In these days of shrinking student enrollment and possibly diminishing monetary support for the fine arts in the community, it would seem an appropriate time to re-assess our attitudes toward the function of music within a school environment as well as society as a whole. At a time when the sound of music (Muzak) seems to be everywhere, this art form might be considered to be a constant part of daily life.1 Yet a systematic attempt to understand the principles and practices of music in detail is only presently available through some sort of instruction—in schools for the most part although to lesser extents in the churches or through private study. While the latter are beyond the scope of this paper, some consideration of the first mechanism is pertinent.

By far the largest number of people encounter music instruction through "appreciation" courses designed to present a historical style continuum through a combination of listening and textbook study. A smaller group participates in performing ensembles. These latter students often gain great levels of technical expertise due to ensemble study of specific compositions. Just as often these same students have little "appreciation" of the style continuum because it is inconvenient to teach history in the rehearsal or the instructor, for one reason or another, cannot do so. Shall never the twain meet?

One answer is to continue the "appreciation" courses much as they are and increase the level of "appreciation" within the ensemble. In this regard there is merit in examining the close analogy between music and physical education within the school situation. Team sports and performing ensembles serve as an intensive experience within the context of a general program, i.e., everyone receives a general introduction to physical education in the hope that each person will develop and be interested in maintaining a certain level of physical fitness during the remainder of his lifetime; a similar philosophy underlies the music "appreciation" courses. Only a smaller number of people choose to participate in team sports or music ensembles, generally because of a real or perceived necessary minimum level of expertise. Both team sports and ensemble music-making place a substantial number of individuals with initially dissimilar skill levels into a situation wherein they depend for ultimate success upon striving together (teamwork). Both focus upon a common goal of public display (game or concert). Both rely upon a skilled, specialized instructor to guide their progress.

There have been enormous scientific and technological changes in the training methods for team sports over the past two decades. No self-respecting training program would be complete, or competitive, without some form of individualized weight and strength training for each participating athlete. Such training helps to develop the stamina and endurance necessary for peak performance. Similarly, each player receives small group instruction according to his area of specialization (line coach, pitching coach, etc.). Teams gather together to study their own and their opponents' past performances. Under the coaches' supervision (slow motion films, etc.) this can be quite helpful in determining past mistakes, discovering weaknesses, and pinpointing successes. Finally, there are "skull sessions" for players to study playbooks, game plans, etc., to determine their own responsibilities within the entire framework of the program.

All of these training steps take time, time which is either scheduled into a student's classroom day or expected extra-curricularly. Athletic training generally takes place during the late afternoon hours, and often the last period of the school day is assigned to athletes as a physical education class so that there is an overlap from the normal school day into the free hours of the late afternoon. Athletes are expected to stay in shape during the off season, often in a very structured program of daily weight training and running. In sum, the student athlete undergoes a sophisticated regimen which is designed to maximize individual and therefore team results.

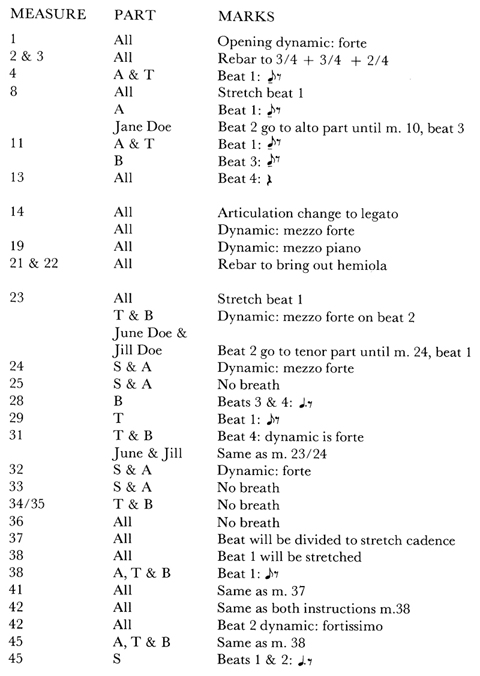

If there is a parallel between ensemble music and team sports, can we extend the parallel to training methods? In place of individualized weight and strength training let us substitute musical exercises for endurance and stamina, i.e., breathing exercises and technical warm-ups. For specialized group instruction let us substitute sectional rehearsals including ear training. Instead of watching films of games, ensembles can review audio and video tapes of their own past performances as well as recordings made by other ensembles. Finally, during "skull sessions" performers can study the score under the guidance of the director. Included here would be non-performing pencil sessions devoted to marking breathing, dynamics, phrasing, and divisi into the score. Depending upon the sophistication of the ensemble members this can be done by the individual at home according to hand-out guidelines (see Example 1) or as a group.

EXAMPLE. 1. CANTATE DOMINO—HASSLER

The advantages of dividing a rehearsal schedule into such component blocks are significant, and increase the opportunity to inject "appreciation" material into the preparatory process. Unfortunately, few musical ensembles have similar amounts of practice time as athletic units. There are important reasons for this, among them a heavy societal emphasis in North America upon sports. A discussion of this subject is, however, beyond the scope of this article.

To continue the comparison, a successful team sport program requires money for sophisticated equipment, specialized coaching, travel expenses, etc. If a musical ensemble is to adopt the new training methods outlined above there are similar financial needs. On the other side of the coin, athletic events bring in gate receipts. Athletic directors are quite right in pointing out that a certain portion of expenses (varying from school to school and, more significantly, from sport to sport) is covered by ticket sales. Concurrently, coaches are seemingly always courting alumni or civic boosters in an attempt to entice giving for the support of an athletic program. Should there not be a parallel effort in music fund raising?

