Introduction

Over the last several years the monetization of a revenue source through streaming for recording artists and labels has been in a state of flux. The sales of digital downloads continues to decline according to the 2013 Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) Music Industry Shipment and Revenue Statistics. The area of rapid digital growth is now in the area of new “‘access models’, where users can choose to listen from large libraries of music rather than purchasing individual songs or albums,” according to RIAA 2012 Statistics.

The acces, or "subscription-based," models already have several players (Pandora, Spotify, Rhapsody to name just a few), but these services are struggling to educate their listeners and to transfer them from “free” platforms to “paying” platforms. The latest subscription streaming service to throw their hat in the ring is Beats Music, launched on January 21, 2014, and purchased by technology giant Apple at the end of May, 2014, for $3 billion (Mangalindan, 2014).

This paper will examine how much recording artists and labels are being paid through streaming royalties, how profitable current streaming services are, and how Beats Music, with its team of music business veterans, intends to differentiate themselves through their latest version of the streaming subscription service.

Background

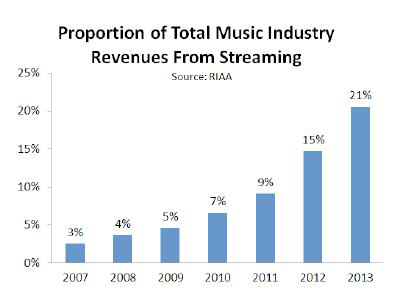

According to RIAA Statistics, access models have grown from 3% of the total recording industry revenues in 2007 to 21% in 2013.

Figure 1.

Total music industry revenue was $7 billion in both 2012 and 2013. Access models are an undeniably important player. The 21% of the market from streaming translates into over $1.4 billion distributed to performers and copyright holders as digital performance royalties. The royalties fall under three categories.

One category is covered by the statutory license, otherwise known as a neighboring right (for webcasting, satellite radio, and non-interactive digital music services). The royalties are collected and distributed by SoundExchange, a 501(c)(6) tax-exempt organization designated by the Copyright Royalty Board for this purpose. Radio services like Pandora and SiriusXM fall under this category. In 2012, Sound Exchange’s gross distributions were $462 million, a 58% increase over distributions of $372.2 million in 2011, according to their 2012 Annual Report. 2013 gross distributions as reported on the SoundExchange website were $590 million, a 28% increase over 2012.

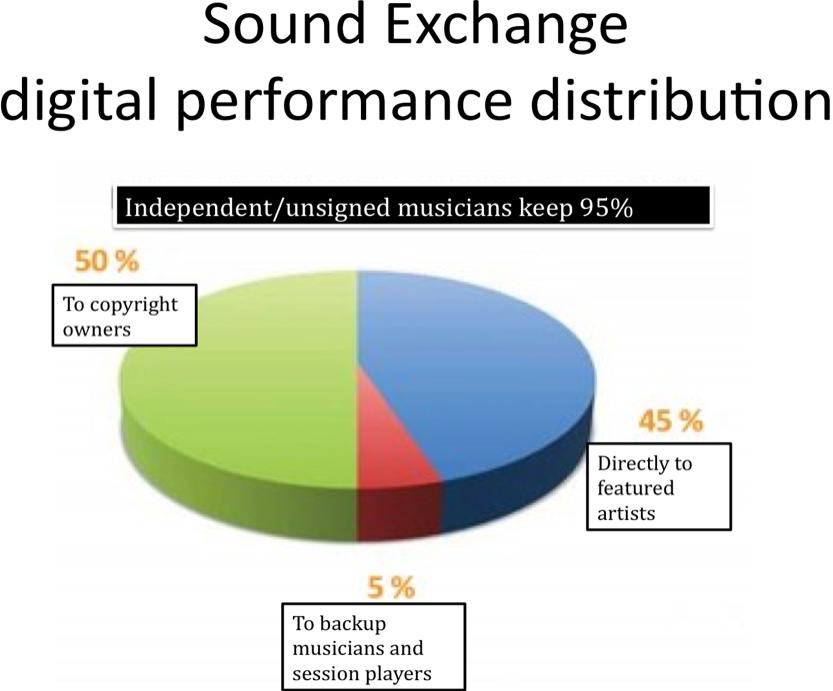

Sound Exchange has government-mandated percentages for distribution of digital performance royalties. According to the Sound Exchange website, under the law, 45 percent of performance royalties are paid directly to the featured artists on a recording, and 5 percent are paid to a fund for non-featured artists, typically session musicians and background singers. The other 50 percent of the performance royalties are paid to the owner of the sound recording (i.e., the owner of the “master”), which can be a record label or an artist who owns their own masters. (See Figure 2 below.)

