Since the mission of The College Music Society is to act as a forum for the exchange of ideas in the profession, it is quite natural that the pages of Symposium should continue to be open to discussion of the Contemporary Music Project, the philosophy of music education and the approach which is in the forefront of the effort to bring our actions into some kind of balance with our ideals. The present article offers a series of comments on CMP 6,1 a recently published booklet written by David Willoughby, which gives the clearest idea yet of what the Project stands for. No attempt is made here to touch on every aspect of the program. Rather, the article concentrates on a number of aspects which, in my judgment, are the most significant. I make no claim to utter objectivity; my point of view is that of a friendly but independent critic.

CMP 6 contains three large sections. The first puts the concept of comprehensive musicianship into the context of contemporary educational thought. The second draws some conclusion from the Project's various experiences to date, while the third consists of a summary and ideas for future activities.

The Contemporary Music Project is often subject to a certain amount of misconception simply because of its name. At an early stage, the Project was indeed concerned primarily with contemporary music and with the appalling inability of many school teachers to deal with the music of our time in a way that made sense to their charges. But it did not take long to discover that many teachers could use help in dealing with any kind of music. From that point the emphasis shifted to developing better (defined as more comprehensive) musicianship. Today, those working on the Project refer to CM, meaning Comprehensive Musicianship. A healthy bias in favor of contemporary music of all kinds may fairly be attributed to the Project as it now exists, but its scope is universal.

CMP philosophy is built on a body of basic learning concepts, stemming from a concern for "humaneness in teaching." The intent is not to impose a well-organized body of knowledge upon a passive young recipient, but rather to stimulate discovery of music, one of life's most joyous activities. Evidence from Whitehead, Dewey, Mursell, Bruner, and from the Tanglewood Symposium2 and the Yale Seminar3 is adduced to make the case for steady growth on a conceptual basis, using the "spiral of learning" approach. This means that basic ideas are introduced at the earliest possible moment in the child's development, then restudied in increasing depth in successive stages of the educational process.

In the course of the discussion, a dichotomy is set up between Gestalt psychology and behaviorism, with the evidence stacked in favor of the former. The very brevity of the presentation is enough to make the either-or choice a rather dubious one. To some extent every teacher wants his students to see his subject whole, and yet all human behavior involves an interplay of stimulus, response and reinforcement. It is not only the Gestaltists who see the learning process as a "field," by any means, nor do Gestalt-oriented teachers have the monopoly on "thought and conceptionalization" that seems to be implied on page 8. Perhaps the message of the first section CMP 6 is that those of us who teach on the college level would do well to go back to some of the classics in educational psychology and take the opportunity to review our basic philosophies of teaching.

Without attempting to define precisely how significant the philosophical and psychological background of CMP actually is, one may still readily identify the point of view being espoused. "Learning as an outgrowth of personal discovery is integral to the theory of comprehensive musicianship."4 It is difficult to disagree with such a statement. What it can lead to is another matter. The goal is to develop a person who can perform the three musicianly functions: to be musically literate (compose), to understand and articulate what he understands (analyze), and to perform (intelligently). None of these goals is new. What is new is the notion that every student should be competent in all three in an integrated way. Which means, once for all, the abolition of the compartmentalized curriculum that breaks music into small fragments and leaves the hapless undergraduate with the task of putting the pieces together. CMP says that it is the faculty's responsibility to present the student with the whole thing.

That such a radical approach—I call it radical because it gets to the root of at least some of our problems—will encounter strong opposition goes without saying. Such opposition will not necessarily come from those who are devoted to the furtherance of traditional ideas, for CMP certainly offers a constructive way to adapt tradition to the world of today. I should think it more likely that opposition would come from those who associate the conventional compartmentalization of courses with a disciplined way of teaching and equate CMP with lack of intellectual rigor and with "doing your own thing" in the most superficial sense. Indeed, there has been so much discussion about giving students what they want that one is entitled to ask where CMP stands in this regard. The answer is that CMP offers as good an opportunity for structured study as any other point of view, provided that the faculty is able to widen its own horizons and work out not merely separate curricula for various courses but a curriculum for all courses. The controlling factor has to be nothing less than the discipline of the material itself.

