Abstract

While music educators and administrators have increasingly voiced support for improvisation as an integral component of music education in recent decades, research reveals a continuing discrepancy between this viewpoint and evidence of improvisation in music education curricula outside the jazz idiom. Studies investigating the challenges of integrating improvisation highlight the importance of providing improvisational experiences in collegiate-level performance and academic courses, as well as offering improvisation teaching techniques in undergraduate methods classes. This study examines the extent to which improvisation is currently incorporated into collegiate music curricula. Sixty-one music faculty members presently teaching in twelve institutions across the United States completed an online survey regarding course offerings specifically devoted to improvisation, and the extent to which courses they teach include improvisation. Of all the respondents, 75% reported teaching at an institution that offers a course specifically devoted to improvisation and that all respondents who teach music methods courses include some improvisation. However, aside from those teaching courses related to jazz, 80% of respondents incorporate improvisation either not at all or less than 15% of the time. This investigation suggests that continued discussion regarding the integration of varying forms and degrees of improvisation throughout collegiate music curricula remains necessary.

Introduction

Most music educators agree that improvisation is a valuable component in music education and support its inclusion in the National Content Standards for Music Education.1 However, studies investigating the implementation of National Content Standard 3—improvising melodies, variations, and accompaniments—reveal that it continues to be one of the least integrated areas into school music curricula.2 Both music education faculty and music educators have consistently cited it as the most difficult standard to implement and identify it as an area with which they are least comfortable.3 Research reveals that a lack confidence in improvising ability and ability to teach improvisation as primary reasons that have discouraged and inhibited educators from including improvisation comprehensively into their instruction.4

This sentiment is not surprising given that most musicians formally trained through the educational system have generally had very little background in improvisation.5 Music instruction has come to focus primarily on developing the ability to read and re-create music from written notation as compared to incorporating aural and creative skills such as improvisation or composition.6 Musicians are bound to what McPherson refers to as a visual orientation to music-making.7 Kushner states that “all but those few are virtually incapacitated in constructing music as they go along—they have been inducted into a relationship of dependency.”8

Consequently, calls for a more comprehensive approach to music education incorporating improvisation have continued over the years to little effect. As Shuler points out, teachers generally teach how they were taught, and are “unlikely to emphasize, teach, or even, in many cases, value what they are not comfortable modeling themselves.”9 In light of this, Hickey appropriately poses the question, “Where and how will future teachers learn to break the cycle?”10

Many have argued that the answer lies in university teacher preparation programs. Researchers have consistently emphasized the need for collegiate music education programs to adapt curricula to address each of the nine National Content Standards, particularly if future educators are to be equipped with the necessary background, skills, and confidence to successfully teach the competencies called for by the National Standards.11 If music teachers are expected to include improvisation in their teaching, is it not reasonable to expect that teacher-training programs would provide rich improvisational experiences and pedagogical strategies for teaching improvisation?

Reasonable as it may seem, it appears that this has not been the case. The research examining music educators’ pre-service experience and preparedness to teach and implement improvisation shows that opportunities for improvisation at the college level are infrequent, even throughout teacher preparation programs. Often, students whose studies involve jazz, Dalcroze, or Orff pedagogy are the only few who are exposed directly and regularly to the concept and practice of improvisation.12 To further investigate the presence of improvisation throughout higher education music curricula, this study examined the extent to which improvisational opportunities and improvisation pedagogy were being incorporated in collegiate-level performance and academic courses. Two research questions were addressed:

1. To what extent do collegiate music faculty in the United States integrate improvisation into their teaching?

2. In which courses is improvisation most and least likely to be found?

Related Literature

Five years following the establishment of the National Content Standards for Music Education in 1994, Fonder and Eckrich found that the impact of the national standards on collegiate music teacher education curricula was most evident in the country’s largest music schools.13 Though results from this study indicated greater curricular attention was being given to improvisation, composition, and world music, other contemporary studies revealed otherwise. Wollenzien analyzed curriculum content in undergraduate music education programs of the north central United States. Survey results revealed that topics related to improvisation or improvisation pedagogy were not being covered in many higher education institutions.14 Similarly, Abrahams identified improvisation as one of the weakest areas even in two university programs documented as successfully aligning their curricula to the Standards.15

Later studies did not reflect much progress. Forsythe, Kinney, and Braun investigated the attitudes and views of both music education faculty and pre-service music students towards the National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) standards for music teacher education. Results showed that improvisation was considered to be one of the least important for competent music teaching.16 The study concluded that Content Standard 3 remained unaddressed relative to the other standards at all levels.17

Other studies examined perceptions of both music education faculty and their graduates but focused on the extent to which courses in music education were sufficiently preparing future teachers to teach the National Standards. Faculty surveyed in Adderley, Schneider, and Kirkland felt that their courses should enable students to effectively implement the national standard on improvisation; on the contrary, the 941 K-4 educators throughout the United States surveyed in the study reported that their coursework “provided below average preparation in teaching students how to improvise melodies, variations, and accompaniments.”18 The authors concluded that preparation for implementing Content Standard 3 needed serious consideration. Similarly, Johnson focused on the music theory preparation of music education majors in all NASM-accredited programs in four-year institutions in Texas. Survey data from 103 music theory faculty members teaching in 33 participating institutions revealed that improvisation was largely absent from the music theory curricula.19

A more recent study to focus on the teaching of musical improvisation at the university level specifically looked at general music methods course instructors’ experiences, approaches, and perspectives on the topic. Results from 42 participants surveyed indicated that while 93% included improvisation within their curriculum, half of them (n = 21) spent 10% of class time on improvisation; the remaining 14 (33%) spent 20% of class time, and only two spent 40% or more of class time on improvisation.20 These findings are in line with other research that suggests that courses in teacher preparation curricula do not adequately address improvisation.

