During the last decade the Educational Commission of the States has sponsored an ongoing project entitled "The National Assessment of Educational Progress."1 Developed in collaboration with the National Center for Educational Statistics of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and carried out with additional funds from the Carnegie Corporation and the Ford Foundation's Fund for the Advancement of Education, this information-gathering program has been surveying the educational "attainments" of 9-year-olds, 13-year-olds, 17-year-olds, and adults between the ages of 26 and 35.

Ten subject areas were selected by NAEP for study: Art, Career and Occupational Development, Citizenship, Literature, Mathematics, Music, Reading, Science, Social Studies, and Writing. Two of these areas have been surveyed each year, and all have been scheduled for reassessment five years after the initial assessment has been completed to determine trends.

Work on the music assessment began in 1965 when a group of educators, scholars, and lay persons convened by the Educational Testing Service were asked to formulate objectives which, they felt, "Americans should be achieving in the course of their education." They agreed that, since music is, or can be, "a personal aesthetic experience," the primary goal of music instruction should be aesthetic education; that is, it should help the individual achieve aesthetic experiences through involvement in music.

On the face of it, the success of a program dedicated to aesthetic education could be measured by the number, degree, and kind of aesthetic experiences achieved by the individuals enrolled therein. Unfortunately, it is a very difficult problem to define and to assess such experiences, much less set standards for them.

The group next considered the fact that an aesthetic experience in music generally does not come about unless the person undergoing that experience has developed some sensitivity to music prior to the event. Consideration of sensitivity per se soon led to the realization that it too is a concept which defies both easy definition and conventional evaluation.

A rational basis for making an assessment in music was perceived only after the cognitive development, the psychomotor skills, and the affective experiences which presumably underlie sensitivity had been examined. The group concluded that by measuring an individual's knowledge of music, his ability to perform music by whatever means, and his attitudes toward the various kinds of music available to him, they could extrapolate to musical sensitivity itself. Then through the acquisition of data concerning the sensitivity of thousands of subjects, they might gain insight into the progress being made nationally in music.

Accordingly, a plan was drawn up and reviewed by still another group which endorsed its underlying premise and structure. The plan was then passed on to the test makers, whose work was in turn examined by subject matter specialists and measurement experts to determine its appropriateness to the task at hand. Finally, during 1971 and 1972 a test consisting of 141 items was administered as a whole, or in part, to a randomly selected stratified sample of 80,000 youngsters, teen-agers, and adults drawn from the Northeast, the Southeast, and the Central and Western regions of the United States including Alaska.

The data generated by this gargantuan operation was initially compiled in terms of the age groups listed above. It was then re-examined not only in terms of the sex, the racial identity, and the educational levels of the parents of the individuals who took the test, but also in terms of the type of community and the region in which they resided.

In March 1973 some of the initial findings of the National Assessment in Music were released to the press by the public relations department at NAEP headquarters. Taken literally they suggested that the musical attainments of the citizens of this country are far lower than what might reasonably have been expected. Newspapers quickly seized upon the more sensational aspects in the press release and gave them wide publicity. Even so respectable an educational journal as School and Community couldn't resist publishing an article in its November 1974 issue entitled "I Hear America Singing, Badly?" The unnamed author gleefully reported that not more than 70% of adults were able to sing "America" with an accompaniment successfully, and that less than 15% could read even the simplest musical phrase correctly. He let his readers form their own conclusions, but the inescapable inference to be drawn seemed to be that the average American is a musical idiot.

To music educators the publication-without-interpretation of such findings appeared at best to be irresponsible and at worst a deliberate attempt to discredit the whole profession. Charles H. Brenner, President of MENC, replied to such detractors in an article entitled "Dough-re-mi," published in the March 1975 issue of the School Board Journal. In essence his argument was that results obtained from a random sample, however poor, ought not to be used to dismiss the fine work being done in many schools throughout the nation. He cited a number of outstanding elementary and secondary music programs and concluded that they would be maintained and even extended provided that those charged with financing public education kept the dollars coming.

To the credit of the test makers, steps were taken even as the furor raged to provide the kind of reporting and interpretation which would make for ethical journalism. In their official National Assessment in Music publications,2 which were issued between 1974 and 1975, they scrupulously avoided making sweeping generalizations from limited data and confined their discussions to the meaning and apparent significance of specific findings.

They also called together a distinguished panel of music educators to discuss the implications of the findings for their field. This group consisted of Paul Lehman, then Professor of Music Education at the Eastman School of Music; Jo An Baird, a Music Specialist with the Boulder, Colorado, Public Schools; William English, Professor of Music at Arizona State University; Richard Graham, Professor of Music and Director of the Music Therapy Program at the University of Georgia; Charles Hoffer, Professor of Music at Indiana University; and Sally Monsour, Professor of Music Education at Georgia State University. They met in January 1974 and their deliberations were subsequently published as a separate volume3 along with the other reports on the Assessment in Music.

Since 1975 the press has turned its attention to other educational scandals, and most of the music teaching profession has ignored the Assessment in Music. This neglect, which is due in part to the voluminous size of the official reports, is unwarranted, because the findings in music are relevant to the professional activities of everyone associated with the educational enterprise.

For the first time music educators have some measure of the effectiveness of school music programs that is above and beyond that afforded by the norms established by the standardized tests of music achievement.4,5 College professors, also for the first time, have some indication as to the performance skills, the technical knowledge, the acquaintance with musical literature, and the attitudes possessed by many non-majors who do, or should, form an important part of the student body in those departments which seek to engage the support of the whole campus. Most important of all, both groups now have the facts necessary for the development of more realistic views concerning the magnitude of the task of providing for mass education in and through music.

