as they engage the creative beyond his or her prior level of competence and comfort. As a creative builds, it is also important to develop maturity in one’s growth so that independent efficacy and identity can be founded. Finally, it is key to note that in a digitally-integrated society where there is a saturation of information, the creative may not engage directly with expert facilitation. Creatives, however, still engage with experts through attending performances, analyzing masterclasses and recorded performances, engaging in inquiry, or through other methods of indirect engagement, while still consulting their own comfort levels and goal attainment. I consider this an authentic engagement of ZPD. Though it does not conform to a traditional method of transferring knowledge, exposure to expert modeling has the potential to confront the creative with what is possible beyond their current level of maturity and development.

Competence, Autonomy and Relatedness: Drivers of Creative Identity

In further establishing creative identity, creatives must also engage their development throughout an authentic process that contextualizes the creative constructivism, socio-culturally. In other words, the creative must engage their world with their unique contributions. In building capacity for awareness and efficacy, researchers Deci and Ryan (2008) provided a theoretical framework that has implications in the creative space as well. According to Ackerman and Tran (2020), the self-determination theory (SDT) model highlighted three key components of how learners engage perceived efficacy with their world—competence, autonomy and relatedness. These constructs fit well within the context of creative development, as creatives endure to insert their point of view and find their place in such a huge and volatile creative industry. Creatives must engage the following: how they measure up in terms of the competence of their skills and gifts; how they control their own development in the socio-cultural context in which they learn through autonomy; and their continued development in light of how they relate to others.

Competence. As discussed, motivated creatives grow from opportunities to receive quality feedback or critique. While it is extremely valuable to grow from explicit feedback from experts, this feedback process is not just relegated to authentic and direct exchange, however. For this reason, the concept of competence can also interpreted by the process of mimicry, the concept of replicating identified and desirable patterns of expression. In the absence of direct engagement, creatives maximize exposure to examples of excellence, commonalities or failures simply by accessing tools that allow for playback and study of any expressed creative phenomenon. Mimicry is a tool for learning, as well as one learning through failures of pertinent influencers.

Engaging mimicry is akin to exercising the muscle of competence. It is through the process of encountering and confronting repeated examples that encourages confidence in one’s growth. At surface, mimicry can be described as remembering and understanding, the lowest levels of learning according to Bloom’s Taxonomy (McDaniel, 2010). Yet creatives take their journey past mimicry and push through high-level thought processes to create new expressions of ideas, fundamentally encouraged by the U.S. Constitution (Passman, 2019). The value of mimicry is well discussed, but not given due respect in the creative spaces. It is the goal of this article to encourage more academic research and creative discourse around this powerful educational tool in light of this model.

Autonomy. Notwithstanding, creatives arrive at the point where they must develop autonomy of their creative journey through highly complex processes as unique as their individual identities, goals, and interests. Autonomy, then, is informed by other experiences a creative has, and perhaps not necessarily specific to their career goals. Creatives, like other professionals, bring their whole selves to their work, and that expression is unique to their brand. Fans look to see themselves in their favorite artists. In a creative context, creative autonomy is best maximized by one’s engagement in expert facilitation, directly or indirectly. To the extent the creative utilizes tools leading to developed efficiency (via mimicry and expert facilitation) and engage in ways that make their work visible, they have the potential to grow tremendously in their creative and professional goals given the current globalized and highly connected era in which we live. It is in this domain of the model that creatives bring a lot of prior preparation to their journeys, as they look to identify and capitalize on their unique contributions.

Relatedness. With respect to relatedness, the socio-cultural context is important to consider. The ability to be confident in the midst of cultural considerations of effectiveness takes an appreciation for how creatives not only view their own development but also how they measure up in relation to others. The need to have relatedness—be it with peers, fans or the public—is as important as the work done to find one’s own creative identity. To further illustrate, a creative’s contribution that is not critiqued as being relevant might prompt the creative to make changes but only to the extent that it serves the artist. The creative benefits from this experience simply because of proximity to various feedback from different types of music consumers, especially identified experts.

Irrespective of how much investment goes into a project or endeavor, unvalued talent does not monetize well. It is through the practicing of learned skills––in the midst of others––that the creative assesses the relevance of their creative work, and oftentimes to the normalization of failure (Skaggs, 2018). It is still up to the creative to make meaning of these exchanges, internally measuring where they feel their work is relevant to those providing feedback, but also deciding how much work should accompany the feedback. Looking into these three buckets of self-determination theory—relatedness, competence and autonomy—warrants further inquiry into how successful professionals engage creative efficacy, beyond the tools to which they were exposed, or motivated to engage.

