Abstract

Music careers are in a constant state of flux, and college and university music programs have the arduous task of ensuring that music curricula remain relevant in an ever-changing music career environment. Moreover, college and university music curricula are usually based on traditional or western-European models that some suggest can become stagnant, resulting in a curriculum that stays mostly unchanged for decades. As music careers continue to evolve and music curricula in higher education remain mostly stagnant, the gap between the skills and knowledge students learned in college and those that are required in the contemporary workforce becomes increasingly noticeable. The purpose of this study is, through interviews with early-career professional musicians, to identify recent music careers innovations that may not yet be reflected in the college music curriculum, using a mid-sized regional university in the state of Tennessee as a case study. Interviews were conducted with 20 music alumni who now hold positions as professional musicians. Results suggest that there are many commonalities among music career fields regarding the joys and frustrations that musicians face in their careers. Participants stated that music careers have in fact evolved in recent years and, while some new job functions can be learned on-the-job, there are many aspects of their careers where they felt the university music curriculum may need revision to address the current and projected needs.

James A. Grymes

Music careers are in a constant state of flux as economy, technology and many other factors influence the availability of music careers, how professional musicians function within each music and music-related career, and the requisite skills and knowledge for success as a professional musician. As a result, college and university music programs have the arduous task of ensuring that music curricula remain relevant in an ever-changing music career environment, and preparing students for music careers as they will exist when students graduate and enter the workforce (Campbell, 2014b).

College and university music curricula are usually based on traditional or western-European models that some suggest can become stagnant, resulting in a curriculum that stays mostly unchanged for decades (Campbell et al., 2014; Campbell, 2014b; Larson, 2019). As such, students can graduate with the skills and knowledge that prepare them for a workforce as it existed when the curriculum was established some decades ago. As music careers continue to evolve and music curricula in higher education remain mostly stagnant, the gap between the skills and knowledge students learned in college and those that are required in the contemporary workforce becomes increasingly noticeable (Doyle, 2017).

As such, it is incumbent upon university music programs to ensure that curricular offerings are fluid, addressing the needs of the current and future graduates while also remaining grounded in solid foundations. More specifically, ongoing research is necessary to identify possible gaps between college music curricular offerings and the requisite skills and knowledge that graduates may need upon entering a music career. In addition, while certain aspects of this research may be effective if conducted on a larger scope, it may be equally beneficial to conduct this research on a case-by-case or campus-by-campus basis so that each campus may identify potential areas of needed improvement in its curriculum.

Professional musicians who are in the earlier years of their careers are well suited to assist in this research and aid their alma maters in identifying possible gaps between curriculum and current career needs. Due to their unique positions, early-career alumni will have enough professional experience to know what their careers require, but will also be early enough in their careers that they may likely remember what they learned in college compared to what they learned on-the-job. Therefore, early-career alumni can provide essential information for university music programs seeking to identify possible gaps between curriculum and current music career trends.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is, through interviews with early-career professional musicians, to identify recent music careers innovations that may not yet be reflected in the college music curriculum using a mid-sized regional university in the state of Tennessee as a case study. Information collected from this research may identify areas of needed improvements in the college music curriculum, either in the form of updated courses, new courses, or new concentrations. The research questions that guide this project are:

- In what ways have music careers changed in recent years as reported by professional musicians in each music career field?

- In what ways do professional musicians project future changes to their careers? What evidence supports these speculations?

- Based on the answers to research questions one and two, what changes to collegiate music degree programs, if any, may be needed to prepare the next generation of professional musicians to enter the music workforce?

Review of selected literature

Music careers as a field of research is grossly underrepresented given the breadth of research in other areas of music philosophy, pedagogy, psychology, and performance practice. This lack of music career research may directly contribute to the perceived gap between music career practices and music curriculum in higher education. In contrast, there are numerous commercial publications and online resources, mostly devoted to performance careers or the music industry but these resources discuss the careers apart from curriculum or the professional musicians themselves. In addition, these resources do not attempt to align careers with the curricula or experiences that prepare musicians for their respective careers. Therefore, certain commercial publications and online resources for professional musicians were purposefully excluded from review in this study.

The collegiate music curriculum has been a source of discussion for many years. On one hand, many traditionalists may support that a curriculum based on Western-European music traditions would be stagnate by design as the music itself comes from a historical context. In contrast, other researchers contend that music is a fluid art and must exist relevant to the modern world. In 2014, then CMS president Patricia Shehan Campbell wrote broadly about the need for innovation in college and university music curricula. In this study, she outlined various societal, cultural, technological, and other innovations that have impacted the ways music is studied, taught, and performed. Campbell wrote, “As the world turns, so should our programs of music in higher education dynamically evolve” (para. 3). Although Campbell did write about the need to innovate, she neither described specific innovations in each field of music study, nor connected these innovations to music careers.

With regard to career preparation, there is a similar dialog concerning the differences between a liberal arts degree (BA or BS) in Music, and a professional or baccalaureate degree (Bachelor of Music or BM). In a 2014 study, Levine suggested differences in music curriculum at liberal arts colleges compared to schools of music. Levine argued the curriculum at liberal arts college should focus on making music more relevant to society and culture since many graduates from liberal arts colleges tend to non-musical careers upon graduation. Similarly, a liberal arts college should prepare students for a broad range of life experiences rather than a narrow focus on a particular career. As it relates to the current study, some may then argue that preparing students for a particular music career may be more limiting than intended.

Returning to music careers as a field of research, Talbot provided a brief narrative description of various music careers in a 2013 study. In this article, Talbot described basic functions of each job, statistics pertaining to employability, and connected these careers to music degrees in higher education. A 2010 study by Branscome also sought to identify various music careers, but focused more on the skills, interests and values that make musicians more suitable for one career over another by conducting interviews with professional musicians in each career field (2010). In neither study were curriculum compared to career preparation, nor were participants asked to compare what they learned in college to current career expectations.