The implication that all three areas of skill are to be taught in each course pervades CMP 6 and virtually all statements emanating from the Project. Our college courses, however, are conceived more narrowly. What are the implications of this particular point of view? A counterpoint class is not usually considered to be the place in which to work for the improvement of performance, yet I cannot be the only teacher to have discovered that an insistence on better performance of counterpoint exercises leads to better counterpoint exercises; so does the use of those exercises as ear-training drills. If we talk about the history of a piece without also talking about just how the piece works, we are teaching our students that historians may be ignorant of analysis; if we study a piece in depth without also placing it in a historical context, we are teaching our young theorists that they may be ignorant of their own past; if we train young performers without also conveying the historical and formal aspects of the music they are practicing, we are forming mindless robots.

An important argument for including the widest possible range of musics in our courses is concerned with value judgments. Whether we realize it or not, we are teaching that the music studied in class is worthy of our best attention, and that which is not studied is not worthy of such attention. As a case in point, if the music of black Americans is never mentioned in our history and theory courses, that music is relegated to second-class citizenship. The plea that materials are hard to come by can no longer be taken seriously, and CMP has made a notable contribution with the publication of CMP 7.5 There is no excuse for music educators on all levels not to do their part in fostering understanding and mutual respect among the many ethnic and religious groups that comprise the American people.

At the same time, the inclusion of a wide range of musical cultures can easily lead the student to believe that all are of equal value. As the pendulum swings from the exclusive study of the common practice period to the acceptance of world music, the impressionable youngster may conclude that the latest rock hit, the mating call of the wild Eskimo, and the Ninth Symphony have the same artistic merit. Now, I think it unlikely that anyone can be completely objective, and I'm not at all sure that we should try; certainly the enthusiasm of the teacher for a piece should be made plain to the student. But we should realize that we are expressing value judgments as we teach, and we must give serious thought to the implications of our choices and of our expressed preferences.

When possible shortcomings in our choices become apparent, we sometimes comfort ourselves with the thought that students will make up in one class what they miss in another. There are two things wrong with such an assumption. First of all, how many curricula are so meticulously designed as to insure that all aspects of music are indeed studied in four years? Second, even with an ideal curriculum, the student is left to integrate what he has learned under different headings at different times. Do we seriously think that one semester of conducting will make much of an impression on a senior who has not been actively engaged in conducting in any of his other courses? Wouldn't the orchestration class mean much more to the young person who had written his exercises for instruments and voices and heard them played and sung for three years? How long will the majestic sweep of the history of music be relegated to a one-year course and never be studied in other courses, where it would create a rich context for detailed analytic study?

One of the questions raised in CMP 6 concerns qualifications for teaching music in a comprehensive way, for a crucial factor in effectuating any new plan is personnel—a syllabus on paper means little in itself. CMP candidly states that its success varies dramatically with the caliber and dedication of the faculty member concerned. Apparently their experience has not been very different of that of the Juilliard School and its well-known course in the Literature and Materials of music. In those cases where the teacher was master of both L and M, the course worked famously. But the number of highly gifted teachers is never very large, and it may indeed take a somewhat more gifted teacher to manage a comprehensive course than a narrower one. Perhaps the main thrust of the next few years should be to attract more of the best young minds in America into the field of education in general and music education in particular.

While few would deny that a musician should be what William Schuman called a "virtuoso listener," the notion that music teachers need any specific training in listening skills and aural analysis is not generally accepted, to judge from college curricula. Is it safe to assume that the skills acquired in various and sundry courses will automatically be transferred to the listening experience? Hardly. But, before we rush on to design another course (the standard academic approach to all problems), why can't concepts and techniques be discovered progressively through listening to appropriate works, both in class and out? All music courses can make good use of listening and can serve to improve auditory skills if listening is built into the structure of the course in a systematic way.

CMP 6 tells us that one attempt at using counterpoint in the integrated program was less than successful, but with this mysterious statement the subject is dropped. Later comments in this article will deal with possibilities which emerge when counterpoint is integrated with harmony, but it would be interesting to know exactly what happened in the case alluded to on page 67.

