Abstract

An experimental curriculum project was developed to incorporate a music major's understanding of music in the video recording of concerts. The directorial approaches of Kirk Browning (to entertain a general audience), Leonard Bernstein (to educate), and Herbert von Karajan (to produce a new art form) were used as models. Student theorists, conductors, and composers analyzed scores and later directed production crews equipped with multiple cameras. The productions that resulted were designed to lead the viewer's attention to structural elements in the compositions rather than just showing the surface details of a performance.

There is a companion website with links and examples at: http://rkwilley.com/videodirection

Introduction

Musical analysis has traditionally been used to help understand how a work was composed, how it is heard, and how it could be performed. Analysis can also be used as a basis for how the music could be shown. In this experimental curriculum project music students collaborate with video camera operators to produce recordings of departmental performances, and choose camera angles based on the structure of the music. This activity provides a new opportunity for students to apply and develop their understanding of music, and an enhanced experience for viewers by guiding them towards important features in the music, rather than just the surface details of appearance and gesture.

This report is divided into two sections. The first part covers the basics of video direction in order to provide a foundation for understanding the projects we have been developing, followed by a discussion of the work of three sources of inspiration—Kirk Browning, one of the leading directors of concert music videos in the United States; Leonard Bernstein who led 53 of the Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic; and Herbert von Karajan, who was created a production company to document his work with the Berlin Philharmonic. In the second part examples of how college students applied their study of music to video direction and the results are described.

Composing Shots

There are three basic categories of shots in a video recording. Long, “wide” establishing shots give the viewer an impression of the location and the audience in attendance (Figure 1). In a concert video, long shots are typically used at the start and end of the event, and at the beginning and ending of pieces or movements. Medium shots show one or a few performers from head to toe, and provide some detail even when seen on a small screen (Figure 2). Close-ups, or “tight” shots are obtained by zooming in on part of one player, for example their upper body, face, or hands (Figure 3). They are especially effective in television productions, since they provide the viewer with an intimate view that is not available to someone seated in an auditorium.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

If only one camera is used to record a performance and the music isn’t known in advance, the two basic choices available to the operator are to stay on a wide shot so that most or all of the action is always in view, or to zoom in for a close-up to get more detail. Unfortunately, neither approach produces very good results. In a wide shot every performer is in view, but the viewer can’t see clearly who is doing what, or the performers’ expressions. The motion is usually jerky if the inexperienced camera operator tries to pan over to parts of interest, and by the time they arrive the action may have moved elsewhere.

If two or more cameras are used, the footage recorded from different angles can be edited together and synchronized with an audio recording, but this requires more time and effort than what is often available. One way to improve the outcome is to study the music in advance and plan what shots to get. Music students at our school have become involved in the preparation and use their understanding of music to choose the angles and degree of zooming of two or more cameras, and a series of interviews were performed with leading directors and producers in the industry in order to see if there were any guiding principles or theories of how shots should be composed in order to better represent the music.

Three Approaches to Directing Concert Music Videos

Kirk Browning (1921–2008) began his career in television in 1948 directing broadcasts of the NBC Symphony Orchestra led by Arturo Toscanini. He became one of America’s most prolific and versatile directors of televised performing arts, including the direction of 185 programs for the PBS Live From Lincoln Center series. Browning said that there are three approaches a production can take—to entertain, educate, or to present an aesthetic, and that the audience that the program is designed for dictates which one a director should choose. Since his broadcasts were for a general audience, he believed he should to entertain and get the best response from the average listener. His purposes was not try to visualize music or to educate, but rather to show a one-of-a-kind performance that would never be repeated.

Browning said that the audience expects variety and involvement, with the camera taking an active role instead of just being an observer. He went from 150 shots in programs recorded in 1976 to up to 500 to 600 for a two-hour program by the end of his career. For him, the camera was used represent the music in visual terms, interpreting it in addition to supplying information. While he was a pianist and could read a score, he made his choices by listening to recordings and watching rehearsals, choosing shots he thought the viewer would like to see if they could view the performance in detail from a position in the middle of the orchestra, above it, or any of the other positions where he had cameras:

“I use the camera to enable the eye to help the ear hear music better…I’m using the camera as the viewer’s eye. All the choices I make about movement, close-ups, the rhythm of the shots, is an effort to translate what I think the eye would do in a concert hall if it had the opportunity to move… We’re thinking about what we can do so that people won’t get bored and switch off” (Browning, 2004)

The camera work shown in Video Example 1 of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” is not always dictated by the score. There are instruments shown that are not prominent in the audio track, and the audience is shown listening.

