Many of the ideas in this article were formulated with AnneMarie de Zeeuw in the preparation of Sight-Singing and Related Skills, de Zeeuw and Foltz (Austin, Texas: University Stores Inc., 1973).

To anyone who is aware of the content of the college level sight-singing class during recent years, it has become apparent that a number of changes have taken place within the structure of this standard music course. The changes which come to the fore deal with the type of literature covered and a general shift in techniques used in developing sight-singing skill. Although this transformation has taken place primarily to accommodate trends in twentieth-century literature, a shift in attitude has taken the course from the confines of an academic discipline to a more functional attitude, shared with many pedagogues of today. The primary purpose of this article is to concentrate on the shift of techniques used in the current sight-singing class which serve the needs of today's student.

For centuries, tonal melodies have been the basis for material covered in sight-singing classes. Vast pedagogical resources were developed which have proven quite successful in teaching the singing of tonal music. One of the most popular of these methods is the "movable do" system, in which solfège syllables are applied to scale degrees. This system and the "fixed do" system (solfège syllables applied to particular pitch classes) have become so popular that it is quite common to refer to sight-singing classes as "solfeggio." Certainly, there could be little argument against the usefulness of solmization or the benefits it can manifest today in achieving tonal orientation. The need of the present day sight-singing class is not necessarily for an abandonment of any traditional techniques, but rather for additional pedagogical techniques which would accommodate the singing of twentieth-century literature. It must be understood that these comments are not designed to abolish preexisting ideas but rather to supplement and strengthen the sight-singing class of today.

One of the primary problems faced with a class based entirely upon the "movable do" or "scale degree" method is that, although this can aid tremendously with tonal music, it may prove to be of little use for nontonal music. A "fixed do" system has shown some benefits with nontonal music in giving the student an aid toward pitch recognition, but other techniques need to be developed in order to achieve proficiency in all music literature.

The most valuable new tool is an orientation toward intervallic thinking. A significant amount of time needs to be spent on this concept, especially in the early stages of sight-singing, so that the student can be made aware of intervallic relationships within a piece of music, whether it be in sight-singing or on the student's principal instrument. Facility in instantaneous recognition of intervals should be incorporated into all phases of sight-singing, for deficiency in perception is often the impetus for an incorrectly performed interval in a tonal as well as a nontonal work. Once again, intervallic awareness does not mean an abandonment of tonal orientation or any other analytical aid (where applicable) but rather an ever-persistent intervallic consciousness which can be instantaneously called upon in order to assist in singing a given piece of music.

Concentrated work on simple visual recognition of intervals should precede any drills directed toward intervallic thinking. Through preliminary practice the student will then be able to recognize intervals faster than he can verbalize them. In order to lessen the monotony of this type of drill, variants such as the use of visual aids are suggested. For example, a series of intervals are placed on a projector with only one interval shown at a time so the student's VRIPS (Visual Recognition of Intervals Per Second) can be measured. Although these exercises are rather mechanical and unmusical, they are necessary in order to achieve the needed visual facility in intervallic perception.

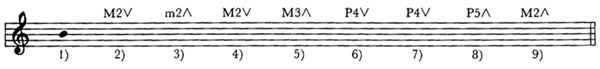

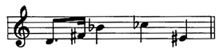

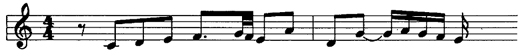

An early exercise should accompany the preceding study in the singing of a given interval on command. If an E-flat were to be given, for instance, the student would then be required instantly to sing a perfect fourth above the pitch. The following exercises are designed as additional introductory material into intervallic thinking, while giving enough diversity to avoid monotony. Below are two interval chains which might be practiced until the student can develop unquestionable fluency.

Ex. 1

Ex. 2

Another classroom exercise, based on this drill, is the performance of interval chains by giving a starting pitch and having each student sing a given interval based on the previous pitch.

At an early point in the student's preparation, work with interval classes is recommended. It has been customary to introduce intervals according to their span, beginning with the minor second. This introductory procedure has its merits, but brings with it some disagreeable orientations. The chief objection is that this tends to orient the student toward the smaller intervals creating apprehension about the larger intervals. This orientation along with the problem that some students have with intervallic complementation (i.e., confusing a major third for a minor sixth, perfect fourth for perfect fifth, etc.) necessitates the need for early work with interval classes.

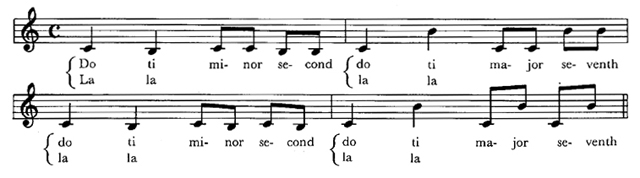

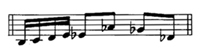

An interval, its complement (inversion), their compound forms, and their enharmonic equivalents together comprise an interval class. Interval classes (abbreviated I.C.) are numbered in accordance with the number of semitones contained in the smallest representative of each class. For example, I.C. I (Interval Class I) consists of minor seconds (augmented primes), major sevenths (diminished octaves), minor ninths, and so on. When starting work on each interval class, it is suggested that an introductory vocalise be thoroughly practiced beginning on a variety of pitches, such as the accompanying vocalise for I.C. I.

Ex. 3

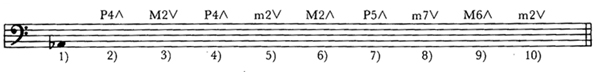

After the student has become familiar with the vocalise, he should begin exercises with undetermined rhythm which concentrates on that particular interval class. Example 4 concentrates on I.C. III.