Particularly in music education, there are numerous studies that seek to identify desirable traits of music educators, primarily for the sake of identifying these traits in young musicians as a means of recruiting new teachers (Councill, et al., 2013; Rickels, et al., 2013). Similarly, there are various studies that identify the factors that led musicians to their chosen careers (Bergee, et al., 2001; Brand, 2002; Davis, 1990; Gillespie & Hammond, 1999; Thorton & Bergee, 2008; Willcox, 2000). Still, there is a need for research in a broader range of music careers focusing on career readiness and preparation to ensure that future musicians in all music careers are prepared to contribute to the music workforce of tomorrow.

Method

Through interviews with professional musicians, this study sought to identify recent music career innovations that may not yet be reflected in the college music curriculum, using a mid-sized regional university as a case study. After obtaining IRB approval to conduct the study, I acquired a list of music alumni from the Alumni Relations office at the case study university. The parameters for the list included students who had graduated with a Bachelor of Music, a Bachelor of Science, or Bachelor of Arts in Music ranging from five to twenty years prior to the study. The list contained 183 alumni.

To create the survey, I generated a list of questions based on the research questions. Two of the questions were derived from a prior music career study by Branscome (2010). After the survey was created, I emailed the questions to three professional musicians to ask for feedback on the questions. I then conducted a pilot study with five professional musicians to check the reliability of the survey protocol and questions. The survey is included as Appendix A.

To conduct the study, I first sent an email inquiry to all alumni on the list I received from the Alumni Office. Once an alumnus replied, I responded via email to schedule an interview time. All interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom, and each interview took approximately 20 minutes to complete. After two weeks of non-response from an alumnus, I sent a second email to request an interview. After an additional two weeks, I sent one final request for participation in the study. After three email attempts there were 20 alumni who responded and who participated in the study (10.9% of the alumni database). Although this is a lower response rate than desired, the participants reflect the demographic of the current student body with regard to gender, performance medium, degree and career pursuits. The low response rate was due partly to COVID-19 and partly to the fact that the only contact information on file for alumni is the email or phone number that students submitted to the alumni office when they graduated.

Results and Discussion

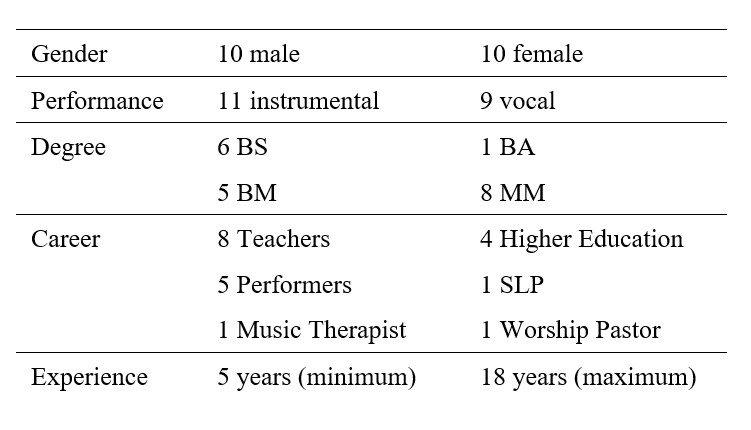

Of the participants, there were ten males (50%) and ten females (50%). No participants identified as non-binary. Eleven alumni were instrumentalists (55%) and nine were vocalists (45%). While most the alumni were enrolled as students, the university offered Bachelor of Science (BS) and Bachelor of Arts (BA) in Music with concentrations in music education, performance, and liberal studies. At the graduate level, the university offered a Master of Music with concentrations in performance, conducting and music education. During the timeframe that these alumni graduated, the music department restructured its curricula to offer music education and performance under the Bachelor of Music (BM) designation while keeping the BA and BS titles for liberal studies. Among the participants, six graduated with a BS (30%), one graduated with a BA (5%), five graduated with a BM (25%), and eight graduated with a Master of Music (MM / 40%). Eight of the participants were K-12 music teachers (40%); four participants worked in higher education (20%); five participants were professional performers (25%); one was a Speech Language Pathologist (5%); one was a music therapist (5%), and one was a worship pastor (5%). Years of experience ranged from five to 18 years with an average of 9.4 years of experience.

Table 1

Demographics

Results are grouped by survey question and usually include three categories: performers; music educators; and miscellaneous (music therapy, speech-language pathologist, and worship music).

Joys or Thrills as a Professional Musician

In the first survey question, participants were asked to describe the common joys or thrills they experience in their respective careers. In response to this question, performers tended to speak most about the act of making music. Specific aspects of this included collaboration in music making, the discovery of learning a new piece, getting on stage to see how people respond to new music, and simply “doing the thing I spent so much time training to do.”

Most responses from music educators tended towards a central theme of interactions with students. Music educators tended to state that they enjoyed being able to contribute to the moment when a student understands something for the first time, masters a new skill, or accomplishes something new. Music educators referred to these moments as the “light bulb” moments, the “a-ha” moments, the “confidence building” moments, and the “conquering moments.” Music educators in this survey also replied that they feel joy when seeing their students be creative in ways they did not know they could, or when their students make breakthroughs in their own musical journeys. An additional theme from music educators in this study was that they feel joy when their students see how much the hard work pays off.

Next, music educators described they felt joy they felt from developing life-long participants in music, helping students find new music, or turning a student on to a new hobby that might stay with them through their entire lives. Finally, music educators felt joy in connecting with their students, sometimes not even about music or curricular content. One respondent stated, “Every day is full of small joys if you look for them.”

