Abstract

This paper details a practice-led, reflective study rearranging a studio jazz trio recording into a new, hybrid-ensemble piece with sample-based instruments and sound libraries. How do digital audio workstations affect the creative and technical decisions of a live trio recording? How might a listener perceive these changes? What roles do the sound engineer and arranger have in creative decision-making? The study investigated how using contemporary recording software changed the perceived timbre of an unreleased jazz trio recording from 2007 through technology-mediated production and thoughtful arranging. Results of the study suggest that by employing a modest and conservative approach, virtual instruments can support the timbral qualities of an existing jazz recording, provided they remain unobtrusive. The paper considers issues of realism, authenticity, and professional best practices concerning scoring and mixing. Finally, the author explores the philosophical implications of technology-based composition and arranging on creative music making from the production and engineering perspectives, and how these issues affect music industry and technology related coursework.

Introduction

This article examines a reflective case study involving the creation of a new accompaniment part for an unreleased jazz trio recording called “Sanctuary”. Nearly five years passed between the original session and the new creation—a composite of the original recording and new software-based virtual instruments in a digital audio workstation (DAW).

Recording studios and music production software affect jazz performance and composition. Similarly, how a composer uses software-based sample libraries to create a sense of realism remains subjective, largely determined by the intended use of the underscore. Is the music intended to enhance a visual image? Will the score be professionally synched to a film or a game? How do these issues play out in commercial music and higher education settings? By drawing on writings by Berliner (1994), Born (2005), Eno (2004), Frith and Zagorski-Thomas (2012) and Monson (1996), the perceived influence of recording spaces and technology on creative praxis and the aural experience becomes clearer. Drawing from existing musicology-related scholarship on record production and music technology enables researchers to draw conclusions about how the “studio” influences creativity and pedagogy.

Semi-structured and emailed interviews conducted with the sound engineer between September 2014 and July 2015 offer insights concerning the original recording space. The technical summary is covered in detail in the Recording Information and Production Analysis section. The Discussion section contextualizes the project’s technology-centered production approaches, ethical considerations, and offers further interview analyses and study limitations. Although the context presented here takes place in a jazz setting, the concepts remain applicable to all styles of contemporary music. Additionally, the concepts outlined throughout aim to be helpful regardless of stylistic preferences and specific instrumentation.

Conceiving technology-mediated accompaniment parts for “Sanctuary” not only fulfilled a practical need (in this case creating underscore music)—it also brought up the practical issues of using modern technology to resurrect an unreleased jazz trio recording. The following three research questions became apparent:

- RQ1: Would the timbral experience of this jazz recording change by adding virtual instruments?

- RQ2: Following established scoring, arranging, and mixing procedures, how might the new MIDI-based accompaniment change the listener’s experience?

- RQ3: Once completed, how would the new hybrid piece change the producer and sound engineer’s perceptions of improvised music’s creative process in the recording studio and beyond?

Before addressing these issues, let us explore an overview of the studio and its role in affecting jazz improvisation and composition.

Considering Studio-Mediated Jazz Improvisation

Over the past century, jazz musicians have explored the recording studio’s available tools for creative and experimental purposes. Recording spaces, once frayed environments with little acoustic treatment, now function as professionally treated rooms (Schmidt Horning, 2012). Brock-Nannestad (2012) investigates professional and amateur recording technology over a thirty-year period beginning in the early 1920s, asserting that before commercially available tape machines rose in the early 1950s, amateur and professional recording efforts yielded similar results. These advances in technology encouraged solo artists and groups to capture sound in novel ways. It seems little difference existed between expert and novice recordings.

Les Paul and Bill Evans used overdubbing to enhance their solo compositions. Jago (2013) explains that Sidney Bechet and Lennie Tristano’s seminal investigations layering individual parts and varying tape speed were equal parts revolutionary and shocking for audiences to comprehend in the 1940s and 1950s. Noting that stylistic deviations were unorthodox seventy years ago, Jago (2013) queries how such progressive recording methods alter the modern jazz album’s perception. The collective interaction between the jazz soloist and the rhythm section is a vital component in determining the subjective quality of a musical performance (Monson, 1996).

Interactive rhythm sections propel live performances and studio recordings across musical styles. For example, an engineer documents the moments that bassists and drummers propel a saxophone soloist while maintaining a driving beat. Producers frequently assemble portions of recorded takes to build a composite solo. Nevertheless, using MIDI virtual instruments to create a new accompaniment presents new sonic issues. In contemporary scoring for visual media, composers often grapple with making the most out of their sample libraries. If the budget for live musicians is nonexistent, then these issues become more pronounced in styles that call for swinging rhythms and the like.

