Should the study of popular music be considered a part, perhaps even an integral part, of the public school music curriculum? In 1967, music educators, philosophers, industrialists, scientists, theologians, governmental representatives, and others meeting in Tanglewood, Massachusetts answered that question:

Music of all periods, styles, forms, and cultures belongs in the curriculum. The musical repertory should be expanded to involve music of our time in its rich variety, including currently popular teen-age music and avant-garde music, American folk music, and the music of other cultures.1

Reasons given by those at Tanglewood for the inclusion of popular music included relevance (music outside the schools is the only "real" music for most of America's children) and proper balance (traditional music literature dominates and overbalances the present music education repertory).2 The relevance of popular music to today's music classroom is further underscored by more recent studies which indicate it to be the preferred choice of primary school students and teenagers.3

In 1965 those involved with the Manhattanville Music Curriculum Program, after observing innovative programs, noted the importance of considering "the students' frame of reference" when planning instruction.4 It certainly would seem more logical to begin with the "real music" of the students and to transfer concepts regarding harmony, rhythm, form, and so forth to less familiar music rather than to concentrate on analysis of less familiar classical works first and then transfer concepts to other forms and styles. If the approach that begins with the music of the students is to be implemented, it certainly is relevant to study the structure of that music in some detail.

Since the Tanglewood Symposium, many have acknowledged the merits of popular music study. In the preface to the series of textbooks entitled Popular Music, Vulliamy and Lee stated that the study of popular music helps students develop musicality, technical skill, and standards of excellence. Kern and Evans have suggested that the less formal organizational nature of popular music facilitates an "experimental" approach to the music that in turn helps develop improvisational skills. The study and performance of popular music, with its emphasis on amplified, non-acoustic sounds, has also been associated with a better understanding of sound synthesis.5

In the late 1960s, the Music Educators National Conference (MENC) addressed the issue of youth (rock) music and attempted to facilitate its inclusion into the classroom by devoting a large portion of the November 1969 issue of the Music Educators Journal to articles that made pedagogical observations and suggestions for the use of youth music. That same year MENC also initiated the Youth Music Institute.

One study in that issue listed general stylistic, melodic, and harmonic qualities of the rock music of the era. While some of these observations seem overly generalized, particularly considering the disparity between the various styles of rock, they are still worth considering as they present a general overview of the rock music of the late 1960s. Author Thomas MacCluskey stated that rock differs from other types of music in the following ways:

- Youth music differs from other forms of popular music in the consistent use of even eighth-note subdivisions rather than the long-short subdivision typical of swing and jazz.

- Rock melodies very often feature the lowered third and almost always the lowered seventh.

- Harmonically, rock is distinguished by the employment of

-I progressions as well as progressions in which the roots are separated by a third (e.g., I-iii and ii-IV).

- Structural sevenths, ninths, and thirteenths are avoided in rock harmonies.

- Rock employs non-symmetrical phrase structure when compared to jazz and in particular blues.6

Regarding points 2 and 3, MacCluskey is quick to point out that these diatonic alterations are a result of the use of modes other than major and minor as a basis for both melody and harmony. Specifically, the melodic flatted seventh and a major chord built on the flatted seventh scale degree are characteristic of the mixolydian mode.

Since the late 1960s, few scholarly works discussing the nature of popular music have appeared. However, the publication of the popular music texts by Vulliamy and Lee and Middleton and Horn, articles such as those by Pembrook and Russell, the conferences conducted by the International Association for the Study of Popular Music in 1981 and 1984, and the emergence of journals such as Popular Music and Society indicate a renewal of interest in popular music among researchers.7

This interest in popular music, however, must stimulate the following activity in order to affect a change in the field of music education. First, popular music must be bestowed an air of legitimacy through careful definition and categorization. As Hamm stated at the First International Conference on Popular Music, "There is no general agreement on just what is encompassed by the term 'popular music'."8 This can be further substantiated by the varieties of music discussed in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians under the heading "popular music." The sub-sets of blues, country, gospel, jazz, pop, rock, and soul must be analyzed to determine the compositional and performance practices associated with each. Boyle, Hosterman, and Ramsey9 have suggested that familiarity with these structural variables will enable teachers to present materials in listening situations in such a way as to maximize positive responses among the listeners. Meticulous analysis also would provide a basis for the next step—comparison among the categories and also to other types of music. Second, popular music researchers must continue to analyze the most current popular music so as to note changes in the field and also to provide instructors with up-to-date information on the pieces which are of interest to their students.

This study was undertaken with two purposes in mind. First, an attempt was made to identify the structure and elements of pop music through a stylistic analysis of several pop pieces from 1965 through 1984. Once a carefully researched body of information regarding popular music is in existence, teachers and those involved in teacher training at the university level should feel more comfortable in addressing that subject. Second, this study attempted to determine if MacCluskey's observations from 1969 are applicable to popular tunes of a twenty-year span.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

The first problem encountered in this study dealt with the selection of popular pieces to be analyzed. Hamm, in discussing the preeminence of Billboard's "Hot 100" rankings, reported that

generally, both the music industry and most people who write about popular music (journalists, critics, historians) give complete credence to these charts . . . and many writers on popular music base their arguments and conclusions on Billboard rankings.10

Therefore, Billboard's rankings were used in the selection of popular pieces. The top pop song from each of the years 1965-1984 was determined by using Billboard's annual Top 100 Pop Singles chart. The time span of twenty years was selected for three reasons. First, the researcher believed that this span represented a broad enough period to dilute or negate skewed data caused by fads such as disco and punk. Second, with the emergence of the Beatles, the mid-1960s was thought to represent a logical starting point. Finally, preliminary research had indicated that the acquisition of sheet music, sound recordings, and documentation for the popularity of certain pre-1964 tunes would be impossible.

