Colleges and universities are under increasing pressure to develop online courses for a variety of classes that have traditionally been offered only through face-to-face (F2F) classroom instruction.1 The process of developing these online classes, as well as the challenges involved with implementing and supervising these non-traditional courses, provide a number of difficulties for the instructors and administrators who are given the task of creating new methods of delivery for traditional and established parts of the university curriculum. In the case of music theory and aural skills instruction, a special set of concerns and challenges are presented to the instructors, developers, and supervisors of these online courses. In this study, I examine some of the issues involved with the development, implementation, and supervision of online music theory courses by drawing upon the knowledge learned from similar challenges in related disciplines, an assessment of the current technology, and input from professional music theory instructors and university administrators who have practical experience with these issues. The primary focus of this study will directly relate to college and university music theory classes delivered entirely through online methods of instruction, rather than hybrid courses or classes that involve an “inverted” or “flipped” method of organization.

Development

The transformation of traditionally delivered music theory courses into online versions of either the same or equivalent university classes can be a difficult process for both instructors and administrators. During the development of these online courses a number of specific challenges often emerge as the most problematic issues for the course developers, while more general problems regarding the effective implementation of the new classes are met by administrators and supervisors. Some of the most significant issues involved with the development of online music theory courses include the following:

- The scale of the project in terms of the workload and time commitment for the developer or development team.

- Estimating the continuing faculty time commitment related to managing the online classroom

- The possible lack of experience among faculty members or instructors with the process of online course development.

- The difficulty of maintaining equivalency in terms of content and instructional strategies between the online and the traditionally delivered music theory classes.

- Estimating the technical difficulties that students will encounter during the course.

- Access to technical support and training for the course developers and instructors.

- Developing reliable online assessment materials and procedures.

- The ability of instructors to develop active strategies for maintaining engaged student participation during the course.

- Planning for issues related to student accessibility.

- Development of procedures and policies related to academic dishonesty and plagiarism.

Developing a new online music theory course will require a significant time commitment from the principal instructor or course developer. Stevens (2001) has described the process of converting a traditional college class into an equivalent online version. In that study the author recommends limiting the number of classes that any one developer or instructor should be tasked with converting to new online versions and allowing significant time for the conversion process. Bradley (2001) describes the process of creating a development team in which the task of pedagogical design is separated from an academic review of the new online course materials and procedures.

In addition to consideration of the time commitment involved with the process of developing the new online classes, instructors and supervisors need to make reasonable estimates concerning the amount of time that will be required to successfully manage the online virtual classroom (Mupinga & Maughan 2008). Often, the amount of preparation time and time spent in direct communication with students for an online class will far exceed the amount of time required from the instructor during an equivalent traditional face-to-face (F2F) class (Cavanaugh 2005). Another important aspect of the development process is consideration of the possible lack of experience on the part of some instructors in the area of teaching and developing online courses. The relatively steep learning curve in regard to both technical considerations and pedagogical methods will dramatically increase the amount of time required to effectively complete the process of developing new online courses in comparison to traditionally delivered classes.

During the process of development, the content of the original (F2F) class should be successfully translated to the new online class, despite the significant necessary changes in pedagogical methods. Although the primary responsibility for the content of the course will probably remain with the course instructor, Bradley (2001) has described a process in which an academic review team monitors the content of the newly developed online class for suitability and subject coverage. In the process described by Bradley, a general pedagogical framework was initially established by consensus agreement between instructors and the members of the review committee, after which the task of development was separated from the work of academic content review. The pedagogical framework established in Bradley’s study was derived from Kolb’s (1984) theory of experiential learning.2

Research suggests that online courses may not provide the range and intensity of support that students need to perform as well as they might in traditional (F2F) classes (Aragon & Johnson 2008), and that students generally underperform in online classes compared to the equivalent traditionally delivered courses (Hall 2008) (Urtel 2008). For this reason the developers of online classes must account for the level and quality of technical support that will be available to the students during the active period of the class, as well as the accessibility of tutoring services that might be provided for the students (Crawley 2012), especially for the students whose individual learning style would allow them to benefit from actively engaged methods of academic assistance (Mandernach 2009). The course developers must also account for the technical abilities of other faculty members and course instructors, taking into consideration the level of technical support and training that will be available or provided to the instructors.

