“Be Prepared”

— Boy Scout and Girl Guide motto

The concept of preparation implies readiness for as many eventualities as possible. Robert Baden-Powell, who inspired the Boy Scout movement with his book, Scouting for Boys, described preparation as being in a constant state of readiness in mind and body in order to do one’s duty. This “duty” sense of preparation carries with it a high degree of obligation. Indeed, those of us in higher education do have an obligation to help prepare students for their future and their duty, whatever that may be. Preparation, however, is predicated on a high degree of certainty. We can prepare adequately for the future because it looks an awful lot like the present and past. Problems, arise, however, when the future no longer resembles the present or past.

The authors in this article raise questions about what it means to “prepare musicians” for the world they are expected to inhabit. The invocation “be prepared” implies predictability: prepare for what, exactly? Visiting the College Music Society website in 2017 gives one an immediate sense of the higher education music climate surrounding “preparation.” The page views differ slightly depending on if you are logged on or not, but there is no escaping that “the future of music [training]” is a theme taken seriously by CMS. What else is one to make of such language as “exploring change through bold innovation,” “transforming the education of musicians,” and “accelerating change in the education of musicians”? These headings are, at the time of writing, all found under the banner of “Creating Music Curricula of the Future,” where members are encouraged to join the CMCF mailing list, gather colleagues to create a Task Force, write articles, develop surveys and webinars, and submit proposals for upcoming conferences.

Seemingly building upon the 2014 (revised, 2016) “Report of the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major” and the 21st Century Music Schools Summit in 2016, “Creating Music Curricula of the Future” appears to be a concerted effort on behalf of CMS to mobilize substantive change in curricula for university music majors, a program of study that has arguably experienced little more than “surface” changes over the past hundred years or so. In the assessment of the TFUMM report, “There have been repeated calls for change to ensure that musical curricular content and skill development remain relevant to music outside the academy. The academy, however, has been resistant, remaining isolated and, too frequently, regressive rather than progressive in its approach to undergraduate education” ("Report on the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major, p. iiiTask Force on the Undergraduate Music Major. (2014). Transforming Music Study from its Foundations: A Manifesto for Progressive Change in the Preparation of Undergraduate Music Majors. College Music Society.).

This article is based on a panel presentation at the 2016 College Music Society Conference in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Our intention was (and is) to contribute to the dialogue about undergraduate music preparation. While we are generally in agreement with many of the ideas set forth by others interested in this topic, we believe that several issues related to engagement, such as digital musicianship, underserved students, entrepreneurship, global music studies, and service learning bear additional discussion.

Technology Integration: Toward “Digital Musicianship” (Greg McCandless)

With the exception of niche degree programs, the core curriculum of higher education, in being primarily performance-focused, invariably fails to address music production, which in turn limits our schools’ collective engagement with the commercial music community. This exclusion has its roots in the expense and complexity of recording technology, which in the past required large budgets and the hiring of engineering specialists. However, digital music production software is now ubiquitous (owing to its increasingly low cost)11 For example, Pro Tools, an industry-standard digital audio workstation (DAW), debuted in 1991 at a cost of $6,000 (Watson, 2015, 22). Today, Avid's Pro Tools 12 can be downloaded by faculty and students for $299, while the stripped-down Pro Tools First is completely free., and the rise of helpful tutorial offerings via YouTube, Lynda.com, MacProVideo, etc., has made it possible for any contemporary musician to learn a little about production.

We typically equate conservatory “community engagement” efforts with human engagement, with either faculty or music majors physically leaving the building (to, for example, put on a public concert, or visit a high school or hospital) or bringing non-majors into the building (with community ensembles, non-degree study programs and workshops, etc.). I have instead been focused on curricular engagement in order to create connections with populations by addressing their interests and language in coursework, with a focus on music production in particular. The most straightforward type of curricular engagement involves adjusting repertoire to address various communities—to simply incorporate more styles of music into the core. Indeed, there have already been quite a few “Manifesto”-prompted suggestions for curricular revision aimed at doing so.

A significant contribution to the discussion is John Covach’s (2015a) recent article in The Chronicle of Higher Education, which led to his more detailed proposal for a core curriculum that incorporates a diversity of styles, including popular music. While I agree that we need to continue to integrate a wide variety of genres into our curriculum, the problem with the core is not chiefly one of genre limitation. I believe that we need to focus instead on a different type of “integration:" the integration of theory/composition topics and audio engineering/sequencing techniques into our core curriculum to promote what Brown (2012), Hugil (2008), and others have dubbed “digital musicianship.” Such an integration of skills allows our students to, among several other things, engage with—or simply converse with—commercial musicians.

