Cultural Influences on Organ Music Written By African American Women 1

Abstract

In this paper, major events in African American history are described and contrasted with the history of organ music written by African American women in the twentieth- and the twenty-first centuries. The discussion includes the emergence of women's rights, especially women composers. The author traces the beginnings of African American women composers from church music to all other forms of musical performance. Included in the paper are the history, works, and styles of Florence Price (1887-1953), Undine Smith Moore (1905-1989), Zenobia Powell Perry (1908-2004), Betty Jackson King (1928-1994), Shirley Scott (1934-2002), Judith Marie Baity (b. 1944), Sharon J. Willis (b. 1949), Eurydice V. Osterman (b. 1950), and Regina Harris Baiocchi (b. 1956). As this discourse reveals the struggles and history of women composers in general, it also gives hope to the future of exploration in this field. With easier exposure to this music and continued advancements in culture and technology, research will continue into black music history, and especially into the music of African American women.

One misconception about African American classical music works is that they are only based on Negro Spiritual themes and folk songs.2 While it is true that many of them are from this source, other works of African American composers are a reflection of social changes in black history. In addition, African American composers were not only influenced by their culture. They were also affected by the changing styles and periods represented in music history as a whole. These musicians and their music were shaped by the African American experience. The struggle for justice, equality, integration, and acceptance in the large mainstream culture have led to the renewal of pride in African heritage and its incorporation into the European American milieu of art, literature, and music.

“The works of African-Americans, particularly those writing for the organ, are based upon a rich and diverse set of influences that include not only spirituals but plainchant, general Protestant hymnody, German chorale tunes, themes of African origin, and original themes.”3 African American elements can also be heard in works by composers of European descent. “Dvorak, Ravel, Gershwin and Bernstein are noted for their inclusion of elements that are considered African-American.”4 There is not one absolute definition of “black music” that pertains to every piece written by an African American composer. As stated by Mickey Thomas Terry:

As with most other ethnic groups, African-Americans are heterogeneous by nature and, therefore, cannot always be said to approach all issues from the same point of view. As this is the case, one encounters not only the diversity of compositional styles but philosophical differences as well. One issue about which there has been a long-standing difference of opinion among black composers pertains to what constitutes ‘black music.’ 5

The Harlem Renaissance was an important movement both in the definition and the celebration of black music. The migration of African Americans in the early 1920s brought them to northern cities such as New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. In the Harlem section of New York City, African American literature, art, music, dance, and social commentary began to flourish. African Americans were encouraged to celebrate their heritage. This came at a time when a nationalistic revival of folk music was flourishing in many areas of early twentieth-century music in Europe and America. “But it was in the realm of concert music that Renaissance thinkers hoped for great achievement, expecting that black folk music would serve as the basis for great symphonic compositions that would be performed by accomplished black musicians.”6 “Eileen Southern has ... identified as black nationalist composers such figures as Harry T. Burleigh, Clarence Cameron White, Robert Nathaniel Dett, Harry Lawrence Freeman, Florence Price, J. Harold Brown, and William Levi Dawson, writing that they all ‘consciously turned to the folk music of their people as a source of inspiration for their compositions.’”7 “In critical discussions of the first orchestral music by black American composers, William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony, Florence Price’s Symphony in E minor, and William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony are often cited in the context of American musical nationalism.”8 Although The Harlem Renaissance ended in the 1930s, African Americans continued to compose in a variety of genres.

As Eileen Southern has written: “Though rarely discussed in the literature, black women composers of church music have played an important role in the development of the genre ever since the first independent black churches in the United States were founded in the 1790s.”9 The first known black woman church organist was Ann Appo (1809-28), who was given the position when St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Philadelphia purchased an organ in 1828. Notably, The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ) published their own hymnals. Generally, in other denominations, the hymnals of the affiliated white churches were used.

The following is a chronological list of African American women composers for the organ compiled in research for this article: Florence Price (1888-1953); Loretta Manggrum (1896-1992); Undine Smith Moore (1905-1989); Zenobia Powell Perry (1908-2004); Evelyn Pittman (1910-1992); Julia Perry (1924-1979); Ruth Norman (b. 1927); Betty Jackson King (1928-1994); Shirley Scott (1934-2002); Charlene Moore Cooper (b. 1938); Judith Baity (b. 1944); Dr. Sharon J. Willis, (b. Cleveland, 1949); Eurydice V. Osterman, (b. Atlanta, 1950); Evelyn Simpson-Curenton, (b. Philadelphia, 1953); and Regina Harris Baiocchi, (b. Chicago, 1956). These composers were found in journals, books, music, and music periodicals at the beginning of the 21st century. There are undoubtedly more African American women composers, but these were the ones named and written about in the sources referenced. Without making this article overtly lengthy, nine of these composers and their works are highlighted in this discussion.

It was not until the last decade of the 19th century that women composers emerged into the classical music scene in America as well as in Europe. Therefore, black women composers were also late to be recognized. “It was not until the white composer Mrs. H.H.A. Beach (1867-1944) wrote her Mass in E-flat Major, Gaelic Symphony, and Piano Concerto in C-Sharp Minor during the last decade of the 19th century that American women composers began to claim their place alongside their male colleagues. Performances of Beach’s music would have been heard by the black composer Florence Price while she studied in Boston, and may have inspired her own ambitions.”10

Florence Price (1887-1953)

Scholars disagree on whether Florence Price was born on April 9, 1887 or April 9, 1888. But all agree that she was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, and died in Chicago on June 3, 1953. She began her piano study at age four in a public recital. She “received further musical training from her public school teacher, Charlotte Andrews Stephens, who also taught William Grant Still.”11 Her father James was a dentist in Little Rock and also a successful inventor and painter. Her mother Florence was a talented soprano and concert pianist.12 Since her parents were both artistic, they both guided her early musical training, and at age fourteen, she enrolled in the New England Conservatory of Music with a major in piano and organ. She studied with George Chadwick and Frederick Converse. After she graduated from college, Price returned to Little Rock and taught at Shorter College in North Little Rock, Arkansas (1906-1910), and then at Clark University in Atlanta, Georgia (1910-1912). Price was also an active church organist at this time in her life. “Humble in demeanor and deeply religious, Price often used the music of the black church and made a number of arrangements of spirituals.”13

In 1927, Price moved to Chicago because of increasing racial tensions in the South.14 In Chicago, she studied at the Chicago Musical College, the American Conservatory of Music with Leo Sowerby, and Chicago Teachers College. At this time, Price “began to win awards for her compositions (1926 and 1927 Opportunity magazine prizes). In addition, [she] wrote musical commercials for radio.”15 “She was also an accomplished theater organist, accompanying silent films in movie theaters in Chicago.”16 Many of her pieces were played by organists, especially members of the Chicago Club of Women Organists. Janet Nichols has stated that: “Perhaps her favorite organization was the Chicago Club of Women Organists.”17 Her works were performed by herself and others in recitals for this organization.

On June 15, 1933, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (conducted by Frederick Stock), performed her Symphony No. 1 in E Minor at the Chicago World’s Fair (“A Century of Progress Exhibition”)18. This was “the first time in history that a major orchestra had performed the symphony of a black woman.”19 “Price was the first African-American woman to win widespread recognition as a symphonic composer, rising to prominence in the 1930s.”20 Her orchestral works were later performed by other leading orchestras, including the American Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Chicago Women’s Symphony, Chicago Chamber Orchestra, Brooklyn (NY) Symphony and Pittsburgh Symphony. Symphony No. 1 in E minor and two other compositions by Price were entered in the 1932 Rodman Wanamaker Music Contest. “All were prize-winners, with the symphony taking first place.”21 At this time, Symphony No. 1 in E minor brought Price national recognition.

While in Chicago, Price formed a “friend-teacher relationship with Estella Bonds and her daughter, Margaret.”22 Margaret Bonds (1913-1972) studied with Florence Price, and performed many of Price’s works. Bonds also won a third prize in the Rodman Wanamaker Awards of 1932.