Research has demonstrated that successful online instruction must include a substantial amount of interaction, both between students and between the students and the instructor (Clark- Ibáñez & Scott 2008). Incorporating effective methods of interaction is one of the primary challenges during the process of developing an online course. An important method for integrating meaningful interactivity into the development of online courses may be the use of asynchronous learning networks (ALNs) such as threaded discussions, progressive writing assignments, and group wikis (Driscoll 2012).

Issues related to academic dishonesty are often considered to be a more significant problem in online courses than in the corresponding F2F versions of the same classes, especially in the area of testing and evaluation.3 It is important that the developer of an online music theory course carefully consider the issue of academic dishonesty when creating the format and procedures of the tests and other evaluative materials that will be used during the class. Research has suggested that the best practice for minimizing or discouraging academic dishonesty in an online course is to carefully and thoughtfully develop the testing material in order to reduce the opportunities for cheating (such as using open book or research based test questions, or requiring students to answer open ended “thought-questions”) and increasing student awareness of the importance of academic integrity (Conway-Klaassen & Keil 2010).

Other important considerations during the process of development include the accessibility of the online course for students with disabilities and the possibility of requiring a mandatory face-to-face orientation session before being allowed to enroll in the course. Research has shown that the level of accessibility for students with disabilities may have a profound effect on the students’ level of engagement, academic performance, and completion rate (Betts 2013). Research has also shown that a mandatory orientation session for students who enroll in online classes results in students feeling better prepared for their online courses and results in improved student retention (Jones 2013).

Implementation

Perhaps the most significant consideration for the successful implementation of an online music theory course is the intense time commitment from the instructor that will be required to deliver the content material as effectively through the medium of the virtual classroom as it would have been delivered through a traditional face-to-face (F2F) class (Van de Vord & Pogue 2012). In addition to the time spent preparing for class or directly engaging with the students, the instructor must also allow for significant time to be allocated for the necessary technical training or self-directed learning that will be needed for the instructor to become proficient with the instructional software and pedagogical design of the course. Some instructors may adapt easily to the paradigm shift from traditional pedagogical procedures to the new procedures and practices of the online virtual classroom, while others may face significant challenges or difficulties in making this adjustment (Yu & Brandenburg 2006). Important aspects to consider during the implementation of an online music theory course include the following:

- The pedagogical strengths and weaknesses of the “learning management system” or LMS.

- The ability of the students to effectively access the LMS.

- Compatibility of the LMS to the traditional methods of teaching the class, including aspects such as homework assignments and assessment.

- Time management issues for the instructor.

- The availability and effectiveness of technical support for students.

- The availability and effectiveness of technical support for the instructor.

- The availability of an orientation session for the students

- Accommodations for students with disabilities

- Scheduling faculty preparation time and time directly engaging with students.

- Retention efforts.

One of the most important aspects of the successful implementation of an online music theory course is the instructor’s familiarity and knowledge of the “learning management system,” or LMS. Since most of the activity during the class may be enacted through the LMS software, the instructor must be adequately trained and proficient with the LMS system before beginning the process of developing the class. The capabilities of the LMS system, including its pedagogical strengths and weaknesses, should be an integrated part of the instructional design of the course.

Perhaps the most significant contributing factor to the general user experience from the viewpoint of the students in an online music theory class will derive from the usability and functionality of the LMS software. Often the selection of the LMS software is determined at the campus, system, or university level. Top-level administrators may have a better awareness of the technical aspects of LMS software than they do of the more practical educational and pedagogical aspects of these systems (Ellis & Calvo 2007). In some cases department level administrators, or instructors, may have the option of choosing between two or more LMS software packages when developing or teaching an individual course. In 2013, BLACKBOARD,4 the most widely used commercially available LMS system, maintained a 41% market share,5 although a number of competing systems were rapidly gaining new customers. Early versions of BLACKBOARD were widely reported to incur serious, and at times critical, usability problems, especially for the instructors and developers who attempted to use the system to deliver innovative methods of content delivery to the students. The CANVAS6 learning management system is rapidly expanding to many colleges and universities and provides a flexible platform for the development and implementation of complex or creative instructional approaches or procedures. CANVAS is a comprehensive cloud-native software package that delivers an intuitive and user-friendly interface.

