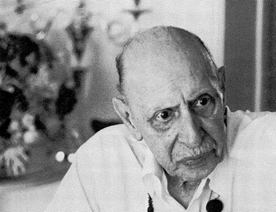

Bobby Klein photo—Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

"I would warn young composers too, Americans especially,

against university teaching. . . ."Igor Stravinsky

Editor's Foreword

Even a glance at the twenty-three essays that follow will suffice to show that a highly remarkable survey is before us. A representative cross-section of America's important composers who are (or have been) affiliated with the academic milieu has responded to a question of profound implications. The question began some dozen years ago when Robert Craft asked Igor Stravinsky what cautions he would offer to young composers. Stravinsky answered with such formidable candor as to discourage any but the most gifted and stubborn from siding with the Muse. (The Stravinsky advice is reprinted below.) While we have no way of estimating how many talents of greater or lesser genius decided then and there to switch to piano, theory, musicology, or English literature, it is readily apparent that some strong wills did survive the negative influence and went on to become composers of stature. That such a number of them, moreover, chose to combine composing with teaching, in the face of stern admonition against the dangers of academia, has without question been of untold significance to our musical culture since 1959, on and off campus.

It occurred to us to inquire about their health in 1970, and especially about their reactions to Stravinsky's strictures after a decade. Some four-dozen letters were dispatched to established composers whose artistic careers have been notably successful on campus, and to a few whose eventual quitting of academic life has brought them similar success. Twenty-six responded with enthusiasm to the survey which evidently touched a reactive nerve. Three of them were compelled to withdraw at the last moment because of the turmoil of May '70, business trips to Europe, and more congenial (musical) commissions coming due.

We can only be very grateful for the overwhelming response which gives us such an overall insight into the composer's role in academia at the moment when it is being continually debated by certain administrators on one hand, and by pedants on the other. Perhaps more important, and less expectedly, we are also given some superb insights into the composer's milieu, his thought processes and style, his concerns about artistic and worldly affairs, his human nature, to name only a few observations. It will be seen that theorist William Mitchell's comment in his Prologue, that Stravinsky's writings are much like his music, is perhaps equally applicable to every composer here.

It would be foolish to attempt to extract the essence of the twenty-three "Reflections on a Theme of Stravinsky," other than to note that a pervading idea seems to suggest that the composer in academia is as profoundly concerned as his academic colleagues, and perhaps more so, about the critical state of our culture. Not all would agree with Babbitt's view that "the question involves nothing less than the very survival of serious compositional activity," or Shifrin's "The university is the last open city;" but few would seem to disagree with Trimble's "There is still a total and devastating split between the world of the public concert-hall and the world of the university," to which he adds, "For myself, I have always liked teaching."

IGOR STRAVINSKY AND ROBERT CRAFT

Advice to Young Composers1

R.C. Will you offer any cautions to young composers?

I.S. A composer is or isn't; he cannot learn to acquire the gift that makes him one, and whether he has it or not, in either case, he will not need anything I can tell him. The composer will know that he is one if composition creates exact appetites in him and if in satisfying them he is aware of their exact limits. Similarly, he will know he is not one if he has only a "desire to compose" or "wish to express himself in music." These appetites determine weight and size. They are more than manifestations of personality, are in fact indispensable human measurements. In much new music, however, we do not feel these dimensions, which is why it seems to "flee music," to touch it and rush away, like the mujik who, when asked what he would do if he was made Tsar, said, "I would steal one hundred roubles and run as fast as I can."

I would warn young composers too, Americans especially, against university teaching. However pleasant and profitable to teach counterpoint at a rich American Gymnasium like Smith or Vassar, I am not sure that that is the right background for a composer. The numerous young people on university faculties who write music and who fail to develop into composers cannot blame their university careers, of course, and there is no pattern for the real composer, anyway. The point is, however, that teaching is academic (Webster: "Literary . . . rather than technical or professional . . . Conforming to . . . rules . . . conventional . . . Theoretical and not expected to produce . . . a practical result"2), which means that it may not be the right contrast for a composer's noncomposing time; The real composer thinks about his work the whole time; he is not always conscious of this but he is aware of it later, when he suddenly knows what he will do.

1From Conversations with Igor Stravinsky by Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Co., 1959), pp. 153-154. Reprinted by permission of Virginia Rice, Agent, Copyright 1958, 1959 by Igor Stravinsky.

2Editor's Note: The definition of "academic" seems to be extracted from Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary (Springfield, Mass.: G. & C. Merriam Co., 1959), wherein the full definition reads as follows: "1. Pertaining or belonging to an academy, college, or university, or to colleges, etc. 2. Literary, classical, or liberal, rather than technical or professional; as, an academic course. 3. Conforming to scholastic traditions or rules; conventional; as, academic verse. 4. Theoretical and not expected to produce a practical result; as, an academic discussion.—Syn. Pedantic, bookish, scholastic: theoretical, speculative."

WILLIAM J. MITCHELL

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK, BINGHAMTON

Prologue

Igor Stravinsky's writings are much like his music—which is not a surprising statement. Both, however, rarely lack a stimulating provocativeness and insightful dartings, along with mystical, often mystifying flights of the untrammeled imagination. The brief passage under consideration, from Conversations, is no exception. In accepting an invitation to respond to it as a non-composing theorist, my first condition was that I be spared from reading the responses of my composing colleagues and friends, some of whom have at one time or another been my students. Not that I want to remain aloof from their reactions. Far from it. Those listed, however, include many of such overweening conviction that I was fearful that my contribution might in the end be reduced to a mere, "Me too."

The crux of Stravinsky's "Advice to Young Composers" will be regarded by many as the avoidance of university teaching, which he could describe in 1959, the days preceding the Age of Protest and Inflation, as "pleasant and profitable." It is no longer either of these, yet it remains a way of life for many, as compelling and inescapable as composition to the composer who "will know that he is one if composition [substitute, teaching] creates exact appetites in him and if in satisfying them he is aware of their exact limits."

The points to be emphasized are several.

First: In the students' and harried administrators' views good, indifferent, and poor teachers exist in various combinations. These combinations are evident regardless of whether the teacher is a composer, performer, theorist, or scholar. They are formed less by specific callings outside the classroom than by an enduring interest in students, the institution, the subject matter, and an ability to communicate.

Second: The number of productive composers who are residents of so many campuses suggests strongly that the university or college can not be held responsible, or let us say totally responsible for any individual's falling off in productivity. The artistic quality of the works composed is dependent on critical assessment, however, rather than the waving of college colors. Certainly, within my experience, I have seen composers thrive both on and off the campus, but the tonic benefits of enthusiastic young university audiences, both pro and con, are not to be underestimated.

Third: "Academic" is what you, not Webster's, make of it. Dictionaries, good ones, have historical, not eternal validity. In this limited sense they serve a highly important function, but it should not be regarded as overriding. Academic, in its current sense, had better mean, simply, those things that happen, educationally, in an academy, which by extension includes Stravinsky's "Gymnasium" and the more usual designations, here, of College and University. It is up to the teacher (composer, etc.) to redefine the term constantly in its ancient or more relevant modern meaning.

JON APPLETON

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

"If teaching prevented me from working to capacity, I would do something else."