After the selection decision was made, records (45-rpm recordings) and sheet music for each selection were obtained. Because sheet music is often inaccurate, each copy of notated music was checked against the sound recordings for mistakes, deletions, additions, and alterations. Two pieces of sheet music were out of print, so these two songs (Bette Davis Eyes and Shadow Dancing) were transcribed from recordings.

After the music had been selected, the next step focused on determining the extent and type of analysis to be used. If overly detailed analysis is undertaken, the reader can be inundated with seemingly meaningless data. If the analysis is too superficial, it may appear to have little relevance. As LaRue suggested, the music analyst must be careful to "keep a balance between what can be deduced only after hours of study and what can be readily noticed by a careful listener after several hearings."11 The researcher attempted to keep this in mind during the analyses of the pieces used in this study.

In attempting a stylistic analysis, the author decided to rely on suggestions from LaRue's Guidelines for Style Analysis. The pieces of music selected in this study were analyzed using LaRue's categories of sound, harmony, melody, rhythm, and growth. These categories include the following:

Sound —Length of piece, instrumentation/timbre, background vocals, dynamic contrast Harmony —Key or mode, modulations, harmonic vocabulary, unusual chords, cadence types, chord rhythm Melody —Range, degree of conjunct motion, ascending versus descending motion, direction changes, chromaticism, text setting, interval usage Rhythm —Meter, meter change, tempo, rhythmic patterns Growth —Form, phrase symmetry, ending (real or fade out)

In addition a miscellaneous category analyzed the following:

Misc. —Recording artists' popularity and text subject material.

While some of these categories are clear cut (e.g., length of piece), others require explanation. The dynamic contrast volume check was accomplished by using a VU meter adjusted so that the loudest place in each piece elicited a 0 reading. Voltage readings were recorded every five seconds throughout each piece and averaged. Since silence produced a reading of -20 in this setting, the dynamic range was -20 to 0.

The harmonic vocabulary was analyzed by tabulating the harmony during each beat of each piece. Chords were then grouped according to categories implying their function. Categories included tonic (I or i), subdominant (IV, iv, or ii), dominant (V or vii°), and secondary dominant. Other chords such as iii and vi and unusual ones such as  7 and

7 and  were subsumed under a category entitled "other." Because major chords built on lowered-seventh scale degrees may indicate the use of modes (specifically mixolydian, according to MacCluskey) other than the traditional major and minor, modal influences were also considered.

were subsumed under a category entitled "other." Because major chords built on lowered-seventh scale degrees may indicate the use of modes (specifically mixolydian, according to MacCluskey) other than the traditional major and minor, modal influences were also considered.

Melodic motion in each piece of music was analyzed by classifying each interval of the melody. Degree of conjunct motion was then assessed by determining what percentage of the total consisted of unisons and descending and ascending minor and major seconds. Direction change figures for each song were divided by tabulating the total number of melodic tones (minus repeated tones) and dividing by the number of times a melody changed direction.

The recording artists' overall five-year popularity was determined by using Billboard's Top 100 artists listings, both album and singles, for a given period. Artists' positions for the year of the number one hit, the two years preceding, and the two years following it were averaged to achieve an indicative popularity rating. If a group did not appear on the charts for a given year a value of 101 was assigned. Thus the possible range was limited to 0 through 101.

RESULTS

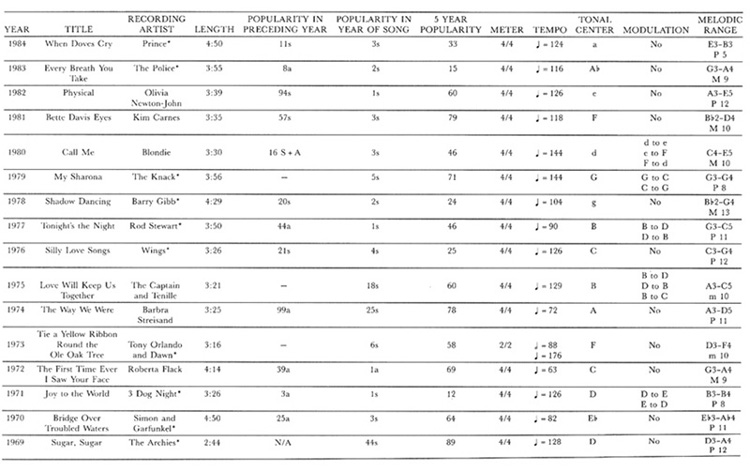

The selected tunes and recording artists from 1965 to 1984 are shown in Table 1. Qualities pertaining to sound, harmony, melody, and rhythm are also included. After the year and title, the next column lists recording artists. Approximately half of the number one tunes were written by the performing artists. There were no groups that had more than one number one song over the twenty-year span (although it should be noted that Paul McCartney was a member of both The Beatles in 1968 and Wings in 1976). Thirteen of the tunes featured a male vocal lead. These groups are indicated with an asterisk. Seven pieces were credited on the record label to a single artist and of these seven, five were by women.

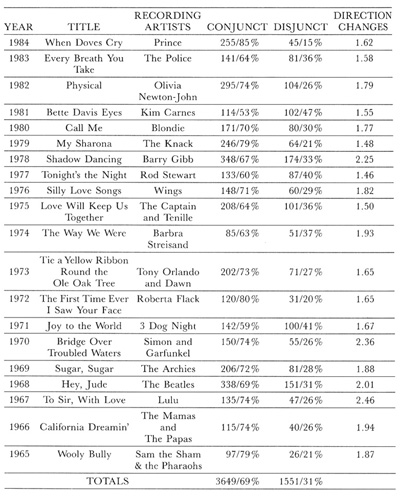

Table 1. General Characteristics of the 20 Pieces

Whether the piece featured one artist or a group of artists, the recording almost always exhibited the same instrumentation—keyboard, electric guitar, bass guitar, and drums. While some chose to augment this ensemble with brass (1982), woodwinds (1977), harmonica (1973), and strings (1970), very few used a thinner texture than the basic keyboard-guitars-drums combo. Only one song (1972) failed to include some sort of percussion.

