O what music there will be in Chicago

From Yankee Doodle thro' to Handel's Largo.

The orchestras will play

And the brass bands too, they say,

For that great Columbian Fair at Chicago.

We'll hear such melodies with grandest chords and harmonies

When the singers gathered there shall raise their voices,

For the greatest jubilee that we ever yet did see,

And that is why America rejoices.

—"Are You Going to the Fair at Chicago" by C. Ormsbee Gregory, verse 3

The World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus's landing in the New World, marks a milestone in the history of American music. But ironically, the grandiose musical plans for the fair were a notable failure, and some of the most influential music heard there, ragtime, was never mentioned in the press or official histories.

Planning for the music at the fair began auspiciously when Theodore Thomas was appointed music director in 1891. Thomas had been a leading figure in American music for over thirty years. At the time of his appointment, he had recently arrived in Chicago as founding director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Serving with him on the fair's music bureau were choral conductor William L. Tomlins, who had been director of Chicago's Apollo Music Club for nearly twenty years, and secretary George H. Wilson of Boston.

Although Thomas was widely regarded as the finest orchestral conductor in the country, he was a controversial figure. Some of his projects had been financial disasters. His aloofness and uncompromising standards had earned him powerful enemies wherever he had lived. Thomas had built his career on challenging and educating public taste. From his earliest days as a conductor, he had programmed music that was a little bit beyond the audience's comprehension in the hope that they would catch up to it.

Thomas was guided by two central ideas, which are contained in a statement issued by the music bureau June 30, 1892:

- To make a complete showing to the world of musical progress in this country in all grades and departments, from the lowest to the highest.

- To bring before the people of the United States a full illustration of music in its highest forms, as exemplified by the most enlightened nations of the world.1

Thomas did not finish the work he began. He ran into trouble even before the fair started by ignoring an order to compel Ignace Paderewski to play a locally made piano instead of his Steinway.2 In addition to his traditional enemies, therefore, he aroused the opposition of certain local businessmen, the political hacks who ran the fair, and several newspapers. The nastiest and most strident of these was the Chicago Herald, which actually fired a critic for writing rave reviews of Thomas's early performances.3 (Unfortunately, no other Chicago newspaper matched the Herald for its breadth of coverage of the fair's music.) For three months, Thomas worked against a background of constant sniping about his fondness for Wagner, his supposedly dictatorial manner and his stubbornness. When his salary became a matter for editorial controversy and his personal integrity was questioned, he decided that he had suffered enough. Effective August 12, he resigned.

Before the opening of the fair, the bureau of music announced the following classifications of concerts:

- Popular orchestral concerts

- Symphony concerts

- Festivals, with chorus, orchestra, and eminent soloists

- Concerts by famous visiting orchestras, bands, and choral societies from other cities

- Concerts by famous European or American artists and composers exhibiting their own works

- Open air band concerts

- Chamber concerts

- Amateur concerts.4

The compendium of official programs shows that the orchestral and choral concerts were grouped into three major series, two of which were simply named for the building where they were presented. The Music Hall Series consisted of 37 concerts: 16 by the Exposition Orchestra, 4 by visiting orchestras, 8 by the Lineff Russian Singers, 7 by other visiting choruses, one ballad concert, and a performance of Mendelssohn's Elijah by the World's Columbian Chorus. The Festival Hall Series, 28 concerts, included 21 by various choruses, 5 devoted to the music of Wagner, and two of miscellaneous orchestral pieces, which will be counted among the popular concerts. The Popular Music Series was actually numbered in three series, depending upon where the concerts were performed: 53 in Festival Hall, 2 in the Woman's Building, and 2 in a lakefront music pavilion.

Symphony concerts

While the symphony concerts were second on Thomas's list, they were surely first in his heart. Besides the five all-Wagner concerts on the Festival Hall series, there were concerts devoted entirely to the works of Schubert (May 5), Brahms (May 9), Beethoven (May 12), Joachim Raff (May 26), and Schumann (June 9). Three concerts (May 23, July 6, and July 7) were devoted entirely to American music. A fourth (August 4) was mostly American music. The remaining 7 concerts featured works of 19 different composers. Music of Beethoven and Liszt was heard on 4 of these, Bruch and Tchaikovsky on 3, Mozart and Schumann on 2. In all, 34 composers were represented on the symphony concerts: 12 Germans or Austrians, 15 Americans, and 7 others. Thomas evidently did not consider Italian music sufficiently serious or exalted for this series. The French, represented only by Saint-Saëns and Cherubini, fared little better. Among Americans, only John Knowles Paine found a place on any but the all-American concerts.