The music therapist stated that she finds joy in building relationships with people. The SLP stated that she finds joy in being able to pursue her passion and helping others find their voice. Finally, the worship leader stated that he finds joy in enabling others to engage in their musical gifts. This respondent also stated, “The joy of making music transcends what words can express. It’s a gift and a spiritual experience.”

Most Memorable Experience

In the next survey question, respondents were asked to reflect on their most meaningful or memorable career experience. The primary theme among performers in response to this question was the performers’ first experiences at something new. The military musician cited the pride and sense of accomplishment she felt at her first concert performance as a military musician. Another respondent cited that the first “professional job” was his most memorable experience. Other responses included “my first solo concert and getting to make an emotional connection with an audience member,” and “when my band got its first real gig.” Apart from the theme of “firsts,” performers cited that being able to perform in unique venues or perform unique music can be very memorable. One respondent cited his most memorable moment was when he was selected to participate in a national symposium and his family got to watch him participate in the performance.

Similarly, responses from music educators tended to include the first experiences at something. From music educators, these firsts included the first major production as a new teacher, the first out-of-state trip with students, the first “night of the arts,” the first Veteran’s Day program, and the first time they led their students onto the stage. As a generalization, one respondent stated, “You never forget your first group of students.” Music educators also tended to clarify that these experiences were meaningful to them in getting to see all the logistics come together, all the hard work paying off, and getting to see their students succeed. Finally, one teacher cited her most memorable experience was a lesson that brought so much enjoyment to the students that they gave her a standing ovation at the end of class.

Responses from participants in the final category were similar to the themes observed from performers and educators. The music therapy respondent cited her most memorable moment was watching a hospice patient light-up with fond memory of a song from his childhood that the therapist had just used in a session. The SLP stated her most memorable experience was a large-scale event she coordinated for her clients. The worship pastor cited his most meaningful experience was getting to take his church choir to perform at Carnegie Hall in a group of vocalists from around the country.

Behind the Scenes Aspects of the Jobs

In this survey question, respondents were asked to describe the behind-the-scenes aspects of their jobs, or the parts of their jobs that people outside of the profession may not think about or know about. In response to this question, performers unanimously spoke about the paperwork and logistics of being a professional performer. Within this theme, performers spoke about paperwork, setting up and tearing down equipment, recording promotional videos, marketing themselves as performers, social media, and keeping track of finances and taxes. One respondent stated, “You don’t just show up and perform.” This respondent clarified that it takes a lot of time and energy just to get to the job. The military musician stated that all musicians in military ensembles have an additional duty, typically something administrative or managerial, in addition to performing in the ensemble. As a whole, performing musicians stated they feel it is difficult at times to stay in top musical condition while also completing all of these tasks.

Similarly, responses from music educators tended to focus on logistics and paperwork. One music educator stated she has a constant running checklist in her brain, most of which is not connected to music or to the lessons for the day. Another theme among music educators was planning. Respondents stated that they spend a lot of time planning for upcoming performances, trips and other events. In addition, they spend time planning the lesson as it will appear on the lesson plan, and rehearsing how they will deliver or present the lesson to their classes.

One respondent stated that music educators feel like they spend a lot of time being a psychologist, specifically helping students deal with problems in their personal lives. Another respondent stated that music educators spend a lot of time in lunch duty, hallway duty, bus duty, or other ‘crowd managing’ duties. A respondent who is a band director stated that she spends a lot of time with inventory and instrument repair. Finally, one respondent stated that music education can feel more like a life-style than a job in that weekends are commonly consumed by trips, contests, games, and other events.

In the final category, the music therapist stated that people do not realize how much time a music therapist may spend in the research and diagnosis process of working with clients. An outsider may think that the therapist simply walks into a room with a guitar and starts singing, when in fact, several hours are devoted to selecting music for specific clinical or therapeutic reasons. Similarly, the worship leader stated that he spends a great deal of time staying up-to-date on the newest releases in worship music and selecting music for each upcoming sermon theme.

Common Career Frustrations

Next, participants were asked about the most common career frustrations they have experienced or that someone may expect to experience in their career. While there were commonalities in responses to prior survey questions, responses to this question were quite diverse. The only common responses were, first, that musicians sometimes become frustrated at the amount of time they have to spend on administrative tasks instead of practicing or performing; and second, that professional musicians find it hard to maintain a healthy work-life balance.

Common career frustrations among performers in this survey included the difficulty of finding freelance work or auditions for full-time work as a performer. Performers also stated that they can be easily frustrated with unprepared colleagues or coworkers who come to rehearsals without having learned their part. The military musician stated that there is not a lot of diversity in the types of music that military ensembles perform. Finally, one performer stated, “Sometimes musicians have to be a ‘jack of all trades’ which means you don’t really have time to become really good at one particular thing.”

There were noticeably more common career frustrations among music education participants than performers. Music education participants stated that they were commonly frustrated by administrators who can sometimes be micromanagers, parents who are not invested in their children, or teachers on their campus who do not support the value of music education. Music educators stated they can feel frustrated in being the only musician their campus (or one of very few). They feel frustrated at the constant need to raise money for their programs, and a general lack of resources. Music educators stated they feel frustrated when teachers on their campuses use music as a punishment, keeping students from coming to music classes because they misbehaved elsewhere on campus. Finally, they feel frustrated at times by a constantly quick pace of programs, administrative tasks and students who come and go too quickly.