A primary benefit of “digital musicianship” is that it addresses a root cause of the divide between our curriculum and the commercial music community: our persistent attachment to a live performance-based concept of music making, which in turn is reflected in the elements we prioritize when describing musical structure. The concert-based musical life cycle goes something like this: concept/inspiration leads to notation, performance, and, ultimately, reception. Resulting from this performance orientation is a musicianship core that treats music as being composed of pitch/melody, harmony, rhythm, and form; music theory and aural skills courses thus address these domains exclusively, even those that purport to address commercial music by incorporating a diversity of genres. On the other hand, a contemporary commercial understanding of music making regards the life cycle as follows: concept/inspiration leads (optionally) to notation, performance, recording/sequencing, editing, mixing, mastering, bouncing, marketing, purchase, and reception. A theory/musicianship core that has a legitimate chance of preparing students to craft music for media (such as film music) or any other kind of commercial music should therefore address all of these facets of contemporary music making. Pitch/melody, harmony, rhythm, and form would remain the focus of such curricula, but would be joined by dynamic and timbral topics such as compression, equalization, effects processing, automation, panning, and mastering. This would in turn require instruction on the basics of audio and MIDI at the outset of the core.

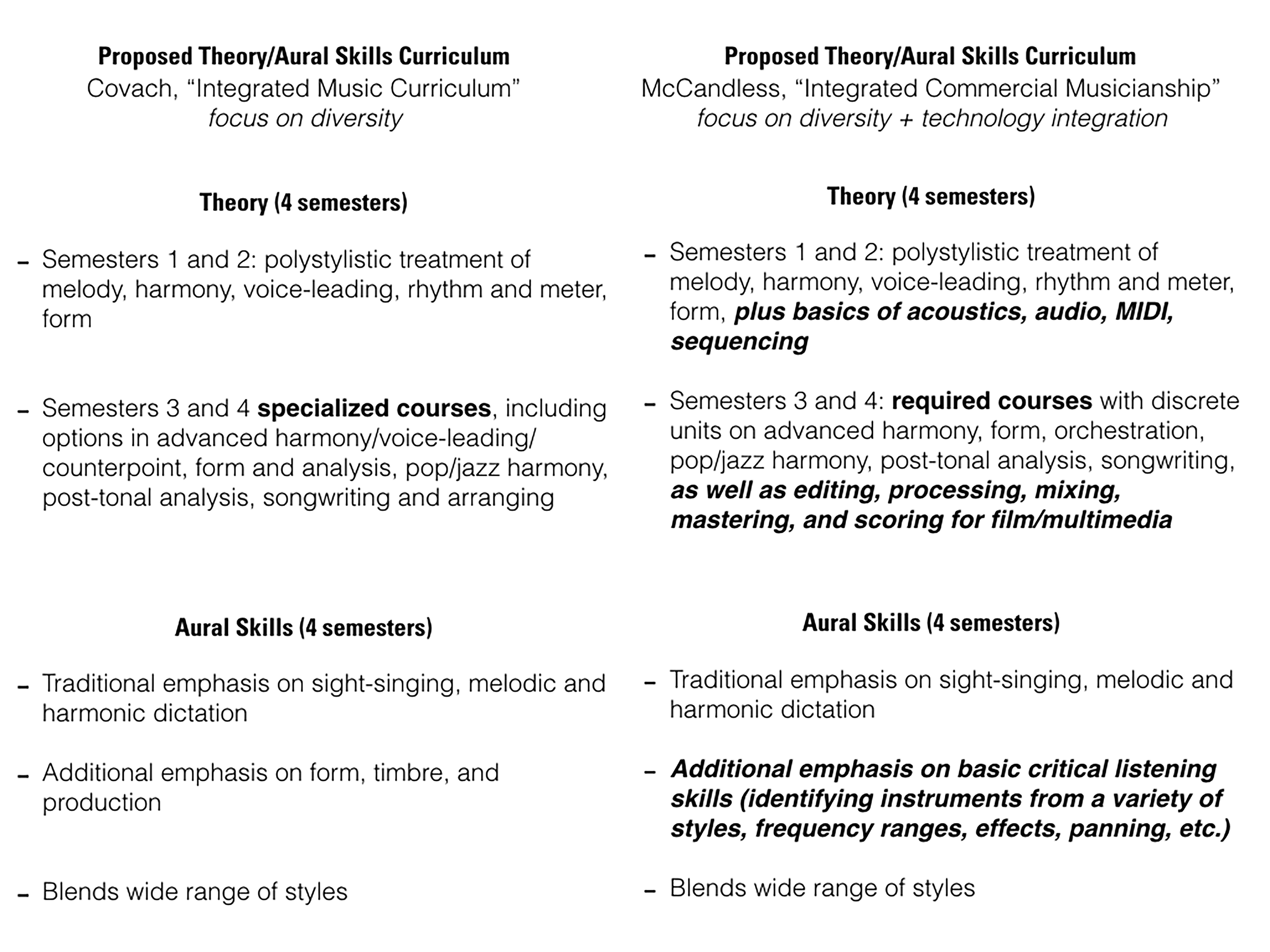

My initial proposal for technology-integrated musicianship training is provided below, side-by-side with John Covach’s (2015b) proposal for stylistically-integrated musicianship training.