The next column represents the length of each piece. Pieces ranged from 2:16—i.e., 2 minutes 16 seconds—(1965) to 7:04 (1968) with thirteen of the twenty pieces falling between 3:00 and 4:30. All of the pieces shorter than three minutes in length were recorded before 1970.

The popularity of the performing artists in the year preceding the release of each number one tune is listed in column five. In five of the eighteen years when data were available, the recording group was not on the Billboard's Top 100 singles or album chart for the year immediately preceding the year of their number one hit. Groups such as The Knack (1979), The Captain and Tenille (1975), and The Mamas and The Papas (1966) literally came out of nowhere to achieve instant fame. Of course, other groups—Prince (1984), The Police (1983), Three Dog Night (1971), and The Beatles (1968)—were already popular before attaining a number one hit.

Almost all artists achieved a very high ranking in either the single (indicated with an s in the figure) or album chart (indicated with an a) in the year their recording became popular. Those who did not, such as Barbra Streisand (1974), The Archies (1969), Lulu (1967), and Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs (1965), did not take advantage of their momentary success by producing other hit singles or albums. The five-year popularity rating indicates that many groups such as The Police, Prince, Wings, Three Dog Night, The Beatles, and others were already well established and/or remained very popular in the years after the appearance of their number one song. Scores over 50 in this column indicate a "flash in the pan" situation. (Possible exceptions include Barbra Streisand and Olivia Newton-John, who have had hits in years not examined in this study.)

An investigation of meter reflected one extremely consistent characteristic of popular music. All twenty tunes are in duple meter. Only one tune—Call Me (1980) changes meter. (It switches from 4/4 to 2/4 for one measure, then back again.) In almost all the recordings, once a tempo was established it was seldom interrupted or altered. Songs from 1967, 1973, and 1974 are exceptions to this rule, but the momentary ritards are of a very brief nature. Tempos ranged from  = 63 (1972) to

= 63 (1972) to  = 144 (1979 and 1980). Two songs (1965 and 1966) seemed to be interpretable as either 2/2 or 4/4 meter. While the tempos of the twenty tunes were divergent, eight of the twenty fell between

= 144 (1979 and 1980). Two songs (1965 and 1966) seemed to be interpretable as either 2/2 or 4/4 meter. While the tempos of the twenty tunes were divergent, eight of the twenty fell between  = 110 and 130. Subdivisions of the beat were simple (duple) in eighteen of the twenty cases, compound (triple) in the other two (1977 and 1980).

= 110 and 130. Subdivisions of the beat were simple (duple) in eighteen of the twenty cases, compound (triple) in the other two (1977 and 1980).

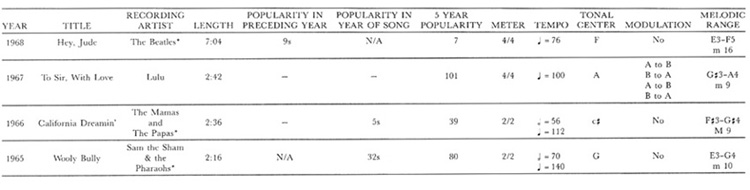

Melodic range varied from a perfect fifth (1984) to two octaves and a minor second (1968). Ranges are indicated using number 4 for the octave with middle c on the bottom, number three for the octave below middle c, number 2 for the octave below that and so forth. The average range was 15.85 half steps, approximately a major tenth. Referring to Garretson's voice classification table (see Figure 1)12 an interesting difference between the male and female vocal ranges can be noted. Twelve of the thirteen pieces by male singers do not exceed the lower limit of Garretson's suggested vocal range for the first tenor. Only the 1978 song goes below C 3. Eleven of the thirteen songs either exceed the upper limit of the first tenor or come within a major second of it. In short, the male vocal lines of the songs in this study were all fairly high. The female ranges, on the other hand, are lower, with the first or second alto range being the best categorization. Only two pieces exceeded  4 in the upper register and the lowest tones ranged from C 4 to G 3. Thus female vocal lines were relatively low.

4 in the upper register and the lowest tones ranged from C 4 to G 3. Thus female vocal lines were relatively low.

Figure 1. Garretson's voice classification ranges.

Another predominant characteristic was the presence of a major modality. Of the twenty tunes, fifteen consistently used a tonic with the major third at important cadences (indicated with an uppercase letter). This predilection may be changing, however, as four of the five tunes featuring the lowered (minor) third (indicated with lowercase letters) occurred in the last seven years of the period studied. No particular tonal center seemed to dominate as ten of the twelve possible tonal centers were used— /

/ and

and  /

/ were the only tones not used as a tonic. F, G, and A were tonics in three songs each. Composers of the selected tunes seemed to be reluctant to depart from an established tonal center: only six of the twenty songs modulated, and of these six all but one returned to the original tonal center after a brief excursion. Three of the modulations were up a second (d to e, D to E, and A to B), two were up a third (B to D), and one was up a fourth (G to C).

were the only tones not used as a tonic. F, G, and A were tonics in three songs each. Composers of the selected tunes seemed to be reluctant to depart from an established tonal center: only six of the twenty songs modulated, and of these six all but one returned to the original tonal center after a brief excursion. Three of the modulations were up a second (d to e, D to E, and A to B), two were up a third (B to D), and one was up a fourth (G to C).