In the final category, the music therapist stated she felt frustrated at the commonality of people overlooking the therapeutic value of music, perhaps devaluing or trivializing the practice of music therapy. The music therapy respondent stated that people sometimes do not hold music therapy with the same esteem as physical therapy, occupational therapy or other common practices, and because of this, it is sometimes hard to get insurance companies to pay for music therapy services. Finally, the worship pastor who participated in this study stated that he felt frustrated by the feeling that 70% of the job is administration. This participant also stated that he felt a constant need to filter-out negative feedback from people at the church regarding the music in worship services.

Recent Changes to Music Careers

In the next interview question, participants were asked to describe any changes to their careers in recent years. In response to this question, a significant majority of responses centered on the COVID-19 pandemic, the resulting difficulty of finding jobs, and the increase of the use of technology in music careers.

Performers stated that there has been an increase of virtual performances in recent years. Performers also stated that they now play or sing with click-track more frequently than in prior years, suggesting a stronger reliance on technology. One performer stated that there is a greater need to teach outside of one’s comfort zone. The military musician stated that an increasing number of performers have become aware of careers as military musicians in recent years, and as a result, it has become more difficult to find a position in military ensembles. Similarly, the military can now be more selective in its hiring processes than in prior years as there are more people from which to choose. Finally, two performers answered the question not from the standpoint of how the careers have changed, but instead, from the standpoint of how a musician interacts with the career field differently as s/he ages. One vocal performer stated that it is common to explore different aspects of the industry, perhaps shifting from commercial music to art music. Similarly, another vocal performer stated that there are more opportunities for young or emerging artist. Once musicians age-out of these opportunities, they are compelled to find new ways to work and new opportunities to explore.

In response to this survey question, music educators spoke most commonly of the recent impacts of COVID-19 on their careers. Among the more common responses pertaining to COVID-19 included a stronger reliance on technology. Most specifically, music educators reported that they feel a lot of the technology that was introduced because of COVID-19 may likely remain in place when the health crisis subsides. Apart from technology, music educators cited an increasing number of health and safety protocols that were established due to COVID-19 and that may likely remain in the future. Finally, music educators commonly stated that COVID-19 had a significantly negative impact on enrollment in school ensembles, and this impact may be evident for years to come.

Unrelated to COVID-19, music educators commonly spoke of changes pertaining to diversity in recent years. Specifically, they spoke of an increased focus on diversity in curriculum and concert programming. They also spoke of increasing diversity among the students in their classrooms, including a heightened awareness of LGBTQ populations. Similarly, one respondent cited a growing need to help students in areas of their personal lives apart from the music curriculum. Next, music educators cited a far greater level of accountability in recent years. Specifically music educators cited a growing need to articulate standards and communicate those standards to administrators and the parents of their students. Finally, two respondents cited changes in higher education. First, college-level music teachers who previously focused on an applied area now commonly find themselves teaching more musicianship classes such as theory, ear-training and music appreciation. Another higher education respondent cited that it is common for music educators at the collegiate level to see an increase in administrative duties for which no training has been provided with each advancement in rank or title.

In the miscellaneous category, the church musician stated that the speed in which the liturgical repertoire changes has increased significantly in recent years. While places of worship in prior generations would have had a limited liturgy or canon of selected songs, newer generations expect the music to change and for new songs to be introduced on a regular basis. Also in this category, the SLP stated that the populations of people needing services has changed in recent years. Specifically in voice therapy, the respondent stated that it is more common now for clients to have breathing disorders and chronic cough. Finally, the SPL cited an increasing number of transgender and non-binary clients who request services to manage a voice change.

Projected Changes in Music Careers

Next, participants were asked to describe any projected or anticipated changes to their careers in upcoming years. Responses from performers were similar to the information they provided in response to the prior question about recent changes. Specifically, performers stated they project a continued reliance on technology and virtual performances. In addition, performers projected that technology will be more important in the making and recording of music, and also in the entrepreneurism that will be increasingly required of performing musicians in the coming years. In response to the current economy, one performer projected that performing companies may become more reliant on local performers instead of hiring more reputable or notable performers who come at a higher cost. One performer also projected that, by the end of the global pandemic, many professional musicians may have moved on to different careers. The military musician stated that musical expectations will continue to increase as more performers learn about music career options in the military. Finally, several performers stated that an increasingly diverse range of skills may be required in the future; specifically, vocalists may be increasingly required to play an instrument. Similarly, contractors may be more likely to hire musicians who can produce their own demos. In addition, performers may likely see an increasingly common requirement for video submissions in the early rounds of auditioning for orchestras, operas, or other production companies.

When music educators responded to this question, their replies also centered on changes pertaining to COVID-19. Most specifically, music educators stated that they do not foresee virtual learning going away any time soon, and the recently-established reliance on technology remaining in place for the foreseeable future. Similarly, one music educator projected that some schools may allow students to continue learning through virtual means, but may only make music ensembles or other performance-based electives available to on-ground students. One music educator projected that homeschooling may be a lot more prevalent in the future, mostly as a result of the lingering effects of the recent global health pandemic. One music educator projected that teacher in-service and other professional development training may be more readily available through virtual offerings in the future. Finally, one music educator questioned how arts educators might be able to retain high academic and musical standards in the future with so much flexibility in the ways in which courses are offered (online, on ground, and hybrid).

Apart from COVID-19, responses from music educators focused on projected shifts in budgets and curriculum. One music educator remarked that there always seems to be a lingering worry about possible financial cutbacks in the arts. One respondent stated that music educators may likely be expected to teach more classes that do not align with their training or licensure, specifically Response to Intervention (RTI), and other types of tutoring based on standardized testing. Another respondent stated that music education seems to be shifting away from classical music with a growing emphasis on popular music and music from other cultures. One respondent remarked that music educators should expect increasing amounts of accountability in the arts, perhaps mirroring state-wide assessment measures that are currently more common in science, math, and language. Finally, at the collegiate level, a music education respondent stated that students seem to be approaching college and career choices with a lot more scrutiny than in prior generations.