Figure 1: A comparison of proposals for integrated musicianship training.

While Covach’s proposal appears to meet his goal of increased stylistic diversity, it does not emphasize the music production training that was initially acknowledged in his Chronicle article as being a pillar of commercial music programs. In my proposal, instruction on audio and MIDI is provided at the very outset of the theory sequence, which in turn allows students to actually “produce” short composition assignments. In fact, we are already experimenting with this at Appalachian State University, as students are required four times per semester in each theory course to craft brief, topic-relevant compositions that meet certain music-structural guidelines. Students are additionally asked to produce them either via an audio recording or a sequenced mock-up. I have taken these composition project requirements as springboards into deeper discussions of sequencing, editing, mixing, and mastering, and I have already experienced several benefits in doing this, including more students coming to office hours—if only to express their interest in certain pieces of production software (though this generates rapport, too).

My hope is that my proposal in Figure 1 is seen as rather conservative, which I believe it is. I do think that the argument can be made—especially by those who increasingly view the university’s role in society to be a delivery vehicle for professional job skills—that technology-focused production training is necessary for all 21st-century music majors, just as it is for almost anyone who is currently making a living creating music outside of the orchestral performance realm. But that argument is not mine. Instead, I believe that if we, as instructors at universities dedicated to fostering musical knowledge, want to encourage deeper conversations, analyses, and insights into how contemporary music is crafted in a variety of genres, we need to avoid limiting the domains covered by our musicianship courses to those that relate only to the traditional, concert-based music-making paradigm. By incorporating production skills, we may speak to the interests already held by of a sizable portion of our current student body, engage a new population of students who have been knocking on our doors for decades, break down the needless division between “making music for class” and “making music for real,” and prepare our graduates to address a wider spectrum of music making.

This is no easy task, however. There are a variety of impediments related to any potential adoption of this type of curriculum. Among these is faculty training, as very few faculty have production coursework in their backgrounds—even composers, who largely indicate that they have needed to learn this material on their own. Another significant impediment is the age-old depth/breadth issue: that is, if audio and MIDI training are introduced into Theory I, for example, and the semester remains at the standard length, then what gets removed to make room? This is of course an institutional or departmental consideration, but in my own courses at Appalachian, I have simply eliminated second and third lectures on transposing instruments, embellishing tones, and diatonic seventh chords; I also eliminated one of six lectures on fugue. Essentially, it has been a remarkably easy decision-making process for me thus far.

While some depth has admittedly been sacrificed in my theory classes, the benefits have been substantial in my mind. Beyond learning the language of professional commercial musicians, students engaged in digital musicianship curricula are exposed to more authentic assessments, which require them to create music following the same procedures as professionals. Moreover, students who are asked to accomplish production tasks quickly learn that written theory knowledge and music technology proficiency are distinct and complementary. Often, the traditional, formally-trained students are lacking in technological aptitude, while non-traditional students with production skills tend to be weaker with notation and theory. When asked to produce projects that synthesize compositional technique, notation, and production skills, these groups of students (who, in traditional theory courses, tend to represent the “haves” and the “have nots”) readily understand that they possess both strengths and weaknesses, and the natural result is an increase in peer valuation and collaboration.

Engaging Underrepresented Student Populations (David A. Williams)

School music teachers in the United States have a long history of engaging students in one particular type of music making activity. This activity is rooted deeply in the Western European orchestra tradition where a director/conductor leads a large number of musicians as they rehearse and perform music written, almost exclusively, by others. Long ago this model of music making become the benchmark for school music programs in the form of both instrumental and choral ensembles (Mark & Gary, 2007Mark, M. L., & Gary, C. L. (2007). A history of American music education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.). It is now so pervasive that it is taken for granted as the most appropriate and only truly worthy musical practice for the music education profession. What is more, this model of music education has, for a very long time, been self-perpetuating. High School students who are successful and enjoy this musical involvement are often encouraged to matriculate as music education majors in colleges. The degree program in university is normally designed to prepare these individuals to teach music in K-12 schools where they will lead the next generation in the same type of music making activities that they found enjoyable. Then another collection of students will be encouraged to become music education majors in college. And so it has continued for more than one hundred years.