Fostering Conviction Through the Process of Creative Efficacy

Finally, to the extent that a creative is able to apply these concepts to their own development, they have the capacity to develop an efficacy that Bandura (1971) asserted as an ability to produce desired effects. Here, it is described as creative conviction. These desired effects result in controlling one’s ability to thrive in a given situation, thus perpetuating the need for continual development (Bandura, 1994). The CET model above shows how these buckets of socio-constructivist development may relate to creatives and their ability to thrive in this context, particularly during a time when creatives are more cognizant of their responsibility in stewarding and monetizing their brand. This conviction consults a need to challenge one’s own abilities versus their creative and professional goals. The 21st century artist is well served to dissect their development in light of their impact on others. In an industry where major music companies already look for evidence of quantifiable success and creative efficacy, the CET provides language that may help further the creative’s ownership of their development.

Recommendations of Practical Application and Research Using the CET

Tools assist us in accomplishing a task. The CET is simply a model used to illustrate important tools creatives engage throughout their artistic journey. While it is without doubt that creatives undergo a process of development as they mature in their craft, it is important to consider that without the opportunity to apply skills the engagement is not fully actualized and thus efficacy may not be achieved. Much of the work in the entertainment industry has the burden of demonstrating its worth. This is no different than the student who learns a foreign language but has no opportunity to practice, yet identical to the student who speaks often but may not communicate fluently, sufficiently or coherently—the exchange of ideas in both scenarios is limited and ineffective. The CET model seeks to share practical implications of best practice among expert and novice creatives, as well as encourage further examination of this phenomenon, with recommendations for future research.

Practical Implications of CET

The difference between a creative’s awareness of their toolbox versus one who effectively engages their toolbox is in their praxis, or the transfer of theory to practice. It is the reconciling of theory and practice that provides optimal opportunities to grow. Every time a creative engages in learning via in the classroom, Internet, YouTube, or in observing expert demonstrations at a concert, conversation or lecture, their ability to use what they learn can become more valuable to others.

From the talented superstars who were trained early in this business––in the case of the Jackson Five, Whitney Houston, the legendary Clark Sisters or Aretha Franklin and countless others to those who very successfully transferred hours of formalized training into a well-regarded brand—there is much to learn from having dialogue and sharing language that demystify these creative processes. The opportunity to connect theory to practice not only gives the academician an opportunity to more deeply engage primary sources in relevant context, but to also provide a rationale for why creatives need to exploit their toolbox with greater efficacy. This is a major practical implication of the CET—fostering the ability to communicate, transfer, and evolve developed practices as we mature and become more complex as a digitally-integrated society.

While there are emerging studies in the entertainment field, many opportunities to bridge gaps exist. The current industry landscape is at the perfect place for the creative to take greater onus of their development; and scholars and practitioners are capitalizing on this need. In the marketplace, successful Do-It-Yourself (DIY) creative and author Ari Herstand (2017) wrote a book, How to Make It in the New Music Business: Practical Tips on Building a Loyal Following and Making a Living as a Musician, helping the creative to thrive in this new era of change. In his text, he highlighted the importance of significant aspects of a creative’s career. The section, How to Master the Internet, underscored the ability and value of mimicking prior models of success, but to the advantage of one leveraging their own fanbase (pp. 323-329). In such a loosely-regulated and highly volatile industry, the bridging of concepts, skills, systems, databases and networks, digital and physical spaces, etc… is the opportunity that creative leaders get to systemize their business and monetize, particularly in formal settings.

As people find themselves communicating between different worlds of creativity and music business, a certain duality begins to maturate. In the creative industries, the ability to exist between two seemingly different worlds is not an altogether strange phenomenon, but perhaps one that is just receiving proper academic discourse. Articles, textbooks, self-help reads, podcasts, interviews, mini-courses and certificates, and other resources abound for creative development. Further, the creative communities are strengthened when access to best practices assists in exploiting relevant creative contributions. The creative must embrace the learning of their craft, but also the business of their craft––this duality is germane to 21st century creatives. Yet this work that creative dualists engage is not just entrepreneurial, but a significant calling to both creative and administrative work and a reckoning of prior boundaries being crossed (Carr, 2019). These naturally-occurring discoveries deserve sustained conversations from the classroom, to the practice room.

