Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, like so many other cities in the United States, seems to have lately come to a realization of the necessity for determining and preserving the contributions of its outstanding citizens. The unprecedented success of Stefan Lorant's popular history of Pittsburgh is ample evidence that today's residents are justifiably proud of the role their city has played in the country's development.1 This renaissance of interest has extended to the cultural legacy of a city which has long projected a blue-collar, industrial image. In terms of musical contributions, Pittsburghers are rediscovering others who, like their beloved Stephens Collins Foster, have attained considerable recognition as composers. Indeed, several of these individuals achieved national, and in some cases, international reputations. The last few years of the nineteenth century through the opening decades of the twentieth were particularly productive in this respect, with the respected names of Charles Wakefield Cadman, Ethelbert and Arthur Nevin and Adolph Foerster long familiar to those interested in American music. However, the name of another individual—one who was perhaps held in higher esteem by his contemporaries than any of the foregoing—has only very recently resurfaced.

On May 22, 1960 an article appeared in the Pittsburgh Press which announced the transfer of a unique portion of that city's musical history.2 The text alluded to a cache of original musical compositions presented to the University of Pittsburgh by the heirs of Fidelis Zitterbart Jr., a prolific American composer, conductor and performer of the late nineteenth century. The nearly fifteen hundred works of this only partially catalogued collection represent the legacy of an individual who enjoyed a healthy reputation in this lifetime. However, Zitterbart remains a virtual unknown to the present generation. His lasting contribution to American music deserves a scholarly assessment.

As the product of a musical family, Fidelis Zitterbart Jr. seemed predestined to his career. The composer, who was born in Pittsburgh on April 8, 1845, was given his first musical instruction by his father, a distinguished composer and conductor in his own right.3 At age nine, Fidelis assumed a place as violinist in the venerable Drury Theatre orchestra. This, the city's first professional orchestra, was conducted for twenty-four years by the elder Zitterbart. Until sixteen the young musician was content to study locally. Then, as were so many of the musically talented young Americans of his era, Zitterbart was sent to Europe for additional training. For two years he studied violin with François Schubert, a noted virtuoso and composer, in Dresden. Julius Ruhlmann, then one of Germany's better pianists and an individual who would later attain a considerable reputation as a musicologist, furthered Zitterbart's knowledge of theory and keyboard during the European sojourn.4

In the ten years from 1863, the year of his return from Europe, to his permanent relocation in Pittsburgh in 1873, Fidelis proved his ability as a violinist with several of the country's premier musical organizations. Capitalizing upon his father's success as a conductor, he first joined the elder Zitterbart's New York Theatre orchestra. Then for three years he toured extensively as first violinist with the Theodore Thomas orchestra, an organization which maintains a respected place in the history of nineteenth century orchestral music in the United States. Later he accepted the position of concertmaster with the Strakosch Opera orchestra. Zitterbart was also a member of the New York and the Brooklyn Philharmonic Societies, as well as the Onslow Quintette Club, during his residence in New York City.5

The prodigal's return to Pittsburgh was prompted by an offer to teach at the recently opened American Conservatory of Music. This establishment became a musical landmark in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, praised by contemporaries as being one of the finest schools of its kind in the East.6 Zitterbart founded his own school when the Conservatory closed and continued teaching until shortly before his death in 1915. In numbering among his students many of the area's finest musicians, Zitterbart assured one facet of his musical contribution to that city.

His teaching duties notwithstanding, Fidelis continued and even expanded his performing and conducting activities. He was appointed director of the Pittsburgh Philharmonic Society and its successor, the Beethoven Society. In the 1880's he organized the Zitterbart Orchestra, one of the city's better amateur musical organizations for several years. He was, in addition, a life-long member of two important musical organizations claiming a national membership: the Aschenbroedal and the Frohsinn Societies. However, any appraisal of Zitterbart's wider contribution must ultimately rest with an evaluation of this indefatigable individual's legacy of compositions. Fidelis Zitterbart Jr. the composer was, from every indication, an individualist cast in the mold so cherished by his countrymen—an attribute which has contributed to his relative obscurity. The younger Zitterbart had a chronic mistrust of publishers which seems to have stemmed from an incident occurring early in his career. In 1864 his first composition, a "Nocturne" for keyboard, was sold to a publisher who promptly went out of business, depriving the composer of the royalties which should have normally been forthcoming. As a result, the bulk of the composer's prolific output was never submitted for publication—indeed, many works were never even afforded a public performance.7