Two of Florence Price’s contemporaries were William Grant Still and William Dawson. Their early music “may be placed within the context of nationalism in American music. African American folk music, both sacred and secular, provided the musical foundation for these composers. Price’s music may also be placed in the context of the Harlem Renaissance ... movement of the 1920s and 1930s.”23

The short organ works of Florence Price are compiled in Music of Florence Beatrice Price, Vol. 2, edited by Calvert Johnson, 1995. These works are “intended for the average amateur church organist. ... [They] make only slight demands on the performer and are very accessible to an audience.”24 They are generally “ternary structures with lyric melodies and pleasant harmonies.”25 Many of Price’s organ pieces recall Negro Spirituals and folk tunes. The Hour Glass and Retrospection have melodies which are basically pentatonic like most folk-songs and Spirituals of African Americans (see Figure 1).”26 The influence of jazz can also be felt in these short works. Volume 2 includes detailed information on Price’s short organ works including registration, stop lists of organs played by Price, and recordings of these works. All of Price's music composition can be attributed to a combination of her music education and life as an African American woman. Even though these short works were written for a specific purpose, they incorporated all of her musical skills. They were short reflections of larger forms of her music, not just average church pieces.

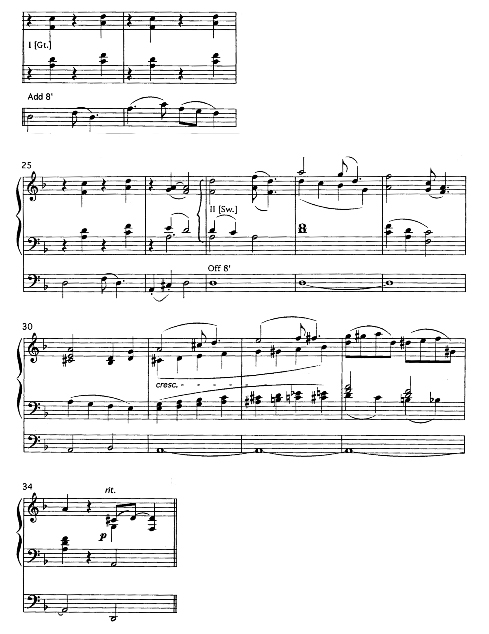

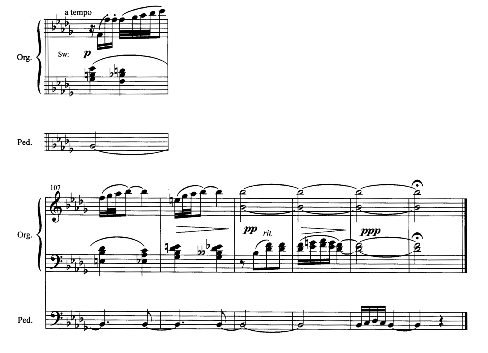

Figure 1. The Hour Glass by Florence Price, mm. 23-34.

As noted by Mildred Denby Green, “[Price] spoke the language of the black musical idiom with authority and blended it with the logic of traditional European music.”27 “Within traditional forms (especially sonata allegro, concerto, song forms and fugue), she frequently used spirituals, or themes similar to those of Spirituals, Juba dance, and jazz harmonies and rhythms.”28 “Although Florence Price composed many settings of Spirituals for voice and piano, ... Variations on a Folksong was the only organ composition which she composed as an organ arrangement of a Spiritual besides Steal Away to Jesus.”29

Variations on a Folksong is a work based on the folksong Peter, Go Ring Dem Bells. The piece starts out simply, with a calm, plain statement of the tune (see Figure 2). There are then fifteen variations that build in intensity and include canon style (see Figure 3), many jazz idioms, chromaticism, toccata passages (see Figure 4)—all basic characteristics of the late Romantic style. This work of course sounds the best on a large, Romantic organ to which Price would have had access. The dramatic, thunderous conclusion of the piece is even more intensified if one has an organ equipped with chimes, since the indication on the music suggests that the chimes ring out over a pedal trill until the final full-organ chord of the piece. This work can be shortened and/or rearranged easily, since the variations can be linked together in a number of imaginative ways.

Figure 2. Variations on a Folk Song by Florence Price, main folk tune.

Figure 3. Variations on a Folk Song by Florence Price, Variation VIII, canon style.

Figure 4. Variations on a Folk Song by Florence Price, Variation XIII, toccata style.

Calvert Johnson states, “perhaps the first national attention received by Florence Price as an organ composer occurred during the National Convention of the American Guild of Organists in Atlanta in 1992. Shayne Doty performed the Suite No. 1 for Organ at Decatur First Baptist Church, on a July 1, 1992, program of works by African and African-American composers.”30 Johnson gave international exposure to Suite No. 1 in a series of European recitals in 1993.31

The main themes of the inner movements of Suite No. 1 for Organ recall Spiritual melodies without quoting them exactly (Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child as the subject of the Fughetta, and Let Us Break Bread Together [found] in the Air).32 The following is a description of the work:

[It] opens with an improvisatory Fantasy, where scale flourishes punctuate dense harmonic passages. The Fughetta shows Price's contrapuntal skill in setting a coy subject in compound meter over weaving chromatic lines. Chromaticism is also exploited in the following Air, a movement of wistful nostalgia that is reminiscent of Vierne. The Suite closes with a Toccato (sic) on a traditional American melody.33

Although Price's music is sophisticated musically, it is always a combination of her knowledge of music principles at the time and her African American roots.

Florence Price’s “style was [late] Romantic, and consisted of some technically difficult devices as well as smaller designs intended for intermediate levels.”34 She “fused the various elements of her background—African, American, European and female—into her organ music.”35 “She wrote in all genres except opera, producing works for piano, organ, voice, chamber ensembles, orchestra, and chorus and arranging spirituals for voice.”36 Jazz harmonies and rhythms were also incorporated into many of her works.

Archives of the music written by Florence Price are held at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Please see Appendix for more information on the organ works of Florence Price and publication information.

Undine Smith Moore (1905-1989)

Born in Jarratt, Virginia, and the granddaughter of slaves, “Undine Smith Moore graduated from Fisk University (1926) with highest honors and received a M.M. degree at Columbia University. She pursued additional study at the Juilliard School. She was the first student to earn a Fisk Scholarship to study music at Juilliard, the Eastman School, and the Manhattan School of Music. From 1927-1972, she served on the music faculty of Virginia State University in Petersburg. She received honorary doctorates from Virginia State University (1972) as well as Indiana University (1976) in Bloomington. Although she wrote for organ, piano, voice, flute, and chamber ensemble, Moore is primarily known for her choral compositions.”37

“Moore began publishing relatively late in her career and belongs to that group of Black composers who had long teaching careers at Black colleges in the South. She taught music for forty-five years at Virginia State College, Petersburg, Virginia, where her students included such outstanding musicians as Billy Taylor, Leon Thomspon, Louise Toppin, and Camilla Williams.” 38 Billy Taylor is one of America’s premier jazz pianists and has won Grammys, two Peabody Awards, an Emmy, International Critics Award, and a Jazz Masters Fellowship of the National Endowment for the Arts. In an interview, he talked about the importance of music and music education and his dedication to Music Education.39 When Taylor was asked about his early teachers—Henry Grant and Undine Moore—he stated:

If a teacher can be judged by her students, Undine Moore did fine, certainly in terms of the breadth of her impact. One of her former students, Camilla Williams, became an opera singer, and another, Phil Medley, wrote at least one song for the Beatles. But the thing that I most remember had to do with the fact that, in those days, we were required to go to the college chapel every Sunday. Well, she was the chapel pianist and, since she had a captive audience, she used the occasion to compel us to listen to composers and music that we would never have listened to on our own. It was sneaky, but it worked. ... “She was the true role model, both as a musician and a teacher. ... Whenever any of us—her former students, I mean—run into each other in various places around the country, her legacy is always a part of our reunions. ... As a teacher, she broadened all of us. She had a deep insight into the Impressionists, for example, but she also knew and loved Bach and was especially eager to unfold all the intricacies of his music.”40

Moore was an inspiration to many students and thought of herself as an educator, not only a composer. She familiarized students of all ages with her innovative ideas.