In 2005, Whitcomb surveyed 281 randomly selected elementary general music teachers in the state to investigate teacher attitudes towards, background in, and implementation of improvisation.21 Results from data collected through questionnaires revealed that while 87% of respondents incorporated some form of improvisation in their classrooms, those who did so still reported lack of instructional time and experience in improvising as the predominant factors inhibiting them from more regularly incorporating improvisation into their teaching. The study found “a significant relationship between classroom implementation of improvisation and teachers’ reported training at professional workshops and conferences,” and recommended the incorporation of improvisation teaching techniques in undergraduate methods classes, the inclusion of more improvisational experiences for future teachers in undergraduate music offerings, and an increase in professional development opportunities devoted to improvisation.22

In light of such recommendations by Whitcomb and others, some researchers have focused on the efficacy of methods courses and professional development opportunities on educators’ attitudes and confidence. Bell’s study investigated the effect of a sixteen-week graduate level course exploring the standards, designing teaching strategies, and practicing implementation of materials on New York State certified K-12 music teachers, currently in the classroom. The course’s positive impact was evident as 64% acknowledged changes in their “present” teaching, 36% expressed that studying the music standards would effect “future” teaching, and 29% recognized a change in attitude towards standards, reflecting an increase in both awareness and openness to incorporating them in their teaching.23 While 36% of the participants identified improvisation (Standard 3) as the most difficult to implement, 21% specifically mentioned that they desired additional training in implementing improvisation even after the course.

These results corroborated two earlier studies. Campbell and Della Pietra examined the impact of a five-week improvisation-training segment embedded within a required methods course on improvisation skills and teaching techniques. At the end of the study, participants had gained considerable awareness of and confidence in improvisation teaching techniques.24 Likewise, Froseth found a 25% increase in perceived preparedness to teach improvisation following undergraduate coursework that focused on each of the Standards and provided improvisational instruction.25

Additionally, two studies by the same researcher investigated music teacher confidence in implementing improvisation with similar results. In 2000, Madura surveyed vocal jazz improvisation conference session participants (N = 81). Teachers rated their confidence in teaching improvisation as outlined by the National Standards. Results showed “moderate confidence” in teaching elementary school standards, “slight confidence” to teach 5th through 8th grade standards, and “almost no confidence” in teaching high school standards.26

Seven years later, Madura Ward-Steinman set out to replicate the earlier study on a larger, more international scale using participants (N = 213) at six vocal jazz improvisation workshops at state, national, and international conferences between 2004 and 2006.27 Using the same questionnaire as in the earlier study, the participants (including general music teachers and elementary, middle and high school choral music teachers) were asked to rate their own confidence levels in teaching improvisation, their abilities as improvisers, and their interest in learning more about improvisation and improvisation pedagogy. Findings were in line with the earlier study. Confidence levels declined as the grade level of the standard increased. Respondents from both studies reported low self-ratings in regards to improvisation ability, but expressed high interest in improvisation pedagogy.28

Part two of the study involved an intensive six-week course in vocal jazz that included research-based improvisation instruction, which significantly improved music education undergraduate students’ confidence in teaching improvisation. Again, participants expressed a high level of interest in learning more about improvisation and improvisation pedagogy, supporting the notion that professional development workshops and methods courses have the potential to significantly alleviate apprehension towards improvisation.29

If, as many suggest, the key to significant change towards greater implementation of improvisation lies with university music education programs, it would be worthwhile to specifically examine the extent to which improvisation is occurring in collegiate music courses. While many studies have measured the level of improvisation in elementary schools, less research has been done at the college level.

Method

This study examined the extent to which improvisation is currently being incorporated into collegiate music curricula. For the purposes of this study, “improvisation” was defined as the spontaneous creation of original music rhythmically, melodically, or harmonically. An invitation and link to a researcher-designed online survey through SurveyMonkey.com was emailed to 417 adjunct and full time music faculty members presently teaching at 12 institutions across the country. The institutions were randomly selected by stratified sampling according to geographic location and size. Prior to sending out the survey, two field trials of the survey were conducted to determine the clarity and quality of the questions as well as the average time for completion.

The survey asked participants to measure the extent to which courses they taught in the last five years included improvisation according to the following categories: (a) none, (b) less than 15%, (c) 15-40%, (d) 40-70%, and (e) more than 70%. Additional research questions were whether their institution offered courses specifically devoted to improvisation, how long they had been teaching at the college level, how many music majors attended their institution, and what percentage of the music students were specifically music education majors. The final section offered participants an optional opportunity for comments.

