Abstract

The appropriation of musical climax as an act of subversion became a common claim in feminist analysis of music by women composers. The focus on the tension and release in Western classical music has been called out as overtly masculine and even violent. This article investigates claims that perceived differences in Alma Mahler’s musical climax are gendered and subversive. To do so, it identifies where the climaxes fall in Alma Mahler’s published songs, considers the musical climaxes in relation to textual climaxes, and compares these to the climaxes in the contemporaneous work of her composition teacher Alexander Zemlinsky. It argues that normalizing forces of genre, canon, and tradition are evident in Mahler’s Lieder and that divergences from these norms are expressive rather than subversive.

James A. Grymes

“Shot Into the Air Like a Rocket”: Climax in the Lieder of Alma Mahler

Had a dreadful night. Not a wink of sleep until 7:00 a.m.—just creepy dream-visions. Initially, I must admit it was rather fun. I was playing Z[emlinsky] one of my piano pieces. It began softly and came to a wonderful climax, shot into the air like a rocket. But suddenly the music stopped—I saw only the arc of the sheaf and the dripping balls of fire. What an after-glow...1 Alma Mahler-Werfel, Diaries 1898–1902 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000), 372–3.

The appropriation of musical climax as an act of subversion has become a recurring claim in feminist analyses of music by women composers. Goal-oriented narratives of tonal classical music imply a linear and teleological development; this focus on the tension and release of climax has been called out by feminist music scholars, most notably Susan McClary, as overtly masculine and even violent.2 Susan McClary, Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002). Some scholars have argued that when women composers approach musical climax differently than their male counterparts, it is based on gender-specific differences, or differences in sexual experience, and is inherently subversive.3Claims based on essentialist notions of binary gender have admittedly not aged well, but it is nonetheless important to contend with ideas set forth in what have become classic texts, such as those by Susan McClary. See also Ellie Hisama, Gendering Musical Modernism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001) and Sally Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002). In this paper, I will examine various theories of musical climax, particularly as they can be applied to the Lieder of Alma Mahler.

Identifying Musical Climax

Identifying where climaxes fall in musical works is subjective and based on the interaction of various musical, textual, and performative factors. Although some feminist scholarship has privileged structural and harmonic aspects of climax—those related to the denial and/or arrival at a long delayed tonal center—my approach aims to be more inclusive. I explore climax through the perspective of the score, the performer, the listener, and the literary text, as to not value one perspective to the exclusion of others. Austin T. Patty discusses listener experience of climax highlighting how “elements of harmony, melody, rhythm, and various musical parameters such as dynamic level and melodic register interact with one another and the expressive implications of those interactions.”4Austin T. Patty, “Pacing Scenarios: How Harmonic Rhythm and Melodic Pacing Influence our Experience of Musical Climax,” Music Theory Spectrum 31, no. 2 (2009): 325–67, at 366, https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2009.31.2.325. All of these characteristics do indeed play a role in the musical climaxes of Mahler’s Lieder.

In Mahler Lieder, climaxes most often have the following characteristics:

- an ascending vocal line, often climaxing on the highest pitch;

- an increasing dynamic intensity, frequently climaxing in the loudest section;

- an increasing textural density in the piano accompaniment;

- increasing movement—not necessarily faster, but also not harmonically stagnant; and

- harmonic resolution, from tension to release, or, occasionally, an increasing harmonic tension.

The role of harmony in climax is especially complex; Ji Yeon Lee evokes V. Kofi Agawu to argue that:

Where dynamics and pitch are straightforward as highpoint parameters, harmony is treated with great flexibility; rather than entailing a fixed harmonic quality, the primary harmonic mechanism for a given highpoint is whether it achieves the highest harmonic tension or releases it. On the one hand, maximum dissonance produces great tension at the moment of its occurrence due to its functional instability, corresponding to what Agawu classifies as “a point of extreme tension” (2008, 61). On the other hand, a decisive harmonic resolution can produce a highpoint through its cathartic effect, which is then carried over into abatement as the aftermath of that release. This type of highpoint falls into Agawu’s “site of a decisive release of tension.”5 Ji Yeon Lee, “Climax Building in Verismo Opera: Archetype and Variants,” Music Theory Online 26, no. 2 (2020): [2.7], https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.2.8.; Kofi Agawu, Music as Discourse: Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