The following chart is my answer to the old man whose music I love but who has never learned to mind his own business.

| Year | Occupation | Hours Spent Composing Per Day |

|||

| 1945 | Student, first grade | .2 | |||

| 1946 | Student, second grade | .3 | |||

| 1947 | Student, third grade | .4 | |||

| 1948 | Student, fourth grade | .5 | |||

| 1949 | Student, fifth grade | .7 | |||

| 1950 | Student, sixth grade | .4 | |||

| 1951 | Student, seventh grade | .2 | |||

| 1952 | Student, eighth grade | .1 | |||

| 1953 | Student, ninth grade | 0 | |||

| 1954 | Student, tenth grade | 0 | |||

| 1955 | Student, eleventh grade | 0 | |||

| 1956 | Student, twelfth grade | .2 | |||

| 1957 | Student, college freshman | 1.0 | |||

| 1958 | Student, college sophomore | 1.3 | |||

| 1959 | Student, college junior | 1.5 | |||

| 1960 | Student, college senior | 1.6 | |||

| 1961 | Assistant buyer, large department store | 1.5 | |||

| 1962 | Music teacher, small prep school | 2.0 | |||

| 1963 | Graduate student in music | 3.0 | |||

| 1964 | Graduate student in music | 3.0 | |||

| 1965 | Graduate student in music | 2.5 | |||

| 1966 | Music teacher, large university | 2.0 | |||

| 1967 | Music teacher, small college | 2.4 | |||

| 1968 | Music teacher, small college | 3.0 | |||

| 1969 | Music teacher, small college | 3.0 | |||

| 1970 | Music teacher, small college | 3.0 | |||

I have rarely enjoyed composing for myself without any opportunity to have my work heard. My third, fourth, and fifth grade teachers encouraged me to compose for the weekly assembly. While an undergraduate my fellow students thought I was a composer and this made me think so too and to fulfill our expectations I composed more often. As a graduate student in composition I composed as often as I was interested in my own music and then listened to the music of others, dead and alive. My slightly reduced output in 1965 was due to the limited hours available in an electronic music studio. My steady output over the last few years has been due to requests for my music from people who give concerts and from a record company. I have always thought of myself as a composer although I know some composers spend many more hours per day. If teaching, or any other activity, prevented me from working to capacity I would do something else.

MILTON BABBITT

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

"It is not only because the university is our sole hope that it is our best hope."

One of the apparent, if secondary, advantages of the academic composer is his ability to identify and—therefore—dismiss an argumentum ad verecundiam. And neither Stravinsky's authority as a composer, Craft's as an interlocutor, nor appeals to the methodological authority of a lexicographer who dares oppose the "theoretical" to the "practical," dares invoke the term "rules" with equivocal evocations of the normatively "conventional," possibly can be construed as providing authority for statements about the American university, or the American composer in the American university. The further counsel that certain colleges are perhaps excessively seductive for the composer, or that the composer is less able to think of his own music while teaching counterpoint than while conducting Tschaikovsky, I leave for examination by those of my colleagues who suffer such pedagogical distresses, since I teach in a predominantly male institution, and my music has counterpoint.

Nevertheless, Stravinsky and Craft notwithstanding, the question posed is a critical one, so critical that it involves, simply and surely, nothing less than the very survival of serious compositional activity (and, universities being as numerous and tolerant as they are, one needn't be even too serious in the application of the term "serious.") For a necessary condition of such survival is the corporeal and professional survival of the composer, which is provided—for all but the extra-musically fortunate few—only by the university. And let no one of academic pedigree suggest, tautologically or circularly, that such musics—therefore—have no right to survive; "therefore," because they do not have a quantitatively adequate audience materially to support them; rather, let someone presume to demonstrate where in the music this unworthiness resides, for the allegation that our music has but a tiny audience, like the assertion that Schoenberg's music—in sixty years—has not found a "wide" audience, is not a statement about the musics, but about the audiences.

But it is not only because the university is our sole hope that it is our best hope. It alone permits us and equips us fully to engage those unprecedently deep and intricate questions of musical creation in our time, and be obliged to face those questions as they are variously posed by the unprecedented young composers which our musical time has created. It obliges us to consider what music has been, and—consequently—is and may become, to the end of one's daring to attempt to make it as much as it can be. It provides us with a community, a select community of colleagues, rather than competitors.

This last may appear to lend support to the insinuation that university composers "write for each other." The intimation that an educated composer makes his compositional decisions and choices by consulting an external or internalized game matrix for an optimum strategy for impressing his peers and academic superiors is, I trust, preposterous, but no more preposterous than the associated intimation that, if a composer—deliberately or unawarely—were to address his music to an audience, it would be less moral and relevant for that audience to consist of his peers than of nonacademicians of unknown capacities and questionable authority.

I am told that it has been suggested that university composers write music about which they can most successfully talk. To this accusation I can but claim innocence on the evidence of lack of success. I never have lectured on my music in the classrooms of Princeton, and—although I have talked in many places of many things, including the music of Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Varèse, Webern, Sessions, and Carter, rarely have I been permitted to speak of my own compositions. Even so, if discourse about a composition is assumed to convey accurately the structure of the composition, the simplest music to talk about is the simplest music, the writing of which some of us have never been accused. But, since so much of what passes for discourse on music (be it by commercial, literary, or academic journalists) bears no confirmable relation—beyond that of obfuscation—to any music, what is said about a work can be arrived at quite independently of the work, and—therefore—one can compose what he likes and yet say whatever his preferred audience likes.

But, it is true that the university composer is likely to feel or must feel a particular obligation to verbal expression, as a teacher, a musical citizen, and a member of intellectual society. At this moment our university colleagues outside of music are far more likely to respond to the sense of our words about music than to the sound of our music. For, although the university is the best of all available worlds, it could be much, much better for the composer. And while it is imperative to avoid that current error that because things could be better they couldn't be worse, it is urgent to identify the ways in which things could be better, must be made better. And the university's deadly deficiencies simply are the extent to which it reflects the "real world" outside the university. I have discussed and documented elsewhere the outrageous presumptions of scientists, aestheticians, cultural historians, and—even—music historians with regard to contemporary composition and, just, music. The cumulative, or subtractive, perpetuation of musical ignorance up through university faculties and administrations imposes the notorious double standards upon the university composer. For the conditions necessary for the creator of serious music are not essentially, different from those of—say—the creative philosopher or mathematician; it is not that the fields are similar, but that the practical issues are identical. To the extent to which the composer's professional needs are not accommodated by and in the university, and they are not with regard to publication of his music, preparation of materials, performance and recording (indeed, all the modes of professional communication with—at least—his colleagues), to that extent the composer is driven out of the university to dependency upon recording executives, commercial publishers, and—even—journalists, who simply do not have the right (in the sense that, under rational conditions, rights derive from pertinent competences) to decide what compositions shall be permitted to become known, and—thereby—perhaps to survive. The trouble with the university is not that it has protected the composer from the confusions, demands, and coercions of the "real world;" the trouble is that it has not. Should the professional needs of the composer ever be so satisfied in the university, and yet there remain composers whose psychological needs and musical aspirations are not, then the university will have done the further service of segregating those who confuse celebrity with achievement from those who do not.

WILLIAM BERGSMA

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

"Under which condottiere do you travel, in a troubled time?"

Writing from Italy, may I rephrase your question? as: under which condottiere do you travel, in a troubled time?

