In writing musical biographies and in tracing the influence of one musical generation upon another, musicologists have traditionally spent considerable time and effort to investigate teacher-student relationships. Until recently this seems to have been impossible in the case of black ragtime composer Scott Joplin. Biographical sketches tell us that he was given his first formal musical instruction at about the age of eleven by a kindly German music teacher in Texarkana, on the Texas-Arkansas border. Joplin's surviving relatives, upon being interviewed however, could not remember the professor's name.1 One writer has referred to the teacher as "legendary,"2 while still another has said that his name was "lost in history."3 Before declaring the teacher "found," let us examine those details of Joplin's early life which bear upon this study.

Scott Joplin was born near the site of Texarkana, Texas-Arkansas, on November 24, 1868.4 Of his early musical activity, ragtime historian Rudi Blesh has written:

When barely seven, [Scott] discovered a piano in a neighbor's house, and was found surreptitiously experimenting with it. . . . Giles Joplin, though determined that his son learn a trade, scraped money together and bought a second-hand square piano. The boy was at this instrument day and night and before he was eleven years old he was improvising so remarkably that he became the talk of the Negro community. Rumors spread to the white community through servants' talk—Mrs. [Florence] Joplin was a laundress.

A German music teacher . . . in Texarkana . . . heard young Joplin play and as a result gave him free lessons in piano, sight reading, and the principles to extend and confirm his natural instinct for harmony. The professor is said to have played the classics for him and to have talked of the great composers and, especially, of famous operas.

Joplin's widow . . . was able to confirm the story of these events, [but] could not recall the name of the German teacher. . . . Joplin never forgot his first benefactor. In his later years (1907 to 1917), Mrs. Joplin said, he sent his teacher, by then ill and poor, gifts of money from time to time.5

In his Scott Joplin: The Man Who Made Ragtime, James Haskins recently identified the unknown teacher as Alfred Ernst, director of the Saint Louis Choral-Symphony Society, whom Joplin met in late 1900 or early 1901. Haskins based his identification, at first glance a very plausible one, on an article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of February 28, 1901, in which Ernst was interviewed concerning his discovery of Joplin's talent:

So deeply is Mr. Ernst impressed with the ability of the Sedalian [i.e., Joplin, who was then living in Sedalia, Mo.] that he intends to take with him to Germany next summer copies of Joplin's work, with a view to educating the dignified disciples of . . . European masters into an appreciation of the real American ragtime melodies. When he returns, . . . Mr. Ernst will take Joplin under his care and instruct him in the theory and harmony of music.

"I am deeply interested in this man," said Mr. Ernst to the Post-Dispatch. "He is young and undoubtedly has a fine future. With proper cultivation, I believe, his talent will develop into positive genius. . . .

"Recently I played for him portions of Tannhaeuser. He was enraptured. I could see that he comprehended and appreciated this class of music. It was the opening of a new world to him. . . .

"The work Joplin has done in ragtime is so original, so distinctly individual, and so melodious withal, that I am led to believe he can do something fine in compositions of a higher class when he shall have been instructed in theory and harmony.

"Joplin's work, as yet, has a certain crudeness due to his lack of musical concatenation, but it shows that the soul of the composer is there and needs to be set free by knowledge of technique. He is an unusually intelligent young man and fairly well educated."6

While Haskins investigated no further into Ernst's background, we shall do so. Alfred Ernst, aged twenty-six and considered a very talented pianist, was brought to Saint Louis from Germany in 1894 to become conductor of the city's Choral-Symphony Society.7 He proved to be an able, if excessively temperamental conductor, but found it "difficult to adjust himself to American ways." At the end of the 1906-07 season, he resigned his post in Saint Louis and returned to Germany to supervise the production of his operatic works.8 One of these, Gouverneur und Müller, a comic opera based on a Spanish story, was premiered in the Stadttheater in Halle in 1908.9 Alfred Ernst died of wounds suffered as a German soldier in World War I,10 leaving a widow11 and possibly children.

While Ernst probably did exert some influence over Joplin after 1900, especially in the area of opera,12 several elements in the foregoing material on the Saint Louis conductor do not correspond to Mrs. Joplin's recollections of what Scott must have told her. Joplin was supposed to have been about age eleven when he received his first formal instruction from the German in Texarkana; yet, when he met Ernst in Saint Louis, Joplin was probably thirty-two, had been to college, and was already a relatively successful ragtime composer. Joplin's immediate comprehension of opera when Ernst played some excerpts for him points to an earlier acquaintance with the medium. Furthermore, Joplin and Ernst were about the same age. Ernst never lived to be the ill and poor old man to whom Lottie remembered that Scott sent money; indeed the two men even died within a couple years of each other. For these reasons, I cannot accept Haskins's identification of Alfred Ernst as Joplin's first piano teacher.

