One of the ubiquitous problems which confronts the average college music professor in a liberal arts setting is the confrontation of the musical world with that of the liberal arts, i.e. the humanities. Though we pride ourselves on being part of the humanities, we are still in a world foreign to most of the humanists because of their lack of any real musical education, or because we have been so specialized due to the inherent demands of our profession and somehow only received a whisper of a humanistic education, i.e. the required general education requirements at our respective alma maters. The music requirement which comprises general education requirements at institutions of higher learning in the United States is usually relegated to an appreciation type of course which carefully avoids the problems in teaching music or even in learning to appreciate music, and invariably, the chronological-historical approach is used with the usual amount of "drop the needle" tests, etc. Lately, the problem has only been augmented by the inclusion and sometimes assimilation of world music into the courses which still avoid the problem of studying music in depth for the general student.

There is no doubt that we as music professors are faced with almost insurmountable problems when teaching a music course within the framework of a general education program. First, we have students who usually do not read music, unlike the teachers in literature, history, political science, and even foreign languages (unless the language is one other than that which uses our alphabet). The second, and probably one of the main obstacles, is that most of the students are in the class under duress and see no connection that the music course might have with their own particular fields or with the totality of knowledge, particularly if it is part of the cafeteria approach to general education, e.g. a certain number of units in music, science, English, history, etc. Then we demand, third, that the student use one of the senses which he is unaccustomed to using—hearing. Two physical problems—seeing (reading music) and hearing—along with the coercion of the general education requirement impede any professor's efforts on the student's behalf as well as on his own.

These natural and formidable obstacles, common to all music courses which form a part of any general education requirement, are just the initial problems. Where the humanities deal with concrete human ideas, ideals, meanings, and emotions centered in human experiences, the musician has the problem of correlating the music in an interdisciplinary fashion. Other than with a few concepts historically, biographically, and perhaps musically, how does the college professor conquer this problem? Undoubtedly, there is a huge epistemological problem when dealing with music in the humanities, for materials are sadly lacking except for a few well-known sources such as Suzanne Langer and sundry works.1 The purpose of this article is not to explore those epistemological problems, for that would take more space than allotted. Suffice it to say that the language problem does exist, and the music professor in his past studies has not met it in his own work or incorporated it with his own teaching. This factor alone is one of the major inhibitors to the good teaching of music in a general education course or even in a music curriculum. Unfortunately, the problem has been carefully avoided, sidetracked, and essentially ignored by most institutions and music schools.

When a new humanities program called "The One and the Many" was initiated by Dominican College three years ago and funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities beginning in 1973, all of these problems were taken into consideration in the creation of the program. Although there are some puzzles yet to be solved, the program at this early stage in its history is a resounding success for the College, for the faculty, and most of all, for the student. In contrast to Dominican's former lock-step method of fifty-six required units during the first two years of a College student's life, the new program requires only fifteen units of Humanities from the student which he may elect to take at any time during his four years at the College.

The purposes of the program are varied and many: to expose the student to an in-depth study of a particular theme, period, or problem, central to the humanistic tradition, with the idea that he can apply those solutions to comparable problems; to deal with the human experience and not necessarily the accumulation of a certain amount of data or information; to teach the student to seek methods and ways of solving human problems or experiences; and to involve the College totally in the program with an emphasis upon faculty development.