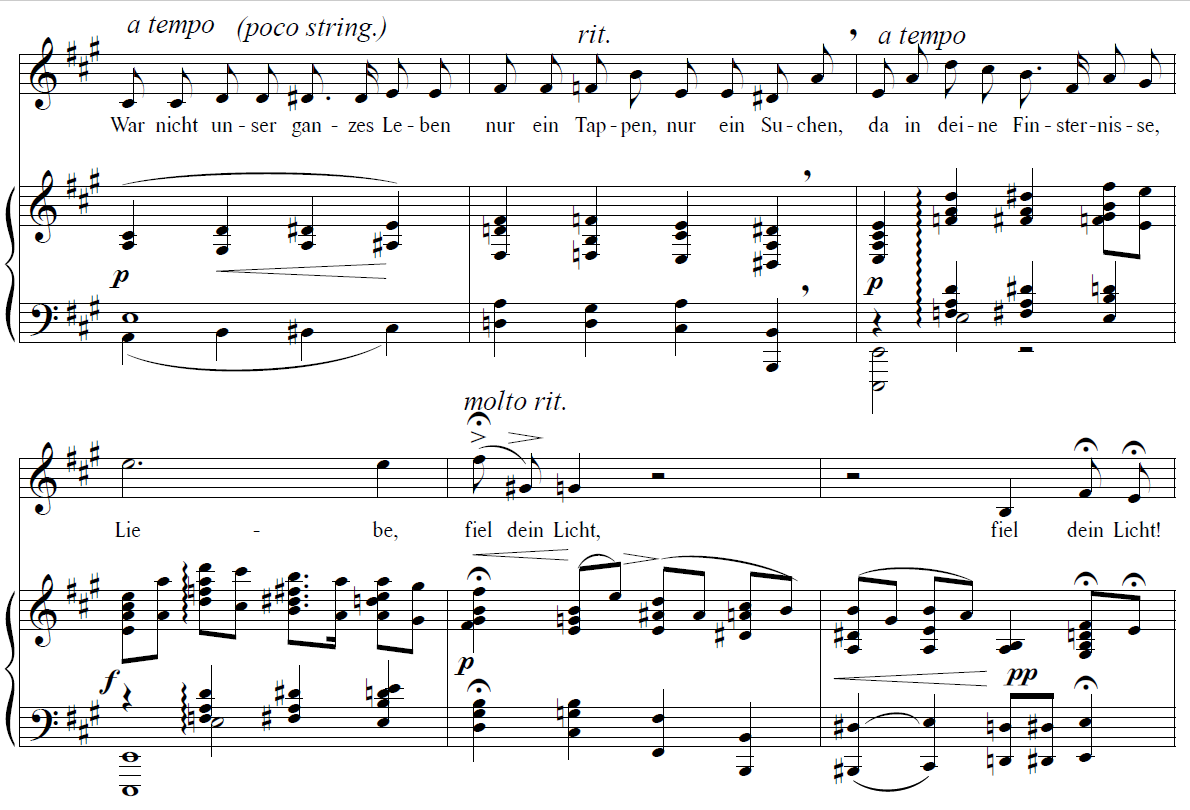

Example 1 provides an excerpt from Mahler’s song “Laue Sommernacht,” from Fünf Lieder (1910). In this piece, for example, the climax falls in measure 19 of 22 total measures. The third of the poem’s three stanzas begins in measure 15, with a piano dynamic marking. The first two measures of the stanza feature a relatively sparse piano accompaniment, with four notes sounding for every chord in measure 15 and five notes for every chord in measure 16. In measures 17 and 18, the presence of thicker harmonies—with six or seven notes sounding in every chord in 17 and seven or eight notes sounding in 18—as well as relatively more quickly moving harmonies increase the textural density of the piano accompaniment. The range of notes in the accompaniment also expands considerably from measure 15 and 18, with A2 to C4 on the downbeat of 15 and E1 to D6 in measure 18.6The range is indicated using the Scientific Pitch Notation system in which C4 refers to middle-C on the keyboard. This increasing movement shows unprecedented direction and need of resolution, even though harmonic resolution does not arrive until after the climax.

The ascending vocal figure in measure 17 (E4, A4, D5) had occurred twice before in the piece, but had previously always resolved downward and led to a measure of rest in the vocal line. In this case, the E, A, D figure resolves downward, but instead of resting the vocal line climbs to a sustained E. In measure 18, the accompaniment is marked with forte dynamics, which combined with the expansive range of the accompaniment and the rolled chords, makes for a dramatic build up to the downbeat of measure 19. Measures 18 and 19 also represent the textual highlight of the song; after searching in the dark night, love’s light fell. The first beat of the vocal line in measure 19 is an F#5, which is the highest note in the vocal line (and in the entire piece). A falling gesture, from F♯5 to G♯4, on the text “fiel” is supported by an accompaniment that also pulls back after the climax.

Example 1. Mahler, “Laue Sommernacht,” measures 15–20, Sämtliche Lieder: für Singstimme und Klavier (Vienna: Universal Editions, [1984]).

Interpreting Musical Climax

Discussions of climax in the work of male composers active in the Romantic era do not frame climax as subversive or redemptive.7Much of the scholarship on climax in Romantic music focuses on large-scale instrumental works and opera—genres from which nineteenth-century women were largely excluded and genres that are admittedly radically different than Lieder. Recent analysis of Gustav Mahler’s “overwhelming” symphonic climaxes and “releases of musical-expressive energy that overspill conventional boundaries” link these to mass appeal and seeking approval from lay audiences.8Peter Franklin, “Mahler’s Overwhelming Climaxes: The Symphony as Mass Medium,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 15, no. 3 (2018): 391–404. Richard Strauss is responsible for the “monstrosity of Salome’s sexual and chromatic transgressions…[by which] extreme violence seems justified – even demanded – for the sake of social and tonal order.”9McClary, Feminine Endings, 100. Hugh MacDonald notes a “volcanic temper” with a climax that “seeks and finds its own violent resolution in Franz Schubert’s instrumental music.”10Hugh MacDonald, “Schubert’s Volcanic Temper,” The Musical Times 119, no. 1629 (1978): 949–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/960118. Verismo opera composers create “violent vocal outbursts, heavy orchestration, big unison climaxes, [and] agitated duets.”11Matteo Sansone, “Verismo,” in Grove Music Online, last modified January 20, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.29210 Richard Wagner evoked language of violence (“violent efforts to find the rupture”) to describe his long-delayed and overwrought climaxes.12Laurence Dreyfus, Wagner and the Erotic Impulse (Harvard University Press, 2012), 104.

Scholars often characterize late-tonal musical climaxes as aggressive and excessive in size, not frequency. Indeed, techniques for delaying climax may contribute to their aggressiveness when finally achieved. Even if climax is a cheap compositional trick executed to emotionally engage listeners and secure a wide base of appeal, it is nonetheless an important part of late nineteenth-century music composition and listener expectation. Kofi Agawu indicates that “the phenomenon of climax is central to our musical experience. In no other repertoire is this more evident than that of the nineteenth century.”13V. Kofi Agawu, “Structural ‘Highpoints’ in Schumann’s Dichterliebe,” Music Analysis 3, no 2 (1984): 159, https://doi.org/10.2307/854315. Agawu establishes the need formulate the experience of highpoints into an analytical model, which he does in this study—coupled with Schenkerian analysis—and in a subsequent monograph. Agawu, Music as Discourse.

In her discussion of canon formation, Marcia Citron discusses the predictive and normative functions of musical genres.14Marcia J. Citron, Gender and the Musical Canon (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 124–7. Compositions that challenge genre norms may not be performed or studied as frequently and can accordingly be devalued; accordingly, subverting listener expectations and genre norms can have profound implications for the initial reception and ongoing performance of Western classical music. To apply this to Alma Mahler’s songs, one might ask what would become of a romantic-era, through-composed Lied with no climax. Listener expectations and genre norms exert a centripetal force on composers of Lieder, compelling them to stay within the bounds.15Mikhail Bakhtin, Dialogic Imagination (Austin, University of Texas Press, 1981), 425: “These are respectively the centralizing and decentralizing (or decentering) forces in any language or culture. The rulers and the high poetic genres of any era exercise a centripetal—a homogenizing and hierarchicizing—influence; the centrifugal (decrowning, dispersing) forces of the clown, mimic and rogue create alternative ‘degraded’ genres down below.”

When the application of feminist theory to musical analysis proliferated in the 1990s, investigating gendered aspects of climax in the music of women composers became a common analytical approach.16Gendering music and musical form extends much further back and has a history of one-dimensional readings and strong reactions, as documented by Scott Burnham, “A. B. Marx and the Gendering of Sonata Form” in Sounding Values: Selected Essays (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2017), 55–78. L. Poundie Burstein, for example, cited the work of feminist literary theorists Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar to inform his comparison of Clara Schumann’s song settings to those of her male contemporaries. Looking specifically at climax in “Er ist gekommen,” Burstein asserts: “Schumann’s setting, with its emphasis on the narrator’s emotions, is more aggressive, more assertively sensuous and erotic. Schumann’s song is certainly not ladylike, but it is profoundly feminine.”17L. Poundie Burstein, “Their Paths, Her Ways: Comparison of Text Settings by Clara Schumann and Other Composers,” Women & Music 6 (2002): 11–28, 24–25. Burstein demonstrates how Schumann used climax to express her understanding of the text; though he suggests that her boldness in letting women characters “speak with their own voices” may be attributed to Schumann’s defiance or naïveté, he does not ascribe intention—subversive or otherwise—to her musical choices.

