In 1933, the twentieth-century Russian composer Alexander Tcherepnin (1899-1977) arrived at a crucial time in his creative life: he was searching for a new direction or impetus for his composing. His own music had reached a kind of impasse where complexities (interpoint and nine-step scale)1 made composition a difficult task, and he wanted to find a simpler and more direct approach for expressing his art. Tcherepnin's biographer, Willi Reich, relates how "fate" gave the composer the answer to his problem:

It was primarily an external cause which led Tcherepnin to the Far East: the American manager A. Strock had scheduled him for spring and summer of 1934 for a concert tour around the world, which was to begin in April in China. The rest of the tour was to take place in Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, then go to Egypt and Palestine. For the next season he was scheduled again for Europe and America.

But everything happened differently: after the first concerts in Shanghai, Tcherepnin met his friend, the pianist Boris Zakharoff, who taught at the conservatory there. Among the students whom Zakharoff introduced to him was the highly-gifted young Chinese pianist Lee Hsien Ming, for whom Tcherepnin immediately felt a strong attraction.

After only their first meeting, he made the firm decision to marry Lee Hsien Ming. In order to be able to stay near her, Tcherepnin cancelled the rest of his tour responsibilities, and instead took on new concerts in China and Japan, an honorary professorship at the conservatory in Shanghai, and the post of an advisor for music education with the Chinese Education Ministry. All the greater was his disappointment when Miss Lee received a stipend for her excellent piano playing and, in the fall of 1934, went to Europe to continue her education. The two were not to see each other until three years later.2

And so a concert tour, and an affair of the heart quickly plunged Tcherepnin deeply into the cultures and native music of China, where he became something of a temporary resident from 1934 to 1935 and from 1936 to 1937.3

In his initial year in such large cities of China as Shanghai, Nanking, Tientsin and Peking, Tcherepnin was able to hear Chinese piano students and observe their particular problems. Because of the European training of many of the musical leaders in China (this was the era when study in Europe was the "accepted thing" for the serious classical musician), the newly-founded schools and conservatories of China were naturally fashioned after their European models. At first glance, this noble tradition of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms et al., would appear to be good and proper for Chinese music education, yet to Tcherepnin's thinking this was not true. The difficulty lay in the fact that the occidental and oriental cultures were slightly removed from one another, at least when the so-called universal language of music was considered. Tcherepnin noticed that the young Chinese piano students were having difficulty in adapting to a foreign instrument (the piano) and a foreign music (namely, European classical). He reasoned that the music education process could be more easily achieved if familiar music (specifically, Chinese folk music) could be adapted to the piano in a modern manner, thus eliminating one of the "unknowns" in the pupil's work. It is interesting that Tcherepnin thought that these exercises should be followed by compositions from more recent composers, "beginning with Debussy (especially congenial to the Chinese ear through the Javanese affinity in his art) and Stravinsky, and leading to the best works of the post-war musical literature."4

Thus the need for pedagogical music based upon native Chinese music, rather than European classical music, prompted Tcherepnin to explore Chinese folk music, and, at first, to compose pedagogical piano pieces based on these investigations. However, Tcherepnin became so enamored with the world of the pentatonic that he kept it among his musical vocabularies, even to the point of constructing a complete theoretical system based upon it.5

PIANO METHOD ON PENTATONIC SCALE

With his usual missionary zeal, Tcherepnin began the task of composing in the autumn of 1934 at Shanghai, continued at Myanoshita (Japan), and completed at Peking in early 1935, his Piano Method on Pentatonic Scale (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The cover and title page of Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale.

No copyright. Published 1935 by Commercial Press, Shanghai.

It was published in the first part of 1935 by the National Conservatory of Music at Shanghai through that city's Commercial Press, as a text for its students, and was later adopted by the Chinese government for use in all schools and universities in China in the 1930s.6 This method was published with a preface in Chinese by Dr. Hsiao Yui-Mei, then Director of the National Conservatory at Shanghai, who also provided the titles (in English and Chinese) and the minimal directions (only in English) as to fingerings and ways to practice, written throughout the text.7