An instrumentalist playing along with and responding to their musical vocabulary presents a series of exciting possibilities and complexities (Berliner, 1994). Once tape-based editing enabled sound engineers to splice multiple takes together, musicians doubled their parts, removed unwanted elements, and added increasingly dense musical ideas often unplayable in a live setting (Berliner, 1994). Lennie Tristano’s studio multi-tracking excursions, capable of documenting polyrhythmic and polyphonic textures, changing beats and extended harmonies, deviated too much from traditional jazz performance standards (Jago, 2013). Technology allows musicians and composers to create pieces from an amalgam of different takes. Beyond these stacked ideas, arrangements take on new sonic identities because of the boundless opportunities to layer parts.

As Jago’s (2013) research suggests, jazz performances come with certain expectations, and if musicians indulge too much, their intent may get lost. Even if the musician’s intent is not to release a perfect take, there is a danger in removing the humanity in artistic performance. How interesting it is that today’s students and nascent composers refer to Auto-Tune as a verb. The point being that by using pitch correction, a producer can “fix it in the mix”. Perhaps the same can be said of using sample libraries to replace drums and horn parts. This is one example where issues of technology-mediated composition could affect pedagogical decisions in a film-scoring course. Using pitch correction could render a gritty vocal take lifeless as could overusing beat-mapping to fix timing issues in the rhythm section.

How perfect should a horn stab be? A three-line horn section certainly has differences in attack, articulation, tuning, and rhythmic interpretation. Nevertheless, for a 30-second radio spot, a passive listener may not perceive these issues or even care. Put another way, as educators, do we focus on stylistic authenticity with software-based tools? Alternatively, is the point for music technology educators to guide students to understand better keyboard shortcuts, mixing, and how to use digital audio workstations and third-party instrument controllers?

Musical Humanity

I use the term “musical humanity” to describe the performance and timbral characteristics of a recorded take. Musical humanity includes tempo fluctuations, intonation, inflection, and timbre. How, then, should a producer consider implementing virtual instruments to accompany a performance already recorded? Should the virtual instrument samples match the musical humanity of the original take? Berliner (1994) argues that within improvised music, the recording studio presents some challenges for musicians used to performing before a live audience.

Players often experience bouts of anxiety and insecurity knowing their recorded performances will be scrutinized (Tomes, 2009). The studio places the musicians under a microscope—albeit one each has some control over when collaborating with experienced sound engineers (Berliner, 1994). The recording engineers potentially exert influence on the sound of the improvisations with effects, equalization, and microphone choice (op. cit.). Depending on where and how a studio integrates into a composer’s workflow, these issues can complicate things.

For the composer tasked with working independently, the “studio” most likely exists in his or her DAW. Therefore, they function as an arranger, an orchestrator, and as a multi-instrumentalist. Composers new to a particular style may experience frustration in trying to mimic certain instruments. Do we then, as educators, focus on stylistic versatility or on getting something “close enough”? From a theoretical perspective, do we teach our students deep listening skills, or simply help them to use technology to create a reasonable facsimile? Indeed, no composer can master every instrument nor do professionals have the luxury of unlimited budgets and time to experiment with no constraints. Nonetheless, are we talking about these issues in music technology courses and engaging our students to think about the realities of commercial composition?

Hill (2013) notes that every musical imperfection, especially in live improvisations, breeds a physical element inspiring players to look at their full range of emotions. In the confines of the recording studio, the soloist is exceptionally vulnerable, as the microphones expose and document every nuance of the improvisation (Berliner, 1994). Tomes (2009) argues that although mistakes happen, musicians are intensely focused on not committing errors for the sake of their performance and that of the band. What we now realize is that microphones and recording technology expose both the performance and the human experience inside the studio. Noting Tomes’ (2009) point, as music technology educators, could we guide our students to bring out the nuances in recording and in the use of sample libraries to facilitate recorded takes being more “real”?

Eno's (2004, p. 128) notion of “detached recording” suggests that sound documentation inspires a reactive immediacy; this immediacy is a direct result of the performance's removal and transfer from a studio space to a tangible product. Put another way; human beings long to feel what the musicians felt the moment they recorded each song. Nevertheless, a listener cannot relive a sonic experience in the same fashion. The jazz aficionado’s passion for deep cuts exemplifies this concept as they purchase many versions of the same record over time. The listeners' experiences and perceived meanings of those experiences are direct, transferable, and globalized at the same time (op. cit.).

The detached recording has significance for the producer as well. Advanced technology enables the music producer to reinvent their creative process, regardless of the studio and recording site (Eno, 2004, p. 127-130; Born, 2005, p. 25-26). The detachment itself, although complex, inspires self-sufficiency in the improvisational, compositional, and musical development of new ideas. Producers aim to document exciting moments throughout a recording, and they aspire to release music that resonates with loyal fans regardless of the format.

