I am sure that all of us, for whom the dedication to musicology represents the fulfillment of our lives, would like to see musicology grow without limits as we keep proselytizing for this most wonderful of all fields of studies until everybody on this planet obtains some basic knowledge of our endeavors. We are aware of the fact that we have come a long way from modest beginnings to the point where the term "musicology" has become fashionable, being used and abused as well: even movies with musicologists as protagonists have already been made. The growth of musicological studies in the United States in the last twenty years has truly been spectacular, giving a superficial impression that we were about to succeed in that proselytizing effort of making everyone aware of our work. The time has come to ask ourselves whether we have not actually achieved too much too soon and for us to remind ourselves of that saying that the surest way to become poor is to become rich as fast as possible.

Some six months ago, at a meeting of the Midwestern chapter of the AMS in St. Louis, I presented a paper on the future of musicological studies in the United States, as one man's point of view, discussing the very same points which I propose to raise today, namely to question the unlimited growth of our field of studies and of the proliferation of doctoral degrees at a rate which appears to surpass the national average growth in other fields of study. During the last few years the realities of life have made us face the fact that quite a few musicologists have been unable to obtain jobs, joining the ranks of the unemployed; and yet it is one of my contentions that, in spite of the growing number of people who call themselves "musicologists," there is in actual fact a shortage of good musicologists and an oversupply of less than qualified persons with Ph.D.'s in musicology.

I feel compelled to raise some of these controversial points, leaving it to the membership of this society to discuss them, so that after a thorough examination of projections for the future and of their alternatives a better understanding of the issues may emerge and help us chart the basic direction of our endeavors. Just as not one of us can predict his own personal growth and development (or his decline and decay!), I think that no one could have envisaged some twenty years ago the fantastically rapid proliferation of musicological studies in the United States. What appears to have transpired looks very much like an inflation which, according to economics, will probably lead to a recession.

Statistical data, as we all know, can be made to tell us anything which we wish to see, but at the same time statistics do contain data which we cannot ignore. But before examining the situation in our own field, let me refer first to an interesting article published in the Spring 1972 issue of the AAUP Bulletin.1 According to the data in that article, from 1861 when Yale became the first American University to grant a Ph.D. degree, through 1970, all American universities awarded no less than 340,000 doctorates. If averaged over 110 years this would mean that in each of those years slightly more than 3,000 degrees were awarded annually. The shocker, however, comes with the realization that more than one half, or 182,000 of these degrees were awarded in the last ten years of the period, i.e. between 1961 and 1970, as opposed to some 158,000 degrees in the first one hundred years. Furthermore, the projections for the decade 1971-1980 (and we are nearly one third through that period!) envisage at least another doubling of the number of degree recipients, the estimates ranging from 340,000 to 500,000. As may easily be seen, this proliferation would even further glut the apparently already saturated job market. If for any reason we were unaware of this phenomenon, it seems to me that it must be brought to our attention. While the preceding figures reflect the total situation in all fields of scholarly studies in this country, let us now examine the situation in our own field of musicology.

According to available information the first Ph.D. degree in music in the United States was awarded by Harvard University in 1905. By 1931, when Oliver Strunk conducted his examination of the "State and Resources of Musicology in the U.S." for the American Council of Learned Societies (published in December of 1932) there were only four recipients of the doctor's degree, and there were only seven schools with programs leading to the Ph.D. in musicology. A re-examination of these data by Cecil Adkins suggests that there were at that time already some five recipients of that degree and that only one school seems to have conferred the degree, suggesting also that the six other schools viewed the existence of such a program as an opportunity for future development. It was only in 1939 that we find these seven schools to have actually each conferred at least one doctorate in music.