We always have the establishment—Church, State, Patron—sometimes good, sometimes not, now not. We now have Foundations, on an on-and-off basis, and Universities. Sometimes we have the Theater (for which read box-office, with or without subsidy). We should ask Stravinsky about this: how good an influence, in 1926, was the Ballets-Russes on the composer of The Rite of Spring?

In my experience, composers themselves pay for the subsidies accorded them. Someone commissions me, for $2,500, to write a piece it will take me a year to write. Who is the patron, in economic terms? I am.

If a composer is to pay for his own writing time, he must make the best bargain he can with the surrounding powers, for which none but himself has the right to reproach him.

As I see the picture in the United States in 1970, there are perhaps sixteen universities at which artistic circumstances are such that a working composer might feel justified in risking employment.

Stravinsky's concern about conservative formality is out of date. Sometime—it will take more than 600 words—I would like to dissect the current academic blight. For the present, let me define the enemy in six words: music to give a lecture on.

HOWARD BOATWRIGHT

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY

"The 'real composer' always manages to find the necessary time to compose."

Stravinsky warns young composers especially against university teaching, but he weakens the force of his warning to the point that one need not take it very seriously. First of all, he says a composer either is or isn't one. Further, he says there is no pattern for the career of the "real composer." Those who know they are real composers, need not take fright at such a warning; for others, it would make no difference whether they were non-composers in universities or outside.

Just as there is no one pattern for the development of a composer, there is no one best way of spending non-composing time. There are those who find involvement with other music (playing, conducting) the best counterforce (Bartók, Stravinsky himself). There are those who prefer an entirely non-musical activity (Ives, Schuman). Undoubtedly there are also those to whom teaching theory, even of a conventional sort, is a satisfying contrast to composition (Schoenberg, Piston); those to whom a class is a stimulus in the ongoing development of their own compositional techniques (Babbitt, Messiaen); and those who do not find the teaching of any sort of theory, conventional or new, in itself an obstacle to their own work (Hindemith, Sessions).

There has never been a time when composers have not had to do something other than write music in order to exist in their particular social and economic settings. Even royal patronage of the past usually involved the composer's services as a performer or conductor. In their later years, some nineteenth-century composers reached a degree of freedom from patronage and earned a sufficient amount from composing to make ends meet (Brahms, Dvořák). A few composers other than Stravinsky manage it now (Britten, Copland). In rare cases, independent wealth has eliminated the economic factor (Mendelssohn, a banker's son; Vaughan Williams, a descendent of Josiah Wedgewood). But for most composers the economic factor has been crucial, and it is the one which has turned present day composers toward the university.

The university is no more (perhaps less) demanding than any of the other external agents which have in the past demanded and consumed that part of the composer's life which Stravinsky describes as "noncomposing" time. The real struggle is for enough (but not too much) "composing time" to realize the thoughts which gestate during the non-composing hours. Stravinsky's fear that these hours may not be spent properly in academic work may result from the fact that he himself never had to use his own non-composing hours that way. If he had been forced to teach (as were Hindemith and Schoenberg during the Forties), his development during that period would probably have been very much the same. The "real composer" always manages to find the necessary time to compose, and somehow to balance his life, no matter what demands are made on his non-composing time. In fact, this is one of the traits by which we can recognize him.

ELLIOTT CARTER

WACCABUC, NEW YORK

"The composer is a university commodity."

The effect of teaching in universities by young composers, on them and their works and on the public and music profession will have to go through many stages and be reconsidered many times before it can be evaluated, if it ever can. Certainly between 1959 when Stravinsky wrote his advice and 1969 when I write this, so much has happened in American society and its relation to education and so much within the field of music that one hesitates to give any general answer at all—music is not what it was in 1959—and neither are universities.

One can, now, as then, list the goods and bads only and not predict. But there is one fundamental question—the one of education itself as a pattern which indicates that it could be an unhealthy situation for composers to be too much involved with education, especially in a university. For the age level of students, and their preparation is always the same in each new class, from year to year, while the composer changes and develops and naturally grows older—and more experienced in the ways of his own generation (often thought nowadays to be irrelevant to the next generation). This constant rebeginning for the sake of the young is not always the best atmosphere for a composer to develop in.

Also the fact that the university is a passing stage, a preparation (?), a training (?) for life outside of the university for students, means that the academic society itself should have this as its goal and not become too much involved with itself—which it very often tends to do, and therefore a composer living in this atmosphere could lose the sense of writing for the outer society which he should be helping to develop. One could imagine students today being very critical of many of the more recondite activities of American graduate schools, including music schools.

To come down to more precise matters:

BAD: The American composer, like his colleagues on university faculties, tends to be treated as a commodity with these tangible assets: reputation (the kind formed by American publicity, or taken up by American publicity from foreign cultural propaganda), which the university does little to help him to increase once engaged, and hence which often deteriorates during the teaching years; verbal articulateness (not characteristic of composers qua composers, although sometimes found even in good ones); new ideas about music techniques, analysis, theory, and teaching techniques (preferably those that will evoke publicity—now computer methods, etc.); closeness to the "new" trends, as defined, of course, by the news media.

While one can have no objection to having all of these taught in a university (except on the basis of the quick obsolescence of most of the "new" in art), the emphasis on these is hardly conducive to the composer's own development. For the composer's own work becomes of small importance to his department (which explains the American Society of University Composers) unless it can get important write-ups in the news, or unless the composer is willing to tear his own pieces apart, explain them in detail and show his students how to do it in a few easy lessons. Thus his work is of little importance, so it often seems, unless it can be transformed into the tangible assets of "reputation" or "articulateness."

BAD: Since composers seem to be regarded as immediate (and often dispensable) commodities both by university management, by most of his students and even by his departmental colleagues (for the most part), he becomes part of a competitive market and he cannot help but be aware that there is a constant look-out for others with greater assets, especially reputation. Since universities usually tend to downgrade composers' reputations, once employed by them, there is a look-out for those previously not associated with U.S. universities—composers whose reputations are made and sustained by effective cultural propaganda from the country of their origin, not available to American composers. Many of these from other countries continue to profit by the cultural propaganda of their country even while employed here, thus putting their American colleagues in the shade.

Naturally, one would not want to eliminate the important thought and contribution of non-Americans to our culture; it is simply that in terms of the particular asset of "reputation" they have a much better opportunity than any American composer—and have often been inflated far beyond their intrinsic value.

BAD: The effort to develop in his own way is met, for a composer, with constant frustration by the very demands of the situation. What appears to be an utter lack of responsibility toward the needs of its compositional faculty seems to be characteristic of most university music departments today. To make matters worse, departments are often willing to pay high prices for those who have profited by the culturally more responsible situations that exist outside the U.S. This is profoundly disturbing to all involved in it and should be to all American graduate students. For the latter cannot fail to realize that, if things keep up this way, they will be put out of jobs by young professionals trained elsewhere under more culturally responsible situations, when they graduate. We don't even approve of the results of our own education, so it seems (perhaps because education itself is not a commodity, only the act of educating). In fact in music one cannot help but feel that in composition, education is a training in obsolescence and is likely to be a hindrance in future teaching—for only thus can certain members of university faculties be explained today.

