Abstract

Always the beautiful answer

Who asks a more beautiful question.1Warren Berger, preface to A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014).

-E.E. Cummings

The relationship between composers and conductors has evolved throughout music history. Before the early to mid 1800’s most works were performed as chamber music with the composer leading from within the ensemble. With the growth of musical forces and intricacy of compositional practice, the need for a separate leader at the podium emerged. While early ‘conductors’ were composers themselves, this relationship began to fade as baton technique became its own artistic idiom and conductors approached works with an individual musical perspective. Knowing this, this article asks, “How would one’s knowledge of a musical score deepen if they began to learn the music as though they were composing it?”

Cowritten by a conductor and composer, the authors offer a method for score study that features analytical questions that might not arise from traditional methods, drawing upon the creative insight of the authors and Warren Berger, author of A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas. Though this article focuses on how conductors can become actively engaged with the music they study, the technique described can be used by any musician. To demonstrate this method in practice, the article will feature excerpts from Claude Debussy’s (1862-1918) Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune.

Endnote

1. Warren Berger, preface to A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014).

James A. Grymes

Historical Context

The historical context of conducting in parallel to composition unveils a vast and transformative narrative. While generally viewed today as separate roles, early ‘conductors’ and composers, often referred to as a Kapellmeister, maestro di capella, and maître de musique (Carse 1948, 289, 292), were one and the same, leading not with a baton, but rather from a keyboard or other instrument. Kapellmeisters were considered first and foremost as composers in residence, creating and implementing the musical performances within their establishments of employment (Carse 1948, 289). Music theorist Johann Mattheson (1681-1764) in his Der vollkommene Capellmeister (The Complete Capellmeister) describes such leaders as those deeply trained in the knowledge of “…harmony, counterpoint, orchestration, composition, and the art of singing” (Schuller 1997, 67). Many composers bore this title, including Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), and Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809). While these positions all entailed rehearsing, organizing, and maintaining musical resources for the courts and/or churches, their main responsibility was that of a composer.

As noted above, Kapellmeisters would often lead rehearsals from a keyboard where they could centrally communicate with the ensemble and realize the basso continuo parts. As Baroque music remained fairly consistent in tempo, especially works associated with dance, and was performed by smaller ensembles, composers found their best communication was conveyed as a chamber musician. In contrast to the modern conductor, the task of interpretation was more direct, as the creator and source of the material was usually present.

However, with basso continuo fading out of fashion, by the early 19th century, further reliance on the violinist-leader emerged, especially within France (Carse 1948, 293). Consecutively, the term ‘conductor’ began to be used in connection to this central leader, although still in the broad context of anything from a baton leader, keyboardist, violin-leader, or time-beater, to an influential performer within an ensemble (Carse 1948, 296). Around 1810-1825 a codification of the role began to take shape, as historical writings documented early pioneers of baton technique, including Louis Spohr (1784-1859), Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826), Gaspare Spontini (1774-1851) and young Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) (Carse 1948, 304-305). Even at this stage, however, most if not all ‘conductors’ were also composers.

By the early Romantic era, the complexity of music and the growing size of ensembles tasked composers and conductors with expanding roles. For conductors, this not only included time-beating, but also managing nuances of tempi, ensemble blend and balance, and the rehearsal process itself. With the decrease in courts and chapels and the increase in concert halls and music publishing, composers and conductors began emerging as separate entities, each with their own specialized expertise. Composers began writing in a more individualist fashion creating ‘masterworks’ in need of being preserved and performed on a continual basis. Hector Berlioz’s (1803-1869) essay “On Conducting” (Berlioz and Strauss 1991, 410) included within the Treatise on Instrumentation offers a candid outlook on this divide:

Nobody will accuse an author of conspiring against the success of his own work, and yet there are many composers who unknowingly ruin their best scores because they fancy themselves to be great conductors.

As one of the earliest treatises on the subject, “On Conducting” offers a critical historical context, clearly establishing a separate role between composer and conductor. While many texts following this lineage have been written on conducting and score study, most do not include information concerning the art’s original composer/conductor relationship. Of course, we are not implying that to be a great conductor one must be a great composer (or vice versa), but simply reflecting on an origin that could impact the way one views a score and connects with the music in a deeper way. In the words of Bruno Walter (1961, 24-25):

Now, there is such a thing as reproductive inspiration which compresses the entire, multifarious results of a prolonged study of a work of music by which one approaches a composer, into one spontaneous outpouring. This form of inspiration re-creates, in the specifically interpretive talent to which it is bound, the particular sphere in which the erstwhile creative inspiration had taken place. In this way is born what we may well call an authentic performance. It is only when the creative impulse which has engendered a composition reverberates in every detail of performance, that we can speak of an authentic interpretation.

Survey of Standard Orchestral Conducting/Score Study Techniques

With the distinct division of roles from composer/conductor, the art of score study has become an integral part of a conductor’s preparation. In a survey of materials, we find a plethora of resources on the topic, much of which are beyond the scope of this article.

The following is a brief overview of standard conducting texts and score study techniques used today.

The Conductor’s Score (1985), by Elizabeth A. H. Green and Nicolai Malko, implores one to create an aural conception of the score via a thorough understanding of the work’s instrumentation, phrasing, dynamics, expression, style, etc. In a similar fashion, the well-known The Modern Conductor by Green and Mark Gibson (2004, 3) reflects the teachings of Malko and highlights the use of physical conducting exercises to help establish “a neural pathway from the command in your brain to a specific skill in your hands and wrist.”1Video of Malko Conducting Exercises: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZYFi89Ph4g&t=1283s Known for coining the terms melding and gesture of syncopation, and the use of psychological conducting, the work is a standard collegiate text.

Max Rudolf’s The Grammar of Conducting (1995, 321) offers both technical and interpretational advice for the conductor. In the chapter “Purpose of Score Study,” the following is written: “Studying a score serves a double purpose: to learn the music in terms of notes and markings and to establish a conception of the composition in the broadest sense.” Like The Modern Conductor, Rudolf dedicates several chapters to exploring the physical basics of conducting in addition to helpful commentary on the rehearsal process, memorizing the score, and the collaborative process. Rudolf’s text also provides sections on “Performance Practice” and “Musical Style,” further informing the conductor of artistic choices they will encounter through the study of various works. In Guide to Score Study (1990), authors Frank Battisti and Robert Garofalo give a more systematic approach to learning the score, urging the conductor to analyze both micro and macro details in absorbing a work. This includes a variety of steps within the larger framework of “Score Orientation,” “Score Reading,” “Score Analysis,” and “Score Interpretation.”

Gustav Meier’s The Score, The Orchestra, and The Conductor (2019, 243) opens with an extended chapter entitled “The Beat” discussing the fundamental physical gestures of conducting through the author’s own notational system of diagrams. While not specific to Meier, the text also includes a portion on “The Zigzag Way,” highlighting how the conductor can create a “road map” of decisions based on the focal points of the music throughout a rehearsal/performance. Gunther Schuller’s The Compleat Conductor (1997) and Erich Leinsdorf’s The Composer’s Advocate (1981) focus more on the moral and philosophical responsibility of the conductor, citing the integrity of the score, historical contexts, and specific repertoire examples. These two texts are perhaps the closest to interacting with the score in a way that may lead a conductor to engage with the creative origins of the work.2For other digital sources on score study, Leonard Bernstein’s “How A Great Symphony Was Written” on Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5u1R-OzeSs) and Michael Tilson Thomas’s series Keeping Score (https://michaeltilsonthomas.com/keeping-score/) offer other perspectives on the score study process from a conductor’s point of view.