CMP did not create the situation we find ourselves in, with too much to do and too little time to do it, but it has called attention to the fact that two years in which to learn "theory" is just not enough. Considering what we all know to be true—but what many administrators fail to recognize—that we are responsible for teaching information, skills, and the constance interaction of both, the third year becomes an absolute necessity. Although CMP 6 does not specifically state this, I take the position that any student whose theory training comes to a halt after only two years is getting short shrift indeed.

One of the headings in the booklet is "Integration and Synthesis." What is being integrated and how are the elements being synthesized? Specific examples are shown in a lesson based on a movement of a Mozart Piano Sonata, and the reader is referred to page 42 for an illustration of how the study of one composition may serve many purposes. My only reservations concerning this discussion and CMP's ideas on music theory center on the question of tonal structure as an underlying common element of music. This will be referred to at a later point in the present article.

On what levels is the CMP approach most effective? Its proponents argue that for the "spiral of learning" concept to make its effect, the approach should be applied from kindergarten through graduate school. Having seen what happened when a comprehensive approach is used with college freshmen whose previous musical experiences have been extremely narrow, I am inclined to say that college is too late to start such an approach. Of course it isn't, and better late than never. But, if music is part of general education, then our youngsters had better learn the universality of music while they are learning about the world in which they live.

As music teachers throughout the country are learning to their dismay, it is increasingly difficult to justify music's place in the elementary and high school curriculum. And if by teaching music on those levels we mean imposing a few Anglo-American folk songs on an unwilling class and drilling the band all year to play six pieces for the Big Concert, can we as parents deny that music is a frill subject? Only if music is woven into the fabric of elementary and secondary school education from the very beginning, related to other subjects and used to develop the capabilities of the young person in listening, writing, and performing, will we be able to maintain and even enlarge the place of music in education.

Such an approach will inevitably bring about a conflict with the most conspicuous aspect of music in many of our schools today, namely, the performance activity. It is painfully clear that in many schools the enemy of music is the musician who conducts the band, orchestra or chorus. By concentrating the efforts of his young charges on the preparation of a few show pieces (why is "educational music" so uninstructive?), he shows the students what music is in this country—namely, a commodity to be exploited, and by means of which the students themselves are exploited for the greater glory of the conductor and/or the school administration. What do students learn about music in a performance activity? Recently the suggestion was advanced that a student who had participated in high school performance activities for a number of years should be qualified to take the Advance Placement test in music successfully. How many high school music teachers would even consider taking that idea seriously? Of course, conductors explain that they can't turn their rehearsals into classrooms, and that unless the group performs successfully it will lose its raison d'être. No one can deny that a performance group has to perform, and as well as possible, but why can't the student learn a great deal about music at the same time? CMP argues that the role of the school performance activity is to teach—it is not alone in this, of course—and the Project has provided demonstrations of how this can be done. Thus, it has suggested alternatives to the rote-like preparation for performance that characterizes so much musical activity in our schools today.

The report on the 1969 CMP workshop6 held at the Eastman School of Music remarks that there is "no totally embracing theory of music." There certainly is not, and most of what we musicians call theory is, in fact, a compendium of practices—how sounds have behaved in certain contexts. But the above statement, the reference to Hindemith's "field theory," and indeed the entire publication, points to the neglect of the ideas of Heinrich Schenker, and this absence can only be considered a major omission. For lack of the countless insights revealed in Schenker's article and books, in Salzer's Structural Hearing, and in Salzer and Schachter's Counterpoint in Composition, the attempt at integration of the elements of music theory falls short of its goals.

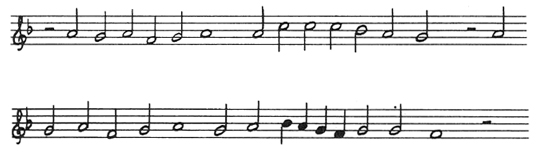

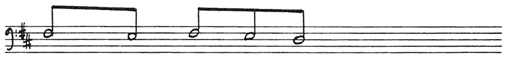

Pursuing the questions of integration, which is discussed in the booklet at some length, CMP's idea is that there are common elements in all musics, and that the study of music should unfold from an approach that sees all manifestations of music in terms of those elements which are in common. On the face of it, it is obvious that all music has pitch, rhythm, tone color, texture, interrelating and creating formal organization of some sort. But, to take melody as an example, what do tonal melodies have in common aside from their surface characteristics? Are there any kinds of principles to govern their rise and fall? Let us compare two melodies, quite different stylistically and see what they have in common.