Figure 2.

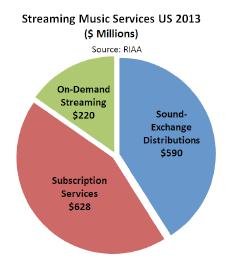

The other two categories are everything not covered by a statutory license (including subscription services such as Rhapsody and paid versions of Spotify, and non-subscription on-demand streaming services like YouTube, Vevo, and ad-supported Spotify). According to RIAA 2013 Statistics, revenues from these subscription and non-subscription on-demand streaming services were $628 million and $220 million respectively. The breakdown of these categories is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Clearly access models are being adopted by more listeners all of the time. There is no mandated percentage of digital performance royalties for these services as they are all negotiated. Generally, these services have to pay large fees upfront to major recording labels in order to have access to their catalogs; for example, Spotify paid $500 million in advances (Byrne, 2013). An artist’s portion received is usually based on royalty percentages in their recording contracts. Vestiges of the time when record companies bore the bulk of costs involved with physical production and distribution, contracts have not kept up with the digital age. Artists’ rates are around 8-15% on average (Fitzgibbon, 2013). The streaming payout rates (specifics discussed in the next sections) don’t amount to much, which explains why artists are receiving so little. But clearly, labels wouldn’t be granting licenses if they weren’t getting something out of the deal (Fitzgibbon, 2013).

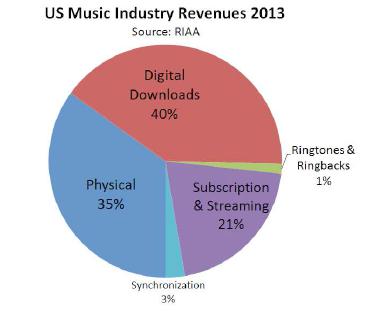

“Whether streaming has had any demonstrable effect on sales remains intensely debated” (Sisario, October, 2013). However, during the last quarter of 2013, Nielsen Soundscan reported digital downloads were down 4 percent from the same time in 2012 and RIAA 2013 Music Industry statistics reveal a decline of 1% to $2.8 billion of permanent digital downloads (including albums, single tracks, video and kiosk sales). Music executives were caught off guard when the rate of decline of downloads accelerated rapidly (Sisario, October, 2013). From current data, digital downloads comprise 40% (or $2.8 billion) of the $7 billion music industry, physical formats (largely CDs and some vinyl) take up 35% (or $2.4 billion) and the remainder is divided between synchronization and ringtone revenue. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

How Much Recording Artists and Labels Are Paid for Streaming

For listeners these days, sniffing out new music has never been easier, either through Spotify, doing a search on YouTube, or listening to Internet radio like Pandora or the newly launched iTunes Radio by Apple in Fall, 2013 (Caro, 2013). iTunes Radio is a free service with advertisements (Eaton, 2013). (Given that Apple recently purchased Beats does indicate that iTunes Radio wasn’t as successful as they wished.) The bottom line is, musicians want their music to be heard, but they are frustrated with the lack of royalties they receive (Caro, 2013).

Pandora’s rate for the song is about one-tenth of a penny per stream (.001), the money being split roughly 50/50 between the artist and label, which brings the artist’s take to .0005 cents per stream. Songwriting streaming payments go through the performing rights organizations, such as ASCAP or BMI, and generally their payout is even lower (Caro, 2013).

With Spotify, royalties are not government controlled, but based on direct licenses and agreements between its service and the copyright owner of the music, most often the label. None of these agreements are public and they can vary. Spotify plays songs on demand, rather than from a larger playlist, and their distributions per stream are a bit higher than Pandora’s. Spotify’s artist royalties amount roughly to about a quarter or a third of a cent per stream (.0025 or .0033) (Caro, 2013). (Spotify also requires musicians to go through an aggregator or label – an individual cannot simply submit their work).

However, on-demand streaming does pay, where piracy doesn’t (Fitzgibbon, 2013). And isn’t finding new revenue streams the point? A common defense of streaming from the labels is that while it takes longer to reap the equivalent of a download in royalties from streaming, once that critical point is reached, more royalties are generated with each stream (Lindvall, 2014).