Like Schliemann in search of Homer's Troy, I assumed the basic accuracy of Mrs. Joplin's recollections and returned to Texarkana in search for the identity of her husband's first piano teacher. If his lessons with the German began when Scott was about eleven, the year would have been about 1880, in which there conveniently occurred a United States census.

In June, 1880, when the census was taken, Texarkana (population circa 3250) could boast of three professional musicians.13 One, L.S. Kingsley, a white man, age thirty-four, had been born in Texas; his parents were from Vermont.14 Another was John Johnson, a mulatto, age thirty-seven, born in Louisiana. His father had been born in Indiana, his mother in Maryland.15 There is no apparent reason for Joplin, had he studied with either of these two, to have described him as a German to his wife Lottie. Therefore, both Kingsley and Johnson must be eliminated from consideration as possibly being Joplin's teacher.16

The third musician, however, was Julius Weiss, age thirty-nine, whose occupation was given as "Professor Music." He had been born in Saxony, as had his parents. A single man in 1880, Weiss lodged with R.W. Rodgers, a lumber manufacturer, and his family.17 While there is no absolute proof that Weiss was Joplin's teacher, the events in the following biographical sketch closely parallel those described by Joplin's family and provide strong evidence for such a conclusion.

Julius Weiss was born in Saxony, probably sometime between June 4, 1840, and June 3, 1841. Both of his parents had also been born in Saxony.18 If he was typical of the potentially educated classes, he was probably graduated from a Gymnasium in or near his home town sometime about age nineteen.19 This would have been 1860. Several years later, Weiss was graduated from the "University of Saxony," as one of his later students20 recalled the name of the institution.21 In addition, he must also have had some private or conservatory instruction in music.

When and why Weiss left Germany and came to the United States is a matter for conjecture. He may have been in danger of conscription during the Six Weeks' War in the summer of 1866 or for the Franco-Prussian War several years later. If so, he was not the only educated German to flee Bismarck's militaristic policies. He probably arrived through the port of New York and, in one of several stops of indeterminate length,22 made his way through the Midwest to Saint Louis, where he lived for less than a year23 before being engaged by Col. Robert Wooding Rodgers of Texarkana to be a teacher there.

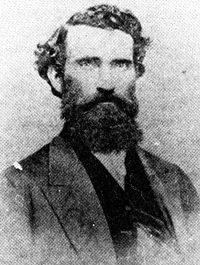

R.W. Rodgers (Figure 1) was born in Tennessee in 1820, and moved to Missouri in 1837.

Figure 1. Col. Robert W. Rodgers, employer of Julius Weiss in Texarkana.

Courtesy of Mrs. Lelia D. Barrett.

There he went into the lumber business and wed Miriam Stark in 1842. Four of their nine children survived: Benjamin, Mary, Sara, and Virginia (Figure 2), called Jennie by the family.

Figure 2. Virginia Rodgers Daley, piano student of Julius Weiss.

Courtesy of Mrs. Lelia D. Barrett.

When his wife died, Rodgers married Frances J. Montgomery (born 1837) in July, 1861. During the Civil War, Rodgers was appointed a colonel in the Confederate Army and, as quartermaster, was sent in Texas. In 1866, he moved to Jefferson, Texas, and built a sawmill there.24

To the second Rodgers union were born eight children, of whom Lelia, Rollin W., Thomas, Joseph D., Leo A., and Frances G. survived childhood.25 Although the family had adhered to no particular religion in the past, the second Mrs. Rodgers was so impressed by the level of education among the nuns at the parochial school in Jefferson that she and the children joined the Catholic Church in 1870.26

In December, 1873, Rodgers became one of the first landowners in the newly founded town of Texarkana, straddling the Texas-Arkansas border, and began clearing lots for the settlers.27 The railroad, which had reached Texarkana, enabled Rodgers to ship his lumber to Saint Louis more easily and acted as a magnet for new residents. Among those who sought railroad jobs was surely Giles Joplin and his family.28

Probably through his wife, Rodgers became a strong champion of education. Sacred Heart Catholic Church, founded early in 1874, was the first to provide a school, attended by Catholic and non-Catholic children. The first teacher, in September, 1874, was Miss Maggie Wilson,29 whom Rodgers had hired during a trip to Saint Louis.30 At first, school was held in a boarding house, the Carey Hotel, but later was temporarily moved to the dining room of the Rodgers residence while the lower floor of the church (only a block away) was being prepared to accommodate classes. Miss Wilson was followed by Miss Robertson in 1875-76, by Miss Duffee and Mr. Delaney in 1876-77, and Miss Palmer in 1878-79.31 After several years of seeing young maiden school teachers come to town, only to marry and leave by the next year, Rodgers asked the Catholic bishop to send five nuns,32 who opened Saint Agnes' Academy in September, 1879. In the meantime, several other private schools had been established and led to the demand for public schools. On September 28, 1878, Judge James Hubbard of Bowie County issued R.W. Rodgers a commission appointing him "Trustee of Texarkana, No. 1 School, Community No. 14." Nevertheless, public schools were not initiated until several years later.33