Ex. 1.

| Jacques Arcadelt | Chanson | 1554 |

Ex. 2.

| Beethoven | Ninth Symphony, IV | 1823 |

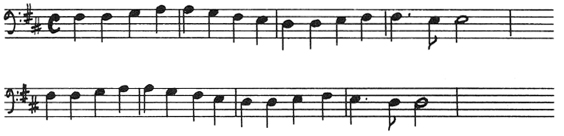

Ex. 3.

Ex. 4.

Ex. 5.

Ex. 6.

A first inspection shows that both melodies are in quadruple meter, in the major mode, and use a limited range. What else can be said about the pitch relationships? In order to find what it is that binds the notes together in an integral whole we may try in some way to summarize each melody. A list of the pitches in the Arcadelt excerpt is shown in Ex. 3. Can these be grouped into smaller units? The first three notes consist of a tone, its neighbor, and the return to the first tone. The G is dependent on the A for its meaning, and the A may be defined as the more important structurally. There follows one of the most frequently encountered elaborative groups in tonal music, a skip in one direction and a return to the original note by way of a passing tone. Again, A is the controlling note, after which the same four-note group is heard in inversion. The three short units have all been built around A, which they elaborate or prolong. The G which follows is not elaborated and is not an elaboration; it is the second independent note. The tonal structure of the phrase involves a prolongation of A and a move to G, from scale degrees 3 to 2. The gesture ends with a feeling akin to that of a semicolon, and is answered by another gesture, 3 - 2 - 1, that has more sense of closure.

The same reductive operations applied to the Beethoven melody, Ex. 5 and Ex. 6, reveal that not only are the same kinds of elaborative techniques used, including inversion (the skip is filled in both times) but also that the melodic structure is identical with that of the Arcadelt, namely, scale degrees 3 - 2; 3 - 2 - 1. If these were the only two melodies to have such similarities, the matter would be a minor curiosity. But as anyone can verify for himself, tonal melodies are all built up out of the same types of elaborative processes, and melodic structure either involves a thrust up from tonic to dominant and a descent to the tonic or, as in these examples, a descent. The tonal structure that is revealed by the reductive process has a status which may be described as that of an archetype. With a handful of basic structures to work with, the possibilities of melodic unfolding are seemingly infinite.

It follows that for the integration of music theory to be complete it would have to go beyond such common surface characteristics as melody, timbre, and texture to questions of tonal structure, and indeed the whole concept of structure and prolongation, implying that there are different structural levels in tonal music. Using such a conceptual approach the class could move from musical works (analysis) on to writing exercises and pieces (composition) and back again, showing the same principles at work in both analysis and synthesis. If anything resembling a "unified field theory" of tonal music has been invented so far, this is it.

As an example of just how much can be learned about a piece of tonal music by the application of the point of view I am proposing, the reader may refer to CMP 4.7 In the foreword, William Mitchell analyzes the opening of the sixth fugue from Hindemith's Ludus Tonalis. I seriously doubt that anything in the conventional theory course would adequately prepare a student to deal with this music. But by drawing on the concept of tonal structure—hence, structural levels—Mitchell shows the network of relationships that link the notes with each other in a clear and convincing manner. I suggest that application of this approach to any phase of tonal music would show the commonality between tonal composers of all periods. Not at all incidentally, the entire foreword is well worth reading for Mitchell's incisive comments on theory study, as much to the point today as when they were written in 1967.8