Most of the rest of the concerts on the Music Hall Series were choral concerts, but several included orchestral music. Here, Thomas sometimes chose lighter music, including two pieces by Karl Goldmark, one by Scottish composer Hamish MacCunn, and a harp solo by the orchestra's principal harpist, Edmund Schuecker. (Not that all orchestral music on the choral concerts was light: the June 24 concert paired the Brahms Requiem with Schumann's Fourth Symphony.)

Nearly all of the music on the symphonic concerts was written either by living composers or those who had been dead for no more than ten years. Thomas's programs are in this way, and in the excellent representation of American music, vastly different from the standard orchestral programs of today. Thomas's critics were quite right, however, when they protested the paucity of French music and the utter lack of Italian music. There was also too little music from northern and eastern Europe to fulfill the second of Thomas's guiding ideas.

Popular orchestral concerts

Thomas's attitude toward light music was one more of tolerance than approval. The frontispiece of his autobiography contains this assessment: "Light music, 'popular' so called, is the sensual side of the art and has more or less devil in it." His popular concerts at the fair differed from the symphonic concerts mainly by excluding complete symphonies and concertos. While there were plenty of dances and overtures, there were none of the arrangements of popular tunes or flashy virtuoso display pieces that were such an important part of the repertoire of the bands on the fairgrounds or, for that matter, such modern orchestras as the Boston Pops. Rossiter Johnson, in his official history of the fair, observed, "These concerts were to consist of music in a lighter and more popular vein, but still of a high character."5 By all accounts (except the Herald's second critic), the popular concerts were well attended.

Thomas presented 59 popular concerts, which featured the music of 22 German or Austrian composers and 39 composers of other nationalities. The largest number of these others were French and Americans. Wagner, with 51 performances, was the most frequently heard composer, followed by Dvořák (29), Johann Strauss, Jr. (29), Weber (22), Tchaikovsky (20), Saint-Saëns (20), J.S. Bach (17), Beethoven (17), Brahms (16), and Massenet (16). The lack of Italian music on the popular concerts seems especially inexcusable. Thomas programmed music by Rossini three times, Nicolai twice, and Leoncavallo once. Not even Verdi got a hearing in Jackson Park under Thomas's leadership!

After Thomas resigned, the orchestra continued to play for about three weeks. During the first week, it was divided into two parts and conducted by Max Bendix, the orchestra's concertmaster, and W. Dietrich. For two more weeks, a united orchestra played under Bendix. These concerts, operated as a concession with a 25¢ ticket price, do not appear in the official compendium of world's fair music programs. I found 35 programs in newspapers. They include music of 55 composers: 17 Germans or Austrians, 14 French, 6 Italians, and only 2 Americans. The most frequently performed composers were Strauss (31), Wagner (19), Weber (10), Dvořák (9), and Saint-Saëns (9). The leading Italian composers were Mascagni (4) and Rossini (3).

Bendix added soloists for the final week of orchestra concerts (September 2-7). Most strikingly important was soprano Louise Nikita, who performed on five of the nine concerts given during this time. She was a sensational success, drawing larger audiences than any other vocalist. And, at last, Verdi's music appeared on two of the programs. Even the Herald's critic finally found good things to say about the orchestra concerts. But then the orchestra disbanded for lack of funds. Bendix continued to organize popular concerts, but these consisted merely of a string quartet, piano, and vocal soloist, and attracted no critical attention.