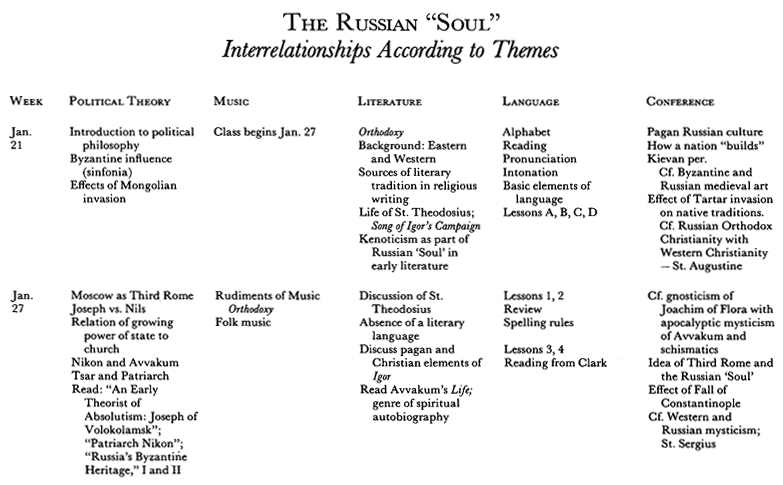

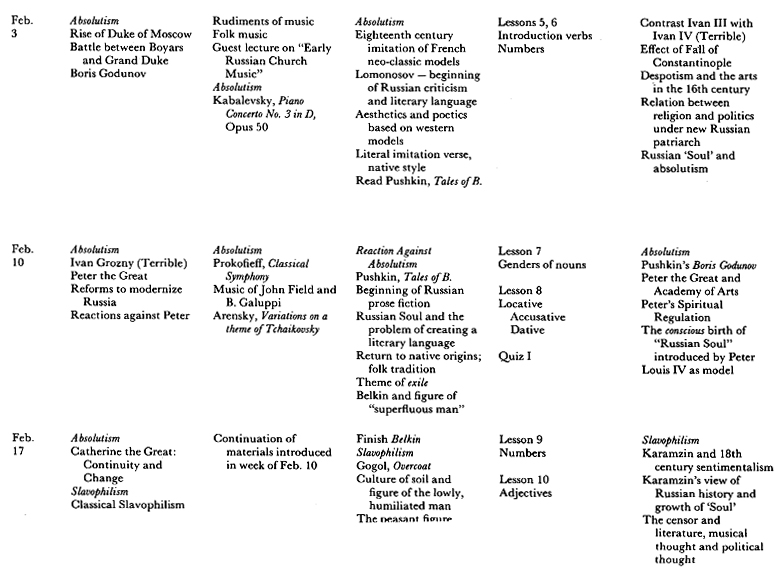

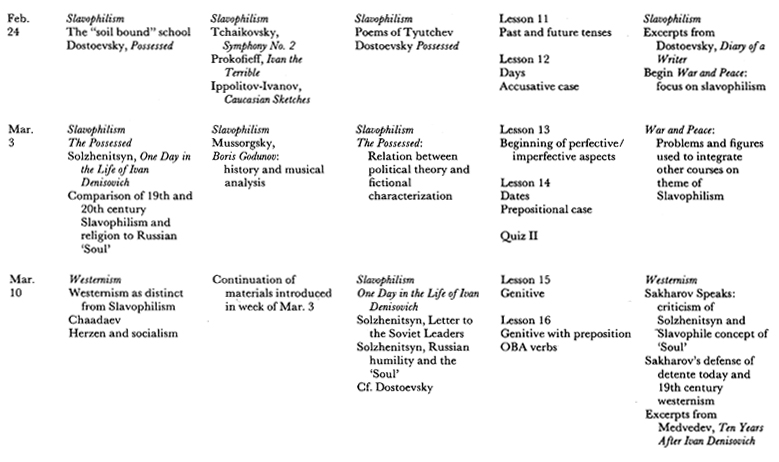

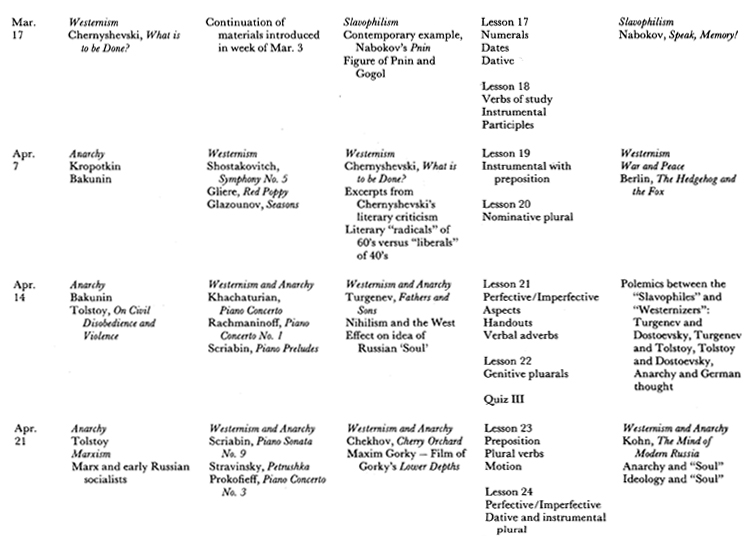

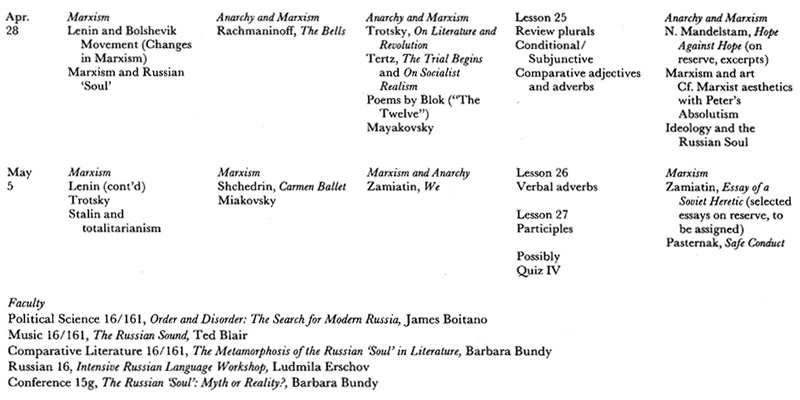

The Humanities Colloquia,2 as they are called, are given one or two each semester, and they range from "The American Dream," to "The Russian Soul," and "The Greek Mind: in Pursuit of Excellence." Since I participated in "The Russian Soul," I shall relate that particular one in detail. It, like the others, is designed for no more than fifteen students with each faculty member attending as a student one or more of the courses within the colloquium. This last factor has been greatly aided by a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and in essence relieves the professor of one course in his department so that he can attend and participate in another course in the colloquium. The courses in "The Russian Soul," all three units each, are:

Political Science: Order and Disorder: The Search for Modern Russia

Music: The Russian Sound?

Comparative Literature: The Metamorphosis of the Russian Soul in Literature

Russian: Intensive Russian Language Workshop

Conference: The Russian "Soul": Myth and Reality

All of the courses are intensely interdisciplinary in purpose, but the conference assimilates and synthesizes all the disciplines into one. The problem is stated by the leader of the conference, Professor Barbara Bundy (and director of the Colloquia Program in the Humanities):

. . . The myth of the Russian "soul"—that Russia has a "peculiar nature"—has its origins in the separation of Russia from western Europe under Mongol rule. The soul was articulated as a political and psychological reality when Peter the Great had to shape a nation out of a tradition that lacked a basic historical idea in the early eighteenth century; the "soul" became a distinctly native Russian myth that the Russian peoples could claim as unifying them. . . . examine in depth the belief of the Russian peoples in the mystical power of their native soil, their bloodline and the messianic powers they believed the Russian Orthodox Church had—beliefs that have been a chief source of personal and national identity for Russians and which are still operative today, in highly transformed ways, in Soviet ideology.

The function of the conference is to interrelate the works of the colloquium courses in relation to the six problems and themes that form the focal point of the colloquium as a whole: "orthodoxy," "nationalism," "absolutism," "Marxism," "anarchy," and "westernism." These problems will be explored in depth in the Music, Political Science, and Literature courses and brought together in the Conference.