BAD: In 1969 (as not in 1959) the question of what can be useful to the next generation and how it can be presented has reached crisis proportions. If this continues to be the (what seems to me, healthy) situation of universities, teaching should be done by those who can constantly be concerned with the young and their attitudes, and not by composers who can only hope to interest the next generation by their honest work.

GOOD: In 1959 it used to be said that the university in America was the home of the arts—a place where they could be taught, studied, discussed, enjoyed, and developed outside of the mercantile pressures that link our society together. It is possible and much to be hoped that this continues and will continue to be true until the time when our society can find the kind of cultural consensus which will allow a large enough community of citizens to encourage musical composition outside of the university.

PAUL CRESTON

CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE

"The composer who wishes to teach must hav as graet a luv for teaching as for composing."

Unqualifyd or misqualifyd generalizations ar the graetest impediment to effectiv teaching and the most ineffectual method of lerning. To condemm or to laud in toto one composer's works, one style, one medium, one philosophy, or one period of history is to inculcate fallacious concepts. Applying that dictum to the subject under discussion, it would be wise to comment on the unqualifyd and misqualifyd statements that Stravinsky makes in his "Advice to Young Composers."

STATEMENT No. 1. "I would warn young composers . . . Americans especially, against university teaching." The question is not whether or not the "young" composer should teach in a university; it is whether or not the true composer who is equally competent as a teacher should be involvd. In less recent times the platitude offen reiterated was, "If one cannot do, one teaches." Altho it is partially true today in the teaching of theory and composition, a number of directors of music colleges hav realized that it seems obvious that a theorist should teach theory and a composer, composition. However, that generalization must be properly qualifyd: the true theorist who is a true teacher and the true composer who is a true teacher should teach his particular subject.

The consummat artist is not necessarily the competent teacher. For the creativ artist develops in a graeter degree thru the intuitiv process; the teacher develops thru the cognitiv-analytical process. The composer, therefor, would teach primarily by exampl, the teacher, by precept, and the composer-teacher, by both exampl and precept.

In music (as in life) we ar offen impelld to choose between two equally important principls, factors or objectivs. Which is mor important: quantity or quality, technique or interpretation, form or content, conception or craftsmanship, the means or the end? One need not and should not choose one as mor important than the other. The technique that does not serv interpretation or the interpretation that is not supported by technique is frustrating. Masterful craftsmanship devised for inane conceptions, and ingenious form that clothes futil content ar unjustifiabl. Technique and interpretation, craftsmanship and conception ar equally important.

To return to Stravinsky's misqualifyd generalization: it is the "immature"—not the "young" composer (since it is possibl that a "young" Mozart could be mature or an "old" composer, immature)—that should be warnd against teaching of any kind. For such a practice would fulfill no worthwhile artistic or didactic function; it would not contribute to the development of the composer or the student. Stravinsky's statement must be further qualifyd so that it would be: "I would warn [immature] composers [who ar incompetent teachers] against university [or even private] teaching."

STATEMENT No. 2. "The real composer thinks about his work the whole time." Obviously, Stravinsky means by "his work" the activity of composing. If the real composer thinks about composing continuously, when does he think of his physical self, his spiritual self, his philosophy of art and of life, enlarging his knolledge and understanding of the world, physical and mental relaxation, erning a livelihood, his family and frends, and just being a decent human being? Is he to be a disembodied spirit neither in or of this world? Is he never to recharge his intellectual battery by rest or other activities?

As an antidote to Stravinsky's statements I should like to submit my own Advice to Yung Composers, particularly in reference to teaching. The composer who wishes to teach composition must hav as graet a luv for teaching as for composing. He must not be satisfyd with just a smattering of knolledge of his subject; the sciolist attitude in teaching is tragically all too prevalent, especially in theory and composition. As a composer, he must develop his own philosophy and his own style of composition. As a teacher of composition, he must apprise the student of all the resorces and styles for the student to determin what best communicates his musical ideas.

INGOLF DAHL

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

"J'apprenais en montrant aux autres, et

j'ai fait quelques bons écoliers"

(Diderot: LE NEVEU DE RAMEAU).

Who among the contributors to this issue would not prefer to have been invited to compose a piece of music instead of composing paragraphs of words? Who would not prefer to have started his career as composer for ballet companies, as collaborator with poets and conductors, as commissionee of European radio networks and opera companies instead of teaching music theory, traditional counterpoint and perhaps, say, the techniques of total serialization? Stravinsky is right when he points to the problems of a milieu in which a composer's words are what he gets paid for, or invited to symposia, rather than his music. But economic facts are inescapable, and the Craft-Stravinsky quote, with its polemic overtones, is about equally far removed from the realities of a young American composer's circumstances as many of the young composers are themselves now removed from the realities of music making.

If the young composers' lives were spent entirely with the prime business of writing music there would be a much larger, richer supply of scores available for performances ("what performances?"), but even Stravinsky himself could have enriched our lives with many more compositions if partially economic facts had not made such demands on his time as a conductor and pianist. The successes of such programs as the one of the Ford Foundation-MENC-Contemporary Music Project, where young composers were paid to function, in every sense of the word, as professionals showed clearly that "happiness is to be loved for the music one writes on command." In the absence of such a direct relationship between the economics of the composer and his creativity the dangers of the academic environment are clearly apparent: The dangers of cloistered isolation; separation from music as activity; doctrinairism; abstract analysis—and eye-motivated note-spinning; underdevelopment or deterioration of the mind-ear balance; gradual removal from "reality" and growing unconcern with the performer, if not downright arrogance toward him; disdain for the listener; over-involvement in the minutiae of craft, in the dancing of one's own dance on the head of a pin. The eventual results in feelings of frustration, in the drying up of creative resources because of lack of contact are only too predictable.

Contact, however, is just what the American college music department can offer to the composer-teacher as well as to the composer-student, and it is here where the positive aspects of economic necessities should be seen. The college campus can indeed form the "right contrast for a composer's noncomposing time," but this has as yet been only partially realized. There are two types of contact which offer themselves to the composer (under this term henceforth both teacher and student are to be understood): the contact in a "horizontal" direction and the one in a "vertical" direction. The former refers to the large resources of the applied music studentry, performing faculty, humanities faculties and their libraries, the whole practical-intellectual beehive of activity and thought on a campus. The latter refers to the necessity for the composer to explore and master compositional techniques of historical periods of considerable variety.

The first type of contact provides not only essential points of reference to music as it is made, but also a laboratory, trying-out arena and ear-testing grounds. In this context the following parenthetical remarks may be pertinent: Being close to performers on a campus can help the young composer to become, quite simply, a more skilled professional. This would include the awareness, or perhaps reinstatement, of self-evident musical ethics, in which a composer's abilities of solfège are equal to his abilities of holding a pen ("Papier ist geduldig . . . "). The reasonableness, in other words, of the premise that it is both immoral and unprofessional for the composer to write down details of rhythm and pitch which he himself can neither produce (even by tapping a pencil, humming, whistling, foot stamping, etc.) nor hear correctly when produced by others. The availability of contact with performers on campus is here of inestimable value. More than that: In concert with the applied music faculty, performance organizations, and music students the function of the composer in the college can and should include the working toward the presence of the creative component in the musical experiences of the whole academic community, similar to the proper function of the playwright in the drama department, the painter in the art department, etc.