After the composer's death, the collection itself remained in the Zitterbart family until 1960 when, largely through the efforts of Professor Theodore Finney, it was entrusted to the University of Pittsburgh. The manuscripts are presently housed in the Special Collections Archives of the University's Hillman Library. Nearly fifteen hundred compositions are shelved in seventy-five undifferentiated boxes, each measuring 4 × 15 × 12 inches. Unfortunately, no usable catalogue of this extensive collection has as yet been made.8

The Zitterbart legacy reflects the wide-ranging musical interests of its composer. Even a cursory examination of the collection reveals an amazing diversity. Zitterbart seemingly wrote for every conceivable chamber combination—there are at least 125 string quartets in addition to numerous piano duos, trios, quartets, and quintets for a variety of combinations: sonatas for violin and piano and at least two series of concert etudes for piano.9 Grand opera is represented by at least one work, Ina, on a libretto by Hubert C. Tener and, on the other end of the spectrum, there are short popular compositions of every sort. Zitterbart's orchestral output ranges from dances through single movement symphonic poems and overtures, to a dozen symphonies. These works are all the more interesting in light of the fact that American composers, during Fidelis Zitterbart's lifetime, had little hope of having orchestral compositions adequately performed.

Zitterbart, perhaps inevitably, found himself embroiled in the "American music" controversy. Debate centering upon the merit of native composers vis-à-vis their European contemporaries was a popular topic in most of the nation's major cities beginning in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. During Zitterbart's active years American composers were normally perceived as suffering in such comparisons. This state of affairs quite naturally created a serious problem for native composers. The management of many American orchestras exhibited notoriously conservative programming policies. This, in turn, resulted in the dearth of home-grown works represented in the concerts of these organizations.

Pittsburgh and its newly formed orchestra, under the direction of Victor Herbert, did not escape the debate. An article which appeared in the Pittsburgh Leader on February 18, 1900 urges the orchestra management to perform the works of native American composers. In the process the several references to Zitterbart provide valuable insights into the composer's reputation during his lifetime.

Working up a Strong Sentiment

Local Musicians Begin a Campaign Against

Alleged Exclusion of American Composers

There seems to be a concerted movement upon the part of Pittsburgh symphony musicians and composers outside the personnel of the Pittsburgh symphony orchestra, to create a sentiment in favor of the works of American composers, with the end in view of forcing Director Victor Herbert to include the compositions of native composers in his weekly programs. Whether there is any real public demand for American composition for orchestra is a question the future must determine, but it is a fact beyond dispute that a campaign in that direction has been inaugurated by local musicians and their followers. The first evidence of this given to the public was a letter in last Tuesday's 'Leader', over the signature of Prof. Simeon Bissell, composer of the light opera, 'Luciella', but the writer has known for several weeks that the matter was being agitated. It has been asked why such American composers as McDowell, Chadwick, Arthur Foote, or, coming closer to home, S.M. Foerster, Charles Davis Carter, Fidelis Zitterbart, and others, are not played by Mr. Herbert's orchestra. The ones who feel aggrieved at this ignoring of what they term American genius say that during the entire two seasons that Mr. Herbert has been director of the orchestra not a single composition by native American composers, excepting a symphony by Hadley, has been rendered. Hadley's symphony no. 1 in F Major was one of the numbers in last week's program. As the feelings and sentiments of the local musicians and composers and many patrons of the orchestra, or those having the interest of musical art at heart, the following letter sent to George H. Wilson, manager of the orchestra, and each of the members of the music committee, is a good index. It was inspired, it is said, by local composers:

'George H. Wilson, Manager:

Dear Sir:

As the close of the second season of Mr. Herbert's directorship of the orchestra draws near, a question presents itself, which is voiced by a very large contingent of the concert-going element of this community. A great many members of the Art Society and a great many subscribers to the orchestra concerts wish to know why the orchestra management has felt justified in ignoring the existence of a list of superb compositions for orchestra by American composers. Here is a great orchestra in an active American city, managed by a native American, supported by American guarantors and patronized by American citizens, at whose concerts world-famous orchestral works by native American composers are tabooed.Mr. Herbert's unfortunate, though unaccountable, antipathy to American orchestral works is exciting a great deal of unfavorable comment among the patrons of the local orchestra concerts. There is a popular desire to hear a program of American orchestral works by native American composers before, or at the close of the present season. Would it not be an admirable thing to do to make the final concerts (March 9 and 10) a notable patriotic event; an occasion for a representation of American orchestral works, and invite the composers to direct their own compositions? Let our representative men as McDowell, H.W. Parker, G.W. Chadwick or others be invited to contribute each a composition to the program, and; if possible, to conduct in person. Let our representative Pittsburgh composers, A.M. Foerster, Charles Davis Carter and Fidelis Zitterbart direct, each one, an orchestral work. A closing of the season with a gala performance of great orchestral works of symphonic proportions of native American composers, works which, though well-known and appreciated for their artistic value outside of Pittsburgh, have never received a hearing in this city, would unquestionably arouse a patriotic enthusiasm in the local musical world that must augur well for the future of the orchestra and well direct the attention of Pittsburgh music lovers to the development of American art.