Differences in composing climax have at times been attributed to an intention to subvert a dominant and masculine climactic ideal. Ellie Hisama has argued that Ruth Crawford Seeger subverted expectations for climax by building cyclical degrees of twist into the third movement of her 1931 String Quartet.18Hisama, Gendering Musical Modernism. Despite the composer’s presentation of a traditional climax, Hisama shows how it was undermined by a cyclical weaving effect created by voice-crossings and timbral displacements, which she measured and analyzed using “twist tool,” and permutations. In discussing the conflict of the traditional climax and subversive weaving in light of “double-voiced discourse,”19The term double-voiced discourse originated in the work of Bakhtin, Dialogic Imagination, 324: “It serves two speakers at the same time and expresses simultaneously two different intentions: the direct intention of the character who is speaking, and the refracted intention of the author. In such discourse there are two voices, two meanings, and two expressions.” Elaine Showalter was among the first to apply “double-voiced discourse” and argues that women’s work “always embodies the social, literary, and cultural heritages of both the muted and the dominant.” Elaine Showalter, “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness,” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 2 (1981): 201, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343159. Hisama compellingly reconciles biographical and musical analysis to document how dominant and muted interact in this particular work of Ruth Crawford Seeger.

McClary discusses Janika Vandervelde’s piano trio Genesis II to consider a successful musical alternative to goal-oriented narratives that build over time, increasing in urgency, until finally, in a “spasm of ejaculatory release,” they recede, fulfilled and exhausted.20McClary, Feminine Endings, 112. Vandervelde’s work includes minimalistic patterns that are repeated cyclically, creating a mechanistic effect. The listener, according to McClary, has no expectation for change or traditional narrative development. This is because Vandervelde “is aware that many of her inherited musical gestures are phallic, for she consistently puts them into contexts that cause them to reveal themselves as such.”21McClary, Feminine Endings, 124. This begs the question of whether male-identifying minimalist composers also contend with the sexism of inherited gestures when they compose stylistically similar music. The evidence suggests that Steve Reich, as an example, espoused phase shifting and other rule-determined processes not out of an awareness of or desire to expose phallic forms but rather because they allowed him to compose “seamless, continuous, uninterrupted” music.22Erik Christensen categorized compositional processes as rule-determined, goal-directed, or indeterminate and identified Reich’s Piano Phase (1966) as a model of rule-determined processes that are bound by parameters established by the composer. This is in contrast to goal-directed processes, which are not governed by adherence to rules but are rather an “audible realization of the composer’s vision of the form.” Erik Christensen, “Overt and Hidden Processes in 20th Century Music,” in Process Theories: Crossdisciplinary Studies in Dynamic Categories, ed. Johanna Seibt, 97–117 (Kluwer, 2003), 107. Reich describes the appeal thusly: “This process struck me as a way of going through a number of relationships between two identities without ever having any transitions. It was a seamless, continuous, uninterrupted musical process.” Reich, Writings About Music (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974), 50.

Sally Macarthur brings feminist analysis to the music of women composers to explore their tendency “to deal with the structural elements of the music in ways that are different from those of male composers.”23Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 178. She leverages the golden section to investigate the placement of musical climax and the proportional lengths of musical sections. Macarthur finds that climaxes are in unexpected places in selected works by Rebecca Clarke, Elisabeth Lutyens, and Alma Mahler, for example, and suggests that “a female composer, inhabiting a female body, conceives of her musical proportions differently than does a male composer” and “avoids creating those proportions that are idealized in musical form.”24Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 96.

Settings of “Ansturm” by Mahler and Zemlinsky

Richard Dehmel’s poem “Ansturm” was published in the late nineteenth century and set by composers including Alma Mahler and Alexander Zemlinsky. Mahler’s setting of was likely written in 1911 and was published in Vier Lieder (1915).25Alma Maria Mahler-Werfel, Vier Lieder (Vienna: Universal, 1915). Susan Filler dates Mahler songs published in 1915 based on dates in the initial publication and on manuscripts in the collection of Henry Louis de la Grange. Susan M. Filler, Gustav and Alma Mahler: A Research and Information Guide (London: Taylor & Francis, 2012), 30. Zemlinsky’s setting was composed in 1907 but which was not published until after his death in 1942.26Alexander Zemlinsky, Lieder aus dem Nachlass: Gesang und Klavier, ed. Antony Beaumont (Munich: Ricordi, 1995), 15. The text and translation, provided below, support a sexual reading and setting.

Ansturm (Richard Dehmel)27Richard Dehmel, “Ansturm” in Erlösungen: Gedichte und Sprüche (Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler, 1898), 136.

O zürne nicht, wenn mein Begehren

dunkel aus seinen Grenzen bricht,

soll es uns selber nicht verzehren,

muß es heraus! ans Licht! ans Licht!

Fühlst ja, wie all mein Innres brandet,

und wenn herauf der Aufruhr bricht,

jäh über deinen Frieden strandet,

dann bebst du—aber du zürnst mir nicht.

Onslaught28All translations provided by the author.

Oh, do not be angry if my desire

darkly breaks out of its bounds,

If it shall not consume us,

it must come out into light! into light! into light!

You feel how my insides surge,

and when the tumult breaks out,

abruptly washing over your peace,

you quiver—but are not angry with me.

Macarthur compares the settings of “Ansturm” by Mahler and Zemlinsky to discuss gendered differences in sexual identity and voice. Macarthur argues that Mahler departs from compositional norms and ideals by climaxing early, where Zemlinsky reinforces them by climaxing approximately two-thirds of the way through the song and posits, “It is possible to view Schindler-Mahler’s music in terms of difference based on the particularities of her sex.”29Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 69.

Macarthur uses the divine ratio to frame her discussion on the timing of climax: “What we find with the divine ratio is that the climax tends to be positioned around two-thirds of the way through the music (or at the proportion 0.618). This corresponds to a stereotypical idea of male sexual experience in which erection and penetration leading to climax take longer than the aftermath leading to closure.”30Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 70. She suggests that music theorists have used divine ratio to avoid “thinking about music’s connectedness to the human body and to bodily behaviors” and argues that such studies privilege and perpetuate classical music produced by men because of their alignment with stereotypical representations of male sexual desire and release.31Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 70. I agree with Macarthur that studies employing golden section have largely perpetuated “great masterworks from the canon” (70). While the divine ratio may be helpful for understanding climax in the sonata form, where the return to tonic is expected around two-thirds of the way through the movement, in the case of turn-of-the-century Lieder climax is too dependent on the interaction of a variety of musical, textual, and performative elements to comply with a rigid and idealized ratio. Female sexual release would not, per Macarthur’s metaphor, correspond to the golden mean.