All of this would be fine, except a lot has happened musically over the last century. Today our musical culture is incredibly diverse and opportunities for music engagement are many and varied. Our continued devotion to a singular model of music making tends to ignore this diversity. As a result, our music classrooms often do not represent the heterogeneity that makes up many schools. Data indicate that Hispanic and African American students, non-native English speakers, students with lower GPA’s, those from lower socioeconomic strata, and those with lower achieving parents are all underrepresented in traditional school music programs (Elpus & Abril, 2011Elpus, K., & Abril, C. R. (2011). High School Music Ensemble Students in the United States: A Demographic Profile. Journal of Research in Music Education, (2). 128.; McPherson & Hendricks, 2010McPherson, G. E., and Hendricks, K. S. (2010). Students’ motivation to study music: The United States of America. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 201-213.). It isn’t that these students are not interested in music making opportunities in schools, but rather that schools don’t typically offer musical options that these students find meaningful.

There are examples of music teachers providing non-traditional music classes in an attempt to broaden offerings. For example, over the past several years, many schools have added guitar classes (Shuler, 2011Shuler, S. C. (2011). Music Education for Life: Building Inclusive, Effective Twenty-First- Century Music Programs. Music Educators Journal, 98(1), 8-13. doi:10.1177/0027432111418748). While this is certainly a step forward (fifty years too late!) for the music education profession, we too often are missing a pedagogical opportunity that could make non-traditional music classes even more relevant for students (Williams, 2014Williams, D. (2014). Another Perspective: The iPad Is a REAL Musical Instrument. Music Educators Journal, 101(1), 93-98. doi:10.1177/0027432114540476). Music teachers are well versed in leading ensembles in a teacher-centric model where they make most, if not all the musical decisions, and the student’s role is mainly to follow directions. Modern learning theories question this pedagogical approach (Lambert & McCombs, 1998Lambert, N. M., & McCombs, B. L. (Eds.). (1998). How students learn. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.). “Non-traditional” music classes can provide outstanding opportunities to use learner-centered approaches where students are doing more of the music making work.

I suggest there are at least six overlapping characteristics that could define a learner-centered music classroom that would help make non-traditional music offerings more attractive to currently underrepresented student populations, and would also help those students better develop lifelong musicianship skills.

Student Autonomy. A learner-centered classroom will allow for a significant amount of autonomy where students make decisions regarding musical styles and instruments that will be studied and performed. Instead of solely taking in what they are told, students are given freedom to come up with solutions to problems and questions. This forces students to search for information and to learn on their own with guidance from the teacher. It also allows for students to make significant use of, and adapt, prior knowledge they bring with them to the classroom. Students, of any age, certainly know a lot about music from their experiences outside of school, but traditional methods of teaching typically do not honor this, nor allow students much opportunity to take advantage of it.

Student Creativity. In learner-centered classrooms students will be asked to create original music by composing, song-writing, improvising, arranging and covering. Instead of exclusively studying and performing music written by others, students will work through the process of creating original music. In doing so, students gain insights into the sonic makeup of music seldom achieved through performance alone.

Collaborative Focus. In a learner-centered class, students will work in small groups collaboratively making musical decisions. Small groups of students (2-6 on average) working collaboratively places the burden of problem solving directly on the students. This contrasts with the traditional music performance class where musical decisions are most often made by the teacher, or ensemble director, and then “taught” to the students. Students forced to make musical decisions for themselves are doing the work of musicians, and educational psychology suggests that those doing the work are the ones doing the learning (Doyle, 2011Doyle, T. (2011). Learner centered teaching: Putting the research on learning into practice. Stylus Publishing, LLC.).

Aural Based. In a learner-centered class the vast majority of musical work will be done aurally by students. Western staff notation will rarely be necessary and can be addressed when, and if, students find the need for it. Traditionally, music education has taken the stance that the abilities of reading and writing musical notation are absolutely essential to music making. This tends to be true for only certain musical styles, practiced in specific ways -- these being the styles and ways that are most common in schools in the United States. We do a disservice to students when we so overemphasize the written aspects of music that they begin to see notation as fundamental to understanding what music is about.

Messy. Activities within a learner-centered classroom tend to look messy and unorganized. Traditional performance classes in schools, on the other hand, embrace a philosophy that prizes efficiency, time management, and “discipline.” By contrast, a learner-centered classroom provides time for students to consider, experiment, make mistakes and learn from them. Assignment outcomes resulting within a learner-centered classroom usually unfold over time as students find their way through musical questions and challenges. Learning in this method requires extra time, but the results are normally very meaningful for students and help lead to lifelong musical skill development.

