Venturing across disciplines in musical practice and pedagogy is often seen as a path fraught with peril, yet the scholarly, artistic, and even financial benefits far outweigh the risks. Thor Steingraber, Vice-President for Programming at The Music Center (Los Angeles), observed, “when interdisciplinary projects succeed, they can generate positive PR, engage new audiences, and advance the art form.”2This article not only highlights these benefits with examples taken “from the field,” it also intends to place the often misunderstood act of musical crossover within the wider framework of creative development while providing logistical advice for musicians and scholars who wish to venture beyond their specialty. We will explore the nuances of detail-oriented music genre crossover as well as collaborative creativity between different fields of study.

Research for this article is based partly on Louis Diez’s experience running Music Arts Management, an agency that endeavors to create opportunities for future generations of musicians by connecting artists of the highest artistic caliber with professors in higher education and their students.3 We also interviewed some of our clients and prospective clients: music programmers from performing arts centers across the nation. Finally, we chose trumpet player Marvin Stamm as a case study in the practice of making music across disciplines while remaining dedicated to the most elevated musical values. The information gathered on the art and practice of crossing boundaries is synthesized in three main areas: first, we explore the issue of artistic integrity and its relationship with cross-disciplinary creation; second, we examine current trends in the study of creativity and its academic and educational benefits, anchoring the concept of crossover within this wider vision; and finally, we provide organizational and funding ideas derived from interviews with presenters across the United States.

Crossing Over: An Artist’s Perspective

To illustrate the creative potential and artistic challenges of cross-disciplinary creation as they apply to the realm of music performance, we were pleased to interview Marvin Stamm, a Memphis-born Jazz trumpeter who has recently embarked on several projects that combine classical and jazz idioms.4

Mr. Stamm received his B.M. with a major in trumpet at North Texas State University (currently University of North Texas). There he made the acquaintance of Stan Kenton who recruited him for the Mellophonium Orchestra. Later, he was engaged as trumpet soloist by leading ensembles (Woody Herman, 1965-1966; Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, 1966-1973; Duke Pearson, 1967-1972; Benny Goodman, 1974-1975). From the time of his arrival in New York City in late 1966 through 1990, he also established a career as a session and studio musician. In this period, he recorded with Bill Evans, Average White Band, Quincy Jones, Donald Fagen, Oliver Nelson, Patrick Williams, Wes Montgomery, and Freddie Hubbard among others.

Audio Example 1: The flugelhorn lick on Paul McCartney’s hit song “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” that, for a time, made Marvin Stamm “The Most Famous Unknown Trumpeter.”

In the 1990s, Mr. Stamm decided to return to his origins as a jazz musician, performing with a variety of ensembles and dedicating a part of his efforts to mentor the next generation of jazz artists. Mr. Stamm has generously agreed to answer some of our questions concerning crossing over and creative collaboration.

LD: What does “crossing over” mean to you?

MS: To a performer who, like myself, enjoys playing many kinds of music, “crossing over” might mean the melding of a broad panorama of musical styles with which to express oneself. To the purist, however, “crossing over” sometimes means the sullying or “dumbing down” of the art form. Yet we are finding artists such as Yo Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Bobby McFerrin, and others who also enjoy performing music that incorporates different styles and receiving accolades in the highest echelons of the classical field for crossing over into music outside of their usual performance areas. Among these are country music, bluegrass, jazz, and other various ethnic musics. Would these artists be accused of “sullying” the art form? And what of the jazz world? Is a classically-trained jazz performer, playing music that incorporates both jazz and classical styles, considered to be “dumbing down” the music?

As a professional musician, I would define “crossing over” as the exploration of alternative avenues aimed toward enriching our sensibilities, a willing acceptance of challenges that carry the potential for expanding and enhancing our performance vocabulary. Several instances taken from my own personal experience should help to clarify my viewpoint.

There have always been those who see this subject from a purist’s perspective. This seems to be especially true emanating from the classical side of academia, although I do not find this to be true of most classical performers—those who increasingly accept and enjoy a rather broad range of musical styles.

Some jazz artists, too, may feel that mixing the music is a dilution of the art, though probably less so than the classical purists. This may be because most jazz musicians are unable to make a living playing only jazz. They must also perform in other more lucrative areas in order to make ends meet—shows, free-lance concerts, social functions, weddings and many more. The jazz musician learns this pretty much at the beginning of his career. It’s a choice between purity and survival. I imagine this subject could be argued endlessly, however, and I highly doubt it will be resolved here. So what does this mean to someone like me? Actually, it means a great deal.

My musical journey has been much more than merely that of a jazz musician. When I started playing in Memphis, the public school system offered only traditional band programs. These bands played everything throughout the year—parades, football games, concerts, etc. We had no separate marching band or pep band, and certainly no jazz ensembles in those days. The band WAS the band, the only band, and our one group played everything.