THE FINDINGS DESCRIBED AND INTERPRETED6

The NAM test sought to evaluate the musical attainments of a random sample of the American population by examining each member thereof in terms of his skill in musical performance, his knowledge of musical notation and terminology, his ability to recognize instrumental and vocal media, his familiarity with music history and literature, and his attitudes toward music. Each of these areas was subdivided into several parts as suggested by the topic and the philosophy of the test makers.

The section devoted to Musical Performance represents a departure from that which is usually associated with this term. Instead of limiting the inquiry to the more obvious manifestations of performance such as membership in the band, the chorus, or the orchestra, the test makers broadened it to include performances of every kind ranging from the commonplace to the esoteric. They felt that the layman's performance of simple songs and his playing of folk instruments was as significant as the amateur's best efforts in a more formal setting. Participants were, therefore, tested not only to determine the vocal and instrumental abilities they possessed but also to discover the degree to which they had mastered certain musical skills which underlie these abilities.

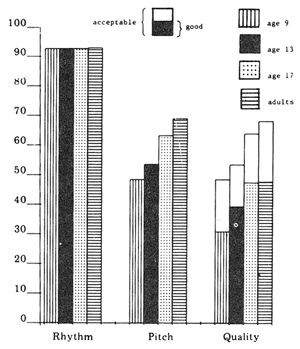

EXHIBIT 1. Percentages of acceptable overall performance on Exercise 1B, part A, "Singing 'America' With Accompaniment."

Commencing with Exhibit 1, we see that the vocal performance with an accompaniment of even the simplest and most widely sung of songs, "America," is fraught with peril.7 While comprehension of its rhythmic structure is not a problem for the vast majority, the reproduction of the melodic structure was another matter altogether. Pitch accuracy improves with age, schooling, and experience, but an "acceptable" performance is achieved by slightly less than 70% by the time adulthood is reached. Another exhibit, not reproduced herewith, demonstrates that this level of accomplishment declines to 60% when the accompaniment is withdrawn from the testing situation. We may ask, what does this mean?

The panel agreed that cultivating the ability to sing has long been one of the highest priorities of music education. At the same time Charles Hoffer noted that in reality many children got very little music training, since in 80% of the schools, music is not taught by music specialists, but by generalists, many of whom are woefully ill-equipped to do the job.

I would like to add two comments. One is that it is of the utmost importance when studying the Assessment's findings to bear in mind that a true random sample drawn from a nationwide population will inevitably include a number of individuals who have received no training in music whatsoever because, as will be seen later, music was not and in many instances continues not to be offered by the schools which they attended. The vocal skills of these persons, or the lack thereof, must affect the national average adversely. Thus, these findings probably reveal as much about the extent and quality of educational opportunity as they do about the musicality of the people.

The other is that the singing of solos is not much cultivated among children even in schools where music is taught by a specialist, because of their shyness about their voices. Boys, particularly those in the midst of voice change, are sensitive about singing alone. To do so at the request of strangers is beyond the pale. The test makers must frequently have found themselves in situations where to obtain the measurements desired they had to employ self-defeating procedures.

The test makers next asked the participants to repeat unfamiliar musical patterns, that is, simple material derived from the realm of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic dictation. The performance levels manifested in the first two categories here named were clearly inferior to that of the third. For this reason I will limit my discussion to the ability to repeat the rhythm pattern which has been annotated as part of Exhibit 3.

EXHIBIT 3. Percentages of acceptable performance on Exercise 1D, "Repeating a Rhythmic Pattern."

Over 60% of the 17-year-olds were successful in carrying out this task; the 9-year-olds were notably unsuccessful. Many of those who failed rearranged the pattern of eighth and quarter notes, demonstrating thereby poorly developed musical memory, inexperience, or both.

The panel agreed that the development of musical memory, which lies at the heart of such dictation work, is of considerable importance, since the ability to remember musical lines is part of the learning process. Paul Lehman pointed out that this skill is crucial because "music exists in time." Sally Monsour observed that children were not being prepared to solve the kinds of questions being asked in this part of the test, since most programs are song-oriented, rather than geared to the manipulation of the formal elements of music.

For my part I would agree with Sally, but I would add a qualifying statement, "except in those elementary schools which make a serious effort to include the Orff and Kodaly methodologies in their music programs." The aim of these systems is the development of juvenile musicianship; and children trained through them would, in all likelihood, be successful not only with the rhythmic problems but also with the melodic and harmonic ones as well. Unfortunately, the incorporation of these international "breakthroughs" by American pedagogues into their own practice is not as widespread as the attendant publicity would suggest. Furthermore, they were unknown on this side of the Atlantic when the adults in the sample attended elementary school.

Given the average American's interest in jazz, the findings reported in Exhibit 4 regarding his ability to improvise are interesting.

EXHIBIT 4. Percentages of acceptable performance on Exercise 1G, "Improvising a Rhythmic Accompaniment."

Individuals were asked to invent a rhythmic accompaniment to a slow jazz selection that was performed on tape by piano and voices. Children were given bongos to play, older participants a briefcase as a sounding board. The outcomes of this exercise, which are inconsistent with those reported in Exhibit 3, are impressive until one listens carefully to the sample performances recorded on the demonstration cassette.8 The so-called improvisations are very crude and the test makers deemed the various performances acceptable if the participants merely kept the beat. At best only 20% of those tested succeeded in offering rhythmic embellishments which rightly could be called creative contributions to the overall effect.