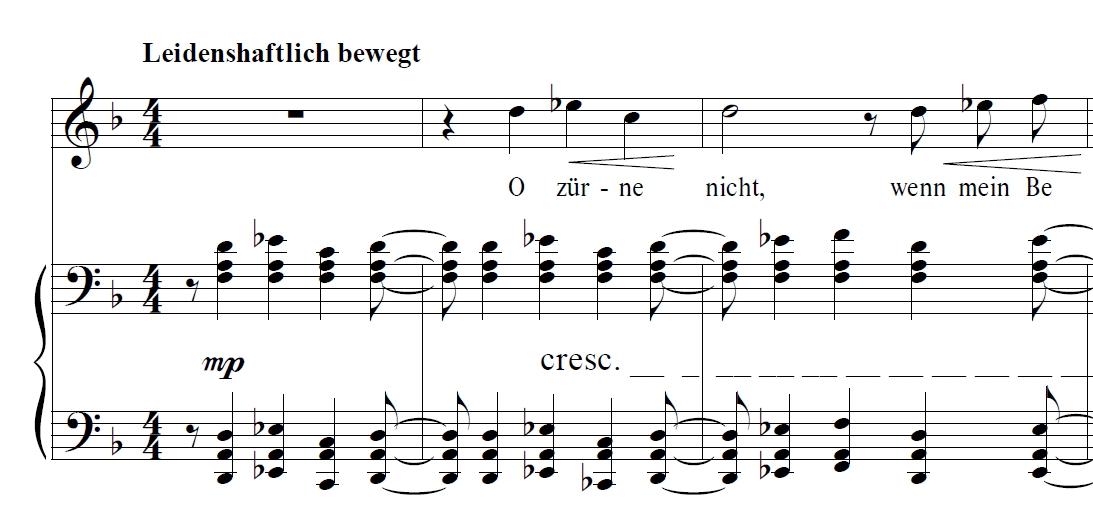

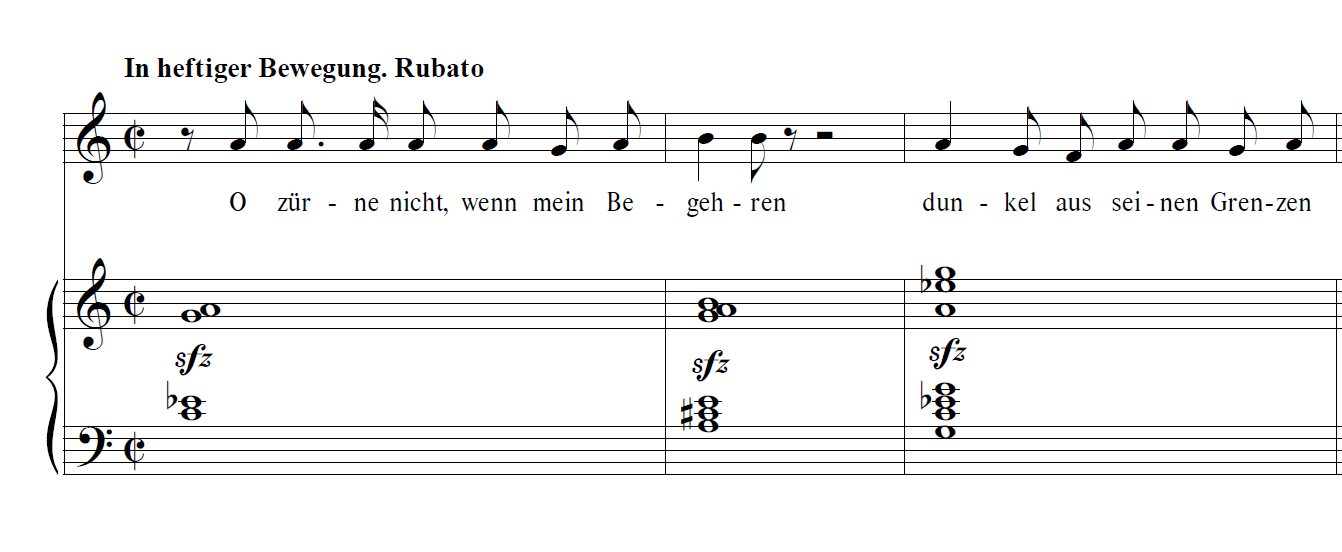

Macarthur argues that Mahler’s setting was a response to her former teacher Zemlinsky’s setting. Specifically, Macarthur suggests that Mahler appropriates and “radically transforms” Zemlinsky’s opening accompaniment figure.32Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 76: “The opening accompaniment figure in the piano part of the Zemlinsky setting is appropriated by Alma Schindler-Mahler for the voice part.” The opening statements shown in Examples 2 and 3 are drastically different, but I have not found evidence indicating that Mahler was familiar with or responding to Zemlinsky’s setting. The persona in the Zemlinsky’s setting seems more constant, and Mahler’s more variable. For example, Zemlinsky sets the opening text “O zürne nicht, wenn mein Begehren” in the higher part of the vocal range with an assured and sustained vocal line that demands that the listener not be angry. Mahler’s conversational, rubato opening entreats the listener not to be angry, and almost sounds explanatory. This could easily be understood as gendered; he demands, and she entreats.

Example 2. Zemlinsky, “Ansturm,” measures 1–3, Lieder aus dem Nachlass: Gesang und Klavier (Munich: Ricordi, 1995). © Universal Music – MGB Songs on behalf of G. Ricordi & Co., Buehnen Musikverlag GmbH.

Example 3. Mahler, “Ansturm,” measures 1–3, Sämtliche Lieder: für Singstimme und Klavier (Vienna: Universal Editions, [1984]).

Both songs make extensive use of chromaticism and have lush harmonic sonorities.33Zemlinsky’s setting is in D minor and ends in D major. If considered with respect to the “tragic to triumphant” archetype, Zemlinsky’s minor to major shift might suggest a change of state that is gendered male in its triumphant closure. Robert Hatten, “On Narrativity in Music: Expressive Genres and Levels of Discourse in Beethoven,” Indiana Theory Review 12 (1991): 75–98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24045351. Macarthur argues that Mahler’s setting is much more harmonically adventurous than is Zemlinsky’s; an example of this is that Mahler resists compositional norms by closing on a “highly unstable feeling” V7 and not the tonic.34Macarthur, “The Power of Sound, The Power of Sex,” 74. Macarthur’s argument linking harmonic closure to subversiveness has more potential than arguments surrounding climax. Mahler avoided closure in multiple songs; this pattern of flouting genre conventions and user expectation may be interpreted as intentional and yield a more fruitful discussion of subversion. I would want this argument reconciled with Mahler’s extensive use of nonfunctional harmony for the expectation of harmonic closure. Macarthur acknowledged that “the composer avoids establishing a key or key center for the song and uses nonfunctional harmony extensively, thus indicating a move in the direction of atonality” at 73. However, the text ends (“du zürnst mir nicht”) as it began (“O zürne nicht”), and where Zemlinsky demands at the beginning and assumes at the end, Mahler’s less insistent and conclusive approach on both counts could also be read as gendered—a desire for consent and unwillingness to assume—but likely not subversive.