My jazz training came at first from my older brother’s collection of jazz recordings, but with my teachers’ guidance, I was also buying and listening to orchestral recordings. I was performing concert band music while continually working to master my instrument through daily practice. At the same time I was also being encouraged by my directors to listen to all kinds of music—for enjoyment as much as education. Having been musically coached in this manner, I came to love many kinds of music—band music, orchestral music, jazz, and—living in Memphis—the blues.

Through attending college and going out into the world as a working musician, my appreciation of other music grew as my world expanded. Living and working with older musicians, those who had more life and musical experience than I, opened up new worlds to me. My stylistic repertoire grew as did my tastes for a number of different idioms of music. It follows that this would all be incorporated into my performing, thereby contributing greatly to my versatility, my creativity, and my good fortune to become one of the busy studio artists of the late 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. During this time, I also continued to develop my own voice as a jazz performer while playing with numerous artists from many areas of music, giving me a wide palate from which to create my own music.

Photograph of Stan Kenton, Marvin Stamm, Gabe Baltazar, Dee Barton, and Jim Amlotte]. UNT Digital Library5

Photograph of Marvin Stamm (second from left), Gabe Baltazar (fourth from left), Dee Barton (fifth from left), Stan Kenton (fourth from right), and Jim Amlotte (third from right) with members of Count Basie's band.

Photograph of Marvin Stamm (second from left), Gabe Baltazar (fourth from left), Dee Barton (fifth from left), Stan Kenton (fourth from right), and Jim Amlotte (third from right) with members of Count Basie's band.

LD: What is your philosophy when approaching the performance of works that combine jazz and classical idioms?

MS: My approach to crossing over between both the jazz and classical idioms is really quite simple. Since I have grown up with a love of both idioms and have steeped myself in both for many years, I quite naturally use elements in style and interpretation from both. Though I am a jazz artist, I have been greatly influenced by my classical studies—which, perhaps surprisingly, make up most all of my daily practice materials. The influences from years of playing and listening to both classical music and jazz, as well as the respect coming from my relationships with musicians from the two sides of the music, are a natural part of my music. I believe the most telling aspect of my music would be my sound—especially when playing lyrical passages in ballads. That’s because I have listened so carefully over the years. And because I have consistently performed a wide array of music throughout my career, playing what might be considered crossover music seems only natural to me. In my mind, music is music. The player must understand what the composer wants his composition to express, and then work towards bringing this out in the performance—the task being the melding of two individual spirits, that of the creator and that of the interpreter. The music itself will dictate direction and style, and the performer will interpret it.

Preparation for any performance demands a serious and respectful attitude, and one should not become involved if both “serious” and “respectful” cannot be felt. My preparation for performing all different styles of music is done with the same serious attitude as for any of my pure jazz performances. Actually, my preparation for both jazz and classical performances is quite similar. I consistently practice the “fundamentals” required to maintain a high level of mastery of my instrument. Among these are technique, flexibility, and sound, as well as other musical and technical aspects required to bring a performance to fruition. The difference between the two areas of music is that the performance of classical or “crossover” pieces requires attention to written parts whereas jazz performance involves improvisation—or instantaneous composition. I use the same technical and musical skills for any style of music I play, and while playing classical music requires my attention to be focused on bringing the written notes to life, performing as a jazz artist requires something entirely different.

Jazz artists typically realize early on that improvising—or composing “in the moment,” with one’s instrument—is a linguistic skill, and one speaks musically with his instrument similar to using his voice when expressing himself verbally. This ability to “speak” is developed over many years of experiencing this music and developing one’s own voice.

When I play a tune such as “How Deep Is The Ocean,” I am not focusing on my technique or flexibility, or even my sound. These things, by now, should be implicit. Rather, my attention is focused on being able to compose melodic lines based on the musical elements in which I find myself immersed and the musical contributions of the cohorts with whom I am playing. While focused on my own lines, I am also focused on the chord changes and voicings the pianist is utilizing, the lines played by the bassist, and the rhythmic elements of the drummer. Though I am the soloist at that moment, all of the various elements my musical companions contribute influence the lines I am playing, the sounds I am producing, and whatever techniques I may be employing. But those techniques are not the focus of my attention. The lines I am playing are what bring into play whatever elements of technique I use.