All of these sources are essential to a conductor’s training and development. However, because not all conductors are composers, the question still remains: are there strategies that can be applied during score study that connect conductors to the original creative process? As conductors, we are always absorbing the score and analyzing its phrases, harmonies, orchestration, and other musical elements, but what if we asked questions connecting us more with a work’s genesis?

A beautiful question is an ambitious yet actionable question that can begin to shift the way we perceive or think about something—and that might serve as a catalyst to bring about change (Berger 2014, 8).

Method and Application

The process of composing is unique to each individual. When seeking insight into a work’s original inspiration, no answers are guaranteed or even certain. The following method is a creative and conversational interaction that uses the art of questioning as a means of investigation and discovery. For our journey, we focus on the questions of why and how, which provide a technique for investigating the various choices made by the composer while writing, rather like Sherlock Holmes making acute observations.

In parallel, Warren Berger (2014, 71, 75) formulates his own technique using the mantra “The Why, What If, and How of Innovative Questioning.” When discussing the why portion of questions that begin his process, he outlines the following steps:

- Step back.

- Notice what others miss.

- Challenge assumptions (including our own).

- Gain a deeper understanding of the situation or problem at hand, through contextual inquiry.

- Question the questions we are asking.

- Take ownership of a particular question.

While these ideas must be adapted to fit the task at hand, the process of investigation and discovery lends well to our method of asking why and how to potentially lead us to revelations and new perspectives. This method can be used at any stage of the score study process, whether absorbing details at a micro or macro level. As mentioned in our survey of score study techniques above, conductors will approach the podium with an informed understanding of a work’s historical context, the composer’s oeuvre, and the central musical aspects of the work itself. In Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (as discussed below), the conductor would also naturally look to the inspirational text by Mallarmé and the music’s connection to symbolism.

All of the above are great examples of where to begin to have a foundational understanding of the work’s context and are valuable elements to share with performers. However, when you follow any of this information with this method’s key question of why or how, you move into the field of conjecture. It is vitally important that any conjecture be relayed to others as such and not as concrete fact. Unless the composer has made a statement to confirm such information, we can never be certain. Phrases such as “maybe”, “perhaps”, “we can’t know for certain”, etc., are our friends. But the guessing and projective thinking do help us understand the music.

By asking why and how, we are looking beyond the surface level and interacting directly with the creative impulse, thus informing our interpretation and actions on the podium. To help categorize these questions, we start with the acronym THOIF.

Thematic Construction—how motives/melodies/rhythms/etc. are manipulated, sustain interest, and relate to other pieces; secondary and background elements’ relationship to primary

Harmony—keys, modulations, harmonic idiom, individual harmonic language, progressions

Orchestration—how the instruments are used (and tessituras, combinations, textures); characteristic or not (to instrument, to genre, to period, to composer)

Instrumentation—literally and as related to the genre (note: instrument refers to vocal as well in this article)

Form—adherence to standard or not, or original/freely composed/having inner logic

*A secondary branch underneath each element is notation.

Asking why with any of the elements listed above can lead to such questions as: why flute and not oboe (Orchestration)? Why the note D and not E (Harmony/Thematic Construction)? Why string orchestra and not full orchestra (Instrumentation/Orchestration)? Why this modality, why this key, why this harmony (Thematic Construction/Harmony)? After asking questions like these, there are follow-up thoughts such as: how does this inform our interpretive choices? Do we need to “do anything about it” or not? Is this element of higher or lower importance, and will it appear again?

When most of the work has been analyzed in this way, we can then ask: how does this inform our knowledge of this composer’s traits? Does it fit into their pattern or is it more of an outlier for them? Does it fit into a pattern of the period’s compositional practice or is it an anomaly (in either “direction”)? How does this composer individualize themself from their contemporaries? Do they reference their own music (or write very similarly to another of their works)? If so, how does that seem to influence the development of their style?

The following interactive dialogue travels through the first few pages of Debussy’s (1983) Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, utilizing this questioning technique as a sample exercise that one may follow with other works. While some score images are used to clarify examples, it is recommended readers open the score and a recording.3Claude Debussy, “Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune”, Three Great Orchestral Works in Full Score, (Mineola: Dover Publications, 1983), accessed January 30, 2021 at https://imslp.org/wiki/Pr%C3%A9lude_%C3%A0_l'apr%C3%A8s-midi_d'un_faune_(Debussy%2C_Claude). Audio recording of Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune for use while analyzing in this article: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y9iDOt2WbjY Throughout the dialogue, reflections on podium applications are included.

Application of questioning method in Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

Study

Moving one page at a time, we look both horizontally and vertically, alternating between macro and micro observations. One can surmise a fair amount from the first pages of a score before looking at notes in detail. First, a harmonic element: there is a key signature, but immediately Debussy uses accidentals. The use of a signature is standard for his time, but we pause to wonder whether there should be a key signature or not, based on how little the work seems to dwell within a diatonic set, at least for this first page. We also mentally note four sharps as a potential indication of any tonal pull. Given that this is an older work, listening to part of a recording and quickly referencing the last page’s final harmony confirms that E major will indeed surface. But the number of accidentals tells us the piece may involve a harmonic struggle of wills.

Podium Impact: The instability of the work’s opening harmonic language could influence the conductor’s nuanced choices for the ebb and flow of tempo. For example, the general chromatic tension would organically drive the music forward. This information would benefit the performers in that looking ahead; after the nebulous opening, R4 stands as an arrival point, with the oboe solo firmly planted in E Major. Debussy gives the instructions of En animant (animating) and dout et expressif (sweet and expressive), perhaps supporting this harmonic shift in character.

The highly chromatic nature of the music could also lead to further connections and possible influence of style. Debussy attended performances of Wagner’s Tristan and Parsifal in 1888-89 and documented how profoundly the experience affected him (Philip 2018, 212). Understanding Debussy’s compositional influences at the time of writing would likely impact a deeper understanding of the work’s chromatic nature, thus lending further insight informing the conductor’s choice of tempo, phrasing, and style.

Study: Instrumentation is the only element that is primarily noted at the beginning of the process, with fewer references throughout unless we are trying to reason why a composer left out a certain instrument or included it. When doing so, this element blends into orchestration. The instrumentation of Prélude is not abnormal for its time, but it is somewhat smaller than the expanded orchestras of Debussy’s contemporaries. To that point, notice that by flipping through the score to glean the instrumentation, there are no trumpets or trombones and very little percussion. Why? Are cylindrical brass too piercing for this music? Or, perhaps, did Debussy originally have them included and decide that they were unnecessary? We could possibly answer the second question with manuscript drafts. The only percussion are antique cymbals, which makes us think that Debussy only uses percussion in a coloristic fashion. The use of two harps also suggests other potential conclusions: 1) Debussy places some special importance on them in this piece, 2) that the tuning system requires two players, or 3) that Debussy could be concerned about their timbre projecting through the ensemble. Most of these suppositions can be at least partially answered through further tracing of their lines within the piece—turning into orchestration matters—and by asking a harpist.