In another direction, the demands of the teaching of theory lead the composer to a study of compositional techniques of earlier periods. Who has demonstrated more gloriously than Stravinsky himself how fruitful such a "vertical" contact can be (down into the mineshafts of Renaissance and Baroque music, up into the turrets of the "new thing [that] makes the new generation new")? The enforcing of the study of traditional techniques is now perhaps considered as the "wrong contrast" to a composer's creative work. The discrepancy between the value of traditional skills of composition and what is now variously known as "relevancy," "avoidance of anachronisms," "aktueller Stand des Komponierens," etc. is in the foreground of the preoccupations and concerns of every theory-composition teacher. On this subject G. Ligeti presents pertinent thoughts in his discussion of his own composition classes in Three Aspects of New Music (Stockholm, 1968) and he suggests a zweigleisige Methode [i.e., two-track method.—Ed.] of teaching which many of us have carried out for some time. In spite of his repeated references to "out-datedness of techniques," "unusableness of skills," etc. he emphasizes the value of schooling in the solution of traditional problems and a refinement of a sense of values through traditional models. How can one praise enough the stimulation, the exhilaration of contact with historical problems and their solution by masters of past and present? Is not one of the rewards the awareness, caused by the demands of the teaching profession, of the presence and nature of artistic problems where no such awareness existed before? In Arnold Schönberg's words:

I think I resolved these problems, but this merit of mine will not mean very much to our present-day musicians because they do not know about them and if you tell them there are such, they do not care. But to me it means something.*

Stravinsky's harsh words can be most constructively interpreted if they are made to serve to remind the composer, inside or outside of the academic environment, that he is a musician first, a theorist, analyst, engineer, design instructor second. His function must always be to straddle the world of words (verbalization, diagramming, defining of techniques) and that of sounding notes (rolling up the sleeves and involving himself with the makers of music). With this attitude of "comprehensive musicianship," within the structure of the academic life, the benefits to the creative development of the composer can in the end almost equal the satisfactions of having his ballets produced by Russian choreographers.

*From a letter to Alfred Frankenstein (San Francisco Chronicle), March 18, 1939, referring to the problems he encountered in arranging Brahms' Piano Quartet, Op. 25 for orchestra; as quoted in Erwin Stein, Arnold Schoenberg Letters (London: Faber & Faber, 1964), p. 208.

CECIL EFFINGER

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO

"The university environment is not a way to failure either."

The most important point in the admonition is the first statement: "A composer is or isn't." A further point is then made that the young composer should be careful about how he spends his non-composing time, and that teaching theory might not be the best way. It seems most composers have to spend their non-composing time making a living, which is not the best way either, but you can't always have everything! Ideally, the composer would like to make his living composing and spend his non-composing time in ways of his choice which might replenish and enrich his life, and which might feed back to strengthen his creative efforts. However, the well-known economic, social, and artistic factors of supply and demand make this ideal a relatively rare possibility.

Obviously, then, the American university community does have a lot to offer: income, stimulating people both in music and in contrasting disciplines, free hours, frequently a near-professional musical environment and challenge, sharp audiences. Naturally this is tempting for any composer (would-be or otherwise, young or not). As for his academic involvement, this may range from a smattering-of-music course for freshmen in a finishing school to a graduate seminar in aesthetics. The composer who is aware of his own needs for balanced existence will usually decide about these things.

Nor is the tough professional field closed to the composer because he teaches. Any university recognizes such outside publication, performance, and commissioning of music from its faculty as an important part of the function of the composer and a credit to the university itself. Furthermore, in the 20th-Century American university set-up the composer is free to decide whether he will write for his colleagues, for students, for fully professional situations, for stipend, or not. I can think of many fine composers, from other countries and in other centuries who might have considered this a fine deal, and I doubt that their talents would have changed one bit, for better or worse, in such a marvelously free circumstance.

Which brings us back to what I feel is the more important point, the warning to the young composer to take into account the fact that he must effectively balance his practical life around that gift in his nature which makes him truly a composer, and that furthermore there is no easy way to do this, any more than there is an easy way to compose. The university environment with its many advantages in our time and place, is not to be reckoned as a door to success for the composer. To this, I would agree and add, it is not a way to failure either.

But it does seem in these days, even more than in 1959, that the young composer should be emphatically told, "A composer is or isn't." There is nothing that can help him if he isn't, nor stop him if he is.

ROSS LEE FINNEY

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

"The single most important factor in an artist's growth is what he learns from his peers."

Stravinsky's remarks contain a great deal of sage wisdom and should be read carefully by young composers who make their living by teaching. His meaning is clouded by the pejorative quality of one sentence and I find the following rearrangement clarifying:

The real composer thinks about his work the whole time; he is not always conscious of this but he is aware of it later, when he suddenly knows what he will do. I would warn young composers, (too,) Americans especially, against university teaching. The numerous young people on university faculties who write music and who fail to develop into composers cannot blame their university careers, of course, and there is no pattern for the real composer, anyway. The point is, however, that teaching is academic (Webster: "Literary . . . rather than technical or professional . . . Conforming to . . . rules . . . conventional . . . Theoretical and not expected to produce . . . a practical result"), which means that it may not be the right contrast for a composer's non-composing time. (However pleasant and profitable to teach counterpoint at a rich American Gymnasium like Smith or Vassar, I am not sure that is the right background for a composer.)

I regret that last sentence (an American "Gymnasium," by the way, is where you play basketball) since it seems to me impolite and a little silly to pick out two eastern women's colleges as representative of the American university. However, when one considers how ignorant many Americans are of the university pattern that developed as a part of our frontier experience, we should not let our reactions to this one remark get in the way of valuing the timely wisdom of Stravinsky's statement.

A young composer must not impair the continuity of his thought, and yet, composing does not take up the full time of an energetic individual, nor does it bring in an income on which one person can live, not to mention a family. That is the dilemma. As Stravinsky points out there is "no right pattern" for the composer and the university is not to blame, but it is indeed doubtful that the best "contrast" is to teach theory. To perform music, to conduct music, to teach instrumental performance as Bartók did, or to do some totally unrelated work like Ives: these ways of making a living can be less distracting. But to write criticism or hack music for TV is worse than teaching. The university has no corner on the academic mind. The European economic patterns of independent wealth, parasitic dependence on an upper class, or more recently, government organization into unions, does not seem to me a better solution for the composer than making a living through his skills, even if that means teaching the young. What is more, I am not sure that teaching is academic. Is education "Literary . . . rather than technical or professional . . . Conforming to . . . rules . . . conventional . . . Theoretical and not expected to produce . . . a practical result"? If so, it should be changed.

Certainly "a composer is or isn't" but so is a mathematician or physicist. The need is to make it possible for the young composer to work, to be heard and to become known. I have not been impressed by the opportunities open to young composers in Europe or within the concert establishment of this country. Our conservatories and universities are more progressive and always because of the willingness of an older composer on the staff to care, to go out of his way to help a younger person. A real talent will revolt against pedestrian teaching and that revolt may be the most valuable part of his growth. I have seen no convincing proof that a real composer becomes dull from studying or teaching counterpoint. If I were to choose the single most important factor in an artist's growth it would be what he learns from his peers. This opportunity varies, of course, from university to university, but considering the size of this country, the environment that the university furnishes for young people far from the "cultural centers" is a great democratic achievement.