In the miscellaneous category, the SLP stated that careers related to speech therapy may likely require a master’s degree for career entry in the near future. Also in this category, the worship pastor stated that churches will likely see a decline in the use of traditional church choirs. According to this participant, younger adults no longer embrace traditional choirs, and tend to prefer church music that more closely aligns to what they hear on the radio (contemporary Christian music).

Preparing Music Majors for Upcoming Changes in Music Careers

In the next question, participants were asked to describe ways that the university (their alma mater) might better prepare students for upcoming changes in music careers. I included this question in this study, not to highlight any particular program, but instead to identify the types of information that former students may view as important to their early career experiences.

In response to this question, performers tended to reflect on technology, entrepreneurism and diversity. Specifically, most performers stated they wanted to have learned more about how to network, market themselves, negotiate a contract, personal finance and other related aspects of being an independent musician. One respondent cited a need to know how to “bridge the gap” between classical skills and other musical styles. This echoed responses from another respondent who wanted to have experienced more diversity in the solo repertoire and ensemble experiences. Next, performers commonly cited a need to know more about technology as a means of marketing and networking, teaching through virtual means, and as a means of making music. Specifically performers cited a growing need to have knowledge and experiences using digital audio workstations (DAW), and other production or notation software.

Technology was also a common theme among music education participants. Specifically, reflecting on the impact of COVID-19, music educators stated they felt “thoroughly unprepared” for remote teaching. In contrast one music educator stated that the current generation of music education majors has learned through virtual means so it may be better equipped to teach virtually than prior generations of college graduates. As a specific remark about technology, one participant stated, “I haven’t used Finale since I graduated.” The context of this quote is that Finale, Sibelius and other notation software packages are usually a primary focus of university music technology courses, but may not be as necessary in the workforce. Music educators in this survey stated they would have benefitted more from experiences with learning management systems such as Google Classroom, Canvas, or D2L, and from learning about common music classroom technologies (GoReact, Smart Music, etc…). Finally, one music educator cited a need to include more training and experiences in basic sound systems. These findings align with a recent study by Dorfman (2015) who surveyed music educators to determine the importance of technology skills and knowledge among pre-service, early-career, and late-career music teachers. In Dorfman’s study, participants suggested that early-career involvement in technology may encourage teachers to continue learning about technology throughout their careers.

Apart from technology, one music education respondent stated s/he would have benefitted from more piano experience. Another respondent cited a need for basic instrument repair techniques classes for instrumental music education majors. One participant suggested that music education majors would benefit from laboratory teaching experiences earlier in the program, rather than waiting until the junior year. Finally, one participant stated that future generations of music teachers need to be better equipped to teach diverse populations, and address issues of diversity in curriculum and concert programming. As a specific example, this respondent suggested a more prominent focus on band and choral literature of women or minority composers.

Best Music Career Preparation

In the next question, participants were asked to describe the aspects of their undergraduate music program that they felt best prepared them for their careers. Similar to the prior survey question, I included the responses to this question in this report, not to praise or critique a particular university, but to identify the types of information that recent graduates may identify as valuable in preparing them for their chosen careers.

Responses from the performers tended to focus on three central themes. First, participants remarked that faculty were readily available for extra help, tutoring, advice, or other types of assistance outside of regular classroom hours. Second, participants stated that, even though the college is not a top-tier conservatory or R-1 school, they felt that the faculty and program offerings were of really high quality, and significantly contributed to their career preparation. Finally, respondents reflected on the flexibility of the curriculum, and the benefit of the department offering a wide array of courses from which students may select. Apart from these themes, respondents reflected on the benefits of the guest speakers and performers that frequently visited campus and whose presentations contributed to their career development. Finally, one performer cited the high expectations of the applied faculty members, stating that these high expectations at the collegiate level minimized any potential “culture shock” of the expectations of performing careers.

Responses from music education participants were similar to those of performers. First, music educators cited the high expectations of the music faculty, and clarified that they felt as prepared for their careers as their peers who graduated from more prominent colleges. As a specific example, one respondent stated, “There has not been a time that I felt unprepared.” Similarly, music education respondents stated that they appreciated the regular availability of their music faculty members for help and advising outside of regular class time. Next, music education respondents cited that they appreciated the ability to work with real students in their music education methods courses, instead of mock lessons and peer teaching. Music education respondents also appreciated the flexibility of the program. Music education respondents also spoke highly of the opportunities to be involved in music education activities apart from the degree requirements. Finally, music education respondents stated that they felt the department was a place to learn, where they knew it was acceptable to make mistakes, and become a better teacher by learning from those mistakes.

Advice to Aspiring Professional Musicians

In the final interview question, participants were asked to reflect on the advice they might give to a young musician who is considering a music career in their field. I included this research question as an all-encompassing summary question to gather any additional information that early-career music professionals view as important and that may need to be added to higher education curriculum, or that higher education music faculty may consider when advising music majors.

The most common response among performers who participated in this study was a recommendation to learn as much about the behind-the-scenes aspects of one’s chosen profession by shadowing a professional, completing internships, volunteering, or communicating with professionals. Through this, respondents stated that future performers learn that performance is not as glamorous as it may appear, and that a lot of hard work, apart from practicing, is required. As a specific example, one participant stated, “It’s not about the fame… Look beneath the surface to see if you can see yourself in all of the behind-the-scenes aspect of the job.” Similarly, another respondent stated, “Know exactly what you’re getting into. Ask a lot of questions and do your research. It is a big commitment.”