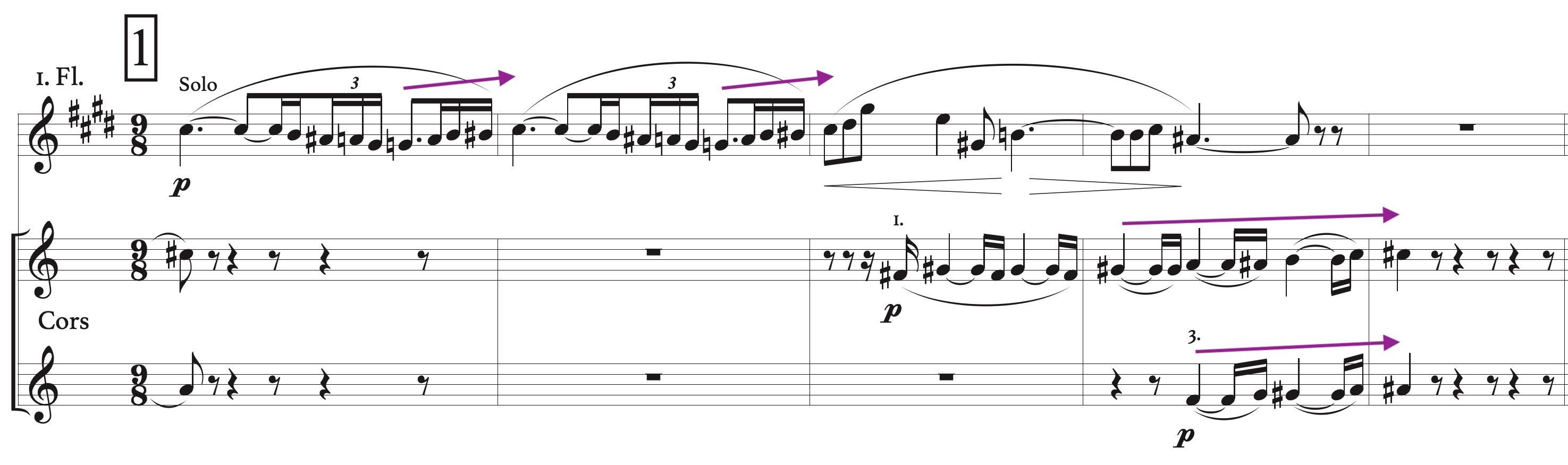

Finally, the notes. Solo flute emerges, with absolutely nothing to support it. How intriguing. Why this orchestration? Some possible reasons include the flute representing the faun; timbre; and/or technical facility. The first can potentially be verified or rejected by reading correspondence or other quoted material from the composer. For the latter two, imagine other instruments playing this line. Bassoon? Quirky, rustic, or perhaps less agile. Trumpet? Could sound like a military or heraldic call (despite the line) and might be less facile. Viola or violin? Might sound less associative given that we hear so much of this timbre in orchestral works. What is it about flute that makes it right for the part? And why this register of the instrument?

Podium Impact: Orchestration can affect the weight of sound that is produced by an orchestra. Noticing that Debussy eliminates brass from the opening few measures of the work will naturally encourage the conductor to create more fluid gestures and tapered phrases from musicians. While the thematic emphasis on flute could naturally be associated with the faun, the act of questioning Debussy’s choice of orchestration leads to further historical research. Several influential French flautists existed during this time, stemming from Paul Taffanel, who could have impacted Debussy’s choice of instrument (Philip 2018, 212). In noticing Debussy’s use of two harps, the conductor is presented with various scenarios as to why; nine measures after Rehearsal 7 is the only location where two players are necessary. According to harpist Gretchen Brumwell,

Two harpists are needed to play all of the notes Debussy wrote in one section (after Rehearsal 7). With two players therefore available, it makes sense that Debussy split the earlier material into two logical parts. Since the texture of the orchestration is quite thin early in the piece, hearing the harp part isn't a problem – so choosing to give both players the same notes to play would be counterproductive (Email message to author, August 21, 2021).