Instructors of entirely online classes must establish clear expectations in regard to how the students are to complete assignments and participate in class activities (Angelino, 2007). These expectations must also take into consideration the capabilities of the LMS software and include clear and workable instructions concerning the use of the LMS in all required coursework. Since many of the assignments in the virtual classroom involve asynchronous methods of learning, the instructor must clearly communicate the deadlines for all coursework related assignments.

Instructors should be flexible in response to the feedback that may come from students during the active period of the course (Gallien & Oomen-Early 2008). If the course has not been offered previously as an online class there will likely be a number of procedures or teaching strategies that students will encounter for the first time during the class. The response of the students during the active period of the course provides a valuable source of information in regard to both the effectiveness of the pedagogical strategies that were chosen during the process of course development and the effectiveness of the LMS software to deliver the content material to the students.

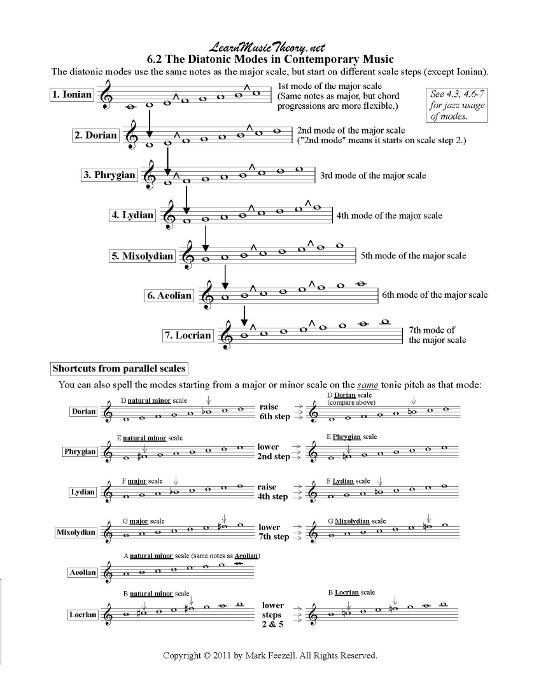

There are currently [as of May 2016] no commercially available courseware packages for college or university level music theory classes that are intended to be used as the primary electronic textbook for an entirely online method of delivery and that are designed to seamlessly integrate with the most widely used LMS software. The instructors of online music theory classes are usually expected to develop the majority of the teaching materials that will be used during these classes. There are a number of free web-based resources that provide content material for music theory instruction, including “musictheory.net,” “musictheoryblog.blogspot.com,” “basicmusictheory.com,” and “teoria.com.” Perhaps the best free online source for music theory instructional material is the comprehensive collection of web-based lessons created by Dr. Mark Feezell of Southern Methodist University that is available at “learnmusictheory.net.”7 Example 18 provides a sample lesson from “learnmusictheory.net.”

Commercially available software packages that are designed to be used by students independently may be integrated into the curriculum of an entirely online music theory course; however, the instructor of the class must carefully plan for the absence of seamless integration between the instructional strategies and methods of the primary coursework and the teaching strategies and terminology used by the independent software package. In addition, the work produced by the student in the independent software package will probably not be designed or intended to be evaluated by the instructor, but rather will be based upon an internal self-graded system, which may conflict with the design of the online music theory class in regard to both technical terminology as well as the overall instructional design of the course.