Festivals, with chorus, orchestra, and eminent soloists

Choral director William L. Tomlins led three performances of Handel's Messiah and one each of Creation (Haydn), Elijah (Mendelssohn), St. Matthew Passion (Bach), Requiem (Brahms), and Stabat mater (Rossini). Other choral programs consisted of shorter works including, on one concert, music from the fifteenth century. Several concerts featured a 1200-voice children's chorus. All of these concerts were accompanied by the Exposition Orchestra while Thomas was on the job. After he resigned, a few choral concerts were given with piano accompaniment. But without the orchestra, the choral concerts, too, had to be abandoned. Nearly two dozen soloists performed with the chorus, including Emma Juch and Lillian Nordica. Most performed only one concert, but baritone George Ellsworth Holmes appeared on four concerts and English tenor Edward Lloyd on five. (Lloyd was also the featured soloist on the ballad concert.) Like the symphonic concerts, the choral concerts were well performed, but, on the whole, not well attended.

Tomlins was more flexible than Thomas and more sympathetic with popular taste. Late in June, apparently on a whim, he assembled the chorus for an outdoor concert of popular songs, in which audience participation was encouraged.6 For a couple of weeks afterwards, the chorus presented several concerts jointly with some of the bands. These concerts were popular, but they did not last long.

Concerts by famous visiting orchestras, bands, and choral societies from other cities

In the second week of May, the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the New York Symphony Orchestra performed two concerts each. The only other noteworthy American orchestra of the time, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, was also invited, but did not appear. Whether its conductor, Anton Seidl, declined the invitation or the orchestra was scheduled later in the year and was cancelled, I have not discovered.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra's conductor, Arthur Nikisch, had decided to return to Europe shortly before the fair, leaving it leaderless. Franz Kneisel, the concertmaster, conducted both concerts. Critics agreed that he had talent, but that his lack of conducting experience was painfully evident. Soloists with the Boston Symphony Orchestra were violinist Charles Martin Loeffler, cellist Alwin Schroeder, and soprano Felice Kachoska.

The New York Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Walter Damrosch, was even more disappointing. Critics found its intonation and ensemble not up to standard. Damrosch's performance must have been an embarrassment to Thomas's detractors, who had favored him to take over as music director in Thomas's place.7 Soloists with the New York Symphony Orchestra were violinist Adolph Brodsky and soprano Lillian Blauvelt.

Perhaps because there were more noteworthy choruses than orchestras, Tomlin's plans for guest ensembles were more ambitious than Thomas's. He invited choirs from all over the country to participate in a summer-long choral festival. Although he did not intend to have a formal competition, he did envision several choirs sharing concerts, giving the audience a chance to compare the state of choral singing in different cities.8 The meager response to his invitation meant that only two such concerts were ever given. Combining guest choirs into a large choir proved more successful. On successive days in June, one such combination performed the following pairs of works: Utrecht jubilate (Handel) and St. Paul, Part I (Mendelssohn), A Stronghold Sure (Bach) and selections from Lohengrin (Wagner), and selections from both Judas Maccabaeus (Handel) and Requiem (Berlioz). A different combination of choirs repeated this same sequence in July, and Upton wrote at length about the music societies that sang at the fair.9

The Lineff Russian Choir was engaged for the first week of June, emphasizing native folk songs and dances. The concerts also included Russian orchestral music, played by the Exposition Orchestra conducted by Votech Hlavec, conductor of the Russian Imperial Orchestra. Eugenie Lineff, a fine singer in her own right, took pains to be authentic regarding performance practice, dance, and costume. By contrast, most other Russian dancers seen in the West were influenced by the French school of ballet and other non-Russian culture. The six concerts they were hired to perform were so successful that two more were given the following week.10 After a summer-long tour of the United States, the chorus returned in October with an authentic representation of a Russian peasant wedding.

The Cymrodorian Society of Chicago, a Welsh literary and musical organization, sponsored an eisteddfod (a traditional Welsh competition in vocal music and poetry) in September. Tomlins served as one of the judges, but had no part in planning it. According to press coverage, the eisteddfod tradition dated back to the days of the Druids, who got the idea from the Greek Olympics. Alas, modern scholarship has determined that most of the colorful lore surrounding the eisteddfod was a late eighteenth-century hoax. The Chicago eisteddfod, the first ever held outside Britain, was authorized by the Welsh Arch-Druid, who sent his chief bard to officiate. It featured 9 men's choruses, 3 women's choruses, 4 mixed choruses, numerous soloists and small ensembles, and offered $30,000 in prize money. The Scranton Choral Union won first prize ($5,000) in the mixed choir competition, and the already famous Mormon Tabernacle Choir won second prize ($1,000).