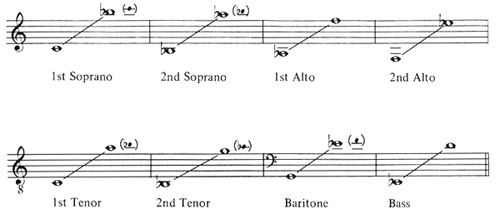

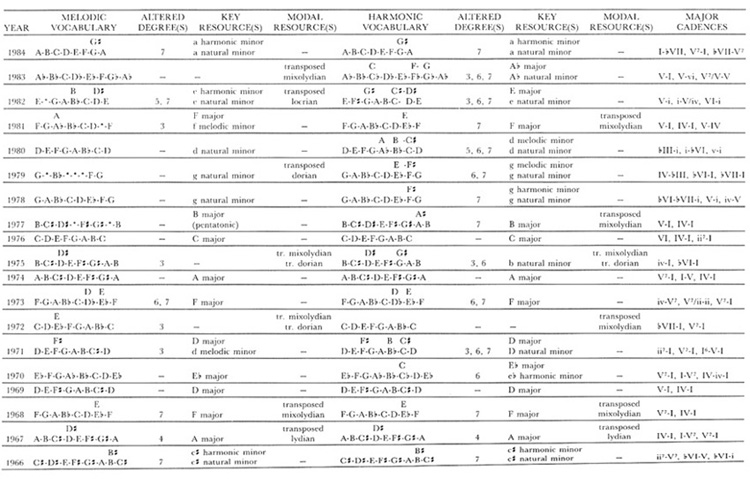

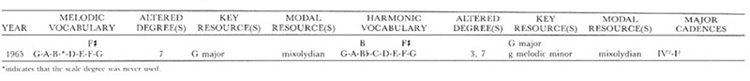

Results of the investigation for modal influences can be seen in Table 2. All tones found in each song were listed for both melody and harmony, except for non-scale or non-key tones that were obviously either upper or lower neighbors, passing tones, or alterations used to create secondary dominant chords. Root movement at strong cadence points was also considered. In the cadence column a term such as  refers to the use of the lowered sixth scale degree as the basis for a major chord. From the given tones, the most obvious implied keys (major and/or minor) and modes have been listed.

refers to the use of the lowered sixth scale degree as the basis for a major chord. From the given tones, the most obvious implied keys (major and/or minor) and modes have been listed.

Table 2. Modal Influences

Several points can be made from an examination of Table 2. First, modal influences are present in the pieces examined in this study. The lowered fifth, characteristic of the locrian mode beginning on b, can be seen in the melody of the song from 1982 and in the harmony of the song from 1980 while the raised fourth, found in the lydian mode, is present in the melody and harmony of the 1967 song. The major chords built on the first and second scale degrees of the lydian mode are an important part of the compositional structure of the 1967 song, creating a vacillating effect between scale degrees 1 and 2 as the tonal center. Strong implications of the mixolydian mode with its characteristic whole tone between degrees 7 and 8 are found in Roberta Flack's recording of The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face. The mixolydian feeling is furthered by the  -I cadential movement. The lowered seventh can be observed in Table 2 as a common phenomenon in these melodies, as all but eight of the songs at some point employ it. Of the eight not using the lowered seventh in the melody, two avoided the use of a seventh altogether.

-I cadential movement. The lowered seventh can be observed in Table 2 as a common phenomenon in these melodies, as all but eight of the songs at some point employ it. Of the eight not using the lowered seventh in the melody, two avoided the use of a seventh altogether.

One must not be too quick, however, in applying the categorization of mixolydian mode to any song with a lowered seventh, as other examples in the table show. Specifically in songs from 1968 and 1978 the lowered or flatted seventh is present but the piece is not modal. First, cadential movement typical of the major/minor system (e.g., IV-I, V7-I, and V-i) is prominent. The modal feeling is also weakened by the presence of  . In the 1978 piece the chords

. In the 1978 piece the chords  -G-

-G- , F-A-C, and G-B-D often occur consecutively. Obviously, the

, F-A-C, and G-B-D often occur consecutively. Obviously, the  chord is not indicative of the mixolydian mode. (The only mode that would have a major chord on degrees 6 and 7 would be the aeolian mode and it contains a minor i chord.) The best theoretical explanation for a

chord is not indicative of the mixolydian mode. (The only mode that would have a major chord on degrees 6 and 7 would be the aeolian mode and it contains a minor i chord.) The best theoretical explanation for a  -

- - I progression is a combination of tones from the natural minor and major vocabulary. The tones that are altered when moving from major to minor (degrees 3, 6, and 7) are the ones that typically were found to fluctuate in the pieces examined in this study, thus indicating a major/minor rather than modal basis for most of the songs.

- I progression is a combination of tones from the natural minor and major vocabulary. The tones that are altered when moving from major to minor (degrees 3, 6, and 7) are the ones that typically were found to fluctuate in the pieces examined in this study, thus indicating a major/minor rather than modal basis for most of the songs.

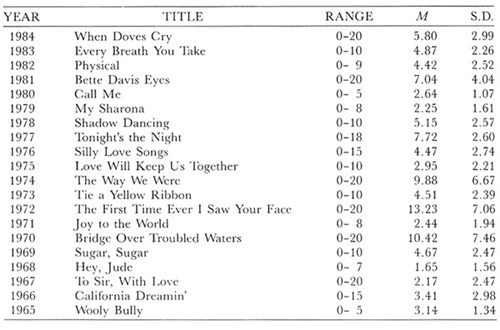

Table 3 indicates three factors pertaining to the volume or dynamics of the pieces. As explained earlier, the possible range for a piece varied from -20 (a near absence of sound) to 0 (adjusted "to accommodate the loudest point). Pieces that ranged from 0 to -5, for example Call Me (1980), never approached the soft end of the dynamic continuum. Those with a bottom limit of -20 were dynamically very soft at least once during the piece. The mean was an average of the intensity readings recorded every five seconds and is also helpful in determining the dynamic activity.

