Introduction

In recent years, the debate over the use of laptops in the classroom has become more vocal due to the affordability of technology, the widespread availability of Wi-Fi throughout most universities, and the students’ expectations that those services are available to them in the classroom (Schaffhauser, 2008). While some professors strictly forbid the use of laptops and tablets in their classrooms, others have decided to allow students to use technology, but with mixed results. Some studies indicate an improvement of student performance when the use of laptops is encouraged during the course of the semester (Weaver & Nilson, 2005; Samson, 2010). In a study involving undergraduate students in social sciences, Granberg and Witte (2005) show that laptop use in the classroom can be helpful, and that the inclusion of laptops can enhance both students’ academic progress as well as intellectual development. Yet, other authors report a decrease or no difference in student performance and engagement (Sana, Weston, & Cepeda, 2012). In a study using two separate course sections of an undergraduate course in general psychology, the outcomes of laptop usage were deemed negative (Fried, 2006). Fried argued the laptop usage had a wasteful effect on the students’ time and a negative effect on their overall progress. He indicated the laptops were used for other tasks than note taking during the lectures. This topic has also gained the attention of national news media, and numerous news and research articles have addressed the issue with opinions ranging from pro-technology (Gurgel, 2013; Samson, 2010; Sharp, 2013) to strict bias against (Glass, 2012; Young, 2006; Snyder, 2010). Yet, while the criticism might be correct, it is centered on whether laptop usage is beneficial to students, and fails to address how laptop usage can be beneficial to students. Over the last few decades, educational technology has allowed professors to base their lectures in a presentational format, such as Powerpoint or Prezi. These formats have eased the way that students can take notes, yet might have lessened the interaction between professor and students at times. Adding laptops to that mix might have further decreased the interaction between professor and students. As Holstead (2015) noted, many professors might have created classrooms where students are hardly taking notice of the professor and instead occupy themselves with copying notes from the Powerpoint presentation straight onto their laptops.

Consequently, the purpose of this study came from one of the authors who believed that how he had incorporated the use of laptops was beneficial to his students, while the other author was very cynical towards the usage of laptops and often prohibited students from using them in the classroom. It led the authors to the development of a two-stage study design. For the first stage, the first author set up a quasi-experimental study that allowed him to compare the students that used a laptop in his class with those students that did not. When the results of that study confirmed the beliefs of the first author, the second author then conducted a qualitative study, consisting of interviews, observations, and teaching evaluations to triangulate the quantitative data of the first author and better understand the reasons for the results.

Literature review

The challenges and benefits of using laptops in the classroom

The current study in the live entertainment management classroom was inspired by the growing amount of literature on the topic of the use of technology in teaching. While the literature on classroom teaching and the use of laptops is limited, there is growing attention being given to the subject. The general consensus on classroom laptop use in regards to research available is somewhat evenly split with evidence suggesting both pros and cons in regard to student progress and academic achievement.

Previous research demonstrated that the integration of meaningful laptop activities is important for digital natives--the term used for persons who were born after the general implementation of digital technology and who have familiarity with it (Samson, 2010). For integration purposes, Samson used deliberate engagement via software called LectureTools. The subjects in the study were undergraduate students in a large introductory science class, where the instructor was “challenged to support a wide and diverse range of student learners.” Approximately 75% of the students had laptops, illustrating the possibility of them participating in a web-based option of the course. They were surveyed at the beginning and end of the semester, as well as during random survey days, regarding their attitudes about science and technology. The response rates for the surveys ranged from 65% to 96% and the rate of students engaging in class discussions via LectureTools software increased exponentially compared to the non-LectureTools semester. The outcome of the research suggests that the attentiveness of the students was somewhat improved as the laptops were specifically integrated and used during the course and lectures. According to Samson, over 90% of the students preferred the use of laptops via LectureTools due to the feeling of being interactive and more attentive.

Kay and Lauricella (2011) found that the presence of laptops raised both benefits and challenges. First, the distraction caused by students' laptop use is a problem for other students, as their eyes are drawn to the screen, instead of the instructor. However, their survey of 177 undergraduate university students regarding their use of laptops in the classroom revealed that twice as many students commented on the benefits of laptops, rather than the challenges it presented. Common benefits were note taking, academic activities, and organization of their work along with communicating with other students, while challenges were mainly distractions such as seeing the screens of other students’ laptops as well as having Internet access, enabling them to easily browse online. It is interesting to note that the survey results showed that instant messaging was reported both as a benefit as well as a common challenge in regard to student engagement and distraction.