Composers teaching at black colleges in the South tended to write music using black folk idioms, and, frequently, made arrangements of spirituals and other folksong types. The composers could be sure that their works would be performed by the college groups where they taught, not only on the campus but also when the groups went on tours. In this way, the music became known away from the campus where it originated, even though much of it might not have been published. When the music was published, of course, it reached a larger audience.41

Many of these composers had long tenures at the institutions where they taught, beginning there early in their careers and remaining until retirement.42

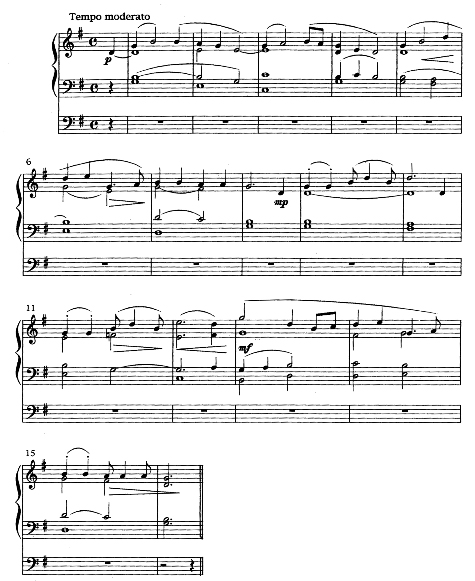

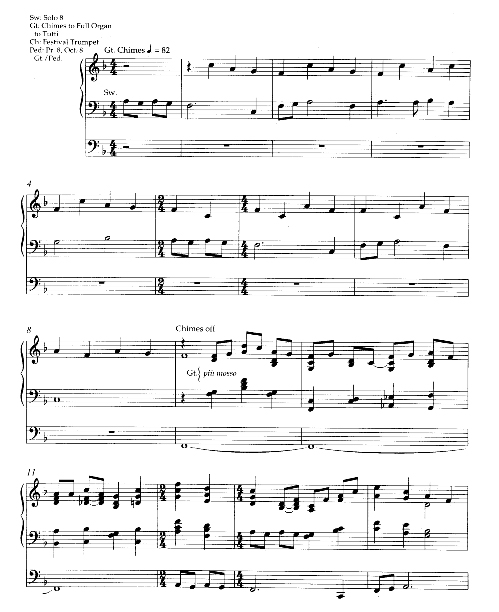

Moore wrote only two solo works for organ, and they are both based on hymn tunes. Organ Variations on There is a Fountain, 1979 has been lost.43 Variations on Nettleton (“Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing”), commissioned in 1976, offers our only example of Moore's work for this particular instrumentation. It is a short piece (2-3 minutes) in the key of C major. It “begins with a variation based on the tune. The melodic line in the first variation is in the soprano voice and is accompanied by triplets in the left hand (see Figure 5). A brief interlude follows, and the second and last variations present the melody in the pedal voice.”44 The brief interlude consists of chromaticism on the manuals followed by a forte pedal entrance, which gradually diminishes to a piano with large leaps in the manuals and pedals. The last four measures—Allargando e maestoso—are chromatic and the piece ends with four distinct chromatic jazz chords (see Figure 6).

Figure 5. Variations on Nettleton (“Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing”) by Undine Smith Moore, opening measures.

Figure 6. Variations on Nettleton (“Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing”) by Undine Smith Moore, last five measures.

Undine Smith Moore was among the composers who published fairly regularly during the 1940s-60s.

Black composers coming to musical maturity during the 1940s-50s found that the curtain of racial discrimination was beginning to lift ever so slightly. Fellowships became more accessible, opportunities for performance came more frequently, and music critics and publishers less often insisted that ‘black music’ had to be jazzy or folksy in order to be acceptable. Then too, the composers themselves were becoming more independent, having gained a measure of economic stability by securing positions as music editors and/or university professors. Freed of the necessity to write ‘race music’ in order to secure performances, they began to reach out to larger audiences, writing music that carried no identifiable clues as to the origins of its composers. ... Moore also lectured widely on black music and was co-founder/co-director with Altona Trent Johns of the Black Music Center at Virginia State, which brought the leading black artists and composers of the nation to the campus during the years 1969-72.45

Black composers at this time were beginning to realize that their music did not have to include previously-accepted forms of black music, and therefore branched out into mainstream musical concepts.

In a quote from The Black Composer Speaks, Moore states, “I will say, if forced, that I use the term black music to describe music created ‘mainly’ by people who call themselves black, and whose compositions in their large or complete body show a frequent, if not pre-ponderant, use of significant elements derived from the Afro-American heritage.”46 As with the other composers of this era (1940s to 1960s), Moore also incorporates standard, classical musical style within her works. “Of homophonic and polyphonic textures, her structures are well formed and full of emotional sensitivity and change.”47

A checklist of scores of Moore’s works can be found in the Helen Walker-Hill Collection at the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR), Columbia College, Chicago, and also at the American Music Research Center (AMRC), University of Colorado at Boulder. A complete list of compositions by Moore has also been compiled by her daughter, Mary Easter, from her personal collection (1990 Unpublished).48 See Appendix for more information.

Zenobia Powell Perry (190849-2004)

Zenobia Powell Perry was a Black Creek Indian woman born in Boley, Oklahoma. She died on January 17, 2004 in Xenia, Ohio. Jeannie Gayle Pool states: “It is the highest tribute to Perry that she managed to develop the career and write the music she has in this country, as a black native American woman born in 1908.”50 Perry studied with William Dawson at Tuskegee Institute (Bachelor of Music Education degree) and with Darius Milhaud at Wyoming University and at Aspen. She also received the Master of Music Education degree at Northern Colorado State at Greeley and taught at AM & N College (now Arkansas State) and Central State University in Ohio.

Perry decided to seek additional training in theory and composition when she was forty-one years old. She attended the University of Wyoming after hearing that there were some excellent theory teachers there, particularly a counterpoint teacher. She auditioned in the spring of 1949 and was introduced to the French composer Darius Milhaud (1892-1974). He invited her to study composition with him. Perry is quoted as saying: “You could have bought me for a penny that day because Milhaud was interested in me taking composition classes with him.”51 She also studied with Allan Arthur Willman (1909-1989) at the University of Wyoming.52

Milhaud was also interested in black music.53 “His own ballet, La Création du monde (1923), which portrays the Creation in terms of ‘Negro cosmology,’ is often cited as the earliest example of the use of blues and jazz in a symphonic score.”54 “As a part of her assistantship at the University of Wyoming, Zenobia Perry took some musical dictation from Milhaud, when his arthritis was too bad, and generally acted as his personal assistant while on campus.”55 Perry has stated that Milhaud was an encouraging teacher, always complimentary, kind and compassionate.56 Through her studies with Milhaud, Willman and Charles Jones (a Canadian-born American composer and teacher, b. 1910), Perry “discovered many composers, particularly European, but also American, whose works she had never heard. They introduced her to the style of international contemporary music, which dominated the new music scene in America and Europe in the late 1940s and 1950s.”57

Perry began teaching at Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio in 1955, where she taught composition and theory and was a resident composer at the University. Having taught there for almost thirty years before retiring, “Perry was saluted for cultural contributions by the Ohioana Library Association in 1987, and in 1988 she was honored by the Hall of Musical Instruments at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History. The Ohio General Assembly presented her with a ‘Lifetime Achievement Award’ in 1991.”58

Perry’s three works for organ include: Festival Overture (c. 1954), Prelude (1973) and Prism for Organ (1975). Her organ works were performed by organists Mike Moss at Southern Connecticut State University and William Haller at West Virginia University.”59 Information concerning details about Festival Overture can be found at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Prelude is a modal, meditative, free-form piece. The piece is mostly soft with a crescendo section which leads to an F sharp major chord. A three-measure adagio ends the piece in F sharp major. Prism is also based on modal harmony. This work incorporates the use of strings, flutes and a soft reed for organ registration. The piece ends with a crescendo to a final G major chord.