Video Example 1. Clip of “How Deep is the Ocean”

Every composition presents its own challenges. Preparing any piece requires one to recognize these challenges and find his own approach to meeting them. My approach is to first try to work out the technical aspects of a piece so that I am unencumbered by the notes and therefore free to plumb the musical depths it offers. While working on these pieces I try to find suitable parallel material that can aid in my interpretation of the performance piece. The materials I typically draw upon are etude methods such as those by Charlier, Bozza, Bitsch, and others. These and similar studies present numerous technical tasks, but pose a variety of musical challenges as well. And because they are unaccompanied etudes, there is no other musical influence to rely upon, so the player is left to his own devices regarding interpretation.

With these etudes, I find myself consistently working on technical fluency in all keys. I also am confronted with atonal pieces exhibiting unusual harmonic passages or being challenged by studies with long melodic passages meant to train the player in musical interpretation while also emphasizing breath control. These various studies are classic texts containing all the elements one would probably come across in any piece. I find working with them in conjunction with the particular piece I might be performing reinforces most all the elements I need for my performance.

I love to play music regardless of the idiom from which it is drawn, and as stated above, each performance is taken seriously. Maintaining my fundamental practice, while including other musical texts to aid in developing the pieces to be performed, helps everything come together at the time of performance.

Regarding interpretation, whatever the music presents from the jazz perspective demands that I draw upon my many years performing in this idiom. I have progressed in my listening and playing from the early eras of jazz (Louis Armstrong, etc.) through the Swing Era, BeBop and even into some avante garde. If I don’t feel comfortable about my interpretation, I discuss the composition with the composer to understand his or her thoughts on the matter and move forward from there. Many times I will suggest practicing the piece together so I can more clearly understand what the composer wants.

LD: You premiered a work by Greg McLean that has two trumpet soloists, one representing the classical and the other representing jazz traditions. What challenges did you encounter in practice and performance?

MS: When composer Greg McLean approached me about his writing a new composition for me, we decided the piece should feature two trumpet soloists, one a classical soloist and the other a jazz soloist. The basic palette would be symphony orchestra [and] also utilize a jazz trio. From this initial concept, the concerto “The Twain Have Met” came to fruition.6

The challenges for me were three-fold. The written parts played with my counterpart had to be played in the classical style and the blend between the soloists that of two classical players; the improvisations were to be deeply authentic; the written “solo” passages were to be lyrically expressive as demanded by the various styles. As the piece developed, Mr. McLean made a synthesizer mock-up of the ensemble so I would be able to hear the direction he heard the music moving. His effort helped me a great deal in working out the parts and hearing the counterpoint between the two solo parts, but it was certainly not like working with an orchestra. That would be several years away.

The real fun always comes in the rehearsing and performing, where one has the opportunity not only to explore the notes on the page, but also to experiment with various ways to bring out the most in the music. My first performance of Mr. McLean’s work, playing with Cathy Leach (principal trumpet, Knoxville Symphony Orchestra) and the University of Tennessee Orchestra, gave me the opportunity to explore the piece in depth. Ms. Leach has a beautiful sound, and blending with her sound and interpretation on the classical parts was an easy task. Playing the written lyrical parts also came together easily because of the beautiful melodic passages Mr. McLean had written. The real challenge might have been the improvised sections—except for the marvelous trio comprised of pianist Bill Mays, bassist Rusty Holloway, and drummer Keith Brown. The importance of having a fine trio with which to play cannot be emphasized too strongly. Any challenges were easily met by having had great colleagues and a fine orchestra with which to perform.

As previously shown in the video of the Marvin Stamm Quartet playing “How Deep is the Ocean,” Stamm's emotive interpretation of the ballad genre demonstrates a clear aptitude for fitting within the style at hand. His apt choice of notes, bluesy tone, and rhythmic fluency (fluidity too!) all contribute to a confident expression that leaves Stamm free to listen to the other musicians in the group. Here the listener finds a combo comfortable enough in the music to sit back and dialogue in a healthy exchange between instruments. The result is a musical playground for the careful listener. Stamm's communicative abilities, as he already mentioned, are not merely limited to listening exclusively to jazz musicians.

In "The Twain Have Met," soloists Stamm and Cathy Leach share the spotlight to participate in Greg McLean's compositional evolution "The Twain Have Met" as the melody morphs from a classical orchestration to an intimate jazz combo setting. The resultant product employs crossover sounds between styles to create a subtle shift in expression while maintaining the essence of McLean's remarkable melody.

