Traditional Italian tempo indications (tempo terminology) create great uncertainty for the performer, and contemporary performance practice bears witness to this problem. One can hear different artists play the same composition at various tempi, and evidently, each of them sincerely believes he correctly understands the tempo direction of the composer. Discrepancies in tempo are usually justified on the basis that a composer perceives the speed of a composition in a rather broad area, and gives the performer permission to choose within that zone. This approach would seem to be confirmed by the presence of a range for each tempo term (adagio, andante, allegro, etc.) on the scale of the metronome. If this were true, composers would have indicated zones with their metronome markings; however, composers, as a rule, use precise metronome markings.1 The discrepancy between vague verbal tempo indications and the precision of metronome markings constitutes the basic problem of tempo.

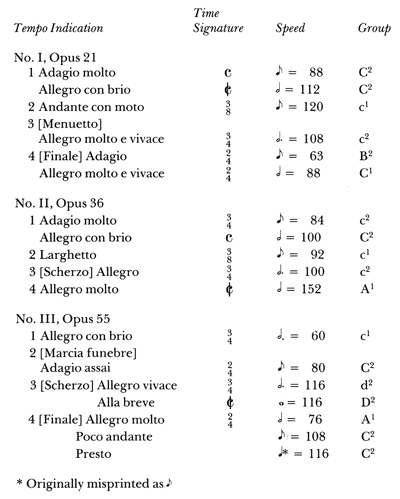

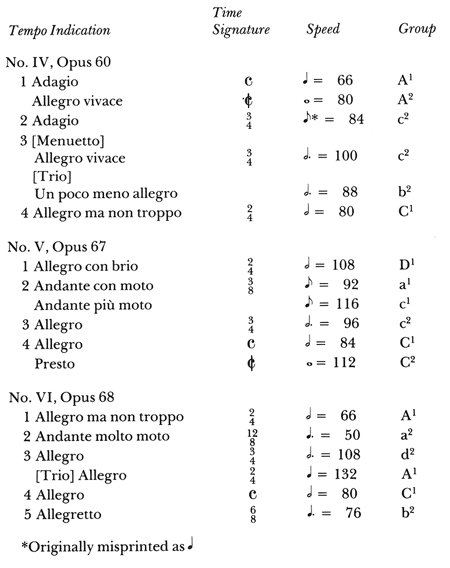

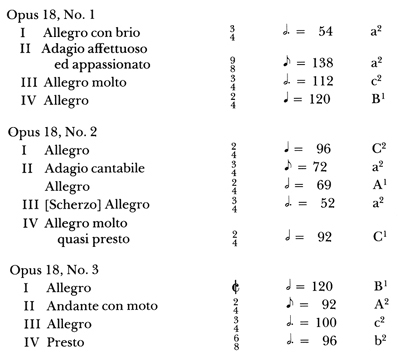

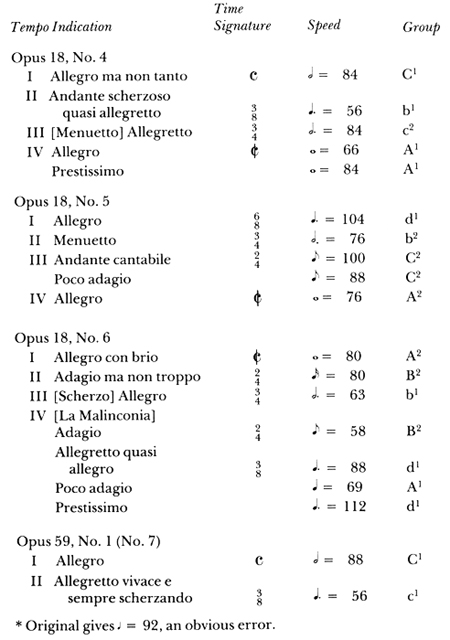

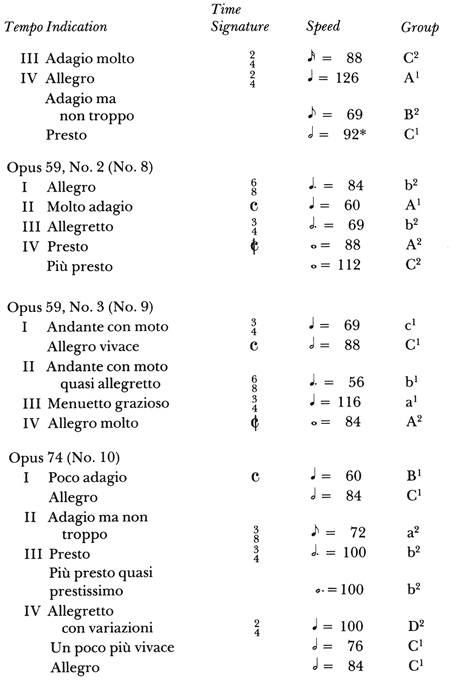

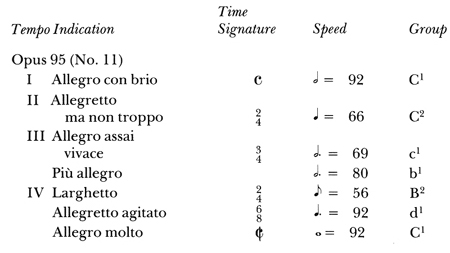

Contrary to the "zone idea," tempo terminology presupposes direct step-by-step progression: a faster tempo indication should correspond to a higher speed in performance, and a slower indication to a lesser speed in performance; consequently, different pieces carrying the same tempo indication should have the same speed. At first glance, such a simple thought may seem naive and even absurd. Every musician knows that compositions bearing the same tempo indication often have quite different speeds. Composer's own metronome markings support this practice. For example, Beethoven's metronome markings for "allegro" range from 52 to 144, and for "adagio" from 56 to 138 (see Table 1). Of course, this range can be narrowed by using only compositions which have metronome markings given in the same note value (time unit). Even then, the zone for each tempo is quite broad. If tempo indications have such a wide range of speed, and the goal of a composer is only to define the general character of a movement, the tempo terminology as a means of communication between composer and performer becomes unnecessary. For instance, in J.S. Bach's music, where tempo indications are given only in exceptional cases, a performer, taking as a basis the character of the music, its genre, and its structural peculiarities, can define the tempo without confusing a slow movement with a fast one.2 Obviously, the tempo indication requires a precise definition of the speed of a composition that is reflected in the precision of the metronome marking (i.e. "allegro,"  = 132, but not

= 132, but not  = 126-144). All this makes the notion of "correct tempo" especially significant.

= 126-144). All this makes the notion of "correct tempo" especially significant.

Composers have often emphasized the importance of correct tempo. Mozart, in a letter to his father dated October 24, 1777, names tempo as "the most essential, the most difficult, and the chief requisite in music."3 Beethoven received the invention of the metronome with great enthusiasm. In his opinion, it gave the composer the means of defining his intended tempo with utmost accuracy. He prepared a list of tempi in accordance with Maelzel's metronome for all his symphonies, most of his quartets, and also for some other compositions, and he maintained his enthusiasm for the metronome to the end of his life. Wagner wrote in his article "On Conducting" that the correct tempo, by itself, gives the performer the means to the correct interpretation of the work. Stravinsky has indicated a similar opinion: "Tempo is the principal item. A piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo . . . I think that any musical composition must necessarily possess its unique tempo (pulsation): the variety of tempi comes from performers, who often are not very familiar with the composition."4 It is clear that if a piece can be performed in different tempi, the term "correct tempo" loses its meaning.

The definition of tempo in dictionaries also contradicts the "zone idea" of tempo. In Hugo Riemann's Musik Lexikon, tempo is defined as: "a measure of time; an indication which determines, for a given occasion, the absolute meaning of note values."5 Certainly, one has to consider the expression "exact tempo" as a relative concept, to the extent that it must cover the zone between neighboring figures on the metronome scale. The difference in speed within such limits is scarcely noticeable, and may be compared to the slight difference between a natural and a tempered semitone. In addition, the words "correct tempo'" usually imply the general tempo of a composition without consideration of the slight fluctuations which inevitably occur during performance. Subject to these considerations, "correct tempo" means the exact and only possible speed; however, we once more encounter the contradiction between the precision of metronome markings, and the vagueness of tempo terms. In order to overcome this contradiction, and to understand the purpose and character of tempo indications, it is reasonable to appeal to the composer himself; to consider the relationship of a composer's tempo indications and metronome markings.