Perry wrote works in many genres—art songs, choral works, an opera, works for concert band and symphony orchestra, chamber music, and works for solo piano and organ. As was the case with many black composers of her generation working at black colleges and universities, Perry also produced many arrangements of spirituals at the request of colleagues and students. The general characteristics of her style are described by Jeannie Gayle Pool:

Most of her writing is straightforward and conventional. Some pieces reveal a fondness for the rich harmonic language of ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords. ... Her melodic lines are often modal or pentatonic and she sometimes uses a flat third (or flat ninth) in the melody or in the chord accompanying the melodic line, against a major third in the bass. She also uses half-diminished seventh and ninth chords. ... Many of her dissonances do not resolve. ... In some pieces she works with tritones and quartal harmony. She often uses parallel voicing that increases the sensation of modal, rather than tonal, harmony. ... Every note in her writing seems carefully thought out and placed.60

As with other composers discussed in this paper, Perry wrote for many different genres of music, not only for organ.

The first recording devoted to the works of Zenobia Perry, “Music of Zenobia Powell Perry, Volume I: Art Songs and Piano” was released in 2002 by Jaygayle Music and Cambria Master Recordings of Lomita, California. The performers are Janis-Rozena Peri, Soprano, John Crotty, piano and Joyce Catalfano, flute. All are members of the music faculty at West Virginia University. Peri is the daughter of Zenobia Powell Perry. See Appendix for scores and music manuscript collections.

Betty Jackson King (1928-1994)

Over my head, I hear music in the air.

Over my head, I hear singing in the air.

There must be a God somewhere.

This statement was Betty Jackson King’s creed, according to her website.61 “Music was her life. She lived it, expressed it, expanded it and above all shared it.”62 King was influenced all her life by the spirituals she heard in Vicksburg, Mississippi, at the Southern Christian Institute where her mother (Gertrude Jackson Taylor) taught music. She received the B.M. in piano (1950) and the M.M. in composition (1952) from Roosevelt University, Chicago, Illinois. She taught in the Chicago Public Schools and at the University of Chicago Laboratory School, Roosevelt University, Dillard University (New Orleans, Louisiana), and Wildwood High School (Wildwood, New Jersey). King was a composer, choral director and clinician, educator, keyboard artist, lecturer, church musician, and publisher. From 1979 to 1984, King was President of the National Association of Negro Musicians.

King’s only known work for organ is Nuptial Suite which consists of three parts: (1) Processional, (2) Nuptial Song, and (3) Recessional. Registration suggestions by Oland P. Gaston, editor, appear on the page before the music begins. Processional opens with a seven-measure introduction with the tempo marking “Grandioso.” The registration calls for a full organ sound. The manuals are both written in the treble clef and would have to be played on separate manuals or one hand would have to play the notes an octave higher or lower than the other. There is no indication of how this is to be played on the music itself. This is a chromatic and dissonant piece of extreme technical difficulty. For example, in this opening introduction, there are many passages for simultaneous octave reaches between the manuals and pedals.

The next section of the Processional is the “Cantabile” which is also chromatic and dissonant, but calls for a softer registration for flutes and strings, including a flute céleste and a voix celéste. It begins with an ostinato accompaniment under a melody in thirds, which leads into a repeat of the original tempo, but calls for a softer registration of either an oboe or a trumpet as opposed to the full organ sound at the beginning. The piece alternates between the ostinato accompaniment softer theme and a fanfare motif. The ending registration calls for foundation stops. There is a syncopated rhythm in the pedals over sustained chords (all in octaves) leading to the ending chord which is a “tone cluster” sound which includes a G major chord overlapping with an a minor chord.

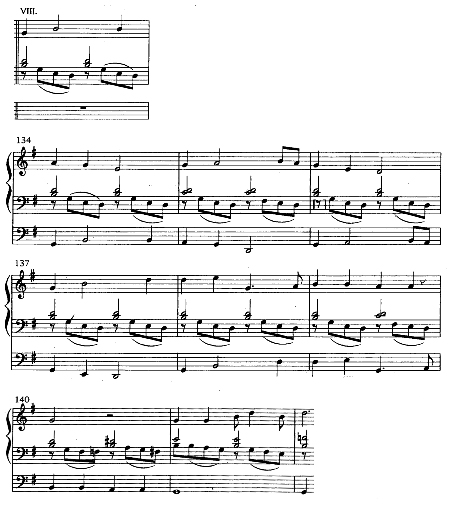

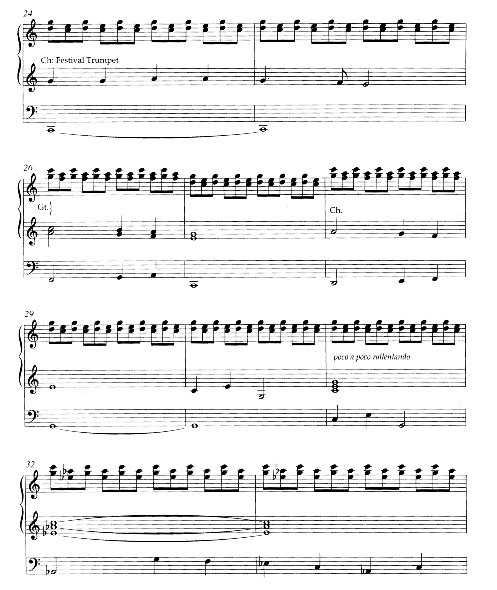

Nuptial Song is a slow, reflective piece that includes the use of chimes. It provides a stark contrast to the Processional (see Figure 7). The basic form is ABCA Coda. It begins with a solo melody over soft, chromatic chords, which is repeated near the end of the song. The middle section is the statement of a new melody with large leaps, repeated in thirds (B section). The C section is another new melody played both on the manuals and repeated as a pedal solo. After the return to A, the piece ends with a soft chordal section which diminishes to a quiet C major chord.

Figure 7. Nuptial Song from Nuptial Suite by Betty Jackson King.

Recessional reverts back to the same style as Processional, with a three-measure introduction marked “Brisk,” which leads to “Maestoso.” This section includes many of the rhythmic features of the Processional, and the recurrence of octave reaches in the manuals. There is a sixteen-measure soft section for the flutes and strings, which leads to the “Grandioso.” This section indicates the addition of a sixteen foot stop on the manuals and includes more octave reaches. Finally, the “Furioso” ending is a repetition of the rhythm from the beginning of the Processional, and calls for the addition of a pedal reed. The piece ends on a C major chord.

Helen Walker-Hill has stated, “Betty Jackson King was a product of the early Chicago classical music tradition (much like Margaret Bonds).” 63 She wrote works for solo piano, solo organ, solo voice, as well as art songs, choral works, and arrangements of spirituals. King's style is known for its extended harmonic language, thick massive chord clusters, and simultaneous layers of sound.64 Much of her music reflects her religious faith. Hildred Roach describes her style in this way: “Although King uses tonalism, her employment of fourths, fifths, and octaves along with skillful repetition, imitation, and echoes within familiar spirituals are effective and compact ... [and] her works range in intensity and insight.”65 See Appendix for more publication data. There are twenty-five scores of King’s works held at The American Music Research Center (AMRC) and The Center for Black Music Research (CBMR). Nuptial Song is published by the Jacksonian Press, Inc. (1969) (see Appendix).

Shirley Scott (1934-2002)

Jazz organist Shirley Scott was born and died in Philadelphia. She started out playing the piano and trumpet. In the mid-1950s, she was playing the piano in night clubs. “A club owner needed her to fill in on organ one night and the young Shirley took to it immediately, crafting a swinging, signature sound unlike anyone else almost from the get go.”66 She recorded for Prestige Records with Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis (1922-86). She was married to Stanley Turrentine (1961-71), a tenor saxophone player, and they played and recorded music together. She performed on electronic organs (ex. Hammond B-3). “Her playing consistently possessed one of the most graceful and lyrical touches applied to the bulky B-3. But it was her deeply-felt understanding of blues and gospel that made her playing most remarkable.”67 “Her reputation was cemented during the 1960s on several superb, soulful organ/soul-jazz dates where she demonstrated an aggressive, highly rhythmic attack blending intricate bebop harmonies with bluesy melodies and a gospel influence.”68 In popular music circles, Scott has been labeled the “Queen of the Organ.”