An additional study surveying a large undergraduate class of 141 students in a computer science course suggested that the use of laptops was polarizing the students, essentially splitting them into two groups (Barkhuus, 2005), with the laptops either assisting them in following the class or engaging in tasks unrelated to the class. The study used software called ActiveClass that was installed on the student laptops in order to gather data and measure their browsing and note taking habits. ActiveClass software is a web-based lecture engagement method of soliciting student input via their laptops or other portable electronic devices. The software is “built around three primary functions – questions, polls, and ratings.” It allows the students to vote on questions asked anonymously by their peers that they feel most require an answer. It also allows the students to rate the speed of the lecture as “too slow”, “just about right” or “too fast”, along with a numerical rating ranging from one to six. The survey found that despite the anonymous nature of ActiveClass, the shy students remained shy online as well, while those who were eager in class were also active online. Further findings in the study concluded that those students who used the laptop for purposes other than engaging in the course were less receptive to ActiveClass, responding that the software “did not do much for the class.” According to the survey, the student responses indicated that “laptops in-class are used for very polarized tasks: either to assist the student to follow the class, or to engage in a task unrelated to the class.” Research completed by two sociology professors (Granberg & Witte, 2005) showed that laptop use in the classroom can be helpful, and that the inclusion of laptops can enhance students’ academic progress as well as intellectual development.

Managing the laptops in the classroom

Collectively, the aforementioned studies seem to indicate that laptop usage in the class in itself is not necessarily a negative or positive, but that the usage of the laptops need to be managed correctly, in order to make a positive effect. Several studies have highlighted the positive outcomes when deliberate engagement was used via software to keep the students attentive to the lectures. Granberg and Witte (2005) implemented many different measures, specifically to integrate the laptop into the classroom, ranging from designated “laptop days” where students would complete a graded in-class assignment related to recent lecture material, to the every-day use of laptops with integrated assignments on Blackboard and the use of the Internet as a real-time research supplement along with the encouragement to “silently” communicate with their peers during class. One of the challenges directly tied to their study is uncertainty over whether these positive outcomes are associated with their field of study (i.e. engineering or business) due to the need for students to master a specific set of problems that are commonly adopted and used in software programs such as Excel, with the less pressing need of having, as well as using, laptops in the social sciences classrooms, where the focus might be less on skill development, and more on critical reflection and debate. Thus, the purpose of this research is to replicate the study of Granberg and Witte (2005) in a social science setting, using similar methods for laptop usage integration as these authors. For this reason, we developed one hypothesis and one open-ended research question:

H1: There is no significant difference in performance between students that do bring a laptop to class, and students that do not bring a laptop to class.

R1: What can instructors do to implement the use of laptops in the class, without negatively affecting their performance?

Methods

Stage 1: The quasi-experimental study

Research design

To understand how the use of a laptop benefited or hindered the students, we obtained IRB approval and conducted a quasi-experimental study called the non-equivalent control post-test only (NEGD). NEGD’s are structured as a pretest-posttest experiment, but lack random assignment of participants, and they do not calculate a pre-test score, instead they focus on mean score differences between groups (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham. 2005). In our study, we conducted the experiment over a period of three years, spread out over five cohorts. The class that served as the research setting was a 200-level, three-credit introductory course to live entertainment management taught by the first author. This course was required for any student wanting to major or minor in sport and entertainment management. During the first day of class, students were given the choice to use a laptop or not. This violated the random requirement for a true experimental study, yet we believed that not giving them this choice would demotivate the student and worsen his or her performance. The students who chose to use a laptop were required to bring their laptop with them each class period and use it during lectures. Those students who chose to sign up for laptop permission were instructed to sit among other laptop students in the lecture-style classroom, creating a “laptop section” so as not to distract the other students who chose not to use a laptop. This is especially important as current research suggests that, based on classrooms with laptops, non-laptop using students are being heavily distracted by their peers’ use of laptops (Kay & Lauricella, 2011).