Results

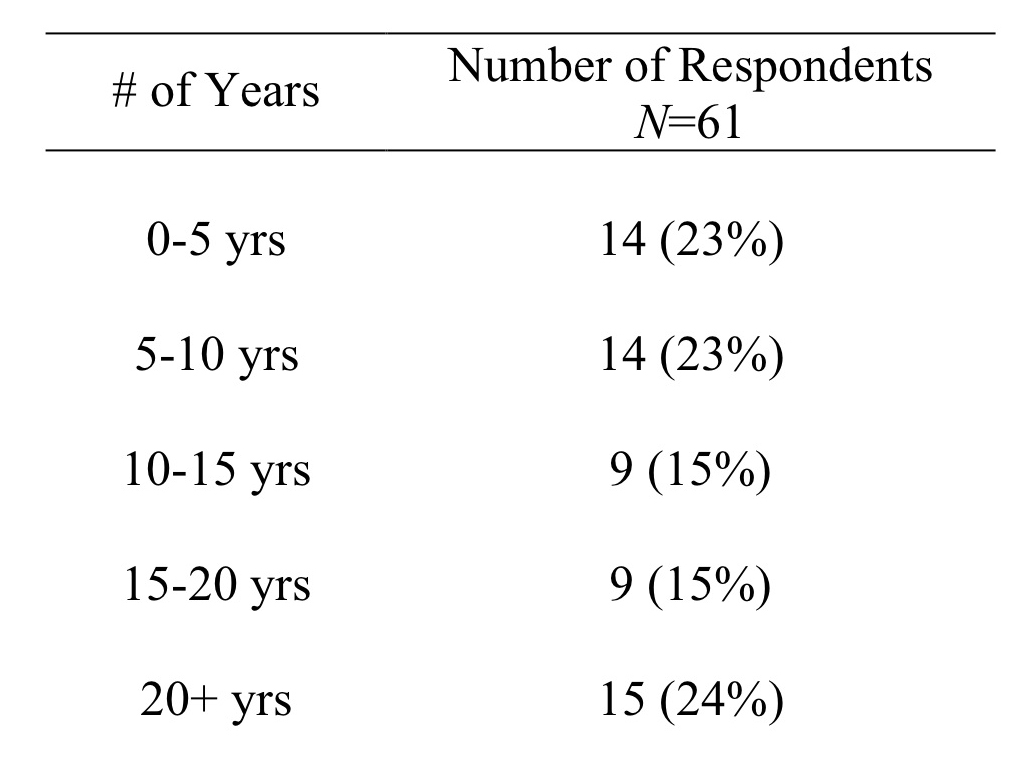

A total of 61 faculty members responded voluntarily for a response rate of 15%, which is considered typical for external surveys.30 Respondents represented a wide range of college teaching experience and were relatively equally distributed throughout the spectrum (see Table 1). Of the 61 respondents, 47 (77%) reported teaching two or more courses, and 22 (36%) indicated teaching in both performance (ensembles, applied/group lessons, aural skills) and academic (music history, theory, methods, music appreciation) areas.