The works of Beethoven, provided with his metronome markings, are extremely valuable for such an analysis. First, most of these works are symphonies and quartets which yield comparisons between different compositions because of their resemblance in form and genre.. Secondly, the variety of tempi within four-movement compositions broadens the field of research. Finally, the fact that Beethoven provided specific metronome markings for groups of his major compositions suggests that he was guided by definite principles, and probably by a comparative method.

A general survey of Beethoven's metronome markings (see Table 1), as mentioned in the beginning of this article, confirms the observations concerning the range of metronome markings for each tempo term. Moreover, at first glance, in the absence of any conformity between tempo indications and metronome markings, there arises the impression of such variety as to be almost chaotic. Such a simple arithmetical approach, however, is inappropriate. The material compared must not be chosen arbitrarily, but must include only examples containing similar features. In an attempt to characterize the specific conditions which will allow us to locate comparable material, the field of our research will be gradually narrowed.

One must consider that metronome markings are given notes of definite values, chosen to serve as pulsing time units. It would be nonsense to compare, for instance, different movements of String Quartet Op. 18/1. Although "allegro con brio" is indicated by MM 54, and "adagio" by MM 138, the former applies to a full measure, and the latter only to one eighth note. It is possible to compare only examples having identical time units, or at least those metronome markings which can be reduced to a common denominator (i.e.  = 132,—

= 132,—  = 66). Nonetheless, even for the same time units, there is still no conformity between tempo indications and metronome markings. Beethoven prefaced the first movement of the Fifth Symphony and the finale of the Seventh Symphony with "allegro con brio," and with the same time unit (a half note in duple time), but the metronome markings differ considerably (108 vs. 72 pulsations per minute). Evidently, we must consider other factors, and primarily the saturation of time units with notes of lesser value. In the first movement of the Fifth Symphony, we find there are eighth notes, but in the finale of the Seventh, sixteenth notes. No wonder a measure of the latter takes more time! Therefore, apart from the time signature and time unit, we must also consider the rhythmic pattern of the compositions compared. Even so, the comparison does not give satisfactory results. The next two examples vividly demonstrate that paradox of tempo terminology. The finale of the Eroica Symphony is marked "allegro molto,"

= 66). Nonetheless, even for the same time units, there is still no conformity between tempo indications and metronome markings. Beethoven prefaced the first movement of the Fifth Symphony and the finale of the Seventh Symphony with "allegro con brio," and with the same time unit (a half note in duple time), but the metronome markings differ considerably (108 vs. 72 pulsations per minute). Evidently, we must consider other factors, and primarily the saturation of time units with notes of lesser value. In the first movement of the Fifth Symphony, we find there are eighth notes, but in the finale of the Seventh, sixteenth notes. No wonder a measure of the latter takes more time! Therefore, apart from the time signature and time unit, we must also consider the rhythmic pattern of the compositions compared. Even so, the comparison does not give satisfactory results. The next two examples vividly demonstrate that paradox of tempo terminology. The finale of the Eroica Symphony is marked "allegro molto,"  = 76, but the finale of the Fourth Symphony "allegro ma non troppo,"

= 76, but the finale of the Fourth Symphony "allegro ma non troppo,"  = 80. It seems strange that the indication cautioning "not too fast" should require a greater speed than "very fast" by virtue of their metronome indications. There are other examples: the finale of the Fifth Symphony, marked "allegro,"

= 80. It seems strange that the indication cautioning "not too fast" should require a greater speed than "very fast" by virtue of their metronome indications. There are other examples: the finale of the Fifth Symphony, marked "allegro,"  = 84, and the finale of the Ninth Symphony, marked "allegro assai,"

= 84, and the finale of the Ninth Symphony, marked "allegro assai,"  = 80.

= 80.

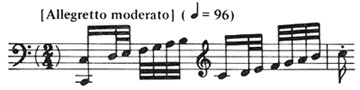

So far we have investigated only the quantitative side of this phenomenon without touching upon the qualitative side. It is logical to suppose that the speed of a given note value (time unit) is influenced not only by the density of notes of lesser value, but also by their structural character. As experimental material, three of Beethoven's piano compositions are chosen: the finale of the Waldstein Sonata; the first movement of Sonata Op. 10, No. 2; and the first movement of Sonata Op. 14, No. 2. In the first two examples, the speeds are apparently quite close, or even the same, but the tempo indications are completely different ("allegretto moderato" and "allegro," respectively). If we compare the first movements of Op. 10/2 and Op. 14/2, the speed of the latter ought to be considerably less, although "allegro" is indicated for both.6 These apparent contradictions can be resolved by examining the figurations in all three movements. A comparison of passages of thirty-second notes in the three movements reveals their different structures: in the finale of the Waldstein sonata, the passages are scales of the glissando type; in Op. 10/2, the passages have a subordinate, but nonetheless appreciable, function—taking part in the variation of one of the principal themes; and finally, in Op. 14/2, the thirty-second notes constitute a quite complicated melodic outline.

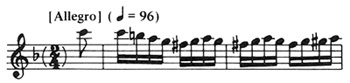

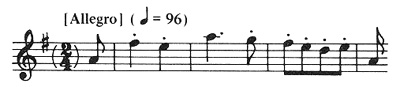

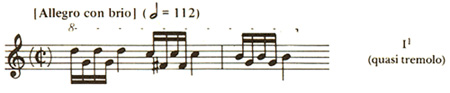

Example 17

a. Sonata Opus 53, 1st Movement, measure 55.

b. Sonata Opus 10, No. 2, 1st Movement, measure 43.

c. Sonata Opus 14, No. 2, 1st Movement, measure 41.

Here we have three types of figuration. It is apparent that each example requires a different level of distinctness from the performer, and also a different degree of attention to detail from the listener. Therefore, the speed chosen for examples (a) and (b) should be valued differently from a psychological point of view. For the quasi-glissando passage, the tempo indication is not fast ("allegretto moderato"), but for the figuration of harmonic structures with a more melodic content the same metronome marking results in a faster tempo indication ("allegro"). In the last example the wavy outline of the passage requires more time, and therefore, its slower speed is designated "allegro" as well.

Similar correlations are not difficult to find on a larger scale of note values. The sixteenth notes in the finale of the Waldstein Sonata are used in recurring, so-called general forms of passage work, widely used in instructive studies. The more melodic significance of the passages with the same note values in Op. 10/2 is evident. In Op. 14/2, the composer uses the sixteenth notes to set forth the principal theme, which distinguishes itself by notable outline.

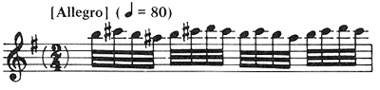

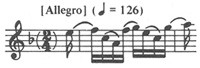

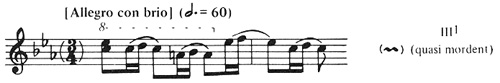

Example 2

a. Sonata Opus 53, 1st Movement, measure 27.

b. Sonata Opus 10, No. 2, 1st Movement, measure 37.

c. Sonata Opus 14, No. 2, 1st Movement, measure 1.

In examples (a) and (b) the same speed is once more indicated differently: only moderately animated ("allegro moderato") for the etude-like sixteenths of the Waldstein Sonata and a rather fast ("allegro") for the melodic line of Op. 10/2. Again, the same "allegro" in Op. 14/2 will require a more moderate speed in view of its greater melodic content, and the comparatively large intervals of the theme. Thus, the same speed for the same note value bears different tempo indications, depending on melodic content. Similarly, structural distinctions in the melodic line account for different speeds in compositions which have the same tempo indication. This is the author's foundation for a classified system of Beethoven's metronome markings.