Teacher-as-Resource Guide. The teacher’s role in traditional music programs is well established, but in a learner-centered environment the teacher can take on an ever changing list of responsibilities. Foremost of these is a resource guide whose role is to provide students with the materials and information they need to successfully manage tasks. This role will be different depending on the demands of each student group and teachers need to be flexible, accommodating and open to new possibilities. The most challenging part of a guide’s role, at least for most teachers, is the need to stay out of the way of students as they make decisions for themselves.

A learner-centered music classroom allows students significant autonomy over musical style and instrument choices. This occurs in an environment where, in small groups, they are collaboratively making creative and musical decisions that tend to be aurally based. This setting is usually messy, without many predetermined outcomes, and the teacher’s primary role is to stand back allowing students to work out problems on their own, providing support as needed. Such a classroom provides a music making environment that is often very attractive to the underrepresented student groups that tend not to be interested in our traditional offerings. This pedagogical practice is also inclined to help students develop musicianship skills they will be more apt to use throughout their lifespan. The music education profession, especially in the United States, has a long history of ignoring students who don’t fit the traditional school music mold. It’s about time we get to know these students. They, too, deserve meaningful opportunities to make music in school.

Entrepreneurship in Music Education: A.K.A. “What I learned from the scene about community engagement” (Sarah Gulish)

Engaging a community involves engaging with those beyond the classroom walls. As a high school music teacher, I have noticed the ways in which music-making within school is often isolated from music-making outside of school. This can stand in stark contrast to the call to involve students in lifelong music-making, and to prepare them to engage with musics after they graduate. But, how does such engagement happen? When I entered the field of music education, I felt underprepared to address such large issues. Most of my undergraduate preparation centered on music within the classroom. Fortunately, I had a wealth of experiences as a rock musician that led me to engage in entrepreneurial activity for the sake of making connections as a musician. These experiences formed my philosophy and approach for connecting with community.

Before beginning work in a school community, it is important to first know that community and to question: What are the needs specific to this community? What does this community value? How can mutually beneficial relationships be established between the school music community and the wider community? These are the very questions I asked when seeking to engage in my local context. I teach in a suburban high school, situated in the town of Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania. Many of my students expressed a desire to make music outside of school and to find other performance spaces. To do this, I learned about our community and sought to answer the above questions above.

In seeking to answer the questions about my specific community, I first sought to establish relationships with local businesses and those who lived in Huntingdon Valley. This led me to a local business, Be Well Bakery and Cafe, that was open to live music performances from students. I used this connection and opportunity to develop a “business strategy.” My goal was to host a regular music night at the cafe in which students could sign up to perform music. I wanted this to be an event open to all students, regardless of school music involvement. While I could imagine this event on a large scale, I started with small goals and piloted the event with few students. After achieving success on the pilot night, I sought feedback to revise my strategy and plan for the following school year.

The Be Well music nights are now in their third year of operation. Students are running the shows, developing acts, and practicing on their own. This program serves to provide authenticity for popular music-making that can often be lost when such musics are brought into the classroom (Allsup, 2003Allsup, R. E. (2003). Mutual learning and democratic action in instrumental music education. Journal of Research in Music Education, 51(1), 24-37.; Davis & Blair, 2011Davis, S. G. & Blair, D. V. (2011). Popular music in American teacher education: A glimpse into a secondary methods course. International Journal of Music Education, 29(2), 124-140.; Green, 2006Green, L. (2006). Popular music education in and for itself, and for ‘other’ music: Current research in the classroom. International Journal of Music Education, 24(2), 101-118.; Karlsen, 2010Karlsen, S. (2010). BoomTown Music Education and the need for authenticity—informal learning put into practice in Swedish post-compulsory music education. British Journal of Music Education, 27(1), 35-46.; Vakeva, 2009Vakeva, L. (2009). The world well lost, found: Reality and authenticity in Green’s ‘New Classroom Pedagogy’. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 8(2), 7-34. Retrieved from http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Vakeva8_2.pdf). This example of community engagement has benefited not only my students’ sense of community participation and my own professional growth, it has helped the cafe build business and reach a new customer base. While this is one example of how I personally sought to engage my school’s community, it may help provide insight into the call of teaching undergraduate music students to engage.

If we hope to create college music graduates with a mission for community engagement, we must structure the undergraduate experience to promote just that. First, I think it is imperative to have undergraduate music majors involved in the community. They need to learn to listen to a community’s needs, respond, and find ways in which connection is possible. Music students also need to be taught valuable entrepreneurship skills. For example, most music education majors will assume positions in which they are working with limited resources and insufficient programming. They must learn to problem solve by building and renewing. Much of this requires program advocacy and working with school districts and administrators towards a tangible goal. Finally, to engage with outside communities of music, students must be given the opportunity to interact with types of music-making that represent contemporary popular musics. Students would benefit from learning to use basic music technology and sound equipment. All of these skills benefited me greatly when engaging with my school’s community and setting up a performance space. However, most of these skills were learned through my experience as a touring rock musician, not necessarily from my experience at university. If we can model engagement and encourage undergraduates to engage in tangible ways, the future of undergraduate music preparation education will include much more than what happens within the classroom walls.