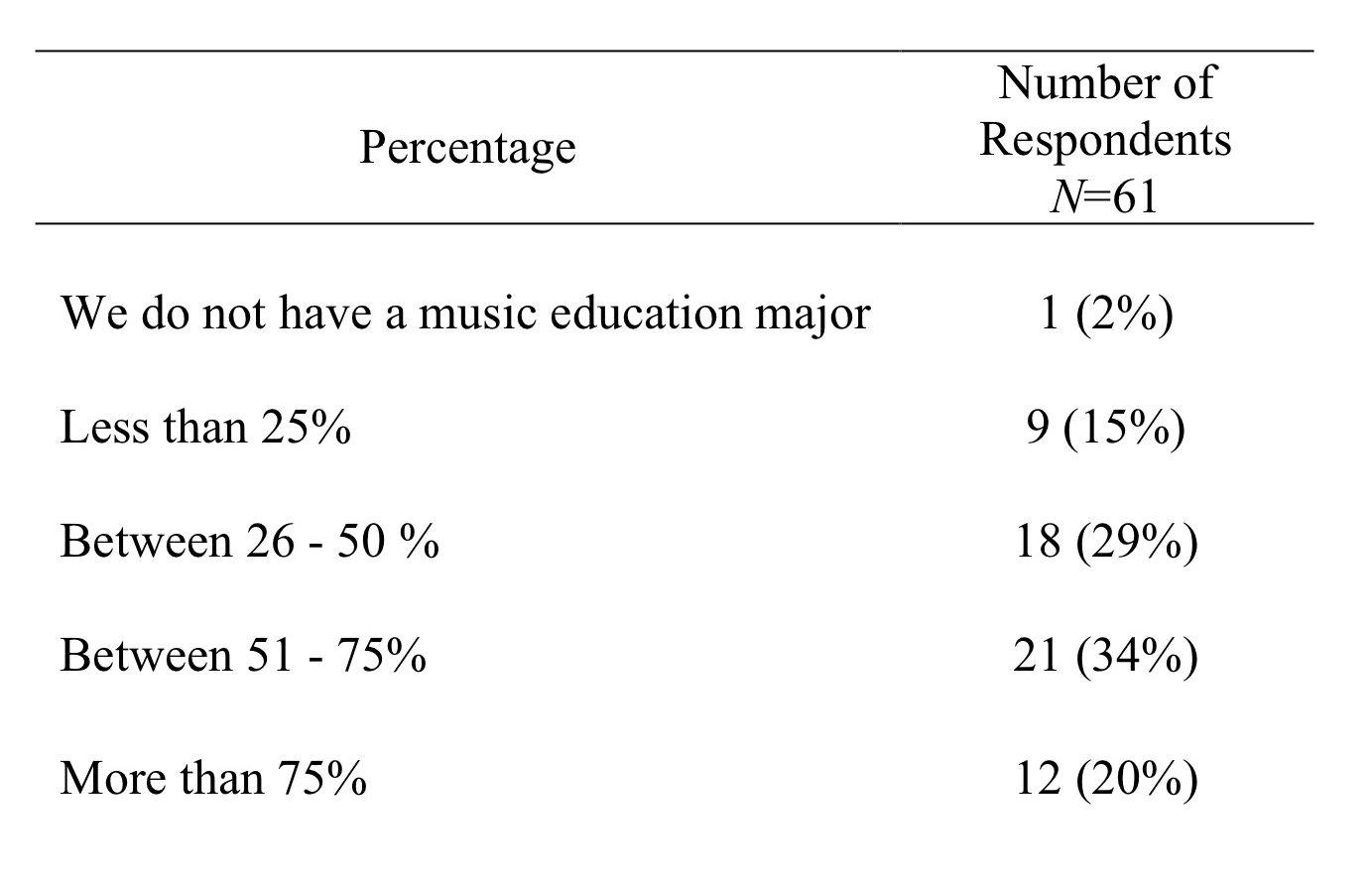

More than half of the participants represented large music schools with 62% reporting that they teach at an institution with over 200 music majors while 18% teach at a medium size institution with 100-200 music majors, and 20% at a small institution with less than 100 music majors. Table 2 shows the percentage of music students reported as specializing in music education. Only one respondent reported not having a music education major at their institution.

Forty-five respondents (74%) reported that their institution offered a course specifically devoted to improvisation. Of this number, only six (13%) indicated that such a course was required of music education majors. One mentioned that an improvisation course was offered but only required for jazz students and not for music education majors. Seven (11%) indicated that their institution did not offer such a course, and nine (15%) did not know for sure.

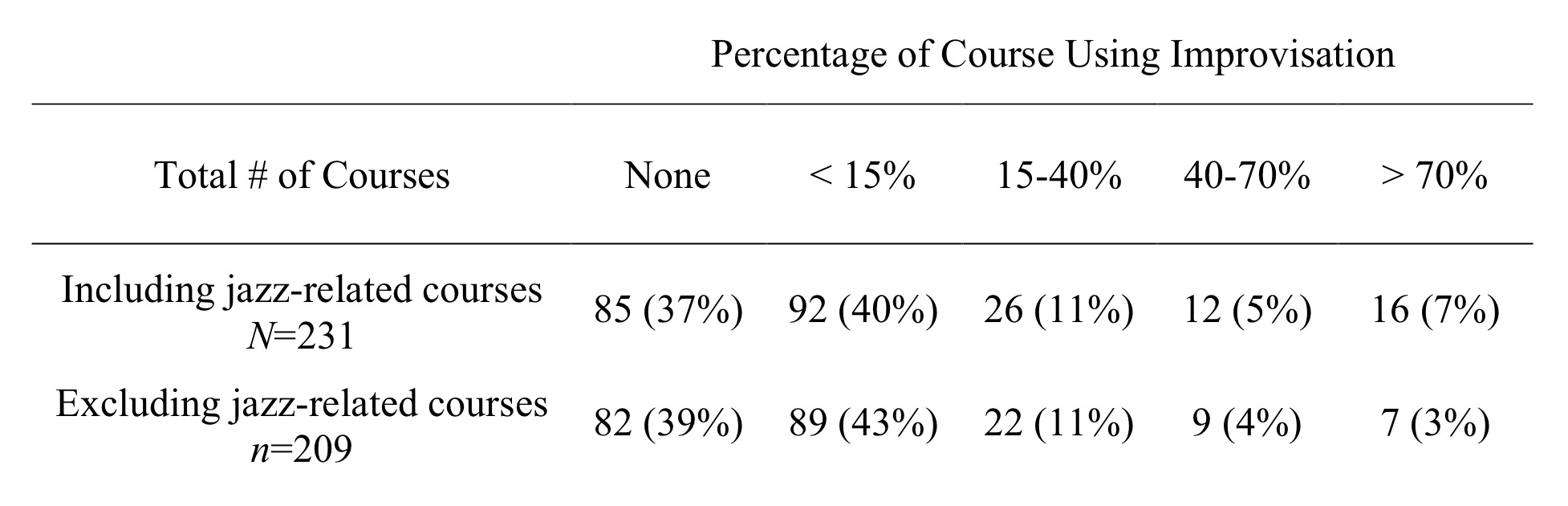

An examination of the survey results revealed that 61 respondents taught a total of 231 courses within the last five years. Of the 231 courses, 22 (10%) of the courses were jazz related (jazz choir, jazz band, or jazz studies; this number excludes applied lessons which may include those specifically oriented towards jazz, such as jazz guitar, etc.). Of the 209 non-jazz related courses, 109 (47%) were performance related (ensembles, applied/group lessons, aural skills) and 100 (43%) were academic courses (music history, theory, methods, music appreciation). Given that improvisation is often inherent in jazz education, results in this study are presented in two ways: including and excluding courses related to jazz.

For each course taught, participants reported the extent to which improvisation is used in the course according to the following categories: (a) none, (b) less than 15%, (c) 15-40%, (d) 40-70%, and (e) more than 70%. Table 3 shows the total number of reported courses for each percentage category both including and excluding jazz courses.