Concerts by famous European or American artists and composers exhibiting their own works

No other category of music was so devastated by Thomas's resignation and cancellation of contracts as this one. Ignace Paderewski appeared on the very first concerts in May playing, among other things, his own concerto. In June, Arthur Foote conducted one of his orchestral pieces and played piano for one of his chamber works. Arthur Whiting played in one of his pieces on the same chamber concert. On August 12, the day Thomas's resignation became effective, Antonin Dvořák conducted three of his compositions. The Herald gleefully reported that the bureau of music had nothing to do with the concert.11 Considering that Dvořák was spending the summer in Iowa, and was thus the nearest of great composers, it seems like a curious omission, if the report is true.

When Thomas resigned, many contracts were cancelled in order to save money. Had his plans been fulfilled, conductors Hans Richter and Arthur Nikisch, and composers Alexander Mackenzie, Jules Massenet, and Camille Saint-Saëns would have appeared in the later months of the fair.12 The only noteworthy guest artist to arrive after Thomas left was French organist Alexandre Guilmant, who presented three recitals in September.

Open air band concerts

By far the most popular musical events at the fair were the open air band concerts. Many bands played at the fair, but none attracted more enthusiasm than that of John Philip Sousa. If the Herald can be believed, he attracted more people to each concert than the other bands combined drew in a week. That he invited the audience to sing along with some of the numbers at least partly explains his success. Sousa introduced this innovation at Tomlin's suggestion.13 The Herald was outraged when, after six weeks, Sousa left to fulfill other contractual obligations. Thomas, said the paper, was jealous of the band's success, did not want to share the glory, and did not realize what an asset Sousa was to the fair. (The fact is that Thomas had offered Sousa a contract for the entire summer, but his agent had already made other bookings. If the Herald's critic had read the interview with Sousa in his own paper,14 he could have spared his readers weeks of ill-mannered, uninformed complaints.)

The contrast between Sousa's approach to music and Thomas's is striking. While Thomas regarded himself as an educator, Sousa saw his role as an entertainer. Thomas sought to guide the public's taste, Sousa to anticipate it. Thomas disliked encores, believing that they detracted from the integrity of the programs he crafted so carefully. Sousa played at least two encores after each piece on the printed program.15 Nonetheless, the two men had tremendous respect for each other.

Although Sousa's was the most prominent—and historically most important—band at the fair, it was by no means the only one. In the opening months, two other bands shared the bandstands: Michael Brand's Cincinnati band and Adolph Liesegang's Chicago band. Of the three, the critic for Harper's Weekly liked the Cincinnati band the best.16 Not so the Herald's. After Sousa's departure, he constantly complained that the remaining bands were "dreary and perfunctory" and couldn't attract audiences.

After Thomas's resignation, the number of bands increased. Among the earliest of the new bands to hit the bandstands was the Iowa State Band led by Frederick Phinney. Actually, this band had been at the fair all summer, playing in various buildings in Jackson Park and on the Midway. What remained of Patrick Gilmore's band played a short engagement led by D.W. Reeves. A band from Elgin, Illinois, led by J. Hecker was, according to the Herald, the only band after Sousa's departure that drew crowds. It played at the fair from the latter part of August until the fair closed. During the last two weeks of the fair, Frederick Neal Innes, the foremost trombone soloist of his generation, brought his band. Numerous other bands performed at various times and places on the fairgrounds.

Chamber concerts

Chamber music appears to be the stepchild of the fair's music. There was very little of it, and the most important event came early. Franz Kneisel, concertmaster and temporary conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, remained for a week after the orchestra's concerts with his string quartet. His chamber concerts were as much of a critical success as his conducting had been a disappointment.

Two concerts, presented as the "American Artists' Series," were piano recitals by Kate Ockleston-Lippa and Neally Stevens. A few song recitals advertised in September, which were not included in the official compendium of programs, and the performances by Bendix's quartet constitute the only other professional chamber music.