Creating Global Community in the Music History Classroom (Ted Solis)

I find myself working to foster community by bringing my students together with their classmates (regardless of particular music major emphasis) and other music students within the School of Music, and to connect them with the university beyond. Moreover, I hope to help them situate themselves vis-à-vis their professions, historical roots as musicians in America, and the global community, in a sort of "You Are Here" map. Although I work toward these goals in all my courses, whether undergraduate or graduate, the particular one to which I refer here is the 100-level "Music as Culture," the first in the Arizona State University School of Music's "Music History" (note that I seldom find myself using that term without scare quotes) sequence of three, required of all music majors. The next two upper division music history courses follow the venerable "before and after 1750" scheme. The "realization" concept overarches much of what I do in this course. For me, "Realization" implies "Reintegration," which also implies "Community." My aims are to de-mystify the Western European Art Music (henceforth WEAM), interrogating its autonomous, received, notation-bound, and exceptionalist status. I want my students to think critically about situating (1) themselves vis-à-vis WEAM; (2) WEAM vis-à-vis American society; and (3) WEAM in world and historical context. I approach this through both "critical writing, and "critical performance.” In this article I discuss the latter.

Critical writing in MHL 140 involves a number of essays on such "realization-related" ideas as Christopher Small's (1998) "Musicking" concept, "emic" observations of stratification and essentialization culture in the School of Music (cf. Nettl, 1995), and situating themselves as participant observers in our semesterly Latin Dance Pachanga, a fun outdoor evening dance party at which we teach steps and coros (responsorial choruses) to all present.

MHL 140 is by no means a "World Music survey." Rather, I have targeted a few cultures for the specific musical challenges and competencies we can derive from them. These include South India, Arab, West African, Cuban, Javanese and Balinese gamelan. One of my aims throughout is to emphasize community (i.e., "community" with earlier times) through re-integration with musical practices that were once integral either in WEAM or its ancestors. The College Music Society Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major expresses this "conservative" philosophy, with which I largely agree (other than the use of the very controversial term "authentic," which I avoid):

...the longstanding conventional study of music in vogue through tertiary programs actually represents a radical departure from the European classical tradition. [The Task Force] proposes a return to the authentic [sic] roots of this heritage in a way that is relevant to our current musical lives. (2014, p. 12)

The concept of voice/body/dance integration permeates all sections. I allow no musical instruments ("your body is your ax"); instrumental technology is an obstacle to the basic music making I seek. The dance/music connection, fundamental to most musical traditions (in which musical competency often implied or implies dance competency), has greatly eroded in WEAM; many music majors are very self-conscious about their bodies, and about (non-alcoholically motivated) dancing. In our classes we dance (Cuban, Afro-Pop, Bollywood/Bhangra, Indonesian social styles) while clapping rhythms and singing (often complementary composite rhythmic patterns), thus both symbolically and concretely reintegrating the two sister arts, typically so separated nowadays.

The diversity of melody-type modes and intonations which characterized WEAM in its earliest forms largely disappeared by mid-eighteenth century. In Western, Central, and South Asia we can see art and religious modal musics descended from the same general sources as did WEAM. My students sing raga and microtonal maqam scales, learning (a sometimes reluctant lesson in cultural relativity) that these microtones, painful to freshman ears and music major minds long drilled in categorical "rightness" and "wrongness" of intonation, are as "right" as those few scales, in tempered tuning, to which they are accustomed. Normally, they combine musical challenges: multitasking, creating composite rhythmic sonic/rhythmic patterns is another of my typical modi operandi.

The complexity and diversity of meters once characterized WEAM in its early days, and influenced performance and compositional practices until the late Baroque tempered tuning standardization. I have students sing these scales while mnemonically reciting and beating out Indian tala and Arab iqa' additive metric patterns. We re-embrace the flexible, improvisational framework of the Baroque: the idea, still vital in the 19th century, that the "piece" is primarily a platform for the performer's co-creativity. They also learn that the "Golden Oldie" WEAM classics they know are not "received," Ur-texts, but rather contextually re-worked performance versions (Cook, 2001Cook, N. (2001). "Between Process and Product: Music and/as Performance." Music Theory Online 7(2), April.). Students learn (at a very "entry" level, to be sure) to create within the African-derived Cuban montuno structure (fixed group "responses" to improvised "calls"), experience the simultaneous group improvisation of Javanese gamelan garap (realization), and experience the rondo-like structure of Arab takht performances, in which fixed rondo-like themes alternate with improvised episodes.