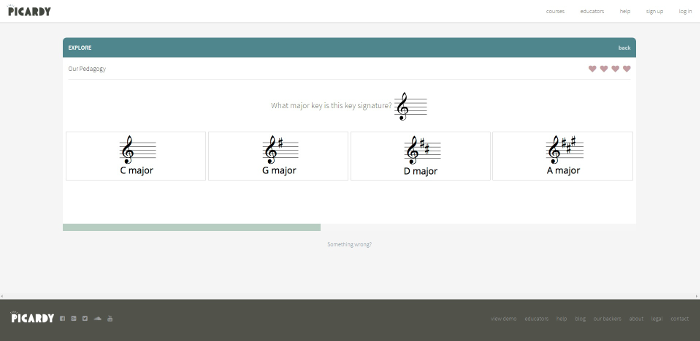

Some of the most widely distributed commercial music theory instructional packages include Alfred’s Essentials of Music Theory,9MacGAMUT,10 and Auralia.11 None of these commercially available software packages, with the possible exception of the more recent versions of Auralia, were specifically designed to be used as part of a college or university music theory course.12 Picardy13 is an instructional software platform that has been specifically designed to work effectively in connection with a college or university music theory curriculum. Picardy is a web-based subscription service, primarily intended for instruction in musicianship and aural skills, that delivers a customizable learning platform with student progress information for the instructor and a user-friendly interface for the students. Example 214 provides a sample screenshot from the Picardy software platform.

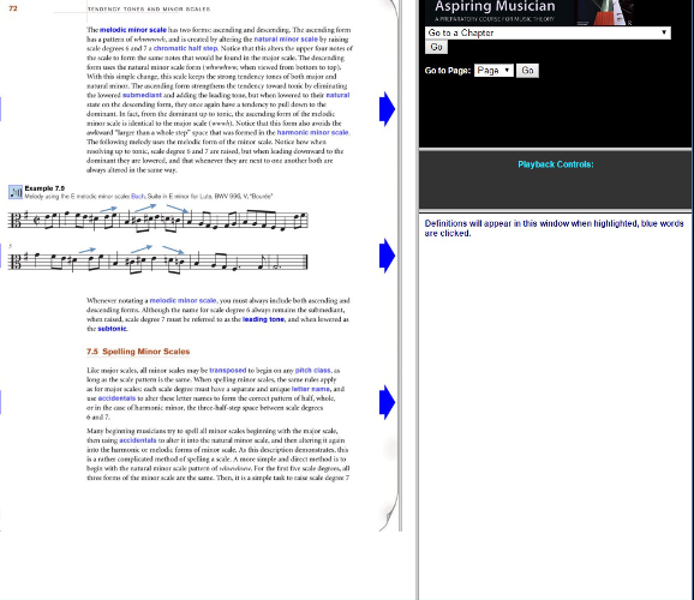

An electronic textbook that is intended specifically for the use of college and university music theory classes is Fundamentals for the Aspiring Musician, developed by Robert J. Frank and Ken Metz, and published by Routledge. This electronic textbook includes extensive use of hypertext instructional links, quality recordings of examples performed by professional musicians, and a comprehensive collection of lessons that are compatible with an entirely online music fundamentals or first-semester music theory class. Example 315 provides part of a sample lesson from Fundamentals for the Aspiring Musician.

Supervision

As institutions of higher education attempt to maintain their competitive standing in the learning environment of the twenty-first century, administrators will need to adapt to a variety of delivery methods for the creation, transmission, and application of knowledge. As new technologies are developed and integrated, new challenges will be met by academic departments and the supervisors who manage and lead these institutions. Among the most significant issues for supervisors who are attempting to establish a newly developed online music theory course would be the following:

- Maintaining the equivalency of content material between online and traditionally delivered versions of the same courses.

- Assessment of the main issues that are emphasized in student feedback.

- Being aware of difficulties, both technical and pedagogical, that are encountered by instructors.

- Assessment of the availability and the quality of technical support.

- Assessment of the technical reliability of the LMS and other learning technology.

- Observation or review of the instructor during the active period of the class.

- Assessment of the time requirements imposed by the online virtual classroom upon the students and the instructor.

- Assessment of the perceived difficulty of the class for students.

- Assessment of the expectations of both students and instructors and assessing how these expectations are either being met or altered during the active period of the course.

- Assessment of the reasons for negative student outcomes.

Perhaps the most important responsibility for the administrative supervisor of an online music theory course concerns the relatively poor academic results achieved by some students in contrast to the normal expectations for academic performance in the traditional face-to-face (F2F) versions of these classes. Administrators must insure that the online courses provide the same academic content as the traditionally delivered classes and that the newly delivered pedagogical strategies for the virtual classroom deliver the same learning opportunities as the original courses (Orellana 2006). Since many students underperform in online classes (Nash 2005) (Urtel 2008), college and university administrators must carefully monitor a newly developed online music theory course to assess the relative level of student academic success.