Within four days, orchestral works by the composers mentioned, or any others the management may choose to consider, can be in rehearsal in preparation for a notable closing concert. I trust, sir, that you will receive this communication in the spirit in which it is sent, not as desiring to criticize in any respect the past work of your committee, but that you may be induced to lend your influence to secure this most admirable result.'

George H. Wilson, manager of the orchestra, said to a 'Leader' reporter, when asked about the above: 'The arranging of the programs is not my province. I have nothing to do with it. Mr. Herbert is sole judge of what compositions shall be selected. I believe, however, that the orchestra is doing something along the lines suggested in the letter I received, for we have one of the Hadley symphonies on this week's program. This is considerable, too, for to prepare for such a work means an hour or two's rehearsal every day during the week. No one has hitherto complained to me, or as far as I know, any of the guarantors or members of the music committee, about the kind of music rendered by the orchestra.'

Mr. Herbert was seen at his home on South Negley Avenue, and manifested much impatience at the complaint in the letter. Said he: 'I have no personal feelings at all against any native composers, Pittsburghers or others, and the statement that I entertain an unaccountable antipathy to American orchestral works is not true. In selecting compositions for my programs I am actuated entirely by motives to have the best obtainable. Artistic merit must rule—no other. In the United States, there are not more than six or eight composers who have written works scored for orchestra of the best artistic quality. There are many works of fair or creditable quality, but it is the office of a symphony orchestra to give only the very best and most representative works of all schools. After you have mentioned Henry Clay Hadley, Arthur Foote, G.W. Chadwick, all of Boston, and McDowell, of New York, Arthur Nevin and Zitterbart of Pittsburgh, and two or three others, you have run the gamut of American composers of orchestral works. Other excellent composers, such as Walter Damrosch, Ethelbert Nevin, have written songs, choral, or pianoforte numbers, but have not done anything for orchestra. It will not do for a great symphony orchestra to play merely good selections, they must be artistic as well. When the Art Society founded the orchestra, it was with the distinct understanding that only the best kinds of works should be given.'

When asked how it was that American compositions were only beginning to be heard of at the close of the second year's season, Mr. Herbert explained that it was difficult to fit them in with the programs which were always of the highest excellence. America as yet has produced no works equal in originality, treatment or technique to the compositions of European masters. 'Hadley's symphony is not the first piece by native American composers that the orchestra has rendered,' he added. 'We gave Arthur Nevin's "Lorna Doone" last year, and I told Mr. Nevin the orchestra was ready to play his new suite as soon as he sent us the score. I have been intending to give some of Chadwick's and McDowell's works for some time, but as I say, it is difficult to always fit them in a highly classical program. Fidelis Zitterbart's works have been given, Mr. Zitterbart himself directing the orchestra.'

The director then said that for some time persons in this city desirous of having their compositions played by the orchestra, had by devious and round-about ways tried to influence him through friends to include such compositions in the repertoire. This Mr. Herbert could not accede to unless the works were up to an artistic standard of which he was given full power to judge. He resented the public or individuals trying to teach him how his programs should be made up. He thinks his many years of directing bands and orchestras and playing in the best organizations in the country, as also hearing the best orchestras in Europe interpreting the highest forms of musical art, should have fitted him in judging of orchestral compositions. 'Anybody that has any artistic work, no matter who he is or who he isn't, will get a hearing,' continued Mr. Herbert; 'but there is no use in anybody trying to foist works on the orchestra that do not come up to requirements. There is no pull or influence about it. It is all pure merit. I recognize art as belonging to the world—as universal—and will be only too glad to give native compositions a hearing.'10

Heated debate notwithstanding, a sampling of programs presented during the first decade of the twentieth century by major American orchestras would seem to confirm that few native composers found a forum for their compositions in the performances of this, or any similar organization. Thus, the select list of individuals whose works were programmed is worthy of note. Obviously, these composers were considered to represent the best at their craft to be produced in this country by their conservative, and often European born and trained, orchestral peers. It is to Zitterbart's credit that his compositions are praised by both sides in this article. Those who wished to hear the orchestra perform more of the credible work of Americans single him out as one whose compositions deserve a hearing. Maestro Herbert, in defending his musical choices as being governed solely by artistic and not geographic considerations, affirmed that the compositions of Zitterbart have been performed by the orchestra, and intimates that their quality is such that they would probably be programmed again. Fidelis Zitterbart found his serious compositions so honored on several occasions and by several outstanding orchestras during his lifetime.