Helen Walker-Hill has listed a collection of organ solos written by Scott entitled Great Scott, published by Bradley Music in New York, 1977. This includes (1) Basie in mind; (2) Big George; (3) Blues everywhere; (4) Cherokee; (5) Little girl blues; (6) Merv’s theme; (7) My romance; (8) What is there to say?; and (9) What makes Harold sing? This collection can be found at the Library of Congress in the Music Division, Washington, DC. See Appendix for a listing of Scott's organ solos.

Judith Marie Baity (b. 1944)

Judith Baity, born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, received a Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree in Music Theory and Composition from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (1990), a Master of Music in Composition from Michigan State University, and a Certificate in Advanced Studies in Scoring for Motion Pictures and Television from the University of Southern California. She is now living and working in Los Angeles, California.

Intermezzo for Organ was commissioned by First Church of Christian Scientists, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.69 The name of the piece has been changed to A Whimsical Intermezzo and was published by Celestial Melodies Publishing in 2005. Baity states that the piece was commissioned by a friend of hers. Considering herself primarily a choral composer, Baity has not written any other organ compositions.70

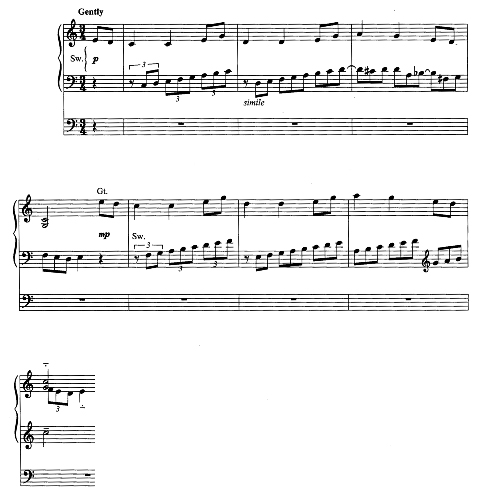

A Whimsical Intermezzo could be described as a frolic through many keys on the organ. After the seven-measure mezzo forte opening in 4/4 meter, the meter changes quite often throughout the piece. The piece is registered for mainly a flute sound with a light reed (oboe) and does not go to a forte (addition of a Principal 8') until right before the pianissimo ending. There is a section for the manuals alone, and a pedal solo section. After a gradual ritardando to the forte section, there is a definite pause before the seven-measure ending, which is in b flat minor. The piece ends with the pedals repeating the main rhythm pattern in the last two measures (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. A Whimsical Intermezzo by Judith Marie Baity.

On her website (www.celestial-melodies.com), in the biographical section named “About Judy,” it states, “In her career as a musician and composer, Judith has demonstrated her versatility and range in a number of musical genres and styles. As a musician, she has accompanied numerous choral organizations, and taught piano for many years. As a composer and arranger with a core foundation in classical as well as traditional and contemporary sacred music, Judith adds a unique musical voice to solo instrumental and orchestral compositions, choral works, jazz pieces and contemporary gospel music.”71 Baity is a member of the American Society of Composers, Authors & Publishers (ASCAP), and the International Alliance of Women in Music. See Appendix for publication information.

Sharon J. Willis (b. 1949)

Sharon J. Willis was born in Cleveland, Ohio, because her parents had moved north—as had other black families—in hopes of a better life. At age eleven, her parents separated and she and her sister (age six) moved to Atlanta, Georgia, to live with their maternal aunt, Lillie Mae Thrasher, who introduced them to church life. Willis was inspired by the pianist that played for her Sunday School class, even though she “missed every other note.”72 At age thirteen, Willis volunteered to play the piano for a talent show at a summer camp, even though she had never played the instrument before. Willis describes what happened:

I thought that the mere desire to play would be enough for me to be rewarded by God, who would magically put music into fingers at the designated time allowing me to astonish the audience. There was never a rehearsal, just the program. My aunt was ... truly astonished when they called my name to play the piano. I ... summoned God for the last time, raised my hands to the piano as I had seen my elementary school music teacher do and commenced to playing notes all over the piano. ... When I left the stage, the coordinator asked: Baby, what happened? You couldn’t find your key? I shyly answered: No m’am.73

After this incident, her aunt found her a piano teacher named Miss Daisy White. She then became the Sunday School pianist, and her musical career had begun.

Willis attended school and pursued her career mostly in Atlanta, Georgia. She attended Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University) (Bachelor of Music, Voice and Theory), Georgia Sate University (Master of Music in Theory), Scarritt Graduate School in Nashville, Tennessee (Master of Church Music, Conducting), and the University of Georgia (Doctorate in Vocal Performance). She taught at Agnes Scott College and Atlanta Metropolitan College. She was also an Associate Professor of Music and Liberal Arts Chair at Morris Brown College in Atlanta, Georgia. She has held numerous directorships in Music Ministry in the Atlanta area. Her current position is Associate Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music at Clark Atlanta University. “She is also well-established as a composer, soprano, lecture-recital artist, voice teacher, poet, and African American Program specialist.”74

“As a composer, Dr. Willis has written many spiritual arrangements, [Afro-]centric dramas and short plays, classical art songs, and poetry.”75 Willis is also invited regularly by colleges, universities, and churches to speak about her compositions and perspective as a woman composer and as an African American.

When speaking about her style, Dr. Willis firmly states she is more interested in expressing her message than in stating the theoretical analysis of her work. Her music is programmatic. “I infuse my message into the music.”76 She likes to compose when she is commissioned to write for a specific purpose or event, preferring not to write music as an exercise. She is passionate about historical subjects, particularly African American history.77 Most of her music includes spirituals interwoven into the music, a practice she explored in her doctoral dissertation entitled “The Use of Spiritual Melody in Selected Art Songs of Twentieth-Century Black American Composers” (University of Georgia, 1988).

Willis’s published organ works include: Exodus: Suite for Organ, The Journey Suite: Tone Poem for Organ, We Shall Overcome: Suite for Solo Organ, and The Agora Sacred Suite for Organ. Each of these works includes an in-depth explanation of the historical and musical significance of its material, written by Willis. This adds insight and emotion into the interpretation of the music. Exodus: Suite for Organ is written as a tribute to Harriet Tubman, who was born a slave around 1820 on the Brodas Plantation in Tidewater, Maryland. She escaped by way of the Underground Railroad to Philadelphia in 1849. In 1851, after working as a cook and a nurse, she was able to return to Maryland and Virginia to rescue her family and other passengers from slavery. In Tubman's words: “Ah nevuh lost a passenguh an’ Ah nevuh run my train off de track.”78 Tubman was called the “black Moses” as she led passengers to freedom, much in the same way Moses led the Hebrews from the bondage of slavery out of Egypt to the land of Canaan in the second book of the Bible in the Old Testament, Exodus. Exodus: Suite for Organ was dedicated to Trey Clegg, an organist and friend of Willis. The work is in three parts: (1) Chronicles: Passacaglia, (2) Communion: Rite of Fellowship, and (3) Celebration: Juba. Chronicles upon a Passacaglia is written in the musical form of passacaglia, in which a theme is repeated in the bass line against harmonic variations in the upper parts. Chronicles is a musical attempt to record Tubman’s journey of her repeated trips by underground. The spirituals Fare Ye Well, Wade in de Water, and Go Down Moses are used throughout this piece. There is an active pedal part consisting of sixteenth notes and rests which includes large leaps and scale passages. There is also a passage for thirds in the pedals. The whole piece is to be played loudly. This all gives the impression of anxious movement, which corresponds to the theme of the work. Communion a Rite of Fellowship uses the spirituals Drinking of the Wine and Let Us Break Bread Together. It is basically in ABA form, beginning and ending softly on the Drinking of the Wine melody in the key of e minor. It goes to the Let Us Break Bread Together theme in the key of E major, and leads to a section in B major which includes playing fifths in the pedal part before returning to the A section in e minor. Celebration on a Juba is based on the spiritual I Got A Robe. This is a joyous and happy piece in duple meter beginning in G major leading to a g minor section, and then to a loud, chordal E-flat major section which ends the piece. The juba was a dance performed by many African Americans during and after slavery. The dance was characterized by playing syncopated rhythms against even rhythms, a gesture that Willis captures well.