Administrators may consider some method of student-based evaluation of the course or the instructor during the active period of the class. Gathering feedback from the students may provide an important source of information about the effectiveness of the teaching methods used during the class as well as the accessibility and reliability of the instructional software. Administrators must also be aware that online classes are frequently evaluated more poorly than F2F sections of the same classes (Summers 2005) and that student evaluations are strongly affected by the teaching style and personality of the instructor (Williams & Ceci 1997) (Landrum & Dillinger 2004).

Success in online courses requires a range of technical and academic skills that some students may be lacking at the time when they first enroll in the class (Williams 2003). To address this need, administrators should consider making readiness activities, such as a mandatory orientation session, a requirement prior to registration for an online course (Jones 2013). Readiness activities should integrate technical training with an explanation of the behavioral expectations, such as time management skills and strategies for completing class assignments, that will be needed to be successful in an online virtual classroom.

In order to insure the success of a newly developed online music theory course, administrators may consider some methods for screening or limiting the students who are allowed to enroll in online sections, such as establishing a GPA requirement. This may direct students away from the online sections who are likely to be unsuccessful in those classes, or likely to withdraw early. Students who have not previously established a record of academic success are more likely to experience a negative outcome in an online class (Urtel 2008). Administrators may also consider eliminating sections of online classes that tend to repeatedly underperform.

Administrators may also consider the establishment of an “early warning system” for students who are not performing well in an online music theory course. This may be an automated process as part of the LMS software, or it may be initiated by the instructor. Since the existing retention policies and procedures of many colleges and universities are not well suited to the needs of online students, administrators may need to develop new guidelines to minimize the number of students who “drop out” of online classes. Technical support, especially online or telephone based technical support, should be available for both students and instructors. Training sessions and professional development should be available for instructors. A systematic review process should be in place to insure that the content of the course meets the academic standards of the department.

Conclusion

The possibility of providing online music theory classes holds great promise for college and university music departments. At present it still remains a challenge to maintain an optimal student learning experience in music theory courses in the online virtual classroom, at least in comparison to the traditionally delivered face-to-face versions of these classes. Through comprehensive and sustained efforts at improvement and regular pedagogical review, instructors and administrators may soon be able to reliably offer online music theory courses that provide students with an academic experience that is fully equivalent to the traditional modes of instruction.

Notes

1In recent years it has been estimated that 30 percent of higher education students take at least one online course during their academic career and that enrollment in online courses is increasing at a substantially faster rate than overall higher education (Allen 2010).

2For a discussion of the process of developing music theory instructional material in terms of Kolb’s (1984) theory of experiential learning, see Lively (2005).

3Research suggests that the concept of “cheating” and academic integrity is rapidly evolving among college and university students, especially in relation to internet-based testing (Grijalva 2008).

4Developed by Backboad Inc.

5As reported in the October 2013 edition of Campus Computing.

6Developed by Instructure.

7There is also an online anthology of musical works available at LearnMusic Theory.net.

8© Mark Feezell, 2011. Used by permission.

9Developed by Alfred Music.

10Developed by MacGAMUT Music Software International.

11Developed by Rising Software.

12A review of music theory instructional apps for smart phones has been provided by Nathan Fleshner (2014).

13Developed by Picardy, LLC.

14Used by permission of Picardy, LLC.

15© Routledge/Taylor and Francis, 2010. Used by permission.

Bibliography

Allen, I. & Associates. 2010. Class Differences: Online Education in the United States. The Sloan Consortium.

Angelino, L. M., & Associates. 2007. “Strategies to Engage Online Students and Reduce Attrition Rates.” The Journal of Educators Online 4 (2): 1-14.

Aragon, S. R., & Johnson, E. S. 2008. “Factors Influencing Completion and Noncompletion of Community College Online Courses.” The American Journal of Distance Education 22: 146-58.

Betts, Kristen, & Associates. 2013. “Strategies to Increase Online Student Success for Students with Disabilities.” Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 17 (3): 49-63.

Bradley, Claire. 2001. “The Development of An Online Course for a Virtual University.” Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications. ED 466140.

Cavanaugh, J. 2005. “Teaching Online: A Time Comparison.” Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration 8.