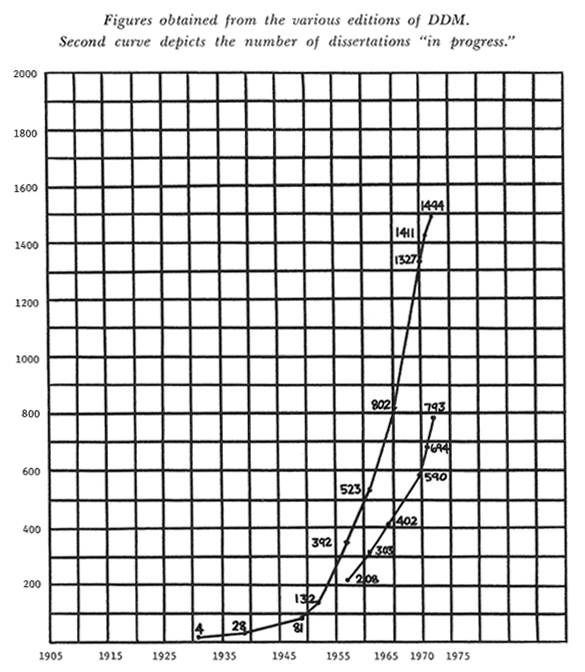

With the establishment of the first chair for musicological studies in this country, at Cornell, in 1930, the situation was bound to change rather rapidly; and let us remind ourselves also that in 1934, when AMS was founded, not all of the nine founders had advanced degrees. Yet the field of studies did grow and by 1952, or twenty years after Strunk's report, according to the first edition of Helen Hewitt's Doctoral Dissertations in Musicology, there were 132 completed doctoral dissertations. A breakdown of Miss Hewitt's data (prepared by Merellyn Gallagher and published in Student Musicologists at Minnesota, ii [1967]), and information graciously supplied by Cecil Adkins (including new computer print-outs as well as a check of all five editions of DDM and of its annual supplements) have enabled us to prepare the graph in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. NUMBER OF Ph.D. DEGREE RECIPIENTS IN MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES

On that graph the continuous line presents the cumulative number of Ph.D.'s in musicology and the second line presents the number of dissertations "in progress" for which data prior to 1957 have not been checked. For the years after 1970 I have examined the annual supplements and subtracted the number of completed dissertations and added titles which were listed for the first time to those that have previously been listed as being "in progress." This graph should therefore be viewed as a cumulative one. It should be pointed out that due to some changes in "bookkeeping" practices that the figures for the last six-to-eight years include some related areas and D.M.A. degrees. Yet even if there is an allowance for some percentage of the data to be off, the basic direction of the curve is unmistakable: while the number of recipients of the doctoral degrees is growing rapidly, the number of dissertations "in progress" is growing at an even faster rate. The Malthusian projection of overpopulation is raising its spectre, making us wonder whether we should not consider some of the principles of Zero Population Growth (ZPG) and then control additional proliferation of the Ph.D.'s, perhaps allowing each Ph.D. to produce only two other Ph.D.'s in his lifetime—under penalty of lobotomy.

I also realize that this graph does no justice to the actual state of affairs as it ignores the attrition due to various causes—deaths, withdrawals, retirements and the never-completed-dissertation. This graph has really only one way to go, and it will always point upward; and so the basic question remains—what do we do with the uncontrolled growth and proliferation of Ph.D.'s? Perhaps we should ask ourselves a different question—who needs the Ph.D. and why? It is possible for us to try to answer these questions and then to come closer to the root of the problem.

Ever since universities came into existence in the late Middle Ages the title of "doctor" has represented a sign of distinction for learnedness. But the degree of learnedness is something relative to the total body of knowledge within any given field of inquiry and scholarly pursuit. I recall reading not so long ago that the total body of knowledge accumulated by all generations of scholars and scientists until 1900 has literally doubled by 1950 and that by the mid-1960's it already tripled in size, partly due to advances in technology and partly to the growing number of persons becoming involved in research. If this newly acquired information is regularly incorporated into ongoing instruction of students, I would not doubt that a present-day Bachelor of Arts, and especially a Bachelor of Sciences could easily possess more factual knowledge than a Ph.D. of centuries past. An inevitable consequence of this growth should be that as time goes on there must be a continuing upgrading of requirements for the doctor's degree, and it is probable there that one of the roots of our problem may be hiding.