It makes little difference whether the recording happens in digital or analogue, the philosophy behind the production is the essence of creativity. From this, as music technology educators, we can surmise that decision-making is an essential facet in determining how best to deploy sample libraries and related tools in scoring projects. When assigning scoring and orchestration projects, class discussions might include a component on how producers and music supervisors make creative decisions and why the film scoring industry requires certain aesthetics in jazz and contemporary styles.

Originally, the listening experience, limited to an LP, engaged and inspired committed fans through repeated plays. That detachment removed the listener, and maybe even the producer and session musicians, from an isolated performance in the studio, and placed them wherever the record player resided. Katz (2010) argues while album portability spread jazz to new regions, it removed the music from localized communities and de-emphasized the visual connections performers have with their audience. Today that detachment extends to the instantaneous and digitized information exchange the Internet facilitates. Medbøe and Dias (2014) reflect on the modern jazz musician’s relentless pursuit of masterful playing technique and improvisational skill—noting that while some players hang onto dated methods of reaching an audience, new generations of musicians aspire to reinvent how to spread jazz to the public.

Mendonça and Wallace (2004) argue that improvisation, much like composing, follows a detailed system of patterns and events. Developing sophisticated ideas includes experimenting with melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic vocabulary, which renders musical ideas into a cohesive artistic statement (op. cit.). Just as composers analyze and emulate particular styles, improvisers develop their voice through rehearsed ideas and observant listening to other players (Mendonça & Wallace, 2004).

Improvisation favors urgency and the willingness to explore a new musical vocabulary. Mendonça and Wallace (2004) see innovation as the driving force behind successful jazz improvisation. By today’s standards, compositional improvisation might closely resemble the sampling and remixing methods found in hip-hop and similar styles. How forward thinking is it to include a module on the production aesthetics of an MC or EDM producer? Could that type of subject matter “fit” in a film scoring or jazz-arranging course?

These examples—presented by noted scholars from several musicological perspectives—offer some insight into how technology influences the complex improvisational language. Although a complete review of jazz recording and the technology associated with it extends beyond this paper’s scope, a basic understanding of the intricate tools used to capture and shape sound builds a basis for the deeper appreciation of the influence recording technology has on jazz improvisation. Jazz favors a strong rhythmic drive, creative melodies, and interactive playing. Technology-enhanced accompaniment must not detract from these essential characteristics and the following case study offers a view on how complex decisions come about.

Research Methodology

This project balanced artistic and theoretical aims. A literature review found few if any, similar qualitative studies researching the connections amongst audio and software-based production, jazz improvisation, and creative analysis from the composer and sound engineer’s point of view. Candy (2006) notes that if the finished work is the focal point of the research itself, the task is practice-based. That portion of this study took place in September 2007 and between May 2013 and May 2014 followed by additional data collection and analysis in September 2014 and July 2015

Frith and Zagorski-Thomas (2012) suggest that the multi-layered and emergent scholarly discourse about record production, often organized from historical, theoretical, and empirical perspectives, spans many disciplines in the humanities. As an open-ended subfield drawing from popular music studies, audio engineering, musicology, and similar disciplines, conversations in the growing community of record production scholars aim to unify academic and industry-based views (Frith and Zagorski-Thomas, 2012). “Sanctuary” functioned as a useful beta test to explore how modern technology changes an existing jazz recording.

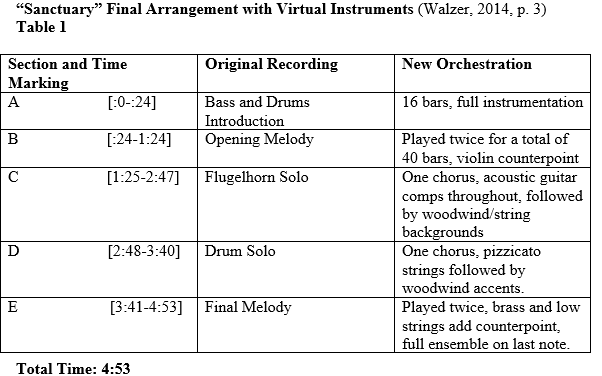

“Sanctuary” was converted into an MP3 file, exported from the DAW (with new accompaniment included), and organized accordingly against a timeline (Walzer, 2014). This data, discussed in detail in the Production and Analysis section of this document, helped to organize the major benchmarks of the recording. An excerpt of the MP3 recording—paired with Table 1 below—allows for close analytical listening of the production approaches discussed elsewhere in this paper. The media is an important component of evaluating the overall success of the project, as each listener must experience the recording to gauge how the accompaniment interacts with the trio recording. Moreover, the composite recording gives the listener a chance to hear the new accompaniment in context.