The composer himself is said to have considered the overtures and symphonies representative of his finest efforts, a view evidently shared by others. The orchestra of Theodore Thomas programmed the overtures of its one-time violinist on various occasions.11 One such work, the overture Richard III, was awarded the first prize in a nationwide competition judged by three highly respected figures in American music—Victor Herbert, Walter Damrosch and Arthur Foote. Zitterbart's Caprice Humoresque, for piano, was awarded a first prize for keyboard compositions in the same competition. The circumstances surrounding the entry of these works provide an interesting insight into the nature of the composer. It seems that Zitterbart's son-in-law, Carl J. Braun, Jr., knowing that the composer would never consent, submitted the winning compositions without approval. It is a measure of Fidelis' unassuming character that, even after they had won the accolades of so distinguished a panel, he adamantly refused to have them published.12

In addition, the program notes for a Pittsburgh Symphony concert of February 9, 1930 cited the following performances.13 On February 12, 1909, under the direction of Emil Paur, the old Pittsburgh Orchestra played an American program in honor of the Abraham Lincoln centenary. The program included two movements of Zitterbart's symphonic poem A Sailor's Life conducted by the composer. The Pittsburgh Orchestra, under Victor Herbert, played Zitterbart's overture Richard III and the Domitian overture. The Pittsburgh Festival Orchestra, with Carl Bernthaler as its director, played Zitterbart's overture Iago and A Sailor's Life in 1909. Wassili Leps and his orchestra played a portion of the composer's Symphony in D Minor and the symphonic poem Hamlet at the Exposition in 1915. Modest Altschuler and the Russian Symphony Orchestra played the overture King John in 1916 and Sousa's band performed the overture Columbus in the same year. In addition, the same article mentioned several other works by this composer as having been performed by unspecified orchestras in both Pittsburgh and New York.14

Nor was Zitterbart's reputation strictly limited to the admiration of his contemporaries. Newspaper accounts and surviving program notes indicate that his compositions were the subject of revival on more than one occasion after his death. One of the first of the several "rediscoveries" of the compositions occurred in 1930 when the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra programmed his Macbeth overture.15 Interestingly this was the first public performance of the work, although it was composed in 1876. Antonio Modarelli, then the music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony, sparked another revival of interest in Zitterbart's works when, in 1934, he declared the composer's Symphony in D to be "one of the finest compositions known."16 That year witnessed the performance of several of his chamber works and compositions for organ by local and national artists, in addition to the Pittsburgh Symphony's inclusion of the Symphony in D in the repertoire for its 1934 season.17 Following this brief flurry of activity the composer's name and works were again submerged until 1960, when interest was spurred by the publicity resulting from the transferral of the collection to the University of Pittsburgh.18

Zitterbart's music often reflects a literary approach characteristic of a composer heavily steeped in the late Romantic style. As a result his titles frequently indicate the composer's desire to impart meanings other than purely musical. Representative examples are to be found among his most ambitious serious works as well as those written in a lighter, more popular vein. Of the latter, a work like Pittsburgh by Day and Night is illustrative. Subtitled Volksstücke-Humoristisches Tongemälde, it is a string quartet composed in 1875. Its twelve (!) movements are all provided with descriptive titles.

A significant portion of Zitterbart's large orchestral works is programmatic. Indeed, perusal of the composer's biography suggests at least one profitable source of extra musical themes. Zitterbart's long association with theatre orchestras, first as an orchestral musician and later as an arranger and conductor, undoubtably sparked a continuing interest in Shakespeare. In 1930 William R. Mitchel, then the music critic of the Pittsburgh Press, included the following remarks on the occasion of a revival of Zitterbart's symphonic poem Macbeth by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra:

As Zitterbart was a musical prodigy—any person who can play violin in a first rate orchestra at the age of nine years surely must be classed as a prodigy—it is not beyond the range of possibility that here he got the germ of the idea to put Shakespeare in tone, later on. And it would be no stretch of the imagination to state that [Edwin] Booth himself, great genius of the stage, who played Shakespeare there "many time and oft," influenced the precocious youth.