Table 3. Dynamic Activity

In comparing the pieces from 1984 and 1970 it can be seen that they both contained a range of -20 to 0 but the means of 5.80 and 10.42 indicated that the 1984 piece was closer to its loudest level more often than the 1970 piece. This is also reflected by the standard-deviation scores which indicated a clustering for the 1984 song but a wider diversity for 1970. The most limited dynamic activity occurred in the 1980 tune, while the greatest dynamic contrast was displayed in songs from 1970 and 1972.

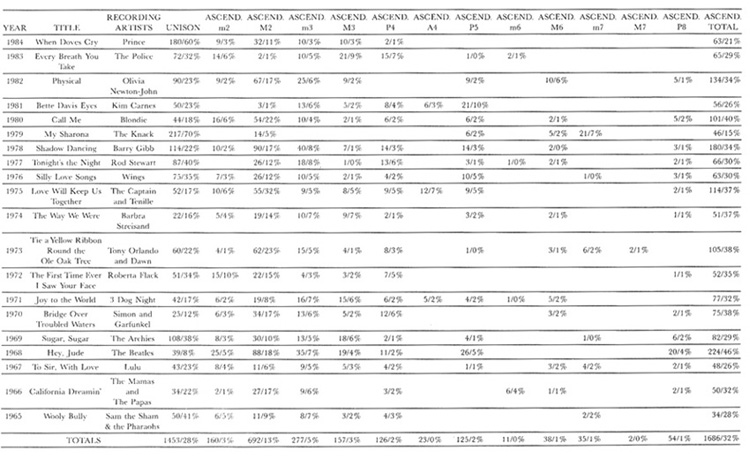

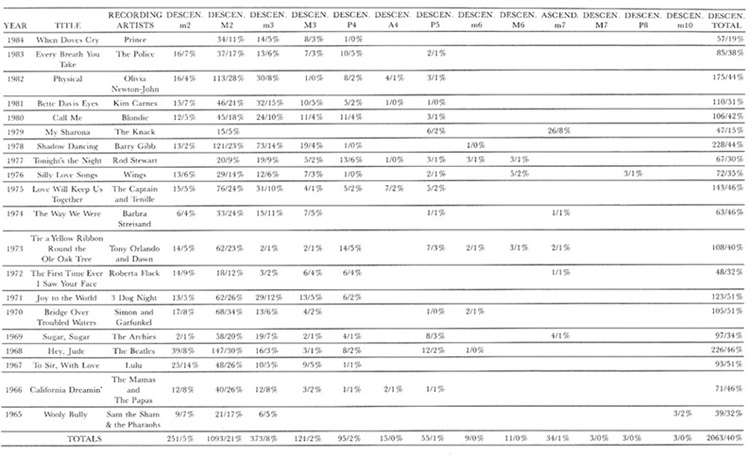

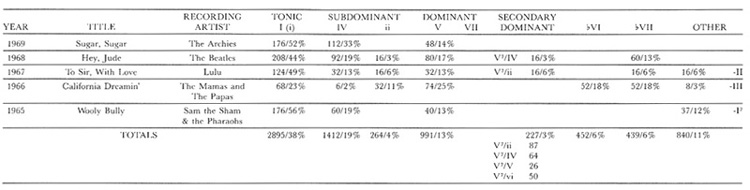

Data pertaining to melody can be seen in Tables 4 and 5. In these tables the figure on the left side of each cell represents the number of times the interval occurred in the piece while the number on the right represents the percentage of the total. For example, in the melody from 1984, the unison occurred 180 times, and sixty percent of the melodic intervals in this song were unisons.

Table 4. Melodic Motion (Ascending)

Table 5. Melodic Motion (Descending)

In the twenty pieces that were analyzed, the unison was used extensively—28% of the time. Songs from 1979 and 1984 in particular emphasized the melodic unison. Seventy percent of the melodic intervals in My Sharona were unisons, as were sixty percent of the intervals in When Doves Cry. The descending major second was used 21% of the time and the ascending second 13%. Certain intervals such as the tritone, sixth (both major and minor), seventh (both major and minor), and octave practically were never used, either in ascent or descent. Descending motion was utilized more frequently than ascending motion in fifteen of the twenty songs. In three songs there was an equal amount of ascending and descending motion.

In Table 6, it can be seen that most melodic motion (69%) is conjunct, with only 31% of the intervals being a minor third or larger (conjunct motion being defined as motion by unisons, minor seconds, and major seconds). The degree of conjunct motion ranged from 53% (1981) to 85% (1984). Thus most melodic activity in this sample of popular music is either repetition or stepwise movement.

Table 6. Melodic Motion and Direction Changes

Also listed in Table 6 are the direction changes in the melodies of the selected pieces. Direction change was investigated to see if these melodies move in long ascending and descending arches or in more jagged, back and forth (seesaw) motions. The direction change figures represent an average of how many notes occur before the melody changes direction. For example, the 1984 song reflects a direction change score of 1.62 notes. This means that on the average this melody ascended for approximately two notes and then descended for another two notes before once again ascending. Extended lines in one direction, such as an ascending scale passage, seldom appeared in these pieces. However, seesaw motion was very typical.

Chromatic alterations in the melody line occurred rarely, usually coinciding with a secondary dominant in the accompaniment.