(Video Example 1: The Sorcerer's Apprentice, video directed by Kirk Browning.)

The second type of approach according to Browning is intended to educate. This appealed to Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), who appeared in 53 episodes of the Young People’s Concerts over a fourteen year period, covering topics such as jazz and folk music in the concert hall, music theory, orchestration, modern music, individual composers, and the meaning of music (Video Example 2). Bernstein was a natural in front of the camera and an entertaining host, and applied the experience he had as a teacher at the Berkshire Music Center and Brandeis University before becoming Music Director of the New York Philharmonic. He spent his time and energy preparing the scripts and rehearsing the music and trusted the director and crew with the choice of camera angles. In approval screening sessions he was known to suggest showing more of the musicians and less of himself (Hohlfeld, 2016). Bernstein was interested only in the music, and told Browning “as far as I’m concerned the only reason to televise music is to represent what’s in the score” (Browning, 2004). Browning felt that such a literal approach worked for musicians but not for a general audience, who prefer to see a more personal side of an event.

Video Example 2.

The work of Herbert von Karajan (1908–1989), one of the other great conductors of the twentieth century, represents the third approach to directing classical concert music: to present an aesthetic and not the documentation of a live performance. One of the main activities in the last decade of his life was to record the core repertoire that he had conducted over the course of his career on film and laserdisk, and to do so in a series of shots that were carefully planned and recorded in separate takes (Crutchfield, 1993). From the mid-1960s to 1979 his television broadcasts were mostly produced by Unitel, which was founded by Karajan and media mogul Leo Kirch to present classical music in visual media with the highest musical and technical standards. However, he did not like the way that director Hugo Niebeling’s interesting camera angles, soft focus, mirrors, colored floors, overhead shots, and dramatic montages distracted from the music (Video Examples 3 and 4), so in 1979 he formed his own company, Telemondial, in order to have complete artistic control, and became the only major conductor to create film and video productions at his own expense. The members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra were set up in novel arrangements and played sections of each piece along with a pre-recorded track as they were filmed from a variety of angles under special lighting. Karajan had a very clear idea of what the films should look like, and combining backlit close-ups of individual players and sections with larger groups and sequences of himself conducting (Video Example 5).

Video Example 3.

Video Example 4.

Video Example 5.

He worked five hours a day with his editor, Gela Marina Runne in the film editing studios that he built in his homes. Rune said that “It is a monument that he makes. It is interesting for him, because he is making something for eternity.” Like the director of a movie that collaborates with an editor to prune and weave together the scenes of a film, Karajan worked with Runne to guide the viewer’s experience of the music and felt that cutting film was as important as conducting. She said that they decided that “the image must be subordinated” to the music (Vaughan, 1986).

Some have suggested that Karajan was an egomaniac and “control freak”, and suspect that he produced audio and video recordings in order to make money and cultivate his image. Horant Hohlfeld said that Karajan instead made the films to “preserve classical music and the artistic skills of the past” (Wübbolt, 2008). Matthias Röder, managing director of the Karajan Institute believes instead that he undertook the work primarily to share the beauty of classical music with as many people as possible. “For him it was very clear that this could be through the means of technology…He put a lot of his own money into the production. You don’t to that in order to make a lot of money, it’s actually a great way to lose a lot of money” (Röder, 2016).

Those interviewed for this study were asked for suggestions for how music students could use their understanding of music to direct video recordings. Brian Large studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London. After completing doctorates in both music and philosophy from the University of London he joined the BBC2 television as a director working with concert music and opera and has gone on to direct many television performances across Europe and the United States. Large had this advice for how director should apply understanding gained from study of a score to the sequence of shots:

The director should be anonymous… I look at the score as the camera script. When you work with a Mozart symphony it’s he that wrote the script, not you… In visualizing the piece you start with the formal structure. For each piece there is a different combination of factors: the instrumentation, harmony, harmonic progressions, and so on. (Large, 2004).