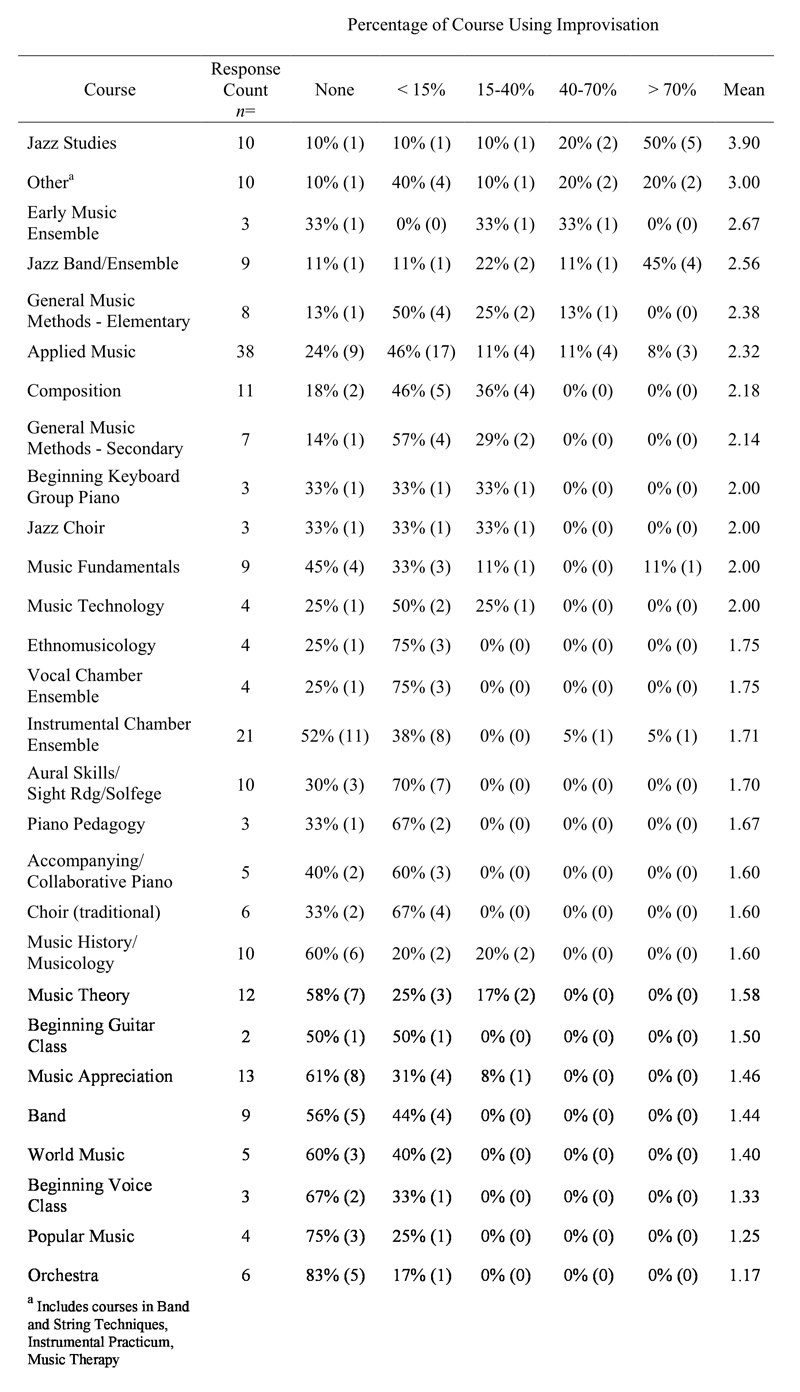

Table 4 presents the extent to which improvisation is used in courses commonly offered in collegiate music programs, as reported by the faculty surveyed. A five-point scale was used to measure the extent of improvisation for each course, ranging from none (1) to more than 70% (5). Results are presented in descending order beginning with courses using the most improvisation to those using the least.

Non jazz-related courses reported to use the most improvisation were Early Music Ensemble (M = 2.67) and Elementary Music Methods (M = 2.38) with 38% using improvisation more than 15%. Conversely, improvisation is least used in Orchestra (M = 1.17) with 83% using none, followed by Popular Music (M = 1.25) with 75% using none.

Survey respondents had the opportunity to mark “Other” if their course was not listed. Of the ten participants who did so, five specified the missing course under comments: two participants mentioned Band Techniques, one participant mentioned String Techniques, one mentioned Instrumental Practicum, and one mentioned Music Therapy. The other five did not specify.

Discussion

Results of this study suggest that improvisation remains predominantly absent from many collegiate music courses. Excluding jazz related courses, a majority (82%) of the 209 courses do not incorporate any improvisation, or do so less than 15% of the time. This finding is similar to Rinehimer’s study, which found that half of the instructors included improvisation only 10% of the time.31 However, 45 respondents (74%) reported that courses specifically devoted to improvisation were offered at their institution. Though 87% indicated that it was an elective and not required of music education majors, this finding suggests that opportunities to learn about improvisation may be more readily available than before.32

As was expected, improvisation is most prevalent within the jazz idiom, as 73% of jazz related courses use improvisation more than 15% of the time, compared to only 18% of all non-jazz related courses. Improvisation was seemingly more widespread in jazz band/ensemble than in jazz choir. What was most surprising was that both jazz ensemble and jazz choir each had one respondent reporting the use of no improvisation.

Two out of three early music ensembles were reported to incorporate improvisation more than 15% of the time. Though one indicated not using any improvisation, the overall mean (M = 2.67) suggests that given improvisation remained a primary aspect of performance in the Western European classical tradition well into the nineteenth century,33 it is being emphasized and explored in the name of historic performance practice.