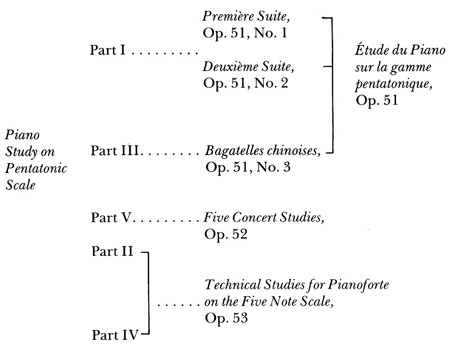

This one-volume, forty-three-page piano method (in five parts) is a kind of "Gradus ad Parnassum" progressing from the simplest pieces through the intermediate level and culminating in a concert piece.8 From this method, in order to obtain copyright, three later opus numbers were compiled in total or in part: (1) Étude du Piano sur la gamme pentatonique, Op. 51 (consisting of Première Suite, Op. 51, No. 1; Deuxième Suite, Op. 51, No. 2; and Bagatelles chinoises, Op. 51, No. 3); (2) Five Concert Studies, Op. 52; and (3) Technical Studies for Pianoforte on the Five Note Scale, Op. 53. Table 1 shows the relationship of the five parts of the Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale and the three "extracted" Opp. 51, 52 and 53. Tcherepnin agreed with me that these four works—Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale, and Opp. 51, 52 and 53—could be appropriately called a "Chinese Mikrokosmos."9

Table 1. The Organization of Tcherepnin's Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale.

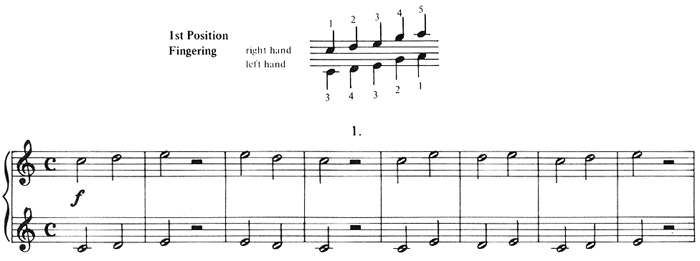

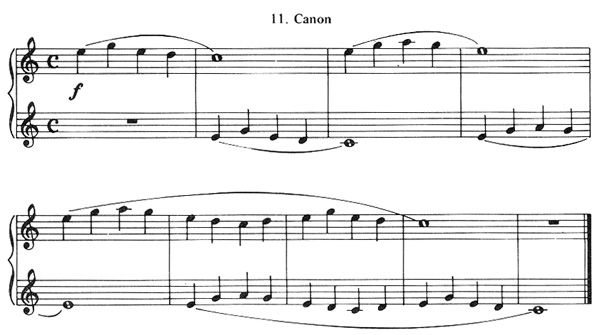

Considered as a form, the five parts of the Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale are arranged symmetrically like a rondo: Parts I, III and V contain pieces, while Parts II and IV consist entirely of technical exercises, scales and arpeggios. The thirty short pieces in Part I are all in C major pentatonic. The first twenty-three pieces are in one-hand position (both hands) in Mode I of the pentatonic (C, D, E, G, A). See Example 1 for the opening measures of the very first piece, and Example 2 for the entire eleventh piece.

Ex. 1

Ex. 2

While the first fifteen pieces do not have any tempo indications, the remainder do. No. 24 is in Mode V (A, C, D, E, G); No. 25 in Mode IV (G, A, C, D, E); Nos. 26 and 27 in Mode III (E, G, A, C, D); No. 28 in Mode II (D, E, G, A, C); and Nos. 29 and 30 in a mixture of modes. Première Suite, Op. 51, No. 1, and Deuxième Suite, Op. 51, No. 2, were extracted from these thirty pieces: the former amounted to Nos. 16-22 (slightly reordered) and the latter, Nos. 23-28 and 30 (more radically reordered).10 The level of difficulty is very easy to easy.

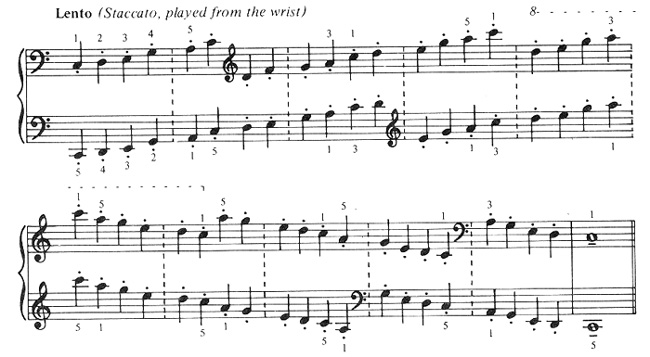

Part II of the Piano Study consists only of major pentatonic scales (with their fingerings) in all keys. When played with hands together at the octave, the scales are to be played over a five-octave range in staccato (lento quarter notes, as in Example 3) and legato (lento duple eighth notes, moderato triplet eighths and allegro quadruple sixteenths).