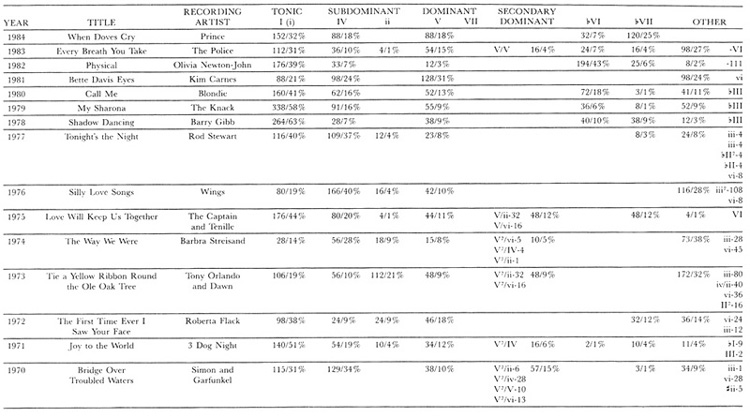

Table 7 contains information regarding harmonic activity. As in Tables 5 and 6 the left number in each cell represents a raw score and the right number a percentage of the total. In this case the left number represents a total number of beats. For example, the Tonic column for 1984 shows that 152 beats in that song exhibited a tonic harmonization, and that these were 32% of the total number of beats in the entire song including introductions, repeated endings, and codas.

Table 7. Harmonic Activity

From Table 7 it can be seen that the tonic was used extensively (38% of the time). Another interesting phenomenon that can be observed is the preference for IV (subdominant harmony) over V (dominant harmony). Overall, subdominant harmony appears approximately 50% more than dominant harmony and is more widely used in fifteen of the twenty songs. It also can be seen in Table 7 that vii° is never used, but that  and

and  appear with more frequency: these two chords together comprise 12% of the harmonic vocabulary. The

appear with more frequency: these two chords together comprise 12% of the harmonic vocabulary. The  was frequently used in

was frequently used in  -I progressions, which were common at cadence points (particularly in the songs from 1972 and 1984). In the category labeled "Other" the chords used most often were iii and vi, with each harmony accounting for 5% of the total harmonic vocabulary used in the selections. Practically no 7th, 9th, 11th, or 13th chords were used.

-I progressions, which were common at cadence points (particularly in the songs from 1972 and 1984). In the category labeled "Other" the chords used most often were iii and vi, with each harmony accounting for 5% of the total harmonic vocabulary used in the selections. Practically no 7th, 9th, 11th, or 13th chords were used.

Another facet of harmony that was investigated dealt with harmonic rhythm. Most of the pieces (twelve out of twenty) featured one chord per measure. Three of the pieces (1974, 1970, and 1966) changed at a quicker pace, typically exhibiting two chords per measure. The remaining five pieces (1983, 1982, 1979, 1975, and 1973) were built on a slower rhythmic base, usually remaining on a chord for two to four measures at a time.

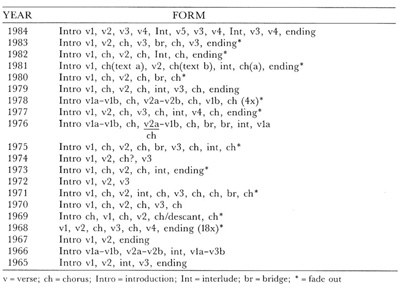

Table 8 lists the form of the twenty pieces. In this table v stands for verse. Verse was defined as a section in which the melodic line was repeated at one or several points in the song accompanied by the same harmony, each repetition with a different text. Thus v1 and v2 have the same melody but different words. The Ch in Table 8 stands for chorus. A chorus was always different harmonically and melodically from the verse and contained a set of words that remained the same each time this section was presented. Most of the songs contained only these two types of vocalized sections. However, a few included a third kind of section which was preceded and followed by the familiar verses and choruses but in itself was divergent. This type of section often featured modulations and/or new rhythmic and melodic ideas. It is called a bridge (represented with br in the table). "Intro" represents introduction and Int represents interlude. An interlude always featured an instrumental solo section that often contained an improvised solo line by the guitar over a previously established harmonic framework.

Table 8. Formal Structure

The only problem with the previous set of definitions occurred when a chorus was used several times with one text and then repeated with a different text (1981), or when a particular section of a verse was repeated (1978). These were noted in Table 8 by the use of Chorus (text a or text b) and v1a-v1b and v2a-v1b.

Based on Table 8 a typical form among the twenty pieces consisted of Intro, v1 (or v1, v2) chorus, v2 (or v3), chorus, bridge or instrumental interlude, optional verse, chorus, and instrumental ending. An introduction occurred in all but one of the pieces (1968) and was restricted to instruments in all but one (1974). Verses were 8 to 20 measures in length with 8-measure verses being the most popular (nine songs had 8-measure verses). Most verses were subdivided into symmetrical phrases, but asymmetrical phrase structure was found in tunes from 1981 (6 - 8), and 1967 (12 - 8). Phrase extension also created asymmetry in tunes from 1977 (4 + 4 + 2), 1973 (8 + 8 + 4), and 1971 (4 + 4 + 2).

The bridge sections, as previously mentioned, were the areas which consistently reflected the greatest compositional creativity. They often featured modulations (1983, 1975, 1971) and/or new accompaniment (rhythmic) devices (1976). If a bridge was not used, an instrumental interlude was almost always employed to create contrast. Endings typically consisted of short bits of text being enunciated over the established verse or chorus harmonies. This continued throughout the fade until silence was achieved. Over half the pieces ended in this manner. In two pieces (1968 and 1978) the fade-out ending is an essential part of the song. In Hey Jude the final 4 measures are repeated 18 times during the fade process.