Next, performers tended suggest the importance of “having a plan.” Specifically, one respondent stated, “Nothing can be certain but try to have some form of plan so you’re not sent out with a diploma and a ‘good luck.’” Similarly, many performance respondents stated the importance of keeping options open. Specific suggestions included, “Always think about the broader picture; how your skills can translate to things you have not previously considered,” and, “The person you are trying to become and the skills you’re developing may not be ideal for every situation. There are so many interesting situations that, if you’re open to them, can be the beautiful, wonderful possibilities you never would have anticipated.”

Additionally, performers cited the importance of strong correspondence and communication skills, suggesting that correspondence is essential for any profession, but especially for performs for whom professional networking is so important. Finally, one respondent cited the importance of being prepared to hear “no” a lot. This respondent stated, “You get 10 ‘no’s’ for every one ‘yes.’ Don’t let it discourage you. Keep trying.” Similarly, another respondent stated, “Sometimes you have to step away from the stuff that is crippling, and expect yourself to rise to the occasion.”

The most common suggestion among music educators was to get as much experience as possible in many areas of music and the arts. Specifically, one respondent stated, “Look for opportunities where you don’t expect to find them. If you find nothing useful, you’re not listening hard enough. Everything in the periphery may end up in your job.” In stark contrast to this, one respondent suggested it is more important to specialize and become really good at one particular aspect of music or music education.

A second common recommendation from music education respondents pertained to maintaining a positive attitude in a career that can be difficult at times. One respondent stated, “If you can make it through your first year, you can make it through anything.” A second respondent echoed, “Find your enjoyment through your students.” A third respondent stated, “Look for what brings you joy, and don’t let anyone steal it. That is how you burn out.” Finally, one respondent stated, “You need to love it, and love working with people.” Similar to this theme, one respondent stated that a positive attitude is important, not only for one’s own mental health, but also in how a teacher and the teacher’s content area are perceived by the students. Specifically, the respondent stated, “People will remember more about how they felt when they left your class than what you said to them.”

A third recommendation echoed by many music education respondents was to keep one’s options open. It is common for music educators to begin college thinking they may want to teach in a particular area, but for those interests to change over the course of a four to five-year degree program. It is also common for a music education graduate to accept a music teaching position outside of his/her comfort zone when no other jobs are available. As such, respondents stated that it is important to be ready for any type of opportunity. Specifically, one respondent stated that music education majors should pick a secondary instrument/voice other than the “comfort zone instrument.” Another respondent stated, “The more content knowledge you have, the better you’re going to be.” Finally, one respondent stated, “You don’t know what you don’t know.”

Apart from these themes, one music education respondent cited the importance of being proficient at the piano. Another respondent stated that future music educators, especially instrumentalists, need to learn to be a great vocal model. Another respondent suggested that it is important for music education majors to perform as much as possible, and get accustomed to being on stage. Finally, one respondent cited the importance of knowing how to succeed in a job interview. Specifically, this respondent stated, “When you interview, remember that it’s reciprocal. If you don’t feel comfortable somewhere, it is OK to move on.”

Implications

When asked to describe the joys they experience in their careers, nearly all participants reflected on the joy they feel through interacting with people. For performers, this interaction was through connecting with audience members or other ensemble members through collaborative music making, while music educators tended to focus more on interactions in an educational context. Most specifically, music education respondents connected through empowering people, teaching students a new skill, or observing the “lightbulb moments” where students succeeded at a task the first time. Some may find this surprising as performers tend to spend a majority of their professional time in the solitude of the practice room. It may be for this very reason that performers so highly value the small amount of time they have on stage to connect with their audiences. Or, perhaps this finding relates to the element of hard work paying off that participants also described. The hard work takes place in isolation in the practice room, and the culmination of that work is on stage or in front of the class.

The primary implication in this finding is that prospective musicians may need to evaluate the level to which they enjoy personal interactions through music, and specifically, how they enjoy those interactions, either through connecting as performers, or touching someone’s life through an educational experience. This finding should not imply that prospective musicians need to be extraverted in their social lives, but should suggest that musicians in performance and education fields more commonly find joy through person-to-person interactions. Future research may explore the extent to which this finding may or may not apply to music careers such as musicology or composition where more of the professional duties take place in isolation rather than through connection with people.

Regarding participants’ most memorable experiences, respondents in all categories tended to reflect upon either their first experience at something, or their first success with a large-scale task. For most performers, it was their first performance as a professional musician, or their first significant performance. For most music educators, respondents tended to reflect on a first trip with students to a festival, a first large-scale production, or a first group of students. This finding aligns with prior research, specifically citing that musicians feel rewarded or valued in seeing hard work pay off, and this first experience, whatever it may be, is usually the initial culmination of years of hard work (Branscome, 2010). Future research may explore the extent to which this finding may apply to other music careers, particularly those where there may not be an initial large-scale project or product. In addition, future research may seek to identify aspects of their careers where musicians find joy apart from the initial or first-year successes.

The most commonly cited behind-the-scenes aspect of music careers, as reported by participants in this study directly aligned with the most commonly cited career frustration. In all music career categories included in this study, participants cited that the most common behind-the-scenes aspects of their jobs were paperwork and business-oriented tasks that were also the most frustrating parts of their jobs. Respondents in this study stated that they spend a great deal of their time budgeting, networking, filing, managing equipment, and other clerical tasks, and that these duties, while essential to the entrepreneurialism of being a musician, detracted from the time they felt they should be making music, either through performing or through teaching. For music educators, the only variation in this finding was that, instead of independent entrepreneurial tasks, teachers stated they spent excessive time planning and preparing lessons and upcoming programs. This finding leads to a number of implications for higher education and for future research.