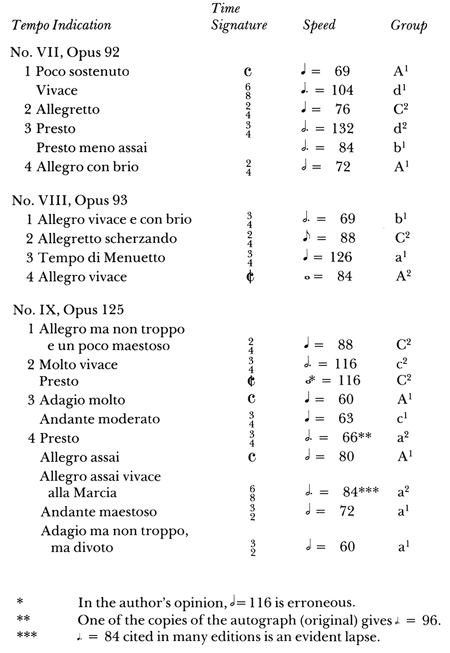

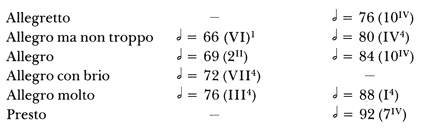

Herein follows a tabulated classification of Beethoven's metronome markings for several fast movements of symphonies and quartets.8 All examples in each category have a similar figuration. The time signature is in each case  , the time unit

, the time unit  (i.e. a whole bar). Table 2a shows the extremes of metronome markings corresponding to various tempo categories.9 The closeness of the figures in each column is very noticeable. A change of speed by only one numeral on the scale of the metronome results, in each case, in a new tempo indication. This means that the conductor who interprets, for instance, the first movement of the Pastoral Symphony at a speed of 69 bars to the minute, instead of Beethoven's indication of 66, raises the tempo to "allegro," consequently neglecting the composer's "ma non troppo."

(i.e. a whole bar). Table 2a shows the extremes of metronome markings corresponding to various tempo categories.9 The closeness of the figures in each column is very noticeable. A change of speed by only one numeral on the scale of the metronome results, in each case, in a new tempo indication. This means that the conductor who interprets, for instance, the first movement of the Pastoral Symphony at a speed of 69 bars to the minute, instead of Beethoven's indication of 66, raises the tempo to "allegro," consequently neglecting the composer's "ma non troppo."

Table 2a, naturally, does not include the entirety of Beethoven's metronome markings. The other markings are distributed in ranges close to those shown in the table. Variations are caused by differences in texture and rhythmic construction. In some cases, these deviations can be explained by the influence of the time signature, or of the value of the time unit. For instance, the middle section in the "Scherzo" of the Pastoral Symphony ("allegro") is indicated  = 132, and not 138 as it should have been in comparison with

= 132, and not 138 as it should have been in comparison with  = 69 (2II), because the more frequent accentuation within a bar overloads, and hence restrains, speed. Similarly, in comparison with the quadruple time signature, the ordinary measure of the duple time signature has a slightly lesser speed, because the additional bar line slows the flow of the music. That is the reason a short measure in the finale of the Eroica (

= 69 (2II), because the more frequent accentuation within a bar overloads, and hence restrains, speed. Similarly, in comparison with the quadruple time signature, the ordinary measure of the duple time signature has a slightly lesser speed, because the additional bar line slows the flow of the music. That is the reason a short measure in the finale of the Eroica ( = 76), for example, is one step slower than half a measure in the "Ode to Joy" of the Ninth Symphony (

= 76), for example, is one step slower than half a measure in the "Ode to Joy" of the Ninth Symphony ( = 80).

= 80).

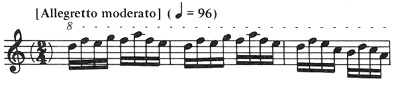

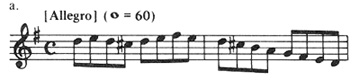

A more important factor is the rhythmic scale, which relates to the diminution of note values. Its influence on tempo is reflected in the following example.10

Example 3: Sonata Opus 14, No. 2, measure 43.

This principle can be applied to material in which notes of different value appear in similar melodic functions. A confirmation can be found in Beethoven's metronome markings for "allegro": V4 = 84—21

= 84—21 = 96.11

= 96.11

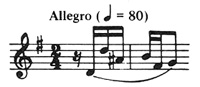

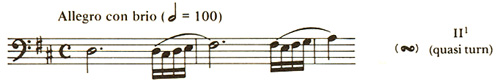

Example 4

a. Symphony No. 5, Opus 67, 4th Movement, measure 1.

b. Quartet Opus 18, No. 2, 1st Movement, measure 36.

The works in "alla breve" present a special phenomenon. The sign  points to the speed of the lesser rhythmic scale. Thus, representations (a) and (b) of Example 3, if written in

points to the speed of the lesser rhythmic scale. Thus, representations (a) and (b) of Example 3, if written in  , should have been marked

, should have been marked  = 69, and

= 69, and  = 80, respectively.12 In other cases, slight differences in speed in movements having the same tempo indication are influenced by details in articulation and texture. As an example, the "Trio" section of the "Scherzo" in the Pastoral Symphony is marked "allegro,"

= 80, respectively.12 In other cases, slight differences in speed in movements having the same tempo indication are influenced by details in articulation and texture. As an example, the "Trio" section of the "Scherzo" in the Pastoral Symphony is marked "allegro,"  = 132. The finale of the Seventh Quartet, Op. 59/1, is also marked "allegro," but only

= 132. The finale of the Seventh Quartet, Op. 59/1, is also marked "allegro," but only  = 126. This discrepancy can be explained by the number of slurs in the latter, which realization takes a certain amount of time.

= 126. This discrepancy can be explained by the number of slurs in the latter, which realization takes a certain amount of time.

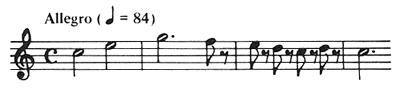

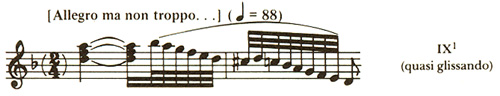

Example 5

a. Symphony No. 6, Opus 68, 3rd Movement, Trio, measure 1.

b. Quartet Opus 59, No. 1, 4th Movement, measure 38.

A comparison between the finale of the Fifth Symphony, and the "Storm" movement from the Pastoral Symphony ("allegro,"  = 84, and "allegro,"

= 84, and "allegro,"  = 80) shows that the difference in metronome markings is due to their different rhythmic densities. In the "Storm," the texture consists mainly of quintuplets which call for a slight slackening, while the finale of the Fifth Symphony contains ordinary sixteenth notes.

= 80) shows that the difference in metronome markings is due to their different rhythmic densities. In the "Storm," the texture consists mainly of quintuplets which call for a slight slackening, while the finale of the Fifth Symphony contains ordinary sixteenth notes.