Ex. 3

When played with alternating hands (groups of five notes each), the range is four octaves, staccato (lento duple eighth notes, as in Example 4) and legato (allegro quadruple sixteenths).

Ex. 4

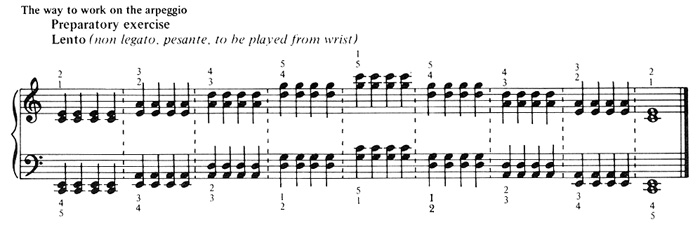

Because of the special problems of crossing the thumb under the fifth finger and reaching the fifth finger over the thumb in playing these scales, there are "preparatory exercises" which focus on this special technique by repetitive patterns in quarter notes, duple eighth notes, triplet eighths and quadruple sixteenths (Example 5).

Ex. 5

These exercises bring to mind similar exercises of various pedagogues, e.g., Cortot, Philipp, et al. This Part II was later incorporated into Technical Studies for Pianoforte on the Five Note Scale, Op. 53. The level of difficulty is easy to moderately difficult.

The "12 Short Pieces" of the middle part (Part III) of the Piano Study are a bit larger than those of Part I. The dozen pieces are arranged in a circle of fifths of major pentatonic scales, the first on C and the last on F. This part was later republished in total (with individual titles translated from English into French) as Bagatelles chinoises, Op. 51, No. 3. The level of difficulty is moderately difficult.

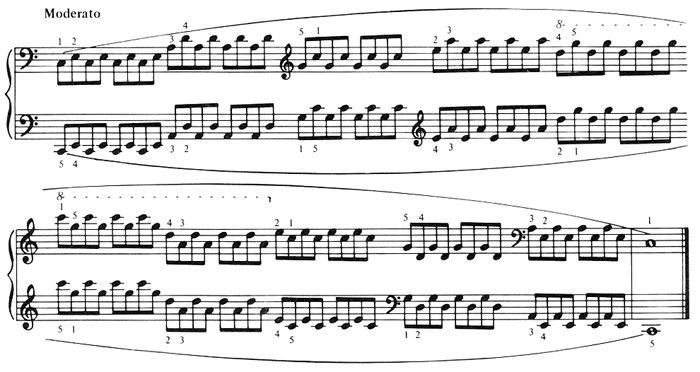

The second to last section, Part IV, is devoted exclusively to major pentatonic arpeggios (with their fingerings) in all keys. Played only with hands together at the octave, the arpeggios are to be played first as two-note chords in lento quarter notes over a two-octave range in "preparatory exercises" (Example 6),

Ex. 6

then in two-note trill-like figures in moderato duple eighth notes (Example 7), moderato triplet eighths and moderato quadruple sixteenths, all over a four-octave range.

Ex. 7

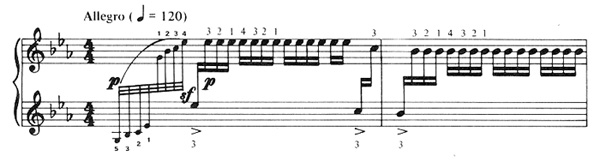

Finally, they are to be played in arpeggio form, also over a four-octave range, in staccato lento eighth notes (Example 8), legato moderato triplet eighths, and (allegro?) quadruple sixteenths.

Ex. 8

Again, like Part II of this method, this part recalls similar material by famous pedagogues; this part was also later incorporated in Technical Studies for Pianoforte on the Five Note Scale, Op. 53. The level of difficulty is difficult.

The final part, Part V, of the Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale consists of only one composition, a concert piece titled, "Hommage à la Chine." This difficult concert etude demonstrates the use of the pentatonic scale in a serious virtuosic work which exploits repeated notes (Example 9). This piece was later used as the third etude in Five Concert Studies, Op. 52.

Ex. 9

Our discussion to this point has viewed the "mother" opus, Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale, in the prime position it demands. But now, it is essential that we also examine the "children" opus numbers, Opp. 51, 52 and 53, in more detail and in their own right.

