The National Council of the Arts in Education is a federation of twenty-one national organizations* concerned with all the arts involved in our educational system at every level from kindergarten through college. It held its first national conference in September, 1962 at Lake Erie College, and has conducted six more, one each year until 1969. These conferences became a unique forum where the educational aspects of the several arts have been discussed in detail with emphasis upon the problems and aspirations common to them all. The need for such a forum has been demonstrated by the enthusiastic cooperation of the constituent societies as well as by the presence of a large group of distinguished consultants who have given generously of their time and wisdom to make these conferences both useful and stimulating. The proceedings of each have been published; the entire set furnishing an unusual record of insight and cooperation among the leading groups of teachers concerned with the arts in our society. The Council is now directing its energies toward the fulfillment of a new and more ambitious goal than any heretofore attempted.

The project here put forward by the National Council of the Arts in Education has been thought of, and planned for, over a considerable period of time. However, it was not possible to proceed very far with it until a generous grant from the Johnson Foundation of Racine, Wisconsin permitted N.C.A.I.E. to hold a working conference at their beautiful center, Wingspread, in August, 1969. At this conference, the Council, assisted by a distinguished group of consultants, was able to formulate the broad outlines of a plan to establish more perfectly, and more firmly, the place of the arts in American education. We hope that the support of the Johnson Foundation and our consultants will be justified in the end by the achievement of the goals of the project outlined in what follows.

I. INTRODUCTION

The Russian success with Sputnik I in October 1957 shocked the nation into a realization that its educational policies and performance in the sciences had been allowed to become seriously deficient. The result, as everyone knows, was a vast and powerful effort to remedy the defect, an effort which, at least in the field of space exploration, put men on the moon and brought them safely home again, one of the most prodigious technical feats in all of history. Is there any conceivable similar shock which could awaken our people to the lamentable state of the arts in that same educational process which was found so badly wanting in science? Is there any way to establish as a fact, the deep human necessity for significant exposure to the forces of the arts with sufficient cogency so that we would also be impelled in this area to make some great national effort leading to equally spectacular results?

It seems unlikely, simply because the force which thrust us forward in the days after Sputnik was that of fear, and disasters or inadequacies in the arts do not inspire fear, whatever other emotions they may arouse. And yet, in recent years, there has been increasing concern amounting now to a definite anxiety about the quality of our national life. While we seem to multiply material conveniences at the same rate as the population, we are heedless of the true values of our acts, or the real worth of the devices on which we are spending the colossal sums of money we are earning. The crisis in our spiritual lives is slower in becoming distinct, but the gradual outlines of it are now clear, and we may no longer postpone dealing with the spectre taking shape before us.

The attitudes which earlier societies, even quite primitive ones, have adopted toward the several arts has furnished us with one of the few really reliable means we have by which to measure the value of that society in terms of human life. There never has been a great society since history began which was not also great in its capacity to create artistically. It is not possible for America to suppose she can provide the full, rewarding life for her people that a high culture demands of her without paying close attention to the relation her people have to architecture, dance, theatre, painting, writing, the film and all the rest. We behave too often as if plumbing, guns, the digestive tract, or supersonic speeds were the locations of the true human interests of men. But we know better, and the time has come now to admit that we do.

No one should expect that massive new attention to the arts would usher in the millennium of peace on earth and good will toward men; what it would do is to supply for the first time in our history the resources to satisfy one of the most deeply seated of human needs—the need to make and enjoy the arts. It is not that we are more virtuous if we play the oboe or take delight in a modern dance performance; it is simply that we are fulfilled in certain ways by these pursuits, and if we are not thus fulfilled, we are incomplete, even frustrated, and by that incompleteness and frustration, seriously flawed as individuals and as a society. What are our present values? We want to make enough money to be "comfortable," we want to stay healthy, and we want to stay free. On top of this, some of us want to see to it that we are none of us hungry and all of us supplied with the dignity which is our right as human beings. But surely we cannot feel that our desires for the good life stop there? Are we not willing to spend the comparative pittance it would take to give all of us during the years of our learning the vastly rewarding dimension the arts can supply to our lives? People suffering from certain vitamin and chemical deficiencies don't know really that anything is wrong with them except that they feel somehow torpid and dull. As a nation we are torpid and dull in the life we lead in art, suffering for the lack of what real support for them could do for us, but as yet we don't know that there is really anything wrong. As of now the fishing rod and the TV screen are all the cultural aids most of us desire. But they are not enough; not in a decently affluent society.