The group of experts disagreed on the priority given to improvisation skills. Several members felt that it did not have the priority that singing and other activities had. Charles Hoffer stressed that the generalist teachers in whose hands music instruction is most often entrusted in the elementary schools were uncomfortable about improvisation and clung instead to the few rules they knew.

I would like to suggest that if my own less-than-enthusiastic interpretation is correct, the poor showing of the participants can be accounted for even in those situations where music instruction is in the hands of specialists. Such persons are spread very thin in our schools. This means that the few precious minutes per week that they spend in a given class tend to be devoted to "the basics" such as singing and listening which can be taught easily en masse. Finally, the profession as a whole knows little about teaching improvisation to talented individuals, much less to large general groups.

As noted earlier the popular press had a field day when the findings from the "Performing from Notation" section were released. The sight-singing exercises, of which the example reproduced in Figure 1 is one of the simplest, ranged from very easy to comparatively difficult. The test makers reported that "few individuals were able to complete the exercise successfully and no group attained a percentage of success higher than 12%."

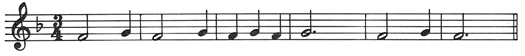

FIGURE 1. Sight-reading exercises ranged from the very simple to the relatively difficult. Exercise 1J represents one of the easier exercises. Individuals could begin on any tone they wished, singing numbers, letters, or la, la, la.

Again the panel found itself sharply divided on the subject at hand. William English asserted that music reading is an important skill, since it could lead to more advanced music making such as part singing. Dick Graham took the opposite tack that in our day and age the ability to read notation is not essential in listening to or producing music, rock performers being a good example of successful musical illiterates.

Unwittingly, the views of English and Graham, respectively, dramatized the philosophic gulf which divides the profession. One hundred and thirty years ago music was admitted to the public school curriculum as a subject almost exclusively centered around the development of skill in music reading. It remained so until the advent of Progressive Education, when it was observed that in many places vocal music had degenerated into a dry-as-dust note-reading regimen which produced as many music haters as music lovers. The enriched, multi-activity approach of the progressives has in our time evolved into one that seeks to synthesize the aims of both conceptual and aesthetic education. This philosophy of music education, which is fundamentally idealistic, must compete with both the older reading-centered curriculum and the newest one which would be based upon the lowest common denominator of popular culture.9

Only time will tell which of these philosophies will become the dominant one. Meanwhile, Paul Lehman did everyone a service when he pointed out that in the final analysis a certain minimum amount of time must be devoted to the development of a skill, if it is to be realized successfully, and that with less than minimum time available, as is so often the case with music reading in the general music class, the time is simply wasted.

That the time spent on music reading instruction has been inadequate in the public schools is a conclusion suggested by the results of various subtests in the section devoted to Musical Notation and Terminology. Barely 50% of those tested succeeded in identifying similar and dissimilar phrases in melodic structures, while somewhat fewer succeeded in spotting rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic changes in phrases which were repeated.

The ability to deal with musical abstractions such as these was undoubtedly related to success in vocal or instrumental performance, though the nature of the relationship was only glimpsed in that part of the test which dealt with "Performing a Prepared Piece." Individuals were questioned whether they presently played an instrument, what instruments they may have played in the past, and how long they had played them. They were then asked to perform two pieces on the instrument of their choice. The first was a piece which they themselves had chosen and prepared prior to the examination and the second was a piece chosen by the examiners for the purpose of measuring sight-reading ability. Seventeen-year-olds and adults who professed to be singers were asked to classify their voices as to type. They also sang two pieces, one a selection of their own choice, the other a selection chosen by the examiners for sight-reading.

Some idea of what the examiners experienced in this time-consuming and often trying process can be gained from listening to the sample performances recorded on the cassette. They include a young baritone crooning "Love Me Tender" in the best Bing Crosby style, a beginning flute-o-phone player rendering "Jingle Bells" as a pitchless rhythm pattern, a teen-age girl getting hopelessly off track in the Beatles' "Yesterday," a presumably older pianist doing a creditable amateur's job with Rachmaninoff's "Prelude in C Sharp Minor," and one of the finest folk harmonica players I have ever heard playing an unnamed country blues.

The data obtained from this section of the test was rich in human interest. Twenty-five percent of the 9-year-olds, thirty-five percent of the 13-year-olds, twenty-five percent of the 17-year-olds, and fifteen percent of the adults stated that they played an instrument of some type. The most popular proved to be the keyboard instruments with the band and orchestral instruments as serious competitors. Many respondents played various folk instruments such as the guitar, ukulele, banjo, mandolin, concertina, autoharp, Jew's harp, zither, harmonica, dulcimer, sweet potato, and ocarina.10 A number of individuals stated that they played more than one instrument.

How well they played these instruments was the subject of careful investigation. Almost all of the 9-year-olds, three-quarters of the 13-year-olds, and about half of the 17-year-olds chose easy pieces to perform for the examiners. Those giving acceptable performances rose, respectively, from fifty, to seventy-five, to eighty percent by age category. Adults, like the 13-year olds, tended to choose easy pieces and seventy percent of them performed their selections acceptably. Overall almost two-thirds of those who played an instrument gave acceptable performances. This statistic must be compared invidiously with the one obtained in the vocal area. Fewer than one half of the vocalists managed to give acceptable performances.

The panel found these results extremely disappointing, if only because performance is the one activity in which the time of music specialists is heavily invested. They noted that our schools chiefly train group performers rather than soloists. At the same time they observed that private instruction in the United States is not nearly so well developed as it is in Europe and the Soviet Union. Charles Hoffer commented that the root of the problem may well be the tendency of the average American to dabble in many areas, avoiding thereby any deep commitment to excellence, or to any one of them.