Sample

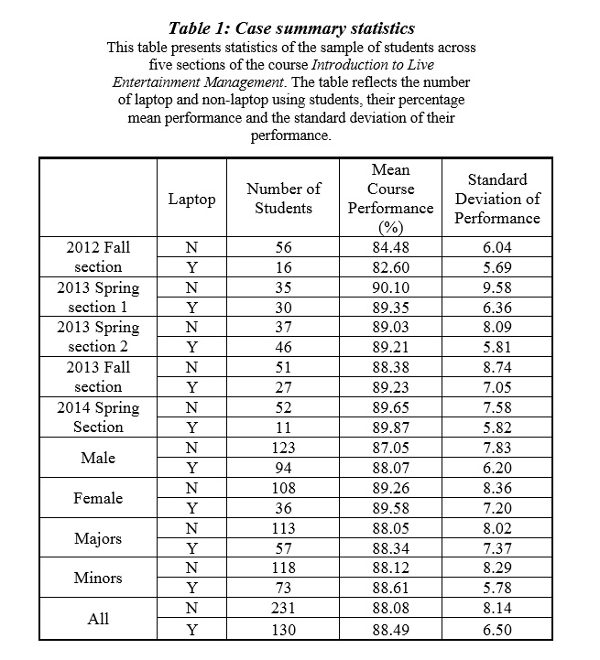

Over three years 361 students participated in this course. Of those 361 students, 130 students used a laptop in class, while 231 students did not. 60% of the students were male, which is slightly higher than the university-wide gender representation, yet this slight discrepancy is unlikely to affect the results of the study. Nevertheless, to control for this demographic, we did incorporate gender as a covariate in the study. Of the male students, 43% of them used a laptop in the classroom, while only 25% of the female students used a laptop. We also controlled for the academic background of the student by asking them if they were a major or non-major in the program. The thought process behind this was that majors might be more passionate towards the subject (surpassing a general interest), and they might have a stronger background in the content area than non-majors. Please see Table 1 for a full overview of the participants.

Measurement

Their final grade was used as the post-test indicator for their performance in the classroom. Because of this, we did not collect a pre-test score, and were dependent on the post-test mean comparison between the experimental group and the control group for validation. Because of existing literature on this subject we had no reason to assume any self-selection bias and we did not fear that one group was representative of a superior group of students. To test whether the mean scores were significantly different, we conducted an ANCOVA test to compare the means between the two main groups, while controlling for gender and major (divided in majors and non-majors) (Hair et al., 2005).

Stage 2: The Qualitative study

Research design

To gain a better understanding of the methods the first author used to encourage correct usage of laptops and discourage incorrect usage, the second author then conducted a qualitative study that consisted of multiple methods. In order to gain an objective view on the teaching methods of the first author, the second author conducted an observational study, an interview with the first author, and a focus group with the students (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The observational study was conducted first, during which the second author attended several classes of the first author unannounced. The approach to the observational study was an open-ended, unobtrusive narrative format (Rossman & Rallis, 1998). Based on this data, the second author developed focus group questions and obtained an additional IRB approval in order to conduct the focus group. An announcement was made in class inviting students to participate in the focus group. The focus group was held during class time and students did not receive extra credit to participate. While this focus group might still have an overrepresentation of students who feel strongly about the class (either negatively or positively), it was our hope that this approach allowed us to minimize biases, and did not have an overrepresentation in one direction. The focus group contained eight students, three females and five males. When asked about their performance in the class and their expected grade, 3 of them indicated they expected to receive a “B”, and the other five expected an “A”. The focus group was semi-structured and contained questions about the performance of the professor (i.e. Do you like the professor?), his teaching methods (i.e. the lack of PowerPoint presentations, the constant dialogue with students, etc.), his approval of laptop usage, and lastly the overall benefit of his lectures towards the exams, so we could control for the fact that ultimately, the lectures might not have mattered. The goal was to better understand the experiences of the students in the classroom (Kvale & Brinkman, 2009). Finally, the second author conducted an interview with the first author, in which he/she challenged the first author in the interpretation of the results. Similar to the focus group, this interview was semi-structured and meant to gain a better understanding of the experiences of the first author/instructor of the course (Kvale & Brinkman, 2009)

Measurement

To analyze the observational data, the second author used his field notes to develop an open coding procedure to analyze the experiences of both the students and the instructor (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). A similar approach was used for the transcription of the focus groups and the interview. Based on these codes, the second author then created themes, which were presented to the first author for discussion (Spiggle, 1994). For validity purposes we implemented strategies proposed by Miles and Huberman (1994). In between the different qualitative methods, the field notes were used to inform the next step of data collection. Additionally, we triangulated the data by comparing the observational field notes, with the transcriptions of the focus group and interviews to search for discrepancies. Where discrepancies were found, a theme was challenged and we proposed a new theme (Maxwell, 2005).