Audio Example 27

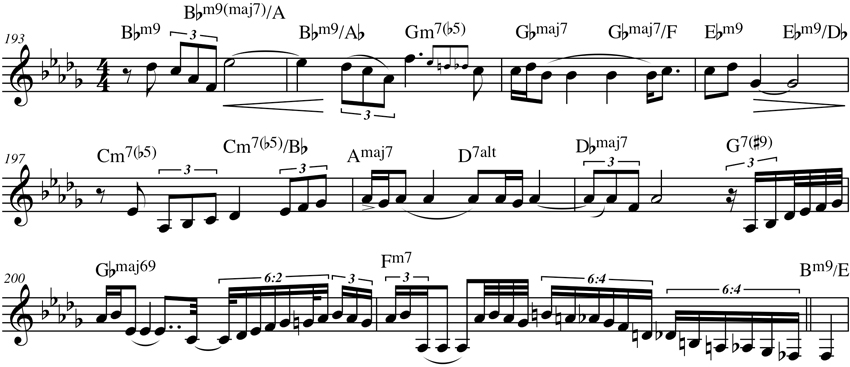

Leach does an admirable job of rolling with the punches as the elements of counter-melody and counter-rhythms shift between orchestral voices underneath her own melody; one senses a setting of the table for what is yet to come by way of her pared down statements. In this performance, Leach's tone is brassy yet never shrill, confident and at the same time vulnerable to the harmonic shifts that McLean imposes, with few apologies, on the melody. The composer waits only three measures before modulating from his opening B-flat minor tonality to A major (mm. 179-80), a mere minor second away from the tonic. McLean goes further by dividing the phrasing into sub-groups of five (mm. 176-80), six (mm. 181-86), four (mm. 187-90), and two (mm. 191-192) for an unconventionally prime-numbered measure grouping. One of the most engaging elements of McLean's writing lies in this ability to say the same triplet figure over and over again (mm. 181-185) without losing the attention of the listener. In applying such simple melodic hooks (mm. 184-185), McLean finds room to modulate one more time from the tonic B-flat minor into D major as he arrives at the third grouping (mm. 187-90), yet another distantly related tonal center. Through it all, Leach plays on, seemingly impervious to the musical storm McLean creates around her. By the time the listener, deprived of stability, arrives at Stamm's solo (m. 193, shown below), they are set up for a crossover into a winsome new dimension.

The intimacy of Stamm's playing cuts to the heart of the melody, and finally, McLean leaves the soloist free to express the melody without extraordinary shifts in tonality, meter, and sound. This time there remains simply a skeleton framework of chord progressions for the small combo. By taking a few risks, Stamm shows his proficiency for cross-relating the music into a jazz setting—and it all starts with his sound. Sexy and sumptuous, Stamm crescendos through his phrases and emphatically declaims some of the more appealing notes in the harmony, undeniably persistent in the evolving Ab of mm. 198-99 that serves as the seventh, thirteenth, and fifth of the respective chords. In doing so, Stamm tips his hat to Leach's interpretation of the melody while leaving enough contrast for him to arrive as a jazz man in his own right. As shown in the musical examples, similar figures are played by both soloists (see mm. 176-79, 193-96), and yet Stamm's musical identity elicits a reflective response in the jazz quartet that seems to clasp onto the ponderous void left by the orchestra. His playing bounds from one phrase to the next so effortlessly that the listener forgets they are listening this time to two nine-measure asymmetrical phrasings, yet another contrivance in the style of McLean. It seems the composer wanted the twain to meet after all! At the end, Stamm simply seems to float away with a descending Bb lydian harmonic minor scale, softly landing on the major 7th at his arrival on the downbeat Bill Mays's piano transition.

Audio Example 38

Audio Example 4: “The Twain Have Met” in its entirety.

LD: You also co-founded the Inventions Trio. How did you get the idea of putting together a trumpet, a cello, and a piano to explore the jazz-classical crossover?

MS: One of the truly fulfilling groups I currently work with is the Inventions Trio, in which pianist Bill Mays and cellist Alisa Horn join me in an ensemble “crossing over” to produce music that includes a rather uncommon mixture of sonorities.

Video 2: Example of Webernian integral serialism in the second movement of Bill Mays’ Delaware River Suite (2008)

Bill Mays and I have been working together in various combinations since 1995. In 2004 we were invited to perform at the University of Memphis for that school’s Jazz Week. While in Memphis we were invited to brunch at the home of Dr. and Mrs. Howard Horn, friends of mine for many years. Their daughter Alisa, a very talented cellist, was home from school at the time, and I hoped Alisa would play for Bill. It had been in my mind for several years to propose that Bill compose something for us—an extended piece for cello, piano, and flugelhorn. I couldn’t suggest such a project, however, without Bill’s having an opportunity to hear Alisa play. I believed that upon hearing her he would be excited by her musicianship.

Alisa played an unaccompanied Bach cello suite, then Ernest Bloch’s “Schelomo,” accompanied by her mother. Bill asked to play with her, and they went through the Rachmaninoff cello sonata. Bill, a classically-trained jazz pianist, was sight-reading the very difficult piano part! Bill is fearless—suffering absolutely no trepidation, never afraid to try anything—because music is always such great fun for him. As they went through the Rachmaninoff, everyone could feel their [music] coming together. It was a beautiful moment.