This assertion is, of course, not true of the un-average American who becomes a stellar performer. One has only to attend one of the combined concerts for band, chorus, and orchestra given by MENC at its biennial divisional conventions to know that some very fine young performers are being produced today. One wonders, however, if we aren't asking a little too much, when we expect every person who studies an instrument to stick with it until he reaches an advanced level. There are too many variables involved, including the talent of the student and the quality of the teacher. Perhaps, what we are really witnessing here are the consequences of a society that does not choose to pass judgment upon the qualifications of private music teachers, even though it does so regularly in regard to doctors, lawyers, public school teachers, and civil servants.

The test makers next turned to the American as a listener. In the section devoted to Instrumental and Vocal Media they sought to determine his familiarity with the physical appearance and the sounds of the instruments as well as the sounds of the four voice types. An estimate of his ability to identify the instruments by sight was obtained by asking him to circle certain groups on a seating plan of the Philadelphia Orchestra. About 80% of the upper three age levels were successful in spotting the trumpets. This figure dropped to 40% where the cellos and bassoons were concerned.

His ability to identify the sound of the instruments was determined by playing recordings of a number of instrumental solos in orchestral contexts. Respondents were very successful in identifying the sound of the trumpet, less so with the violin and cello together.

The identification of voice types proved to be a more difficult assignment. Less than half of the older groups could identify the alto, tenor, and bass voices, but three-quarters of them could identify the soprano voice.

The importance of these skills was a matter of some contention between various members of the panel. Charles Hoffer felt that the ability to follow two contrapuntal lines—a skill not tested by the NAM battery—was far more valuable than the ability to identify the sound of the oboe. William English retorted, "A child who knows what [the sound of] an oboe is, will be more likely to listen to an oboe concerto than one who does not know." Paul Lehman reminded the group that labels are useful tools for communicating our perceptions about music to one another. Everyone felt that many public school music teachers spent too much time on visual recognition at the expense of conceptual development because the former is far easier to teach than the latter.

In the area of Music History and Literature we come to that section of the test which will be of considerable interest to college music professors. The test makers began by asking the older respondents to put the style periods of Western music in chronological order as a paper and pencil exercise. The results which are given in Exhibit 16 show that approximately 60% understood the time relationship which exists between the Renaissance, the Baroque, the Classical, the Romantic, and the Modern.

EXHIBIT 16. Percentages of success for Exercise 4A, "Periods in Order."

This is a surprisingly good showing when one considers it is representative of a random sample. Nonetheless, the panel, with one dissenter, took strong exception to this exercise. They felt that experience with the music of different periods was far more important than the ability to rattle off their names. William English disagreed on the ground that "knowing style periods might provide a broader road to musical experience." No one could account for the relatively high percentage of success, since it is a common impression among music education professors that teachers in the public schools don't stress the periods very much these days. They are evidently misinformed about this matter.

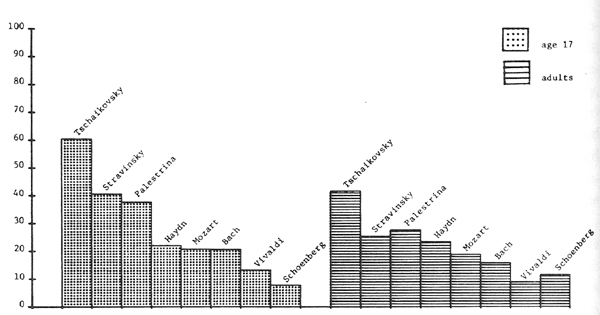

In retrospect it is clear that the panel had read too much into that which had been a very simple item designed to lead the respondent immediately into a more profound testing of his sensitivity to "Musical Genres and Styles." Here he was asked to supply the proper style period label for eight different recorded excerpts on the basis of aural perception of their essential qualities. The outcomes of this exercise are reported in Exhibit 17, which is misleading in that respondents were not asked to give the composers' names, even though the results are so labeled on the graph.

EXHIBIT 17. Percentages of success for Exercise 4B, "Choosing Style."

The test items were, with one exception, very well chosen. In the order of their appearance in the test sequence they were:

Bach. Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F Major.

Tchaikovsky. Symphony No. 5 in E Minor.

Mozart. Horn Concerto No. 4 in E Flat Major.

Haydn. String Quartet in G Major.

Stravinsky. Le Sacre du Printemps.

Vivaldi. Concerto Grosso, "L'estro armonico."

Palestrina. "Sanctus" from Missa aeterna Christi munera.

Schoenberg. String Quartet No. 2 in F Sharp Minor.

Only the excerpt from the Schoenberg Quartet was ambiguous as to period, since it teeters on the edge of the dissolution of tonality. Whether the test makers considered it to be a Romantic or a Modern piece was not reported.

Members of the panel did not comment upon these excerpts in their own report. They were unanimous, however, that the perceptions measured are very important, since they represent the kind of stylistic awareness which can only come through active listening, rather than through perusal of a textbook. They held that persons who could successfully make such distinctions by ear alone possessed a broader acquaintance with music than those who could not.

In their report they did not make any recommendations based upon this unusual test procedure. My own recommendation would be that college professors, who teach introductory courses in music, ought to consider doing more with this sort of thing. I have employed it for some years in my classes at Queens College and have found that, if I teach for understanding and perception of stylistic differences and if I use carefully chosen stereotypical test examples, the scores of my better students are generally quite good by the end of the semester.

Purists will object that no one composer can stand for his age, and statisticians will challenge the technical reliability of a measure that is limited to so few items. Both objections are valid, but I expect to continue along these lines, since such measures provide invaluable "feedback" in regard to my effectiveness as a teacher.