Let’s look at some specific examples. For a band of four people that make a 15% royalty from Spotify streams, 236,549,020 streams would be needed for each person to earn a minimum wage of $15,080 per year. (Actually, 236,549,020 streams x .0025 x .15/4 equlas $22,176 per year, so perhaps the number could be slightly larger.) Granted, it would be assumed they would be receiving income from a variety of revenue producers, but given that download sales are moving downward and streaming is amping up, these numbers illustrate just how many streams are needed to make an impact.

David Lowery (Camper van Beethoven and Cracker) wrote a song entitled “My Song Got Played on Pandora 1 Million Times and All I Got Was $16.89, Less Than What I Make from a Single T-shirt Sale” (Byrne, 2013)! The 2013 summertime hit song, Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky,” reached 104,760,000 Spotify streams by the end of August. This translates to $13,000 each for the two band members of Daft Punk. Not a shabby sum, but this is a hit song from an extremely expensive recording. The majority of artists lack international hit songs, so where does this leave them (Bryne, 2013)? (The math for this $26,000/104,760,000 streams translates to .000248 per stream, less than 1/100th of a penny.)

In October of 2013, Thom Yorke of Radiohead said “As musicians, we need to fight the Spotify thing” and he pulled his latest band Atoms for Peace’s album from the streaming library (Fitzgibbon, 2013). On the opposite end of the spectrum, English singer-songwriter/activist Billy Bragg defended the site on Facebook while on tour in Sweden (home country of Spotify). “I’ve long felt that artists railing against Spotify is about as helpful to their cause as campaigning against the Sony Walkman would have been in the early ‘80s,” Bragg wrote (Fitzgibbon, 2013).

While YouTube isn’t considered a music service, this Google-owned site has become a favorite for fans to check out either official band or audience shot videos. The complex matrix of their partnerships resulting in establishing channels or some sharing of ad revenue (not to mention all of the unauthorized uses of copyrighted music…) make their streaming distributions elusive. Chris Maxcy, Global Director of Musical Partnerships, said YouTube won’t reveal specifics (Caro, 2013).

The bulk of most-viewed videos on YouTube are music, making YouTube the No. 1 music search directory in the world (Chmielewski, 2013). And its executives know that 40% of its viewing already occurs on mobile devices, a fact that most likely prompted their decision to launch a paid-subscription, smartphone-friendly service integrated through Google Play Music All Access in late fall, 2013. Their $10 a month fee allows subscribers to access any songs in their catalog, and create their own radio stations, effectively providing new competition for Spotify (Chmielewski, 2013). The $10 a month fee is the sweet spot for pricing; as it is also Spotify’s monthly fee for endless on-demand streaming (without ads) and $9.99 per month is the new subscription service Beats Music’s charge, as well (Eaton, 2013).

No matter what anyone’s opinion may be on streaming, the technology is here to stay (just like file-sharing and the demand for free or nearly free content). Currently, business models are being created, transformed, and tweaked to suit listeners’ needs, and business models will continue to seek out revenue in new ways. But perhaps what needs a thorough overhaul isn’t these services, but how labels negotiate profit margins on behalf of their artists (Fitzgibbon, 2013).

The Profitability of Services Providing Streaming

Looking at the numbers, royalties paid are a streaming service’s largest expense. In 2012, Spotify’s ‘cost of sales’ including royalties and other unspecified expenses, was $482 million, roughly 83 percent of its total revenue of $578 million. In 2011 this 'cost of sales' took an even larger bite out of revenue at 98 percent! In public statements, company executives state that 70 percent of its income goes to pay licensing fees negotiated with record companies (Sisario, August, 2013).

Spotify, like Pandora, is based on the ‘freemium model’ where free trial subscriptions are used to convert users to paying customers. However, even the free subscriptions (which are in theory supported through advertising), are still expensive to the company because of the fees paid to rights holders every time a track is streamed (Cookson, 2013). At the end of 2012, Spotify announced that of their 55 markets around the world, roughly 25 percent of its users were paid subscribers (5 million of the 20 million users) (Cookson, 2013). In March 2013, the percentage was the same, 6 million paying users out of 24 million total users (Sisario, December, 2013).

And the magic trick is getting users, who have a huge appetite for consuming music for free, to shift to paying a monthly subscription to keep well fed. "There is this irrational resistance for people to actually plunk down their credit card for streaming services," said Ted Cohen, a digital music consultant with the firm TAG Strategic. "We’re 13 years into the Napster phenomenon of ‘music is free’ and it’s hard to get people back into the idea that music is at least worth the value of a cup of Starbucks coffee a week." (Sisario, December, 2013).