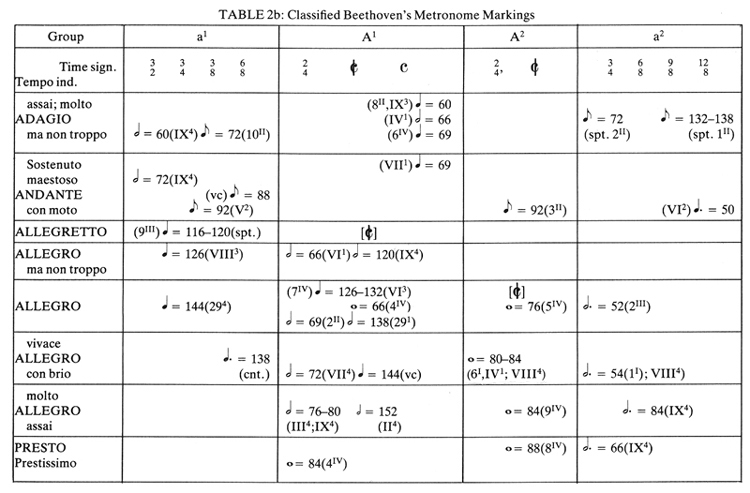

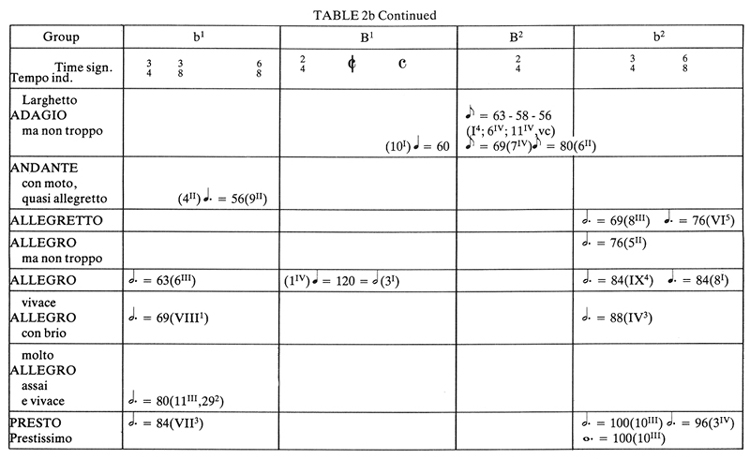

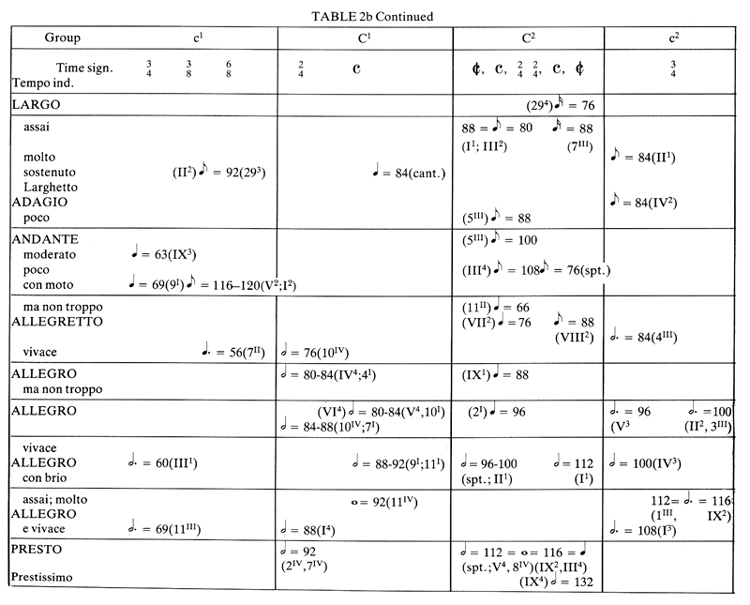

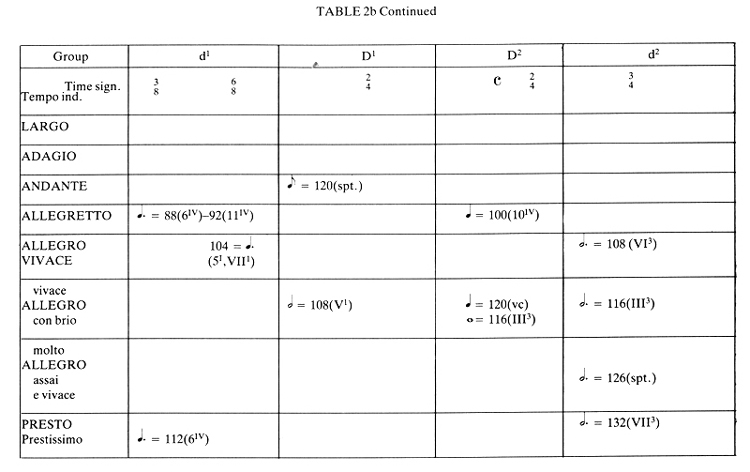

Using the aforementioned factors as a foundation, our main goal can now be achieved: to classify all of Beethoven's metronome markings of Table 1. Table 2b is compiled in a stepwise manner: the higher the tempo indication, the greater the speed, and vice versa. Accordingly, all tempo terms from "largo" to "prestissimo" are placed in order from top to bottom. The table is also divided across in four groups—A, B, C, D.

Each of these main groups is subdivided into four smaller groups, based on the differences of time signature and rhythmic scale. The groups marked by capital letters include examples of even time signatures. Numbers 1 and 2 refer to rhythmic scale differences. The groups marked by small letters contain examples of odd time signatures, including compound measures divisible by 3 ( ,

,  ). Their relationship with the neighboring columns of capital letters is based on the coincidence, closeness, or proportionateness of the metronome figures. Compare, for example, section of "allegro": C 2 - c2,

). Their relationship with the neighboring columns of capital letters is based on the coincidence, closeness, or proportionateness of the metronome figures. Compare, for example, section of "allegro": C 2 - c2,  = 96—

= 96— = 96; or A2 - a2,

= 96; or A2 - a2,  = 76 (

= 76 ( = 152)—

= 152)— = 52 (

= 52 ( = 156). Further division of subgroups reflects inner differentiations of both even and odd time signatures (

= 156). Further division of subgroups reflects inner differentiations of both even and odd time signatures ( ,

,  ,

,  or

or  ,

,  ,

,  ), distinction of time units or details of texture.

), distinction of time units or details of texture.

It is important for the reader to understand the relationship of Tables 1 and 2b. Beethoven's metronome markings can be found in either one. For convenience, each example in Table 1 is provided with both a tempo indication and a reference to the appropriate box in Table 2b, which is, in fact, a system of coordinates. The author believes that all of the contradictions and paradoxes of Beethoven's metronome markings mentioned above can be resolved within the framework of the Table.

There is a curious fact, stated earlier in this article, that Beethoven marked the finale of the Fourth Symphony "allegro ma non troppo,"  = 80, while the finale of the Eroica Symphony is marked "allegro molto,"

= 80, while the finale of the Eroica Symphony is marked "allegro molto,"  = 76. It is now understood that these examples are not comparable, since they belong to two different categories, specifically to groups C and A. This applies to two other examples mentioned earlier: V4, "allegro,"

= 76. It is now understood that these examples are not comparable, since they belong to two different categories, specifically to groups C and A. This applies to two other examples mentioned earlier: V4, "allegro,"  = 84—IX4, "allegro assai,"

= 84—IX4, "allegro assai,"  = 80.

= 80.

The next few examples corroborate this method of classification, especially its essential factor—the analysis of the melodic outline of figuration. Look at the more complicated design of the figuration taken from a composition (VII4), which belongs to group A. Quite often, it carries the theme itself.

Example 6: Symphony No. 7, Opus 92, 4th Movement, measure 5.

The melodic line, which requires clear delivery of each note, is naturally not expected to be performed very quickly, even though the tempo indication infers a high speed. On the other hand, in group C we come across less-individualized figurations, which resemble written-out ornamentations: glissando passages, sets of grace notes, mordents, turns, tremolos, etc. Such simple melodic lines do not require perception of distinct details, and can be played very quickly without creating the impression of an extremely fast tempo.

Example 7

a. Symphony No. 9, Opus 125, 1st Movement, measure 34.

b. Quartet Opus 18, No. 1, 1st Movement, measure 1.

c. Symphony No. 2, Opus 36, 1st Movement, measure 1.

d. Symphony No. 1, Opus 21, 1st Movement, measure 69.

e. Symphony No. 3, Opus 55, 1st Movement, measure 65.

Groups B and D include samples of texture variations. In group B there are examples in which the time units consist of more notes than in the examples of group A, and therefore, they are somewhat slower. On the contrary, group D contains samples of "thinned-out" texture, and speeds are, therefore, faster than in group C. Each group in this Table includes examples of a certain type, and the increase or decrease of speed in metronome figures may be traced by looking vertically at the Table.

By examining the Table horizontally, a discovery is made of the average level of speed for every type of figuration within the same tempo indication. Look at the ornamental type of passage texture in "allegro." In group C the time unit gives the average figure of 90 beats per minute ( = 84,

= 84,  = 96). To the extent that there are eight notes to the beat, there are 720 notes per minute (90 × 8). In those works wherein the same type of figuration is represented by triplets (B1), Beethoven gives a metronome marking of 120 for a semi-bar. Taking into account that a semi-bar has two triplets, the speed of the notes of smallest duration is the same (120 × 6 = 720). This demonstrates that "allegro" indicates equal speed for the smallest note values (even though differently grouped) on the average of 720 sounds per minute.

= 96). To the extent that there are eight notes to the beat, there are 720 notes per minute (90 × 8). In those works wherein the same type of figuration is represented by triplets (B1), Beethoven gives a metronome marking of 120 for a semi-bar. Taking into account that a semi-bar has two triplets, the speed of the notes of smallest duration is the same (120 × 6 = 720). This demonstrates that "allegro" indicates equal speed for the smallest note values (even though differently grouped) on the average of 720 sounds per minute.