Because he seems to have held no official position, Julius Weiss is not mentioned among these early teachers in Texarkana. Rodgers evidently engaged him to supplement his children's institutional education and, as Mrs. Rodgers herself said later, "so my children could continue the excellent musical training they had received from the Sisters in Jefferson."34 Like the other teachers, Weiss was hired from Saint Louis, but when? It is conceivable that Rodgers hired him in time for the 1877-78 school year when, unlike the year before, the Catholic school seems to have had only one teacher. Weiss could also have been hired just before the 1878-79 school year when, as we have seen, popular sentiment was running high in favor of public schools. Perhaps Rodgers, appointed trustee late in September, 1878, saw in Weiss a potential teacher for the proposed public school. The immediate problem of a teacher shortage seems to have been solved by September, 1879, so it is doubtful that Weiss would have been engaged when the city was expecting five nuns. It is reasonable, therefore, to conclude that Weiss arrived in Texarkana between August, 1877, and December, 1878, perhaps in time to begin teaching in September of either year.

Professor Weiss's teaching duties were varied, if the subjects he taught Rollin Rodgers are any indication. Under his tutelage, Rollin learned German, astronomy, and mathematics.35 All of the boys in the family, including Rollin, learned violin. The professor also laid the groundwork for Rollin's lifelong interest in opera, the significance of which may be seen later. The family girls all studied piano; Virginia and Lelia were the best pupils.36 In addition to family members, Weiss also taught music to others among the town's children. Mamie Bruhn, a friend of Virginia's, was one of his piano students. The instruction took place in the parlor of the Rodgers home (Figure 3) on the southwest corner of Maple and Clinton Streets (now Texas Avenue and Third Street).37

Figure 3. The Rodgers home, fronting on Maple Street, Texarkana, Texas.

Courtesy of Mrs. Lelia D. Barrett.

The family piano was an old square model which had been brought with them from Jefferson. At some time during his tenure, Weiss convinced Col. Rodgers that a new one was needed. Rodgers sent Weiss to New Orleans to purchase a new instrument: a square grand, made of cherry wood, with a lyre pedal and mother-of-pearl keyboard. The acquisition was made while Virginia was away at school in Springfield, Missouri. When she returned home, she was dismayed to find that the old piano, to which she had a sentimental attachment, was gone.38

One tangential aspect of Weiss's character will be considered here, that is, his religion. His name is not a definite clue. Weiss was a common enough surname and the given name Julius could have been bestowed by classically-minded parents of any religious persuasion. If he was a Christian coming from Saxony, chances are that he was a Protestant. By association, however, there is evidence that he might have been Jewish. The Rodgers home had ten bedrooms.39 In 1880, these were inhabited by Col. and Mrs. Rodgers, seven children ranging in age from one to twenty, perhaps one female "companion," and five male tenants. Probably some of the tenants shared rooms with each other. Among these tenants (and in fact listed in the census on the line immediately above Julius Weiss) was Joseph Deutschmann, age thirty-three, an unmarried real estate agent from Poland.40 A prominent member of the early Jewish community in Texarkana, Deutschmann was secretary of the Hebrew Benevolent Association by 1884,41 and was one of two respected leaders who held services prior to the organization of Mount Sinai Congregation in 1885.42 It is possible that these two immigrants (the only foreigners among the Rodgers tenants) shared not only a room, but also a common religious heritage.43 As we shall see, however, Weiss had probably moved from Texarkana before Mount Sinai was formally organized.

Col. Rodgers died on April 14, 1884.44 Mrs. Rodgers had to sell the three sawmills in order to support her family, and doubtless had to make other adjustments corresponding to the family's reduced income.45 Certainly she could no longer afford a semi-private tutor and music teacher in the house. Whether she had to terminate Weiss's employment, or whether he resigned to spare her the duty of doing so, Weiss had probably left town by August, 1884. At this time, surviving newspapers provide a few glimpses of Professor Johnson's musical activities, as well as preparations for the opening of the Fall semester in the various city schools, including an English-German School, operated by W.F. Thurm, Ph.D. Nowhere is Weiss mentioned, either as a musician, music teacher, or as a general school teacher.46 It is probable, then, that he left Texarkana sometime between April and August, 1884.47

Weiss's whereabouts for the next decade are unknown. Possibly he taught music and/or general subjects in one of the many small towns in East Texas. Or he may have migrated to any of the many cities and towns within a triangular area, roughly formed by Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, in which there lived a large German population.48

In about 1895, Julius Weiss, presumably our subject, became the junior partner of W.C. Stansfield and Co. in Houston, Texas. Their business, which sold pianos, organs, and music, was located at 603 Main Street. Weiss, evidently still single, rented at 1614 Travis Street.49 By 1897, they had dissolved their partnership. Stansfield still maintained the piano and organ business, now located at 615 Travis, but Weiss was listed in the city directory as a "music teacher," renting lodgings at 1903 Travis Street, corner of Calhoun Avenue.50 In the directory for 1899, Stansfield remained as proprietor of the Piano Exchange, 615 Travis, but Weiss had disappeared from its pages.51 The reason why may be found the next year.