But university environments do vary and most administrations impose teaching schedules on artists three times as heavy as they do on creative mathematicians. The administration justifies this inequity on the grounds that the artist has less bargaining power. If a composer's energies are deflected from his work by long hours of teaching, committee assignments and unproductive busyness and he reaches the point where he can no longer think "about his work the whole time," then he had better heed Stravinsky's advice and either fight the administrative power or do something else for a living.

CARLISLE FLOYD

THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY

"The greatest threat to the creative artist in a university lies in the academic milieu itself."

Having been on the faculty of a university school of music for some twenty years, I am in both agreement and disagreement with Stravinsky's point of view regarding composers in universities. What strikes me as one of the greatest hazards that confronts composers in universities is the danger of becoming doctrinaire, simply by virtue of teaching compositional principles and technics over and over again, and by the academic's tendency (and perhaps necessity) to "lock something in." I know composers whose point of view about composing, and whose own composing, has changed very little over a period of twenty-five years. It may well be that the same ossification would have occurred outside the university (and I frankly think that in most cases it would have), but, nevertheless, these composers were on the faculties of universities. On the other hand, it seems to me that teaching can be a great boon if a composer can remain flexible in his outlook: this is especially true nowadays when a teacher is bombarded by fresh and radically different ideas and approaches from students. The hazard in this, of course, is that one can become a victim of novelty and fashion and this can be as fatal as anything I know of.

Personally, I feel that the greatest threat to the creative artist in a university lies in the academic milieu itself, which fosters thought over feeling, cognition over instinct. There is a deadly temptation for the artist in this atmosphere to yearn for and to seek intellectual respectability on a par, say, with the natural and social scientists, and this can completely undermine his life as an artist. The academic mentality, as we see it in evidence on many campuses today, is, to my mind, at the opposite pole from the artist's impulse to self-expression. All these perils notwithstanding, I think the composer can still produce and grow within these institutions, provided, of course, that he has the kind of support and sanction I, myself, have enjoyed in my career as a composer-teacher.

ANDREW IMBRIE

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

"The composer's higher learning that only he can teach."

Stravinsky's denial of the composer's place in the university derives from a single assumption: that "teaching is academic," according to a dictionary definition of the term. If this statement were true, it would of course follow that composers should not teach.

But the statement is not true.

Let us begin by distinguishing between academic subjects and academic teachers.

Are harmony, counterpoint, composition academic subjects? Are they literary, non-technical, conventional, impractical? I think the answer is no. Perhaps harmony and counterpoint are conventional to the extent that rules are established and enforced. But surely this is done not for the sake of the rules, but to bring about a practical result. Rules define the simpler properties of the materials. First-hand knowledge of these materials comes from getting one's hands dirty with them. Stravinsky knows this, of course, and has repeatedly gone on record in support of the exact and fundamental musical disciplines.

There are some teachers, however, who teach these subjects as if they were academic. Perhaps they look on the study of counterpoint as a cataloguing and imitation of the stylistic traits of the Renaissance, composition as the study of "the musical forms." Perhaps they think of the rules as a list of observed statistical probabilities—or of a musical work as an example to illustrate a theory. Perhaps, indeed, they regard the study of music generally as a branch of the history of culture, and music itself as an object of contemplation rather than a field of action. Teachers of this sort are academic, sometimes in a bad sense, sometimes good. But there are few composers among them.

The university concerns itself with higher learning. Does the composer's need for practical training disqualify him from this concern, or does he perhaps have something to contribute to it?

We might compare the practical rules of music with those of chess. The latter are truly conventional because they are immutable. The rules of music keep changing, because they are based not on convention but on human sensibility. Certain convenient and successful procedures, which assure comprehensibility in a given type of context, become frozen into conventions for a while. But the same human sensibility which demanded comprehensibility soon demands change: so the conventions are at first disguised and finally overthrown. This process produces a new context, calling for new procedures to assure comprehensibility, which result in new conventions.

The cultural historian attempts to trace how this process may have operated in the past, but only the composer can himself participate in it. Only the composer can conceive of whatever elusive relations might exist between the historic process and the vividness of his own immediate musical awareness. If he chooses to teach, he has this precise advantage over his colleague: that his knowledge is first-hand. The historian, for his part, can claim greater objectivity.

The composer as teacher, however, must cultivate another kind of objectivity: that which allows him a glimpse into the student's world of feeling and experience. It is not enough for him to impart techniques—either his own or those of others; he must strike to understand the student's expressive needs. By the way, I see no difference between expressive needs and Stravinsky's "exact appetites." The teacher's job is to help the student to develop these and to gauge their "exact limits," so that they can become "indispensable human measurements."

In certain civilizations, notably the Oriental, the teacher-pupil relationship is almost sacred; this used to be true, to a lesser degree, in the West. The idea of the self-taught artist is relatively new. It seems to be bound up with a Romantic conception of the individual, which lends some credibility to the stance assumed by certain European composers (including Stravinsky), who claim to have learned little from their teachers and to have done it all on their own. From their testimony we are invited to conclude that anyone who acknowledges a debt to his teacher is weak.

It is true that in Europe the institutionalized teaching of composers, during the last century and continuing to the present, has reached a degree of academicism where the demands for conformity imperil the young composer's development. If he is talented, he is forced to rebel. It can be argued that this is the best thing for him: only in rebellion can he find himself. By coddling him we are making him unfit to survive.

But when rebellion becomes a prerequisite for acceptance into society, it rapidly generates its own brand of conformity, its own establishment. Thence follow inevitable new rebellions in an ever-increasing accelerando—to the point where music itself finally becomes the polemical football in a competitive personality game.

A mature composer can sometimes help a young one to avoid this trap, and to concentrate on the development of his real powers. He can remind him of the properties of his chosen materials as they are perceived in context, and of their possible structural capabilities in that context. He may even suggest alternative contexts, in order to stretch his pupil's imagination. What must begin as a technical exercise must end in liberation.

We may, as some believe, be reaching a point where our conception of the historical process itself needs re-evaluation. Our excessive style-consciousness has led us to a paralysis of self-consciousness—so much so that a tolerant eclecticism is now being thrust upon us as the only realistic attitude to adopt. Only a real composer knows what it means to have something to say, and what it takes to evolve the exact way to say it. It is this higher learning that only he can teach. He cannot impart the gift, but he can help provide the means and set the example.

In these brief observations I have said nothing about what the university can do for the composer, such as providing him with intelligent students, leaving him free to teach as he thinks fit, or allowing him to eat. My main argument for the composer's role as teacher is the possible satisfaction he may receive from doing something for somebody else.

ELLIS B. KOHS

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

"The imaginative and creative artist is probably also an imaginative and creative teacher."

A recent study of the economic situation of the writer, composer, painter, and sculptor in America today (Saturday Review, February 28, 1970) indicated that the vast majority of creative artists cannot support themselves by earnings from their art. Of these classifications composers appeared to fare the worst, 92% declaring they needed supplementary income.

There is no question about the composer's economic plight. If he has turned to college and university campuses, there are probably good reasons for that. Here he has some security, the stability that tenure can provide, an atmosphere conducive to reflection, and intellectual stimulation. Not all colleges may provide an ideal ambiance, and it is probably futile, therefore, to make broad generalizations about the merits or the disadvantages of college teaching for the composer. One cannot lump together, for such purposes, a small college with a handful of students, none of whom are music majors, with a large conservatory-type structure where large numbers of people are preparing themselves for a professional career.