The Journey Suite: Tone Poem for Organ was written for Calvert Johnson, organist, when Dr. Willis was at Agnes Scott College. The work depicts the journey of African Americans. It is in rondo style and begins with children’s games. It depicts the story of the trip from Africa to America by way of the Middle Passage (Civil War, 1861). The three sections are: (1) Omorose: My Beautiful Child, (2) Pathos: An Ibo Meditation on the Middle Passage, and (3) Jubilee Festival March: A Celebration. The Pathos movement includes the spirituals Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child, Take Me to the Water, and Joshua fit de battle of Jerico. The Jubilee Festival March is a lengthy, joyous march.

We Shall Overcome: Suite for Solo Organ (published by Vivace Press, 2001) is a stirring and emotional four-movement piece depicting four important events from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Many familiar spirituals are included in each movement. For example, the last movement starts softly with chimes and soft stops on the tune There is a Balm in Gilead (see Figure 9) and ends with an exciting loud, slow version of We Shall Overcome that cannot help but move listeners (see Figure 10). See Appendix for a list of publications by Sharon J. Willis.

Figure 9. There is a Balm in Gilead from We Shall Overcome: Suite for Solo Organ by Sharon J. Willis.

Figure 10. We Shall Overcome from We Shall Overcome: Suite for Solo Organ by Sharon J. Willis.

Eurydice V. Osterman (b.1950)

Eurydice V. Osterman is a native of Atlanta, Georgia. She earned both the Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan, and taught at Berean SDA (Seventh-day Adventist) School in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and at Mt. Vernon Academy in Ohio (1972-1976). She earned the Doctor of Musical Arts degree from The University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa in composition (1988). Osterman currently is Professor of Music at Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama. Osterman has also served as Dean of the Greater Huntsville Chapter of the AGO (American Guild of Organists), and is a member of the International Adventist Musicians Association (IAMA).

Dr. Osterman has conducted music seminars in the United States, Europe, South America and Africa, and is a published author. Her publications include the book What God Says About Music, and is one of seven contributors to the book The Christian and Rock Music: A Study of Biblical Principles of Music (Chapter 12, “Rock Music and Culture”).79 Her compositions include music for the University of Alabama Symphony Orchestra, the General Conference Session of Seventh-day Adventists, and the London Chorale on BBC. Her awards for composition include being the first place winner in the 1994 and 1996 American Guild of Organists Greater Huntsville, Alabama Chapter Composition Competitions.

Osterman’s “works include keyboard, instrumental, and choral pieces which have been performed on Alabama Public Television, the Southern Chapter College Music Society Conference, the Presidential Inauguration at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Festival of Women Composers, and choral concerts in many parts of the United States. She has been invited to write music for performance and publication in various anthologies featuring African American women composers.”80 Osterman states that her early music style is different from her later style.81 The earlier works reflect the influence of her classical, traditional training. Her classical organ works are now published in a collection called Collage for Organ, which includes Aria, Gloria, Meditation, Passacaglia and Fugue, March Triumphant and Fantasia.

Aria in G major is homophonic, the melody played on the right hand and accompanied by chords in the left hand. For most of the piece, the pedal part consists of repeated quarter notes aligned with the chords in the left hand. Even though the title is Aria, this piece could be construed as a march with the 4/4 time-signature. Gloria and March Triumphant, in A major, would be useful in playing a Prelude or a Postlude in church music. Meditation is marked “Largo, very expressive,” but is dissonant, compared to other works written by Osterman. It has a plaintive melody and ends with chimes. Passacaglia and Fugue begins in D minor with a chordal statement of the passacaglia theme. The theme is then played in the right hand with an accompaniment in the left hand, which is then reversed in the next statement of the theme. This leads to a loud section in which the melody is played in the pedals with rolled, arpeggio chords on the manuals. This followed by a section which modulates into A minor. The melody is again played in the pedal part and the piece ends in A major. The Fugue is in D minor and starts simply with a statement of the subject and builds and becomes chromatic and employs sixteenth notes. It is a technical challenge with its chromaticism and sixteenth note passages, both in the manuals and the pedals.

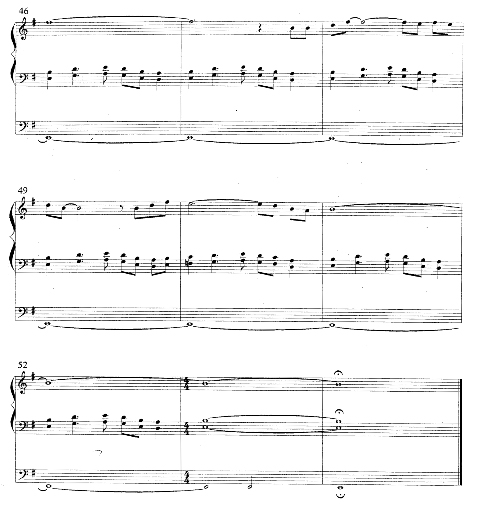

Another collection by Osterman is entitled Organ Meditations which includes variations on hymn tunes: Amazing Grace, Poor Wayfaring Stranger, Prelude on ‘Hyfrydol,' Give Me Jesus, Fanfare on Darwell's 148th, and Holy, Holy, Holy. She has also written a duet for organ and piano on When Morning Gilds the Sky. Amazing Grace begins with both hands played on the Swell, with a string sound. This passage is repeated in between each new variation of the tune. The melody is first stated on the Great as a solo, and then repeated in the pedal part in various keys. This piece is in D major, modulates to F major, and then returns to D major. There are passages for octaves in the pedals, as well as a statement of the melody in octaves at the end. Poor Wayfaring Stranger, in 5/4 time, is a beautiful setting of the hymn (see Figure 11). It has a haunting and mysterious sound. The accompaniment parts are distinct melodies within themselves, and therefore add to the delightful nature of the work. When Morning Gilds the Sky is a moving arrangement of the hymn for piano and organ, beginning with arpeggios for the piano over the melody played on the organ.

Figure 11. Poor Wayfaring Stranger by Eurydice V. Osterman.

Osterman has developed her own publishing company, AWSAHM Music, which is located in Huntsville, Alabama. All of the works listed above have been published by this company. See Appendix for publication information on Eurydice V. Osterman's works.

Regina Harris Baiocchi (b. 1956)

Regina Harris Baiocchi was born in Chicago, Illinois, and is a prolific composer for piano, drums, clarinet, voice, organ, and many other instruments. She is also known as a writer of poetry, short stories, and even a novel entitled Indigo Sound (2003). Baiocchi was raised in a large household in the housing projects of Chicago’s south side.82 Her mother, Lanzie Mozell Belmont Harris, loved organ music and studied organ. Her father was Elgie Harris, Sr. After attending high schools, Baiocchi enrolled in Paul Lawrence Dunbar Vocational High School and continued her music education by studying counterpoint, theory, arranging, and composition. She also sang in the chorus and played trumpet, French horn, and coronet in several of the school bands.83 Her education continued at Roosevelt University, B.M., 1978; coursework at Illinois Institute of Technology, 1984–86; coursework at Northwest University, 1990–92; New York University, certificate in public relations, 1991; and De Paul University, MM, 1995.

She also held teaching positions at several schools. Since January 2000, Baiocchi has been teaching Music Appreciation, African-American Literature, and English composition at East-West University in Chicago. Doxology (2011), her only organ work, is dedicated to her mother. The following is her description of the music:

Framed by tubular chimes, this homage opens with an interpolated scale, circle of 5ths ... and chorale. ... Thematic explorations showcase the organ and organist's dexterity through layers of orchestral sounds. ... A trumpet fanfare dissolves into a lone middle C, announcing the choral recapitulation ... and tubular chimes codetta .... 84

Looking at the future optimistically, Baiocchi will write more organ music to add to her repertoire of works for other genres.