The Houston Directory for 1900-01 listed Julius Weis [sic] as being "with Perkins and Buchanan," and rooming at 508 LaBranch Street. Neither here, nor under Perkins and Buchanan, William H. Perkins, or Hamilton Buchanan is there any indication of the nature of their business, which was conducted "over 406 Main."52 In 1894, W.H. Perkins & Co. (of which Buchanan was already a partner) had operated "Club Rooms" at 319 Travis Street.53 Was this a euphemism for a business whose nature would have been unspoken (although widely known) in a different location six years later? In 1903, W.H. Perkins & Co. (now minus Buchanan) was noted as being "over '66,' 406 Main."54 Sixty-six is a card game!55 The 1900 Census56 confirms our suspicions: Perkins and Buchanan operated a gambling establishment! Perhaps Weiss played piano to entertain the customers.57

That Weiss had fallen upon hard times is further confirmed by examining the 1900 Census listing for the house at 508 LaBranch where, as the Directory indicated, he roomed. The principal renter of the house was Henry Carstons, age fifty-eight and married. His occupation was given as "gambler."58 With him lived his wife and her daughter by a previous marriage. They had three roomers, one of which was Henry Kiss, age twenty, for whom no occupation was given. The second was John Farrall about whom nothing was known (or told to the census taker). Details about the third roomer, listed as "Julius Ulkus" [sic], were likewise unknown. Whoever supplied the information to the census taker (perhaps Mrs. Carstons or the roomer Kiss) did not even know Weiss's name well enough to repeat it properly.59

This sad note is the last personal reference we have to Julius Weiss. He did not appear in any Houston Directory after 1900-1901. He could have left town for an unknown destination, or he could have died a derelict.60 Perhaps the final word on Weiss has come from Scott Joplin's widow. She said that "in [Joplin's] later years (1907 to 1917), he sent his teacher, by then ill and poor, gifts of money from time to time," until "the older man died."61 How did Joplin know his whereabouts? Had they kept in contact for twenty years, or could Weiss, learning of his student's relative success, have written to him and requested financial assistance?

Rather than dwell upon this image of Weiss in old age, let us return to Texarkana once again and see how this teacher, then in his prime, might have influenced and inspired the young Scott Joplin. During at least some of Joplin's early years in Texarkana, his family lived in the 600 block of Hazel Street, in the Arkansas section of town.62 Barely a block away, on the southeast corner of Sixth and Laurel Streets, was the residence of attorney W.G. Cook,63 whose family had a piano in its parlor. Florence Joplin is reputed to have done cleaning and washing there and brought Scott with her. The youngster had free use of that piano during his formative years.64 This seems to corroborate the story (cited earlier)65 that "when barely seven, Joplin discovered a piano in a neighbor's house, and was found surreptitiously experimenting with it."66

We will probably never know the exact chronology of the succeeding events. Rumor of the child's gifts spread through the black neighborhood and "to the white community through servants' talk." Perhaps Florence Joplin also did laundry for the Rodgers family, although Frances Rodgers probably had enough daughters to help out. Even so, Joplin's mother might have done laundry for the single male tenants, among whom was Julius Weiss.

"Giles Joplin . . . scraped money together and bought a second-hand square piano."67 At best father Joplin probably earned a subsistence wage, nor was he reputed to have been the most loyal of family men.68 Even with his own musical bent, Giles was probably not inclined to spend an excessive amount of money for so obvious a luxury. In addition, there were surely very few second-hand pianos for sale at any price in Texarkana during this period; remember that the town was still less than a decade old! The solution is obvious. Somehow Giles bought for a small sum, or was given, or was allowed to pay in labor69 for the Rodgers family's old square piano which disappeared after Julius Weiss selected their new one. Could the acquisition of the piano have occasioned the kindly Weiss's first audition of the black boy's playing, or could young Scott have been studying with him even earlier? If Weiss already knew Scott, perhaps he induced Rodgers to sell the piano to Giles at a reduced price. Again the sequence of events is uncertain.

In any case, it was surely Weiss who gave Joplin those "free lessons in piano, sight reading, and the principles to extend and confirm his natural instinct for harmony." It was surely Weiss who "is said to have played the classics for him and to have talked of the great composers and, especially, of the famous operas." Indeed, did he not also make an opera lover out of Rollin Rodgers?70 And might he not also have tutored young Joplin in academic subjects, just as he did with the Rodgers children?71

How long did Joplin remain in Texarkana? The traditional story is that he departed in "about 1882, when he was about fourteen."72 By this time, Scott may have had only about two or three years of study with Weiss. What we know of his later playing and knowledge indicates the results of more than a departure in 1882 would allow. If Giles was not an ideal father, Joplin may have found a substitute in his teacher, in his intellectual "parent." And Joplin would probably not have left Texarkana while Weiss was there unless absolutely forced to. Once Weiss departed, sometime between April and August, 1884, there was little to keep Joplin, now fifteen, in Texarkana.