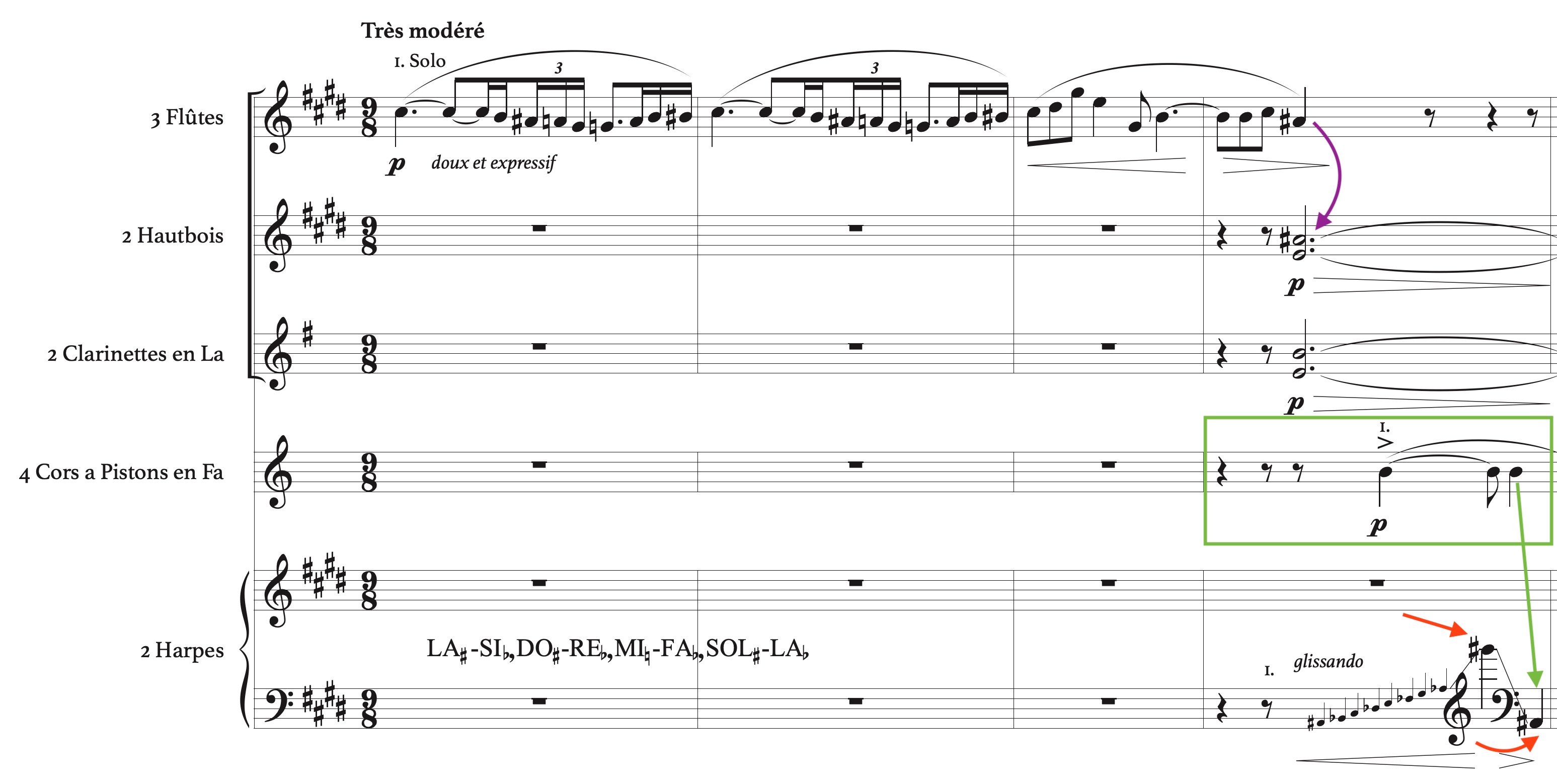

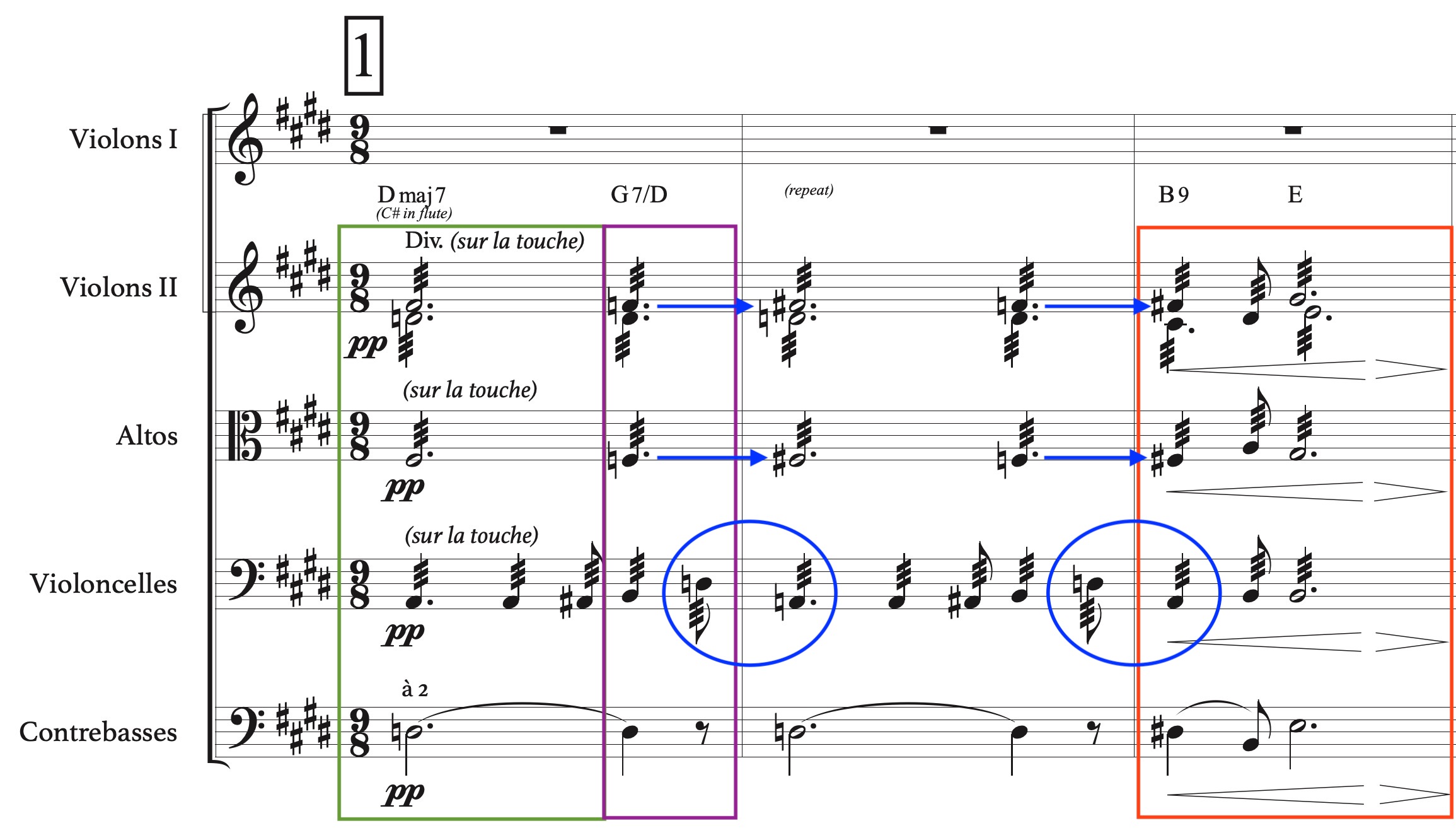

Study: Next, another orchestration element. Notice how the flute line dissolves into the oboes and clarinets (measure 4; Image 1, purple). The dynamic marking of the winds, combined with the doubling of the A-sharp, leads us to believe that a very subtle entrance—one that makes imperceptible the disappearance of the flute—would be a justified request from the podium. This discovery also leads us to see this sustained chord in measure 4 as connected to the melody. Why not have the flute continue in the sustained chord? Two practical possibilities: 1) to give the performer a break to breathe, and/or 2) oboes and clarinets are perhaps a bit better at sustaining harmony. An artistic possibility is timbral shift.

Looking a few staves below, why does the horn come in delayed when it fits into the harmony on beat two (Image 1, green)? (An Orchestration and Harmonic question.) Perhaps Debussy wanted a softer attack on beat two, which continues the melody as determined above; if that, the horn is like a melodic extension. Or, maybe the horn’s delay is used to provide rhythmic rather than harmonic interest. Yet another possibility is that, given the horn’s repeated concert E, Debussy could be foreshadowing the importance of this note by emphasizing it within the chord. Finally, notice that the horn’s second note rhythmically aligns with the harp’s return back from the glissando (though notationally it does not align). Could it be there to assist the harpist, if one is arguing rhythmic accuracy over gestural implication only?

Now, we come to orchestration and notation questions concerning the harp in measure 4 (Image 1, red). The rhythm almost looks like a notational mistake given the meter; but checking the manuscript confirms that it is either intentional or at the very least not a publication error (Debussy 1894). We note that Debussy’s manuscript is quite neat and clear, so it seems unlikely he made consecutive mistakes. The corrected proof on the same IMSLP page also contains no composer’s marks at that moment in the score (Debussy 1895). We then wonder why Debussy notated this way. Is this a rhythmic approximation of an effect, or should the harpist actually follow the rhythm, making each glissandi an eighth note in length? Is this typical harp notation of the period, which a harpist would immediately understand? Or is it an example of innovative rhythm? It is important to follow this thread with a harpist, and if necessary, another conductor and/or authoritative recording. An exact interpretation would require alignment with the horn, whereas effectual performance would not. Also, why one and not both harps? Is it a balance consideration as noted in the Podium Impact section above or concern about aligning that tricky rhythm between two players?