Example 8

a. Quartet Opus 18, No. 2, 1st Movement, measure 1.

b. Quartet Opus 18, No. 1, 4th Movement, measure 1.

Consider the figuration of more complicated patterns. In group A, where the figuration is entrusted to sixteenth notes (eighth notes in  ) Beethoven gives a quarter in "allegro" 1/135 of a minute on the average (

) Beethoven gives a quarter in "allegro" 1/135 of a minute on the average ( = 132,

= 132,  = 69). Sixteenth notes will be played at the rate of 540 per minute (135 × 4). The average value for notes in triplets in group C coincides with this figure. Inasmuch as a unit consists of two triplets (90 × 6 = 540), the notes will be played at the same speed.

= 69). Sixteenth notes will be played at the rate of 540 per minute (135 × 4). The average value for notes in triplets in group C coincides with this figure. Inasmuch as a unit consists of two triplets (90 × 6 = 540), the notes will be played at the same speed.

Example 9

a. Quartet Opus 18, No. 2, 2nd Movement, Allegro, measure 1.

b. Symphony No. 5, Opus 67, 4th Movement, recapitulation, measure 48.

Movements with odd time signatures should be considered separately. Owing to more infrequent metrical accents, they are to be played at a somewhat greater speed in comparison with movements of even time signatures. Thus, the fugue of the Hammerklavier Sonata (in  ) has a metronome marking of

) has a metronome marking of  = 144, while the remaining movements in the A1 group in "allegro" are distributed in a range of 132 to 138. The same consideration applies even more to movements in which the time unit is a whole bar (2III,

= 144, while the remaining movements in the A1 group in "allegro" are distributed in a range of 132 to 138. The same consideration applies even more to movements in which the time unit is a whole bar (2III,  = 52, a2). Naturally, the speed of the sixteenth notes will also be faster: 52 × 12 = 624 notes per minute (12 notes to a bar). It should be noted that this speed is the same as the speed in "allegro" of the d1 group. There are 104 bars per minute, and therefore, 624 notes per minute (104 × 6 = 624).

= 52, a2). Naturally, the speed of the sixteenth notes will also be faster: 52 × 12 = 624 notes per minute (12 notes to a bar). It should be noted that this speed is the same as the speed in "allegro" of the d1 group. There are 104 bars per minute, and therefore, 624 notes per minute (104 × 6 = 624).

Conclusion: In different compositions the tempo indication "allegro" establishes a definite speed for each type of figuration (written in notes of different value), subject to insignificant deviations due to the influence of textural and rhythmic factors. The idea that the tempo indication (i.e. "allegro") may result in the same speed in different compositions, an idea which seemed to be nonsense at the onset of the article, now turns out to be valid. The foregoing analysis of the "allegro" movement is, of course, equally applicable to the other tempo indications, since tempo terminology is a graduated system. All of its contradictions prove to be imaginary, the result of metric/rhythmic peculiarities by which the time units of different compositions include different numbers of sounds per group (4, 6, 8). It is taken for granted that the duration of these pulsing units, if expressed in figures, turns out to be different.

The dependence of tempo on different factors may be expressed by the formula: v α  , where "v" is the speed of pulsation sought for the basic time unit (i.e. the metronome marking); "α" is a sign of proportion; "t" is the indication of tempo (term); "q" is the indicator of the melodic content of the rhythmic units which allows one to attribute the given example to any of the groups in the table; and "n" reflects the quantity of other elements which cause additional influence on tempo (rhythmic scale, time signature, articulation, textural details, etc.). According to this formula, the higher the tempo term, and the less saturated the melody and texture, the faster the speed of performance and vice versa. The correlation between "t" and "qn," with the constant being "v", is directly proportionate. With the same speed, the faster tempo term will be used for that composition, the pulse of which is more densely utilized. The listener will receive more musical information in one unit of time, and will perceive the tempo as the faster one.

, where "v" is the speed of pulsation sought for the basic time unit (i.e. the metronome marking); "α" is a sign of proportion; "t" is the indication of tempo (term); "q" is the indicator of the melodic content of the rhythmic units which allows one to attribute the given example to any of the groups in the table; and "n" reflects the quantity of other elements which cause additional influence on tempo (rhythmic scale, time signature, articulation, textural details, etc.). According to this formula, the higher the tempo term, and the less saturated the melody and texture, the faster the speed of performance and vice versa. The correlation between "t" and "qn," with the constant being "v", is directly proportionate. With the same speed, the faster tempo term will be used for that composition, the pulse of which is more densely utilized. The listener will receive more musical information in one unit of time, and will perceive the tempo as the faster one.

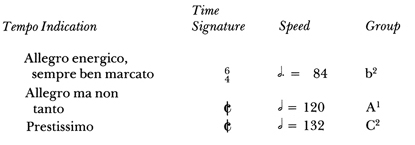

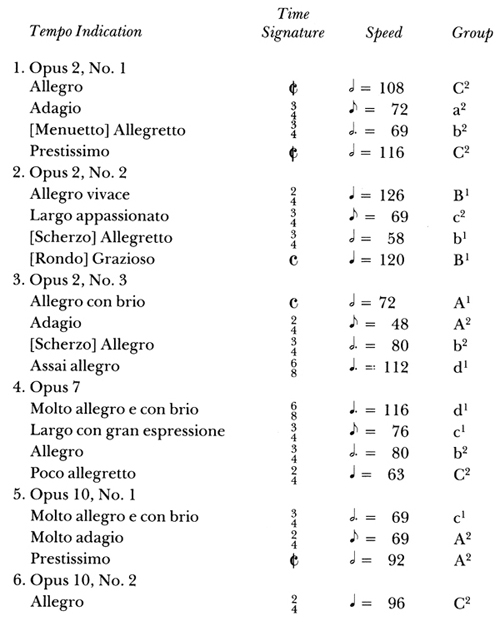

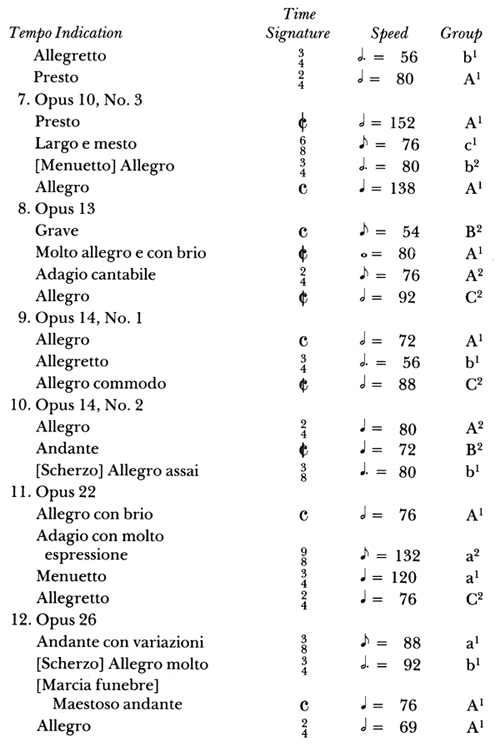

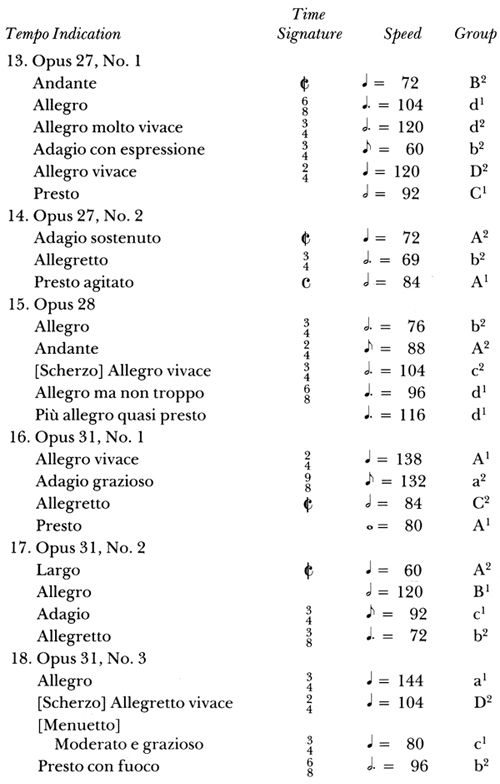

By using the described method, the author has established metronome markings for all piano sonatas and concertos of Beethoven. The results are shown in Table 3. This is derived from information contained in Table 2b.