On one hand, college music majors may need to maximize the amount of practice time they have while in college because, according to respondents in this survey, there is not always suitable amount of practice time for professional musicians. This suggests that, at least in some music careers, there is not much time to develop one’s own musicianship after graduation from a college program, and therefore, practice time is of utmost importance for college music students. In contrast, some may argue that time may be better spent preparing for the entrepreneurial concepts, business skills, and other logistical elements that are common in music careers, but may not be reflected in collegiate music training programs. According to Larson (2017), these changes are already in place at some institutions, but it may take some time for colleges to catch-up to the quickly changing trends of the music industry. Similarly, Bennett (2017) states, “Employable music graduates of the future may find themselves in any number of different, unpredictable musical situations” (p. 239).

There are two considerations in this suggestion. First, participants in this study were from a singular university that, until recently, did not include entrepreneurialism in its curriculum. Second, entrepreneurialism is a newer trend and participants in this survey graduated before related courses were added to the curriculum. Future research may explore the extent to which entrepreneurialism remains a vital component of music careers and how it may be more thoroughly embedded in higher education music curricula.

Among music educators and the music therapist that participated in this study, there was an additional common theme in response to the most common career frustrations. Respondents stated that they became frustrated when people devalued music, their roles as professional musicians, or the role that music plays in an otherwise non-musical endeavor. In music education, respondents stated it is common to find colleagues who do not uphold music with the same regard or importance as other curricular subjects. In addition, music education respondents cited frustration when co-teachers or administrators use music class as a consequence or as leverage to elicit improved behavior or academic performance from students (e.g. a student who does not improve his/her behavior will be prohibited from attending music class). In music therapy and speech therapy, respondents felt devalued that coworkers did not commonly see the value of music as a therapeutic service. Similarly, the therapists in this study stated that some insurance companies do not cover music therapy or voice therapy because they do not view music as a therapeutic tool. In both categories, respondents cited a general misunderstanding regarding the professional rigor of a music career and the commonality among some to view music merely as a hobby or avocational pursuit. Perhaps the perception of music being devalued is limited to the participants in this study, or perhaps the mindset permeates careers wherein musicians work on a regular basis with non-musicians, such as music education and music therapy. Although there are extensive advocacy groups and philosophical platforms supporting music in various career fields, future research may explore the extent to which these efforts are visible or impactful to people who are not professional musicians. Specific questions may include the extent to which people are aware of music advocacy campaigns and philosophical beliefs about the importance of music, and to what extent do non-musicians agree with or support these statements.

Next, there were two questions about change in the current study: One question asking about recent changes, and a second question asking about projected or future changes. Although this study was not related to COVID-19 and the global health crisis of 2020, due to the timing of the survey, a majority of the respondents remarked about changes to their careers based on COVID-19. Although many of the changes cited by respondents were temporary, there were some responses that participants projected would remain in their respective careers for years to come. Most specifically, participants in all careers represented in this study projected that the newer reliance on technology for both music production and music education would not go away in the near future. In music education, teachers may likely continue to rely heavily on learning management systems and virtual teaching methods. In other careers as well as in music education, musicians may likely continue relying on technology for many aspects of creating, performing, recording and transmitting new music as well as for the business and marketing aspects of music careers. Future research will need to track the continued use of technology in all aspects of music careers, particularly in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, collegiate music programs will need to continue tracking current trends in technology to ensure music curricula in higher education are relevant to the current need.

Another common response among all participants regarding recent and projected changes was that of increased diversity. First, participants cited that music itself is becoming more diverse and that the lines that previously separated music genres have become more blurred in recent years. Similarly, all musicians cited an increase in the diversity of music they are expected to know, teach, or be able to perform. This finding aligns with a study by Larson (2019) who cited a growing need for colleges and universities to expand beyond the traditional band-choir-orchestra model to enhance the career preparation of music educators who will increasingly need to be more knowledgeable in popular music styles. In addition to musical diversity, participants cited increasing diversity among the types of people they reach through music. According to participants in this study, audiences for classical music are becoming more diverse, as are school populations and the demographic of people requesting therapeutic services (music therapy, voice therapy, etc…). Future research is needed in this area to ensure that music curricula in higher education prepare the next generation of music professionals to address the increasing diversity, both in terms of music, and in terms of people. Most specifically, most higher education music curricula are based on music of western-European tradition (Campbell, 2014; Doyle, 2017) and future research may need to track the effectiveness of this model when music careers may require a more diverse background in the future. In addition, music training programs may need to research means to combat regionalism, and ensure college graduates are prepared to interact with people who may not reflect the demographics of the population that immediately surrounds the college campus.

Finally, there were three concluding themes or reflections that, while they did not relate to a specific interview question, do have direct implications for this study. First, in response to several of the survey questions, participants spoke frequently about the open-endedness of their careers, and the need to be open to change; ready and prepared for anything. More directly, among participants in this study, it is common for musicians either to study one specific area of music but to land in a music or music-related career that is different than the original interest. Similarly, it is common for professional roles or duties to change within a specific music career as a musician progresses or advances up the career ladder. In the second scenario, it seemed common among respondents that each advance up the music career ladder resulted in being one step farther away from the actual art of making music. Among the music education respondents, specifically at the collegiate level, respondents typically began their careers as adjunct faculty or at the instructor rank where nearly all of their professional duties included teaching or making music. However, as these faculty progressed in rank, they commonly achieved an administrative position of some kind and became administrators more than musicians. Similarly, when participants pursued careers outside their scope of initial interest, or when they achieved promotion of some kind, they reported that they were commonly asked to fulfill tasks for which they had received no prior training. Future research may seek to identify the extent to which the observations from the current study may or may not exist across the music career spectrum through interviews with musicians in a variety of music career fields who are nearing the end of their careers.