Amateur concerts

Amateur concerts were given regularly in the Woman's Building and in some of the state pavilions. Unless they were especially well attended or had some unusual feature, they received scant attention in the press. For example, a concert by the Carlisle Indian band and choir merited attention largely because of the performers' race. When it was reviewed the next day, the speeches received more space than the music.17

The daily marimba quartet concerts in the Guatemala building were also suitably unusual. The marimba was not then a familiar instrument in this country. People found its sound—and the sight of four people playing it at once—fascinating. The Herald ran two fairly long articles about the instrument and its players: a shoemaker, a tailor, and two blacksmiths "who do not know the difference between a semi-quaver and the inscriptions on an Egyptian obelisk."18 Although they did not read music, they had good ears and soon played (in addition to their native music) such popular tunes as "After the Ball" and "The Bowery." Their instrument was not quite the same as the modern marimba. It had only one row of wooden bars, not two, corresponding to the white notes on a piano. In order to produce sharps and flats, the players placed bits of wax under some of the bars.19

Organ recitals

The sixty-stop organ in Festival Hall was one of the exhibits. More than sixty recitals were given on it, including three by French organist Alexandre Guilmant. Thomas's role in the organ concerts is not clear. On the one hand, he sought to avoid any connection with the commercial exhibits and, shortly before his resignation, cancelled all remaining contracts. On the other hand, the official compendium includes all of the organ recitals, which means that the programs were submitted to the bureau of music. Nearly all took place after Thomas's departure.

Although the organ was supposed to be ready for the opening of the fair, its dedication was delayed several times. An inaugural concert by eminent Chicago organist Clarence Eddy was announced for July 6, but the organ still was not ready. As the bickering over Thomas's handling of the music bureau rushed toward its final catastrophe, some feared that the organ would be finished only in time to sit in silence for the rest of the fair.

Eddy finally played the first concert on July 31. The organ featured an electric keyboard and an echo organ. One of the superintendents of construction bragged that "the organist might as well be in New York" because of the keyboard.20 The echo feature enabled Eddy to win a mock battle with Thomas the day after the first concert. Both wanted to rehearse in Festival Hall, so they tried to drown each other out. The orchestra could cover the main divisions of the organ, but was no match when Eddy started playing the echo as well.

Of all the organ recitals, Guilmant's attracted the most attention in the press and the largest audiences. The highlight of his first recital was his improvisation on "The Star Spangled Banner," which he had never heard before. But even over a month after the dedication of the organ, the recital was interrupted three times because of the instrument's misbehaviour.21 Guilmant's second concert was marred by latecomers finding their seats during the first number. The Herald's critic, of all people, lamented that Thomas's policy of not admitting latecomers to the hall except between pieces had been abandoned when he resigned.22

New Music

Although Thomas did not mention new music in his eight-point plan, he commissioned several works. At the dedication ceremony (October 22, 1892), John Knowles Paine's "Columbus March and Hymn" and George Whitefield Chadwick's "Dedicatory Ode" were premiered. Paine's piece required not only chorus and orchestra, but also military band. It was performed by a chorus of 5,500, an orchestra of 200, and Sousa's band, playing one of its first engagements.

Paine's March was repeated on the opening day of the fair (May 1, 1893) and again later in the summer. On May 2, for the dedication of the Women's Building, Thomas presented three new works by woman composers: "Grand March" by Jean Ingeborg von Bronsart of Weimar, "Dramatic Overture" by Frances Ellecott of London, and "Jubilate," a cantata by Mrs. H.H.A. Beach of Boston.

The bureau of music invited American composers to send new music for possible performance. Thomas selected three pieces for the August 4 Music Hall Series concert: "Overture: Witichis" by Margaret Ruthven-Lang, "Suite Creole" by John A. Broekhoven, and "Concert Overture" by Hermann Wetzler. Three other pieces were also identified in the compendium as being premieres: "World's Fair Waltz" by Koerting (July 1 popular concert), "Carnival Overture" by Harry Rowe Shelley (July 7 Music Hall Series concert), and "Suite: The Ruined Castle," also by Shelley (July 19 popular concert).