Records show that Booth—rated as the most noted Shakespearean actor America ever produced—played engagements at the Old Drury. . . . Booth appeared at this theatre in repertoire, including such plays as "Hamlet," "King Lear," and "Othello," and likely enough, in one of his favorite roles, "Macbeth." Thus, we perceive how the trend of events influenced the youthful Pittsburgher, who drank in these illustrious plays, absorbing their real beauties and significance. Thus it was, doubtless, that the overture, "Macbeth," had its inception.19

In the same vein are the overtures Iago (1892) and Richard III. The orchestral suite Faust is another obvious example of Zitterbart's dramatic interests.20

The critical questions involving the lasting value of Fidelis Zitterbart's legacy must hinge upon a thorough contemporary analysis of the music itself. Certainly quantity alone will not assure the composer a permanent place in American musical history. Neither, however, should Zitterbart's prolific output necessarily be viewed negatively. In the same vein, the accolades of the composer's peers should spur the interest of today's musicologists—although it is not difficult to discover individuals whose exalted reputation during their lifetime has become justifiably faded with the passing years. Hopefully, the improved access provided by the University of Pittsburgh's acquisition of the collection, coupled with the increasing interest in our unique American heritage, will ultimately provide valuable insights into a little researched and even less understood period in our cultural history.

1Stefan Lorant, Pittsburgh, The Story of an American City (Lenox, Mass.: Author's Edition, Inc., 1975). There have been two editions and five printings of the work from 1964 to 1975.

2Michael Holmberg, "Music Treasures Hidden Here," Pittsburgh Press, May 22, 1960, Sec. I, p. 12, cols. 1-3.

3Fidelis Zitterbart Sr. was an already established violinist when his name first appeared in Pittsburgh records two decades before the outbreak of the Civil War. Born on April 20, 1804 in Einsiedeln, Bohemia, he came to the United States as a member of the "celebrated Prague company of instrumentalists"—one of many European musical organizations that saw in this country a virtually untapped audience. The Prague company did not experience the anticipated economic success and disbanded without completing its tour in 1837. Fidelis Sr. remained in the United States and, after stays in New York City and New Orleans, settled in Pittsburgh. Contemporary sources lauded him as a composer and a teacher of violin and piano. However the elder Zitterbart was perhaps best known in circles for his abilities as a conductor. He directed Pittsburgh's Drury Theatre orchestra for twenty-four years and numbered the important New York Theatre orchestra on Broadway among his conducting assignments.

4Edward Gladstone Baynham, A History of Pittsburgh Music 1758-1958 (Pittsburgh: pub. by the author, Dec. 31, 1970), p. 148.

5"F. Zitterbart, Musician Dies," Pittsburgh Post, Aug. 31, 1915, "Newspaper References: Pittsburgh Musicians. Fidelis Zitterbart," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

6Baynham, History, pp. 384-5.