I believe that the composer gives us the answer to his own departure date in his opera, Treemonisha, with whose heroine, an educated black, Joplin obviously identified. In the final two sentences of the Preface, Joplin tells us, "The opera begins in September, 1884. Treemonisha, being eighteen years old, now starts upon her career as a teacher and leader." Thus, the action of the opera is set only a few months after Julius Weiss left Texarkana. September, 1884, a date so significant to Joplin that he specified it exactly in his Preface, is very possibly the month and year when he himself departed Texarkana, to "start upon his career as a teacher and leader."

1Rudi Blesh, "Scott Joplin: Black-American Classicist," in Scott Joplin, Collected Works, ed. by Vera Brodsky Lawrence, 2 vols. (New York: New York Public Library, 1971), I, xiv. In 1949-50, Blesh and Harriet Janis had interviewed Joplin's widow, Lottie Stokes Joplin; he also quotes interviews with the son and daughters of Scott's brother, Monroe, conducted by Addison W. Reed in 1971. Blesh and Janis, in their earlier They All Played Ragtime, revised edition (New York: Oak Publications, 1971), p. 37, mention the German teacher, while Reed was evidently told nothing about him. In "Scott Joplin: Pioneer," The Black Perspective in Music III (Spring, 1975), 48, 52, Reed attributes the tale of the German to Blesh-Janis, and notes disparagingly that his existence had never been substantiated.

2Vera Brodsky Lawrence, "Scott Joplin and Treemonisha" (in libretto pamphlet), Joplin, Treemonisha, recording, Houston Grand Opera Production, conducted by Gunther Schuller; DGG 2707 083.

3E. Power Biggs, liner notes, Scott Joplin on the Pedal Harpsichord, recording; Columbia M32495.

4The town of Texarkana was not laid out until December, 1873. Recently, Charles Steger, a local historian in Longview, Texas, discovered the Joplin family in the 1870 Census, living in the Cave Springs community, two miles west of Linden, Texas, and therefore about thirty-five miles southwest of the present Texarkana. Steger reported his findings in Texas Monthly (October, 1977). Interview, Jerry Atkins, Texarkana, December 20, 1977. Atkins is a local historian and ragtime enthusiast. This information was used by James Haskins in his Scott Joplin: The Man Who Made Ragtime, with Kathleen Benson (Garden City: Doubleday, 1978), pp. 30-33.

5Blesh, "Joplin, Classicist," p. xiv. In his narrative, Blesh combines material gathered from Monroe's children and Scott's widow, without always making clear the source of each element. I do not paraphrase Blesh at this point (and change only a few details, as noted) because several later conclusions will be based upon the supposition that Blesh's account reflects the terminology and chronology given in the several interviews. In They All Played Ragtime, p. 37, however, Blesh offers several variants. He calls the teacher "old" and says that Joplin sent the German money until the older man died. A man very advanced in years when he taught Joplin would probably not have survived until the black man's own last decade. We must therefore conclude that the teacher in Texarkana was a younger man than has heretofore been supposed.

6Haskins, Joplin, pp. 112-113.

7Ernst C. Krohn, "The Development of the Symphony Orchestra in St. Louis," Proceedings of the Music Teachers National Association XVIII (1924), 81-82. The Choral Society, founded in 1880, later became the Choral-Symphony Society, and was the immediate predecessor of today's Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra.

8John H. Mueller, The American Symphony Orchestra (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1951), p. 146.

9W.L. Hubbard, The American History and Encyclopedia of Music (New York: Irving Squire, 1908), II (Operas), 368; confirmed in Neuer Theater-Almanach, 1908 (Berlin: F.A. Günther & Sohn, 1908), p. 393. One could guess that the plot was on the three-cornered hat theme.

10Mueller, Orchestra, p. 146.

11Krohn, "Development," p. 86. One of Krohn's acknowledged sources for his article was Mrs. Alfred Ernst, presumably the wife of the conductor.

12A diligent researcher who could locate Ernst's descendants or the location where Ernst's collection of scores was deposited after his death might possibly find a copy of Joplin's lost opera, A Guest of Honor.

13U.S. Census, 1880, Bowie County, Texas; Miller County, Arkansas. The Texas side of the town had ca. 1850 residents; the Arkansas side, ca. 1400.

14Census, Texarkana, Texas, p. 48D.

15Census, Texarkana, Texas, p. 34C.