Recommendations for Further Research

Due to the lack of research on the process of creative development in this creative context, several opportunities for further research exist at the institutional level. First, one benefit is in exploring and analyzing experts’ developmental and creative processes. Attorney and established industry critic, Bob Lefsetz (2019), described this new, tech-disrupted industry as opportune for artists in many ways. As the industry experiences unprecedented growth in a digitized economy, the ability to learn from the efficacy of creative and administrative industry professionals becomes a valuable form of intellectual capital. Moreover, as the creative industries become more entrepreneurial, it is incumbent upon creative institutions and their faculty to be familiar with a more andragogical approach to understanding one’s craft and the business of their industry. This systemizing of skill development is something that can have lasting engagement in an educational setting, pulling from a myriad of primary sources, and engaging in authentic inquiry.

Accessing and appropriating such a creative toolbox model to creative development gives both individuals and institutions a framework to build curricula, case studies, and critical analyses of the narratives that share similar themes of success or failure. Finally, I would recommend a further study on various domains of the CET, developing an instrument to help explore those critical themes that may exist among various stages of creative identification and development, aiding in the stewarding of creative efficacy to praxis. While it is the intention to provide systems of creative development, it is important to note that this model has the potential to serve both the creative and the facilitator in unpacking and decomposing what makes compelling talent so undeniable. How do experts describe their tools, journeys, failures and experiences in ways that are relatable and teachable? What do we notice about how a novice creative internalizes efficacy versus a veteran creative? Further research exploring these types of questions have the potential to deepen our understanding of how creative professionals express efficacy in light of an identified model of development.

References

Ackerman, C., & Tran, N. (2020). Self-determination theory of motivation: Why intrinsic motivation matters. PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/self-determination-theory/

Atkinson, C. (2011). New Universal Music CEO has star-making plan. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2011/08/28/new-universal-music-ceo-has-star-making-plan/

Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory [PDF]. General Learning Press. http://www.asecib.ase.ro/mps/Bandura_SocialLearningTheory.pdf

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/BanEncy.html

Baskerville, D., & Baskerville, T. (2020). Music business handbook and career guide (12th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Beghetto, R. A., Kaufman, J. C., & Baxter, J. (2011). Answering the unexpected questions: Exploring the relationship between students' creative self-efficacy and teacher ratings of creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5(4), 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022834

Carr, C. (2019). Music business careers (career duality in the creative industries) (1st ed.). Routledge.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health [PDF]. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a32f/3435bb06e362704551cc62c7df3ef2f16ab1.pdf

Gardner, H. (2005). Five minds for the future. Harvard Business Review Press.

Haase, J., Hoff, E. V., Hanel, P. H. P., & Innes-Ker, Å. (2018). A Meta-analysis of the relation between creative self-efficacy and different creativity measurements. Creativity Research Journal, 30(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2018.1411436

Herstand, A. (2017). How to make it in the new music business: Practical tips on building a loyal following and making a living as a musician (1st ed.). Liveright.

Lefsetz, B. (2019). Artists are in control. The Lefsetz Letter. https://lefsetz.com/wordpress/2019/02/18/artists-are-in-control/

Lopez, J. (2020). Junior team grvmnt dances to "dum-dum" by tedashii - world of dance qualifiers 2020 [Video]. NBC World of Dance via YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T70QRRsVWWI

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96. https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm.

McDaniel, R. (2010). Bloom's taxonomy. Vanderbilt University. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Neville, M. (Director). (2013). 20 feet from stardom [Film]. Tremolo Productions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUsdG65neTo

Passman, D. S. (2019). All you need to know about the music business (10th ed.). Simon & Schuster.

Patton, M., Coulter, S., & White, C. (2017). Perceptions of technology-mediated instruction at a southeastern community college [Doctoral dissertation]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Rensin, D. (2003). The mailroom: hollywood history from the bottom up. Ballantine Books.

Skaggs, R. (2019). Socializing rejection and failure in artistic occupational communities. Work and Occupations, 46(2), 149–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888418796546

Stassen, M. (2019). Sir Lucian Grainge: 'No other music company has ever come close to matching what we achieved this year.'. Music Business Worldwide. https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/sir-lucian-grainge-no-other-music-company-has-ever-come-close-to-matching-what-we-achieved-this-year/.

Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1930). http://ouleft.org/wp-content/uploads/Vygotsky-Mind-in-Society.pdf