Interestingly, the survey results suggest that performance courses (e.g., ensembles, applied/group lessons, and aural skills) use slightly less improvisation than academic courses (e.g., music history, theory, methods, and music appreciation), with 83% of performance courses using no improvisation or less than 15% of the time, compared to 77% of the academic courses that do not use improvisation or do so less than 15% of the time. Given that improvising is a performance-related activity, this was unexpected. A possible explanation might be that basic improvisational activities are less compatible with performance ensembles, which tend to be predominantly focused on preparing for performances at a high level. Furthermore, a lack of time—often an issue for ensemble directors as well as applied lessons instructors, who too are pressured to prepare their students for public performances, auditions, and competitions—may be a discouraging factor.

Of the academic courses surveyed, methods courses were reported to include the most improvisation, with slightly more use in elementary level general music methods courses (M = 2.38) than at the secondary level (M = 2.14). This difference between the two levels is in line with Rinehimer, who found that faculty teaching secondary level music methods did not address the more advanced achievement standards for improvisation, and that “formal improvisation instruction, although valued by teachers, was rare in the curriculum except perhaps in methods course geared for young children.”34 Though the total number of methods courses comprised just 7% of the total number of courses reported for this study, this finding supports other researchers who have noted that the methodologies of Orff-Schulwerk and Dalcroze, which are primarily associated with elementary music education, are one of the few domains that commonly employ improvisation.35

The indication that applied lessons (M = 2.32) are incorporating improvisation nearly as much as jazz ensembles (2.56) must be considered carefully. Three of the applied instructors reported the use of improvisation more than 70% of the time during their teaching of guitar, saxophone, and percussion lessons. These same instructors also reported that they teach jazz studies. Consequently, their focus on improvisation during individual lessons would be expected. If the mean for Applied Music is recalculated without these three instructors, the result has a new mean of 1.92, which falls below the median (Mdn = 2.54). In light of the historical background of organ improvisation, it is also worth noting that one organ instructor reported using improvisation 40-70% of the time.

The response rate of 15%, though average for external surveys, was disappointing, and may indicate that the topic of improvisation is not a priority for music faculty. One respondent wrote under comments that “The importance of improvisation in the music curriculum is currently over emphasized.” This sentiment echoes the point of view suggested in Lehman’s study that the improvisation standard “should be de-emphasized or deleted.”36 Likewise, 12% of the respondents in Whitcomb’s study surveying 144 elementary general music educators in Illinois felt that improvisation should no longer remain in the National Standards for Music Education, while 19% did not know.37

Conclusions and Implications for Music Education

This study reveals that the use of improvisation in higher education outside the jazz curriculum remains minimal and highlights the need for continued discussion regarding the integration of varying forms and degrees of improvisation throughout collegiate music curricula. A majority of the collegiate music faculty in the United States is not integrating improvisation into their teaching, or doing so in less than 15% of the time. Not surprisingly, jazz courses use the most improvisation. Outside the jazz idiom, early music ensembles and Elementary Music Methods appear to integrate improvisation the most. Conversely, Orchestra and Popular Music were reported to use the least amount of improvisation.

In order to generalize to a broader population, a wider, more comprehensive sample of university instructors should be surveyed. The low response rate in this study may limit its reliability. A higher response rate might be achieved by disseminating the survey through organizations such as College Music Society or NASM rather than through the researcher’s individual email. Initiating personal contact with heads of music schools and departments to request participation in and support of the study prior to sending out the survey to their faculty may also improve the response rate. When replicating this study, one should also consider a broader course list that includes areas in Music Therapy, Band and Choral Methods, Instrumental Techniques, and Instrumental Practicum.

Music programs in higher education are in a unique position to directly impact the next generation of musicians and music educators. As such, they must offer an integrated approach whereby improvisation is explored in various content areas across the curriculum. Music teacher preparation programs must specifically explore and address the value of improvisation through courses focused on the art of improvisation and improvisation pedagogy. The incorporation of improvisational activities in both performance and academic courses throughout pre-service music teacher programs would also enhance the confidence and ability of educators to teach and incorporate improvisation. A concerted effort by administrators, faculty in higher education, music education organizations, and music educators is necessary if we are to break the cycle and ground improvisation as an essential, evident component to musical training.

Table 1. College Teaching Experience

Table 2. Percentage of Music Students Specializing in Music Education

Table 3. Total Number of Courses in Each Percentage Category

Table 4. Extent of Improvisation Reportedly Used in Each Course

Notes

1For benefits and unique value of improvisation see Allsup, “Active Self-Transformation,” 81; Dobbins, “Improvisation: An Essential Element,” 41; Hargreaves, “Developing Musical Creativity,” 28; McPherson, “Redefining the Teaching,” 59; Moore, “The Decline of Improvisation,” 66; Rinehimer, “Teaching Improvisation.” For support as a National Standard by high school band instructors in New York state, see Schopp, “A Study of the Effects of National Standards,” 156. For support by elementary general music teachers in Illinois, see Whitcomb, “Descriptions of Improvisational Activities,” 119.

2Orman, “Comparison of the National Standards,” 162. See also Pignato, “An Analysis of Practical Challenges,” 13; Schopp, “A Study of the Effects of National Standards,” 177; Whitcomb, “Elementary Improvisation,” 33.