There is not just one right way to direct a video, and many approaches can be successful. The interviews did not result in many specific techniques or processes that can be passed on to student directors. At times it was difficult for the subjects to articulate how they work, since so much of it is intuitive. They suggested using one’s imagination, and in general to look for the most interesting parts of the performance. Those with musical training were best able to articulate how they reflect the structure of a piece, but in the end may go for entertainment value and what will hold the viewer’s attention. Browning said he wasn’t a good enough musician to reveal the form of a composition as Leonard Bernstein did. He said there is no formula for going from a score to list of shots, only a few devices he knows that work, like going to a wide shot during diminuendos and ritardandos, and cutting to a new angle a little before the beat, since it takes the eye longer to adjust than the ear (Browning, 2004).

Some commented on how a director’s approach could be influenced by the style period in which a piece was composed and its formal structure. Roger Englander (who directed most of Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts) suggested that pieces from the classical period are more suited to television than those of later periods. He used only three shots for a twenty minute production of Bach’s Chaconne in D minor for solo violin–the first from the beginning with its start in minor, a second when the piece moves to a major key, and the third for the conclusion in minor. Whereas Beethoven’s and Mozart’s lines are “clean”, Brahms goes in and out, calling for dissolves, which become tedious (Englander 2004). Karen McLaughlin prefers doing Romantic and contemporary music. For her, Baroque music has a static movement pattern, with less ebb and flow, making it harder to treat imaginatively. For that reason, however, she feels that its simpler structure might be easier for beginners, changing angle upon the arrival of a new section, with a slow camera zoom in or out applied over the length of the shot. Even professionals might use this approach (McLachlan, 2004).

Preparing Students

One might assume that students would intuitively understand how to make video recordings, having watched so many themselves, and that they would have the attention span, dedication, curiosity, and ambition to be active and search out the most interesting parts of the action in a scene. In our experience this was not always the case. Too many times a student would simply set up the equipment, face the camera towards the action, press record, and then watch the proceedings without making any further changes. It was found that a discussion of the basics, feedback from exercises, review of results, and encouragement to be active in the process was necessary for both the prospective directors and camera operators in order to end up with usable footage. Students were invited to watch and analyze productions from a variety of directors for inspiration and style, and decide where along the spectrum they wish to be between entertaining, educating, and creating art. In the second section of the paper that follows, a series of productions using different amounts of preparation and types technology.

A useful class exercise is to give students multiple copies of a classic work of art or snapshots of an ensemble taken during rehearsal, and then ask them to indicate several alternatives for shots by drawing boxes with common screen proportions such as 4:3 (for standard definition televisions) or 16:9 (for HD) over the scenes of groups of people (Figure 4). This gives everyone a chance to consider the options of wide, medium, and tight shots. Students who show themselves to have who have an interest and natural eye for composition may be good candidates to operate the cameras.. Another exercise is to have students draw simple stick figures inside frames to create a storyboard series of shots when planning recordings. Students who have an interest in diagramming or articulating a series of shots and a continuity between them may make good directors.

Figure 4.

Student Productions

Phase One: Multiple cameras, no communication, multi-track audio

The first phase of this study began in the Music Media and Theory departments in the School of Music at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Students in music production classes used three or more cameras to record jazz and popular music concerts with the goal of applying their audio recording skills and making entertaining recordings. Unique events were chosen that would appeal to viewers and challenge the students to capture non-repeatable events with skilled performers. There was no communication system between the camera operators and no advance knowledge of what the program would entail other than the style of music and instrumentation. The camera operators were set at different locations and assigned either zones of the stage to cover or specific musicians to focus on, and instructed to apply their understanding of the general function of each instrument in an ensemble to how they treated them in general, and to watch for times during the concert when they changed between lead and support roles. One camera was set on a wide shot so that there would always be an option to cut to it afterwards while editing in case the other cameras were all moving or refocusing at the same time. An Alesis HD24 recorder was connected to the direct outs from the front of house PA system in order to capture the sound from each microphone on a separate track. After the event the multi-track recording was mixed to stereo, the video tapes from each camera were loaded on the computer, synched with the audio, and edited together using Final Cut Pro (Video Examples 6–15).

|

Video Example 6. |

|

|

Video Example 7. |

|

|

Video Example 8. |

|

|

Video Example 9. |

|

|

Video Example 10. |

|

|

Video Example 11. |

|

|

Video Example 12. |

|

|

Video Example 13. |

|

|

Video Example 14. |

|

|

Video Example 15. |

Even though inexpensive cameras were used, it was satisfying to switch between multiple camera angles and synched with a high-quality stereo audio track as compared with single a single camera recording with the audio it picks up at some distance from the stage. What was missing was communication between the director and camera operators in order to get more usable shots, and to be able to switch between them on the fly in order to end up with a finished recording at the end of an event so that there wasn’t a need to spend so much time to edit the footage together from multiple cameras in postproduction.