My MHL 140 "Music as Culture" students are typically exposed to the preceding concepts, in these non-Western contexts, before experiencing them in the music theory and WEAM-oriented music history sequence classes that follow. This suits my aim of de-mystifying and "de-exceptionalizing" the WEAM tradition. Any ways that I can nudge the Western classical tradition (which was indeed my first "folk music," and which I love and revere) off its Olympian perch, and bring it (and my students) into active fellowship with the musical traditions of the past and present serves the goal which overarches all the preceding: that of creating meaningful community.

Curriculum, Context, and Community (Roger Mantie)

Curriculum scholars are wont to point out the Latin origins of the word curriculum, which is typically translated with reference to the running of a course (often by horses or chariots). As applied to learning and teaching, curriculum suggests that teachers are the designers of a “course” to be run, with students presumably changed as the result. Educationalists spend a lot of time debating this. So much time that an entire field of curriculum studies is devoted to exploring what should be taught and how it should be taught.

One of the perennial central issues in curriculum studies has to do with the generalizability or transferability of knowledge: can students apply what is learned in one context to a new context? Learning that fails to connect to prior learning was described by Alfred North Whitehead as “inert knowledge.” This situation often results in poor motivation (the need-to-know problem) and weak “real life” application. A related situation arises when existing knowledge is so strongly bound by context that learning intended to transfer does not.

This issue of the adaptability and application of knowledge is no stranger to musicians, of course. Most readers can likely bring to mind countless examples of musicians who are excellent stylist adaptors and boundary crossers and ones who are not, i.e., ones who are able to apply existing knowledge to new situations and contexts and ones who are not. One thinks of those who excel at both jazz and classical music (such as Wynton Marsalis), but also those who travel easily between all manner of musical styles and cultures. Mantle Hood’s bi-musicality is almost a given for musicians in the 21st century, many of whom are fluent in multiple genres of music making. One presumes that, rather than starting from scratch each time, the learning in one context aided (i.e., transferred to) learning in a new context.

Music making is only one aspect of having a career as a musician in the 21st century, however. My concern – one hopefully shared by others – is that the university music school curriculum too often fails to promote community engagement because so few schools of music require time spent in community “service learning” environments. One wonders how and why undergraduate music majors might “apply” their learning to the context of community in the 21st century when so little (if any) of their learning prior to graduation has involved time spent in “real world” contexts outside the practice room and rehearsal hall.

Arguably, the undergraduate curricula of those in music education and music therapy come closest to facilitating adaptability and application of knowledge, insofar as their degree programs typically involve a good deal of time spent in observation and practicum (i.e., “student” or “practice” teaching in the case of music education students). Unfortunately, from my point of view, music education “service learning” experiences are, almost without exception, spent entirely within K-12 settings. As a result, music education students come to university with a school music context in mind for music teaching-learning, they pass through a curriculum designed for a school music context, and they then proceed to work in a school music context. In my own experience teaching hundreds of school music teachers in online graduate courses where I gave a “community” assignment, I found most students had given very little thought to how their work might connect with, in, and through community. This situation has apparently changed little over the past 80-90 years. Commenting on a survey conducted in 1929-30, Agustus Zanzig remarked, “...in many of the 97 cities and towns visited by the writer for the purposes of the national survey, the school music teachers knew very little about musical activities going on in the community” (Zanzig, 1932, p. 287Zanzig, A. (1932). Music in American life: Present & future. London and New York: Oxford University Press.).

While some may choose to dispute the assertion, I argue that “community” does not yet adequately register as part of the curricular preparation of most undergraduate music majors, regardless of career track or path. In my department we have attempted to address this within the music education program by including “community leader” as one of the four core principles in our B.Mus.Ed. degree program. In order to avoid the pitfalls of “inert knowledge,” we have recently included this passage in the syllabi of applicable courses:

As central to the “community leader” principle of the undergraduate music education curriculum, each year throughout the music education major you will be required to have a minimum of 5 hours of observation in community leadership and socially engaged practice projects. At least half of those hours will be in community settings outside of schools.

Admittedly this is a very modest step. By incorporating an exposure component that involves a community placement, however, we (at my institution) are attempting to encourage the adaptability, application, and transfer of knowledge by ensuring that students have, at least minimally, experienced music learning, teaching, and performance in settings outside the practice room, rehearsal hall, or K-12 schooling as part of their curricular “course.”

My hope is that, in attempting to figure out ways to make music curricula of the future more relevant to the career dreams and aspirations of students, all university music schools will include some sort of “service,” “experiential,” “internship,” or “practicum” learning experiences that require students to spend time in the communities in which we are situated. Ideally, the distinctive flavors of every community will result in heterogeneous learning, rather than the homogeneity that has for too many years characterized music study in the United States.