The test makers were evidently untroubled by such considerations, for they took their listening test procedures several steps further. They asked themselves, "If a person can perceive broad differences in the music of different style periods, can he also detect more subtle differences in the music of two composers of different periods when the medium of performance remains the same?" The point here is that, if the medium remains the same throughout a given test sequence, the more obvious clues are eliminated.

The answer to this question may be found in Exhibits 18 and 19. Respondents were asked to determine which two out of three pieces were composed by the same man. In Exhibit 18 the piano was the medium and the excerpts were taken from:

Chopin. Etude, Op. 10, No. 7.

Bartok. Allegro Barbaro.

Chopin. Etude, Op. 25, No. 7.

EXHIBIT 18. Percentages of success for Exercise 4G, "Chopin."

In Exhibit 19 the orchestra was the medium and the excerpts were taken from:

Mozart. Symphony No. 15.

Mozart. Symphony No. 17.

Brahms. Academic Festival Overture.

Commendably, about 60% of the respondents were successful in recognizing the stylistic similarities and differences in the excerpts presented to them.

EXHIBIT 19. Percentages of success for Exercise 4H, "Mozart."

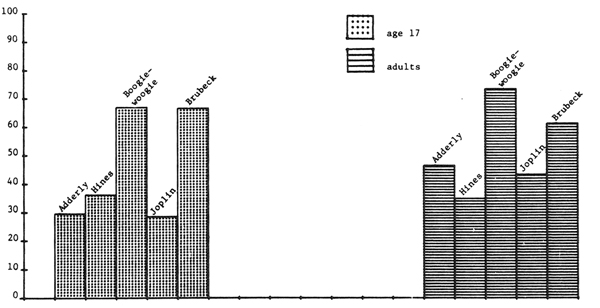

Following this tour de force the test makers, true to their philosophy of viewing subject matter as broadly as possible, repeated the stylistic experiment with four "schools" of jazz: ragtime, boogie-woogie, Chicago of the early thirties, and modern. Respondents were asked to label five excerpts by "school," even though Exhibit 20 has been labeled with the names of the composer-performers heard.

EXHIBIT 20. Percentages of success for Exercise 4K, "Jazz Styles."

Their apparent order of appearance in the test sequence was:

Brubeck. Unisphere.

Hines. My Monday Date.

Dapogny. Improvised boogie-woogie, untitled.

Joplin. Maple Leaf Rag.

Cannonball Adderly Quintet. You Got It.

Again, success varied with the style and between 60% and 70% of the respondents were able to identify the boogie-woogie and the Brubeck styles correctly. The fact that they were less successful with some of the others can readily be explained.

Jazz, in this age of rock and soul, has become an esoteric art form. Like chamber music and the art song, it has its own stars, its own audience. Jazz performers tend to be exponents of one style only, their own. The general public is somewhat on the periphery, and opportunities to hear and study the several varieties of jazz are more limited than we realize.

The findings resulting from the test makers' inquiry into music literature tend to be pedestrian, and for this reason I will pass over them quickly. Respondents were quite successful in identifying by ear the melodies of "This Land Is Your Land" and "When the Saints Go Marching In." Their lack of success with another national song, "America, the Beautiful," may have stemmed from the confusion that exists in the minds of many between it and the song which begins, "My Country 'tis of Thee."

In marked contrast are the findings presented in Exhibit 22.

EXHIBIT 22. Percentages of success for Exercise 4O, "Familiar Classics."

| Age Level | |||

| 13 | 17 | Adult | |

| Symphony No. 5, Beethoven | 19.8% | 29.5% | 15.6% |

| Grand Canyon Suite, Grofé | 3.1 | 4.2 | 14.5 |

| "Hallelujah Chorus," Handel | 4.8 | 17.7 | 38.6 |

| Nutcracker Suite, Tschaikovsky | 24.2 | 24.9 | 23.3 |

They demonstrate the fact that the ability to identify excerpts from works in the classical repertory by ear is not highly developed among the general population. This result is at odds with the fact that the works listed were drawn from the most active part of the repertory, in terms of both public performances and recorded editions.

This paradox was not resolved by the outcomes of a written exercise in which respondents were asked to match composers with their works. The findings tabulated in Exhibit 23 suggest that most Americans either do not place a high priority on such information or have been so little exposed to the works under consideration as to make recall problematical.

EXHIBIT 23. Percentages of success for Exercise 4P, "Match Composer and Work."

| Age Level | |||

| 13 | 17 | Adult | |

| Aida, Verdi | 4.8% | 6.4% | 14.7% |

| The Blue Danube, Strauss | 8.6 | 18.8 | 30.1 |

| "Toreador's Song," Bizet | 9.9 | 6.0 | 9.6 |

| Grand Canyon Suite, Grofé | 8.9 | 5.3 | 8.6 |

| Messiah, Handel | 12.0 | 23.3 | 34.9 |

| New World Symphony, Dvorak | 5.6 | 4.5 | 8.7 |

| Nutcracker Suite, Tschaikovsky | 20.7 | 33.7 | 29.0 |

| Peer Gynt Suite, Grieg | 6.5 | 6.4 | 9.2 |

| Peter and the Wolf, Prokofiev | 3.6 | 3.9 | 6.3 |

| The Rite of Spring, Stravinsky | 4.4 | 4.7 | 7.9 |

| "Stars and Stripes Forever," Sousa | 26.3 | 44.7 | 52.5 |

| Unfinished Symphony, Schubert | 9.7 | 13.1 | 13.9 |

| William Tell Overture, Rossini | 5.5 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

Members of the panel noted that knowledge about specific pieces tends to be dependent upon changing fashions in music teaching. Those of us who have been active in public school music for some time can remember when Til Eulenspiegel, Danse Macabre, and The Sorcerer's Apprentice were the listening staples of the general music class in the junior high school. None of them appears on the list. Paul Lehman summed up the feelings of the panel when he stated, "Individually these exercises are of no importance whatsoever, but collectively they show a level of musical literacy and an acquaintance with musical materials that we would like to cultivate."