If an answer to the question "why" might be that the community of scholars wishes to bestow as a sign of distinction the title of "doctor" on someone for the quality of his learnedness and achievements in pursuit of scholarship, whether as an earned or an honorary degree, this is a valid reason which also poses an obligation on the recipient to continually maintain the degree of excellence which has in the first place earned him the respect of his peers. An answer to the question "who needs the degree," as I see it, is much more involved and complex. It would seem to me that if a person is truly dedicated to a field of study, this dedication alone as well as the work itself could provide enough satisfaction so that he would not care about a degree. Need I remind this audience that some of our best musicologists never obtained an advanced degree? Yet no one of us has ever doubted their being learned scholars, and we refer to their work as a matter of course.

As I see it, certain relatively recent developments at some universities in this country have been and still are responsible for the proliferation of doctorates. Among those guilty in this respect I include professional administrators. It has for a long time been taken for granted that faculty members at universities should be distinguished scholars, most of whom would have the doctorate. When in recent decades a number of state teachers' colleges "upgraded" themselves by being renamed as "universities," there was a clear case of the devaluation of the concept of a university as a focal place for pursuit of scholarship. Having become "universities" in name, but usually with the same faculty oriented primarily towards teacher-training, these schools took upon themselves to confer doctorates which, in turn, started proliferating themselves in all directions; for us, the most interesting is the D.M.A. (Doctor of Musical Arts) degree for performers. I submit that the institution of the D.M.A. degree represents another instance of the devaluation of the concept of a doctor's degree, contributing to its proliferation.

Professional administrators have supported this proliferation with their desire to "upgrade" themselves and their schools by refusing to grant tenure to excellent teachers, or to less productive scholars, or to master-performers simply because they lacked the title "doctor." There is no reason in the world why a master-performer on any musical instrument must have a doctorate in order to receive a tenured appointment, and there is no reason why the Master's degree should be viewed as insufficient for persons who have no scholarly ambitions or interests. In saying this, I am fully aware that I am swimming against a tidal wave, but I do feel an urgent need for the restoration of the dignity and respect for a Master's degree which should testify to a level of quality rather than to a number of credits alone. And one of the reasons why the curve on the graph has been climbing so rapidly is that many a "dissertation" and its degree is counted in it when according to the objective standards of scholarship it often barely approaches the level of a seminar paper at a self-respecting university where the pursuit of excellence continues. This leads us to that old saying that there are "degrees" and "Degrees." It is entirely possible that with this reference to "degrees" and "Degrees" we are coming perilously close to the crux of the matter of the proliferation of Ph.D.'s in musicology. Is there any way in which we may be assured of the quality of degrees as we are encouraged by the growth in quantity?

Some ten years ago the AMS had an "Advisory Committee on Graduate Standards," and at the annual meeting in St. Louis in 1969, the AMS "Committee on Curriculum and Accreditation" presented us with the now well-known "Guidelines for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Musicology." This attempt at a thorough examination of the status of the profession appears to have been pigeon-holed fairly quickly, and I am not aware of actions by either of these committees to have exercised any influence on subsequent developments.

Let us glance now at the number of schools offering Ph.D. degrees in this country. As already indicated, in 1931 Oliver Strunk found seven schools with programs leading to the degree. In 1961 Miss Hewitt listed 37 schools with such programs. Thus, statistically speaking, in the thirty years between these two listings, on the average one school per year was adding a doctoral program in musicology. The Adkins edition of DDM in 1970 records some 56 schools, or a jump of 50 percent in the number of institutions in ten years, or in other words showing that in the decade 1961-1970 on the average two schools per year were adding new doctoral programs in musicology. The data assembled by Adkins indicate that only forty-seven schools have actually conferred such degrees (in which case the one school per year proportion still holds); yet we also notice that some nine schools are embarked on the program, and it already exists even though by the time the last edition of DDM appeared they had not yet produced a Ph.D. recipient. If this ratio of growth were to continue, by 1980 alone there could easily be close to eighty institutions of higher learning in this country offering the Ph.D. program and producing additional degree-holders who, in turn, after getting settled in some job in a school, could likely insist on acquiring "status" by introducing more and more Ph.D. programs.