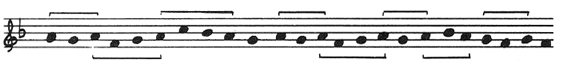

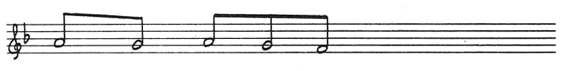

I emphasize the thought that the way to get to the heart of the matter is to think through the integration of what has been customarily taught in the courses called Harmony and Counterpoint. My own earlier ideas on the subject may be found in a previous article.9 The most powerful single pedagogical tool, in my judgment, is the body of procedures that goes under the heading of species counterpoint, not necessarily in the formulation given by Fux. The value of that discipline, of course, is not limited to music of the 16th century, and courses in "16th century counterpoint" waste a good deal of time for lack of relatedness to music of other periods. But, as Counterpoint in Composition by Salzer and Schachter has shown us in detail, the species principle unlocks the secrets of tonal structure no matter what the style characteristics. An approach to theory based on the linear view makes possible an understanding of a whole range of musical relationships, but it is also a specific way of developing fluency in writing skills.

Another aspect of integration which has received but little attention concerns the relation between history and theory. From what the undergraduate—the future teacher of our children—learns, the two are separate areas of study, with little connection between them. Few historians have shown any interest in the ideas of CMP, and while CMP 6 mentions the historical context of music as being important, implementation has been scant. Interestingly enough, our graduate students, certainly those at CUNY, have become impatient at the time-honored division between musicology and theory, and have shown keen interest in work that combines aspects of both. Whether we move towards a single class in all music subjects, or whether we work towards infiltrating important aspects of each into the other, some kind of synthesis seems highly desirable. A constructive step in that direction is proposed in a recent article in Symposium,10 which thoughtfully considers just what the synthesis of theory and history might mean and how it might be brought about. More is sure to follow.

| * | * | * |

It is too soon to summarize the effect of CMP thought upon contemporary music education. But in the relatively few years of its existence, the Project has had a considerable impact upon the ideas and philosophies of many in the profession. Perhaps a clue to the rising status of the Project is the fact that prospective employers are beginning to list CMP experience as a desirable attribute in job descriptions for theory teachers. Apparently instructors in other branches of music are not expected to be as comprehensive in their musicianship, at least so far. But it seems to me unlikely that our music schools can continue much longer to train thousands of young people in professional areas which, as such, become increasingly obsolete year by year, and train them so narrowly that they are not qualified to deal with anything else. A regard for our responsibility to our students, based on practical considerations and on our dedication to music itself, would indicate that every youngster should be trained as broadly as possible, with due regard for needed specialization, in order that he may survive in a world where change is the order of the day.

1David Willoughby, Comprehensive Musicianship and Undergraduate Music Curricula (CMP 6), Contemporary Music Project (Washington, D.C., 1971).

2''Tanglewood Symposium—Music in American Society," Music Educators Journal, LIV (November, 1967), No. 2 of the Tanglewood insert.

3Claude V. Palisca, Music in Our Schools (Washington, D.C., Office of Education Bulletin No. 28, 1964).

4CMP 6, p. 15.

5James Standifer and Barbara Reeder, Source Book of African and Afro-American Materials for Music Educators (CMP 7) (Washington, D.C., M.E.N.C., 1971).

6CMP 6, p. 111.

7Warren Benson, Creative Projects in Musicianship (CMP 4), Contemporary Music Project (Washington, D.C., 1967).

8To quote just a few lines, Mitchell says ". . . Innovations in theory . . . some going back to the first decade of our century have hardly ruffled the surface of what has become the stagnant pool of music theory. Arnold Schoenberg, Heinrich Schenker, Ernst Kurth, Paul Hindemith, Felix Salzer—all have expressed their dissatisfaction in one positive way or another with the tight closed systems of the 19th century, all have created other ways to reach an understanding of our heritage. Yet we continue with the ancient assumption that the teaching of counterpoint should be aimed solely at style imitation, Palestrina and J.S. Bach being the prevailing models. And the goal of harmonic analysis seems still to be a series of wearying demonstrations that Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven knew as much about chord syntax, inversion, and modulation as do our brighter students."

9"In Search of a New Pedagogy," in College Music Symposium, Vol. 8 (1968), pp. 109-16.

10William Thomson, "The Core Commitment in Theory and Literature for Tomorrow's Musician," College Music Symposium, Vol. 10 (1970), pp. 35-45.