In examining some examples, an explanation is required of those movements in which the rhythmic scale influences the speed. The most interesting examples are the slow movements of Sonatas Op. 2/3 and Op. 13. The metronome markings have been calculated by comparison with the slow movement of the Ninth Symphony.

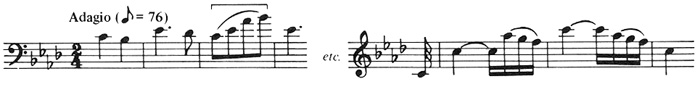

Example 10

a. Symphony No. 9, Opus 125, 3rd Movement, measures 3, 16.

b. Sonata Opus 13, 2nd Movement, measures 1, 17.

c. Sonata Opus 2, No. 3, 2nd Movement, measures 1, 11.

In relation to the ordinary rhythmic scale of the Pathètique Sonata, IX3 and 32 present augmented and diminished rhythmic scales, so that different rhythmic units appear in the same functions. Here a comparative analysis is needed, not only of the figuration, but also of the notes of greater value (in the examples, these are marked with brackets).

The method of metronome markings follows Beethoven's (see footnote 11). Accordingly, since the augmented rhythmic scale of the third movement of the Ninth Symphony results in  = 60, the corresponding figure for "adagio molto" in the ordinary scale would be

= 60, the corresponding figure for "adagio molto" in the ordinary scale would be  = 69 (skipping, by Beethoven's method, 63 and 66). Reserving the next figure (72) for "adagio sostenuto" (also suitable for the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata), we reach

= 69 (skipping, by Beethoven's method, 63 and 66). Reserving the next figure (72) for "adagio sostenuto" (also suitable for the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata), we reach  = 76 for the "adagio" of the Pathètique Sonata. Then, omitting the next two figures (80 and 84), we reach

= 76 for the "adagio" of the Pathètique Sonata. Then, omitting the next two figures (80 and 84), we reach  = 88 for the diminished rhythmic scale of example "c". Due to the deleted bar line (a binary measure of the "adagio" of Op. 2/3 is twice as long as one measure of the Pathètique), a sixteenth note comes to 92. Inasmuch as the time unit should be an eighth note, the result is

= 88 for the diminished rhythmic scale of example "c". Due to the deleted bar line (a binary measure of the "adagio" of Op. 2/3 is twice as long as one measure of the Pathètique), a sixteenth note comes to 92. Inasmuch as the time unit should be an eighth note, the result is  = 92:2 = 46. This process suggests that we should slightly increase the speed because we have made pulsation less frequent. So

= 92:2 = 46. This process suggests that we should slightly increase the speed because we have made pulsation less frequent. So  = 48 is the final result. Together with the slow movements of Sonatas Op. 101 and Op. 81a, this movement establishes a special new column of diminished rhythmic scale within group A2.

= 48 is the final result. Together with the slow movements of Sonatas Op. 101 and Op. 81a, this movement establishes a special new column of diminished rhythmic scale within group A2.

Slow movements having compound time signatures ( ,

,  , etc.) present an exceptional situation. Beethoven's metronome markings of 132 and 138 in the "adagios" of Quartet Op. 18/1 and Septet seem to be high, but they are for the eighth note. The melodic notes are of greater value and the movement is actually slow (

, etc.) present an exceptional situation. Beethoven's metronome markings of 132 and 138 in the "adagios" of Quartet Op. 18/1 and Septet seem to be high, but they are for the eighth note. The melodic notes are of greater value and the movement is actually slow ( = 44-46). The author followed these indications in calculating the metronome markings for the "adagios" of Op. 22 and Op. 31/1, which are also written in

= 44-46). The author followed these indications in calculating the metronome markings for the "adagios" of Op. 22 and Op. 31/1, which are also written in  and have similar rhythmic settings and textures.

and have similar rhythmic settings and textures.

The last three sonatas, Op. 109, 110, and 111, deserve separate examination. Beethoven's innovative endeavors in form clearly have had their effect on tempo. The problem is the integrity of the sonata form. A very important role is assigned to tempo. In these three sonatas there are obvious rhythmical equivalences which strengthen the sonata form, notwithstanding the multitude of diversified episodes, and the freedom of construction. This is especially obvious in Op. 111. In the first movement the transition from introduction to the main section is implemented by having the thirty-second notes of the "maestoso" equal in speed to the sixteenth notes of the "allegro con brio ed appasionato." Accordingly, the metronome marking of the "maestoso" should be half that of the "allegro con brio":  = 72—

= 72— = 144.13 Consequently, the tempo of the introduction exceeds the traditional one. We must consider, however, the arpeggio passages, the rests, and other rhythmic details which require certain deviations from strict tempo. In the "Arietta," the rhythmic equivalence of the theme and the succeeding variations is indicated by the phrase "l'istesso tempo," but the increase of the speed is accomplished by rhythmic subdivision. In the suggested metronome markings, it is considered possible to venture further along this line and have a rhythmic equivalence stated between both movements of the Sonata. The indication

= 144.13 Consequently, the tempo of the introduction exceeds the traditional one. We must consider, however, the arpeggio passages, the rests, and other rhythmic details which require certain deviations from strict tempo. In the "Arietta," the rhythmic equivalence of the theme and the succeeding variations is indicated by the phrase "l'istesso tempo," but the increase of the speed is accomplished by rhythmic subdivision. In the suggested metronome markings, it is considered possible to venture further along this line and have a rhythmic equivalence stated between both movements of the Sonata. The indication  = 48, means that

= 48, means that  = 144. Thus,

= 144. Thus,  =

=  of the "allegro con brio." The same principle is applied to the finale of Op. 110. The ratio of 1:2 is used here, with the result that the time unit of the "allegro ma non troppo" is twice as fast as that of the "adagio ma non troppo."

of the "allegro con brio." The same principle is applied to the finale of Op. 110. The ratio of 1:2 is used here, with the result that the time unit of the "allegro ma non troppo" is twice as fast as that of the "adagio ma non troppo."

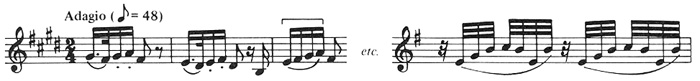

This problem is treated somewhat differently in the finale of Op. 109. In this variation cycle Beethoven changes the tempo indications many times, as if he were contemplating a ternary form. The theme, along with the first two variations, and the final variation ("andante"), form the frame of the central episode, where each variation has its own tempo indication. A rhythmic equivalence cements the form: a quarter note in the "allegro vivace" ( = 72,

= 72,  = 144) equals an eighth note of the next variation "poco meno andante" (

= 144) equals an eighth note of the next variation "poco meno andante" ( = 48,

= 48,  = 144). The half note of the "allegro ma non troppo" (

= 144). The half note of the "allegro ma non troppo" ( = 96 ) doubles the speed of the time unit of the preceding variation.

= 96 ) doubles the speed of the time unit of the preceding variation.

Incidentally, the episode "poco meno andante" in the finale of Op. 109 gives reason to discuss the problem of the "intermediate" tempos introduced by the words "poco più," "poco meno," etc. The analysis of Beethoven's metronome markings (see Tables 1 and 2) demonstrates that in all of these cases there is a transition to other groups on the same tempo level. For example, the "Menuetto" of the Fourth Symphony is marked "allegro vivace,"  = 100, and placed in group c2. For the "Trio," Beethoven indicates "poco meno allegro,"

= 100, and placed in group c2. For the "Trio," Beethoven indicates "poco meno allegro,"  = 88. The proper place for this episode is in a different category of "allegro vivace," in group b2. Naturally, the same method was applied in similar cases (see 154, 222, 231, 303, 313).

= 88. The proper place for this episode is in a different category of "allegro vivace," in group b2. Naturally, the same method was applied in similar cases (see 154, 222, 231, 303, 313).

This completes the short analysis of Beethoven's piano works. The general survey of Table 3 confirms the possibility of using the comparative method to obtain correct tempos. Nonetheless, the author considers it necessary to point out that this does not mean that the results of this analysis are obligatory; it is a suggestion supported by valid arguments. The important point is not so much in the result of any particular case, but the analytical method itself. Additionally, the limited scope of Table 2b should be noted. This Table serves the purpose of classification, but can be broadened in any direction because of the infinitely possible combination of various types of rhythmic setting, the nuances of tempo indication, and the different types of texture which influence speed. The Table, thus, indicates patterns and assists the understanding of general principles underlying the composer's use of tempo terminology.