Students were generally effective at switching from one camera angle to another based on their experience as musicians and familiarity with popular music-based styles. Video examples of jazz, Cajun, blues, Creole, pop, bluegrass, and world music made during Phase 1 are shown on the companion web site.

Phase Two: Director in Contact With Camera Operators, Live Switching Between Angles

For these recordings a partnership was created between the local cable access television station and the Music Media department. They provided an experienced director, good-quality cameras, and a video switcher. The director gave instructions to the students who operated the cameras and recorded the audio. This resulted in a much higher quality product visually. Eliminating the delay caused in postproduction made it possible to give the performers quicker feedback and to capitalize on the newsworthiness of the events (Video Example 16).

Video Example 16.

Phase Three: Theory Students Direct Studio Recording

At the start of this project we relied on the students’ basic familiarity with popular music, which transferred to jazz, zydeco, and Cajun music. Most of the students had less experience with classical music, and the recordings they made of ensemble concerts in the School of Music did not result in a satisfactory level of detail. It was decided that advance study of the scores was necessary to guide the camera operators to get the shots that would be of interest to musicians, and that making educational videos would give theory students an opportunity to approach their study from a different perspective.

For this phase of the project, sophomores in form and analysis courses did the planning. The simplest way to record is to use one camera and to shoot when there is no audience present so that the technicians can start and stop the recording, move the camera around, and receive instructions without headsets. One of the pieces recorded this way was the piano solo Desperate Measures by Robert Muczynski. The class began by watching recordings previously made using two cameras, one from an audience’s perspective, and a second from above looking down at the keyboard. The composition is in theme and variations form—some are syncopated, one is a tango, and another more dissonant and contemporary sounding. Students were asked to propose an editing plan indicating when they would switch from one angle to another, and then discussed how they arrived at their decisions. Most chose the overhead camera for virtuosic passages in order to show the player’s hands, and then switched to the side camera during the more lyric parts, in order to show facial expressions and body movement. Most students chose to change angles at the beginning of each variation in order to draw attention to the new section. Some occasionally changed angle in the middle of a variation to highlight the repeat of the A or B section, or the break between them.

One approach to making a video such a piece is to treat each variation differently. In one the focus could be on minute finger work, in a another the view switched to the pianist’s elbows and hands. The goal is to marry the visuals with the variations. In the course of the discussion some students said they wished they had more choices than just the overhead and side shots, and talked about other angles that they would prefer for certain sections. They were then invited to plan a new studio recording session of the same piece, and were encouraged to propose other positions for the camera to complement what was different in each variation. The camera remained fixed over the course of each variation in order to make it easier to record, edit, and mix. The class discussed the plans and arrived at a decision for where the camera should be placed for each variation (see slideshow from Desperate Measures). This project got the students thinking about making choices of what to show based on musical imperatives, and prepared them for a larger scale project in which they took a more active role.

Phase Four: Theory Students Plan Live Recording With Director and Headsets

For this project, the same form and analysis students acted as directors, planned the composition of shots, and cued the camera operators during concerts. Music production students made audio and video recordings, which were then mixed and edited and distributed as CDs, DVDs, and posted on the website.

Theory students were divided into groups of three or four, with each assigned one of the pieces to be performed on a large ensemble concert scheduled for the end of the semester. Each student wrote a traditional analysis paper, beginning with a historical context for the composition, an analysis of the piece’s harmony, form, motives, themes, rhythms, main sections, instrumentation, and texture. In addition, each group collaborated on the proposal of a plan for making a video recording using three cameras, including an explanation of how the understanding gained from the analysis papers had been incorporated into the plan for direction of camera angles and composition of shots.