Acquaintanceship with music comes about in many ways. Public school music teachers are not the sole agents for the propagation of music. Indeed, when the promotion of music for commercial purposes is considered, their efforts seem downright puny. The "A and R" men in the record companies, the disc-jockeys at the rock-radio stations, and the producers of young people's programs on television are all music educators in their respective ways. By the time they have done their jobs, young Americans have a difficult time avoiding involvement with music. Inevitably, they develop preference, if not taste; they begin to have attitudes which can have a profound effect upon their future relationship to music.

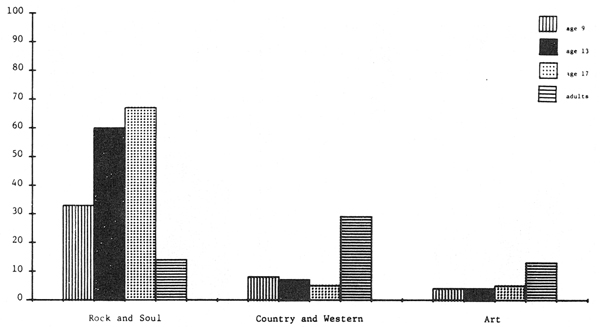

The test makers approached the measurement of Attitudes toward Music gingerly because feelings can be easily faked or exaggerated. They began by innocently asking if there was any kind of music to which the respondents enjoyed listening. Ninety-five percent answered "Yes" and went on to a question in which they were asked to indicate the type of music they liked best.

Their responses, as reported in Exhibit 24, were largely what one would expect.

EXHIBIT 24. Exercise 5E, "Types of Music Individuals Most Like to Listen To."

(Other categories, reported in the statistical report, have smaller percentages.)

The vast majority preferred popular music defined either as rock and soul or as country and western. This preference may be explained by several factors such as the generation gap, social class and regional differences, and ethnicity. Art music, which included symphonic music and opera, ran a very poor third. The fact that the figures for the three areas do not add up to 100% may be explained by the fact that other choices drained percentage points away from them. One would have thought that musical comedy and jazz, to say nothing of the music of Lawrence Welk, would have registered enough points for inclusion on the graph, but they did not, their respective percentages being lower than those of the principal categories.

These findings were illuminated by the discovery that far more people in this country listen to music on television, radio, records, and tapes than those who attend concerts, the ratio between listeners to "canned" music and listeners to "live" music being 80 to 20. This fact does not mean that our concert life is in danger of becoming extinct. Rather, it means that opportunities to attend live concerts of any kind are few and far between for most Americans, even when the ability to pay is not a factor. As has been observed before, it's a big country out there, and many people who reside in the small towns and on the farms are too isolated to take advantage of the concert life of the big cities.11

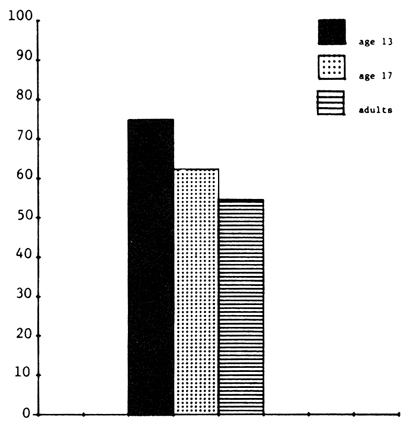

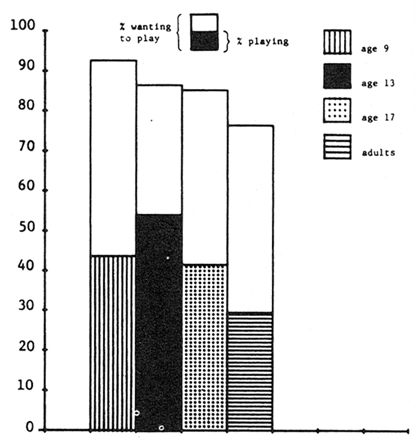

The last two graphs bear out the suspicion that lack of opportunity may well be at the root of many of the problems revealed by the Assessment. Although, as stated earlier, the development of the ability to sing has a high priority for music education, Exhibit 29 suggests that no more than 50% of our citizens enjoy singing.

EXHIBIT 29. "Individuals Who Like to Sing" (Exercise 5F).

Another exhibit, not reproduced herewith, demonstrates the fact that of those who do, less than half belong to a singing group. When the age categories associated with this statistic are examined, one is led to conclude that it is the schools and the churches which provide such opportunities as exist. Adults, apparently, have few organizations to which they can turn.

The instrumental situation is even more curious. According to the findings reported in Exhibit 31 the vast majority want to play an instrument, but less than half report doing so.

EXHIBIT 31. "Individuals Who Play Instruments or Would Like to Learn to Play" (Exercise 5G).

Evidently there are great unmet needs both in vocal and instrumental music throughout the nation. Why this should be so in spite of our best efforts is a subject to which I will return in a moment. I would like the members of the panel to have the last word here.