Bill and Alisa were immediately captivated with each other, so on the flight back to New York, I proposed that Bill compose a piece for the three of us. Bill was taken with the idea, adding that if he could somehow acquire a commission to put aside the time to compose an extended trio, he would love to do so. Over time, Alisa’s father and good friend Dr. Frank Osborne granted the commission, and Bill set to work.

Video 3: Except Boogie from Delaware River Suite 24:37 – 28:37; Artistic take on boogie-woogie from Bill May’s Delaware River Suite (2008)

“Fantasy for Cello, Trumpet, and Piano,” a three movement, through-composed piece came to life and gave birth to the Inventions Trio. As previously stated, Bill and I are classically-trained jazz musicians, while Alisa Horn is a classical cellist, a student of Peter Spurbeck, Anthony Elliott, and Hans Jorgenjensen. She now resides in New York, where she performs in concert and recital with various groups as well as doing studio recordings and Broadway shows.

“Fantasy” is written almost wholly in the classical style, but has sections of improvisation from all three instrumentalists throughout its three movements. It is truly a wonderful work, beautifully musical and expressive, giving each of the instruments its due and each instrumentalist an opportunity to shine.

While Bill and I were steeped in both the classics and jazz, Alisa was strictly a classical cellist. The greatest challenge for us, beyond our rehearsing and mastering the piece from a note and interpretation perspective, was Alisa’s “crossing over” into improvisation and learning to “walk bass lines”—that is, perform the functions in certain sections of the music as a bassist in a rhythm section.

Alisa from a very early age learned to play “by ear” as a Suzuki student. She picked up everything very quickly, her only problem being the need to overcome her fear of making a mistake, a malady common to many classical musicians. Most classical musicians strive to play “note perfect” while jazz musicians try for instantaneous creativity—creating music “of the moment.” While perfection may be somewhere in the back of the mind, creativity of mood, lines, dynamics, and feeling are utmost in jazz musicians’ thoughts. Alisa crossed beyond her compulsion for perfection to become a fearless and most passionate musician absorbed in this new kind of music.

The excitement among the three of us was palpable, and Bill wrote new material which we recorded for our first CD, “Fantasy.” As we kept expanding our library, we rehearsed and looked forward to touring. We have now been together for seven years and have just released our third CD: “Life’s A Movie.”

Preparation for work with the Inventions Trio requires that I cross over to a different approach than when playing jazz. It is important that I don’t envision myself as a solo trumpet player, but rather as a part of a three-piece ensemble. Though there are a number of moments that the music asks me to play as a soloist, it also demands that I subjugate my sound and style to be part of an ensemble led by the cello—or play in duo with her wherein I must blend as a string instrument—or in combination with the piano to produce a single combined sound rather than our sounding as two individual instruments. This is a very enjoyable challenge for me. It requires my having complete control of my sound and dynamics while also being sensitive to and aware of what the other players are doing at all times.

One must develop these musical skills, but first one must be able to “hear” them. Let me explain. I hear many players who just “play.” They seem not to truly listen to or hear what they sound like in most of the settings in which they play. They just blow the horn. This would never work in a group such as ours. Even Alisa has to alter her sound for the various combinations called for in Bill’s compositions. This is the challenge, but also the fun of playing with this group. It requires one to use his or her musical skills to the utmost. It is not about “chops” and technique, but rather a musical melding and blending to make the music. One must think beyond self, “giving it up” for the group. While there is plenty of room for individual creativity and spotlight, the essence of the composed music is about the group. This is essential to the success of any group such as the Inventions Trio.

LD: What are your upcoming projects in this exciting area?

MS: Throughout my career I have performed all kinds of music, especially during my studio years. But my strongest influences were always from the jazz and classical idioms, the greatest thrust being toward the jazz area. In 1990 I left the studios to pursue a career as a jazz artist, but due to my reputation as a versatile player, there were still composers and arrangers who wanted to write for me, incorporating both idioms. I have a great love for classical music, so it seems only natural for me to involve myself whenever opportunities arise. And they still do. We have spotlighted Greg McLean’s trumpet concerto. Currently, Gerald Ascione, a dear friend and fine composer, is writing two pieces for concert band or wind ensemble that will feature me as soloist. I continue to enjoy the challenge of developing a piece and bringing it to its musically successful apex.

A final thought: I feel it rather silly trying to categorize music into tiny niches to determine whether it is pure, crossover, or whatever label one might place upon it. Music is very personal. And taste is individual. It is not in my place to judge one’s likes and dislikes—only whatever does or does not touch me. Having said this, I never agree to perform anything I don’t musically believe in or that is far beyond my abilities (as some things are). It is not a matter of “playing it safe,” but rather being true to myself while appreciating the opportunity to respect the writer and his music, and to extend one’s ultimate effort in bringing that music to life.