ÉTUDE DU PIANO SUR LA GAMME PENTATONIQUE, OP. 5111

The three parts of this opus—Première Suite, Deuxième Suite, and Bagatelles chinoises—were all published in the latter part of 1935 in Paris by Heugel (edited and fingered by Isidore Philipp). There are a total of twenty-six pieces: seven pieces in each of the two suites, and twelve bagatelles. In level of difficulty, the first suite is easy, the second suite slightly more demanding, and the bagatelles moderately difficult.

Première Suite, Op. 51, No. 1

These slight pieces all have a five-finger range and a single hand position throughout (on C, D, E, G, A—C major pentatonic, Mode I) for both hands. One-part form in Nos. 1 and 3; three-part form in Nos. 2 and 4-7. The small phrases should be easily comprehended by the beginning piano student. These French-titled miniatures have a varied, though limited, range of expression and touch. No. 1 (Mélodie) is a legato study for both hands, similar to Robert Schumann's little pieces from Album for the Young, Op. 68 (Example 10), while No. 4 (Fox-Trot) is a humorous march-like parody with accents on the last beats of the measures.

Ex. 10

Deuxième Suite, Op. 51, No. 2

C major pentatonic is used again throughout, but here, unlike the Première Suite, all five modes are introduced—thus the student experiences new hand positions. There are three types of forms: one-part form in Nos. 2 and 4; three-part form in Nos. 1, 3, 5 and 6; evolving form in No. 7 (generally, the forms are larger than those found in the Première Suite). No. 4, Andantino (in Mode III: E, G, A, C, D), is a tiny eight-measure march with two repeated-note fanfares in soft chordal texture followed by surprise phrase endings in loud dynamics (see Example 11 for the second phrase).

Ex. 11

For an interesting study of clanging tone-clusters built on every possible chord of the C major pentatonic scale, the reader might investigate No. 7, Maestoso (in all five modes).

Bagatelles chinoises, Op. 53, No. 3: 12 Pieces courtes

These twelve short pieces were dedicated to ten young Chinese pianists (Nos. 1 and 3-11), who took part in a concert of the Bagatelles, Op. 5 (of Alexander Tcherepnin), in Peking, and their teacher, Mr. C.T. Yan (No. 12); the one left (No. 2) is dedicated to the Pi-Bah virtuoso, Miss Tsao An Ho, who taught Tcherepnin to play that guitar-like instrument.

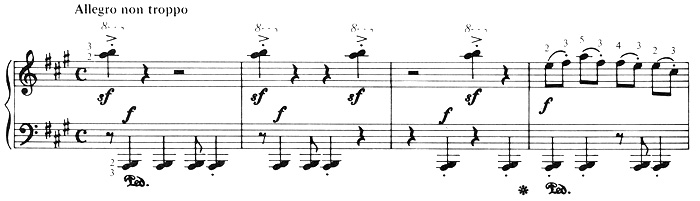

The dozen keys (C, G, D, A, E, B, F-sharp, D-flat, A-flat, E-flat, B-flat, and F), arranged in a circle of fifths, and all based on the major pentatonic scale (Mode I), give the student multiple key experience. Demands upon the performer reach moderately difficult levels in different forms and textures: No. 1, Allegro (C major), serving as a prelude to the whole set, simply repeats two eight-measure phrases with altered accompaniments and increased dynamics; a striking effect of drum and fife is achieved in No. 4, Allegro non troppo (A major), by the use of extreme outer ranges of the keyboard (Example 12);

Ex. 12

and a three-part form with extreme contrast between parts (middle section staccato and primarily rhythmic, while the outer sections are legato and lyric) is exhibited in No. 6, Lento (B major). In addition to his own invented melodies, Tcherepnin also uses popular authentic Chinese tunes in Nos. 9 and 10.

FIVE CONCERT STUDIES, OP. 52

When we examine the etudes of Op. 52, we are viewing the crown, so to speak, of the "Chinese Mikrokosmos." It would seem inevitable to compare them with the Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm in Volume 6 of Béla Bartók's Mikrokosmos. The location in the overall plan of these works, however, is really the only thing which these two sets of pieces have in common: the Tcherepnin etudes are more greatly varied than the more unified Bartók dances, and explore more technical (pianistic) problems and contain more varied textures and sonorities. These are difficult and effective concert numbers, each having an individual form suitable to its own material and evolved from it. All were published in 1936 by B. Schotts Söhne, Mainz; their first performance was the same year in Tokyo by the composer.