Conclusion

Organ music written by African American women composers corresponds to social change within United States history, women's history, and music history. Therefore, the compositions draw from numerous sources, not just from Negro spirituals and folk songs. African American women organ composers shared some of the same challenges as other women. Getting their music heard was especially confounding, but teaching in all black colleges where Negro Spirituals and folk songs were standard and by writing church music, women identified areas that were socially acceptable for their musical expression. History also opened doors for their music. African American women were able to extend their reach because of events such as the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and women's liberation in the latter part of the 20th century. Technological advancements also helped African American women, as well as all composers, reach a broader audience. In 2004, when research on this article began, many of the works discussed in this paper were not published, but they are now. Composers have developed their own publishing companies to disseminate their music, as listed in the Appendix. In the future, this music will be part of standard organ repertoire, not unknown as it was in earlier centuries.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abdul, Raoul. Blacks in Classical Music: A Personal History. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1977.

Ammer, Christine. Unsung: A History of Women in American Music. Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 2001.

Anderson, Ruth E. Contemporary American Composers: A Biographical Dictionary, 2nd ed. Boston, Massachusetts: G. K. Hall & Co., 1982.

Baiocchi, Regina Harris. Doxology. Chicago, Illinois, ASCAP, 2011.

Baity, Judith M. A Whimsical Intermezzo. Sherman Oaks, California: Celestial Melodies, 2005.

Beckmann, Klaus. Repertorium Orgelmusik—A Bio-Bibliographical Index of Organ Music: Composers - Works - Editions 1150-2000—57 Countries; Band/Volume 1/Organ Solo. Mainz (printed in Germany), 2001.

Bethune-Cookman College. “Inaugural B-CC Performing Arts Center Concert Features World Premiere.” Accessed December 19, 2004. http://www2.cookman.edu/Development/Media_release/2003/20030923.htm.

Biblical Perspectives. The Christian and Rock Music: A Study of Biblical Principles of Music: (Chapter 12, “Rock Music and Culture”). Accessed December 22, 2004. http://www.biblicalperspectives.com/rockbook/DESCRIPTION_ORDER_INF.html.

Boston, Bruce O. “Tapping Into our Musical Heritage.” Teaching Music, Vol. 3, n6 (1996): 42-43.

Bowers, Violet George. “African American Composers.” The Organ, Vol. 80 (May-July 2001): 74-76.

Celestial Melodies Publishing, “Judith M. Baity: Biography.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.celestial-melodies.com/bio.php.

Floyd, Samuel A. Jr., ed. Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

_____. Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance: A Collection of Essays. New York: Greenwood, 1990.

_____. International Dictionary of Black Composers. 2 vols. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1999.

Green, Mildred Denby. Black Women Composers: A Genesis. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1983.

Hare, Maud Cuney. Negro Musicians and Their Music. London: Prentice Hall International, 1996. Reprint of 1936 edition with introduction by Josephine Harreld Love. New York: G. K. Hall & Co.: An Imprint of Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Harrell, Paula Denise. “Organ Literature of Twentieth-Century Black Composers: An Annotated Bibliography.” D.M.A. diss., The University of North Carolina, 1992.

Henderson, Alex and Ron Wynn. “All Music Guide.” Accessed December 10, 2004. http://www.mp3.com/shirley-scott/artists/6359/biography.html.

Horne, Aaron. Keyboard Music of Black Composers: A Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1992.

Hubler, Lyn. “Three Unknown Organ Composers.” The American Organist, Vol. 19 (August 1985): 50-51.

Jacksonian Press, Inc. “Celebration of the Life and Music Ministry of Betty Jackson King.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.bettyjacksonking.com.

Johnson, Calvert. “Florence Price: Chicago Renaissance Woman.” The American Organist, Vol. 34 (January 2000): 68-76.

_____. Music of Florence Beatrice Price, Vol. 2. Short Organ Works. Fayetteville, AR: ClarNan Editions CN24, 1995.

_____. Music of Florence Beatrice Price, Vol. 3. “Variations on a Folksong (Peter, Go Ring Dem Bells)” for organ. Fayetteville, AR: ClarNan Editions CN26, 1996.

Leonarda Productions. “Alphabetical Composer Bios (N-Q).” Accessed October 10, 2013. http://www.leonarda.com/compnq.html.

Leonarda Productions. “Kaleidoscope: Music by African-American Women.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.leonarda.com/composers-LE/comp339.html.

McGinty, Doris Evans, ed. A Documentary History of the National Association of Negro Musicians. Chicago: Center for Black Music Research, Columbia College Chicago, 2004.

McGinty, Doris Evans. “From the Classics to Broadway to Swing,” Black Perspective in Music, Vol. 16/1 (Spring 1988): 81-104.

Nichols, Janet. Women Music Makers. New York: Walker and Company, 1992.

Payne, Doug. “Shirley Scott: A Discography.” Accessed December 10, 2004. http://www.dougpayne.com/shirley.htm.

Perkins, Holly Ellistine. Biographies of Black Composers and Songwriters: A Supplementary Textbook. Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers, 1990.

Pool, Jeannie Gayle. “The Life and Music of Zenobia Powell Perry: An American Composer.” Ph.D. diss., Claremont Graduate University, 2002.

Ritter, Carol. “Organ Music Written by African American Women,” D.M.A. diss., The American Conservatory of Music, 2005.

Roach, Hildred. Black American Music: Past and Present, 2nd ed. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company, 1992.

Sadie, Julie Anne and Rhian Samuel, eds. The Norton/Grove Dictionary of Women Composers. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1995.

Southern, Eileen. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Black Music: Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982.

_____. The Music of Black Americans: A History, 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

_____. Readings in Black American Music, 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1983.

Spencer, Jon Michael. Re-Searching Black Music. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

Terry, Mickey Thomas. “A Second Glance: An Overview of African-American Organ Literature.” The Diapason (May 1998): 18-21.

_____. “African-American Classical Organ Music: A Case of Neglect.” The American Organist Magazine (March 1997): 56-61.

_____. “African-American Organ Literature: A Selective Overview.” The Diapason (April, 1996): 14-17.

_____. African-American Organ Music Anthology, 5 vols. St. Louis: Morning Star Music Publishers.

Turner, Patricia. Dictionary of Afro-American Performers: 78 RPM and Cylinder Recordings of Opera, Choral Music, and Song, c. 1900-1949. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. 1990.

Walker-Hill, Helen. “Discovering the Music of Black Women Composers.” American Music Teacher, Vol. 40, n1 (1990): 22.

_____. From Spirituals to Symphonies: African-American Women Composers and Their Music. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

_____. Music by Black Women Composers: A Bibliography of Available Scores, CBMR Monographs, No. 5. Chicago: Columbia College, 1995.

Weathersby, Lucius. “Out of Africa.” The Organ, Vol. 79 (August-October 2000): 125-126.

West Virginia University News Release. “WVU Faculty Member Releases CD Featuring Works of Black Composer.” Accessed November 28, 2004. http://www.nis.wvu.edu/2003_Releases/peri_cd.htm.

Williams, Ora. American Black Women in the Arts and Social Sciences: A Bibliographic Survey. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1973.

Wisconsin Alliance for Composers. “Judith Baity.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.wiscomposers.org/archives/ 1997/19970425a.html.

Willis, Sharon J. Music by African-American Women: We Shall Overcome—Suite for Solo Organ. Stevens Point, WI: Vivace Press, 2001.

Appendix

Publication Information and Score Location of Organ Works by African American Composers Mentioned in this Article

Baiocchi, Regina Harris, Work for organ Doxology published in 2011 by ASCAP

Baity, Judith, Organ works published by Celestial Melodies Publishing (http://www.celestial-melodies.com/contact.html)

King, Betty Jackson, Jacksonian Press, Inc., Chicago, Illinois (http://www.bettyjacksonking.com/)

There are twenty-five scores of King’s works held at The American Music Research Center (AMRC) and The Center for Black Music Research (CBMR).

Moore, Undine Smith, A checklist of scores of Moore’s works can be found in the Helen Walker-Hill Collection at the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR), Columbia College, Chicago, and also at the American Music Research Center (AMRC), University of Colorado at Boulder. A complete list of compositions by Moore has also been compiled by her daughter, Mary Easter, from her personal collection (1990 Unpublished).