Not all of the new music was composed or premiered at the initiative of the music bureau. The Russian concerts in June featured "Triumphal March" by Alexander Glazunov, which included tunes from "Marching through Georgia" and "John Brown's Body." C.M. Ziehrer, leader of one of the Austrian bands on the Midway, composed "Columbian March" for the Fourth of July celebration and dedicated it to President Cleveland. The Iowa State Band performed a piece by Dalbey called "Twenty Minutes on the Midway." Perhaps other band music was written for the fair as well. Several organists and pianist Kate Ockleston-Lippa performed their own compositions, some of which may have been written for the fair.

Souvenir counters featured several piano pieces and songs, many with attractive pictorial covers. Some, like the song quoted at the beginning of this article, were published well before the fair opened and appear to have been intended as advertisements. (The World's Columbian Exposition was the first world's fair to have a special publicity department.23 Although I have found no hard evidence, it is possible that the department had something to do with the earliest souvenir music.) Other souvenir pieces bore the names of special features of the fair. Among the holdings of the Chicago Historical Society are "An Afternoon at the Midway Plaisance," "Cairo Street Waltz," and "Ferris Wheel Waltz." The Society has no music dedicated to any of the exhibit buildings in Jackson Park, but since earlier fairs had such pieces, there is no reason to suppose that the World's Columbian Exposition did not. Another class of souvenir music was named for special events, for example, "Chicago Day Waltz" or "The Viking March," which commemorated the arrival of Viking ships from Norway. There are also two songs about a fatal fire that claimed the lives of seventeen fire fighters.

Although I have touched on all of the most important music making at Jackson Park, much more happened. There was a music congress, a folk music congress that featured both live and recorded music, music for entertainment at any number of banquets and conventions, festival days for states and nations, music in the exhibit buildings, numerous dedication ceremonies, and Sunday morning worship services. Probably no other six-month period in American history featured so much music. But as diverse as the music making was in Jackson Park, the Midway Plaisance was a whole different world.

Music on the Midway

The official exhibit catalog of the Midway lists forty-nine exhibits, of which twenty regularly featured music, including restaurants with musical entertainment. Perhaps the best summary of music on the Midway opens the article on world's fair music in Harper's fair music in Harper's Weekly:

It is well for the pilgrim to the World's Fair if he have music in his soul and be moved with concord of sweet sounds. Not that even so the fair is a bed of roses, for there is most awful cacophony to be heard upon the Midway Plaisance. There are two or three authentic and awful bagpipers caterwauling attention to one of the side-shows, to wit, the 'World's Congress of Beauty.' Then there are a Turkish orchestra and an Egyptian orchestra and an Algerian orchestra, all of the same model, comprising a giant mandolin and a violin played like a cello, and drums beaten by hand. Yea, there is a Chinese orchestra; nay, there are two Chinese orchestras—one in the theatre, and one outside calling attention to the performance—and each more terrible than the other. These are in Ercle's vein. The Javanese orchestra is more condoling, consisting of mild flutes and an assortment of, as it were, zithers, and a large, so to speak, violin; but they are all soft and inoffensive instruments. All the same, the lover of what the civilized modern man means by music will get little good out of the barbarous bands.

What he will delight in is the civilized music. There are two bands in the German village, the same bands that were heard in New York, and these are presumably of the average, though certainly they are not the pick of German military bands. They discourse music which is a very good accompaniment to the refection one finds in the German village, and which is sometimes worth a more attentive listening. In 'Old Vienna' there is a good orchestra—a very good orchestra from the beer-garden point of view, which is also that of Old Vienna. There is an Italian band in one of the restaurants which contains a rather remarkable boy fiddler; and the Hungarian orchestra, erstwhile at the Eden Musée, may be heard at another restaurant. In fact, the music of the Midway is like the regimental bands of England as set forth by Mr. Rudyard Kipling:

'You can't get away from the tune that they play,'

and after a time this becomes a bore, no matter how good the tune may be. But this music is an 'incidental divertissement' to the catchpenny shows of the concessionaires.24

If the "civilized music" on the Midway bored even one who could not appreciate anything else, there seems little point in saying much about it. But the Herald's description of the dedication of the Ferris Wheel begs to be included. The Iowa State band was scheduled to play music not next to the Ferris Wheel, but inside one of the gondolas:

It was with many misgivings that the bewhiskered leader got his men into the car. But once seated the men started to play a rollicking march. Then of a sudden the wheel began to revolve.