Podium Impact: Conversation again returns Debussy’s use of the harp. The glissando effect nods to Berlioz’s orchestration practices, codifying what would be common practice to later composers. The harp adds to the poem’s dream-like state, adding timbral and harmonic interest throughout the work. Upon closer investigation however, new questions arise. According to William W. Austin,

The instructions for the pedals in the score, cannot be followed literally. They call for nonexistent eighth string in the octave, or else for one string to be in two positions (A in mm. 4-7, B in mm. 90-91). The harpist’s part shows this mistake corrected once, left standing the other time (Debussy 1970, 87).

This question reveals a sophisticated understanding to Debussy’s writing. Once again, consulting with a harpist provides clarity. In reaction to the quote above, Gretchen Brumwell articulates the following:

If you think through the pitches listed for the harp 1 pedal setting at the beginning of the score, you can see that it doesn’t matter whether the A pedal is set to sharp or flat. The pitches listed are A sharp, B flat, C sharp, D flat, E natural, F flat, G sharp, and A flat. So, the first glissando in the harp 1 part actually contains only four pitches: B flat, C sharp, E natural, and G sharp, with the other strings duplicating these pitches enharmonically. The A strings will duplicate the pitch of the B strings if set to sharp or G strings if set to flat (Email message to author, August 23, 2021).

While this information may not directly impact gestural decisions from the podium, it assures us that the score can be played accurately and no further adjustment is needed. When addressing the rhythmic notation of the harp, Brumwell states:

Sometimes a final note at the end of a glissando does indicate rhythmic value, showing the beat on which the glissando ends. Therefore, it is logical to ask whether the final quarter note we see in measure four indicates that the glissando should end on beat 8. However, several factors do not support this:

1) Debussy's use of a quarter note within the glissando to indicate the top of its range leads to the assumption that this final quarter note could also simply indicate the bottom of its range.

2) In the vertical alignment of the score, this quarter note does not align with beat 8; instead, it is placed at the very end of the measure.

3) The rhythmic value of a glissando is often shown by the value of other elements within the measure. The rests preceding the glissando in measure four clearly indicate that it begins on beat 4. Dividing the remaining six beats evenly results in three beats for the ascending glissando and three beats for the descending glissando. This perfectly aligns with the score in both measures four and seven (Email message to the author August 30, 2021).

Information gleaned from talking with a harpist confirms the questioning model at hand; through curiosity, one can gain a deeper understanding of the score and the original intentions of the composer.

Study: Looking down the page, the strings have not entered yet, a somewhat rare instance within orchestral repertoire. We already did our guessing about the flute, but why winds, horn, and harp at measure 4, and not other instruments? The strings could have executed a glissando, albeit with less facility over that range (a reason to use harp!). Why not strings for the sustained harmony? It is hard to find a practical reason for not including part of the string section, so this must be an artistic decision. What does that tell us about their entrance? Does this special focus on select wind instruments continue through the piece, or is it an isolated event?

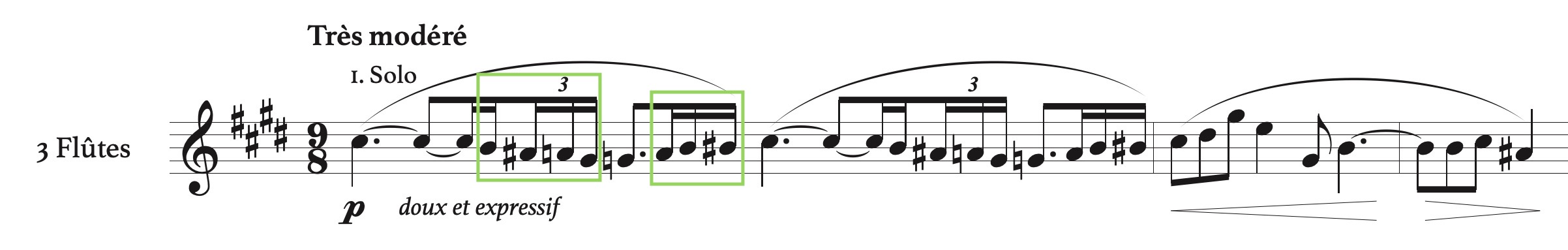

Having examined orchestration, our questions now center on harmonic construction. The flute moves from C-sharp to G and back to C-sharp with nearly-chromatic passing tones between (Image 2, green). Why? When writing, how did Debussy arrive at those passing tones rather than the other options? A few ideas come to mind. First, the chromatic scale may have felt too conclusive or cliché. Second, if the rhythm and anchor notes of C-sharp and G came first, the rhythm does not allow for a chromatic scale ending on G. Or, all of the notes may have been chosen first, and the rhythm was then composed to fit. Thinking gesturally, it has a lazy sensibility that suits the poem’s atmosphere, akin to a sigh or a slow, slumping shrug. Likewise, the pitches, by moving first by whole-step and then into half-steps, indicate an initial reluctance to tension. It is possible that Debussy knew he wanted half-steps moving into the axial notes of C-sharp and G and from there chose the other pitches. Can we know for certain? Probably not, but all of these possibilities and pondering provide critical thinking opportunities for us to more actively engage with the score.