Academic and Educational Benefits of Cross-Disciplinary Projects

In our innovation-driven culture, thinking "outside the box" is an indispensable trait for success-bound students; after all, brazen creativity drives the arts as well as the economy. Organizations such as the Curb Center for Art, Enterprise and Public Policy, at Vanderbilt University, are recognizing the value of providing college students with an environment where they can build on creative thinking outside of their own disciplines. Their Scholars Program takes aim at educating a generation of thinkers ready to ask “provocative questions, manage ambiguity, take risks, experiment, and lead innovation for the public good.”9 Such nebulous concepts take shape in the form of group initiatives to come up with gross strategies for thinking wrong, that is, to find a big problem such as the lack of vaccination against measles in Somalia and Chad or the feeble state of arts development programs in the United States and spend ten minutes with sharpies and post-it notes brainstorming the most wrong-minded ways to solving the problems before sharing the ideas with the group. The more bizarre and more detailed the incorrect nature of the proposal, the more students can gravitate towards the inverse of these ostentatious ideas—carefully distilled solutions that make an impact on society.10 Curb Center moderators focus on integrating creative thinking habits that can span any curricula across the Vanderbilt campus by encouraging free improvisation in group settings, expressive agility to authentically share one’s identity and elicit reflective responses in others, epistemic curiosity that embraces problems with no pre-defined answers, and pattern recognition to identify important trends. Although such methods may initially cause discomfort among participants, the presence of a positive and supportive environment can set the stage for a provocative learning experience ultimately guiding students to confront real world problems in a meaningful way once they leave the confines of Vanderbilt.

There is a clamor for artistic relevance in this media-saturated world of Twitter and YouTube, and in the United States, individuals involved in the fine arts are in the heat of a battle yet to be won. Rather than attending customary venues such as concert halls and museums for social experiences, studies reveal that younger generations are increasingly searching for organic, community-based, intra-communicative, and improvisatory forms of audience participation.11 Today, arts programs are often stymied by old-world views that exclude multi-disciplinary work in favor of business models and group missions fostering exclusivity of genre and presentation style. Couple such variations with the differences found in languages and even clothing styles between artistic sub-cultures—the result leaves little room for united growth.12 This combination of old-world cooperation (rather than engaged collaboration) and rapidly evolving tastes of the 21st century public strikes at the heart of the disparity the Millenial generation is contending with today.

The Curb Center’s work on forming a globally creative Vanderbilt campus sparked a grant program from the Association of Performing Arts Presenters (APAP) funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. This organization aims to implement creative programs that integrate the performing arts with various academic communities at higher education establishments around the country. Such support came in the form of grants totaling $1 million at institutions such as Montclair State University, the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University, and the Center for the Arts at Wesleyan University, among others. Below, performing arts consultants Alan S. Brown and Steven J. Tepper outline five barriers standing in the path towards the arts gaining a role as cultural leader in society. It is the imperative of associations like the APAP to find sustainable solutions to the issues below that will germinate veritable cultural solutions for years to come.

- Financial imperatives often lead to the selection of artists and artistic works that are ill suited for deeper levels of engagement.

- The economics of touring can work against the needs of presenters to have artists spend enough time in communities to make deeper connections.

- The theaters and concert halls used by some presenters were not designed to promote social interaction or civic discourse.

- Some presenters are stuck in a decades-old programming formula that is difficult to break without sufficient risk capital or new creative energy.

- The processes by which artists are selected can be insular, especially when decision-making authority is overly centralized.13

In a world increasingly fluent in the blending of traditions and genres, organizations like the APAP stand as a harbinger to shifting societal trends and manners of creative expression.

Beethoven and the Romantic ideal of the “creative genius” strikes one first as one of the clearest examples of boundary-breaking creativity. There existed something special about this autodidactic composer who learned the old rules (often by emulation in his early period compositions, especially his Symphony No. 1) before learning to “think wrong.” His highly documented struggle with deafness characterizes the development of an individual willing to break formal precedents in search of personal expression. Today, in similar fashion, there is a growing perception that the best way to address human problems is by joining with elements of various disciplines.14 Certainly in the music world, the synthesis of contrasting styles has led to some of the great works of our time. Debussy’s Estampes (1903) or Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (1924) readily come to mind. Fortunately, there is a growing body of literature that indicates creativity can be taught. Forward thinking educators and administrators around the country are seeking to make synthesized creativity a permanent part of their curricula.15 As such, the Arts are a natural fit for any modern trend toward teaching creativity and developing inter- and cross-disciplinary collaboration. Such unions are already building momentum. In a 2013 article from The Chronicle of Higher Education Dan Berrett calls attention to these significant developments:

Starting this fall, Stanford University . . . will require incoming students to take a course in "creative expression" as part of its new general-education curriculum. Students at Carnegie Mellon University's Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences must satisfy a "creating" requirement, in which they produce a painting, poem, musical performance, piece of technology, or design an experiment or mathematical proof. And Bryant University requires students to take a first-year seminar in design thinking.