Several exceptions to the established common form were employed. The 1984 song contains no chorus but instead focuses on multiple verses and contains two interludes. The 1972 song also does not contain a chorus, but rather three verses. The 1969 song begins with the chorus and positions the verses within the center of the piece. It also employs a vocal descant section over the established harmony, rather than using an instrumental interlude. Perhaps the most original deviation was used by composer Paul McCartney (1976), who designed the verse so that it could be superimposed upon the chorus. These two sections then were combined in a later section. The texts of these pieces dealt with a limited number of subjects. The most common theme (occurring in eight of the twenty songs) involved the pleas for love from another or an invitation or suggestion to make love ("please love me" or "please make love to me"). The second most common topic was an expression of love—"I love you." Other topics included nostalgia, brotherhood, the joys of life, and dancing. The range of quality and seriousness among the twenty texts perhaps may be reflected best by listing two examples:

(from Joy to the World, 1971)

Jeremiah was a bullfrog,

Was a good friend of mine.

I never understood a single word he said,

But I helped him a-drink-in his wine.(from The Way We Were, 1974)

Can it be that life was all so simple then,

Or has time rewritten every line?

If we had the chance to do it all again,

Tell me would we? . . . Could we?

Another element relating to text is its setting. Syllabic text setting was almost always the rule. While melismas of two or three notes occurred in a few songs and one even lasted for six notes (1972), this type of text setting is very rare. In general every note was given an accompanying syllable in the text.

DISCUSSION

Certain results from Table 1 are worthy of attention. Why were the majority of tunes approximately three to four minutes in length? An initial suspicion was that the capacitiy of a 45-rpm record dictated such brevity. However, the longest tune on a record of this format (Hey Jude) was over seven minutes in length and thus seemed to negate this explanation.

A series of contacts with radio and record company managers revealed that Contemporary Hit Record (CHR) stations dictate the three- to four-minute format to musicians and record companies. The radio station managers who were consulted said that because an average listener tunes in for a relatively brief time (approximately fifteen to twenty minutes) he or she will not continue to listen to a very long song (especially if it is one that the listener dislikes). Songs in the three- to four-minute range are thought to give a radio station flexibility in changing the texture, tempo, and vocal sound of pieces frequently, thus attracting and/or sustaining a wider range of listeners. One record company executive said that the three- to four-minute length has become so widely accepted that songs exceeding this length are often released in an edited version targeted specifically at CHR stations so as to achieve widespread air time and consequently mass appeal.

The dominance of duple meter in the twenty selected pieces analyzed in this study is clear. Whether this is a result of composer preference or consumer demand is unclear.

In Tables 4 and 5, certain qualities are also worthy of discussion. The frequent use of melodic unisons seems to imply that melody may be merely a vehicle for text delivery. In the 1976 song, for example, the first thirteen tones and eighteen of the first twenty are the same pitch. Certainly the emphasis is not on creating a captivating motif! Also, Ortmann's suggestion regarding the "fundamentally ascending basis of our tonal system"13 was not substantiated by this study. Descending melodic motion was much more prevalent in these pieces.

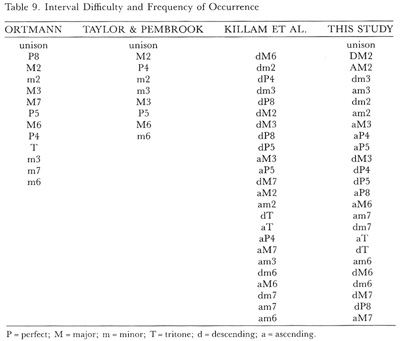

Another result that may be intriguing to music researchers deals with the percentage of intervals used in these tunes. The results of three studies that have attempted to determine the degree of difficulty associated with various intervals are listed in the first three columns of Table 9.14 The most easily identified intervals are at the top and the most difficult ones are at the bottom. The fourth column shows the frequency of interval occurrence in this study, with the most frequently occurring intervals at the top and the least frequently occurring intervals at the bottom. In the first three lists it can be seen that, in general, as intervals get larger they also become more difficult to identify. From this study it can be seen that larger intervals are used less frequently. The list for this study is very similar to Killam, Lorton, and Schubert's order, particularly in the bottom ten positions, which include seven intervals common to both lists. It may be that large intervals are missed not because they are inherently more difficult but simply because the students are not used to the sounds of these intervals.

Table 9. Interval Difficulty and Frequency of Occurrence

While some may assume that all popular music is harmonically simplistic and based on a I-IV-V framework, this research indicated otherwise. Although some songs were very simple harmonically (1965 and 1969), others used a wide selection of chords (1973 and 1970). Perhaps the most interesting aspect that emerged was a separate harmonic vocabulary and system of functional harmony in pop music. Movement from one major chord to another built on an adjacent tone was frequent. While this has occurred for centuries in classical harmony between IV and V, modern popular music has seen this type of motion expanded to I-II,  -

- , and

, and  -I. Through the continued use of such parallel movement (typically executed on the guitar by means of a series of barré chords), consecutive major chords have come to represent a logical and accepted progression.

-I. Through the continued use of such parallel movement (typically executed on the guitar by means of a series of barré chords), consecutive major chords have come to represent a logical and accepted progression.

Most of MacCluskey's generalizations on popular music were substantiated by this study. As previously mentioned, eighteen of the twenty songs featured even, simple subdivisions of the beat. These even impulses may contribute to giving popular music its "beat." MacCluskey also discussed the use of the lowered third and the avoidance of the leading tone. Although the absence of the leading tone and the presence of the lowered third can be observed in tunes from 1971, 1972, and 1975, uses of the major third and leading tone can be seen in songs from 1973 and 1983. Therefore, on the basis of the twenty songs examined in this study, MacCluskey's statement should be modified to say that thirds are sometimes lowered to contrast with the normal (raised) third. The seventh is usually lowered when accompanied by a  harmonization but the leading tone often is present during traditional V7-I cadences.

harmonization but the leading tone often is present during traditional V7-I cadences.