As the car ascended the man with the clarionet glared wildly out the window and laid his instrument upon the seat. Then the alto horn dropped out as the ground began to drop from beneath the players' feet. As the car climbed to a greater altitude other horns and fifes withdrew their support from the leader, who wasn't looking any too well himself. At the top of the wheel it seemed as though the march, which had been started with so much gusto a few moments before, had dwindled to the exertions of the bass drum and the piccolo.25

Nine different villages featured non-Western music: South Sea Islands Village, Java Village, Turkish Village, Street in Cairo, Persian Palace, Algerian and Tunisian Village, East India Bazaar, Chinese Village, and Dahomey Village. Too often, writers used this music merely as a source of cheap laughs. At least one critic was offended by the smirking of his colleagues:

A clever writer for a daily paper has done what we have all meant to do 'when we got time,' and that is write a column or two about the music of the Midway. For it deserves some notice, this queer, droning, shrieking clamor, now loud now soft, now emitting screams like a calliope, which is incessant upon that motley thoroughfare known by a name which will awaken those dins in our ears, for years to come, by thinking on it. The writer of the article in question does not become too technical to be interesting. He calls the Syrian song 'a croak' and the Chinese orchestral performance 'crystalized malice.' This is not the language of the professional humorist nor yet of the critic. That is to say, there is a system about the malice and the croak is not accidental. And just as analyzing a toothache will sometimes help to bear the pain, it might be alleviation to study the workings of the Chinese scale and the formation of its gamut . . .

But what we want is not a funny article in which adjectives and nouns are lugged in to amuse, but a learned disquisition on barbaric musical systems. These exist in books; but we want a live modern musician to describe those queer modes and intervals and chromatics. We all know what the shrieks sound like; what do the shrieks mean! It might help us to bear them better if we were told.26

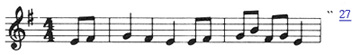

Since so few contemporary observers could write adequately and fairly about non-Western music, I will confine my comments to three villages. The Algerian and Tunisian Village featured some of the belly dancers that made the fair so notorious. They were accompanied by the so-called "hootchy-kootchy" tune. It was not a legitimate Arabian melody, however. It was composed for the occasion by Sol Bloom, the concessionnaire of the village. He later bragged, "Hardly a grandfather is now alive who won't remember my piece. It goes like this:

Anyone who was suspicious about the authenticity of the Algerian Village must have found the Javanese Village a refreshing change. Harper's Weekly observed:

But the Javanese really give one a sense of learning something. The village one perceives at once to be a transplantation of an actual section of 'the most Eastern East' with all its indigenous manners and customs . . .

Perhaps that is . . . the chief charm of the Javanese village, that the people do not seem to be got up for show purposes, but to be going tranquilly about their own daily business as if they were at home.28

While most of the rest of the Oriental music seemed loud and strident, Javanese music was quiet and soothing, and for that reason, received very good press. Harper's Weekly even admitted, "Their flutes . . . are really musical instruments."29

Dahomey Village, on the other hand, seemed both to attract and repel by its very savagery. The Midway catalog shows that American ignorance of geography is no recent phenomenon: "The Dahomey Village of thirty native houses has a population of sixty-nine people, twenty-one of them being Amazon warriors." It would be tiresome to repeat the smug and smirking comments in the newspapers. Fortunately, Henry Edward Krehbiel left an excellent description:

I listened repeatedly during several days to the singing of a Dahoman minstrel. . . . All day long he sat beside his little hut, a spear thrust in the ground by his side, and sang little descending melodies in a faint high voice. . . . To his gentle singing he strummed an unvarying accompaniment upon a tiny harp. . . . With his right hand he played over and over again a descending passage of dotted crotchets and quavers in thirds; with his left hand he syncopated ingeniously on the two highest strings.