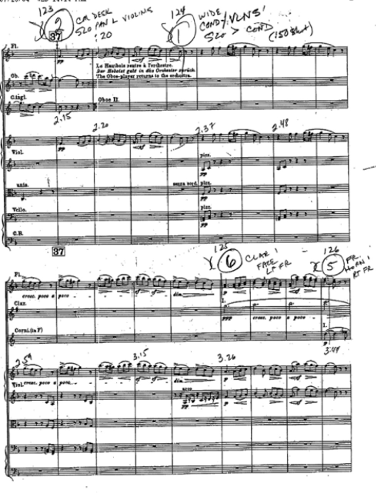

Two types of indications were made in the score, one when the angle should be changed and to what part of the ensemble, and another preceding each of those markings by twenty seconds or so with a cue to the camera operator telling them to prepare for a new angle. During the concert two students from the theory class worked in the auditorium’s booth. One served as the director and was chosen for their good communication skills, and ability to remain calm under pressure. The other acted as score reader, the only requirement for this position was the ability to count bars and keep one’s place in a score. The score reader pointed to the passing bars while the director communicated the instructions written in the score to the camera operators. For example, after one camera operator was told over a headset to continue to focus in one section on the cellos playing the main theme, a second camera operator was warned to prepare for a flute solo coming up in twenty seconds, so that by the time the solo started they had had time to pan to the woodwind section and zoom in on the flutist. If this series of actions was performed correctly the flute solo was neatly captured by the second camera which can be inserted into the recording at the proper time. It is helpful for the crew to have a chance to practice, ideally during a dress rehearsal the day of the performance, so that more detail can be retained in memory.

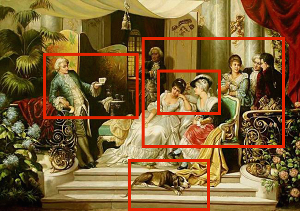

Figure 5 shows an excerpt from a score used for a professional broadcast of Symphonie Fantastique. The cameras are labeled by numbers with circles around them. Dissolves (fading out one shot while the next one fades in) are marked in the script by “)(“, while straight cuts one shot to another are indicated with a “|”. (McLaughlin, 2004). Some aspects in the score are fairly easy to represent visually, such as division points of major sections in binary, ternary, or sonata forms. Other aspects do not lend themselves as easily to translate, such as the development of themes, harmonic structure, and the relationships between small and large elements. Brian Large had these suggestions for musicians interested in finding a visual counterpart to the form of the music:

The list of shots can start out from a literal perspective. For example, you might start with the oboes for three measures, and when the clarinet takes over, you switch to the clarinet. This becomes mechanical, predictable, and boring, but it is the best way for students to begin…In a Beethoven sonata following a ternary ABA design, you can follow the underpinning of the structure. You could begin with an establishing shot on the subject, go off somewhere for the B, and return to the same framing and structure for the final A. (Large, 2004)

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

As both the directors and video camera operators were novices in this project, students were advised to devise simple plans such as concentrating on changing angles at the start of main sections. In a binary or ternary work two or three shots respectively could be used, with the camera zooming in gradually to accompany movement toward a section’s harmonic goal. For a rondo or fugue, an obvious strategy might be to switch to instruments playing the theme each time it returns, and to treat transitions and episodes more freely. For a movement in sonata form a wide establishing shot could be used for the introduction, two shots for the exposition’s main theme groups, a more active treatment of the development, one or two shots for the recapitulation, and a return to the opening wide shot for the coda. Within this framework choices for each shot could be made based on qualities such as the rate of harmonic movement (affecting speed of panning or zoom) and general dynamic level (louder sections seen from further back, softer ones seen close up). Complimenting changes in texture requires more advanced technique, such as changing focus and depth of field, varying the rate of panning and zoom, or overlaying multiple images. While motives may be too short to highlight, the eye has time to adjust to the highlighting of a theme, and camera movement can settle for cadences.

Some students do not always listen to the score examples in textbooks and this project gives them a new reason to do so, and as they spend more time with a work gain from the increased exposure. This activity connects abilities and experiences in other domains such as visual art, communication, drama, and psychology to the understanding and appreciation of music, and offers an opportunity for students with diverse learning styles to take leadership positions. Some students who had not volunteered much in previous classes discussing harmonic rhythm, modulations, and retransitions had the most ideas to contribute about choice of shots and continuity when the discussion shifted to visualizing a work.

Browning encouraged students to go beyond merely focusing on main themes, to find interesting aspects of a piece, and to then use their imaginations in order to visualize them:

It’s terribly important to phrase the process, so that you don’t settle into a lot of close-ups, and a lot of the same moves. To orchestrate it in a way that doesn’t get repetitive, automatic, and predictable. It’s a very personal choice. Some people feel that it’s helpful for the listener when you have a dialogue between two instruments that you go back and forth using the same pair of cameras. I don’t ever do that. If there is that kind of dialogue I try to use different cameras when I go from one instrument to the other. The technique is called “Mickey Mouse”. If you “Mickey Mouse” music you’re representing music in a cartoon fashion” (Browning, 2004).