Unfortunately, or logically, based on users’ unwillingness to pay for streaming, Spotify has never made a profit (Dredge, 2013). In 2011 the company lost $60 million, in 2012 $78 million (Sisario, August, 2013). And Pandora is in the same boat as their losses have ranged from $14 million to $16.1 million from 2008 to 2012 (Dredge, 2013). While Pandora has 70 million monthly users, only three million of them pay (Sisario, December, 2013).

Pandora is the only streaming company to have gone public (2011) and co-founder Tim Westergren has personally benefitted through selling shares (Dredge, 2013). Pandora is also the most vocal of the services, engaging in arguments between representatives of music publishers, performing rights agencies, songwriters, and artists over the royalties they receive from streams (Dredge, 2013). In June, 2014 the U.S. Justice Department announced it was opening up a 60-day review of antiquated music licensing laws. Whether a revision of the laws can be made to satisfy Internet streaming radio services and representatives of the creators remains to be seen. Most streaming companies make the argument that they are already paying large costs for content and believe middlemen representing artists take too much of the royalty payouts. Pandora’s content costs have increased by 53% over the past five years and, in the first quarter of 2014, increased 25% to $108.3 million (Shalvey, 2014).

On the positive side, Pandora’s ad revenue rose 45% during the first quarter of 2014, to $140.6 million. While investors might be waiting for an increase in paying subscribers, the company could be growing its advertising business so that revenue from free users may prove to be as profitable, or more so, than revenue from paying subscribers (Krause, 2014).

Most services do not provide details on their numbers of subscribers and Spotify’s chief executive, Daniel Ek is quoted as saying, "We’re not a company that will update the numbers with every million subs we get. We will update them when we feel there are important milestones that we reach.” (Sisario, December, 2013). Yet Spotify has chosen 40 million paid subscribers as their target number to achieve mainstream success. The company uses that number to illustrate the revenue it can generate for the music industry once they gain dominance (Sisario, December, 2013). In Sweden, where Spotify was founded and is firmly established, the Swedish recording industry reported that recorded music revenue was up 12 percent in the first half of 2013, as compared to the first half of 2012, and streaming revenue counts for the lion’s share at 70 percent (Caro, 2013).

Numbers of paid subscribers for all streaming services in the United States are not easy to acquire because most services do not report their results. Analysts estimate that the number is a little larger than five million. However, according to RIAA 2013 Statistics, the number of paid subscribers increased from 3.4 million in 2012 to 6.1 million in 2013.

Enter a New Player: Beats Music

In David Byrne’s opinion, “Domination and monopoly is the name of the game in the marketplace,” so how will Beats Music differentiate itself among an already crowded playing field (Byrne, 2013)?

Beats Music was launched on January 21, 2014, by founders rap-star Dr. Dre and record-company-mogul Jimmy Iovine. Dr. Dre was born André Young and was best known as a rapper and music mogul prior to founding Beats Electronics headphone maker with James “Jimmy” Iovine (Faughnder, 2014). Iovine is the Interscope Geffen A&M Chairman and he has served as recording engineer, producer, and music executive for everyone from John Lennon to Lady Gaga (Sisario, 2014). Dre and Iovine insist that the focus of their service is less about access and more about personalized curators who compile online playlists. "It takes a highly curated, uninterrupted sequence of songs to achieve a fulfilling music experience, where the only song as important as the song you are listening to is the song that comes next,” said Iovine (Burrell, 2014). Beats Music was born from the MOG music service Beats Electronic, parent to successful headphone maker Beats (Snider, 2014). The level of success of this curation model will determine how well Beats Music fares against competitors like Spotify, who developed over the last five years their Discover Music recommendation service.

Beats Music enjoys a team of experts at the helm, including Nine Inch Nails veteran Trent Reznor as chief creative officer. He says he wants to add a human element to the service, not just access: "We’re taking the concept of access and adding to it humanity, taste and context. Now I look forward to getting stuck in the car so I can discover music. I haven’t felt that in a long time." (della Cava, 2014). Behind this human element are 30 staff curators who add between three and five new playlists a week, according to Ian Rogers, Beats Music Chief Executive (Pham, 2014). Rogers is no stranger to music and technology. He traveled with the Beastie Boys in the 1990s and handled all of their Internet needs. Then, he headed up Yahoo’s $140 million music service as vice president and general manger in the early to mid-2000s (Pham, 2014). While that service folded, it whet his appetite for the trials and tribulations of subscription music services.