Another aspect of the growth of the number of institutions offering doctoral programs in musicology is that, according to statistics, an increase of 50 percent in the number of institutions leads to a doubling of the output of Ph.D.'s as well as doubling the number of dissertations in progress. If this growth-rate is projected to 1980, we can easily have close to 3,000 Ph.D.'s in musicology and anywhere between 1,000 and 1,500 dissertations in progress at that time. And if we are at this time already experiencing economic problems of considerable magnitude, what are we to expect to happen in less than ten years with twice the number of experts when the remaining period of time is far too short for the normal rate of attrition due to deaths and retirements?

This brings me to a recommendation which needs to be examined, discussed and thrashed out among ourselves: let us recommend a moratorium on the proliferation of the number of schools offering the Ph.D. program in musicology. This, I realize, is easier said than done. But even if this proposal were somehow implemented there would still remain the question of "degrees and Degrees," or to paraphrase it, of schools and Schools. So what can be done? It is obvious to me as it is to all of you that there is no way to legislate anything by the AMS and that we must seek alternatives.

One of these is the question of accreditation. I am not the first one to raise this point, as Barry Brook did it some years ago besides raising another question, that of the evaluation of faculty competence (among other criteria) if a graduate program is to be instituted. If the AMS were to assume upon itself the task of accrediting of institutions, I am afraid that instead of being viewed as humanists and scholars, we would most likely project the image of a guild not unlike the American Medical Association (AMA) or the American Bar Association (ABA) or some other professional group. I would also find it repugnant to apply the type of pressure that AMA, for instance, exercised in the 1930's when it withdrew accreditation from a number of medical schools in order to guarantee high income to its members. This whole matter of accreditation, nevertheless, deserves to be discussed at great length, and all of its ramifications need to be explored since it is entirely possible that the abuses of this approach may have a debilitating effect on further growth of scholarship. Besides, many of us are already familiar with the accreditation procedure of the NASM (National Association of Schools of Music) which, as far as I know, has become a "mutual admiration society" rather than a check on the quality of instruction.

Let me also say that so far, even without the accreditation, the general level and competence of the majority of American Ph.D.'s in musicology is quite high, and the quality of the best of the incoming graduate students seems to be getting better every year. But the word "majority" implies also the existence of a "minority" that, let us be frank about it, is not necessarily a credit either to the institutions from which they received their degrees nor to the field of musicology. This brings me to Barry Brook's point of the evaluation of the competence of individual faculty before the institution of graduate programs at a university. Regardless of what has transpired so far, we can start right now tightening the standards and raising them each year, closing thus the loopholes for the "minority" to pass through. If we talk about tightening of standards, this is again a matter of personal interpretation and by no means a foolproof process. The well-known "Guidelines" and statements by Professors Ringer and Stevens are admirable though minimal standards, since not one of us, in all sincerity, would dare promulgate some maximum standards for the very simple reason that most of us would feel uncomfortable with such standards when perhaps 99 percent of us could not measure up to them. Yet in spite of the possible inability to measure up to the highest possible expectations, a good many of our members are valued, valuable and productive scholars, expressing themselves in publications and exercising strong influences through the excellence of their teaching.