The results of this analysis can be summarized in the following basic statements:

- By providing a composition with a tempo indication, the composer implies not a possible zone of tempo, but a quite definite speed of pulsation.

- If it is not indicated by a metronome marking, the task of the performer is to find the composer's intention. This can be accomplished by analyzing the melodic content of the figuration, and by examining the rhythmic and textural peculiarities of the work.

- Traditional tempo terminology constitutes a stepwise system: the faster tempo indication should correspond to the higher speed, and the slower to the lesser. This simple rule, however, can be traced without analysis and adjustments only if, in the compared works, the melodic structure of the same time units is similar, and other factors coincide.

- Metronome markings for the same tempo indication vary to the extent that the melodic structure is different, and that the note values used in the same melodic function are variously grouped (for example, by three or four). Hence, the multitude of different metronome markings obscure tempo terminology, and impede its comprehension.

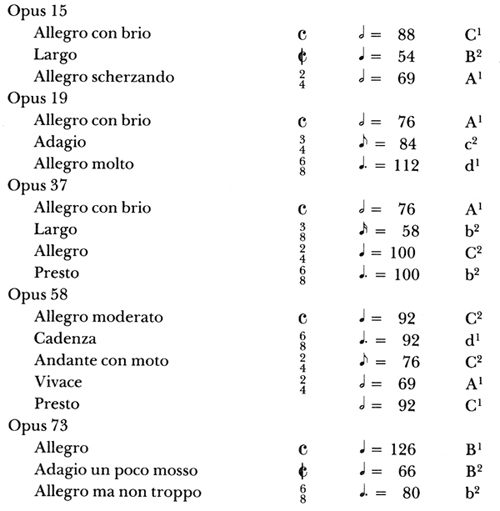

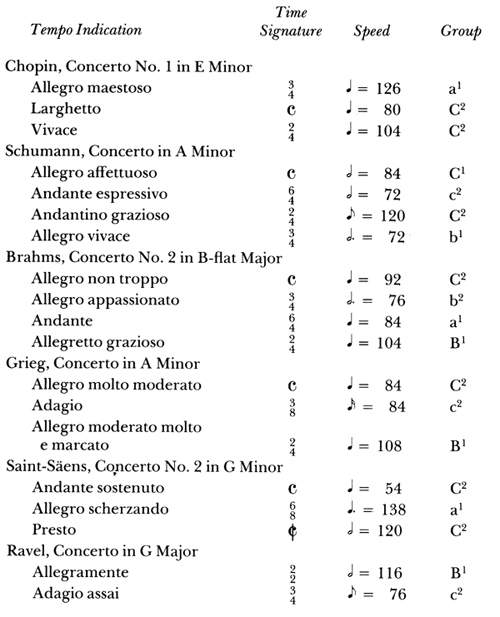

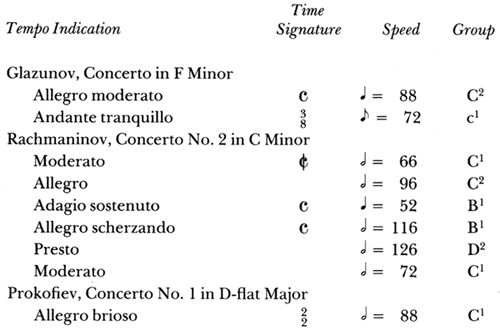

The conclusions on the nature of tempo terminology are based on an analysis of Beethoven's compositions. There arises the question: in what degree are these conclusions applicable to the works of other composers? Within the scope of this article it is only possible to suggest that the analytical method is comprehensive, and can be applied to music of other composers.14 Of course, the method can be applied to the predecessors and older contemporaries of Beethoven, who lived in the pre-metronome period, and to the early romantics. Their music stands the nearest to Beethoven's in style and the same principles of analysis can be applied. As for the romantics of the post-Beethoven epoch, and the composers of the first half of the twentieth century, almost all of these composers made use, to some extent, of traditional tempo indications and metronome markings. An analysis of their method of marking tempo could have helped to find an answer to the problem. Because of the immensity of the material, the analysis shall be limited to one important genre—the piano concerto. Depending on the way the composer's metronome markings for piano concertos correlate with the table of Beethoven's metronome markings, we can determine whether the deductions are applicable to music of other styles. Table 4 demonstrates that if a composer employs the traditional rhythmic settings, his music can be considered from the same viewpoint as Beethoven's music; consequently, this analytical method may be extended to tempo terminology in general.

The next important question to be discussed is related to the concept of the composer's tempo as the only possible one. This research shows that by the tempo indication and metronome marking, the composer attempts to fix his intention exactly. There arises the question of how objective this intention is. Can the composer's metronome marking be considered as a casual one, or even as the result of a mistake? In this case, the performer would have the right to supply his own corrections, which would "rectify" the composer's intentions.15 In other words, the question of whether the "correct tempo" is a hindrance to the freedom of the performer's individual creativity must still be answered. An attempt will be made to formulate a brief answer to this question, guided by the opinions of outstanding musicians.

"I expose my own feelings by means of tempo, phrasing and dynamic nuances of the music itself," said Sergei Rachmaninov in an interview, "and in the general outlook it gives the idea of my conception. But any prominent pianist can play my music in separate details, in nuances and shades quite differently from myself, and nevertheless, in the whole, the conception would not suffer because good taste and musical feeling of the genuine performer would prevent it."16 Apparently, the composer, during the creative process, expresses the main idea without considering nuances in detail. Therefore, in his work, he suggests not the interpretation itself, but rather its general plan. Wilhelm Furtwängler shares this dual concept of "intention and interpretation." Interpretation, in Furtwängler's words, "will naturally differ, in conformity with the conductor's individuality." He continues, however: ". . . actually for each work there is (despite the slight external deviations) only one conception, only one execution inherent in the music, peculiar to it, correct."17 Thus, according to the belief of both these great musicians, different interpretations appear within the scope of the same single conception. Ideally, these interpretations are congenial to the composer's intention.

"The diversity in the bounds of the similar is one of the mysteries of all arts," remarked Andrè Maurois. The genuine interpretation presents a synthesis of the composer's general idea and the performer's individual understanding. Without doubt, each of these aspects finds expression in the life of music time: the former in the steady beat of metrics (tempo), the latter in the living breath of rhythm. The tradition of reciprocity between rhythm and meter, the tension between them, goes to the very source of art in the performance of music. Monteverdi differentiated between "tempo della mano" (tempo of the hand) and "tempo dell'affetto dell'animo" (tempo of emotion). A significant deviation from balance inevitably brings the musician either to soulless scholasticism or to affectation. The correct tempo also keeps the performer from distorting the composer's intentions, because it springs from the very content and structure of a composition. "The unit of the note and tempo appear in my imagination at the same time as the interval itself," Stravinsky testifies.18 Therefore, it would be a delusion to consider the metronome markings and the tempo indications chosen by a composer to be arbitrary. Thus, one can speak about objectivity of tempo in the sense of its being independent not only of the performer, but, to a certain extent, of the composer himself. This feeling of almost fatal predestination in the creative process was characteristic of many great musicians, and was especially so of Beethoven. The great composer wrote on the score of his last Quartet: "Es muss sein!"