In this, the second half of the twentieth century, we who are professionally devoted to the educational aspects of the arts, reassert the existence of that necessity known by all societies throughout history for expression by means of the arts, and a new necessity, born of our wealth, to make a fair exposure to such artistic expression the right of everyone both during the years of his education and thereafter.

Our nation already partially admits both of these, as is attested by the evidence of buildings to house the arts, societies and groups to perform them, some private (but pitifully little public) support to sustain them, and at least some schools in which some of them are more or less well taught. And yet the United States is still far from reaching a satisfactory determination of their place or true importance in our national life.

The present concern of the National Council of the Arts in Education in proposing this project lies in its basic desire to establish once and for all a solid and honorific place for the arts in our educational plans, in our curricula, and in the very architecture of our schools and colleges.

Just as we condemn verbal illiteracy as unworthy of a nation unreservedly committed to universal education, so also we condemn an illiteracy of the senses and imagination which, whether realized or unsuspected, seriously impairs the life styles of a majority of our people. We maintain that the study and practice of the arts by anyone, gifted or not, is, in and of itself, valuable; quite as valuable as the study and practice of other disciplines we already unthinkingly accept as necessary to even a minimal education.

The nature and practice of the traditional arts are changing rapidly in the late twentieth century so it is imperative that, from time to time, we assess our current educational practice in regard to them, as well as the newer media such as film, radio, television, and others more modern still. If all the arts are ever to take their place in the curricula of our schools and colleges, we will have to learn more precisely what the students themselves want, how to train them so they can adequately serve the expressive purposes of each rising generation, and what emphasis to place on the power of feeling in our instruction, functioning as it does in an environment heavily weighted on the side of science and technology.

It is our desire to contribute what we can to sound thinking on these subjects. Our plan is to assess the present state of all the arts at all levels of the educational process, and then employ all possible means by which their essential role in it can be more soundly established. The project, unique both in scope and goals, is sponsored by the only body in the United States already concerned with all the arts in all formal educational systems, a body thus uniquely fitted to furnish the sound appraisal required as well as suggest useful models for improving existing conditions. The first stage of the project will establish a clear contemporary picture of the present status of the arts in our educational process, while at the same time providing a mass of accurate, persuasive data by which progressive policies can be shaped in the future. The second stage will provide and apply the techniques necessary to arouse public interest and support among those social groups capable of altering present practices, so that proper room can be made for a true exposure to the arts as an essential part of any intelligent preparation for the good life in the century ahead.

II. CONCERNS

The basic concerns of the project can well be expressed in terms of a series of oppositions now apparent in our educational programs:

- The traditional notion of the arts as the special possession and responsibility of the upper socioeconomic levels of our society, as against the idea of an artistic democracy in which each individual, community, and group of communities, contributes to, and benefits from, the national culture.

- The imperative to achieve excellence in the arts set against the need to engage all people in some form of artistic experience.

- The notion of presenting the arts in the schools as a form of "audience" enjoyment by way of critical understanding, opposed to the idea that everyone should himself learn the discipline of aesthetic form and executive proficiency in at least one art, possibly in some way that will enable him to approach other art forms with the same knowledge of aesthetic discipline.

- The concept of the arts as a form of recreation, as against the idea of them as the cutting edge of our understanding of ourselves and of the world, and our awareness of the artist as a challenger of accepted values.