Final Thoughts

Setting aside the thorny definitional matter of “musician,” the concept of preparation is fraught with the perils of the unanticipated and unforeseen. Few musicians (loosely defined) in the early 20th century likely anticipated the radical reorientation of musical production and consumption caused by mechanical reproduction and radio. Few musicians of the early 21st century likely anticipated the radical disruption caused by the mp3 and streaming. Prognosticators of the early 20th century, such as John Philip Sousa and Walter Benjamin, suggested that mechanical reproduction portended the end of the musician. The end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries have seen no end of similar stories about the “crisis” in classical music. And yet music lives on.

The five perspectives presented here are intended to contribute to the ongoing dialogue of what it means to “prepare musicians” within the norms, structures, and practices of music units in higher education. While some of what we have presented may appear on the surface to side with “contemporary” over “traditional” musical forms, reading our contributions in this way would be to miss the real point. It has not been our intention to present false hopes with the promise of some sort of shining new era. From our perspective it is not a matter of privileging one style or genre over the other, but engaging others within a genuine spirit of respect. In part this means recognizing digital musicianship as a reality, not a fad. If we are not to become marginalized within the academy and within society, we do need to engage students who have been traditionally underrepresented in our programs, and we do need to engage entrepreneurially with our communities to ensure that music making isn’t just an “academic” exercise. By thinking about music globally, hopefully we can encourage greater “transfer” among and between various musical practices, breaking down hierarchies and promoting genuine “engagement.” In our opinion, this is definitely a future for which to prepare.

References

Allsup, R. E. (2003). "Mutual learning and democratic action in instrumental music education". Journal of Research in Music Education, 51(1), 24-37.

Brown, Andrew. (2012). Sound Musicianship: Understanding the Crafts of Music. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Cook, N. (2001). "Between Process and Product: Music and/as Performance." Music Theory Online 7(2), April.

Covach, J. (2015a). “Rock Me, Maestro.” Chronicle of Higher Education (February 6), B14–15. Available at http://chronicle.com/article/Rock-Me-Maestro/151423/. Internet; accessed 11 October 2016.

Covach, J. (2015b). “Integrated Music Curriculum for the Bachelor of Arts/Bachelor of Music.” Available at http://www.rochester.edu/popmusic/curriculum/. Internet; accessed 11 October 2016.

Doyle, T. (2011). Learner centered teaching: Putting the research on learning into practice. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Elpus, K., & Abril, C. R. (2011). "High School Music Ensemble Students in the United States: A Demographic Profile". Journal of Research in Music Education, (2). 128.

Davis, S. G. & Blair, D. V. (2011). "Popular music in American teacher education: A glimpse into a secondary methods course". International Journal of Music Education, 29(2), 124-140.

Green, L. (2006). "Popular music education in and for itself, and for ‘other’ music: Current research in the classroom". International Journal of Music Education, 24(2), 101-118.

Hugill, Andrew. (2008). The Digital Musician. New York, NY: Routledge.

Karlsen, S. (2010). "BoomTown Music Education and the need for authenticity—informal learning put into practice in Swedish post-compulsory music education". British Journal of Music Education, 27(1), 35-46.

Lambert, N. M., & McCombs, B. L. (Eds.). (1998). How students learn. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Mark, M. L., & Gary, C. L. (2007). A history of American music education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

McPherson, G. E., and Hendricks, K. S. (2010). Students’ motivation to study music: The United States of America. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 201-213.

Nettl, B. (1995). Heartland excursions: Ethnomusicological reflections on schools of music. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Shuler, S. C. (2011). "Music Education for Life: Building Inclusive, Effective Twenty-First- Century Music Programs". Music Educators Journal, 98(1), 8-13. doi:10.1177/0027432111418748

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major. (2014). Transforming Music Study from its Foundations: A Manifesto for Progressive Change in the Preparation of Undergraduate Music Majors. College Music Society.

Vakeva, L. (2009). The world well lost, found: Reality and authenticity in Green’s ‘New Classroom Pedagogy’. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 8(2), 7-34. Retrieved from http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Vakeva8_2.pdf

Watson, Allan. (2015). Cultural production in and beyond the recording studio. New York, NY: Routledge.

Williams, D. (2014). Another Perspective: The iPad Is a REAL Musical Instrument. Music Educators Journal, 101(1), 93-98. doi:10.1177/0027432114540476

Zanzig, A. (1932). Music in American life: Present & future. London and New York: Oxford University Press.

1 For example, Pro Tools, an industry-standard digital audio workstation (DAW), debuted in 1991 at a cost of $6,000 (Watson, 2015, 22). Today, Avid's Pro Tools 12 can be downloaded by faculty and students for $299, while the stripped-down Pro Tools First is completely free.