3Adderley, Schneider, and Kirkland, “Elementary Music Teacher Preparation,” 3; Froseth, “The Standards,” 40.

4Bell, “Beginning the Dialogue,” 37; Byo, “Classroom Teachers,’” 119; Lehman, “A Vision for the Future,” 30; Madura, “Vocal Music Directors’ Confidence,” 33; Madura Ward-Steinman, “Confidence in Teaching Improvisation,” 26; Whitcomb, “Descriptions of Improvisational Activities,” 122.

5Shuler, “The Impact of National Standards,” Key Principles section, para. 2.

6Hargreaves, “Developing Musical Creativity,” 28.

7McPherson, “Redefining the Teaching,” 57.

8Kushner, “Falsifying (Music) Education,” 11.

9Shuler, “The Impact of National Standards,” Key Principles section, para. 2.

10Hickey, “Can Improvisation Be Taught,” 296.

11Abrahams, “National Standards for Music Education,” 27; Adderley, “Music Teacher Preparation,” 191; Adderley, Schneider, and Kirkland, “Elementary Music Teacher Preparation,” 16; Froseth, “The Standards,” 59; McCaskill, “The National Standards,” 2; Shuler, “The Impact of National Standards,” para. 4.

12Abrahams, “National Standards for Music Education,” 28; Shuler, “The Impact of National Standards,” Improvisation section, para. 2.

13Fonder and Eckrich, “A Survey on the Impact of the Voluntary National Standards,” 36.

14Wollenzien, “An Analysis of Undergraduate Music,” iii.

15Abrahams, “Implementing the National Standards,” 212. The two institutions were Cathedral University and Chapel College.

16See also Johnson, “Competencies, Curricula, and Compliance,” 51; music theory faculty ranked improvisation ability near last - 26th out of 28 competencies for music teachers in primary and secondary schools.

17Forsythe, Kinney, and Braun, “Opinions of Music Teacher Educators,” 24.

18Adderley, Schneider, and Kirkland, “Elementary Music Teacher Preparation,” 8.

19Johnson, “Competencies, Curricula, and Compliance,” 72. Of the 33 institutions in Texas examined, only only two included "improvisation" in the course description of a lower level required theory course, 70.

20Rinehimer, “Teaching Improvisation,” 51.

21Whitcomb, “Descriptions of Improvisational Activities,” 72.

23Bell, “Beginning the Dialogue,” 35. See also Riley, “Pre-Service Music Educators’ Perceptions.”

24Della Pietra and Campbell, “An Ethnography of Improvisation,” 117.

25Froseth, “The Standards,” 57.

26Madura, “Vocal Music Directors’ Confidence,” 36.

27Madura Ward-Steinman, “Confidence in Teaching Improvisation,” 31.

28Ibid., 34. See also Bernhard, “Music Education Majors’ Confidence in Teaching Improvisation,”69.

30Flagg, “Online Surveys,” http://www.howto.gov/customer-experience/collecting-feedback/online-surveys-fact-sheet. See also Rosen, “Increase Response Rate” http://survey.cvent.com/blog/best-practices-for-online-survey-creation/increase-response-rate-by-further-legitimizing-your-survey-v2

31Rinehimer, “Teaching Improvisation,” 51.

32Prior studies indicate collegiate music programs offer limited experiences in improvisation. See Adderley, Schneider, and Kirkland, “Elementary Music Teacher Preparation,” 8; Fonder and Eckrich, “A Survey on the Impact of the Voluntary National Standards,” 36; Ronald B. Thomas, “Musical Fluency: MMCP and Today's Curriculum,” 27; and Wollenzien, “An Analysis of Undergraduate Music,” iii. For a more recent study highlighting a music degree program offering courses in improvisation, see Bernhard, “Music Education Majors’ Confidence,” 68.

33Moore, “The Decline of Improvisation,” 63.

34Rinehimer, “Teaching Improvisation,” 63.

35Abrahams, “National Standards for Music Education,” 28; Shuler, “The Impact of National Standards,” improvisation section, para. 2.

36Lehman, “A Vision for the Future,” 30.

37Whitcomb, “Descriptions of Improvisational Activities,” 103.

Bibliography

Abrahams, Frank E. “Implementing the National Standards for Music Education in Pre-service Teacher Education Programs: A Qualitative Study of Two Schools.” PhD diss., Temple University, 2000a. ProQuest (AAT 9965947).

—. “National Standards for Music Education and College Preservice Music Teacher Education: A New Balance.” Arts Education Policy Review 102, no. 1 (2000b): 27-31.

Adderley, Cecil L. “Music Teacher Preparation in South Carolina Colleges and Universities Relative to the National Standards: Goals 2000.” PhD diss., University of South Carolina, 1996. ProQuest (AAT 9711655).

Adderley, Cecil L., Christina Schneider, and Norma Kirkland. “Elementary Music Teacher Preparation in U.S. Colleges and Universities Relative to the National Standards - Goals 2000.” Visions of Research in Music Education 7 (2006): 1-17.

Allsup, Randall E. “Activating self-transformation through improvisation in instrumental music teaching.” Philosophy of Music Education Review 5, no. 2 (1997): 80-85.

Bell, Cindy L. “Beginning the Dialogue: Teachers Respond to the National Standards in Music.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 156 (2003): 31-42.

Bernhard, Christian H. “Music Education Majors’ Confidence in Teaching Improvisation.” Journal of Music Teacher Education 22, no. 2 (2013): 65-72.