Results

Stage 1: The quasi-experimental study

While the students who used laptops scored slightly higher in this course (88.49 to 88.08), our ANCOVA did not find significant support for a true difference between the two groups, (F: 2.035, Sig: .109) thereby supporting the hypothesis that instructors are able to incorporate laptop usage into the classroom without negatively affecting the performance of the students, even if the instructors are uncomfortable with software programs such as ActiveShare and LectureTools. Neither gender or study discipline (major, non-major) was significant, and we controlled for any gender differences or presumed passion for the subject. The results supported the beliefs of the first author, and allowed for the subsequent qualitative analysis of the second author.

Stage 2: The Qualitative study

As the results of Stage 1 confirmed the beliefs of the first author that laptop use did not negatively affect the performance of the students, our focus for the second stage of the study was to understand why this occurred. To that end, we first focused on the strategies that both the students and the instructor agreed were important, and were supported by the observations of the second author.

Strategies to prevent a negative impact of the laptop

First, it is important to note that the instructor decided to separate the laptop students from the non-laptop students, so that the latter would not be distracted by the usage of the first group. That might have played a positive role, although none of the students commented on it. Yet, the second author did notice that there was very little sideways glancing among students, which would indicate that the forced separation prevented this problem from occurring.

Perhaps, the most important strategy of the instructor to integrate the laptop in the classroom correctly was to avoid the use of PowerPoint slides during the lectures. Instead, the instructor relied on verbal communication, sometimes supported by a key term written on the white board, and tried to have an ongoing discussion with the students, despite the large class size. As one student put it:

I learn better from discussion style, I’m not a big fan of lecture style and sitting in a seat and listening to someone talk for an hour and trying to retain all that information just does not work for me. So the idea of being able to interact with the professor, and being able to ask questions and have the professor appreciate the questions you're asking him because he knows that you’re trying to learn more about the subject, and he does his best to answer your question is a big plus (female student #3).

Observations indicated that not providing PowerPoint slides forced students to more actively take notes, and prevented them from copying any information that might have been given on the PowerPoint slides. Additionally, the instructor continually sought responses from the students, despite the large class size, and would sometimes call on students unsolicited. This again, seemed to force students to pay attention to the instructor; because they worried he might ask them a question. Yet, he was able to do it in a way that students were comfortable with it. As one student put it:

…but I think it’s more calling on than calling out. I think he does a lot more of calling on people in class instead of calling them out because they’re not doing something right or they are not paying attention. I like the fact that he calls on students, because I think he values their input (male student #2).

To help with this process of interaction, the instructor required the students to have a placard in front of them with their name on it in black marker, so he could address the students by name. When students were asked in the focus groups if these made them feel uncomfortable, one of the students stated that they “understood that the instructor was doing this to keep them engaged” (female student #1), and that ”he never directed any hard or complicated questions to the students that might have made them look bad” (male student #5).

The instructor also arrived early to the classroom and played music over the speakers to create background noise, so there were no uncomfortable silences before class started. The instructor did this because he believed: “it loosens up the students and gets them in a mindset where they are more likely to speak up.” Again, the students in the focus group mentioned they liked the music before class as it was seen as creating a positive atmosphere, and the observations of the second author further supported this.

Realistic expectations towards laptop usage

None of the above recommendations should be regarded as a cure to solving student distraction or disengagement. These strategies do not mean that the interaction of the students was much higher than what the observer had experienced in his own classes, or in other people’s classes. The observations showed that it was often the same students who spoke up, and the instructor only called on students once or twice during a class period. The observer noticed several students on their laptops doing activities unrelated to the classroom, yet they were not the only ones. Students without laptops or phones were scribbling, drawing, or seemed to be daydreaming, signaling that a laptop is not a cure, nor a threat to keeping students engaged in the classroom. Yet, what was clear is that the methods that the instructor had developed minimized the differences between those students that prefer to have their laptops available to them and those who prefer not to.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand how and if laptops could be integrated into the classroom, without negatively affecting the performance of the students. Results supported the fact that the methods employed by the instructor did indeed allow for the use of laptops in the classroom, without negatively affecting the performance of those students. While we do not negate the fact that a laptop can be a source of distraction, it seems that blaming the laptop for distracting students in the classroom is an oversimplified solution to a larger problem. It might be that the causality between laptop usage and distraction is reverse, and that boredom with the lecture might be a cause of laptop usage, rather than the other way around.