Macarthur indicates that by composing a climax that falls before divine ratio, Mahler is “representing passionate love from a female perspective.”35Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 74. Similarly, she suggests, Zemlinsky represents—or at least does not question—traditional and masculine representations of erotic love. Macarthur refers to McClary’s analysis of Vandervelde’s Jack and the Beanstalk,36Susan McClary most famously discusses gendered aspects of music theory, including cadence and closure, in Feminine Endings. and Elizabeth Sayrs’s interpretation thereof, to discuss gendered representations of desire and release: “Representations of male desire and release are regularly discussed in terms of erection-penetration-climax-closure.”37 Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 70; Elizabeth Sayrs, “Deconstructing McClary: Narrative, Feminine Sexuality, and Feminism in Susan McClary’s Feminine Endings,” College Music Symposium 33/34 (1993/1994): 41–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374248. Those of women, Macarthur asserts by quoting Renée Cox, are “multiple and indefinite, cyclic, without set beginnings and endings.”38Renée Cox, “Recovering Jouissance: An Introduction to Feminist Musical Aesthetics,” in Women and Music: A History, ed. Karin Anna Pendle (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991): 331–40.

Macarthur uses beat-counting analysis to measure climax more accurately than counting measures, because the latter does not account for tempo changes.39Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 75 In the case of “Ansturm.” Macarthur measured the climactic proportions of the song settings, both of which she analyzed as ABA’ form, with Mahler’s at 3:1:1 and Zemlinsky’s at 5:1:10. Macarthur cites other examples of compositions by women with “top-heavy” ratios—by which she means ones in which the climax comes earlier than the divine ratio40Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 75 —including Moya Henderson’s Sacred Site for Grand Organ and Tape (5:1:1:2) and Marcia Citron’s analysis of the first movement of Chaminade’s Piano Sonata (5:1:2). A more comprehensive analysis of climax in the songs of Alma Mahler demonstrates that musical climax serves to express the text and realize her vision for a piece.

Climax in Mahler’s Lieder

The oeuvre of Mahler Lieder that were published during her lifetime is limited to fourteen songs, which makes it possible to consider them all.41Three of her songs have been published posthumously: “Leise weht ein erstes Blühn” (Hildegard, 2000); “Kennst du meine Nächte?” (Hildegard, 2000); and “Einsamer Gang” (The Wagner Journal, 2018).

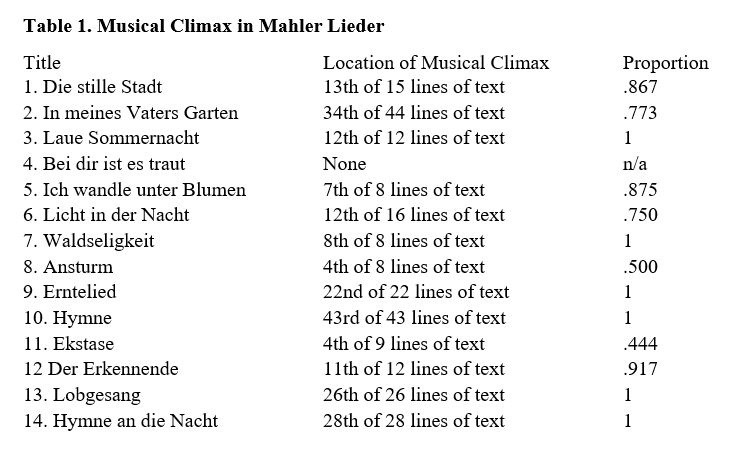

The first five songs under consideration were published as Fünf Lieder in 1910, the next four songs were published as Vier Lieder in 1915, and the final five songs were published as Fünf Gesänge in 1924. Table 1 shows where musical climaxes occur in these songs.

In Mahler’s Lieder, the musical climaxes overwhelmingly align with the textual climaxes. When a text lacks a climax, or is more understated, Mahler’s music follows suit. “Bei dir ist es traut” is her only song with no clear musical climax; the text by Rainer Maria Rilke evokes a quiet and potentially post-coital peace. Texts with relatively subdued textual climaxes are supported by appropriately subtle musical climaxes. For example, Richard Dehmel’s “Die stille Stadt” climaxes on the phrase “Aus dem Rauch und Nebel begann ein Lobgesang” [out of the smoke and fog began a song of praise]. This climax has more to do with clarity than exuberance, following up on the textual cue of a light shining in the phrase preceding the climax, “Da ging ein Lichtlein auf im Grund” [then a little light shone up from the ground].

Mahler Lieder with multiple musical climaxes set texts that feature multiple climaxes. For example, in Dehmel’s “Ansturm,” the piece analyzed by Macarthur, the first and strongest climax is set as the protagonist proclaims that the desire, if it is not to consume the pair, must come out into the light: “[Muß es heraus] ans Licht!” The weaker musical climax in Mahler’s setting deals with what some might consider the more explicitly orgasmic text: “und wenn herauf der Aufruhr bricht, jäh über deinen Frieden strandet, dann bebst du” [and when the tumult breaks out, abruptly washes over your peace, you quiver].

Climax in Zemlinsky Lieder

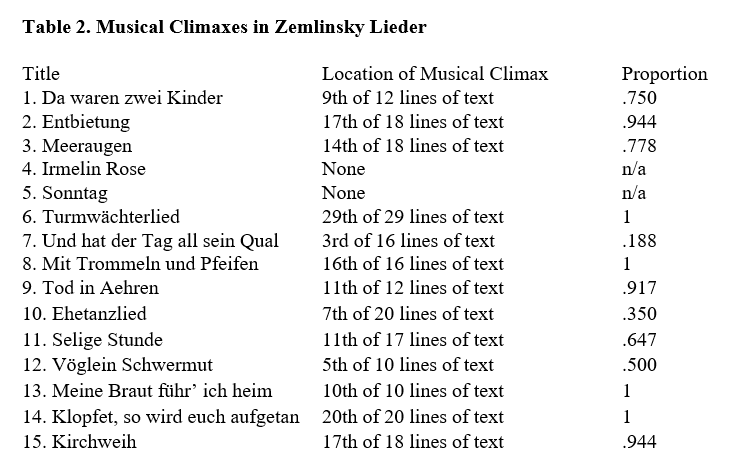

Zemlinsky’s earliest extant Lieder were composed in 1889, but for the sake of comparison, the songs evaluated in this study were published between 1898 and 1901.42Antony Beaumont, “Zemlinsky [Zemlinszky], Alexander,” Grove Music Online, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.30919. The first five songs under consideration were published as 5 Gesänge, opus 7 in 1901,43Zemlinsky dedicated these songs to Mahler, and she claims that “Irmelin Rose” was “her song”: Mahler-Werfel, Diaries 1898–1902, 381. the next four songs were published as opus 8 in 1901, and the final six songs were published as opus 10 around 1901. Table 2 lists where musical climaxes occur in the selected songs by Zemlinsky.