Since the final “Sanctuary” score wrapped production nearly seven years after the original recording sessions, the study required some retracing of technical and performance information. For ethical and confidentiality reasons, “Sanctuary’s” original engineer is referred to as Sound Engineer and the recording environment is called the Studio (Creswell, 2009, p. 88-91). Initially, an unstructured interview with the Sound Engineer offered beneficial preliminary background information about the Studio, the recording space where the original sessions occurred. The unstructured interview, conducted on 11 September 2014 via online chat, proved helpful. The Sound Engineer contributed essential data on the session’s technical specifications while providing a friendly, open-ended perspective that helped solidify the project’s research aims (Cohen & Crabtree, 2006). Notes taken during the interview supported the casual nature of the conversation (Punch, 1998).

Later, to glean accurate information about the Studio, I sent the Sound Engineer six questions to answer via email [Found in Appendix A]. Meho’s (2006) qualitative research with asking in-depth questions via email, often involving multiple exchanges with interviewees asynchronously, suggests that such approaches are cost effective, reduce geographic constraints, are flexible regarding scheduling, and streamline the transcription process. The Sound Engineer now lives in another state and time zone, and this approach ensured that he could answer the questions thoroughly without the need for face-to-face interaction. Furthermore, the Sound Engineer’s answers—sent on 11 July 2015 and lightly edited for clarity and length, were kept confidential (op. cit.).

Project History, Recording Information, and Production Analysis: (2007)

“Sanctuary”, a composition for flugelhorn, acoustic bass, and drums, dates back to 2007 (Walzer, 2007-2014). The piece’s name drew inspiration from the cathedral’s beautiful acoustics and natural reverberation (Author, 2014; Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 Sept. 2014). Moylan (2012, p. 163) notes that “the spatial qualities of the level of the overall sound are (1) the characteristics of the perceived performance environment and (2) the dimensions of the sound stage.” The Sound Engineer provides specific information concerning the dimensions of the room and the acoustic environment:

“The main live room is approximately 48' deep by 24' wide with a 14'x12' choir section. The ceiling in the live room was sharply sloped and approximately three stories tall at the peak. The back wall of the room is a roll-up wooden door, which separated the large room from a smaller chapel. The pulpit served as a drum riser, 2' tall, wooden, hollow underneath, and filled with carpet padding to reduce boominess. The floor of the room is original 1890's hardwood. Sonically, the room has a very long reverberant tail of about 1 second, brightened by the plaster ceilings and walls, which are all plaster over brick. Several padded pews were placed in the congregation area of the live room to reduce excessive echoing.” (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015)

Bruce and Jenny Bartlett (2009, p. 287) discern that a proper acoustic setting heightens the indispensable characteristics of a transparent jazz recording (cohesive balance, natural reverberation, and listening perspective). The church was an ideal space to record an acoustic jazz trio and provided inspiration for the composer (Walzer, 2014; Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 Sept. 2014). Additionally, the church’s rich history, dating back a century, provided much creative inspiration for artists in the local area including the Sound Engineer:

“The space was a German Presbyterian church, built in 1899, and utilized as an active church until sometime in the early 1990's, when it was bought by a private individual and used as a residence and workshop for building custom hand drums. I met the owner and worked out a deal to rent the large room and pastor's office as studio space.” (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015)

The original recordings included many technical and logistical decisions about musician placement, which helped with visibility and to optimize signal flow. Tzanetakis, Jones, and McNally (2007) note the panning decisions of lead instruments of an acoustic jazz ensemble remain steady over time. The church’s natural reverb allowed the Sound Engineer to experiment with stereo microphone placement on the “Sanctuary” sessions and other recording projects:

“[T]he space and beautiful reverberation of the live room allowed me to use a stereo mic pair to create reverb on albums without having to resort to using any non-organic reverb. It also inspired a few clients to record quieter and more ambient songs they wouldn't ordinarily have explored.” (Sound Engineer 2015)

Figure 1: Drums with overhead microphones

The strategic location of the drums on the stage also compensated for the missing harmonic instrument. Spreading the flugelhorn and double bass ten feet apart in a triangle reduced bleed between the instruments (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 Sept. 2014). The bass drum, snare, and toms had close microphone placements with the overheads configured in a specific position after some experimentation (Walzer, 2014; Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 Sept. 2014).

The adjustments to microphone and musician placement ensured consistent sonic and performance quality of the recorded takes. Crooks (2012) observes the frequent listening disparities amongst rhythm sections, recording engineers and audiences noting that what rhythm section players hear during the performance greatly differs from the final version. Although the first sound checks required some microphone and level fine-tuning, the musicians felt comfortable and played “Sanctuary” in two takes (Walzer, 2014; Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 Sept. 2014). Those decisions made the initial mixing process uncomplicated.