They rose to the occasion by recalling that determination of aesthetic sensitivity was the fundamental objective of the Assessment. They noted that measurements of attitude alone, however favorable, are not an adequate substitute for measures of a respondent's awareness of musical resources, his willingness to be exposed to new music, his judgment as to the value of music, and his commitment to music itself. Paul Lehman stated that the positive attitudes reported were in some ways superficial: almost all individuals were willing to "mess around" with music; few were willing to make a commitment to it. Charles Hoffer pointed out that messing around isn't necessarily a bad thing, that in a positive sense it is a form of exploring which could in time lead to commitment. He criticized the public schools for clinging to curricula and scheduling patterns which worked against this desire to explore, music being offered on an all or nothing at all basis in most secondary schools.

Hoffer's remarks are valuable because they raise an all-important issue regarding the availability of music in our schools. The purely quantitative situation must and does have an enormous effect upon the qualitative result.

A research team from the National Education Association addressed itself to precisely this situation in 1963. Its findings concerning the status of music and art in the public schools a decade prior to the advent of NAEP are indispensable to the attempt to place the NAM outcomes in a larger context. Neither the panel nor those involved in the latter project seem to have realized what a perfect "fit" there is between these two studies, and I would like to bring my discussion to a close by summarizing the findings of one to justify the findings of the other.

In the NEA study12 a random, stratified sample was drawn from master lists of public elementary and secondary schools in the United States. An extensive questionnaire dealing with the status of music and art was then developed and mailed to 790 elementary schools and 948 secondary schools. The results, while depressing to those who care about the place of these subjects in public education, are illuminating.

Twenty percent of the elementary schools located in small school districts and eleven percent located in large school districts did not reply. The researchers concluded, but did not verify, that such schools either had no music programs or possessed programs which would not stand up under scrutiny.

In those schools which had music programs, 97% reported that time was allotted for formal or informal instruction in music. The most typical allotment was 60 minutes a week, or 12 minutes a day, which compares unfavorably with MENC's recommendation that grades 1-3 receive 100 minutes a week, or 20 minutes a day, and that grades 4-6 receive 125 minutes a week, or 25 minutes a day.

Adequate time for instruction is one thing; the professional qualifications of those who teach music is another. When asked "Who teaches music in your school?" principals in 23% of the schools reported that it was taught exclusively by specialists, that is, by persons holding degrees and certificates in music. This figure applied to the upper grades only; it was smaller where the lower grades were concerned. Officials in 38% of the schools replied that music was taught by a combination of specialists and classroom teachers, otherwise known as teachers of common-branch subjects. Administrators in 30% of the schools noted that it was taught exclusively by classroom teachers.

There are two "sleepers" in these figures. In the specialist-plus-classroom-teacher situation, the specialist ordinarily serves as a combination music teacher and music supervisor. Supervisory ratios of 1 supervisor to 30 classroom teachers are not uncommon and ratios as unfavorable as 1 to 125 are not unknown. When the fact that those supervised, or teaching with little or no supervision, are often musically illiterate is considered, the magnitude of the problem becomes clear.13 Indeed, it is downright tragic, because, as experience has shown, the child of elementary school age profits extraordinarily from music instruction of the right sort.

How has this situation come about? To begin with, in 1963 only 20% of the states included music in the certificates of common-branch teachers. About 30% of the school systems had formal requirements, irrespective of state policy in the matter, that the common-branch teachers, whom they hired, had to be able to teach music at an acceptable level. It is a moot question how well such requirements have been enforced in the past, when qualified classroom teachers were in short supply.

If educational policy is short-sighted where vocal music is concerned, it is at least realistic when it comes to instrumental music. Instruction in this area is customarily handled by specially qualified music teachers; thus our next question is, "To what extent are programs in instrumental music available to children enrolled in the public elementary schools of our country?" Depending upon the size, and thus the affluence, of the district, between 21% and 37% offered no instruction on instruments. Of those that did, between 83% and 86% offered instruction on band instruments; between 36% and 80% offered instruction on the stringed instruments as well.

The situation in regard to facilities and equipment in the elementary schools is even more discouraging. In small districts 30% of the schools did not even own sets of the graded music textbooks, otherwise known as the standard song series. In large districts 10% did not. Pianos and record players were generally available, but the availability of other equipment such as record library, tape recorders, and auto-harps was highly variable. Lastly, only 25% of the schools in small districts and 38% of the schools in large districts owned band and orchestral instruments that could be loaned to the children. So much for equal opportunity in the elementary school!

Opportunity for diverse kinds of music study in the secondary schools is also a sometime thing. Forty percent of the smaller secondary schools and eighteen percent of the larger did not reply to the NEA questionnaire. Again the assumption was that they either had no music programs or possessed programs which their administrators did not care to discuss.

Ninety-four percent of the secondary schools which did reply reported that they offered music both as a subject and as an activity. Enrollments, as percentages of the student body, tended to be higher in the junior high schools than in the senior high schools, because music is more often required through the eighth grade, if it is required at all, than in the ninth through the twelfth grade, where it usually is an elective. In junior highs the enrollment figure was about 50%. In the senior highs it varied inversely with the size of the school, from 45% for the smaller schools to 23% for the larger ones. These percentages must be compared with the impressive enrollment figures associated with required subjects like English and mathematics when it comes to relative attainments in a national assessment.

There is more here than meets the eye. Subsequent questions in the NEA questionnaire revealed that music as an activity far outshone music as an academic subject in both the junior and the senior high school. For example, depending upon the size of the school between 68% and 92% of the senior high schools offered the band as an activity, while only 11% to 47% offered music appreciation as a course. The figures for theory were smaller still. The only consolation is that music in the secondary school is almost invariably entrusted to specialists who were rated by their supervising principals as highly qualified.