Stravinsky, in his "Advice to Young Composers," warns against the teaching of counterpoint at a wealthy college. I am sure that he assumes that students at such a school would be dilettantes and have no genuine interest in developing professional skills, and one must admit that this condition might have a stultifying effect on a young composer. On this same page, however, Stravinsky points out that young composers who fail to develop cannot blame their university careers. I agree with this, and would add that the imaginative and creative artist, whatever his field, is probably also an imaginative and creative teacher. The person who falls into easy patterns, who is a willing victim of academic routine, would probably turn out to be as dreary in the concert hall as in the classroom.

All university and college faculty composers would like to be freed from committee responsibilities and have a smaller teaching load in order to have more time to compose. Perhaps the question is not whether or not to teach, but whether or not administrators can assist composers so they may have more time to compose, while still maintaining the fruitful connection with young people.

LEO KRAFT

QUEENS COLLEGE (CUNY)

"The university is the seedbed of ideas in the arts."

What does a composer need in order to function at his best? Most of us would like a live musical situation, opportunity to have our works performed well, an audience that will give new music a fair hearing, the stimulus of working with other musicians, and contact with new ideas in the art. In the U.S.A. today, where is there a better opportunity for a composer to find these conditions than on the university campus?

For whatever reasons, the world of the public concert is not a congenial environment for new music. To cite just one example, the later works of a certain Stravinsky, say, those written since 1913, are hardly ever to be heard in our concert halls. We rejoice in the fact that the master has lived a long and productive life, but as far as the commercial concert world is concerned, he might just as soon have died after writing Le Sacre du printemps.

Not so in the world of college music, where the moderns are alive, if not exceedingly well. A new and decisive development has brought the center of musical activity to the campus, and that within the last decade. I refer to the rapid growth of university-based performing groups. These have provided fine performances for a vast amount of new music, have trained young performers in the techniques of recent music, and have at least made a start at developing an audience for contemporary works.

Why young composers (why especially Americans?) should be warned against working in the very milieu that offers them the best possibility to practice their craft is an intriguing question. Isn't Stravinsky applying the criteria of his own formative years to an entirely different situation? He, of course, came to maturity at a time when artistic life centered around public performance, generously supported by private benefaction. The university must have seemed very remote from the scene of the action. But today, in our country, the university is the seedbed of ideas in the arts, as well as in the sciences and in politics too. Stravinsky's warning, with all the respect due to a very great artist, simply does not apply.

There is another important aspect to being a composer-teacher which I would like to emphasize. I mean the undeniable mental stimulus of teaching itself. By teaching counterpoint at Smith or Vassar or Queens, one is forced to examine the very basis of how music is made, how sounds combine with one another, what makes some pieces work better than others. And I am sure that this is the right background for many composers. Our use of words has confused the issue. We call our course "theory" when, in fact, it is a very practical course in how notes go. To quote the dictionary definition of "academic" is quite beside the point, since that definition serves to guide nobody in his teaching or composing. In the classroom, the teacher as craftsman has to know the answers to the basic problems of music and how it is made. Becoming a good teacher can only help a person to become a better composer.

These days we are working to bring into the classroom the freedom of the artist's atelier, the liveliness of the composer's studio. I think we are making progress. In a society increasingly hypnotized by the mass-produced product, whether it is something to eat, to wear, to listen to, or to vote into office, the university is the great stronghold of individualism (well, some universities are). A great university, indeed, will seek out not only individualism but even eccentricity. Anyone who has the audacity to write music in these times is indeed eccentric, and if he can function in any way as a useful member of a faculty his place is on the campus, in touch with his colleagues, with young men and women, with ideas and with new music.

LAWRENCE K. MOSS

UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, COLLEGE PARK

"Our universities are the American version of the traditional European patronage of the arts."

At this point (May 8, one day before the Peace March in Washington), there may seem to be other dangers for the composer in the university than those envisioned by Stravinsky. As I take it, Stravinsky's objection to university teaching is that it is too "academic," that is, "conforming to rules," and that this is not a proper contrast for a composer's time spent away from composing.

Now, the actual teaching may or may not be "academic" according to the composer's talents as a teacher, but the university scene at this moment is anything but "academic," if by that is meant the cloistered life, the peaceful groves of academe. On the contrary, we seem to be in the birth throes of what may be the first general strike in this country's history, and it is being led by the universities, and of course, more particularly, by their students. Whether we agree with them or not (and I, for one, do), they have torn down the barrier that traditionally separated the American university from the "real world." And no matter how all this ends, I suspect that barrier will never go up again as it was. Stravinsky's quotes from Webster's definition of academic will never apply with their old force, if indeed they ever did. We will have learned from our students. Maybe we should thank them as Schoenberg did in the preface to his Harmonielehre. One learns both in and out of the classroom.

It has been pointed out that our universities are the American version of the traditional aristocratic European patronage of the arts. As such they bring together performing ensembles, sponsor concerts, and subsidize (part-time!) composers. Of course this takes money—massive amounts of it—as it always has. But perhaps today it takes even more, since one of the "instruments" needed in today's musical workshop is beyond the reach of any but the institutional sponsor. A good, professional electronic studio—one that can whet a composer's appetite with the variety and quality of the sounds it is capable of producing—seems to cost in the neighborhood of $20,000. Some money can be sliced off by economies in the tone-generating equipment, but the major part of the expense—good, studio-model tape machines—will always be beyond the resources of the single composer. In Europe he might turn to the radio stations; here he will inevitably turn to the universities.

There is an added bonus in the universities being the sponsors of the electronic studio, because we can see that, potentially at least, they are in a unique position to further new developments in the theatre, among them a new collaboration among the arts which will assuredly include electronic music. I can envision a successor to opera in which electronic music supplants both orchestra and singers, just as slide and movie projections supplant sets and costumes. All this will take place in a new kind of non-operatic space, one not conditioned by the proscenium arch of opera and concert stages. Of course this development calls for a close collaboration between our music, art, and architecture departments, and perhaps it is visionary to think that their traditional rivalries and bickerings can be put aside in a higher cause. But Wagner's Gesamtkunst must have seemed a good deal daffier until good, mad King Ludwig came along. Now all we have to do is find him (King Ludwig, that is) among our college presidents. Perhaps after the events of May it will be possible.

There are of course many other benefits more traditionally associated with teaching music in the university—the stimulation of students (who seem in my fairly brief academic career to be growing brighter), large amounts of "free" time, possibilities of interesting, non-commercial concerts, etc. But there are dangers, too, and not just those that Stravinsky mentions. Perhaps the foremost is that of being isolated from a larger, non-university audience. Not necessarily the one that likes Lawrence Welk, but the one that enthusiastically follows avant-garde art and theatre. This audience is more conspicuous by its absence than its presence at our university concerts. Is this because we "academic" composers have grown used to composing for one another? Are there certain "in" styles, academic or otherwise, which the university's isolation tends to foster? Finally, do our schools not inevitably become "schools," clusters of students around the Great Man, where individuality and poetry are less prized than adherence to a locally established common practice?