Clark-Ibáñez, Marisol & Scott, Linda. 2008. “Learning to Teach Online.” Teaching Sociology 36 (1): 34-41.

Conway-Klaassen, Janice M. & Keil, Deborah E. 2010. “Discouraging Academic Dishonesty in Online Courses.” Clinical Laboratory Science 23 (4): 194-200.

Crawley, A. 2012. Supporting Online Students: A Guide to Planning, Implementing, and Evaluating Services. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

Driscoll, Adam & Associates. 2012. “Can Online Courses Deliver In-class Results? A Comparison of Student Performance and Satisfaction in an Online versus a Face-to-face Introductory Sociology Course.” Teaching Sociology 40 (4): 312-31.

Ellis, R. & Calvo. R. A. 2007. “Minimum Indicators to Quality Assure Blended Learning Supported by Learning Management Systems.” Journal of Educational Technology and Society 10 (2): 60-70.

Fleshner, Nathan. 2014. “There’s an App for That: Music Theory on the iPad, iPhone, and iPod.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 27: 269-80.

Frank, Robert J. & Metz, Ken. 2010. Fundamentals for the Aspiring Musician. New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

Gallien, T., & Oomen-Early, J. 2008. “Personalized Versus Collective Instructor Feedback in the Online Courseroom: Does Type of Feedback Affect Student Satisfaction, Academic Performance and Perceived Connectedness with the Instructor?” International Journal on ELearning 7: 463-76.

Grijalva, T. C. & Associates. 2008. “Academic Honesty and Online Courses.” College Studies Journal 40: 180-85.

Hall, M. 2008. “Predicting Student Performance in Web-based Distance Education Courses Based on Survey Instruments Measuring Personality Traits and Technical Skills.” Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration 11.

Jones, Kona Renee. 2013. “Developing and Implementing a Mandatory Online Student Orientation.” Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 17 (3): 43-45.

Kolb, David A. 1984. Experiential Learning. London: Prentice Hall.

Landrum, R. Eric & Dillinger, Ronna J. 2004. “The Relationship Between Student Performance and Instructor Evaluations Revisited.” Journal of Classroom Interaction 39 (2): 5-9.

Lively, Michael. 2005. “D. A. Kolb’s Theory of Experiential Learning: Implications for the Development of music Theory Instructional Material.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 19: 77-100.

Mandernach, B. J., & Associates. 2009. “The Role of Instructor Interactivity in Promoting Critical Thinking in Online and Face-to-face Classrooms.” Online Journal of Learning and Teaching 5 (1): 49-62.

Mupinga, D. M., & Maughan, G. R. 2008. “Web-based Instruction and Community College Faculty Workload. College Teaching 56 (1): 17-21.

Nash, R. D. 2005. “Course Completion Rates among Distance Learners: Identifying Possible Methods to Improve Retention.” Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration 8.

Orellana, A. 2006. “Class Size and Interaction in Online Courses.” Quarterly Review of Distance Education 7 (3):229-48.

Stevens, Patricia. 2001. “If They Ask You to Put Your Course Online Over the Weekend, Tell Them to Take a Hike.” Proceedings of the World Conference on the WWW and Internet. ED 467072.

Summers, Jessica J. & Associates. 2005. “A Comparison of Student Achievement and Satisfaction in an Online Versus a Traditional Face-to-face Statistics Class.” Innovative Higher Education 29 (3): 233-50.

Urtel, Mark G. 2008. “Assessing Academic Performance Between Traditional and Distance Education Course Formats.” Educational Technology & Society 11 (1): 322-30.

Yu, C., & Brandenburg, T. 2006. “I Would Have Had More Success If...: The Reflections and Tribulations of a First-time Online Instructor.” Journal of Technology Studies 32 (1): 43- 52.

Van de Vord, R., & Pogue, K. 2012. “Teaching Time Investment: Does On-line Really Take More Time than Face-to-face?” International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 13 (3): 132-46.

Williams, P. 2003. “Roles and Competencies for Distance Education Programs in Higher Education Institutions.” American Journal of Distance Education 17: 45-57.

Williams, W. M. & Ceci, S. J. 1997. “How’m I Doing? Problems with Student Ratings of Instructors and Courses.” Change 29 (5): 12-23.