Let’s look at the specifics in getting started with the Beats Music app.

Step one (Figure 5): When you first set up the service on your smartphone or tablet (the service allows you three outlets), you are asked to select your three favorite genres; included in the abundance of choice “bubbles” are Alternative, Hip-Hop, Electronic, Blues. Then, you select three artists that you like or love (one tap for like, two for love) (Snider, 2014). Some could find it limiting to just pick three genres and three artists you love (and you never see those screens again). But you can always add, and love artists later who can become part of your playlists and influence the curators’ recommendations for you. If there is an artist you particularly fancy, you can choose to follow them later on.

Figure 5.

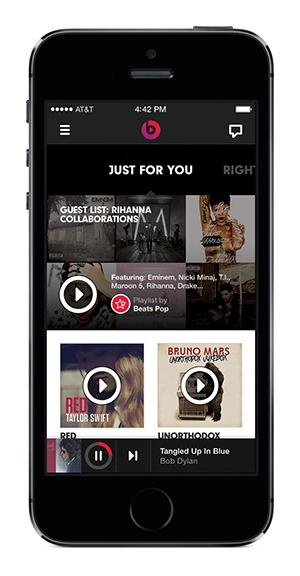

Step two (Figure 5): When you open the app, the ‘Just for You’ screen provides several points of entry – whether you want to listen to a curated playlist designed for you, a specific album or albums by an artist or artists, or a specific song (Snider, 2014). Album cover artwork, links to artist pages, are all visually appealing and the app is fun to play with. Beats by Dr. Dre headphones changed the industry by becoming a fashion statement. This same element of style can be seen with the Beats Music subscription service as well (Snider, 2014).

Figure 6.

When asked about some of the different aspects Beats had going for it, Rogers mentioned the clean aspects of the catalog. He said ‘we treat it as discographies, as artists’ careers and as ways to tell the story of the artist’ (Pham, 2014). They also present the artists’ works chronologically so the listener can see the progression of the music. And it’s designed to be a mobile app, not a Web app transformed (poorly) into mobile platform. All of the albums and playlists on this page are ‘blessed by humans’ said Ian Rogers.

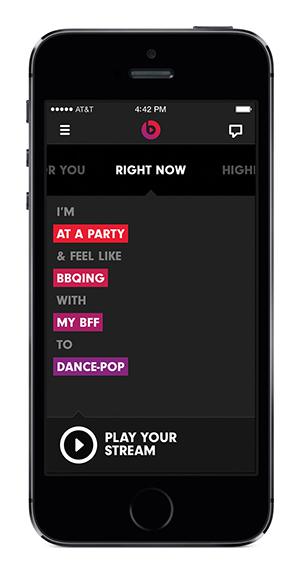

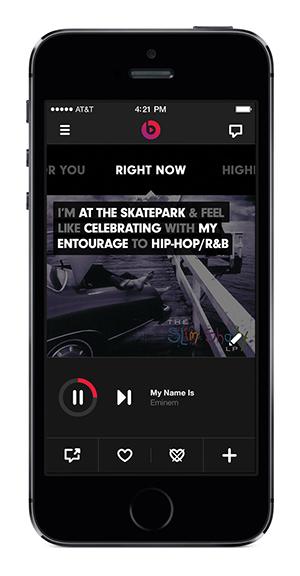

Step three for Right Now (Figure 6): Beats Music wants to get to know the genres you love and wants to give you a playlist perfectly suited to what you are doing right now. Enter the “Right Now” or “Sentence” function for the app to fill that need. This is a sentence with blanks that the user fills in with where they are, what they’re doing, whether they’re with friends and what mood they’re in. The radio algorithm for this function is capable of generating 1.5 million customized lists, tweaked by staff curators (Pham, 2014).

Figure 7.

As music guys themselves, Beats Executives are committed to catering to artists as much as fans. ‘We’re going to offer artists metrics in terms of where their music is being consumed, we’ll allow artists to curate their own pages, and in general provide a friendly place where artists can make fans aware of T-shirts or concert tickets, and consumers can learn more about music and culture,’ said Reznor (della Cava, 2014). This intention is certainly an admirable one. Of course, whether artists will benefit in new ways, receive more royalties, and expand their audiences in ways that translate into monetary gains remains to be seen. In March of 2014, Beats Music purchased Topspin Media, the software company designed to help artists sell and promote their music directly to consumers, and Beats itself was purchased by Apple in May (Faughnder, 2014). There is certainly a momentum building and which way it swings for artists will be more apparent in the months ahead.