16Haskins, Joplin, pp. 53, 60, 206, believes Johnson to have been Joplin's Texarkana teacher, and conjectures much from his unsubstantiated belief. Without specific documentation, Haskins writes that Johnson was "variously remembered as a mulatto, a Mexican, 'Indian-looking' and partly of German descent," surely an extensive ethnic heritage for any one man! If there was any German blood in Johnson (which seems unlikely when one considers the prevalent German-American social attitude in the early nineteenth century), it is certainly not evident in the birthplaces of his parents. Haskins writes that Johnson played "in the classical style" and quotes one elderly Texarkanan who did not think that Johnson played for dances. The latter supposition, at least, is disproven by the Daily Texarkana Independent, August 21, 1884, which noted a "hop" on the previous evening, at which Prof. Johnson furnished the music. He must have done likewise on many similar occasions. Haskins also notes that, through his real estate holdings, Johnson eventually was considered relatively wealthy by Texarkana blacks. It seems, then, that Johnson would hardly have needed the monetary gifts which Joplin supposedly sent his financially distressed former teacher at a later date. It must also be noted in passing that Haskins himself seems not to have visited Texarkana during the course of his research, as I did on two occasions.

Another improbable candidate was a Mr. Hardler, who taught zither in Texarkana in about 1895. Hardler, however, does not seem to have been in town early enough to have known Joplin. (Atkins, Interview).

17Census, 1880, Texarkana, Texas, p. 36D.

18Census, 1880, gave his age as thirty-nine, which would place his birth in this time span. If, however, he was "in his thirty-ninth year," an age interpretation often given to census takers, his birth would fall between June, 1841, and June, 1842. The exact town of his birth has not been determined.

19Robert H. Lowie, The German People: A Social Portrait to 1914 (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1945), pp. 42-43.

20"Rollin W. Rodgers," in Barbara Overton Chandler and J. Ed Howe, History of Texarkana and Bowie and Miller Counties, Texas-Arkansas (Shreveport, La.: Howe, 1939), p. 352. This biographical sketch was doubtless prepared by Rodgers himself, typical of those included in "who's who" sections of local histories.

21Weiss could have studied at any of three universities within the somewhat indefinite borders of Saxony, those at Halle, Jena, and Leipzig. Letters from Dr. Schwabe, archivist, Martin-Luther-Universität, Halle, May 23, 1978, and Dr. Wahl, archivist, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität; Jena, May 26, 1978, indicated that Weiss's name does not appear on their students records from 1858 to 1870. Both pointed to the University of Leipzig as being the likely "University of Saxony" which Weiss attended, but a similar letter from the archivist, Karl-Marx-Universität, Leipzig, June 6, 1978, indicates that he did not study there either.

22In the Louisville (Kentucky) City Directory, 1868-69, p. 419, is a cryptic entry, "Weiss,—[no first name], r. 170 Jefferson, between Preston and Jackson." Mark Harris, Louisville Public Library, March 13, 1978, wrote that this entry was not repeated or clarified in any earlier or later directory. Still, this Weiss could have been our Julius, as he appears to have been unrelated to the several Weiss families (including one Charles Weiss and his daughter Julia, coincidentally both music teachers) living in Louisville at the time. Julius could also have entered the United States at New Orleans, a port through which many Germans immigrated.

23A survey of the Saint Louis City Directories for each year from 1873 to 1881 indicates only one Julius Weiss, but he manufactured ladies' underwear and remained in Saint Louis during the years our subject resided in Texarkana. The Library of the Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio, and its reference librarian, Mrs. Virginia Hawley, have provided me with an amazing number of city directories from the nineteenth century, including many for Saint Louis. Leland Hilligoss of the Saint Louis Public Library provided me with information from the few directories I lacked.

24"Col. Robert W. Rodgers" and "Mrs. Frances J. Rodgers," in Chandler and Howe, History of Texarkana, pp. 276-77, 321. Their biographies were probably prepared by son Rollin W. Rodgers.

25"Mrs. Rodgers," pp. 277, 321. In the 1880 Census, the children's ages are: Jenny, 20; Lelia, 14; Rollin, 12; Tom, 10; Frances G., 8; Joseph, 3; Leo, 1.

26Lelia D. Barrett, Interview, Texarkana, December 20, 1977. Mrs. Barrett, the daughter of Virginia Rodgers Daley, and a retired teacher, was a keen-minded eighty-seven year old when I talked to her.

27"Col. Rodgers," p. 276.

28Barrett, Interview.

29Chandler and Howe, History of Texarkana, pp. 159-160.

30Barrett, Interview.

31Chandler and Howe, History of Texarkana, p. 160.

32Barrett, Interview.

33Chandler and Howe, History of Texarkana, p. 160.

34Barrett, Interview, quoting her grandmother.

35"Rollin W. Rodgers," p. 352.

36Barrett, Interview. Rollin's progress on the violin was slow, and he was often sent, violin in hand, to tend the cows in their pasture, so the family would not have to hear his practice. Nevertheless, in later business trips to New York as an attorney, Rollin found that he had sufficient knowledge of opera to hold his own among those of his colleagues who were also opera lovers. In conversation, Mrs. Barrett always referred to the teacher as "Professor Weiss," just as her mother, Virginia, had done. "Professor" was a common term for teachers, but was guarded with special zeal by central European immigrants. Note that Joplin's teacher was remembered as "professor." Weiss must have been a kind man, as well as a fine teacher, because a genuine affection and respect for him have survived two generations, judging from Mrs. Barrett's accounts.