________________________________________________________________________

As in Mahler’s Lieder, a few of Zemlinsky’s settings feature early climaxes, but more songs feature climaxes that fall after the divine ratio of 0.618. Calculating the distance between the divine ratio and the climaxes reveals a greater distance from the divine ratio to the average early climaxes in Zemlinsky’s Lieder (.346) than Mahler’s (.472), and a greater distance from the divine ratio to the average late climaxes in Mahler’s Lieder (.926) than Zemlinsky’s (.898). That is, his early climaxes are further from the divine ratio than his late climaxes, and he more prominently subverts expectation with “top-heavy” climaxes than Mahler.

Late Romantic Tonal Practice, Formal Diversity, and Feminism

Alma Mahler’s musical settings of climax are varied. Just as they do not necessarily fall at the divine ratio, they also do not follow narrow guidelines as to their frequency, duration, or harmonic resolution. Climax, whether single, multiple, early, or late, is not subversive in the Lieder of Alma Mahler. Instead, the diversity of approaches to climax may be better understood as related to the lack of predictable or prescribed musical structure and regular phrases in late Romantic Lieder—regardless of the composer’s gender.

Early Romantic Lieder are frequently more homogenous than those composed in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; formally, they were more likely to have a strophic, ternary, or other standardized form that facilitated repetition of musical material. Relatively stable and regular phrase length also contributed to the stability and predictability of earlier Lieder. Harmonically, earlier Lieder were more likely to begin and end in the same, identifiable key, even if there were multiple modulations.44The songs of Franz Schubert present an exception in their frequent irreconcilability to diatonic tonality. See Richard L. Cohn, “As Wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert,” 19th-Century Music 22, no. 3 (1999): 213–32, https://doi.org/10.2307/746799.

Later works grew less diatonic as composers added chromaticism, made use of multiple tonic areas, and modulated to distant keys, which destabilized the pull of a single tonic center. Piano accompaniments also grew more varied and virtuosic, occasionally outshining the vocalist. Such changes provided turn-of-the-century composers with enhanced opportunities for expression. Both Mahler and Zemlinsky incorporated elements of prior practice while also innovating harmonically, formally, and stylistically.45 Poetic texts that were written in the late nineteenth century and were popular among Viennese composers including Mahler and Zemlinsky were likewise more diverse in form and style.

It is worth noting that all of Mahler’s published Lieder feature texts written by men. Accordingly, one might argue that in this respect, a gendered, and perhaps even masculine, perspective is inherent in and foundational to these songs.46Macarthur acknowledges the masculine authorial perspective in “Ansturm,” but explains that Dehmel “was in touch with his feminine side.” Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 77. Mahler’s composition teachers were exclusively men and she expressed contempt for women composers and their gendered limitations—Cécile Chaminade, for example.47Mahler points to Cécile Chaminade for evidence that women are incapable of creative work. After attending a performance of Chaminade’s Piano Concerto, opus 40, Mahler wrote in her diary: “Sie [Chaminade] ist eine Schande des weiblichen Geschlects … Nun weiss ich, ein Weib kann nichts erreichen, nie, nie, nie.” (She is a disgrace to her sex … Now I know that a woman can never achieve something, never, never, never.) Alma Mahler-Werfel, Tagebuch-Suiten 1898–1902, ed. Antony Beaumont and Susanne Rode-Breymann (Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 1997), 195. Mahler read broadly, and her diaries indicate that she read and grappled with the ideas of male authors. Mahler was not a feminist, neither by the standards of our time nor her own, and to assert that her music actively or intentionally subverts masculine and tonal traditions overlooks the extent to which she wanted her music to fit gendered genre norms, not to mention her explicit contempt for female composers.

That her musical climaxes do not align with the divine ratio does not suggest that Mahler was actively subverting it, but rather that she was more interested in expressing texts with appropriately sensitive and diverse musical settings. That Zemlinsky’s climaxes also do not align with the divine ratio suggests that it is not a helpful analytical tool for Lieder of this period. Although other elements of Mahler’s composition may indeed be understood as gendered, perceived differences in her composition of musical climax are based not in her sexual experience, but are instead a product of her commitment to expressing the poetic text and composing in a late-tonal style. Rather than an intention to subvert masculine traditions, the interaction of centripetal and centrifugal forces is at work in Mahler’s Lieder. Mahler’s composition of musical climax existed within the constraints of a masculine tradition; nevertheless, her timing and use of climax was part of her personal vision for each song.

Conclusion

Alma Mahler’s composition of musical climax can be understood as a product of her deep commitment to expressing the poetic text; she was frequently inspired by literary works and endeavored to compose music worthy of the text. Mahler’s gift for melody and her commitment to inhabiting a text and drawing all inspiration from it have garnered her admirers and performers. Women musicologists and theorists have championed her works and provided interesting ways to reconsider how these align with formal and harmonic conventions.

In the past few decades, feminist scholarship has contributed significantly to recent and mainstream considerations of Alma Mahler’s compositional work. Although such interest is welcome, it is nonetheless important to scrutinize claims made about the composer’s intent and to question analytical frameworks that are prescriptive or ascribe value only to compositions and composers who work within their narrowly defined systems. Recent scholarship suggests that making claims related to sexual experience is especially dangerous in the case of women whose legacies have been sexualized to the exclusion of their musical and other accomplishments.48 Nancy Newman, “#AlmaToo: The Art of Being Believed,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 75, no. 1 (2022): 39–79. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2022.75.1.39; Rachel Elizabeth Scott, “Taking Her at Her Work: Reconsidering the Legacy of Alma Mahler,” PhD diss., The University of Memphis, 2021. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/fpml/136/. See also Diane W. Follet, “Redeeming Alma: The Songs of Alma Mahler,” College Music Symposium 44 (2004), 28–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374487. In Mahler’s case, sexualizing her Lieder using descriptions such as “top heavy” and “premature ejaculation” runs the risk of perpetuating her stereotype as a femme fatale rather than a serious composer.

Although compositional conventions were gendered male during her lifetime, there is no evidence that Mahler was interested in subverting gender norms either in or through her work. Early climaxes, which would have subverted masculine stereotypes—whether consciously or unconsciously—by disrupting climactic expectations based on the divine ratio, are not a regular feature of Mahler’s Lieder. Instead, Mahler composed songs within an established and admittedly masculine tradition and hoped for them to flourish within it. The centripetal forces of genre, canon, and tradition are evident in her Lieder, and centrifugal elements of that bring out Mahler’s uniqueness may be better understood as expressive, rather than subversive.

[1] Alma Mahler-Werfel, Diaries 1898–1902 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000), 372–3.