To head up the Curation department, Beats Music snagged 20-year radio veteran from Clear Channel stations, Julie Pilat. In her words ‘to change the path of the future of music is the opportunity of a lifetime…I couldn’t say no’ (Halperin, 2013). In her opinion, there is a lack of options for listeners. ‘If you know what you want to listen to, you pull it up; but if you don’t, you get stuck. Curation will find that community with a true passion for music. That’s what’s going to set us apart’ (Halperin, 2013). In that spirit, the service is meant to be a curated recommendation service first, playlist creator second. For instance, Beats hired Scott Plagenhoef, former editor of the music site Pitchfork, Carl Chery, former digital content director at XXL, Recording Academy music blogger Arjan Writes, and formed partnerships with Target, Rolling Stone magazine, the fitness chain SoulCycle, Thrasher skateboarding magazine and the Academy of Country Music to come up with lists better than listeners could do on their own (Pham, 2014; Wood, 2014).

This crew of curators comes up with a Highlights page of Expert Essentials that has images of albums, artists and playlists they’ve handpicked. And on the Find It page users can search an abundance of playlists according to a specific genre, (Christian, Classic Rock, Experimental) activity, (Being Blue, Cooking, Partying Poolside) or specific curator, (Dancing Astronaut, Latina Magazine, The Ellen Show).

According to Rogers, services like Pandora and Spotify rely too heavily on computer algorithms and the people behind the data don’t understand music. Pandora uses automated musicological analysis for song selection and Spotify analyzes huge data pools. Beats admits to using algorithms as well, but the difference they say, is they make more use of human curators (Sisario, January, 2014).

The Artist page (Figure 7) provides information on whoever is searched or clicked on from another page. As mentioned before, the layout is clean and visually appealing. Listeners can indicate whether they like a song or not (via heart icon), they can provide comments and they can post the track and/or playlist on Facebook or Twitter and they can follow an artist (Pham, 2014). Currently, Beats doesn’t have complete integration between fan and artist to allow fans to learn tour dates, buy tickets and merchandise, but has plans to do so. Rival Rhapsody already has this feature (Pham, 2014).

Personally, I’ve signed up for Beats Music and have the service on my smartphone, work computer and home laptop (the service allows three interfaces). I encountered some kinks with the website’s usability on my laptop, however I don’t experience the delays or sudden stops on my iPhone 5. The app does appear to be most suitable for phone use. I pay $9.99 a month, tuning in for free to Beats Music is not an option after a 7-day trial period. (This 7-day trial period was extended to 14 days after purchased by Apple in late May, 2014 (Byford, 2014).) Unlike other streaming services, there is no free option. Their business model does not have a free option! The trial period for the service packaged with AT&T family plans is longer, for a full three-months, before switching to the paid service fee (Byford, 2014). Could they be on to something? Paid subscriptions generally translate into higher royalty rates. No specific numbers have been provided by the company at this point, they have just said they pay all labels equally (Sisario, January, 2014).

After 100 days of business, the Beats subscriber count was estimated by label sources to be in the ‘low six figures’ (Adegoke, April, 2014). The most important number the labels look at is known as the conversion rate, or the rate at which free trials on streaming services lead to full fledged paying customers. Beats declined to provide specific numbers, but company insiders simply state their subscriptions and consumer responses have met their expectations (Adegoke, April, 2014).

Beats Music Promotion, Funding and Purchase by Apple

In addition to cool, creative type executives, Beats Music is backed by a wildly successful headphone brand. In fact, exploiting that brand through aggressive marketing is part of their two-part strategy. The other part of their strategy is to serve its listeners by de-cluttering their listening environment, entertaining them with bold visuals and choices, and offering the human touch of music recommendation (Sisario, January, 2014).

The company also had $60 million in investment prior to launch from Access Industries, the investment company founded by billionaire Warner Music Group owner Len Blavatnik. As of March, 2014, Beats announced another influx of cash to the tune of $60 - $100 million from Access again, as well as some other backers (Faughnder, 2014).

Their aggressive marketing campaign included an integration deal with AT&T (who offers a family plan for $15 for up to five users), regular plugs on “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” and a Super Bowl ad. AT&T, Target and Ms. DeGeneres will be promoting Beats Music heavily. A new focus on families and adult women are two demographics that have been off the radar for digital music marketers in the past (Sisario, January, 2014). The bundling of Beats service with AT&T users prompted Spotify to announce a similar arrangement they negotiated with Sprint in late April, 2014. The competition for subscribers is intense and label executives believe that it is easier to bundle streaming subscription services at a discount through the mobile carriers’ bills, than it is for customers to sign up through the streaming sites (Adegoke, April, 2014).