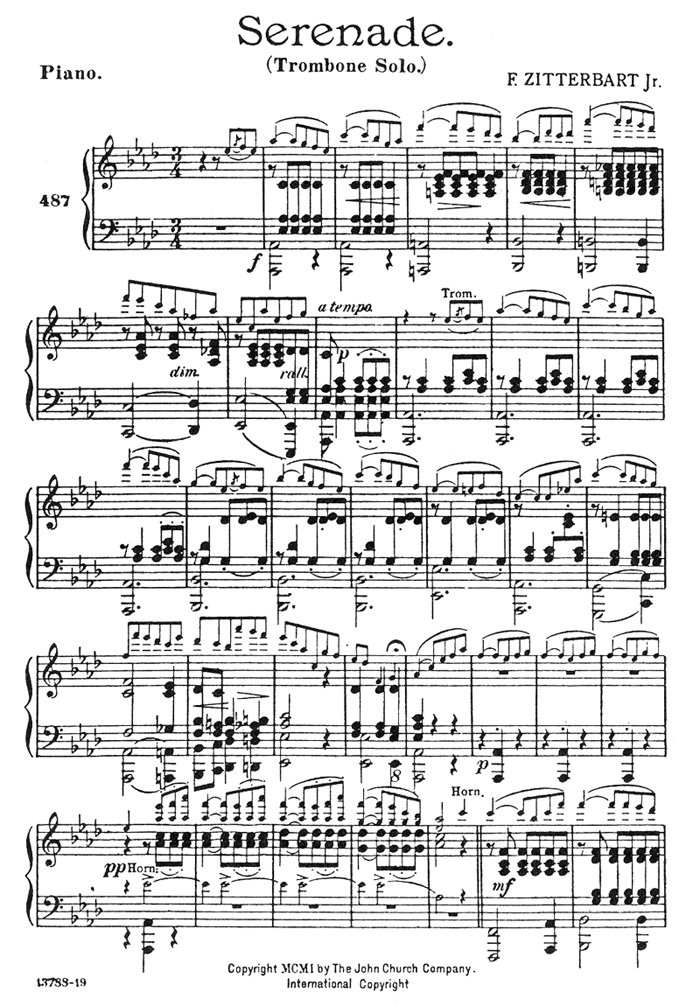

7It is not accurate to say that none of the compositions of Fidelis Zitterbart have been published. Although it is true that the composer was extremely reticent about permitting such publication, several of his chamber works did find their way into publishers' hands after Zitterbart's death. Edward Schuberth and Co. of New York offered several such compositions during the 1930's: a partial list would include Zitterbart's Duo Concertante in F Minor in three movements for two pianos; four short works for violin and piano: Imogen, Juliet, Musing, Preludio and Romanza. At least a few Zitterbart works were published during his lifetime. Unfortunately most if not all of these are popular, or salon type compositions which offer nothing more than the similar works of many other composers of the day. Not one of the ambitious compositions of Zitterbart, those so acclaimed by his contemporaries, was offered for publication during his lifetime. The John Church Company of Cincinnati published a few short works and most of these date from the last decade of the nineteenth century. One such work was Serenade, copyrighted in 1901 and listed as a solo for trombone or cornet and available with either piano or orchestral accompaniment (see Example 1).

Zitterbart's obituary claimed over sixty short, popular works of the composer to have been published prior to his death! It is possible that Zitterbart Jr.'s reticence concerning the publication of his music was, in part at least, an inherited trait. His father's ability as a composer will remain in question because of that individual's distrust of publishers. Thus the manuscripts of Fidelis Zitterbart Sr. gathered dust until late in his life when he destroyed them, fearing, it is said, a comparison with the compositions of his son!

8The beginnings of the cataloging process were undertaken by graduate students under Finney in the late 1960's. However, the retirement and recent death of this individual has placed the completion date of this project in question.

9Baynham claims these keyboard studies to have been popular among teachers of the instrument throughout the United States during Zitterbart's lifetime.

10"Working up a Strong Sentiment," Pittsburgh Leader, Feb. 18, 1900, "Pittsburgh Orchestra, 1896-1910," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

11"Musicians Scan Work of Fidelis Zitterbart," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 16, 1934, "Newspaper References: Pittsburgh Musicians. Fidelis Zitterbart," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

12Joseph J. Cloud, "Unplayed Symphony of Zitterbart Found," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Jan. 18, 1934, "Newspaper References: Pittsburgh Musicians. Fidelis Zitterbart," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

13"Fidelis Zitterbart," Program Notes: The Pittsburgh Symphony Society, Feb. 9, 1930, "Newspaper References: Pittsburgh Musicians. Fidelis Zitterbart," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

14A Minor string quartet; an E Minor Trio; Indian Dance for Violin/Piano; "Ben Hur" march; "A Norse Child's Requiem" were mentioned, among others.

15"Fidelis Zitterbart," Program Notes, Feb. 9, 1930.

16"Fidelis Zitterbart," Pittsburgh Press, April 22, 1934, "Newspaper References: Pittsburgh Musicians. Fidelis Zitterbart," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

17"Unearthed Music," Bulletin Index, Jan. 25, 1935, "Newspaper References: Pittsburgh Musicians. Fidelis Zitterbart," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

18See Holberg, p. 12, cols: 1-3. Also: Herbert Stein, "Pittsburgh's Forgotten Music Man," Pittsburgh Press and Sun-Telegraph, Sunday Magazine, July 31, 1960, pp. 19-20.

19William R. Mitchel, "Zitterbart," Pittsburgh Press, Feb. 9, 1930, "Newspaper References: Pittsburgh Musicians. Fidelis Zitterbart," Carnegie Library, Oakland Branch, Pittsburgh, Pa.

20The three-movement Faust suite is one of several Zitterbart works exhibiting a stamp indicating that it was at one time a part of the rental library of the National Broadcasting Company.