1. Shadow Play: Animato (D major pentatonic). Composed in 1935 in Paris, this first etude is rich in contrasts with modulations within the pentatonic system.

2. The Lute: Moderato (C major pentatonic, Mode V). Inspired by the Chinese instrument "Kou Chin" and the traditional piece which Chinese musicians played upon it, this four-minute piece is played on one damper pedal. Dotted barlines and extremely soft dynamics (only ppp and pppp) emphasize the gentility of attack and accents. Heavy with Oriental charm, and showing a kinship with Alan Hovhaness's exotic sounds, this intriguing piece was written in Paris in 1935.

3. Homage to China: Allegro (E-flat major pentatonic). This middle etude was not only the first one of the group to be set to paper (1934 in Shanghai and Myanoshita), but was the first piece composed under the new Chinese influence: it was the composer's first "love offering" to his wife-to-be, Lee Hsien Ming. The repeated-note figurations were inspired by the Chinese Pi-Bah, which is played by silver "nails" (attached to the finger tips) in a pizzicato manner.

4. Punch and Judy: Allegretto (E major pentatonic). The tune used in this study was an actual popular melody that was used to accompany performers in marionette theaters in China. As might be expected, there are sudden dynamic and tonal shifts to portray the fun and violence (strange bedfellows, but typical) of these timeless children's puppet shows. This fourth etude was finished in 1936 in Paris.

5. Cantique: Lento (A major pentatonic, Mode V). Revealing yet again Tcherepnin's ability to complete his tasks in "transit," this last etude was completed in New York in 1936. Chinese folk music is also revealed here, for the theme is based upon an ancient Buddhist monk chant. With huge sonorities in a slow tempo, the final study rises to a climactic close with full chords and octaves like the ending of a regal procession.

TECHNICAL STUDIES FOR PIANOFORTE ON THE FIVE NOTE SCALE, OP. 53

When we turn to the final segment of the "Chinese Mikrokosmos," we encounter a book of exercises not unlike other pedagogical works devoted to technical exercises (e.g., Hummel, Hanon, Brahms, etc.). Here is a volume of exercises, written in C major pentatonic, which surveys a wide range of technical problems possible when using the pentatonic scale. Amplifying ideas originally published in the Piano Study of Shanghai, which only concerned itself with scales and arpeggios, this opus also includes exercises for double notes, octaves and chords, thus making it a valuable thesaurus of technique often needed for modern music which uses the pentatonic.12 There are two large parts, identically organized into the following subdivisions: scales, arpeggios, double notes, and chords—all of which have preparatory exercises to condition the mind and the fingers, and progress from slower to faster notes. All of the exercises naturally have to be transposed to all keys, and practiced in all touches, dynamic levels and gradations. The first part is based only on Mode I of the pentatonic; part two uses all five modes. An Appendix appears at the end of each of the two large parts: Appendix I contains fingerings for all pentatonic keys for five-note scales, arpeggios and double notes; Appendix II contains C fingerings for a synthetic scale (C, D, E-flat, E, F, G, A-flat, A and B-flat) for scales, arpeggios and double notes. This opus was realized over a period of years (1934-36) in the Orient, and was published by Peters (1936), Leipzig, in an edition prefaced, edited and fingered by Isidore Philipp.

CONCLUSION

Elsewhere I have labeled the fifteen-year time span from 1934 (the year of Tcherepnin's first China/Japan concert tour) to 1949 as the "Folk Cure" period in Tcherepnin's life.13 Yet it should be pointed out that these dates do not precisely mark the limits of folk-music influence upon Tcherepnin's compositions. Even in his youth in Russia (1899-1918) and in Georgia (1918-21), he had the opportunity to hear a great deal of native music, both in the churches and in secular concerts. Quite naturally, his own creative efforts often revealed his exposure to these various musics, either by direct quote or imitation. The discovery of Chinese folk music in the 1930s, plus a revival of his previous interests in Russian and Georgian music, was opportune for in the late 1920s, Tcherepnin had "embraced the so-called 'Eurasian' ideology."14

Tcherepnin was not alone in his folklore interests; the study of folk music was an interest shared by many early twentieth-century composers.15 Of these, certainly one of the most important was Béla Bartók, whose observations on the role and method of folk-music research seem particularly relevant to Tcherepnin's own activities in this field. In an essay in 1920, Bartók wrote:

In my opinion, the effects of peasant music cannot be deep and permanent unless this music is studied in the country as part of a life shared with the peasants. It is not enough to study it as it is stored in museums. It is the character of peasant music, indescribable in words, that must find its way into our music. It must be pervaded by the very atmosphere of peasant culture. Peasant motifs (or imitations of such motifs) will only lend our music some new ornaments: nothing more.16

Such a close relationship between composer and culture as Bartók advocated was achieved by Alexander Tcherepnin in the years 1934-35 and 1936-37 when he lived among the people of the Orient, the people who influenced him to create the "Chinese Mikrokosmos."