Another director, Merrill Brockway agreed with Browning that such an obvious approach becomes boring: “It has to be entertaining, not just be accurate reporting. Illuminate the audience. Make them interested in what they’re seeing. Do close-ups on players, you don’t always have to show instruments.” (Brockway, 2004)

One of our most successful productions from this phase of the project was a surround sound, five-camera production of Requiem of Psalms, a choral work commissioned from a local composer, which required an orchestra and the blending of eight choirs.

Video Example 17 is of the sixth movement (“Sing To The Lord”), showing the master shot recorded from the back of the auditorium. This is what the performers would usually get from a single camera operator resorting to a wide shot. No one is left out, but the viewer can’t see much detail.

Video Example 17.

Video Example 18 shows the edited video of the same movement following a plan derived from a theoretical analysis of the work, in which changes in distance, angle, pan, zoom, and opacity of images provide visual variety and views of important details in the piece.

Video Example 18.

Phase 5: Songwriting Students Create Music Videos

In 2013 the work was taken up again at the School of Music at Ball State University, and this time involved students in a songwriting class. One of the recurring goals in the class was to create prosody in songs. The melody in a song with good prosody fits the rhythm and meaning of the lyrics (Pattison, 2011). This idea can be extended to how the song is produced when it is recorded, by having the evolution of the arrangement and instrumentation follow from the lyrics as well. For example, deciding if and when to add supporting layers of instruments and background vocals as the song progresses should follow from the meaning of the song and not just in order to build for dramatic effect.

For the final songwriting project in class the students were asked to asked to extend the idea of prosody between lyrics, melody, and production to a unity with the direction of a music video. One way to do this is to parallel the recurring lyrics in a chorus with the same type of video shot in terms of subjects, location, angle, and degree of focusing, as was done in the song “Tools” by Adam Jefferies (Video Example 19). Another opportunity could be in the bridge section of a song, whose basic purpose is to connect two sections of the song and to provide contrast. Musically the bridge can to this, for example, by moving to a different key, changing the harmonic rhythm, changing the nature of the melody, or switching the lyrics to a new perspective. In the bridge section of a video the scene could likewise change to a different location, time of day, color and lighting scheme, characters, costumes, or rate of change of angles and amount of zoom.

Video Example 19.

Video Examples 20–23 show additional applications.

Video Example 20.

Video Example 21.

Video Example 22.

Video Example 23.

Phase 6: Conducting Students Direct Camera Operator/Switcher

For the latest phase the project was widened to include conducting students to participate as directors. Ball State University’s auditorium is equipped with three remote-controlled cameras operated by a music production student in the recording booth while watching the images from the three cameras on a monitor screen while switching from one angle to another whenever they think a change of angle is called for. The resulting video is combined with what another student is recording and for certain concerts, streamed on the Internet. In the past the student operating the camera controls has not been familiar with the music and changes from one long or medium shot to another as they see fit. While it is desirable to have video recordings of concerts, the results are often disappointing, for example, in a recent recording of Die Fledermaus last semester (Video Example 24)

Video Example 24.

In order to improve the situation for the last concert of the season by the Wind Ensemble and Symphony Band, a call was made for students who might be interested in planning the broadcast based on advance examination of the scores. A conducting student volunteered to act as director, was briefed about the work that had been done in the past to plan shot, and then met with the ensemble directors in order to get copies of the score and discuss what they would like to see in a directed video. He and the student who operated the cameras had a quick practice session before the concert started, and the two seemed to communicate well as they sat side-by-side in the booth, as can be seen in the video taken of two during the concert (Video Example 25).

Video Example 25.

The conducting student who directed the recording primarily composes orchestral music and was fairly new to how bands are set up. “Doing this project helped me get a good sense of how band music is written and where the players are located.” The student who operated the camera reported that “It is easier to make decisions about what to close up on if you know what is coming in the music. It allows shots to be set earlier. I think being present for at least a portion of the dress rehearsal would be beneficial.” She suggested that the student director think more simply and make fewer changes in the future, and to just plan for solos and some section highlights. The conducting student explained his reasons for being so active in the change of angles:

If the music is a dynamic, actively changing piece, the camera changes need to happen more often, otherwise some shots wouldn't make any sense. Take it from an audience member’s perspective, they don’t just look at the entire ensemble all at once the entire time, especially if there is a lot going on in different locations. They look around, and the cameras, in my opinion, need to imitate this movement. This may call for the operator to be more busy, but that’s what they’re being paid to do: to emulate the show that an audience member is seeing live. That is just my opinion on the matter. Anyway, I appreciate the experience and I thank you for giving me the opportunity to learn something new!