A second observation among all participants is the tendency among professional musicians to spend large amounts of time fulfilling administrative or clerical duties. Frequently respondents spoke about the time they spent planning, completing paperwork, networking, marketing, writing and many other responsibilities apart from practicing or performing. This finding aligns with prior research and the commonality of musicians to either hold multiple jobs or to have multiple responsibilities within one music career (Branscome, 2010; Larson, 2019). In the current study, one participant stated, “You can’t just be good at your instrument or voice. You have to know and be good at the paperwork or you won’t get the jobs.” Future research may seek to identify the amount of time musicians spend making music compared to administrative or clerical requirements to ensure future generations of musicians are prepared to enter the workforce.

Finally, the interview with the military musician provided additional insight into careers as military musicians that, while not directly related to the research questions, did pertain to music career development. According to the participant, military ensembles functions as a microcosm of the music industry at large. According to the participant, all members of a military ensemble also perform a secondary function including music librarian, tour or road manager, instrument repair technicians, and many other opportunities. Through these duties, each musician receives on-the-job training and experience that could likely lead to a secondary music career upon retiring from the military. Future research may analyze the music practices of military ensembles as a possible model for preparing future musicians for entry into a wide array of music careers.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to obtain information about recent music career developments from early-career professional musicians that might inform higher education about possible needed changes to curriculum and practice in music programs in colleges and universities. Responses from interview participants suggested that, while there may be aspects of music careers that have remained stable in recent years, there are also many elements that have changed and are projected to continue doing so. Similarly, responses suggest that although there are myriad music career options, there are commonalities of experiences and evidences of like-mindedness that may permeate musicians across the music career landscape. Finally, although the results of this study reflect the opinions and experiences of the graduates of one university, their reflections may serve as a starting point for ongoing research across higher education to ensure that college and university music programs prepare students to be leaders in the music careers of tomorrow.

References

Albright, D. (2019, July 23). Benchmarking average session duration: What it means and how to improve it. Databox. https://databox.com/average-session-duration-benchmark#definition

Anderson, D. S. (2016). A mandate for higher education. In D. S. Anderson (Ed.), Wellness issues for higher education (pp. 1-15). Routledge.

Bennett, J. (2017). Towards a framework for creativity in popular music degrees. The Routledge Research Companion to Popular Music Education, 285-297. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.4324/9781315613444-23

Bergee, M., Coffman, D., Demorest, S. et al. (2001). Influences on collegiate students’ decisions to become music educator. Report to the National Executive Board of the National Association for Music Education (MENC). Retrieved October 12, 2020, from http://www.menc.org/networks/mc/Bergee-Report.html

Brand, M. (2002). The love of music is not enough. Music Educators Journal, 88(5), 45-53. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.2307/3399825

Branscome, E. (2019). Music career opportunities and career compatibility: Interviews with university music faculty members and professional musicians (3417736). [Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Campbell, P. S. et al., (2014). Transforming music study from its foundations: A manifesto for progressive change in the undergraduate preparation of music majors. The College Music Society. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from https://www.music.org/pdf/pubs/tfumm/TFUMM.pdf

Campbell, P. S. (2014b). Music in higher education: Evolution now and ahead of us. College Music Symposium, 54, http://dx.doi.org/10.18177/sym.2014.54.fr.10554

Councill, K., Brewer, W., Burrack, F., & Juchniewicz, J. (2013). Collegiate connections: Developing the next generation of music teachers: Sample music education association programs that promote the profession and prepare future colleagues. Music Educators Journal, 100(1), 45-49.

Doyle, K. (2017). Low brow to high brow and the entertainment industry. Arts & International Affairs, 2(2). http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.18278/aia.2.2.7

Davis, G. I. (1990). A study of factors related to career choices of high school senior honor band students in Nebraska. Dissertation Abstracts International 52(03), 838.

Dorfman, J. (2015). Perceived importance of technology skills and conceptual understandings for pre-service, early- and late-career music teachers. The College Music Symposium, 55. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.18177/sym.2015.55.itm.10861

Gillespie, R., & Hamann, D. L. (1999). Career choice among string music education students in American colleges and universities. Journal of Research in Music Education, 47(3), 266-278. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.2307/3345784

Larson, R. (2019). Popular music in higher education. College Music Symposium, 59(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.18177/sym.2019.59.sr.11456

Levine, V.L. (2014). Making the music major relevant at liberal arts colleges. College Music Symposium, 54. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.18177/sym.2014.54.fr.10672

Rickels, D. A., Councill, K. H., Fredrickson, W. E., Hairston, M. J., Porter, A. M., & Schmidt, M. (2009). Influences on career choice among music education audition candidates. Journal of Research in Music Education, 57(4), 292-307. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1177/0022429409350779

Talbot, C. (2013) The changing face of music as career. College Music Symposium, 53. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.18177/sym.2013.53.fr.9813

Thorton, L., & Bergee, M. (2008). Career choice influences among music education students at major schools of music. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 117, 7-17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40319448

Willcox, E. (2000). Recruiting for the profession. Teaching Music, 8(2), 48-50.

Appendices

School of Music Sample Descriptive Information

Interview Questions

1. Briefly describe what you do as a ______________________ (teacher, performer, conductor, etc…).

2. What are the joys or thrills you experience as a [career]?

3. Can you share a particular career event or experience that was most memorable?

4. What are some of the behind-the-scenes aspects of your job? Or the parts of your job that people might not think about from the outside looking in?

5. What are some of the common career frustrations you have experienced or might experience as a [career]?

6. A few questions about change:

• In what ways has your job as a [career] changed over the past few years?

• [and] in what ways do you see the career field changing in the near future?

• In what way might APSU better prepare students for upcoming change?

7. What aspect of your time at APSU best prepared you for your career?

8. What advice would you give to a young musician who is thinking about becoming a [career]?