Adrian College, in Michigan, started an Institute for Creativity to weave the subject into the curriculum. The University of Kansas and the City University of New York recently adopted new general-education requirements that students in all disciplines take a course to develop their creative skills.16

In the twenty-first century, educators are beginning to realize that inter-disciplinary creativity is not merely a chic pastime but a veritable pathway to success.

There is a specific model of musical creation that epitomizes the benefits of creativity, and it is the intersection of contrasting musical styles commonly called “crossover.” A union of styles has great potential from a creative and educational perspective—for example, the skills necessary for successful jazz performance are directly linked to the creative mindset advocated by Curb Center educators: free improvisation in group settings, expressive agility to authentically share one’s identity and elicit reflective responses in others, and epistemic curiosity that embraces problems with no pre-defined answers. Classical music, on the other hand, involves focused efforts on homogeneous sound ideals, precise stylistic interpretations, and pattern recognition.

“Third Stream,” a term sometimes used to describe the intersection of the jazz and classical traditions in music, was coined by Gunther Schuller in 1957 for a lecture at Brandeis University in Boston.17 Duke Ellington, for example, began exploring extended classical forms with works like Black, Brown, and Beige and the Concerto for Cootie after a youthful formation following the stride music styles of James P. Johnson and Willie “The Lion” Smith. Although Third Stream music has existed for decades, its application into the world of creative thinking remains fertile soil. It is precisely within this arena where we will begin to cross the bridges of style for a new take on cross-disciplinary activity within art music.

Brief How-To Guide for Interdisciplinary Projects in Higher Education

Educational initiatives that span multiple academic subjects are enriching opportunities for all involved. Interest in nurturing creativity and deep learning is on the rise thanks in part to the previously mentioned Creative Campus grant program from the Association of Performing Arts Presenters. To discover what makes these projects successful, we surveyed cross-campus projects involving the arts from Montclair State University, the Music Center, the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University, Wesleyan University, and the University of Tennessee. They all showed potential to stimulate learning on a vast array of subjects.

Carrie Urbanic, Cultural Engagement Director at Montclair State University, worked with MSU's Research Academy for University Learning (RAUL) and an interdisciplinary group of faculty to create a semester-long course on creativity that incorporated visits to campus by artists through MSU's Peak Performances series. She notes that artists should be preselected for these types of projects. One must strive to choose those individuals who will be as comfortable as possible in what could be uncharted territory. Often, selecting someone with practical experience will help make the project a success.

Other benefits often cited for these projects are their social impact to engaging academic participants in cross-pollinating ways. Director of Performing Arts at the Wexner Center Chuck Helm believes that “cross-disciplinary learning projects allow different areas to contribute their own academic perspectives.” Thor Steingraber, Vice-President for Programming at The Music Center, adds, “it is crucial to engage people in new, nontraditional ways . . .”

For music educators, initiating a project of this kind is an opportunity to bring guest musicians to campus, locate funding outside the usual channels, and advance both their institutional effectiveness and academic careers.

In our conversations with presenters, several important questions came up regularly:

- How is your project going to engage students and faculty around campus? Guest artists can be incorporated into master courses or modules, workshops, and performances.

- Will this project receive support from senior faculty and administration? Barbara Ally, Associate Director for Programming and Events at Wesleyan University, shared her extensive experience with us and revealed that this is a crucial element for cross-disciplinary programs to succeed.

- What collaboration opportunities exist? Both inter-departmental (i.e., jazz and classical programs, music and dance areas) and intra-departmental (i.e., Business School and School of Music) options should be considered

- Do participating artists have an educational background? Do they have experience not just performing but also teaching and discussing their art? Barbara Ally explains: “not all artists are suited to working in a cross-disciplinary academic environment.”

- Which units could provide funding? In our experience, these have included the Cultural Affairs Office, Student Services, and Chancellor’s Office. State Arts Commissions often support projects of this type. Make sure to involve your Development Office and research state or federal grants.