1Interpoint is a type of contrapuntal technique which stresses each voice's independence in the texture, rather than their mutual dependence. For more details, see Guy Wuellner, "The Theory of Interpoint," The American Music Teacher (January 1978), 24-28. For complete information about the nine-step scale (e.g., C, D-flat, E-flat, E, F, G, A-flat; A, B and C), see Guy Wuellner, "The Complete Piano Music of Alexander Tcherepnin: An Essay Together with a Comprehensive Project in Piano Performance" (unpublished DMA dissertation, The University of Iowa, July 1974), pp. 43-65.

2Willi Reich, Alexander Tcherepnin, 2nd revised ed. (Bonn: M.P. Belaieff, 1970), pp. 38-39. Trans. from the German by Guy Wuellner.

3In 1935-36, Tcherepnin returned to the United States and Europe for concerts. See Wuellner, "The Complete Piano Music," pp. 87-88, and footnote 73 at the bottom of p. 89.

4Alexander Tcherepnin, "Music in Modern China," The Musical Quarterly 21, No. 4 (October 1935), 398; and Alexander Tcherepnin, "Catalogue complet des oeuvres" (photostat of unpublished autograph manuscript, Paris, June, 1962), p. 42.

5Wuellner, "Piano Music," p. 90. Other later works of Tcherepnin which especially reveal the continuing influence of the Far East are: the ballet Trepak, Op. 55; Sept Etudes for piano, Op. 56; Seven Songs on Chinese Poems for voice and piano, Op. 71; the opera The Farmer and the Nymph, Op. 72; Fantaisie for piano and orchestra; the ballet Die Frau und ihr Schatten, Op. 79; Japanese Suite for orchestra; The Lost Flute for narrator and orchestra, Op. 89; and Seven Chinese Folk Songs for voice and piano, Op. 95.

6Apparently this method is still available and in use in the Orient, for a colleague of mine, Maurice Hinson, obtained a new copy of it there during a Far East tour in January of 1978.

7This and the bulk of the remaining information in this article is derived from my thesis, "Piano Music," pp. 222-252.

8The one-volume Piano Study on Pentatonic Scale naturally invites comparison with Béla Bartók's six-volume Mikrokosmos. In addition to its obvious smaller size, the Piano Study is intentionally limited to one sound system—the pentatonic scale, whereas the Mikrokosmos utilizes many different scales (major, minor, chromatic, whole-tone, etc.) and modes (phyrigian, mixolydian, etc.). It is interesting to note that they were composed at about the same time: Piano Study in 1934-35, and the Mikrokosmos from 1926 to 1939.

9Letter from Alexander Tcherepnin to Guy Wuellner, Bäch, Switzerland, September 1, 1971.

10Obviously, sixteen pieces from the Piano Study (Nos. 1-15 and 29), were not utilized in later publications, and are not copyrighted.

11For a collation of the various pieces of the Piano Study and the Étude du Piano, Op. 51, see Wuellner, "Piano Music," Table 5, pp. 233-234.

12For a collation of the various sections of the Piano Study and the Technical Studies, Op. 53, see Wuellner, "Piano Music," Table 6, p. 246.

13For a complete discussion of the five periods of Tcherepnin's life, see Wuellner, "Piano Music," pp. 39-124.

14Alexander Tcherepnin, "Basic Elements of My Musical Language" (photostat of unpublished autograph manuscript, New York, January 1962), p. 18; and Tcherepnin, "Catalogue," pp. 31 and 38; and Reich, Tcherepnin, p. 16.

15See Donald Grout, A History of Western Music, rev. ed. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1973), pp. 664-679, where many of these composers are mentioned in this discussion of the role of folk music in shaping twentieth-century music.

16Béla Bartók, "The Influence of Peasant Music on Modern Music," Melos (1920), as quoted by Sam Morgenstern, ed., Composers on Music (New York: Pantheon, 1956), pp. 424-425.