Figure 2: Another drum perspective during the tracking session

The Sound Engineer’s careful attention to musician and microphone placement included some testing to make sure the church’s natural reverberation remained controllable:

“The room required a fair amount of gobo control to separate the instruments and reduce reverb in the mics. I used repurposed doors from the church as transparent gobos to create a space between the bass, flugelhorn, and drum kit and still allow each of the musicians to have sightlines. Because of the room size and sound, I made sure to add room mics to the mix to capture the reverberation of the band playing as a group.” (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015)

Production Decisions: What is Appropriate?

Electroacoustic artists, soundscape composers, and music scholars contend that producers must consider and respect the environment where they record, adopt a thoughtful approach to creativity, and employ production decisions that do not distract the listener (Norman, 1996; Drever, 2002; Oliveros, 2002; Born, 2005; Gluck 2008; Truax, 2012). When the producer introduces audio effects, virtual instruments, synthesis techniques, and editing, they change the character and timbre of the original piece.

Though “Sanctuary” was not recorded outdoors, the same premise applies. An old German church with wooden, vaulted ceilings offers an ensemble a rich, robust acoustical environment to perform and record music. The original recording relied on the deliberate placement of each musician to optimize sightlines and maximize the room’s available soundstage. The challenge, then, is to choose high-resolution samples and then arrange and mix those samples to sufficiently mimic a fused recording site. The production decisions employed many years after the original recording had to support the church where the sessions took place. This philosophy affected the production and editing decisions several years in the future.

“Sanctuary”—Five Years Later (2012-2013)

Although the “Sanctuary” sessions accomplished desired results, the original mixes remained on a hard drive for many years. Furthermore, after archiving the sessions, an unforeseen hard-drive crash erased the finished multi-tracks. Only the remaining stereo mix from the original sessions survived which then necessitated a re-arranged piece for a jazz trio and virtual instruments (Walzer, 2014). Here, virtual instruments refer to the software-based synthesizers and sound libraries found in the DAW.

Modern composers face a dilemma, writing music considered “playable” by real musicians versus optimizing sample libraries to fulfill scoring demands with technology (Asher 2010; Walzer, 2014). With patience and a little mixing knowledge, composers optimize sample libraries to produce beautiful scores used in TV and video. Sample libraries improve year after year, both in audio quality and in performance realism. Although modern technology and sample libraries generate impressive results, they do not replace human players.

As noted earlier in this paper, composers for visual media have robust tools available to craft beautifully interesting work. Perhaps, then, the guiding question relates to how “real” the parts should be. Addressing this point depends on the composer’s intent and the context where the decisions are made. Thus, the case study presented here may offer some helpful context—albeit somewhat conservative given the nature of an intimate jazz recording. From a pedagogical standpoint, is it possible to find a helpful balance? Rather than viewing authenticity as a black or white, all or nothing choice, could composer-educators integrate parts sculpted to mimic some realism and some artificiality? Moreover, could we guide our students to be open-minded and curious about the sounds they choose to include in their work?

Asher (2010) argues that certain projects may not require or demand realism; rather, the composer should focus on their available instruments and create the work they see fit. Meditating on these limitations and tendencies in film scoring, I employ the term “hybrid ensemble” to describe the mix of acoustic and software-based instrumentation (Walzer, 2014). Although virtual instruments offer much in the way of creative possibilities, I found myself questioning if their use in a prior jazz recording would benefit or deter the new film project. In due course, I realized using the remaining “Sanctuary” master would serve a greater purpose than simply wasting away on a hard drive. Since the original recording space had a bright, reverberant sound, aggressive use of effects proved unnecessary (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015).

A few broader questions came up after reflecting on the time it took to align the original recording and the new accompaniment. For example, would listeners appreciate how hard it is to synchronize a live performance to new parts after the fact? Have I just ruined a beautiful recording by adding unnecessary parts? Beyond the technical and logistical issues, many artistic questions arose throughout the production cycle. Considering that the original recording remained dormant, and the fact that the new combined instrumentation might serve a useful purpose, it seemed appropriate to continue exploring how these elements could work creatively.