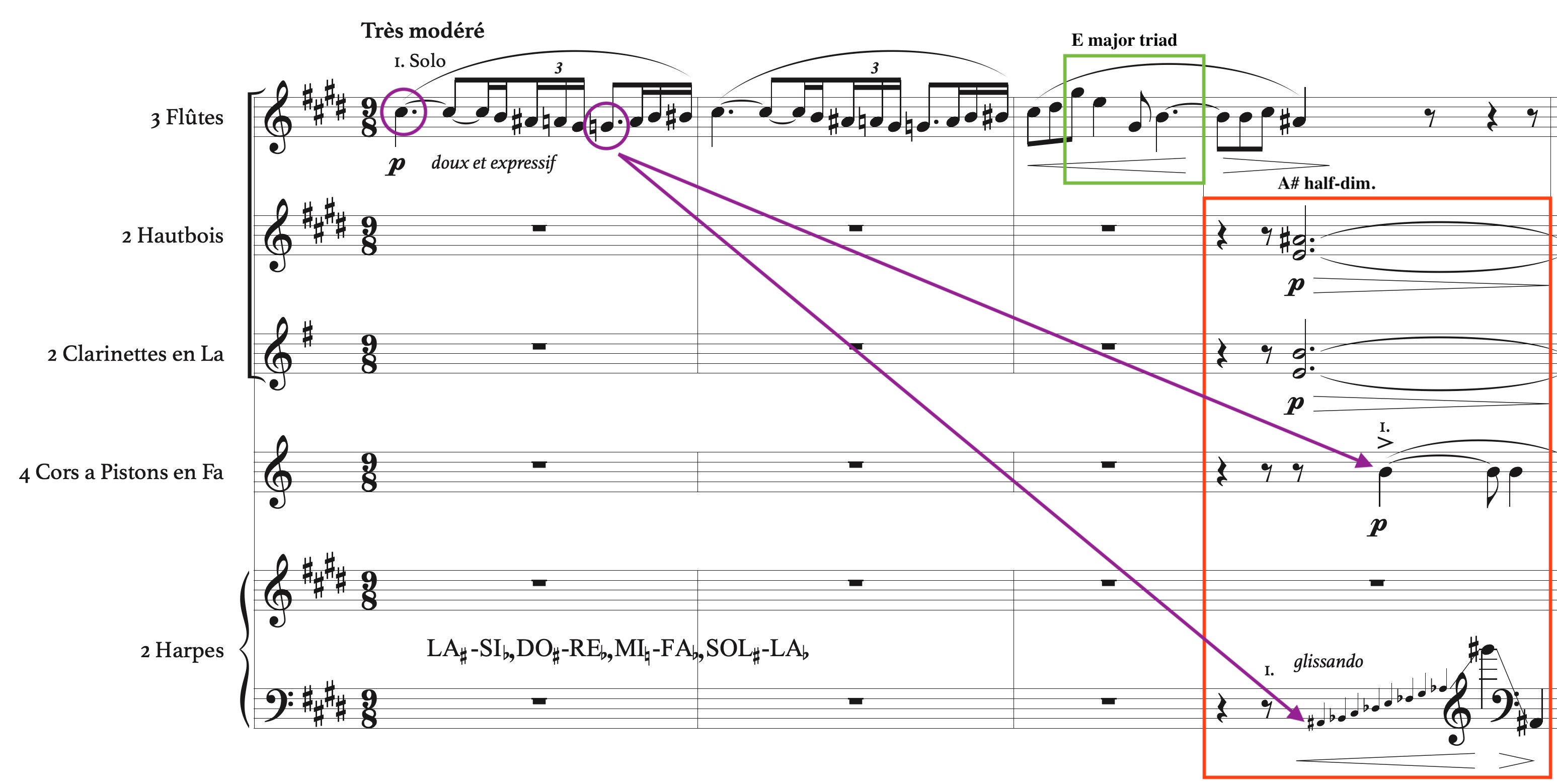

As a harmonic note, in the third measure (Image 3, green), Debussy gives a clear melodic framework in E major—and then he diverts with the harmony in measure 4 of C-sharp, E, G-sharp, and A-sharp (an A-sharp half-diminished sonority in inversion; Image 3, red). Why this harmony, and why step away from E so quickly? This goes back to the initial accidentals—it seems to be another hint at harmonic struggle, or the piece’s unwillingness to commit to a sonority. To our ears, half-diminished chords contain both tension and the sensation of floating; did Debussy choose this particular sonority to avoid clear harmonic direction? This leads us to an additional discovery: a connection between this harmony and the first measure (Image 3, purple). The initial axis was C-sharp and G (a tritone) and the axis of this chord is A-sharp and E (because the A-sharp is the lowest pitch, in the harp, and the E is emphasized in the horn). This repetition suggests importance and that the concept will perhaps reappear later in the score.

Podium Impact: While there are no concrete answers to the questions presented above, they do encourage the conductor to grapple with deeper layers within the work. It is interesting to note that the tritone outlined within the opening flute motive is repeated in a varied fashion throughout the piece: Rehearsal 1, Rehearsal 2, six measures after Rehearsal 2, and Rehearsal 10. Noticing the subtle rhythmic and melodic differences between each of these occurrences provides an opportunity to emphasize this harmonic metamorphosis. Toward the end of the work, the conductor may also notice that Debussy gradually fades this tritone relationship into a perfect fourth. Looking at four measures after Rehearsal 12, the flute sustains the C-sharp while the G-natural is eventually replaced with a G-sharp, creating a sense of subtle resolution to the opening tension. The flute’s last two notes within the work also reflect this observation.

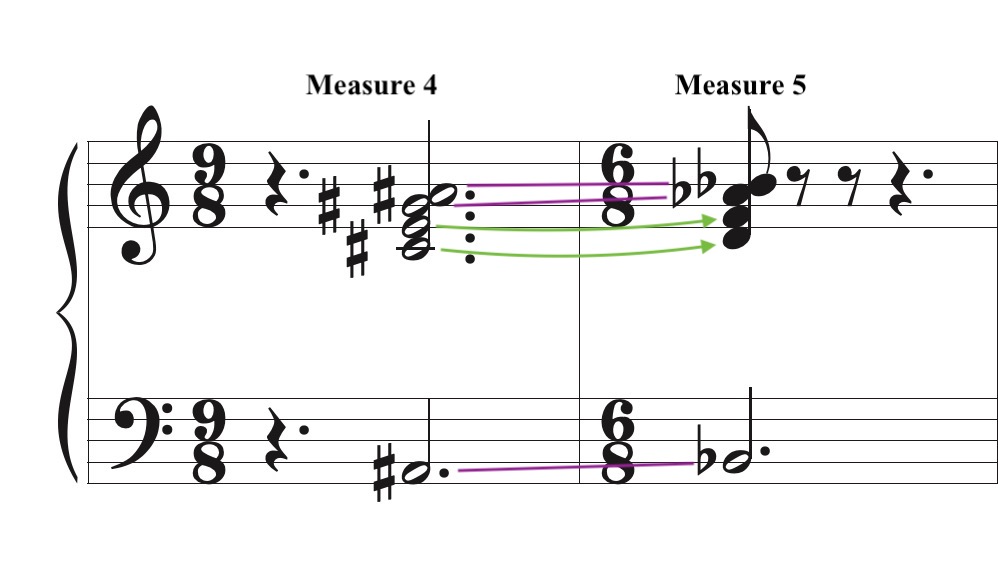

Study: Looking further at the harmony, in measure 5 Debussy gives us a very clear B-flat dominant chord on the downbeat (Image 4). How did we get there from E major? Recall the A-sharps from the previous page, which built the A-sharp half-diminished chord in measure 4. That chord is halfway to a B-flat dominant sonority: it already has B-flat and A-flat, enharmonically. The C-sharp and E need only shift a half-step upward to achieve the new chord.

This manifestation of harmony works in conjunction with Debussy’s use of orchestration. On the new dominant chord Debussy allows strings to enter—but only the lower voices. Material from the second harpist dovetails the first harpist, serving as connective material for the B-flat. Notice that the first horn, previously on E, shifts up to F before continuing its melodic fragment. The oboes and clarinets pull much of the weight, with the second oboe shifting to E-sharp and the first remaining on A-sharp (notational quirks that look better in the performers’ parts). In the same way, the first clarinet remains on the G-sharp and the second moves from C-sharp to D.

Podium Impact: Debussy’s expressive use of harmony allows for stylistic nuances throughout the work. In measure 4, he defies harmonic expectation by arriving at a B-flat dominant chord rather than the expected resolution to B major. With no harmonic expectation now, the lower strings and horns are given the opportunity to linger within their lines and the lush new tonality; the harmony, like the orchestration, is used as an expressive means. As a conductor, these entrances would be conducted with more nuance of energy, serving as connective threads to the work’s opening, rather than a harmonic arrival point.