During the course of the semester, all of the above aims were patiently and sometimes arduously probed. The entire colloquium was supplemented by guest lectures on Russian painting and architecture, Russian icons, the Orthodox Church, and Soviet art. Students were encouraged to attend functions in the San Francisco Bay Area related to the colloquium—e.g. concerts by Mstislav Rostropovitch and Galina Vishenevskaya, Russian film series at one of the local San Francisco theaters, Dominican concerts which featured Russian music on the programs, the San Francisco Symphony which had several programs with Russian compositions on them, the Russian Orthodox Easter Mass, and of course to investigate and to participate in one way or another in San Francisco's rather large Russian community.

Although there were times when the faculty deviated from the planned time chart, the accompanying chart was followed quite carefully the greater part of the semester.

None of the faculty had any illusions about how difficult both the language and the music would be for the students, because of the innate difficulties in learning a new alphabet in each. Too, one of the aims of the colloquia was that the subject matter must be studied in depth, so that the music course had a two-fold problem in teaching the language and probing Russian music in depth, all of which had to be accomplished in sixteen weeks!

The procedures adopted to assure this accomplishment were quite simple and worked well according to a retrospective view. Four piano majors from the Department of Music were enlisted to teach piano lessons to the seventeen students who had no previous background in piano or reading music (out of twenty-two students—the courses are open to the general student, but only fifteen must take the combined colloquium). Then, the first six weeks, rudiments were covered as part of the class; and at the end of each session, all students had to play the piano for the instructor. Musical structures, terms, keys, and the general theoretical system were covered and learned by the students. Even modern compositional techniques were investigated. The study of Russian music was begun immediately; and during the course of the semester, many works were listened to and three major musical works were investigated in depth: Petrushka by Stravinsky, Boris Godunov by Mussorgsky, and Symphony No. 5 by Shostakovitch.

What this in-depth investigation meant was that the works were analyzed and listened to, and then conclusions about their "Russian-ness" as well as their aesthetic values were discussed. The last, as we all know, is the most difficult. Since Professor Bundy and I both knew the difficulty of explaining music to a group of non-musicians who were accustomed to verbalizing all aspects of life, we had team-taught a course on the Aesthetics of Literature and Music the previous semester. Temporal relationships, space, unity, organic growth, movement in music, performance of music, common symbolic meaning, commanding form, emotive devices, and structural semblance had all been investigated in depth; and these now proved useful in explaining Russian music. Many a class session ended up with the explanation and discussion of these various aesthetics of music and other kinds of art.

At the conclusion of the semester, the class had learned to interrelate the different courses, had learned that culture is an organic development, that the process of creation is one of confusion to clearness, that music is a language of communication, that music encompasses feelings, and that, as Suzanne Langer stated so well, "Music at its highest, though clearly a symbolic form, is an unconsummated symbol." The students in the colloquium had by the end of the semester drawn their own conclusions as to how the Russian "Soul" had permeated all aspects of Russian music, even that of the exiles such as Stravinsky and Rachmaninoff.

The epistemological results are mentioned first, for it is assumed that the reader understands that the musical traits of Russian music were discussed and examined in detail: the rhythm, modality and minor keys, the coloristic orchestration, the Slavophilism which prevails at all times, nineteenth-century realism as opposed to socialist realism of the twentieth century, how the Russian language affected certain attributes of the musical style, the predilection for programmatic rather than absolute music, and how Mussorgsky's ideas about music were absorbed and adopted by Soviet musicians.

The entire experience of the semester was unlike anything this author had ever experienced—a luxury beyond a musician's or a scholar's dreams—to study in depth through the history, literature, music, language, political theory, and an entire culture to see how a people think, believe, and most of all how they compose and enjoy their music.

1Langer, Suzanne K., Feeling and Form (New York: Charles Scribner, 1953).

2A "colloquium" is a 12 or 15 unit interdisciplinary cluster of discipline-based courses which are correlated by a set of common problems and themes (decided upon by the faculty members involved) integrated by a seminar course (emphasizing discussion) called the conference.