A more striking demonstration of the musical capacity of the Dahomans was made in the war-dances which they performed several times every forenoon and afternoon. These dances were accompanied by choral song and the rhythmical and harmonious beating of drums and bells, the song being in unison. . . . The fundamental effect was a combination of double and triple time, the former kept by the singers, the latter by the drummers, but it is impossible to convey the idea of the wealth of detail achieved by the drummers by means of exchange of the rhythms, syncopation of both simultaneously, and dynamic devices. . . . I was forced to the conclusion that in their command of the element, which in the musical art of the ancient Greeks stood higher than either melody or harmony, the best composers of today were the veriest of tyros compared with these black savages.30

The popularity of the Dahomey Village is often mentioned as one of the factors in the growth of ragtime. The same racism that kept so many people from appreciating non-Western music on the Midway nearly obliterates any possibility of ever knowing the origins of ragtime. But while it is impossible to prove it, it is difficult to doubt the statement that "The general public first heard ragtime on the Chicago Midway, but its catchy name had yet to be found."31

Itinerant pianists from all over the central United States had been travelling from town to town and fair to fair for years, competing informally. Naturally, many, both black and white, flocked to Chicago for the world's fair. Among them were Scott Joplin, Otis Saunders, Johnny Seymour, and Ben Harney, all of whom became prominent in the ragtime movement. They played not only on the Midway, but also in Chicago's red light district.32

Given the unsavory surroundings of much of their activities, it is understandable that the official history of the fair and the press took no notice of them. But by the end of the century, ragtime was one of the dominant forces in American popular music. If there is no positive proof that the World's Columbian Exposition was the birthplace of ragtime, there is at least a good enough circumstantial case that no other theory has gained a significant following. And so even if none of the musical events in Jackson Park had taken place, the World's Columbian Exposition would still rank as one of the more important events in the history of American music.

1George Upton, ed., Theodore Thomas: A Musical Autobiography, 2 vols. (Chicago: McClurg, 1905), I:194-195.

2For more information about this controversy, see Paul and Ruth Hume, "The Great Piano War," American Heritage 21 (October 1970): 16-21.

3Charles Edward Russell, The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1970), p. 229.

4Upton, I:195.

5Rossiter Johnson, A History of the World's Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, 4 vols. (New York: Appleton, 1897-98), I:468.

6Chicago Herald, June 28, 1893.

7Chicago Herald, May 20, 1893.

8Johnson, I:469.

9George Upton, "Musical Societies of the United States and Their Representation at the World's Fair," Scribner's Magazine 14 (July 1893): 68-83.

10Chicago Herald, June 11, 1893.

11Chicago Herald, August 6, 1893.

12Russell, p. 234; Philo Adams Otis, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: Its Organization, Growth and Development, 1891-1924 (Chicago: Summy, 1924), p. 50.

13Harry W. Schwartz, Bands of America (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1957), p. 158.

14Chicago Herald, June 27, 1893.

15Paul E. Bierley, John Philip Sousa, American Phenomenon (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1973), p. 139.

16"Music at the Fair," Harper's Weekly 37 (August 5, 1893): 742.

17Chicago Herald, October 3, 4, 1893.

18Chicago Herald, August 11, 1893.

19Chicago Herald, September 11, 1893.

20Chicago Daily News, August 1, 1893.

21Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1893.

22Chicago Herald, September 2, 1893.

23Julian Ralph, Harper's Chicago and the World's Fair (New York: Harper, 1893), p. 127.

24"Music at the Fair," 741.

25Chicago Herald, June 22, 1893.

26Chicago Evening Post, July 30, 1893.

27Sol Bloom, The Autobiography of Sol Bloom (New York: Putnam, 1948), p. 135.

28"The Javanese Village," Harper's Weekly 37 (October 21, 1893): 101.

29Ibid.

30Henry Edward Krehbiel, Afro-American Folk Songs: A Study in Racial and National Music (1914, reprinted New York: Ungar, 1962), pp. 60, 64-65.

31Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, They All Played Ragtime: The True Story of an American Music (New York: Knopf, 1950), p. 4.

32Ibid., p. 41.