Without going into the hundreds of other statistics reported in the NEA study, we may conclude that music in the secondary school is basically an activity, and that the formal education of most Americans in music goes no further than that which prevails in the junior high school. Is it any wonder then that the participants in the National Assessment did not do as well as we might have hoped?

CONCLUSION

I cannot leave the discussion at this point, since to do so would be to do a grave disservice to those dedicated professionals who have devoted their lives to advancing the cause of music in the public schools. To a large extent the resultant programs have been a function of their leadership and of the public's own priorities in regard to education. They have repeatedly stressed the many contributions that music can and does make to the lives of individuals, to the morale of schools, and to the quality of life in communities. To an extent, the generalists who control the schools have listened to them and have supported their efforts. Nonetheless, when budgetary crises develop, music instruction is again seen as an expendable frill.

This attitude is potentially the most dangerous one we face. In many places, especially in our larger cities,14 music programs, like those in art and physical education, are in retreat. As the problem of financing public education grows ever more serious, there is a real possibility that those in positions of power, the men who have never been moved by "the concord of sweet sounds," will use the Assessment results as an argument for further emasculating, or even eliminating, music on the ground that music programs are ineffectual—research proves that this is so!

Such specious reasoning cannot be permitted to stand unchallenged. We must argue the true meaning of the NAEP and NEA studies: music education hasn't so much been tried and found wanting, as it hasn't been tried at all in some places and but imperfectly implemented in others. We must point out that there are many fine programs in the United States and that the evidence from them, which has been swallowed up by the statistical procedures of the studies, suggests that comparable programs ought to be established throughout the country until equal opportunity in music is a reality for all our citizens.

At the same time we should not delude ourselves or our auditors. The musical attainments measured by the test makers are but manifestations of musical achievement. This educational outcome in turn is a function of musical aptitude and general intelligence, two human traits which are normally distributed among the population. Thus, even if equal opportunity can be achieved, we must be ready to accept gracefully a rather mixed result. For, as Jacques Barzun has said:

The fact remains that art is something for the few, and who those few are is unpredictable. They are not superior for being the few, and no proof exists that they are happier.15

He has further held that in a democracy we must expect and should learn to tolerate an easy-going art alongside an art which is intended for connoisseurs.

Barzun is correct when he asserts that we cannot know in advance who will decide to enrich his life through a continuing involvement with art, regardless whether it be through music, literature, painting, or the dance. The function of general education in the arts is to prepare each individual to decide for himself, not on the basis of peer-group pressure or commercial pandering, but on the basis of informed, skillful acquaintanceship which fields, if any, he will embrace as his own. If we as music educators, and here I include everyone from the kindergarten teacher introducing her charges to the nursery song "Eency, Weency Spider" to the college professor introducing his charges to the ballet Le Sacre du Printemps, fulfill our respective missions, there need not be much concern about the musical attainments of the American people.

1National Assessment of Educational Progress, Suite 300, 1860 Lincoln Street, Denver, Colorado 80203.

2Official National Assessment Reports in Music (1971-72 Assessment):

03-MU-01 The First National Assessment of Musical Performance $0.55 03-MU-02 A Perspective on the First Music Assessment .45 03-MU-03 An Assessment of Attitudes Toward Music .85 03-MU-00 The First Music Assessment: an Overview .60 03-MU-20 Music Technical Report: Exercise Volume 10.10 03-MU-21 Music Technical Report: Summary Volume 2.10

N.B. National Assessment reports should be ordered directly from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402.

3See A Perspective in Note 2.

4Richard Colwell, Music Achievement Tests 1-4.

5Edwin Gordon, Iowa Tests of Musical Literacy.

6The present monograph has been based in part upon the Overview and the Perspective volumes listed above. Acknowledgment properly ought to be made to Frank W. Rivas of the NAEP staff who wrote both of these reports with objectivity and clarity.

7The exhibits reproduced herewith have been taken from the Overview by permission of NAEP. Their original numbers have been retained so that their relationship to the other exhibits in that volume will be clear.

8To supplement the printed reports the National Assessment has produced a 60-minute cassette explaining the scoring criteria for the performance exercises and presenting the musical stimuli used in the nonperformance exercises. The cassette may be purchased for $2.00 from NAEP at the address listed above.

9See "Youth Music—A Special Report" in the November 1969 issue of the Music Educators Journal, particularly the articles "Give Bach a Sabbatical" by Allen Hughes and "Roll Over, Beethoven" by Thomas MacCluskey.

10The lute and the recorder were also included in this list, though many would object to their being designated as folk instruments.

11A notable exception is to be found in North Carolina, where a state-supported symphony orchestra of professional calibre regularly performs works from the standard repertory throughout the state.

12Music and Art in the Public Schools (Research Monograph 1963-M3) published by the National Education Association.

13See Vincent J. Picerno's study of music education in New York State, "The Role of the Elementary Classroom Teacher and the Music Specialist: Opinions of the Music Supervisor," published in the Journal of Research in Music Education, Vol. XVIII, No. 2 (Summer 1970), pp. 99-111.

14New York City has reportedly fired over 1,000 music teachers out of a force of 3,000 who were employed in its public schools. Music programs in the elementary schools, which never were thoroughly developed because of the Board of Education's refusal to license special music teachers at that level, have been grievously hurt. The situation at the secondary level, where music specialists have always been licensed, is not much better, since music faculty has been progressively reduced in many schools, the younger instructors being "excessed" first.

15Jacques Barzun, "The Arts, the Snobs, and the Democrat," Aesthetics Today, edited by Morris Philipson (Meridian Books, 1961), p. 20.