[2] Susan McClary, Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

[3] Claims based on essentialist notions of binary gender have admittedly not aged well, but it is nonetheless important to contend with ideas set forth in what have become classic texts, such as those by Susan McClary. See also Ellie Hisama, Gendering Musical Modernism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001) and Sally Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002).

[4] Austin T. Patty, “Pacing Scenarios: How Harmonic Rhythm and Melodic Pacing Influence our Experience of Musical Climax,” Music Theory Spectrum 31, no. 2 (2009): 325–67, at 366, https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2009.31.2.325.

[5] Ji Yeon Lee, “Climax Building in Verismo Opera: Archetype and Variants,” Music Theory Online 26, no. 2 (2020): [2.7], https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.2.8.; Kofi Agawu, Music as Discourse: Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[6] The range is indicated using the Scientific Pitch Notation system in which C4 refers to middle-C on the keyboard.

[7] Much of the scholarship on climax in Romantic music focuses on large-scale instrumental works and opera—genres from which nineteenth-century women were largely excluded and genres that are admittedly radically different than Lieder.

[8] Peter Franklin, “Mahler’s Overwhelming Climaxes: The Symphony as Mass Medium,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 15, no. 3 (2018): 391–404.

[9] McClary, Feminine Endings, 100.

[10] Hugh MacDonald, “Schubert’s Volcanic Temper,” The Musical Times 119, no. 1629 (1978): 949–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/960118.

[11] Matteo Sansone, “Verismo,” in Grove Music Online, last modified January 20, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.29210

[12] Laurence Dreyfus, Wagner and the Erotic Impulse (Harvard University Press, 2012), 104.

[13] V. Kofi Agawu, “Structural ‘Highpoints’ in Schumann’s Dichterliebe,” Music Analysis 3, no 2 (1984): 159, https://doi.org/10.2307/854315. Agawu establishes the need formulate the experience of highpoints into an analytical model, which he does in this study—coupled with Schenkerian analysis—and in a subsequent monograph. Agawu, Music as Discourse.

[14] Marcia J. Citron, Gender and the Musical Canon (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 124–7.

[15] Mikhail Bakhtin, Dialogic Imagination (Austin, University of Texas Press, 1981), 425: “These are respectively the centralizing and decentralizing (or decentering) forces in any language or culture. The rulers and the high poetic genres of any era exercise a centripetal—a homogenizing and hierarchicizing—influence; the centrifugal (decrowning, dispersing) forces of the clown, mimic and rogue create alternative ‘degraded’ genres down below.”

[16] Gendering music and musical form extends much further back and has a history of one-dimensional readings and strong reactions, as documented by Scott Burnham, “A. B. Marx and the Gendering of Sonata Form” in Sounding Values: Selected Essays (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2017), 55–78.

[17] L. Poundie Burstein, “Their Paths, Her Ways: Comparison of Text Settings by Clara Schumann and Other Composers,” Women & Music 6 (2002): 11–28, 24–25.

[18] Hisama, Gendering Musical Modernism.

[19] The term double-voiced discourse originated in the work of Bakhtin, Dialogic Imagination, 324: “It serves two speakers at the same time and expresses simultaneously two different intentions: the direct intention of the character who is speaking, and the refracted intention of the author. In such discourse there are two voices, two meanings, and two expressions.” Elaine Showalter was among the first to apply “double-voiced discourse” and argues that women’s work “always embodies the social, literary, and cultural heritages of both the muted and the dominant.” Elaine Showalter, “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness,” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 2 (1981): 201, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343159.

[20] McClary, Feminine Endings, 112.

[21] McClary, Feminine Endings, 124.

[22] Erik Christensen categorized compositional processes as rule-determined, goal-directed, or indeterminate and identified Reich’s Piano Phase (1966) as a model of rule-determined processes that are bound by parameters established by the composer. This is in contrast to goal-directed processes, which are not governed by adherence to rules but are rather an “audible realization of the composer’s vision of the form.” Erik Christensen, “Overt and Hidden Processes in 20th Century Music,” in Process Theories: Crossdisciplinary Studies in Dynamic Categories, ed. Johanna Seibt, 97–117 (Kluwer, 2003), 107. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1044-3_5. Reich describes the appeal thusly: “This process struck me as a way of going through a number of relationships between two identities without ever having any transitions. It was a seamless, continuous, uninterrupted musical process.” Reich, Writings About Music (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974), 50.

[23] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 178.

[24] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 96.

[25] Alma Maria Mahler-Werfel, Vier Lieder (Vienna: Universal, 1915). Susan Filler dates Mahler songs published in 1915 based on dates in the initial publication and on manuscripts in the collection of Henry Louis de la Grange. Susan M. Filler, Gustav and Alma Mahler: A Research and Information Guide (London: Taylor & Francis, 2012), 30.

[26] Alexander Zemlinsky, Lieder aus dem Nachlass: Gesang und Klavier, ed. Antony Beaumont (Munich: Ricordi, 1995), 15.

[27] Richard Dehmel, “Ansturm” in Erlösungen: Gedichte und Sprüche (Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler, 1898), 136.

[28] All translations provided by the author.

[29] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 69.

[30] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 70. In musical analysis, the use of golden ratios can be contentious, regardless of whether it is perceived as gendered, but I include it here because it is central to Macarthur’s argument. For a recent meta-analysis of studies on the golden section in music, see Michelle E. Phillips, “Rethinking the Role of the Golden Section in Music and Music Scholarship,” Creativity Research Journal 31, no. 4 (2019): 419–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2019.1651243.

[31] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 70. I agree with Macarthur that studies employing golden section have largely perpetuated “great masterworks from the canon” (70). While the divine ratio may be helpful for understanding climax in the sonata form, where the return to tonic is expected around two-thirds of the way through the movement, in the case of turn-of-the-century Lieder climax is too dependent on the interaction of a variety of musical, textual, and performative elements to comply with a rigid and idealized ratio.

[32] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 76: “The opening accompaniment figure in the piano part of the Zemlinsky setting is appropriated by Alma Schindler-Mahler for the voice part.”

[33] Zemlinsky’s setting is in D minor and ends in D major. If considered with respect to the “tragic to triumphant” archetype, Zemlinsky’s minor to major shift might suggest a change of state that is gendered male in its triumphant closure. Robert Hatten, “On Narrativity in Music: Expressive Genres and Levels of Discourse in Beethoven,” Indiana Theory Review 12 (1991): 75–98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24045351.

[34] Macarthur, “The Power of Sound, The Power of Sex,” 74. Macarthur’s argument linking harmonic closure to subversiveness has more potential than arguments surrounding climax. Mahler avoided closure in multiple songs; this pattern of flouting genre conventions and user expectation may be interpreted as intentional and yield a more fruitful discussion of subversion. I would want this argument reconciled with Mahler’s extensive use of nonfunctional harmony for the expectation of harmonic closure. Macarthur acknowledged that “the composer avoids establishing a key or key center for the song and uses nonfunctional harmony extensively, thus indicating a move in the direction of atonality” at 73.