“Sanctuary” Recording for Playback (Walzer, 2007–2014)

Discussion

The “Sanctuary” project, while exploratory, achieved several goals. Foremost, the completed hybrid piece served as the opening cue in a documentary movie. The film’s opening sequence matched “Sanctuary” regarding pace and mood. Second, while an exciting jazz recording session floundered due to an unfortunate technical glitch, the remaining artifact from those original sessions provided inspiration for a new work accompanying visual media. An important aspect in determining the quality of the original “Sanctuary” project includes how the Sound Engineer broadly perceives his role in capturing improvised music:

“My primary focuses are capturing the energy of the group, making sure they have good headphone mixes so they can get a good vibe from each other, capturing the sound of the instruments without unnaturally hyping or losing any of the sonic characteristics, and staying out of the way of the music.” (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015)

The Sound Engineer’s observation on “unnaturally hyping” the sound echoes the arranging, compositional and mixing approaches during post-production. Each of the research questions hypothesized about whether a) the technology aided in synchronizing a live recording with new accompaniment and b) employing a judicious approach—both musically and sonically—would detract from the original aims of the “Sanctuary” recording (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015).

The original sessions were interactive, playful, and distinct due to the size of the room and its desired acoustics. As the Sound Engineer thoughtfully observed: “staying out of the way of the music” included avoiding any unnecessary production during orchestration and in the final mix (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015). A conservative choice of new sounds and use of effects shifted the focus back to the original recording. The post-production aspects of this project remained sparse. Humanizing virtual instruments through data manipulation can only do so much in the absence of actual players.

I viewed the arranging and production facets of this project from multiple perspectives. Doing so gave me a better understanding with which to make aesthetic decisions. The original recording, both interactive and honest, stood proudly. The trio’s sympathetic and creative playing demonstrated a commitment to focused listening and collaborative improvisation. Regardless of the kind of orchestration used, the trio’s interplay remained the focal point of the entire project. Every technology-mediated decision considered how the virtual instruments should support, and not dilute the overall performance. While the composition’s new accompaniment sections were subtle, their bearing, coupled with thoughtful mixing, brought clarity, and depth to previously recorded acoustic improvisations. “Sanctuary”, as a jazz waltz with brushes, required a sensitive arrangement and pragmatic orchestration.

Orchestrating virtual instruments to an existing audio recording presents many obstacles. Locking virtual instruments to a live track demands tremendous organizational skills. Through meticulous planning, musical sensitivity, and thoughtful experimentation, it is possible to blend live audio recordings with virtual instruments, albeit with modest results. This project revealed that conservative use of digital tools, although limiting at times, removed the focus from technology and placed it back on the music. Looking back on the original 2007 recording and the entire orchestration process several years later, the Sound Engineer and I share a common respect for emphasizing the intent of the music itself. When asked if modern technology influences the Sound Engineer’s production aesthetics, he responded as follows:

“Not particularly. Modern recording technology allows me to work very quickly and keep the musicians in the flow of the music and vibe of the song, but the styles of music I work on are all over the place, and my primary focus is capturing and enhancing the intent, energy, and musicianship of the group.” (Sound Engineer, personal communication, 11 July 2015)

Modern record production software allows for extensive audio editing, mixing, and synchronization with video. Concerning “Sanctuary”, the overarching goal to create the new accompaniment was to preserve the integrity of the original recording through available technology. How “authentic” the orchestration was in this context is a matter of subjective perception based on the listener’s interests in creative improvised music.

Conclusion and Reflections for the Future

This study revealed that conservatively adding virtual instruments minimally changed the original recording’s timbral qualities. However, exercising ‘production restraint’ was a conscious choice not to dilute the beautiful acoustics and interactive playing of the trio. Panning decisions, use of reverberation and other effects, and scoring/arranging considerations aimed to focus on the trio and employ the virtual instruments as a simple accompaniment. MIDI data, though configurable to an extent, is not the same as “musical humanism”.

Looking at this from a pedagogical standpoint, I might remind students that certain parts of the scoring industry demand perfection. Other areas give the composer more freedom to customize sounds and arrangements to be exploratory and even experimental. Using a preexisting jazz recording does not speak to the myriad of available styles. That said, I learned a tremendous amount participating in the project and even more engaging with my Sound Engineer friend and colleague.

Samples, no matter the quality, cannot correctly match the cry of a flugelhorn, a bass player’s intonation, or the sound of a drummer’s brush on a cymbal. That is not the point of using virtual instruments. In this study, the MIDI technology fulfilled a necessary role to flesh out an unreleased trio performance. In that context, the software-based accompaniment functioned beautifully—allowing for editing, experimenting, and renewed creativity. Incorporating contemporary technology is a means to an end. In this study, the Sound Engineer and I understood that losing the multi-track sessions was an unfortunate event. Reinvigorating the project with MIDI technology proved to be at best a fun experiment, though the study’s results do not suggest that our perceptions of creativity in the studio have changed all that much. As an educator, I admit readily to sharing this experience with students, encouraging them to always save previous recordings in multiple places.