Byo, Susan J. “Classroom Teachers' and Music Specialists' Perceived Ability to Implement the National Standards for Music Education.” Journal of Research in Music Education 47, no. 2 (1999): 111-123.

Della Pietra, Christopher J. and Patricia S. Campbell. “An Ethnography of Improvisation Training in a Music Methods Course.” Journal of Research in Music Education 43, no. 2 (1995): 112-126.

Dobbins, Bill. “Improvisation: An Essential Element of Musical Proficiency,” Music Educators Journal 66, no. 5 (1980): 36-41, doi:10.2307/3395774.

Flagg, Rachel. “Online Surveys.” GSA’s Office of Citizen Services & Innovative Technologies, last modified May 16, 2013, http://www.howto.gov/customer-experience/collecting-feedback/online-surveys-fact-sheet.

Fonder, Mark and Donald W. Eckrich. “A Survey on the Impact of the Voluntary National Standards on American College and University Music Teacher Education Curricula.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 140 (1999): 28-40.

Forsythe, Jere L., Dayrl W. Kinney, and Elizabeth L. Braun. “Opinions of Music Teacher Educators and Preservice Music Students on the National Association of Schools of Music Standards for Teacher Education.” Journal of Music Teacher Education 16, no. 2 (2007): 19-33.

Froseth, James O. “The Standards: Surveys of Undergraduate and Graduate Values.” In Aiming for Excellence: The Impact of the Standards Movement on Music Education, 45-60. Reston, VA: MENC, 1996.

Hargreaves, David J. “Developing Musical Creativity in a Social World.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 142 (1999): 22-34.

Hickey, Maud. “Can Improvisation Be Taught? A Call for Free Improvisation In Our Schools.” International Journal of Music Education 27, no. 4 (2009): 285-299.

Johnson, Vicky V. “Competencies, Curricula, and Compliance: An Analysis of Music Theory in Music Education Programs in Texas.” DMA diss., Boston University, 2010.

Kushner, Saville. “Falsifying (Music) Education: Surrealism and Curriculum.” Critical Education 1, no. 4 (2010). http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/criticaled/article/view/182240/182307.

Lehman, Paul. “A Vision for the Future: Looking at the Standards.” Music Educators Journal 94, no. 4 (2008): 28-32.

Madura, Patrice D. “Vocal Music Directors’ Confidence in Teaching Improvisation as Specified by the National Standards for Arts Education: A Pilot Study.” Jazz Research Proceedings Yearbook 2000 (2000): 31-37.

Madura Ward-Steinman, Patrice D. “Confidence in Teaching Improvisation According to the K-12 Achievement Standards: Surveys of Vocal Jazz Workshop Participants and Undergraduates.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 172 (2007): 25-44.

McCaskill, Lucinda L. “The National Standards for Music Education: A Survey of General Music Methods Professors' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Professional Practices.” PhD diss., University of Colorado, 1998. ProQuest (AAT 9827749).

McPherson, Gary E. “Redefining the Teaching of Musical Performance.” The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning 6, no. 2 (1995): 56-64.

Moore, Robin. “The Decline of Improvisation in Western Art Music: An Interpretation of Change.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 23, no. 1 (1992): 61-84.

Orman, Evelyn K. “Comparison of the National Standards for Music Education and Elementary Music Specialists' Use of Class Time.” Journal of Research in Music Education 50, no. 2 (2002): 155-164.

Pignato, Joseph M. “An Analysis of Practical Challenges Posed by Teaching Improvisation: Case Studies in New York State Schools.” PhD diss., Boston University, 2010. ProQuest (AAT 3430429).

Riley, Patricia E. “Pre-Service Music Educators’ Perceptions of the National Standards for Music Education.” Visions of Research in Music Education 14 (2009). http://users.rider.edu/~vrme/v14n1/vision/Riley%20Final2.pdf

Rinehimer, Bridget D. “Teaching Improvisation Within the General Music Methods Course: University Teacher Experiences, Approaches, and Perspectives.” Masters Thesis, Indiana University, 2012. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/handle/2022/15210.

Rosen, Dorian. “Increase Response Rate by Further Legitimizing Your Survey.” Web Surveys (Blog). http://survey.cvent.com/blog/best-practices-for-online-survey-creation/increase-response-rate-by-further-legitimizing-your-survey-v2

Schopp, Steven E. “A Study of the Effects of National Standards for Music Education, Number 3, Improvisation and Number 4, Composition on High School Band Instruction in New York State.” PhD diss., Teachers College, Columbia University, 2006. ProQuest (AAT 3225193).

Shuler, Scott C. “The Impact of National Standards on the Preparation, In-service Professional Development, and Assessment of Music Teachers.” Arts Education Policy Review 96, no. 3 (1995): 2-15.

Thomas, Ronald B. “Musical Fluency: MMCP and Today's Curriculum.” Music Educators Journal 78 (1991): 26-29.

Whitcomb, Rachel L. “Descriptions of Improvisational Activities in Elementary General Music Classrooms in the State of Illinois.” PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana Champagne, 2005. ProQuest (AAT 3199172).

—. “Elementary Improvisation in New York State: Survey Results.” School Music News 71, no. 2 (2007): 31–33.

Wollenzien, Timothy J. “An Analysis of Undergraduate Music Education Curriculum Content in Colleges and Universities of the North Central United States.” PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1999. ProQuest (AAT 9935017).