Team sports are said to build character through teamwork, including the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat. Musical ensembles also build character through teamwork, and the thrill of performing something right, and the agony of having something go wrong at the last moment even after hours of rehearsal. Team sports build tolerance and co-operation of individuals for the greater benefit of the group. Again a parallel applies in music. Team sports teach individuals about life by showing that through hard work and concentrated effort one can succeed. Once more musical ensembles provide the same opportunity.

By now it should be evident that musical ensembles bear more than a passing resemblance to athletic teams in their purposes and benefits. It is in the director's best interest to convince the general public of the validity of the comparison. Just as importantly, the potential participating population needs to discover the benefits of ensemble music making, for the best training facilities in the world do no good if they are not used. Consequently, the director needs to approach the public relations aspect of his position with considerable care and effort. Primary areas of concern are recruiting new members and building community interest in all facets of the program.

A first step is to organize a professional-looking training program which will appeal to administration and students alike. Such a program might look like the one shown in Example 2.

EXAMPLE 2. FALL 1978 SEASON

| WEEK | 1 | ||

| 2 | Intra-ensemble performances September 13 and 14 Alumni performance September 15 at Elks Lodge |

||

| 3 | September 21 at Rotary (10 min.) | ||

| 4 | September 27 at Extendicare (12 min.) | ||

| 5 | October 4 at Senior Citizens Center (12 min.) | ||

| 6 | October 11 at Drop in Center (10 min.) | ||

| 7 | October 18 at St. Paul's Women's Club (20 min.) | ||

| 8 | October 25 at Knights of Columbus (25 min.) | ||

| 9 | November 1 at Lakeview Elementary (20 min.) | ||

| 10 | November 8 at Holy Cross WA (30 min.) | ||

| 11 | November 15 at Martin H.S. (30 min.) | ||

| 12 | November 22 at Balfour H.S. (25 min.) | ||

| 13 | November 29 at LeBoldus H.S. (30 min.) | ||

| 14 | December 6 at Central H.S. Open Dress Rehearsal | ||

| 15 | December 13 at Recital Hall, Evening Concert |

A fifteen-week "season" was chosen for a number of reasons. With or without one or two weeks before the start of school in the fall, this could encompass a fall-to-Christmas schedule. For the generally longer spring term in a public school situation (or the ten-week college term) the process could be altered accordingly. Other considerations should include whether you are performing at a major league, minor league, little league, or other level, and whether you are in season, or in off-season.

Basically the schedule can be broken down into four components parts. During "training camp" (weeks 1 and 2) the most important things are to learn fundamentals of performance and to master the playbook. Here the "veterans" of the squad can perform a great service by working with the "rookies" in such areas as mastering the exercises and notational complexities. No training camp would be complete without an intrasquad game or two, and in fact dividing your ensemble into two or more smaller groups would allow the non-performers to assess good and bad aspects of performers. Often the athletic training camp ends with a varsity vs. alumni game. If the "training camp" literature were to include some selections from previous years' repertoire, perhaps local alumni would welcome the opportunity to participate in a first public exhibition. Possibilities for this might be performing one or two numbers for a local church service, rest home, or service club.

Exhibition games (weeks 3 to 6) serve to discover the best performers at any particular position—the "first team." They also help to establish a winning attitude and provide an opportunity for showing how the individuals work together as a unit. For performing ensembles this is a time to divide into groups of similar strength and adequate balance. In other words, if at your training camp you have combined every singer or player in your total program, now is the time to assign each person to a permanent "team" where he will derive the most benefit. The idea of a "farm system" is, of course, not new, but the possibilities are staggering.

During the regular season (weeks 7 to 13), teams give periodic public displays of their abilities to prove to their customers that they are providing valid entertainment as well as to maximize profit2 from the training investment. In this way, fan enthusiasm is built by performing well and establishing a winning record to make the play-offs or tournament. It is during this portion of our hypothetical "season" that the most modification according to individual situations will be necessary. If the same level of student commitment is evident in the ensemble as in the football team, there is no reason why one performance per week is not possible.3 These need (and probably should) not be full evening concerts unless the audience demand is present.4 The notion of regularized performance times should not be discarded out of hand. Let us suppose that every performer knew from the beginning of the "season" that in addition to daily practice there would be a performance every Wednesday evening, for instance. For how many service clubs, rest homes, and other types of meetings could you provide twenty minutes to one half hour of entertainment over the course of a "season"? Imagine the benefits of regular performances to the team in the areas of stage presence, character building, etc.

Finally, the play-off or tournament portion of the season (weeks 14 and 15) presents to your audience a complete performance, both in terms of a full evening's repertoire and by a complete team as well. If all of this seems a bit ambitious, perhaps it is. However, it is a possible step toward providing your institution with a very special commodity—public profile. On the other hand it may be a program that will require a certain level of financial support, support which will not completely be provided by the box office. One time investments in audio and video equipment, sensible scheduling, and specialized staff are a basic minimum. Consider the potential benefits to the participating ensemble member—are they not worth it?

Finally, the reader will note that although team sports are based upon competition there has been no word as to that aspect of musical ensembles. Each director will have to make his own decision about whether more or less emphasis will be placed upon competition either between groups at one institution (the "farm system") or in a formalized way between competing ensembles of differing institutions in a festival situation. Special conditions affecting his individual campus and its personalities will ultimately govern his decision.

1Witness the musical contributions in the story lines of such motion pictures as Car Wash and Saturday Night Fever, to name just two.

2Profit here is used in more than a monetary sense, although in certain instances monetary profit is all-consuming.

3The double negative is used deliberately here, for possibilities are not always realities.

4Of course church choirs must face a weekly performance schedule as part of their commitment.