37Barrett, Interview. Census, 1880, Texarkana, Texas, p. 37B, tells that Mamie A. Bruhn was born in Louisiana in about 1884. Her father was A. Bruhn, a Danish immigrant merchant, born about 1829.

38Barrett, Interview. There is also a possibility, according to Mrs. Barrett, that the new piano came from Saint Louis. In any case, Weiss was sent to select it.

39Barrett, Interview.

40Census, 1880, Texarkana, Texas, p. 36D.

41Daily Texarkana Independent, August 18, 1884, p. 2. Under a heading of local societies, the notice for the Hebrew Benevolent Society ran continuously for some time after this date.

42Chandler and Howe, History of Texarkana, pp. 157-158. The other leader was Marks Kosminsky, born in Poland in about 1844. The services were held in Kosminsky Hall, probably part of his dry goods store. Census, 1880, Texarkana, Arkansas, p. 101B.

43While Deutschmann's name appears frequently in the early written records of Mount Sinai Congregation after its organization in 1885, that of Julius Weiss does not appear at all. Telephone conversation with Rabbi Joseph Levine, Texarkana, January 11, 1978; Rabbi Levine had examined the early documents in search of Weiss's name.

A letter survey of the Catholic and Lutheran churches in Texarkana revealed no mention of Weiss; the Lutherans did not organize until after 1900. Pastor W.M. Putman, Christ Lutheran Church, is past president of the local genealogical society, and took considerable time and effort to locate for my interviews those people (including Mrs. Barrett) who might have had information on Weiss or Joplin.

44"Col. Rodgers," p. 321.

45Barrett, Interview.

46I have found no surviving local newspapers earlier than the Daily Texarkana Independent, August 18, 1884. I thoroughly examined all copies through mid-September, and cursorily glanced at others through October, 1884. The cited information was published on August 18, 19, 20, 21, and September 3, 1884.

Weiss had surely departed by 1885, when Virginia Rodgers married Thomas Daley. Again the evidence is due to an omission. Mrs. Barrett is sure that, had Weiss played for her parents' wedding in Sacred Heart Church, her mother would have mentioned the fact among her stories of the event.

47Due to courthouse fires, official records for the period of Weiss's residence in Texarkana are very few. Even so, they would probably not show his name: he was single and seems not to have married; he owned no real estate, and probably owned nothing else that was taxable; due to lax naturalization laws, he may never have become a citizen; and since he did not die in Texarkana, there would have been no official record of his death or will.

48See my dissertation, "German Singing Societies in Texas" (North Texas State University, 1975), for historical background on the German element in Texas and their musical activities. The same triangle mentioned above contained many Czech settlements in which Weiss might also have been able to make a comfortable living. The itineraries of Joplin's Texas Medley Quartette tours, if ever precisely determined, might provide a clue to Weiss's whereabouts during this decade.

49Houston Directory 1895-96 (Galveston: Morrison and Fourm, 1895), pp. 345, 318, 393. They were one of four piano and organ dealers in Houston. William C. Stansfield, who lived at 1014 Travis St., was probably the son of John W. Stansfield. As early as 1882, W.C. had worked as a bank teller; in 1887, he was a wood dealer, but by 1894 was a bookkeeper for W.J. Hancock, Jr. Throughout this period, he lived at his father's address. Houston Directory, 1882-83, p. 269; 1887-88, p. 292; 1894-95, p. 504. Weiss was not listed in any directory before 1895-96 for which the information had been collected between November, 1894, and October, 1895. From this we can see that in 1895 (or at the earliest, during the year before) Stansfield changed his occupation and went into business with Julius Weiss, himself newly arrived in town. That Stansfield was once in the lumber business, the same as Rodgers had been, is probably a coincidence, an interesting one. The name of neither man is listed under "Music Teachers" in the 1895-96 Directory, p. 390.

50Houston Directory, 1897-98, pp. 269, 294, 336, 340. Weiss was now cross-indexed under "Music Teachers," although Stansfield was not. Margaret Newton and Mrs. L. Jeter of the Houston Public Library helped me to locate this information.

51Houston Directory, 1899, p. 278. Stansfield was to remain in this business for many more years.

52Houston Directory, 1900-01, pp. 346, 255, 256, 49. There had been no "Julius Weis" in any earlier directories, so we can only conclude that this man is our subject. The firm of Perkins and Buchanan is listed in bold print in the directory.

53Houston Directory, 1894-95, pp. 427, 134, 595.

54Houston Directory, 1903-04, p. 344.

55"Sixty-six," Webster's New International Dictionary, 2nd ed., unabridged (Springfield, Mass.: C. & G. Merriam, 1951), p. 2351.