Currently Beats is just available in the U.S., but with internationally-reaching Spotify as a rival, and the extra access to worldwide users acquired through its recent purchase by Apple, expansion into other markets seems likely. When asked about potential market numbers, Rogers puts it at 50 million in the U.S., or ten times what it is currently. As a comparison - Netflix has 31 million subscribers and Sirius XM Radio has more than 25 million – indicating that large scale companies that are charging for access are profitable (Sisario, January, 2014).

While there is a consensus that the shift to streaming will happen, the speed of the profitability of streaming to companies is still uncertain (Dredge, 2014). And there is the possibility that if streaming doesn’t grow legs on its own, the service will only be offered if subsidized by other parts of the providers’ business. There are already several high margin tech companies (Apple, Google, Amazon, Samsung, Sony, Microsoft) who have already offered, or have plans to offer streaming services. No one can deny Apple’s success in using low-margin music sales to rev up demand for iPods, phones and computers (Sisario, December, 2013). Incidentally, Headphones-maker Beats is believed to have earned $1.4 billion in revenue during 2013 (Dredge, 2014).

In keeping with that mindset, Apple purchased Beats Electronic, including Beats Music, for $3 billion in late May, 2014 (Mangalindan, 2014). While the deal won’t close until the end of the year, this purchase changes the landscape of the streaming industry because it may encourage likeminded tech giants like Google or Amazon to buy one of Beats’ competitors. At the time of the purchase, Beats had less than 200,000 subscribers and was valued at a little more than $300 million. Meaning that 90 percent of the company’s value lies within the headphone and speaker brand. Even though Beats is a young subscription service, label executives believe the service plays into Apple’s business strategy (Adegoke, May, 2014). ‘To a certain extent they’re buying some brand equity, some positioning in the market with the younger generation, with the hip-hop generation,’ said Van Baker, a Gartner research analyst (Mangalindan, 2014).

Under the umbrella of Apple, Beats is trying to increase the number of subscribers by extending the free trial from 7 to 14 days (mentioned earlier) and reducing the yearly rate from $119.88 to $99.99 (Byford, 2014).

Beats has reason for optimism – while free discovery is possible on Spotify and Pandora, Beats signifies a new set of values, catalog depth, and expert advice. Listeners may want to discover music at their convenience and with a touch of a button, yet crave the attention of being at a record store that’s filled to the brim with musical possibilities and willing aficionados to guide them (Snider, 2014). Beats could be just what they are looking for and now with the backing of Apple they may be poised to reach out to potential and existing subscribers in new and interesting ways.

Conclusion

From the research performed for this paper, it is clear that music streaming is a service demanded by listeners and it represents a growing portion of the total music industry revenues. The conversion rate from the “free” to the “paying” model is currently in a state of infancy and flux. Recording artists are receiving minimal income from streaming revenue as compared to record labels. This is due in part to payouts generally being small to begin with and recording contracts using antiquated percentages that do not reflect this new revenue stream. Labels are making money through advances to have access to their catalogs and high license fees. The well-known companies like Pandora and Spotify are not profitable due to high license fees paid to copyright owners of music and an inordinately large percentage of listeners tuning in for free. However, there are clearly attempts being made by streaming services to generate enough ad revenue to make up for non-paying users. This model may work for giants like Pandora and Spotify. Or not.

The recent purchase of Beats by Apple, the bundling of streaming services with mobile services and the continued efforts of streaming services generating ad revenue are all trends that will continue to affect the streaming industry.

Beats Music is a recent streaming service that is differentiating itself through a creative team of music industry veterans who are dedicated to curating playlists for listeners and designing a clean, visually appealing music platform, both influenced heavily, and regularly by humans. The cool culture of Beats Music attracted Apple to purchase it. Beats had enormous startup funding, an established brand name in Beats Headphones, an aggressive marketing campaign and strategic partnerships with organizations and individuals to strengthen their services. With the “free” model not an option for Beats, it will be interesting to see their numbers of subscribers in the months ahead. Jimmy Iovine and Trent Reznor are confident that Beats will succeed.

‘If a service is great enough, it can be more rewarding than owning (music). I want to be part of the solution for the artist and the business’ said Iovine (della Cava, 2014).