- The traditional notion that music and the visual arts are sufficient for arts programs in general education, set against the idea of making available instruction in dance, theatre, or the new media such as photography, cinema, radio, and television.

- The widespread belief that the arts in education are frills around a more significant core of studies stressing languages, factual knowledge, scientific rationality, and technological skills, as opposed to the idea that a discipline of aesthetic form has a necessary place among the main disciplines of thought and action known to man. (This opposition leads inevitably to the idea that the arts belong in service departments, should be dealt with outside regular school hours, etc.)

- The traditional practice of having the classroom teacher provide instruction in the arts, contrasted with the demand that they be taught only by specialists possessing proper knowledge and experience.

- The traditional notion that education in the arts need not proceed beyond the eighth grade, as against the idea that aesthetic education, by way of a well-planned and executed program, should extend through all levels and even beyond into adult education.

- The current meagre allocation of resources to arts education programs coupled with a severe shortage of personnel, as opposed to the need for sufficient new equipment, adequate professional space, and larger numbers of well-qualified instructors.

- The practice of conducting education in the arts in terms of traditional theatre, ballet, symphony orchestras, operas, museums, and art galleries, as against the challenges of new content and new art forms now appearing everywhere.

- The intense preoccupation among art educators with the individual, against the need to come to terms with the demands of the larger social systems in which we actually live.

- The traditional practice of imposing curricula uniformly, as against the desire for students for a voice in determining what and how they are taught.

If real progress toward even a partial resolution of these oppositions could be effected by means of this project, it would have served a vital purpose in the improvement of our entire educational program.

III. THE NATURE OF THE PROJECT

A. PHASE ONE.

In this, the first part of the project, the endeavor will be to acquire a quantity of well-ordered, wide-ranging expert information and opinion dealing with present problems and future possibilities for all the arts in a general, non-professional education. This material will:

- Examine the role of the arts in the entire educational process.

- Propose ways of meeting the demands on art education posed by contemporary social pressures and by new forms and content in the arts themselves. It will give consideration to the requirements of different sectors of society, different levels of education, different types of student interest, and new approaches to pedagogy.

- Indicate effective means of reaching the several sectors of society most immediately concerned with educational policy, with a view to explaining to each the necessary conditions for successful art instruction in our schools and colleges.

- Assess new curricular models in the arts and suggest, where appropriate, means of introducing them into our national practice.

- Explain the relevance of the arts to the teaching of other disciplines.

- Review the direction and accomplishments of current research in the field of education in the arts.

In interpreting this material, the project would consider all of the arts on each of four educational levels, paying particular attention to the means of transition from one level to another:

- Preschool, kindergarten, and the eight grades.

- High School.

- Education beyond the high school but only up to graduate education.

- Adult and continuing education.

B. PHASE TWO.

In the second part of the project, the material gathered and interpreted in Phase One will be used in a professional campaign to bring the relevant parts of it to each of a variety of social groups whose attitudes condition the acceptance of the arts as a legitimate part of a general education, and, in large measure, create the climate in which they operate socially. As skillful use as possible would be made of all appropriate media within the limits of the budget available. Among the specific groups to be reached would be the following:

- Parents; and through them the public in general.

- School boards and local educational administrative personnel.

- Federal, State, and local officials and agencies that deal with education and also the arts.

- National and state legislators.

- Major sources of philanthropy such as industry, business, labor unions, and foundations.

- The professions such as law, medicine, the ministry, etc.

- Students.

- Practitioners of the various arts.

- Teachers of all kinds.

Possible by-products of the project might be: the investigation into the feasibility of establishing a high-level Commission on the Arts in Education, a body to coordinate the work of all national groups having similar spheres of interest and influence; and the exploration of ways by which the National Council of the Arts in Education might cooperate more effectively with the Associated Councils of the Arts.