56U.S. Census, 1900, Harris County, Texas, vol. 53, enumeration district 71, sheet 2, lines 92-93, list H. Buchanan, age fifty-nine, occupation: gambler. The same census, vol. 53, e.d. 79, sheet 1, lines 49-50, list W.H. Perkins, age forty, as a real estate agent.

57The remote possibility remains that they had a legitimate real estate operation of some sort on the premises, and that Weiss was an agent for that business. Such a concern would naturally command bold print in the directory, but its nature would just as surely be identified for prospective clients.

58In Houston Directory, 1900-01, p. 59, his name was given as Carstens, and his occupation, an ambiguous "with Barney Cornelius."

59Census, 1900, Harris County, Texas, vol. 53, e.d. 75, sheet 10, line 74. That census could have told us the month and year in which he was born, as well as confirmed his birthplace and occupation, or indeed his identity as Julius Weiss, the subject of this paper. Many of the spaces after "Ulkus's" name are blank. Several simply read "Unk[nown]." The blame for this confusion cannot be placed on the census taker himself, who seems in other instances, to have been as conscientious and accurate as possible.

60I have checked many possibilities attempting to find a death certificate for our subject: death records for the state of Texas, 1903-40; double checking in Houston specifically through 1920. I visited the old German cemetery in Houston with no results. Weiss did not die in Missouri, at least to 1937. If he died in Louisiana, the state will not divulge that information except to direct descendants.

61Lottie Stokes Joplin, quoted in Blesh, "Joplin, Classicist," p. xiv, and They All Played Ragtime, p. 37. Blesh's conjecture that Joplin may have visited his teacher on a possible trip to Texarkana in 1907 can now be seen as unsupported. Weiss probably never returned to Texarkana after he left in 1884.

62Jerry Atkins, "Scott Joplin—American Master Composer," Texarkana Centennial Historical Program, compiled by Nancy Watts Jennings and Mary Lou Stuart Phillips (Texarkana: [Texarkana Historical Society and Museum], 1973), p. 34. Atkins, Interview. Atkins believes the house to have been on the east side of Hazel, the second lot south of Seventh Street. Today (1978) that lot is vacant and serves as a parking lot for the Jamison Sanitarium, immediately to the south of it. The 1880 Census, in which the Joplin family is recorded in the Texas list, p. 47A, but not in the Arkansas, seems to contradict Atkins. Census takers were notorious, however, for disregarding state or county borders, and this one seems to have been particularly lax about entering the street locations required on the forms. Haskins, Joplin, pp. 54-55, however, believes that the Joplins did not move to Hazel Street from the Texas section of town until after 1880, a definite possibility. On Texarkana, Texas and Arkansas: Perspective Map (Milwaukee: Henry Wellge [ca. 1888]), the house appears to be a two or three room structure with a lean-to (probably a kitchen) at the rear.

63Nona Stickney, telephone conversation, Texarkana, January 11, 1978. Mrs. Stickney is the daughter of Jean Cook and the granddaughter of W.G. Cook.

64Atkins, Interview. Atkins's information evidently came from Jean Cook, W.G.'s son.

65The following quotations are taken from Blesh, "Joplin, Classicist," p. xiv, quoted earlier in this article. The citation will be understood, and will not be repeated in this context.

66Compare this Blesh passage with one which Joplin wrote in the Preface to his opera, Treemonisha: "When Treemonisha was seven years old Monisha arranged with a white family that she would do their washing and ironing and Ned would chop their wood if the lady of the house would give Treemonisha an education."

67Reed, "Joplin: Pioneer," p. 47, and Haskins, Joplin, p. 58, assign the purchase of the piano to Florence, the former author for no more apparent reason than an attempt to discredit Giles. Indeed Haskins erroneously credits Blesh for having written that Florence purchased the piano.

68Atkins, Interview. Haskins, Joplin, pp. 54-55, corrects the earlier assumption that Giles had deserted the family when Scott was a young child, and demonstrates that the family was intact as late as 1880. This is, of course, confirmed in the census for that year, p. 47A.

69In the Preface to Treemonisha, Joplin wrote that his heroine's father chopped wood for a white family as partial payment for Treemonisha's superior education. We know that Col. Rodgers owned sawmills in Texarkana at this time. Perhaps Giles Joplin took a temporary second job, "chopping wood," at a Rodgers sawmill to work off the debt incurred by the purchase of the piano.

70When Alfred Ernst played selections from Wagner's Tannhäuser for him in 1901, Joplin already "comprehended and appreciated this class of music." Haskins, Joplin, p. 112.

71Whatever the strengths or weaknesses of Texarkana's Negro schools during this period, Joplin had sufficient education to enter the George R. Smith College for Negroes in Sedalia, Missouri in 1896. Blesh, "Joplin, Classicist," p. xix.

72Atkins, Interview, believes that Joplin did not leave Texarkana until about 1885. Haskins, Joplin, p. 62, places his departure in 1888.