The very fact that the "Guidelines" suggested minimum standards creates the possibility for production of the "minority" of "less-than-high-quality" degree recipients in the future, and this is, presumably, the price that we as a democracy have to pay for growing larger as a scholarly group. To many a student of musicology, I have been saying for years that for the remainder of their lives it is not the degree that will count, but what one does and produces afterwards that will in the long run be far more important than the accumulation of degrees. How many of our best known concert artists have taken the trouble of getting a D.M.A. degree? Yet we honor them and respect them, while many degree-carrying artists seek refuge in schools administered by professional administrators, satisfying the desire of the latter for "doctors" on the faculty. And if you come to such an institution in which everyone insists on being addressed as "Dr. So-and-so," you might easily have the feeling of being in a hospital rather than in an institution of higher learning concerned with the intellectual and spiritual achievements of mankind.

The growth of colleges and universities has already created multiversities, and the proliferation of doctorates has already led to some talk about "super doctorates." If instead of such a talk we reach the point where we can agree on a true tightening and raising of scholarly standards for the doctorate and where we view the Ph.D. degree as a sign of distinction rather than as a passport to tenure, we will make an important step in stemming the tide of the proliferation of doctoral degrees. How might this be achieved? One possible way might be the system of outside examiners already practiced in some countries. For each doctoral examination and defense of the dissertation, there is an outside examiner, usually an internationally recognized scholar from another university, who is invited to help in the evaluation of a candidate. As far as I know, nowhere has this system been interpreted as a slighting of the scholarly abilities of a school's faculty but is viewed as a check against self-delusion. It does involve some expense on the part of the university inviting the examiner but also serves as a constant reminder of the necessity for quality, since it is unlikely that a dissertation-advisor would risk exposing his incompetence to a famous colleague from outside. Thus, even without an attempt at evaluation of individuals, the burden of proof would be shifted to the conscience of the faculty. This is just a thought, but if this idea were to materialize responsibly in the United States (and not become transmogrified into one incompetent person inviting another from outside!), then it would not be bothersome to us to contemplate the existence of even one hundred schools offering the Ph.D. degree, since a constant check on the quality could be maintained.

As I see it, the existence of a Ph.D. program should not be interpreted as an obligation on the faculty to "produce" degree recipients just because the program exists on the books. The existence of the program is an opportunity, not a compunction to produce results at any price. This, I admit, may represent something of a problem, especially in state-supported institutions which, unfortunately, seem to tend to view the degree as a "prize" for the number of credits rather than as something earned for the attainments worthy of that degree. I also realize that this viewpoint would be the most difficult to present to university administrations. Very shortly after reading my paper in St. Louis, last April, it was brought to my attention that in one of the Midwestern schools the administration insisted that its Music Department "produce" at least three Ph.D.'s per year or the program would be abolished. This, it seems to me, is the wrong way of tackling our dilemma. I hope that a discussion among the members of the AMS may provide us with fresh insights and ideas for a more realistic appraisal of our situation and suggest some guidelines for the future without jeopardizing a salutary growth in the discipline of musicology. I also hope the discussion will explore ways to avoid over-production which could only contribute to the glut and economic catastrophe of those whom we are presently training in the field of musicology and to whom we are transmitting the basic humanistic values found in this exciting field of work. At a time when professional standards are being upgraded seriously in areas like medicine and the sciences, we cannot permit an erosion of standards in the humanistic discipline of musicology.

This paper has not brought up anything that has not already been known to most of us, and it was not my purpose to come up with specific recommendations for a needed improvement of the process of studies in our field except to point out some trends and make us aware of the statistical aspects of the growth in our field. Nevertheless, an exhortation for tightening of our own scholarly standards is needed periodically as well as an appeal to the conscience of each one of us. And last, but not least, I hope that with the quantitative growth of musicology, its quality is going to keep going higher and thus make our calling even more respected in days to come.

1Dael Wolfle and Charles V. Kidd, "The Future Market for Ph.D.'s," AAUP Bulletin, Spring, 1972, pp. 5-16; reprinted from Science, CLXXIII (1971), pp. 784-793.