It is our hope to show a path in which multi-disciplinary projects can be successful from a marketing and communications standpoint as well as from an artistic and educational point of view. In the first section, we interviewed Marvin Stamm, a classically-trained jazz musician who has successfully crossed the bridge between musical disciplines with high artistic standards. We explored his basic philosophy as well as some of the obstacles that he had to overcome and invited him to describe specific musical examples from the different projects he participates where cross-disciplinary sensitivity is essential, especially in “The Twain Have Met” by Greg McLean. We then explored some of the academic and educational benefits of cross-disciplinary projects. The references to current initiatives and research provide strong arguments that can be used to engage senior faculty and administration. Finally, we interviewed performing arts presenters with consummate experience in such innovative endeavors. They generously shared their wisdom on the critical aspects to be considered for cross-disciplinary projects to succeed.

One could make the argument that all truly great artists of our time have engaged in cross-disciplinary creation in some form or another. By looking at this issue from multiple angles, we embark on an exploration of some of the intrinsic differences between crossover music that substantially enriches our life (i.e. Ravel’s Blues movement from the Second Violin Sonata) and works that thrill but do not nourish the soul (i.e. Vieuxtemps’ “Variations on the American Yankee Doodle”). Marvin Stamm, perhaps, best addresses this issue when he comments, “The music itself will dictate direction and style, and the performer will interpret it.” This remains the core of artistic integrity—an attitude of service toward the music. It is the elusive glue that binds and makes possible the perfect combination of educational, financial, and academic objectives. When lacking, one or more of these areas will fall behind. When present, the possible benefits for music teachers and students are considerable.

Editor's Note: Many thanks to those who generously gave of their time to make this article possible, including the presenters and programming directors interviewed throughout the paper, trumpeter Marvin Stamm, and Dr. Michael J. Budds, Curators’ Professor of Musicology at the University of Missouri.

Endnotes

1Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, trans. H. F. Cary, illust. Gustave Doré (New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1909).

2The Music Center is one of the largest performing arts centers in the United States. Located in Los Angeles, CA, it is the umbrella institution for the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Ahmanson Theater, Mark Taper Forum, and Walt Disney Concert Hall and its resident companies: the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, Los Angeles Master Chorale, and Center Theatre Group.

3Music Arts Management (MAM) is based in Knoxville, TN and was founded in 2010. The artists on its roster are not only outstanding performers but also leading educators in both jazz and classical idioms. The company’s mission is to bridge the gaps between music academia and industry while providing creative opportunities for artistic and scholarly collaboration.

4Disclosure: Marvin Stamm is represented by Music Arts Management.

5[Photograph of Stan Kenton, Marvin Stamm, Gabe Baltazar, Dee Barton, and Jim Amlotte]. UNT Digital Library. http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc11429/. Accessed July 26, 2013.

6Author’s note: To broaden the performance possibilities, composer Greg McLean also orchestrated the concerto for wind ensemble, and it is now available in both formats. The publisher of both editions is Editions-BIM. Sheet music is available from them here.

7Greg McLean, The Twain Have Met, perf. Marvin Stamm, Cathy Leach, University of Tennessee Symphony Orchestra, cond. James Fellenbaum. February 17, 2008.

8Greg McLean, The Twain Have Met, perf. Marvin Stamm, Cathy Leach, University of Tennessee Symphony Orchestra, cond. James Fellenbaum. February 17, 2008.

9http://www.vanderbilt.edu/curbcenter/mike-curb/

10Harvey Burrell, “Getting Unplugged.” Idea Blog, The Curb Center for Art, Enterprise, and Public Policy (14 August 2013). Retrieved 21 September, 2013 from http://www.vanderbilt.edu/curbcenter/mike-curb/?page_id=2139

11Stern, M., quoted in Alan S. Brown and Steven J. Tepper, “Placing the Arts at the Heart of the Creative Campus.” Association of Performing Arts Presenters (December 2012), 8. Retrieved 21 September, 2013 from http://www.apap365.org/KNOWLEDGE/Seminars/Documents/Creative %20Campus%20White%20Paper%20w%20Exec%20Sum.pdf.

12Long Lingo, E., Taylor, A., Lee, C., quoted in Ibid., 9.

14“Team Science,” National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Retrieved July 1, 2013 from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/researchfunding/grant/strategy/pages/2teamscience.aspx.

15Dan Berrett, “Creativity: The Cure for a Common Curriculum.” The Chronicle of Higher Education (1 April 2013). Retrieved June 15, 2013 from https://chronicle.com/article/The-Creativity-Cure/138203.

17Stan Kenton was a precursor of this trend, but since then many composers (i.e., Gunther Schuller, Thelonious Monk, David Baker, Ran Blake, John Lewis) and performers (Ornette Coleman, Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, Allen Vizzutti, Marvin Stamm, to name a few) have explored this area. See Gunther Schuller, Musings: The Musical Words of Gunther Schuller (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).