‘What is the next business model? Somebody’s got to crack it. Why not me?’ Reznor (Sisario, 2014)

References

Adegoke, Yinka. “The Future of Streaming.” Billboard, May 24, 2014, Vol. 126 Issue 17.

Adegoke, Yinka, Alex Pham and Ed Christman. “Beats: The First 100 Days.” Billboard, April 26, 2014, Vol. 126 Issue 13.

Burrell, Ian. “Why Spotify can’t forget about Dr. Dre’s new venture; This Digital Life; The Humble DJ has been renamed and rebranded.” Belfast Telegraph, January 25, 2014.

Byrne, David. “Road to Nowhere: Pandora, Spotify – digital streaming means profits for record labels and free content for users, but what does it mean for artists? David Byrne fears the internet is sucking up the creative content of his industry.” The Guardian, October 12, 2013.

Byford, Sam. “Beats Music lowers its pricing as Apple buys it out.” The Verge, May 28, 2014. Accessed June 23, 2014. http://www.theverge.com/2014/5/28/5759534/beats-music-lowers-its-pricing-after-apple-acquisition.

Caro, Mark. “Revenue stream; despite surge of online music services, artists say their cut is a drop in the bucket.” The Baltimore Sun, October 6, 2013.

Chmielewski, Dawn C. “Company Town; You Tube capitalizes on music; The video giant’s subscription service aims for the important mobile market.” Los Angeles Times, October 25, 2013.

Cookson, Robert. “ Spotify costs soar in drive for paying subscribers; Software.” Financial Times, August 1, 2013.

Della Cava, Marco R. “Iovine and Reznor demand a service that’s ‘personal’; Beats Music will not be an ‘impenetrable wall’ for listeners.” USA Today, January 13, 2014.

Dredge, Stuart. “Spotify, Pandora and the profits problem for streaming music.” The Guardian, August 1, 2013.

Eaton, Kit. “Streaming for a Good Beat That’s Just to Your Taste.” The New York Times, August 29, 2013.

Faughnder, Ryan. “Beats Music raises more funding to take on streaming rivals.” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2014.

Fitzgibbon, Rebecca. “It’s too late to close Pandora’s Box of music sharing.” Hobart Mercury, November 13, 2013.

Halperin, Shirley. “Jimmy Iovine Plucks Radio Vet Julie Pilat to Head Up Curation for Beats Music.” Hollywood Reporter, August 7, 2013. Accessed January 31, 2014. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/julie-pilat-curate-beats-music-600249.

Krause, Reinhardt. “Pandora Stock Falls, Q1 Active Listeners Down Vs. Q4.” Investors Business Daily, April 25, 2014.

Lindvall, Helienne. “Will Beats Music trump Spotify with its artist charm offensive?” The Guardian, January 15, 2014.

Mangalindan, JP. “Apple’s $3 billion Beats purchase: What they’re saying.” Fortune.com, May 29, 2014. Accessed June 14, 2014. http://fortune.com/2014/05/29/apples-3-billion-beats-purchase-what-theyre-saying/.

Pham, Alex. “Beats Music: A Step-By-Step Walk Through.” BillboardBiz, January 11, 2014. http://www.billboard.com/biz/articles/news/digital-and-mobile/5869545/beats-music-a-step-by-step-walk-through.

Recording Industry Association of America. http://www.riaa.com/keystatistics.php?content_selector=2008-2009-U.S-Shipment-Numbers (Accessed January 21, 2014, April 15. 2014).

Salvey, Kevin. “Music Royalties in Web Age Creating Lack of Harmony.” Investors Business Daily, June 11, 2014.

Sisario, Ben. “Algorithm for Your Personal Rhythm.” The New York Times, January 11, 2014.

Sisario, Ben. “As Downloads Dip, Music Executives Cast a Wary Eye on Streaming Services.” The New York Times, October 21, 2013.

Sisario, Ben. “A Stream of Music, Not Revenue.” The New York Times, December 13, 2013.

Sisario, Ben. “Spotify Losses Grow, Despite Successful Expansion.” The New York Times, August 1, 2013.

Snider, Mike. “Beats Music jazzes up song discoveries; Service clues you in to music you may like.” USA Today, January 21, 2104.

Sound Exchange. http://www.soundexchange.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/2012-Annual-Report-06-13-13.pdf (Accessed January 21, 2014).

Wood, Molly. “Beats Hopes to Serve Up Music in a Novel Way.” The New York Times, March 13, 2014.