Conclusion

Students generally enjoyed the assignments. Knowing that their work would be seen by their peers and publicly displayed increased their desire to do quality work.

This activity puts students in a position to look at music theory from a different perspective. Some who do not participate much in class became more active as their abilities in other areas were engaged, such as interpersonal communication and visual imagination, and new leaders emerged. Teams doing group work in class appeared more engaged by the novelty of the assignment while planning their shooting scripts, compared with times they are analyzing a score’s form or harmony in a traditional assignment.

Students grew under the pressure of producing non-repeatable events. Rehearsal and performance schedules created deadlines and a sense of urgency which traditional theory assignments don’t have.

Roger Englander, when asked for suggestions on how to make the work as meaningful as possible for students replied, “It is stimulating. Push them. Get them to understand the problems they will need to solve. It opens up something broader in the study of music.” (Englander, 2004). Those who analyzed the scores, attended rehearsals, and planned the video production had more invested in the concert, and consequently had deeper reactions to the performance. After completing the work students seemed to have more sensitivity to the expression and body language of the conductors they studied, and were more aware of their style in published recordings seen in class.

Video direction informed by a study of music may result in more enjoyable and educational presentations. A combination of wide, medium, and tight shots structured in well-timed sequences, and with a balance between predictability and surprise can hold a viewer’s attention longer and increase their enjoyment. Alternating shots from two or more cameras provides a variety of perspectives and intimacy that is not available from a seat in the auditorium.

The finished productions provide quality feedback for performers, better documentary artifacts for the department, and educational and entertaining material for the public, especially for those unfamiliar with classical music and the concert experience (Video Example 26). Recognizing the structure of music is an important part of appreciating it. Timing camera angle changes to direct the viewer to important features can help the viewers better understand what is going on in a complex multi-layered composition.

Video Example 26.

Future Directions

We plan to involve a wider range of students in this activity. This project began with theory students, and later added songwriters and conductors. Next we would like to include performance and music education majors, as well as film students from the Telecommunications department, and look forward to seeing differences in styles. Projects directed by theory/composition students may show more attention to delineating structural elements, themes, and their development. Conducting students may plan their shots the same way they think of cueing the entrances of sections in the ensemble. Performers may want to see the expression and interpretation of their colleagues and highlight virtuosic passages. Music education students may choose to explore the possibilities to use the activity in their own teaching, or to produce instructional materials. Non-music-major documentary videographers may show more of performers onstage who are not playing the main themes, as well as the audience’s reactions.

It is possible that next year a theory elective class will be offered for students interested in covering a series of concerts. The ensemble directors who have been approached have welcomed the possibility of getting more detailed recordings of their groups and have been pleased with the results so far: “I thought the production was much better than in the past. It was more logical. I believe people would like to see what they hear.”

Quantitative analysis could be done to look for patterns in the common practice of professional directors. Those that were interviewed for this study were not able to articulate how they went from score to a list of shots, but perhaps trends could be teased out from collected data. For example, it may be that more wide shots are used to mark arrival points, and that the rate of edits generally increases during turbulent development sections. Multiple recordings of the same work could be put side by side, as was done to compare different versions of a film edited by Niebeling and Karajan of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Karajan felt he was born too early too early for the technology to be developed to express his vision. The cost of video switchers has dropped and there are now even apps for phones and tablets that connect them to make it easy to produce multi-source content with devices students and faculty already own.

We are on the cusp of a change in the way recordings are made and viewed. At the time of this writing, 3D and virtual reality systems are about to be introduced to the marketplace. These systems will allow viewers to decide where they want to look instead of relying on a director to make the choice what to show them. Larger displays with greater resolution will reduce the need for a future Kirk Browning to feel the necessity to use the camera as the viewer’s eye, since they will have enough detail in a wide shot for the viewer to be able to choose on what part of the stage to focus their attention, as they would if they were present for the performance. However, there will probably always be a market for a director to prepare what to show an audience and to refine what has been recorded in postproduction.