IV. PROCEDURES

While it is not possible, or even advisable, to describe all the procedures involved in this project before it begins, the following is a statement of the broad plans for its staffing and operation. By intent, much latitude has been left to the Director and Campaign Manager.

Staff. The basic staff will not be large because much of the work will be done on a contractual basis. The tenure of the Director and Campaign Manager are indicated on the Budget. In over-all charge for the first two years will be the Project Director who will be assisted by an Associate Director. Midway in the second year these two will be joined by the Campaign Manager. The Office Manager will be in operational charge of the Project Office and will be assisted by a Clerk-Stenographer-Secretary.

Services. While the project will use only a small operational staff, it is proposed to make extensive use of contracted services. These will be of three major classes: Research Consultants, Writers of Working and Position Papers, and Synthesizing Writers and Media Specialists. Thus specific information will be obtained from commissioned research as needed, working papers and even articles will be written especially for the project by writers engaged for the purpose, and media presentation will also be prepared in similar fashion. The Associate Director will be in charge of writing done for the project and will serve as a sort of general editor. All final publication will be done under his supervision.

Conferences. A major device for acquiring information and opinion throughout Phase One of the project will be the holding of conferences. These will be of two major kinds: routine and special. Routine conferences will be the regular meetings of the Board of N.C.A.I.E. as well as the summer conferences such as those held in the past to discuss special topics. The topic during the years of the project will be that of the enterprise itself. It will be here that the views of constituent societies will be freely set forth and discussed, and here that special matters can be looked into such as the needs and opinions of minority groups, national matters, and other broad issues vital to the purposes of the eventual campaign. Special conferences will be regional for the most part so that the conditions in all major areas of the country can be properly assessed. In addition, such conferences may explore certain problems in depth, or in different social environments (rural vs. suburban vs. center-city, for example). The Director will have the major responsibility in this area.

In addition to conferences organized by the project, it is planned to make extensive use of conferences put on by other groups having interests in this area as well as the annual meetings of all constituent societies. The staff will attend as many of these as circumstances permit and will endeavor to have some discussion of Arts/Worth placed on the program.

Steering Committee. The Steering Committee will be the advisory body of N.C.A.I.E. most closely and continuously associated with the project through all three years. This committee will serve as liaison with the Board of N.C.A.I.E. as well as being available for consultation and advice as needed. It is expected that it will need to meet quite frequently with the staff.

Campaign Manager. This position indicates that Phase Two of the project will require expert professional direction since the use of media to influence opinion requires certain skills which the staff would not normally be expected to possess. The success of the campaign to persuade America that we must reset the arts higher on our scale of educational priorities is really the main hope of the whole project and will be the responsibility of this member of the staff. Just how the campaign will be managed cannot be forecast at the outset since it will depend greatly on the budget available and the political and social climate of the country in 1972.

Bibliography. The assembling of a research bibliography on the arts in education has already been begun and will be an important as well as useful by product of Arts/Worth. Once in existence, it would be important to insure its maintenance for general reference in the field.

Travel. It is assumed that the staff, especially the Director and Associate Director will travel extensively, acting as the chief investigators for the project as well as the coordinators for all its research activities.

Policy. The nature of the final campaign will be the product of the investigation and coordination that will precede it. The views of the constituent societies, their knowledge, and their aims will play the decisive role in the formulation of the substance of whatever message is brought to the American people. Hopefully, there will be both consensus and disagreement, innovation and rededication to proven practice, but basic to all else will be the conviction that the arts are a necessary element in any proper general education as we approach the end of the Twentieth Century. Every effort will be made to seek out and examine original or unusual programs, exceptionally supportive environments, helpful public, legislative, commercial, and intellectual attitudes toward the use of art in our schools and colleges, and indeed all facts, trends, and theories which will serve to persuade people as they have never been persuaded before that all the arts are educationally significant. The publications coming out of the project will, hopefully, serve as a record of what was found out, a resource for future action and planning, as well as forming a part of the campaign itself.