Musical humanism seems to be a core aspect of jazz performance and composition. Producers and sound engineers aspire to capture these elements in recordings to be released. Though players can overdub and layer parts, what makes jazz so compelling is the feeling behind the musicianship. This study required mapping out an accompaniment that adjusted to various tempo fluctuations. The point of the accompaniment was never to dilute the humanity of the trio’s original take. This paper investigated instances of jazz musicians engaging too much with the technology, but there are successful examples to which one can listen.1

The “Sanctuary” project required scoring retrospectively because of the loss of earlier work. The rareness of this scenario does contribute to the limitations of the study. As an arranger, audio engineer, and multimedia producer, I had to integrate the DAW’s sophisticated editing features in an asynchronous fashion. Although the technology facilitated such an approach, it is not as desirable when real players are available. “Sanctuary” sat idle for so long that aspiring to use it in some way seemed like a novel idea with little inherent risk. Additionally, what works for jazz may not work in other styles of music. That much is clear.

“Sanctuary’s” modest success as a composite work lies in an extensive post-production effort coupled with a patient, conservative scoring treatment, detailed organization, and focused audio editing. The original technical loss of data does contribute to the limitations of the study. Considering these factors, revising “Sanctuary” allowed the track to be repurposed—albeit many years later. From that perspective, the overall project was a success, however, the compositional approach is less than ideal when employed so long after the fact. Therefore, the approaches discussed here may not be applicable in other scoring and pedagogical contexts.

Future studies must include a broader sample size to generate interview data. Shortly after the original sessions, I moved to a different city and many years passed before revisiting the “Sanctuary” project. Interviewing the engineer for “Sanctuary”, although unstructured, brought new technological and musical perspectives to the task. The musicians on the original session were contracted for hire. Indeed, not getting their perspectives, as the session occurred, contributes to the limitations of the sample size.

In the future, interviewing the musicians and audio engineer during the session would provide valuable data to cross-reference with the post-session interviews. Using affordable new media technologies to document the session’s events through photographs and video blog enhances the project. Additional case studies, artist interviews, and commercial recordings promise to shed light on these issues. These points might also extend to the ways that music technology educators consider case studies in their modules. Qualitative research via media ethnography could prove advantageous as music educators consider how industry determines realism and how composers must adhere to certain professional standards.

Future studies may consider using these tools to test how record production approaches change from pre-production to commercial release, particularly with live performances and recordings using non-traditional media. This research need not be restricted to the studio. Furthermore, the scholarship must explore the music audience’s perception of such actions. As more literature examines how music is produced, distributed, and analyzed, future studies must look at how modern technology shapes the space where improvisation happens.

With care, it is possible to use this technology to enhance, not replace, existing recordings. Technology-based composition and improvisation require musicians and audio engineers to use their ears while remaining truthful to their aesthetic interests. Doing so ensures the technology positively connects their musical ideas with useful tools to maximize creative practice.

This paper presented a series of exploratory questions about how the recording studio, and related production technology, shapes our perception of realism and listening in jazz styles. We can draw parallels to other modern forms of music and encourage students to think carefully and critically about the technologies employed throughout a project. Moreover, as music technology educators, if we can draw parallels to the philosophical issues underpinning sonic perfection through audio editing, MIDI optimization, and the like, perhaps we can prepare students for the rigors and challenges of what it means to produce something that meets an “industry standard”. What is clear is that an integrated curriculum that includes music composition and digital audio fundamentals, diverse listening examples, and discussions on artistic intent, enhance student understanding of the many issues facing contemporary music technology.

Notes:

1 In addition to the Bill Evans and Lennie Tristano examples presented here, interested readers may choose to explore Natalie Cole’s recorded work with her father, Nat King Cole and Ray Charles’ posthumous recordings with the Count Basie Band. See http://www.allmusic.com/album/ray-sings-basie-swings-mw0000778469.

References:

Asher, J. (2010). Composing with sample Libraries: Make it “real” or make it “good”. Film Music Magazine. Global Music Online, September 2010. Retrieved from Film Music Magazine.

Bartlett, B., & Bartlett, J. (2009). Evaluating sound quality. In Russ Hepworth-Sawyer (Ed.), From demo to delivery: The process of production [Google books version], 279–288. Boston: Elsevier/Focal Press. Retrieved from Google books.

Berliner, P. (1994). Thinking in jazz: The infinite art of improvisation [Kindle version]. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Born, G. (2005). On musical mediation: Ontology, technology and creativity. Retrieved from twentieth-century music 2(1), 7–36.