Ex. 4

This type of exercise should be followed by exercises with determined rhythm, as shown in this example involving I.C. IV.

Ex. 5

Although undetermined rhythmic exercises are sometimes appropriate, it should be noted that exercises such as the preceding are important not only in developing musicianship, but also in the coordination of intervallic thinking with other musical considerations.

After the student has mastered these exercises, it is recommended that work be done with atonal melodies. These examples may be obtained from the literature or composed for this purpose, the point being that they should rely almost entirely upon intervallic thinking. The following are some examples of this type of exercise. It is best that the student develop the habit of analyzing the intervallic content before the example is sung.

Ex. 6

Ex. 7

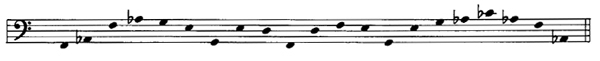

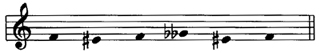

A difficulty that is frequently encountered with a great amount of twentieth-century literature is the problem of enharmonically equivalent intervals, as shown in the following example.

Ex. 8

Periodic practice on drills in enharmonic recognition should therefore receive attention. Notice that in the given example, all pitches are enharmonic equivalents, but it is recommended that a nonequivalent be added to the group to keep the student alert. A suggested drill is to project a group of five pitches with all except one being enharmonic equivalents. Allow the student approximately five seconds to look at these pitches and eliminate the pitch which does not belong to the group.

One difficulty in gaining intervallic proficiency is that an extensive amount of drill has to take place. Even though this proficiency will permit greater facility in reading music from all periods, the instructor needs to maintain a considerable amount of variety within the exercises. Three supplementary examples have been included to demonstrate further drills which give extended variety to the same goal. Besides strengthening intervallic orientation, these exercises, some of which are taken from the literature, enhance other musical concepts.

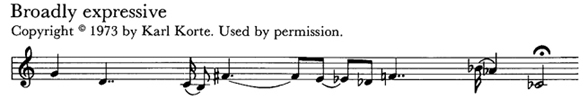

With the first example, by Karl Korte, a row is to be found and then abstracted with undetermined rhythm. First the row should be sung, then the inversion, the retrograde, and the retrograde inversion. It is suggested that several different transpositions of each form of the row be sung. The stress is on transposition through intervals, as opposed to clef substitution.

Ex. 9. Korte: Alternate Rows I

A further recommendation is that fugue subjects be used, from which a real answer is to be sung. Although inversion and retrograde do not always occur or suit a particular fugue subject, they may be attempted to add further variety.

Ex. 10. Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I

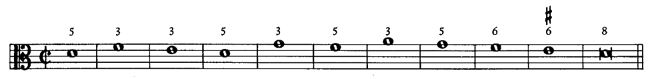

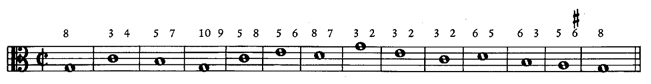

The next suggested practice is an excellent device for strengthening intervallic perception. These two examples are taken from Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum, with the cantus firmus provided in written pitches and the counterpoint in arabic figures. Figures above the staff indicate intervals to be sung above the cantus firmus, while those below the staff indicate intervals to be sung below the cantus firmus. The student can play the cantus firmus and sing the counterpoint. These exercises can also be performed as ensemble drill.

Ex. 11. Fux: Gradus ad Parnassum

Ex. 12. Fux: Gradus ad Parnassum

Only after the student has developed some proficiency with many of the drills dealing with intervallic orientation should he be allowed to do extensive work with pitch sets, defined as any designated group of pitch classes. Traditionally, many sight-singing classes have started at this point, namely, the first work covered was the singing of major and minor scales. This is not to deny the benefits of work done on pitch sets, but the manner of approach to such material is important. The danger in early concentration on pitch sets without any sort of intervallic work, whether it be a major scale or an arbitrary four-pitch set, is that this may induce a type of rote singing in which the student has no intervallic orientation whatsoever. It should be stressed that this problem can occur with a twentieth-century example based on a four-pitch set as easily as it can with a folk tune based on a major scale.

If concentrated work on pitch sets is developed with intervallic thinking, then such work will be more beneficial. Being conscious of the pitch set of a work is a necessity but it must be coordinated with intervallic awareness.

Working with pitch sets should not be limited to major and minor scales. Drills may be expanded to include the church modes, pentatonic scales, whole tone and chromatic scales, as well as arbitrary three, four, five, or six-pitch sets. If the student is intervallically aware, this expansion will be quite accessible. As in the work with interval classes, it is recommended that work with pitch sets begin with exercises of undetermined rhythm, followed by works from the literature or specially composed examples illustrating a particular pitch set.

Without question, the most frequent drill should be the singing of excerpts from a diversity of repertoire. Not only does this contribute to the student's knowledge of music literature, it also confronts the student with one of the primary functions of sight-singing—that is, the skill to vocally produce a given piece of music, whether it be Bach, Schoenberg, Gregorian Chant or folk song. Sight-singing is much more than an academic discipline; it is a necessary component in the equipment of every musician. It is an important and convenient means of musical communication for both the teacher and performing musician.

If we consider sight-singing a vital part of a comprehensive musician, it seems out of step for this skill to be limited to any period or particular type of music. Perhaps these suggestions may be integrated with existing pedagogical techniques as we strive to fulfill the needs of our would-be comprehensive musicians.