An analysis of the evidence presented by prior authors demonstrated a relatively equal split on both sides of the “laptops as learning enhancement/distraction” debate. Many studies posit that laptop use is a very effective means of keeping students engaged and enhancing the learning process (Granberg & Witte, 2005; Kay & Lauricella, 2011), while an almost equal number of studies find laptops to be a source of distraction that leads to reduced classroom performance for the laptop users and their neighbors (Barkhuus, 2015). Perhaps the most relevant finding is the one that is underpinned by the outcome of this very study, that is, that the effects of classroom laptop use depends largely on the engagement factor of the professor. An instructor who simply allows laptops in his/her classroom and makes no attempt to engage the students through virtual means as part of the learning experience will likely show decreased performance by the students in his/her class. However, professors who utilize technology in their classrooms for learning purposes through the use of polls, in-class research, lecture contributions, quizzes and various other methods of keeping students involved, reported increased student engagement and performance almost across the board. Porter & Donthu, (2006) discuss age as a strong negative predictor of technology acceptance, which means that most instructors are less likely to adapt to new technology at the same speed as their students. Thus, universities are well advised to provide support for their instructors that allow them to keep up with the progress in this field. Software programs such as ActiveClass and LectureTools are useful programs that allow instructors to incorporate laptops in the classroom (Barkhuus, 2005; Samson, 2010), yet our study shows that instructors also have non-technological tools at their disposal to neutralize the negative effects of incorporating laptops in the classroom, grounded either in classic pedagogic techniques, such as the Socratic method, or by removing one-directional technology, such as PowerPoint and Prezi from the classroom.

We propose that the determining factor that tips the scale in favor of classroom success of laptops is the instructor. Professors who choose to allow passive laptop use in their classrooms will likely see a continuing downward trend in their students’ performance, which will negatively reinforce a pre-existing bias against laptops. However, by making the learning process one in which technology serves a valid learning purpose, students will inherently be more engaged. This study bears out the findings that laptop use in the classroom does not negatively impact student performance, so long as the teacher takes purposeful action to make the technology a vital part of the learning process.

References

Barkhuus, L. (2005). Bring Your Own Laptop Unless You Want to Follow the Lecture": the Case of Wired Technology in the Classroom. GROUP '05 Proceedings of the 2005 international ACM SIGGROUP conference on Supporting group work, 140-143.

Fried, C. B., (2006). In-class laptop use and its effects on student learning. Computers and Education, 906-914.

Glass, N. (2012, September 08). Laptops may be the ultimate classroom distraction. Retrieved from USA Today.

Granberg, E., & Witte, J. (2005). Teaching with Laptops for the First Time: Lessons from a Social Science Classroom. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 101, 51-59.

Gurgel, B. (2013, February 22). Retrieved from Ten reasons the iPad is an awesome tool for classrooms and education.

Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry Babin, Rolph E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham (2005), Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Holstead, J. (Dec 2015) The impact of slide-construction in PowerPoint: Student performance and preferences in an upper-level human development course. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, Vol 1(4).

Kay, R. H., & Lauricella, S. (2011). Exploring the Benefits and Challenges of Using Laptop Computers in Higher Education Classrooms: A Formative Analysis. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 1, 1-19.

Kvale, S., & Brinkman, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Maxwell, J.A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications, Inc.

Miles, M.B., & Huberman, A.M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications, Inc.

Porter, C. E., & Donthu, N. (2006). Using the technology acceptance model to explain how attitudes determine Internet usage: The role of perceived access barriers and demographics. Journal of business research, 59(9), 999-1007.

Rossman, G.B., & Rallis, S.E. (1998). Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications, Inc.

Samson, P. (2010, May 21). How Laptops Can Enhance Learning in College Classrooms. Retrieved from ScienceDaily.

Sana, F., Weston, T., & Cepeda, N. J., (March 2013). Laptop multitasking hinders classroom learning for both users and nearby peers. Computers & Education. 62.

Schaffhauser, D. (2008). College Students Find Wi-Fi Essential to Education, Survey Reports. Campus Technology.

Sharp, D. (2013, March 17). Hawaii joins laptops-in-schools talks. Retrieved from the Honolulu Star Advertiser.

Snyder, T. (2010, October 07). Why laptops in class are distracting America's future workforce. Retrieved from The Christian Science Monitor.

Spiggle, S., (1994, Dec 1). Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data in Consumer Research, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 21, (3).

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1998, Sep 22). Basics of Qualitative Research : Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications, Inc.

Weaver, B. E., & Nilson, L. B., (Spring 2005). Laptops in Class: What Are They Good For? What Can You Do with Them? New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 101, 24-31.

Young, J.R. (2006). The fight for classroom attention: professor vs. laptop. Retrieved from the Chronicle of Higher Education, 2, A27-A29.