Brock-Nannestad, G. (2012). The lacquer disc for immediate playback: Professional Recording and home recording from the 1920s to the 1950s. In S. Frith & S. Zagorski-Thomas (Eds.), The art of record production: An introductory reader for a new academic field [Kindle version], Surrey: Ashgate. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Candy, L. (2006). Practice based research: A guide, 1–3. Retrieved from http://www.creativityandcognition.com/resources/PBR%20Guide-1.1-2006.pdf.

Creswell, J. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles: Sage.

Cohen, D., & Crabtree, B. (2006). Qualitative research guidelines project. Retrieved from http://www.qualres.org/HomeUnst-3630.html.

Crooks, J. (2012). Recreating an unreal reality: Performance practice, recording, and the jazz rhythm section. Retrieved from Journal on the Art of Record Production 6.

Drever, J. (2002). Soundscape composition: The convergence of ethnography and acousmatic Music. Organised Sound, 7(1), 21–27. Retrieved from http://alturl.com/ocrzc.

Eno, B. (2004). The studio as a compositional tool. In C. Cox & D. Warner (Eds.), Audio culture: Readings in modern Music, 127–130. Retrieved from New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Frith, Simon, and Zagorski-Thomas, S. (2012). Introduction. In S. Frith & S. Zagorski-Thomas (Eds.), The art of record production: An introductory reader for a new academic field [Kindle version], Surrey: Ashgate. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Gluck, R. (2008). Between, within and across cultures. Organised Sound, 13(2), 141–152. Retrieved from http://alturl.com/xqeob.

Hill, S. (2013). “An invitation for disaster”—Embracing the 'double failure' of improvisation. Retrieved from Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, 9(2).

Schmidt Horning, S. (2012). The sounds of space: Studio as instrument in the era of high fidelity. In S. Frith & S. Zagorski-Thomas (Eds.), The art of record production: An introductory reader for a new academic field [Kindle version], Surrey: Ashgate. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Jago, M. (2013). What is a jazz record anyway? Lennie Tristano and the use of extended studio Techniques in jazz. Retrieved from Journal on the Art of Record Production 8.

Katz, M. (2010). Capturing sound: How technology has changed music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Medbøe, Haftor, & Dias, J. (2014). Improvisation in the digital age: New narratives in jazz promotion and dissemination. Retrieved from First Monday 19(10).

Meho, L. (2006). E-mail interviewing in qualitative research: A methodological discussion. Retrieved from Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(10), 1284–1295.

Mendonça, D., & Wallace,W. (2004). Cognition in jazz improvisation: An Exploratory Study. Retrieved from 26th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. Chicago: Cognitive Science Society. 1–6.

Monson, I. (1996). Saying something: Jazz improvisation and interaction [Kindle version], Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Moylan, W. (2012). Considering space in recorded music. Retrieved from the S. Frith & S. Zagorski-Thomas (Eds.), The art of record production: An introductory reader for a new academic field [Kindle version], Surrey: Ashgate.

Norman, K. (1996). Real-world music as composed listening. Retrieved from Contemporary Music Review, 15(1-2), 1–27.

Oliveros, P. (2002). Quantum listening: From practice to theory (To practise practice). Retrieved from S. Chan and S. Kwok (Eds.), Culture and humanity in the new millennium: The future of human values. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to social research: Quantitative & qualitative approaches. Sherman Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tomes, S. (2009). Learning to live with recording. In N. Cook, E. Clarke, D. Leech-Wilkinson, & J. Rink (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to recorded music [Kindle version], Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Truax, B. (2012). Sound, listening and place: The aesthetic dilemma. Retrieved from Organised Sound, 17(3), 193–201.

Tzanetakis, G., Jones, R., & McNally, K. (2007). Stereo panning features for classifying recording production style. Retrieved from ISMIR (Ed.), Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Music Information Retrieval: 14-18 September 2008, Drexel University. Philadelphia: International Society for Music Information Retrieval.

Walzer, D. (2014). Creative arranging and synthestration with MIDI virtual instruments in a jazz recording and film scoring context. Retrieved from ATMM (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2014 Audio Technologies for Music and Media Conference, Ankara: Bilkent University, 1–8.

Walzer, D. (2007–2014). Sanctuary (Unreleased trio recorded performance from September 2007). MP3 file.

Appendix A: Sound Engineer Interview Questions

1). Can you describe some of the physical dimensions and acoustical characteristics of the church space you used as the Studio?

2). Can you describe the history of the space and why you chose to set up a recording studio there?

3). What kind of influence did the cathedral have on the types of music you recorded there? Did the space influence your mixing and production aesthetics or workflow?

4). Regarding the “Sanctuary” sessions, what kind of sonic or musical influence did the church have on your mixing decisions?

5). As a sound engineer, what is your primary focus when recording jazz and improvised music?

6). Does employing modern recording technology influence the different styles of music you produce and record?