Henning Kasten, who incorporates sweeping jib shots in recordings of live concerts, said that one possible future development in recording concert music will be the smooth, continuous one-shot approach he took in “A Flight Through the Orchestra” (Video Example 27) in which “the sound changes according to the position of the camera. An instrument closer to the viewer sounds more immediate and louder than instruments further away, creating an experience of being fully immersed within the orchestra.” (Kasten, 2016). The planning of the path the camera for this approach is different than for a production made by cutting between a series of shots from multiple cameras. The smooth movement holds the viewer’s attention and guides them in a continuous motion like one’s eyes normally move across a scene. This experience could be offered to viewers, along with a the choice of switching to one of a number of stationary cameras that record in 360 degrees, allowing one to turn their head to look at what interests them.

Video Example 27.

Founded in 2008, the Digital Concert Hall of the Berliner Philharmoniker has been extending Karajan’s legacy, and offers more than forty live broadcasts in high definition video each season to movie theaters in Europe and subscriber’s devices via the Internet. A subscription to their service includes access to more than 800 archived concerts, including Karajan’s work from the Unitel days. Today’s video technology allows for high quality live recordings that were not possible even in the studio in Karajan’s time. In the future orchestras may decide to put more effort into producing programming for a large networked audience.

Experience gained with directing concert music video could inform the production of other types of besides recording performances. Examples of experiments done with 3D animation of MIDI sequences and during Phase 4 of this study at the Louisiana Immersive Technologies Enterprise and Max/MSP shown in Video Examples 28–31 and Figures 6–7. Audio players like iTunes and Winamp display images that respond to changes in pitch, timbre, and rhythm, but more could be done to help visualize music’s form. Visualization of music, as was done in Walt Disney’s Fantasia can help engage audiences unfamiliar with sophisticated classical music. We are talking with animation faculty about collaborations between our departments, and have begun presenting concerts in the university’s old planetarium, which has been turned over to the IDIA lab for its virtual reality research (Video Example 32). We are looking forward to involve students and faculty in exploring the possibilities that such new technologies will offer (Video Examples 33–34).

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Video Example 28.

Video Example 29.

Video Example 30.

Video Example 31.

Video Example 32.

Video Example 33.

Video Example 34.

Bibliography

McLaughlin, Karen. Video score notations for Symphony Fantastique. Personal communication to author.

Bernstein, Leonard. Scripts for the Young People’s Concerts. Leonard Bernstein. May 20, 2016.

Brockway, Merrill. Interview by Author, August 3, 2004.

Browning, Kirk, interview by Robert Willey, June 23, 2004.

Crutchfield, Will. “Video View: Karajan Faces Stiff Competition: Karajan.” The New York Times, July 18, 1993. Web. May 30, 2016.

Englander, Roger. Interview by Author, 3 August, 2004.

Erben, Susan. Interview by Author, 10 August, 2004.

Finnäs, Leif. “Presenting music live, audio-visually or aurally—does it affect listeners’ experiences differently?” British Journal of Music Education, 18:1, 55-78.

Forney, Kristine. The Norton Scores, eighth edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Ltd., 1999.

Hevesi, Dennis. "Kirk Browning, 86, Dies; Put the Arts on TV", New York Times, Feb. 13, 2008, Web. May 25, 2016.

Hohlfeld, Horand. “Re: Video direction as an application of the study of music theory.” Email to the author. May 24, 2016.

Kasten, Henning. “Re: Information on Herbert von Karajan.” Email to the author. May 2, 2016.

Kasten, Henning. “A Flight Through the Orchestra.” Deutsches Symphonie-Orchestra, Berlin, conducted by Tugan Sokhiev. Euroarts, 2015.

Large, Brian. Interview by Author, September 1, 2004.

McLaughlin, Karen. Interview by Author, July 3, 2004.

Pattison, Pat. “Prosody.” The U.S.A. Songwriting Competition, May 5, 2011. Web. 6 May 6, 2016.

Rose, Brian. Televising the Performing Arts: Interviews with Merrill Brockway, KirkBrowning, and Roger Englander. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1992.

Schroeppel, Tom. The Bare Bones Camera Course for Film and Audio, Coral Gables: Schroeppel, 1980.

Vaughan, Roger. Herbert von Karajan: A Biographical Portrait. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1986.

Warivonchik, Vicki. Interview by Author, August 10, 2004.

Röder, Matthias. Interview by Author, May 18, 2016.

Willey, George. “The Visualization of Music on Television With Emphasis on The Standard Hour.” Ph.D. diss. Stanford University, 1956.