Osterman, Eurydice V., AWSAHM Music, in Huntsville, Alabama (http://www.awsahmmusic.com)

Prelude on ‘Hyfrydol’ was published in 1984 by AWSAHM Music.

Poor Wayfaring Stranger was published in 2002 by AWSAHM Music.

Perry, Zenobia Powell, Jaygayle Music Publications (Jaygaylemusic.com)

Two scores and music manscripts are found at the University of Chicago (uchicago.edu).

Price, Florence B., Archives of the music written by Florence Price are held at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Library, Manuscript Collection 988. Florence Price Robinson, daughter of Florence Price, donated her mother's papers to Special Collections in 1974. They include correspondence, musical scores, and other papers, 1906-1975.

Calvert Johnson has edited the following collections of music written by Florence Price:

Music of Florence Beatrice Price, Vol. 2. Short Organ Works. Fayetteville, AR: ClarNan Editions CN24, 1995.

Music of Florence Beatrice Price, Vol. 3. “Variations on a Folksong (Peter, Go Ring Dem Bells)” for organ. Fayetteville, AR: ClarNan Editions CN26, 1996.

Both of these editions include more information about the composer and her works than just the sheet music, including lists of organ works, registration, biographical information, etc.

Scott, Shirley, Helen Walker-Hill has listed a collection of organ solos written by Scott entitled Great Scott, published by Bradley Music in New York, 1977.74. This includes: (1) Basie in mind; (2) Big George; (3) Blues everywhere; (4) Cherokee; (5) Little girl blues; (6) Merv’s theme; (7) My romance; (8) What is there to say? and (9) What makes Harold sing? This collection can be found at the Library of Congress in the Music Division, Washington, D.C.

Willis, Sharon J., The organ works of Sharon J. Willis are published by: Vivace Press (http://www.vivacepress.com/) and Wayne Leupold Editions, Inc. (http://www.wayneleupold.com/)

Notes

1This paper is based on “Organ Music Written by African American Women” (Carol Ritter, Doctoral thesis, The American Conservatory of Music, 2005).

2Thomas Terry, “African-American Classical Organ Music,” 56.

3Ibid.

4Weathersby, “Out of Africa,” 125.

5Ibid., 57.

6Floyd, ed., Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance, 12.

7Ibid.

8Ibid., 71.

9Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History, 603.

10Trotter, Music and Some Highly Musical People (Boston: Author, 1878. Reprinted NY: Johnson Publishing, 1968). Quoted in Walker-Hill, From Spirituals to Symphonies, 21. Trotter’s book was the first to attempt a survey of a body of music in the United States. It was followed in 1883 by white author Frederick Louis Ritter’s Music in America. (Quoted from Walker-Hill, notes p. 43).

11Southern, The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Black Music, 312.

12Green, Black Women Composers: A Genesis, 31.

13Ammer, Unsung: A History of Women in American Music, 174.

14Green, Black Women Composers, 32.

15Floyd, Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance, 78.

16Nobert, Francis, Organist, Music She Wrote: Organ Compositions by Women, CD notes. (Raven OAR-550, 5.)

17Nichols, Women Music Makers, 124.

18Floyd, Black Music, 78.

19Ibid.

20Ammer, Unsung: A History, 174.

21Floyd, International Dictionary of Black Composers, 942.

22Turner, Dictionary of Afro-American Performers, 294.

23Floyd, International Dictionary, 942.

24Johnson, Chicago Renaissance Woman: Florence B. Price Organ Works, Calcante Recordings, Ithaca, New York CAL CD014 © 1997, 5.

25Ibid.

26Ibid.

27Green, Black Women Composers, 38.

28Johnson, Chicago Renaissance Woman, 5.

29Johnson, Music of Florence Beatrice Price, ix.

30Johnson, Music of Florence Beatrice Price, Vol. 2, xxv.

31Ibid.

32Johnson, Chicago Renaissance Woman, 5.

33Kimberly Marshall, “Divine Euterpre,” Quilisma, Loft Recordings LRCD1021, Notes. Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.quilimsa.com/system/index.html.

34Roach, Black American Music: Past and Present, 119.

35Hobart and William Smith Colleges: News Release, "Celebrate Black History Month.” Accessed May 5, 2004. http://www.hws.edu/news/update/showrelease.asp?id=3489.

36Floyd, International Dictionary, 941.

37Thomas Terry, African-American Organ Music Anthology, Vol.2, v.

38Holly Ellistine Perkins, Biographies of Black Composers and Songwriters: A Supplementary Textbook. Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers, 1990. Accessed July 11, 2004. http://www.uni.edu/taylord/pittman.bio.html.

39Boston,“Tapping Into our Musical Heritage,” 43.

40Ibid.

41Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 547.

42Ibid., 546.

43Thomas Terry, African-American Organ Music Anthology, Vol. 2, v.

44Harrell,“Organ Literature of Twentieth-Century Black Composers,” 59.

45Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 547.

46Thomas Terry, “African-American Classical Organ Music,” 57. Quotation from David N. Baker, Lida M. Belt, and Herman C. Hudson, eds., The Black Composer Speaks (Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1978).

47Roach, 135.

48Floyd, International Dictionary of Black Composers, 76.

49It is stated on Perry’s website that there has been a discrepancy in the date of her birth. Many sources indicate 1914 as her birthdate and this is incorrect (ex. Roach, Black American Music, p. 180; Walker-Hill, From Spirituals to Symphonies, 371). Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.zenobiaperry.org.

50Pool, “The Life and Music of Zenobia Powell Perry, 245.

51Ibid., 168. Interview with Pool, Morgantown, West Virginia, September 30, 2001.

52Ibid.

53Ibid., 177.

54Ibid.

55Ibid., 168.

56Ibid., 179.

57Ibid., 181.

58West Virginia University News Release, “WVU Faculty Member Releases Cd Featuring Works of Black Composer.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.zenobiapowellperry.org.

59Pool, 231.

60Ibid., 192-193.

61Jacksonian Press, Inc., “Celebration of the Life and Music Ministry of Betty Jackson King.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.bettyjacksonking.com.

62Ibid.

63Walker-Hill, From Spirituals to Symphonies, 35.

64Leonarda Productions, “Kaleidoscope: Music by African-American Women.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.leonarda.com/composers.

65Roach, 166.

66Payne, Doug, “Shirley Scott: A Discography.” Accessed December 10, 2004. http://www.dougpayne.com/shirley.htm. More information by Doug Payne about Shirley Scott can be found at http://www.dougpayne.com/shirley1.htm (accessed July 23, 2013).

67Ibid.

Alex Henderson and Ron Wynn, “All Music Guide.” Accessed December 10, 2004. http://www.mp3.com/shirley-scott/artists/6359/biography.html. More information on Shirley Scott's recording period between 1961-1968 can be found at http://www.bluenote.com/artists/shirley-scott (accessed July 3, 2013).

69Helen Walker-Hill, Music by Black Women Composers, 20.

70Personal e-mail from Judith Baity, December 21, 2004.

71Celestial Melodies Publishing, “Judith M. Baity: Biography.” Accessed July 3, 2013. http://www.celestial-melodies.com/about_judy.html.

72Personal notes from Sharon Willis.

73Ibid.

74Willis, We Shall Overcome—Suite for Solo Organ, back cover.

75Ibid.

76Interview with Dr. Willis, 22 December 2004.

77Ibid.

78Sharon Willis, “Composer’s Commentary” in notes on Exodus.

79Biblical Perspectives, The Christian and Rock Music: A Study of Biblical Principles of Music (Chapter 12, “Rock Music and Culture”), Accessed December 22, 2004. http://www.biblicalperspectives.com/rockbook/ DESCRIPTION_ORDER_INF.html.

80Oakwood College, “Profiles: Eurydice Osterman D.M.A.” Accessed December 23, 2004. http://www.oakwood.edu/ music/default.asp?ID=9#osterman.

81Personal telephone interview with Eurydice Osterman, December, 2004.

82“Baiocchi, Regina Harris 1956- .” Encyclopedia.com. Accessed July 2, 2013. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2874300013.html.

83Ibid.

84Doxology, by Regina Harris Baiocchi, 10.