V. DEVELOPMENT OF THE PROJECT

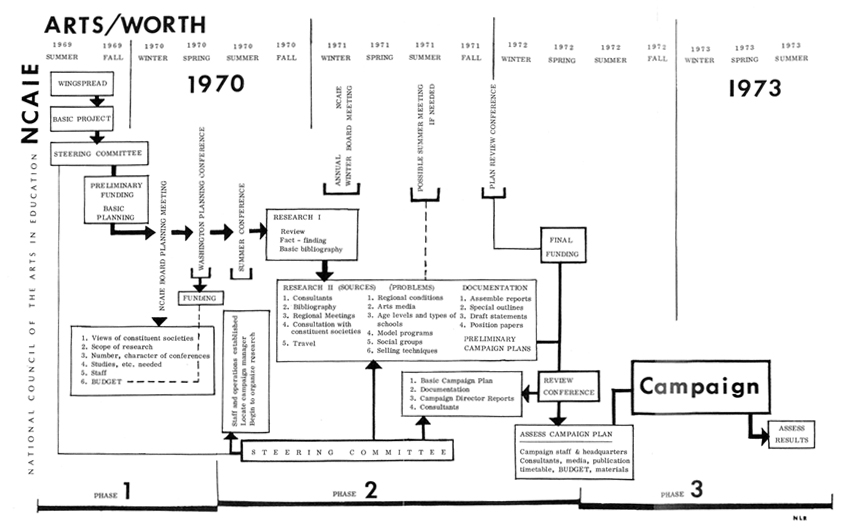

(The chart below gives this development in schematic form.)

Spring 1970. By this time the general nature of the project has been blocked out and approved. The Project Director has been appointed, a preliminary Chairman's Grant has been received from the National Endowment for the Humanities with money transferred from the U.S. Office of Education, and the Washington Planning Conference has been called to assist with funding and other plans. Following this, the project will be whipped into final shape for submission and plans for the Summer Conference will be carried forward.

Summer 1970. It is assumed that funding for the first year's operation at least has been assured by July 1, 1970. During this time the staff will be recruited and an office secured. Meanwhile a double conference will be held at some appropriate location. Partly this will be for planning purposes and consultation with constituent society delegates, but even more importantly it will be a consultative conference with representatives from minority and disadvantaged groups to seek their help and counsel on this part of the large campaign, a very significant part of which will obviously have to deal with the numerous and great problems in this sector.

Fall 1970. Office and staff assembled. Research begun as outlined in Section IV above. Start of search for Campaign Manager.

Winter 1971. Winter meeting, Board of Directors of N.C.A.I.E. Research continues.

Spring 1971. Research.

Summer 1971. Research. Summer N.C.A.I.E. Consultative Conference. Discuss campaign budget.

Fall 1971. Research. Start of assembly of all review conference material. General advanced preparation. Campaign Manager should be appointed by this time.

Winter 1971. Research. Final preparations for review conference. All documents, position papers, etc., circulated in advance.

Spring 1972. FINAL REVIEW CONFERENCE. Full discussion of resource material and campaign plans. Directions from Campaign Manager.

Summer 1972. Preparations for start of campaign in fall.

Fall 1972. CAMPAIGN.

Winter 1972. CAMPAIGN.

Spring 1973. CAMPAIGN.

Summer 1973. Assessment Conference. Plans for future action.

*Member Organizations: American Dance Guild, American Educational Theatre Association, American Musicological Society, American Society for Aesthetics, Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, College Art Association of America, College Music Society, Committee on Research in Dance, Dance Notation Bureau, Music Educators National Conference, Music Teachers National Association, National Art Education Association, National Association of Schools of Art, National Association of Schools of Music, National Council on Education in the Ceramic Arts, National Dance Division of AAHPER, National Theatre Conference, Society for Cinema Studies, Society for Ethnomusicology, United States Institute for Theatre Technology, University Film Association.