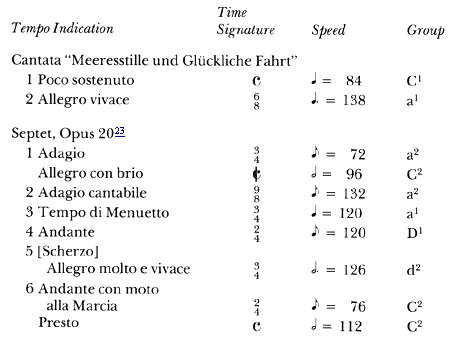

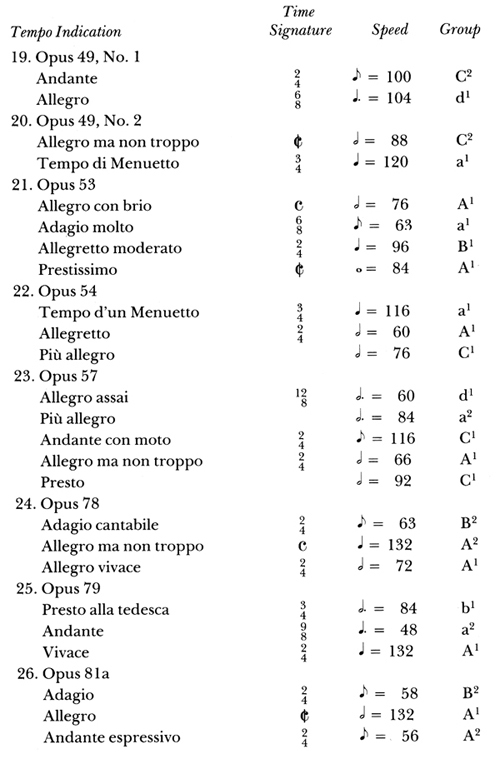

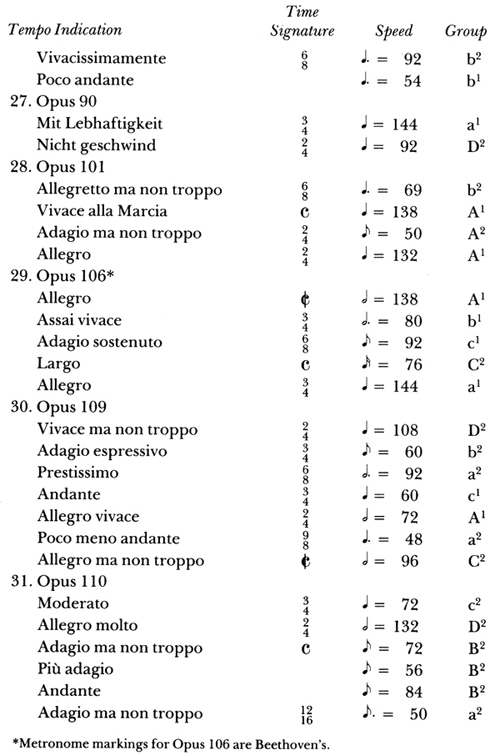

TABLE 1

Beethoven's Metronome Markings

SYMPHONIES I-IX19

TABLE 1 continued

SYMPHONIES I-IX

TABLE 1 continued

SYMPHONIES I-IX

TABLE 1 continued

SYMPHONIES I-IX

QUARTETS 1-1120

TABLE 1 continued

QUARTETS 1-11

TABLE 1 continued

QUARTETS 1-11

TABLE 1 continued

QUARTETS 1-11

OTHER COMPOSITIONS

TABLE 1 continued

OTHER COMPOSITIONS

TABLE 2a

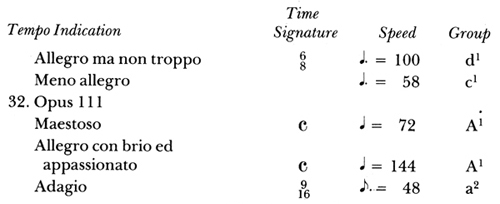

TABLE 3

Author's Metronome Markings for

Beethoven's Piano Sonatas and Concertos

SONATAS24

TABLE 3 continued

SONATAS

TABLE 3 continued

SONATAS

TABLE 3 continued

SONATAS

TABLE 3 continued

SONATAS

TABLE 3 continued

SONATAS

CONCERTOS25

TABLE 4

Composer's Own Metronome Markings

for Various Piano Concertos

TABLE 4 continued

1Some twentieth-century composers do indicate a zone, but usually even they restrict themselves to the nearest figures on the metronome scale.

2However, from this point of view the indication of tempo is not necessary for the music of the nineteenth century, either. It is quite clear that even without the markings "allegro," "presto" and "vivace," Chopin's Etudes Nos. 1, 4 and 5 from Opus 10 are fast pieces.

3The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 2nd edition, ed. Emily Anderson (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1966).

4Conversations with Igor Stravinsky, ed. Robert Craft (New York: Doubleday, 1959), pp. 135, 133.

5Hugo Riemann, Das Musikalische Lexikon (Berlin: Max Hellers Verlag, 1922), p. 1283.

6Czerny noted the following metronome markings: for Opus 10/2,  = 104, and for Opus 14/2,

= 104, and for Opus 14/2,  = 80.

= 80.

7Metronome markings are the author's.

8Space limitations for the Table compel the use of abbreviations: The numbers of symphonies will be indicated by a Roman numeral; the number of the movement by a raised Arabic numeral. For example, VII4 means: The Seventh Symphony, fourth movement. In the quartets, the "inversion" is used: 7IV reads as The Seventh Quartet, fourth movement. In the sonatas, both figures are in Arabic: 291 means the 29th Sonata, first movement. The above abbreviations are used further in the text of this article.

9This Table partly coincides with "Tabelle 1" contained in Hermann Beck, "Bemerkungen zu Beethoven's Tempi," Beethoven Jahrbuch II (1955-56), 39. One can also find it in William S. Newman, "Tempo in Beethoven's Instrumental Music," The Piano Quarterly 116 (Winter 1981-82), 26. The author's method of analysis and conclusions, however, differ entirely from Beck's.

10Metronome markings are the author's.

11Let us keep in mind two omitted numbers on the metronome scale (88 and 92). One can find the same differences in slow tempo as well. Compare three examples of "adagio ma non troppo"  = 60 (101),

= 60 (101),  = 69 (7IV),

= 69 (7IV),  = 80 (6II). This method will be applied later in this article.

= 80 (6II). This method will be applied later in this article.

12The puzzling sign

employed in Schubert's Impromptu Opus 90, No. 3, can be understood from this point of view. This double sign refers the performer from the speed of the augmented rhythmic scale directly to the speed of the diminished rhythmic scale, skipping the ordinary scale.

employed in Schubert's Impromptu Opus 90, No. 3, can be understood from this point of view. This double sign refers the performer from the speed of the augmented rhythmic scale directly to the speed of the diminished rhythmic scale, skipping the ordinary scale.

13This method is later applied by Chopin whose "doppio movimento" doubles the tempo.

14A possible exception might be the most modern compositions where the form of rhythmic setting itself has changed.

15We consider here only the composer's intentions and not the possibility of realizing them in practice. About these there can be some doubt (in particular, as to the extreme metronome markings for the fast movements of the "Hammerklavier" Sonata); however, one must not forget the advice of Beethoven expressed in the comment on the metronome marking of the song "North and South:" "100 accordingly to Maelzel; yet this can only apply to the first measures, since feeling also has its beat, which cannot be conveyed wholly by a number (that is, 100)." See: A.B. Marx, Anleitung zum Vortrag Beethovenscher Klavierwerke, 3rd Edition (Berlin: O. Janke, 1898), p. 69.

16The Musical Observer 20, no. 4 (April 1921), 11-12.

17Wilhelm Furtwängler, Gespräche über Musik (Zurich: Atlantis Verlag, 1948).

18Conversations with Igor Stravinsky, p. 20.

19Metronome markings for Symphonies Nos. I-VIII were published in the Leipzig Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, No. 51 (December 17, 1817). For the facsimile of the Ninth Symphony see: Peter Stadlen, "Beethoven and the Metronome," Music and Letters 48, No. 4 (1967), 330-349.

20Reprinted in Gustav Nottebohm, Zweite Beethoveniana (Leipzig, 1887), p. 519, with reference to the S.A. Steiner edition, Vienna.

21The metronome markings are stated in the letter from Beethoven to Ferdinand Ries of April 16, 1819. Beethoven's Letters (1790-1826), from the Collection of Ludwig Nohl, trans. Lady Wallace (New York: Leypoldt and Holt: 1867), II, 38 (No. 261).

22Authenticity of these metronome markings is doubtful.

23Published with the metronome markings for the quartets.

24One may compare the author's results with the table of metronome markings for Beethoven's sonatas given by Czerny, Moscheles, Bülow, and Schnabel, and reproduced in Kenneth Drake, The Sonatas of Beethoven as He Played and Taught Them (Cincinnati: Music Teachers National Association, 1972), pp. 36-41.

25One may compare the author's results with metronome markings given by Czerny and Kullak.