Study: As it is now apparent that Debussy made the tritone leap from E tonality to B-flat by using pitches from the previous harmony as common and neighboring tones to pivot in a completely unexpected direction, we can examine the why. We find it helpful to deepen our understanding of why and how these creative moments happen by trying the alternatives, as done earlier with the flute’s opening line. In this instance, we imagine or actually play the beginning of Préude up to the A-sharp half-diminished chord, and then resolve it to a B major triad, as that chord “should” do in common practice. Now, it is even clearer to us how Debussy was able to manage the transition and why he may have chosen to do so. Not only does this analysis inform us from a compositional mindset, it also illuminates to us the character of the piece. We can expect more unconventional harmonies, but perhaps in subtle fashions rather than sudden juxtapositions. Looking at measure 5, the horns contain melodic material that seems likely to reoccur. We also might pause to consider whether the horn and flute will dialogue throughout the piece, since this short passage feels like a response to the flute’s opening line. We notice that the horns continue throughout measures 7-10 and that the flute re-enters later in measure 11 (Rehearsal 1).

Going back into detail on the second page, measure 6 is silent, followed by Debussy returning to the A-sharp half-diminished chord in measure 7. This time, there is no transition aside from allowing the air to clear from the previous sonority. Why? He could have had the strings, harp, and horn shift the F and D back downward and kept the B-flat and A-flat (as A-sharp and G-sharp) to make a continuous effect. Instead, there is a rest followed by the upper strings’ first entrance on the half-diminished chord, voiced in the same way and range as the version in the winds in measure 4. A couple of possibilities come to mind: first, formally, the rest gives the sense of an introduction having ended. If we scan a few pages further, we notice there are no other pauses like it; we feel fairly certain this is Debussy’s way of ending the first musical statement. We might go back to the poem to see if there are any specific words or lines that correlate to this rest. Second, our musical taste may hear a second half-step shift as redundant, and perhaps Debussy felt this way too. By giving pause and then allowing new instruments to take our interest, the transition is fresh.

At measure 11 (Rehearsal 1; Image 5, green), the flute melody is identical to the one before, except for the length of its final note. This time Debussy allows the flute to play alongside the oboe for a brief time. Why? Is this an instance of Debussy wanting a new timbral combination, or was he concerned about balancing the oboe entrance against the other voices? Or perhaps this allows for an even smoother transition between the flute and oboe.

The harmony at measure 11 is a shimmery D major seventh chord for beats one and two, and then shifts to a G dominant chord (Image 6, green and purple). The following measure is an exact repeat. How do these harmonies come into play from the previous page? Following the horns, our sole connective voices, We see that one sustains through on concert D, while the other shifts upward to concert F-sharp. This is the first time we have heard F-sharp—the only note left of the twelve notes in the chromatic scale. Is this related to our new key of D major, or incidental? Also, notice the V-I relationship of D to G, slightly denied because of the sevenths involved. It is unsettled yet familiar. Is this what Debussy meant to imply?

Podium Impact: While most standard orchestral works before Debussy’s time used functional harmony to propel the music forward, Debussy’s Prelude relies upon varied repetition in which orchestration and chordal changes defy expectation and add interest and a certain shimmer. Throughout the work, strings are often used as a blanket of sound to generate these harmonic contrasts, serving as complements to the wind interjections above. Emphasizing these shifts of harmony and various timbral changes in the strings helps to propel the music forward and draw the listeners’ ears to Debussy’s expressive harmonic gestures.

Study: At measure 13 (Image 6, red), the B dominant chord in the first beat (considered as a whole beat, not separately) firmly moves to E major on the second beat, presenting the clearest tonal center we have heard thus far. How does he move from G dominant to B dominant? Notice the string and clarinet voice leading—again, Debussy seems to lean on common tones and small voice leading movements to achieve unconventional shifts. While the motion from G to B does not include sustained common tones in this instance, Debussy does utilize familiarity in another way. Clarinet I, the upper part of violin 2, viola, and cello replicate the same movement as the measure before, causing the shift to almost sound like another repeated measure until they continue past the downbeat (Image 6, blue). Every other voice moves by half-step. Is this how Debussy will achieve more harmonic shifts in the piece—by utilizing false repetition to transition elsewhere?

Now looking at thematic material, the horn renews its response to the flute in measure 13 that occurred earlier within the piece (Image 7). In comparison, however, we find some differences: the theme occurs earlier than in the previous statement (refer to Image 3) and is now using the undulating whole-step motive from measure 5. It slithers upward rather like the end of the chromatic part of the flute line (Image 7, purple). Was this an intentional reference or a way to invoke certain harmonies as a means to a destination? Looking for chromatic downward or upward motion moving forward could inform whether it was intentional. As potential confirmation, in measures 14-17 the bass line moves downward in a similar fashion.

Podium Impact: Analyzing the use of horn throughout the work may give subtle clues to Debussy’s relationship with orchestration and form. While it is challenging to concretely divide the work into definitive sections, the horn does seem to play a role in key moments within the piece. This includes creating a connective thread within the work’s opening (measures 21-30) and closing (measures 94-100), in addition to timbral and rhythmic interest within the work’s climax (Debussy 1970, 88).

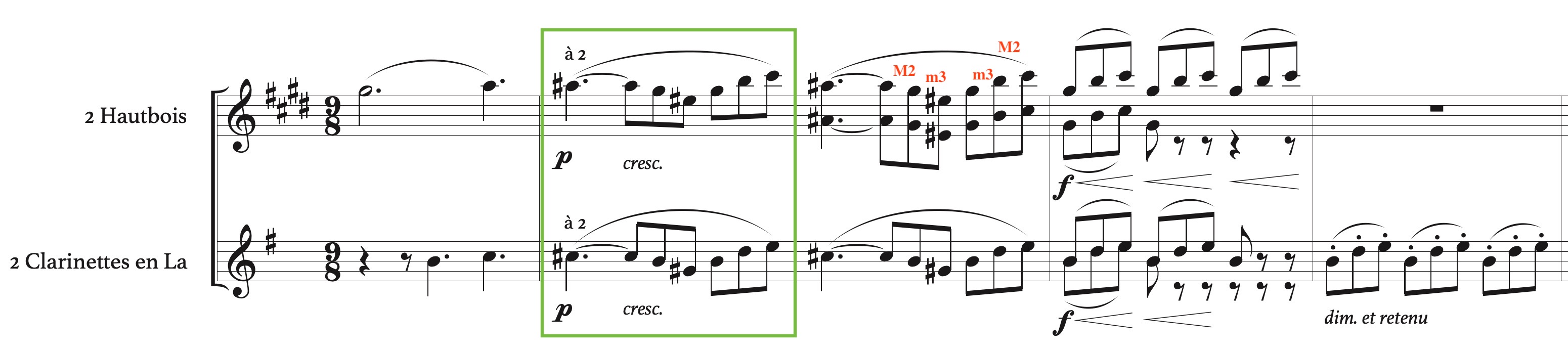

Study: In measure 17, a wave-like pattern appears in the clarinet and oboe (Image 8, green), joined by the first violins in measure 18. Have we seen this particular motive before, aside from it resembling the flute’s chromatic line (reference Image 5)? Viewed separately, the two beats are an inverse of each other (major second, minor third/minor third, major second; Image 8, red). We have seen the whole step before in the third horn in measure 5, and the step-plus-leap is also familiar from the end of the flute line (reference Image 5). Notice how the solo clarinet copies it in measure 20 and then uses a half-step to pivot into the flute line at Rehearsal 2. Having only gotten to the fourth page, a macro question that arises is whether this wave-like undulation will continue through the work, and what that choice in contour could mean about the entire piece. Is it somehow related to the poem as an overarching theme, or this is more of an intuitive decision about melodic material? Either way (if we were able to come to a true answer as stated by Debussy) is legitimate. It is in asking the question that we strengthen and inform our artistic decisions on the podium.