There is an undeniable greyness about the average concert of contemporary music, whether on the campus or off. I'm sure that most of this is due to the unprecedentedly large number of composers writing today, with its inevitable dilution of intensity and originality. However, speaking of the truly worthwhile among these works, I think we can ask ourselves whether their creators have not demanded less of themselves than they should, content to please their colleagues rather than that much more elusive, threatening audience, the cultivated general public. I know from my own experience how much easier it is to strive for local acceptance rather than a problematical, possibly "unsuccessful" (because locally unfashionable) original vision. But unless we strive for this vision, against the grain of the university, so-to-speak, we will surrender experimentation, new ideas of form and substance, to those for whom music and art in general are at best social commentary, part of life's process, and in any event not to be taken "seriously."

I am thinking of the dadaists, the followers of pure chance, those who in advance disclaim any responsibility for their work. Their ideas are often provocative, but just as provocative is their ignorance of the tradition, and the ways and means it offers to further such ideas—in a word, craft. And we, who must deal with the tradition in our work as university composers, are the keepers and disseminators of this craft. If we use it only in the service of our immediate "school," in short if we become "academic," then we surrender the growing edge of music to those for whom music is a game, and no more. And that, in the deepest sense of the word, would be a shame.

JOHN POZDRO

UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS, LAWRENCE

"One is constantly and deeply immersed in the business of what music is all about."

No one can deny that the best possible situation a composer can find himself in is one where he has unlimited, unrestricted time for his work, a case of having at his disposal however much time he needs, whenever he needs it. For it is only with great quantities of this precious commodity that he can develop as a creative artist to the fullest extent. Unfortunately, few composers can aspire to this happy state of unlimited time. Even "full-time" composers often become bogged down with personal obligations or peripheral commitments that take valuable time and energy from preferred compositional activity.

The composer who must indeed earn a livelihood, and who wants to continue writing under the most suitable conditions, may well look to teaching as a career. Now I do not offer this solution as a crass decision to be made with teaching coming out second best in the scheme of things. This need not be the case, and if it were, the solution would lack integrity. On the contrary, I believe that education benefits from the contributions of people who are deeply engrossed in their art—they bring a needed drive and lifeblood into the teaching program. True, the teacher-composer soon discovers that teaching is an art in itself, with responsibilities of the highest sort, and that it makes heavy demands on his energy and time. Still, I do not know of any other profession which offers a more likely environment; and is there any which will provide as much time as the composer needs and wants? In teaching we have the seasonal breaks, and time off between terms. In the beginning, at least, the instructor finds fairly large segments of time in the daily schedule for his own work. Not least of all, there are leaves, sabbaticals, and research grants in every growing numbers.

I suggest teaching as a career, contrary to the view taken by Stravinsky, in which he warns young composers against university teaching because teaching is "academic." It may be Stravinsky's lack of university teaching experience that leads him to the conclusion that since the dictionary provides a particular definition of the word "academic," then that defined situation is what we can expect to find on the campus! I submit that educational programs are not to be judged by, nor are they evolved from definitions or clichés. Moreover, the thrust of modern teaching has been to relate as much as possible the student's training to the conditions he will face as a professional. This is what makes teaching exciting, for it is in this struggle to relate that one is constantly and deeply immersed in the business of what music is all about. And it is this aspect of teaching that gives the teacher-composer an environment of significant, potential value to his development as a creative person!

I need hardly add that in teaching, one is surrounded by highly capable, if not professional colleagues; also, there is a ready market for the performance of his music. The instructor has access to library resources he could never hope to own, and there are the keen, young minds of the students whose questions and reactions have the wonderfully disarming manner of keeping the teacher in constant muse about his own ideas.

Of course, I am describing a compromise situation for the hard-core composer. But I stand at the place, now, where I firmly believe in the career of the teacher-composer and his role in the university. Thank Heaven for a giant like Stravinsky; music would not be the same without him. Would the future of music be the same, however, if there were no professionals to come into the ranks of teaching to share their skills and experience with the young who need and want it?

It is a privilege to teach, and it is of some small comfort to think that in addition to the personal gratification one may receive as a composer, he may now and then help some young, talented person to find his star a little sooner.

GARDNER READ

BOSTON UNIVERSITY

"A mature and wise composer can manage his dual life in the university without compromise in either area of his activity."

The groves of Academe, according to the immediate viewpoint of the composer residing therein, are either a secure and pleasant retreat, benevolently watched over by a tolerant and unobtrusive administration—or, they are a jungle infested by obtuse deans, waspish chairmen, and cretinous students, all of whom daily conspire to deny the teacher-composer the time, energy and will to create. No doubt the real truth lies somewhere between these polarized (and romanticized) viewpoints. One can endure an unsympathetic administration and enjoy stimulating students at one and the same time, and one can just as surely bask in the respect and genuine understanding of one's dean, chairman, and colleagues while despairing of untalented, ill-prepared and apathetic students which are his lot.

Utopia, I suppose, would end up by boring the creative artist into a state of complete inaction, while Hell would quickly drive him to seek greener pastures—though the verdant aspect of those more distant areas might well prove illusive. And whereas one composer might endure academic Hell for the good of his artistic soul, another might prefer the debilitating blandishments of Utopia as the lesser of two evils. Chacun à son goût, they say . . . .

All of which leads us to a consideration of Igor Stravinsky's own acerbic viewpoint on the perils of teaching and its probable mortal effect on the composer's development. That Stravinsky cannot be faulted on many of his statements in Conversations ("there is no pattern for the real composer . . ." or, "the real composer thinks about his work the whole time . . .") does not automatically lead to certification of his opinion that academic teaching can only result in conventional and academic music being written by the composer-teacher. That it has done just that in certain instances does not mean all university composers have become reactionary because of exposure to academia. Is Milton Babbitt a "conventional" composer?—or Roger Sessions?—or Leon Kirchner? Without naming names, some of our most traditionally oriented composers have never experienced prolonged associations with institutions of what we are pleased to call "higher learning." Instead, they have enjoyed a relatively unfettered existence during which a succession of grants, commissions, and prizes have nourished and sustained their physical and creative powers. On the other hand, not a few of our boldest and most progressive writers have spent almost their entire creative careers within the sheltered walls of the university, college, or conservatory. That their special, and to some, restricted environment did not thereby produce a dreary flow of "correct" but unoriginal musical expressions is surely a testament to the inherent ruggedness and independence of the creative spirit.

So what does this all prove? Only, I think, that the individual creative person determines for himself the path he will take, whatever the environment in which he works. He can succumb to academic demands and pressures, or he can rise above them; he can allow himself to be overwhelmed by trivia, or he can hold steadfastly to priorities of time and energy; he can waste himself in unimportant, extra-curricular activities, or he can reserve his powers for what is of primary meaning to his whole being—his creative work. A mature and wise composer can manage his dual life in the university without compromise in either area of his activity; a split personality need not always lead to creative schizophrenia, nor a double career always result in a common mediocrity.

In an earlier article* I stressed the fact that the resident artist, whether composer, painter, poet, or writer, contributes to and receives from the college or university in almost equal measure. If he lives, as he must today, in a society that does not support him through his creative work alone, he still must find the financial security and the encouragement to produce somewhere. Better, one believes, in the groves of Academe than in the wasteland of Hollywood or the marketplace of Madison Avenue.

*Gardner Read, "The Artist-in-Residence: Fact or Fancy?," Arts in Society, III, No. 4 (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1966).

GEORGE ROCHBERG

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

"The single decent option left the American composer is the academic life."