[35] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 74.

[36] Susan McClary most famously discusses gendered aspects of music theory, including cadence and closure, in Feminine Endings.

[37] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 70; Elizabeth Sayrs, “Deconstructing McClary: Narrative, Feminine Sexuality, and Feminism in Susan McClary’s Feminine Endings,” College Music Symposium 33/34 (1993/1994): 41–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374248.

[38] Renée Cox, “Recovering Jouissance: An Introduction to Feminist Musical Aesthetics,” in Women and Music: A History, ed. Karin Anna Pendle (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991): 331–40.

[39] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 75.

[40] Macarthur, Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 75.

[41] Three of her songs have been published posthumously: “Leise weht ein erstes Blühn” (Hildegard, 2000); “Kennst du meine Nächte?” (Hildegard, 2000); and “Einsamer Gang” (The Wagner Journal, 2018).

[42] Antony Beaumont, “Zemlinsky [Zemlinszky], Alexander,” Grove Music Online, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.30919.

[43] Zemlinsky dedicated these songs to Mahler, and she claims that “Irmelin Rose” was “her song”: Mahler-Werfel, Diaries 1898–1902, 381.

[44] The songs of Franz Schubert present an exception in their frequent irreconcilability to diatonic tonality. See Richard L. Cohn, “As Wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert,” 19th-Century Music 22, no. 3 (1999): 213–32, https://doi.org/10.2307/746799.

[45] Poetic texts that were written in the late nineteenth century and were popular among Viennese composers including Mahler and Zemlinsky were likewise more diverse in form and style.

[46] Macarthur acknowledges the masculine authorial perspective in “Ansturm,” but explains that Dehmel “was in touch with his feminine side.” Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 77.

[47] Mahler points to Cécile Chaminade for evidence that women are incapable of creative work. After attending a performance of Chaminade’s Piano Concerto, opus 40, Mahler wrote in her diary: “Sie [Chaminade] ist eine Schande des weiblichen Geschlects … Nun weiss ich, ein Weib kann nichts erreichen, nie, nie, nie.” (She is a disgrace to her sex … Now I know that a woman can never achieve something, never, never, never.) Alma Mahler-Werfel, Tagebuch-Suiten 1898–1902, ed. Antony Beaumont and Susanne Rode-Breymann (Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 1997), 195.

[48] Nancy Newman, “#AlmaToo: The Art of Being Believed,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 75, no. 1 (2022): 39–79. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2022.75.1.39; Rachel Elizabeth Scott, “Taking Her at Her Work: Reconsidering the Legacy of Alma Mahler,” PhD diss., The University of Memphis, 2021. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/fpml/136/. See also Diane W. Follet, “Redeeming Alma: The Songs of Alma Mahler,” College Music Symposium 44 (2004), 28–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374487.

Works Cited

Agawu, V. Kofi. Music as Discourse: Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Agawu, V. Kofi. “Structural ‘Highpoints’ in Schumann’s Dichterliebe.” Music Analysis 3, no 2 (1984): 159–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/854315.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Dialogic Imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

Beaumont, Antony. “Zemlinsky [Zemlinszky], Alexander.” Grove Music Online, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.30919.

Burnham, Scott. Sounding Values: Selected Essays. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2017.

Burstein, L. Poundie. “Their Paths, Her Ways: Comparison of Text Settings by Clara Schumann and Other Composers.” Women & Music 6 (2002): 11–26.

Christensen, Erik. “Overt and Hidden Processes in 20th Century Music.” In Process Theories: Crossdisciplinary Studies in Dynamic Categories, edited by Johanna Seibt, 97–117 (Kluwer, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1044-3_5.

Citron, Marcia J. Gender and the Musical Canon. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Cohn, Richard L. “As Wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert.” 19th-Century Music 22, no. 3 (1999): 213–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/746799.

Cox, Renée. “Recovering Jouissance: An Introduction to Feminist Musical Aesthetics.” in Women and Music: A History, edited by Karin Anna Pendle, 331–40. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Dehmel, Richard. Erlösungen: Gedichte und Sprüche. Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler, 1898.

Dreyfus, Laurence Wagner and the Erotic Impulse. Harvard University Press, 2012.

Filler, Susan M. Gustav and Alma Mahler: A Research and Information Guide. London: Taylor & Francis, 2012.

Follet, Diane W. “Redeeming Alma: The Songs of Alma Mahler.” College Music Symposium 44 (2004), 28–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374487.

Franklin, Peter “Mahler’s Overwhelming Climaxes: The Symphony as Mass Medium,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 15, no. 3 (2018): 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479409818000332

Hatten, Robert. “On Narrativity in Music: Expressive Genres and Levels of Discourse in Beethoven.” Indiana Theory Review 12 (1991): 75–98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24045351.

Hisama, Ellie. Gendering Musical Modernism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Lee, Ji Yeon. “Climax Building in Verismo Opera: Archetype and Variants,” Music Theory Online 26, no. 2 (2020): [2.7]. https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.2.8.

Macarthur, Sally. Feminist Aesthetics in Music. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

MacDonald, Hugh. “Schubert’s Volcanic Temper.” The Musical Times 119, no. 1629 (1978): 949–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/960118.

Mahler-Werfel, Alma. Diaries 1898–1902. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Mahler-Werfel, Alma. Tagebuch-Suiten 1898–1902, edited by Antony Beaumont and Susanne Rode-Breymann (Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 1997).

Mahler-Werfel, Alma Maria. Vier Lieder. Vienna: Universal, 1915.

McClary, Susan. Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Newman, Nancy. “#AlmaToo: The Art of Being Believed.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 75, no. 1 (2022): 39–79. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2022.75.1.39.

Patty, Austin T. “Pacing Scenarios: How Harmonic Rhythm and Melodic Pacing Influence our Experience of Musical Climax.” Music Theory Spectrum 31, no. 2 (2009): 325–67. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2009.31.2.325.

Phillips, Michelle E. “Rethinking the Role of the Golden Section in Music and Music Scholarship.” Creativity Research Journal 31, no. 4 (2019): 419–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2019.1651243

Reich, Steve. Writings About Music. Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974.

Sansone, Matteo. “Verismo.” In Grove Music Online. Last modified January 20, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.29210

Sayrs, Elizabeth. “Deconstructing McClary: Narrative, Feminine Sexuality, and Feminism in Susan McClary’s Feminine Endings.” College Music Symposium 33/34 (1993/1994): 41–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374248.

Scott, Rachel Elizabeth. “Taking Her at Her Work: Reconsidering the Legacy of Alma Mahler.” Ph.D. diss., The University of Memphis, 2021. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/fpml/136/.

Showalter, Elaine. “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness.” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 2 (1981): 179–205. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343159.

Zemlinsky, Alexander. Lieder aus dem Nachlass: Gesang und Klavier, edited by Antony Beaumont. Munich: Ricordi, 1995.