MacCluskey's references to the harmonic nature of popular music were very accurate. Popular music does seem to be oriented toward the subdominant. The subdominant was particularly prominent in songs from 1977 and 1976, in which it constituted 41% and 44% of the harmonies respectively. Why this particular tone is favored is difficult to explain. Perhaps it reflects a blues heritage.

The  -I cadence is very popular, as MacCluskey suggested. However, the importance of the major II chord, as discussed by MacCluskey, was not substantiated in this study. Only one song (1967) used the II chord extensively. MacCluskey's observation regarding the avoidance of 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths was also very accurate. In pop music it seems that "color" is added by inversion or by placing a non-chord tone in the bass rather than incorporating the tone as part of the chord in the upper voices.

-I cadence is very popular, as MacCluskey suggested. However, the importance of the major II chord, as discussed by MacCluskey, was not substantiated in this study. Only one song (1967) used the II chord extensively. MacCluskey's observation regarding the avoidance of 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths was also very accurate. In pop music it seems that "color" is added by inversion or by placing a non-chord tone in the bass rather than incorporating the tone as part of the chord in the upper voices.

In many ways popular music has changed little since 1969. However, two areas that did seem to change over the twenty-year span examined in this study included the complexity of synthesized sounds and the candor of the lyrics. As technology and hardware have progressed since 1965, musical artists have incorporated these devices into their music. Perhaps the best example of this change can be heard by comparing the pieces from 1965 and 1984. Synthesized sounds instantly delineate between "modern" and "old-fashioned."

The change in lyrical expressionism can be observed by comparing the lyrics of songs from 1969 and 1982. In the 1969 song Sugar, Sugar, the lyricist stated his desires by saying, "Sugar, honey, you are my candy girl and you've got me wanting you." By 1982 this same sentiment was being conveyed with, "You've gotta know that you're bringin' out the animal in me. Let's get physical. Let's get animal. Let me hear your body talk."

This study was conducted in order to establish the compositional and performance techniques associated with selected pieces of popular music. Subsequent studies are needed to compare these pieces with other genres (e.g., classical art songs, American folk songs, and perhaps even obscure pop selections) in an attempt to discover both common and contrasting elements of each. Perhaps as a result of continued research popular music will attain an air of legitimacy and be incorporated into the mainstream of music education.

1Allen P. Britton, Arnold Broido, and Charles L. Gary, "The Tanglewood Declaration," in Documentary Report of the Tanglewood Symposium, ed. Robert A. Choate (Washington: Music Educators National Conference, 1968), 139.

2William H. Cornog, "For Most Children, Music Outside the Schools Is the Only 'Real' Music," in Tanglewood Symposium, 3; Karl D. Ernst et al., "Implications for the Music Curriculum," in Tanglewood Symposium, 136.

3R. Douglas Greer, Laura G. Dorow, and Andrew Randall, "Music Listening Preferences of Elementary School Children," Journal of Research in Music Education 22 (1974): 284-91; C.H. Benner, "Teaching Performing Groups," in Research to the Music Classroom No. 2, (Washington: Music Educators National Conference, 1972).

4Michael L. Mark, Contemporary Music Education (New York: Schirmer Books, 1978), 108.

5Graham Vulliamy and Edward Lee, Popular Music: A Teacher's Guide (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982); R. Fred Kern, "Using Informal Music in Teaching," Clavier, November 1977:32-35; Lee Evans, "Popular Music in Music Education," The Piano Quarterly 122 (1983):54-55; P. Farmer, "Pop Music in the Secondary School: A Justification," Music in Education 40 (1976):217-19.

6Thomas MacCluskey, "Rock in Its Elements," Music Educators Journal, November 1969:49-51.

7Vulliamy and Lee, Popular Music: A Teacher's Guide; Richard Middleton and David Horn, Popular Music: Theory and Method (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982); Randall G. Pembrook, "Popular Music in Research and in the Classroom," Update 5 (1986):6-10; P.A. Russell, "Experimental Aesthetics of Popular Music Recordings: Pleasingness, Familiarity, and Chart Performance," Psychology of Music 14 (1986):33-43.

8Charles Hamm, "Some Thoughts on the Measurement of Popularity in Music," in Popular Music Perspectives, ed. David Horn and Philip Tagg (Göteborg: Wheaton, 1982), 3.

9J. David Boyle, Glenn L. Hosterman, and D.S. Ramsey, "Factors Influencing Pop Music Preferences of Young People," Journal of Research in Music Education 29 (1981):47-55.

10Hamm, "Measurement of Popularity," 3.

11Jan LaRue, Guidelines for Style Analysis (New York: Norton, 1970), 4-5.

12Robert L. Garretson, Conducting Choral Music (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1981).

13Otto O. Ortmann, "Some Tonal Determinants of Melodic Memory," The Journal of Educational Psychology 24 (1933):454-67.

14Rosemary N. Killam, Paul V. Lorton, Jr., and Earl D. Schubert, "Interval Recognition: Identification of Harmonic and Melodic Intervals," Journal of Music Theory 19 (1975):212-33; Otto O. Ortmann, Problems in the Elements of Ear Dictation (Baltimore: Peabody Conservatory of Music, 1934); Jack A. Taylor and Randall G. Pembrook, "Strategies in Memory for Short Melodies: An Extension of Otto Ortmann's 1933 Study," Psychomusicology 3 (1984):16-35.