And now, what about the background material? What purpose are the tremolo strings serving, and are there any familiar motives within it? How does Debussy use rests? Who does he use for sustained pitches and why? Despite the music’s luxurious nature, there is surprisingly little time in which Debussy allows complete stillness. Someone is almost always moving within the texture. From this observation, we wonder: how do the melodies and short motives develop without becoming repetitive? How does the background material evolve? How do the harmonies connect with each other in both traditional and non-traditional ways? How does this work compare to Debussy’s other orchestral pieces? Furthermore, what is unique about his orchestration?

After having worked through the entire piece, the analysis would turn toward the formal logic by cross-referencing as needed. After coming to a conclusion about the form, more questions would arise: why this form, if there is an identifiable form? Does it fit completely or partially into a category that will help us to remember or understand it? If so, how does it relate to other examples of the form? Was it premeditated, or was it an organic process as the music unfolded? And again, how does it relate to Debussy’s other works?

Podium Impact: In comparing Debussy’s Prelude to more traditional classical works, we find contrast in our expectations of form, harmony, and melody that can be revealing. The work, like Mallarmé’s poem, creates a continuous stream of sound that is hard to divide into definitive stand-alone sections. Cadences, while present, function more in conjunction with the orchestration and melodic motives than on their own harmonic terms. Investigating Debussy’s melding of these elements reveals his own unique compositional language, perhaps coined “melodic harmonies” (Debussy 1970, 79). Rather than functioning as separate entities, we find that Debussy uses pitches, orchestration, and unorthodox harmonic motion together as a form of expression. As a conductor, this could change the way in which balance and blend are achieved. Thus, rather than balancing the orchestration to merely melodic moments, attention could be drawn to bringing out new orchestral timbres, unique harmonic shifts, and key pitch associations throughout the work. The function of implied cadences could also change, allowing for moments of slight reprieve, rather than definitive sections of closure.

Conclusion

There will always be more questions when analyzing. Knowing the true answer here is less important than asking the question and allowing your mind to critically consider the possibilities, which in turn helps us connect with and better understand the music. Finally, remember the most important words and phrases when conveying your findings to others: maybe, if, perhaps, possibly, etc. While some of the questions result in factual answers (i.e. “The clarinet repeats the motive and then switches to a half-step at the end, which in turn pivots directly into the flute’s C-sharp at Rehearsal 2”), we cannot imply that the composer thought or did things a certain way unless we have proof. Sharing the possibilities with performers is rewarding, however; we all can remember how good it feels to have a conductor tell you the importance of your part, especially when it seems like minutia.

Are we assuming that Debussy composed the way we just analyzed? No. We are looking for possibilities to open our minds to how the creative process may have occurred, which in turn gives us ideas for how to conduct a portion of music. It lends creative perspective about a composer or genre, particularly if patterns develop; it can help distinguish moments of importance that may not be obvious at face-value. This is a process that can be applied to the oldest of manuscripts and the freshest music being written today. We encourage readers from all historical specializations to try the method, even if the piece in question has been analyzed numerous times by other scholars (or yourself!).

As a final note, it is not only conductors, performers, and historians who can benefit from analyzing music in this way. Composers benefit from learning how their predecessors may have thought, and they should always consider how their own scores will be perceived by the conductor or the performer (and when in doubt, just ask them!). Composers, what can you do to best help a performer understand your intentions in the most efficient way possible? Consider what the conductor needs to see and know, both as they study the music and in the moment of conducting. We all have our “blinders” based on our experiences and expertise, though this article hopes to shed light on others’ practices for everyone’s benefit. Step into their shoes and enjoy an alternate perspective. It is actually quite fun.

Notes

1. Video of Malko Conducting Exercises: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZYFi89Ph4g&t=1283s

2. For other digital sources on score study, Leonard Bernstein’s “How A Great Symphony Was Written” on Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5u1R-OzeSs) and Michael Tilson Thomas’s series Keeping Score (https://michaeltilsonthomas.com/keeping-score/) offer other perspectives on the score study process from a conductor’s point of view.

3. Claude Debussy, “Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune”, Three Great Orchestral Works in Full Score, (Mineola: Dover Publications, 1983), accessed January 30, 2021 at https://imslp.org/wiki/Pr%C3%A9lude_%C3%A0_l'apr%C3%A8s-midi_d'un_faune_(Debussy%2C_Claude). Audio recording of Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune for use while analyzing in this article: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y9iDOt2WbjY

References

Battisti, Frank and Robert Garofalo. 1990. Guide to Score Study for the Wind Band Conductor. Ft. Lauderdale, Florida: Meredith Music Publications.

Berger, Warren. 2014. A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas. New York: Bloomsbury.

Berlioz, Hector and Richard Strauss. 1991. Treatise on Instrumentation. New York: Dover Publications.

Carse, Adam. 1948. The Orchestra from Beethoven to Berlioz. New York: Broude Books.

Debussy, Claude. 1983. “Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune.” Three Great Orchestral Works in Full Score. Mineola: Dover Publications. https://imslp.org/wiki/Pr%C3%A9lude_%C3%A0_l%27apr%C3%A8s-midi_d%27un_faune_(Debussy, Claude)

Debussy, Claude. 1970. Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun.” Edited by William W. Austin. New York: W.W Norton & Company.

Debussy, Claude. 1894. Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Holograph manuscript. https://imslp.org/wiki/Pr%C3%A9lude_%C3%A0_l%27apr%C3%A8s-midi_d%27un_faune_(Debussy, Claude)

Debussy, Claude. [1895.] Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Paris: E. Fromont, n.d. https://imslp.org/wiki/Pr%C3%A9lude_%C3%A0_l%27apr%C3%A8s-midi_d%27un_faune_(Debussy, Claude)

Green, Elizabeth A. H. and Mark Gibson. 2004. The Modern Conductor, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Green, Elizabeth A. H, and Nicolai Malko. 1985. The Conductor’s Score. Englewood Cliffs,New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Leinsdorf, Erich. 1981. The Composer’s Advocate: A Radical Orthodoxy for Musicians. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Meier, Gustav. 2019. The Score, The Orchestra, and the Conductor. New York: Oxford University Press.

Philip, Robert. 2018. The Classical Music Lover’s Companion to Orchestral Music. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rudolf, Max. 1995. The Grammar of Conducting. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Group.

Schuller, Gunther. 1997. The Compleat Conductor. New York: Oxford University Press.

Walter, Bruno. 1961. On Music and Music Making. Trans. by Paul Hamburger. New York: W.W Norton & Company.